Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental and physical health of the world population. This study aims to investigate incidence of sleep-related difficulties and post-traumatic stress disorder in the school-aged children after 1 year of the pandemic.

Methods

A sample of Italian children (6-12 years) was queried about their sleep behaviors after 1 year of the pandemic, answering the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ). We also evaluated trauma symptoms with the Children's Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8).

Results

Among 205 participants, 184 (89.8%) presented sleep-related difficulties. Out of all, 99 (48.3%) had a high risk to develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Ninety-five (51.6%) children with sleep-related difficulties also presented an abnormal CRIES-8 total score. A correlation was found between the CSHQ total score and the CRIES-8 total score (r = 0.354, P < .01).

Conclusions

The sleep-related difficulties occurring during COVID-19 outbreak may compound to increase the risk to develop post-traumatic stress disorder among Italian children.

Keywords: children, COVID-19 outbreak, CSHQ, CRIES-8, sleep disorders

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically affected the mental and physical health of the population all over the world. It is known that COVID-19 causes more health risks for adult patients than children, who have less severe symptoms or an asymptomatic course when infected with SARS-CoV-2.1 Nevertheless, their health-related quality of life has been severely impacted by this pandemic.2‐4 Quarantine measures, social distancing, fear of contagion, estrangement from family and friends, bereavements, and negative economic consequences have negatively changed children and adolescents. In addition, despite the restart of commercial activity after the lockdown periods, schools continued to be closed in many countries, giving rise to further alienation of students.

The pandemic altered first the routine of a very large number of people, but sleep quality and circadian rhythm also were influenced by these changes.

Sleep is a vital process aimed at maintaining the homeostasis of the human organism and improving the quality of life. Sleep quality is closely connected to psychophysical well-being and mental health.5,6 Some studies conducted in Italy at the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown showed an alarming increase of sleep disturbances in adults, but also a worsening of sleep quality in children.7,8

Previous studies have documented an association between poor maternal and infant sleep quality that appears to be related to high levels of maternal anxiety. An Iranian study showed that mothers reported mild to high levels of COVID-19 anxiety in 80% of cases and a negative change in child's sleep quality in about 30% of cases.9 A survey conducted during COVID-19 outbreak on a large number of children showed a greater delay in sleep-wake schedule as well as an increase of sleep disorders.10

However, although several authors have highlighted the increase in sleep disturbances in the pediatric population during the pandemic, currently there are no studies showing a correlation between posttraumatic stress disorder caused by COVID-19 outbreak and sleep disturbances in children.

Our study therefore aims to investigate the incidence of sleep-related difficulties in the Italian pediatric population in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic and analyze the traits of post-traumatic stress disorder manifested by some of them. The secondary objective was to identify a possible correlation between sleep-related difficulties and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Material and Methods

Study Participants

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted in a Tertiary University Hospital of Rome (Italy) from March to June 2021, 1 year after social isolation due to COVID-19 outbreak.

All subjects were invited to participate by answering, independently or with the help of a parent, to an anonymous questionnaire available on the Google Forms platform (Google Inc). The link to the online survey was spread to all participants via WhatsApp. Participants completed an anonymous online survey, after reading the informed consent form and explicitly accepting participation in the survey.

We included healthy children, aged between 6 and 12 years, attending primary and secondary schools throughout Italy (mainly from Central and Southern part of the Country). Some of these children were recruited to our hospital during routine primary care visits at our pediatric outpatient clinic. To eliminate the bias related to the psychological stress of the children admitted to the hospital, we decided to involve some primary and secondary schools in Italy.

The exclusion criteria of the study were as follows: not being in the age range of 6-12 years; having genetic diseases or neurologic and psychiatric diseases (such as psychomotor retardation, learning disorders, epilepsy, autism, anxiety, preexisting sleep disorders, or posttraumatic stress disorder); more than 20% of answers were invalid or missing.

Questionnaires

The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: (1) sociodemographic characteristics; (2) sleep quality assessment with the Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), and (3) trauma symptoms evaluation during the COVID-19 outbreak with the Children's Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8).

Sociodemographic information included age, gender, geographical area (northern, central, or southern Italy), school attending, and parental separation/divorce. In addition, children and adolescents were asked if they owned a smartphone or tablet and if their families used streaming television (such as Netflix, Sky, etc). Finally, we also asked if the use of smartphone or tablets before going to sleep had increased or not, compared to before the pandemic. The possible answers were “as before,” “more than before,” and “less than before.”

Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ), developed by Owens et al and validated by Fiş and colleagues,11,12 was used to evaluate sleep quality and the occurrence of sleep-related difficulties in the study group. It consists of 33 items that examine sleep behavior in children, divided into 8 subgroups: (1) bedtime resistance, (2) sleep onset delay, (3) sleep duration, (4) sleep anxiety, (5) night wakings, (6) parasomnias, (7) sleep disordered breathing, and (8) daytime sleepiness. The frequency of sleep-related difficulties is evaluated on a 3-point scale: usually (5 to 7 times per week, 3 points), sometimes (2 to 4 times per week, 2 points) or rarely (0 to 1 time per week, 1 point). Items 1, 2, 9, 10, and 26 are reverse coded. A total score ≥41 points is considered as a “clinically significant level” of sleep-related difficulties.

The Children's Impact of Event Scale (CRIES-8) is a screening test ideated by Perrin et al13 and subsequently validated and revised by Sahin et al14 and by Iz et al15 to identify children at risk to develop post-traumatic stress disorders. It included 8 items investigating about posttraumatic stress symptoms in children, and in our study, its questions were adapted to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

A total score ≥17 gives high probability that the child would obtain a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. In addition, 2 scores were also calculated for the Intrusion and Avoidance subscales.

Statistical Analysis

First, normality of distribution of continuous variables was tested by means of Shapiro-Wilk test. Results are expressed as count and percentages for categorical variables and as mean and standard deviation for the continuous variables. Statistical comparisons were obtained by χ2 tests or Fisher exact test, as appropriate, for categorical variables. Differences among 2 groups in continuous variables were tested by 2-tailed unpaired Student t test. One-way analysis of variance was used for multiple comparisons, and a Bonferroni correction was applied to the item analyses. The Pearson correlation test was performed to evaluate the association between CHSQ and CRIES-8 scores. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Finally, a multiple linear regression model was created to test independent predictors of the change in sleep quality, evaluated through the variation in CSHQ total score. All data were analyzed with SPSS for Windows, version 25.0.

Results

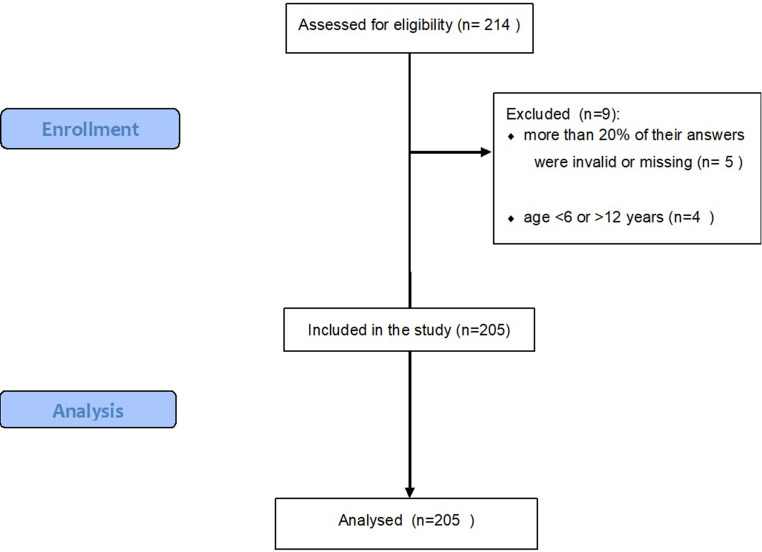

Two hundred fourteen questionnaires were returned and 5 were excluded because more than 20% of their answers were invalid or missing. From 209 valid questionnaires, 4 (2%) were excluded because of age <6 or >12 years. Therefore, 205 questionnaires were included in our analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study design.

The participant's mean age was 9.9 ± 1.9 years, and 114 (56%) were female. All the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants Characteristics (N = 205).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 91 (44.4) |

| Female | 114 (55.6) |

| Age, y | |

| 6-7 | 28 (13.7) |

| 8-9 | 55 (26.9) |

| 10-11 | 61(29.7) |

| 12 | 61 (29.7) |

| Attended school | |

| Primary school | 128 (62.4) |

| Secondary school | 77 (37.6) |

| Geographic area | |

| Southern Italy | 68 (33.2) |

| Central Italy | 132 (64.4) |

| Northern Italy | 5 (2.4) |

| Parents’ assistance in answering the questionnaire | |

| Yes | 141 (68.8) |

| No | 64 (31.2) |

| Family situation | |

| Married parents | 184 (89.8) |

| Separated parents | 21 (10.2) |

| Possession of smartphone/tablet | |

| Yes | 153 (74.6) |

| No | 52 (25.4) |

| Family use of streaming TV | |

| Yes | 162 (79.0) |

| No | 43 (21.0) |

| Use of smartphone before sleeping | |

| More than before the pandemic | 110 (53.7) |

| As before the pandemic | 79 (38.5) |

| Less than before the pandemic | 16 (7.8) |

In the survey, 153 (75%) students declared owning a smartphone or a tablet and 162 (79%) using streaming television (TV). One hundred ten (54%) participants stated that they use their smartphone/tablet now before going to sleep more than before the pandemic.

The CSHQ total score mean was 51.6 ± 9.3, whereas the mean scores in 8 subgroups were 9.46 ± 2.92 for bedtime resistance, 1.9 ± 0.8 for sleep onset delay, 4.6 ± 1.6 for sleep duration, 3.3 ± 1.3 for sleep anxiety, 4.2 ± 1.6 for night wakings, 9.7 ± 2.6 for parasomnias, 3.5 ± 1.0 for sleep-disordered breathing, and 14.9 ± 2.9 for daytime sleepiness. In summary, 184 participants (90%) presented a CSHQ score ≥41, consistent with sleep-related difficulties.

Regarding the CSHQ mean total score, no statistically significant differences emerged for gender, geographical area, questionnaire respondents (child or parents), school attended, married or divorced parents, possession of a smartphone or tablet, and use of streaming TV. Analyzing in more detail the various subgroups within the questionnaire, we observed a higher score for bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, and night wakings in the group of children attending primary school (P < .001, P = .012, and P = .005, respectively) but a higher score for sleep duration in the group of secondary school (P < .001). The children of divorced parents had a higher bedtime resistance score than the children of married parents (10.8 ± 3.5 vs 9.3 ± 2.8, P < .031). In addition, the children who owned a smartphone/tablet presented a daytime sleepiness score higher than those who did not (15.1 vs 14.1, P < .34), whereas no difference emerged for children who used streaming TV. Regarding the use of smartphone or tablet before going to sleep compared with before the pandemic, our analysis showed significant differences in the CSHQ total score mean: the children who declared using more smartphone/tablet presented a higher CSHQ total score (53.6 ± 9.0) than those who stated using them less (47.9 ± 6.7, P < .001).

For the second objective of the study, we analyzed also all the answers of the CRIES-8 in the same population. The mean total score was 15.8 ± 9.9, with a mean Intrusion score of 7.6 ± 5.0 and a mean Avoidance score of 8.2 ± 6.1. One hundred six (52%) children had a normal CRIES-8 score, whereas 99 (48%) showed a CRIES-8 score ≥17 resulting in a high probability to obtain a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. There were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls or between questionnaire respondents (child or parents). However, we observed a higher avoidance score for the children attending primary school compared with those attending secondary school (8.8 ± 6.4 vs 7.1 ± 5.5, P < .05). No statistically significant differences emerged for parental separation, possession of a smartphone or tablet, and use of streaming TV. Instead, a statistically significant difference emerged between the mean CRIES-8 total score and the use of electronic devices before going to sleep compared with the prepandemic period: the children who reported using more smartphone/tablet presented a higher score (18.1 ± 10.0) than those who stated using them less (14.5 ± 11.6) (P = .001).

Finally, we studied the existing relationship between sleep-related difficulties and posttraumatic stress disorder. Among the 99 children with pathologic CRIES-8 total score, 95 (96%) had sleep-related difficulties and only 4 (4%) did not; χ2(1, 205) = 8.0, P = .005. We identified a weak to moderate positive correlation between the CSHQ total score and the CRIES-8 total score (r = 0.354, P < .001). Therefore, we estimated a multiple linear regression model to determine how much variability in total CSHQ score could be jointly explained by age, sex, school attended, parental separation, possession of a smartphone or tablet, use of streaming TV, use of smartphone or tablet before bedtime compared to before the pandemic, and CRIES-8 total score. The analysis showed no correlation with sex, school attended, parental separation, possession of a smartphone or tablet, and use of streaming TV; instead, lower age was associated with an increased likelihood of having a higher CSHQ total score (β = −0.224, P < .032). In addition, the standardized beta coefficients showed that 2 other variables contributed most to having a high CSHQ total score: telephone use before sleeping (β = 0.276, P < .000) but especially the CRIES-8 total score (β = 0.307, P < .000) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Linear Regression Analysis of the Independent Predictors of the Change in Sleep Quality, Evaluated Through the CSHQ Total Score.

| Dependent variable | ||

|---|---|---|

| CSHQ total score | ||

| Independent variables | β (95% CI) | P value |

| Gender | −0.017 (−2.70, 2.07) | .794 |

| Age | −0.224 (−1.96, −0.09) | <.05 |

| Attended school | 0.134 (−1.35, 6.50) | .197 |

| Parental separation | 0.091 (−1.14, 6.74) | .163 |

| Possession of smartphone / tablet | 0.058 (−1.98, 4.45) | .450 |

| Family use of TV subscriptions | −0.045 (−3.98, 1.94) | .498 |

| Telephone use before sleeping | 0.276 (2.25, 6.20) | <.01 |

| CRIES-8 total score | 0.307 (0.17, 0.41) | <.01 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRIES-8, Children's Impact of Event Scale; CSHQ, Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire.

Discussion

This study provides a description of sleep habits and sleep-related difficulties in a sample of children after 1 year of home confinement during the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, the psychosocial impact of the pandemic on this population was evaluated through CRIES-8 analyzing the traits of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Prevalence of Sleep-Related Difficulties

Our survey showed that the COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictive measures taken to contain the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 led to major changes in the sleep-wake rhythm of children and adolescents: we observed a high prevalence (90%) of sleep-related difficulties in our population after 1 year of lockdown.

This finding is impressive and is much higher than other previous observations carried out in the pre-COVID era. Lewien et al in a survey conducted on a large sample of patients reported a prevalence of sleep-related difficulties in 22.6% of children and 20% of adolescents in their sample.16 In literature, there are different reports about the prevalence of sleep-related difficulties in children and adolescents, ranging from 15% to 44%.17 However, it is important to highlight that rates of sleep-related difficulties vary according to age, ethnicity, cultural differences, socioeconomic status, and geographic location. In addition, we are living in a particular historical moment, in which, in order to defeat the COVID-19 pandemic, the government has had to implement restrictive social containment measures for a long time. Among these, the closure of public places and schools and distance learning have had the greatest impact on the psychological and social aspects of Italian children. A study conducted in China at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak on a large number of children showed a lower CSHQ total score and a reduced prevalence of sleep-related difficulties in the COVID-19 sample compared with the 2018 sample.18 This is in contrast to our results, but it could be linked to 2 aspects: on the one hand, the different geographical area in which the study was carried out, but above all it was the time in which it was carried out (February 2020), a period in which the effect of prolonged social isolation could not yet be observed. Instead, Bruni et al reported that the COVID-19 lockdown increased sleep disturbance in all age groups except adolescents.10

Our survey showed no gender differences in sleep-related difficulties either among children or adolescents, contrary to Lewien et al, who described a higher prevalence of sleep-related difficulties among males in children and among females in adolescents.16 However, other previous studies showed inconsistent results about gender differences regarding sleep-related difficulties in children.19,20

Analyzing the CSHQ subscales, in children attending primary school we observed more bedtime resistance, sleep anxiety, and night wakings according to previous reports in the literature.16,20‐22 Consistent with previous findings,23,24 higher sleep duration score was reported in secondary school students. The sleep duration decreases physiologically as children grow older. However, changes in the lifestyles of children and adolescents during COVID-19 outbreak, mainly due to the closure of schools and distance learning, could have led to a dysregulation of sleep-wake rhythms, with older children tending to go to bed later and sleeping fewer hours overall.

In addition, an important finding of our study concerns children with separated or divorced parents. According to a previous report,25 and in our sample as well, separated parents’ children showed more bedtime resistance than the children of married parents. Different childhood experiences have been shown to be associated with various health outcomes, including sleep disorders, in adolescents and adults.25

Finally, as regarding the use of smartphone/tablet, our survey showed that children who owned a smartphone or tablet and use it before going to sleep more than before the pandemic reported a higher daytime sleepiness score. This finding was already described by other authors before the COVID-19 pandemic: a study conducted in United Arab Emirates on residents showed that poor sleep quality was correlated with excessive smart device use.26 Also Lee et al stated that children who woke up after receiving smart device notifications had lower sleep efficiency than those who did not.27

Therefore, limiting the use of electronic devices before going to sleep could be investigated to reduce sleep-related difficulties, thus promoting better sleep quality.

Trauma Reaction in Children (CRIES-8)

In order to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on children’s mental health, we administered the CRIES-8 questionnaire, which revealed how a high proportion of the study group (48%) was at high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Different authors reported that children are more susceptible than adults to the psychological effects of traumatic events that occur in their lives.28 The COVID-19 outbreak is considerably stressful for all children and can lead to traumatic stress disorder. Comparable to our findings, Abdulah et al29 reported a high stress level and a fear of coronavirus in children confined to home during the COVID-19 outbreak. A recent study conducted in China showed a moderate or severe psychological impact in 53.8% of the participants.30 The acute or chronic exposure to a traumatic event (such as social distancing, home confinement, school closure, and distance learning) activates children's biological stress response systems31,32; stress activation subsequently causes behavioral and emotional alterations similar to symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.33

As for the CRIES-8 subscales, we observed a higher Avoidance score for children attending primary school; this finding indicates that during the pandemic younger children reacted to stress by persistently trying to avoid all stimuli associated with the trauma. Differently, another study showed a prevalence of children with intrusive experience of the trauma during the COVID-19 outbreak.29

Besides, children who reported using their smartphone or tablet before going to sleep more now than before the pandemic had higher CRIES-8 scores, probably because the children most worried about the pandemic took refuge in the use of the smartphone.

Finally, we evaluated the relationship between sleep-related difficulties and post-traumatic stress disorder in children during the COVID-19 outbreak, observing a weak to moderate positive correlation. Children with higher CRIES-8, who were more likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder, also had a higher CSHQ score and thus a higher prevalence of sleep-related difficulties. This finding suggests that sleep-related difficulties occurring during COVID-19 outbreak may compound to increase the risk to develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Previously, Çetin et al34 in their study showed an association between sleep problems and the traumatic perception of COVID-19 pandemic in a group of children with ADHD.

This study presents several limitations. First of all, the small number of subjects enrolled does not allow us to generalize our results to the whole pediatric population. Second, the sample was mainly from central and southern Italy; we did not manage to get many more answers to the questionnaires from children in northern Italy, so it was not possible to make statistical comparisons between the 3 geographical areas. Third, there are no measurements about sleep disorders from the prepandemic period in the enrolled children. Thus, it is difficult to make conclusions about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on them. In addition, the results of comparisons between CSHQ subscales need to be taken with caution; in fact, in previous validation studies,11,35,36 subscale scores of CSHQ showed a lower internal consistency, suggesting a nonadequate test reliability. Finally, the CSHQ and CRIES questionnaires are only screening techniques and cannot be used as evidence of disorders, which should only be diagnosed through clinical assessment by a neuropsychiatrist. However, the strength of the study is that to our knowledge, it is the first pediatric study to assess the relationship between sleep-related difficulties and the risk of developing a post-traumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 outbreak could have caused major changes in sleep behaviors among Italian children, with an increase in the prevalence of sleep-related difficulties. In addition, as observed in our sample, the pandemic could have increased in children the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder, which was found to be correlated with the increase in sleep-related difficulties. Further research on a larger sample is required to generalize our observations to all pediatric populations. In addition, other studies are needed to evaluate the differences in children with sleep-related disorders and risk for post-traumatic stress disorder between the time period before and after the onset of the pandemic.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: AC and IL designed the study. AG, SF, and GG circulated the questionnaires and collected data. AC performed statistical analysis. AC, SF, and VB wrote the paper. GDM, PV, and IL revised the final version of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final content.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “Agostino Gemelli,” IRCCS, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy (IRB number 0009923).

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Antonietta Curatola https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2430-9876

Antonio Gatto https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8778-9328

References

- 1.Curatola A, Chiaretti A, Ferretti Set al. et al. Cytokine response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Viruses .2021;13(9):1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizi A, Achak D, Aboudi Ket al. Health-related quality of life and behavior related lifestyle changes due to the COVID-19 home confinement: dataset from a Moroccan sample. Data Brief .2020;32:106239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riiser K, Helseth S, Haraldstad K, Torbjørnsen A, Richardsen KR. Adolescents’ health literacy, health protective measures, and health-related quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One .2020;15(8):e0238161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panda PK, Gupta J, Chowdhury SRet al. et al. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr .2021;67(1):fmaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva ESME, Ono BHVS, Souza JC. Sleep and immunity in times of COVID-19. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) .2020;66(suppl 2):143‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin MR. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu Rev Psychol .2015;66:143‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cellini N, Di Giorgio E, Mioni G, Di Riso D. Sleep and psychological difficulties in Italian school-age children during COVID-19 lockdown. J Pediatr Psychol .2021;46(2):153‐167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salfi F, Lauriola M, D’Atri Aet al. et al. Demographic, psychological, chronobiological, and work-related predictors of sleep disturbances during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy. Sci Rep .2021;11(1):11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zreik G, Asraf K, Haimov I, Tikotzky L. Maternal perceptions of sleep problems among children and mothers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Israel. J Sleep Res .2021;30(1):e13201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruni O, Malorgio E, Doria Met al. et al. Changes in sleep patterns and disturbances in children and adolescents in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak. Sleep Med .2021:S1389-9457(21)00094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep .2000;23(8):1043‐1051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiş NP, Arman A, Ay Pet al. et al. Cocuk Uyku Alışkanlıkları Anketinin Turkce gecerliliği ve guvenilirliği. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg .2010;11:151‐160. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perrin S, Meiser-Stedman R, Smith P. The Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale (CRIES): validity as a screening instrument for PTSD. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2005;33:487‐498. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahin NH, Batigün AD, Yilmaz B. Psychological symptoms of Turkish children and adolescents after the 1999 earthquake: exposure, gender, location, and time duration. J Trauma Stress .2007;20(3):335‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iz M, Ceri V, Layik ME, Ay FB. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder following unintentional injuries in children. Eastern J Med. 2019; 24(2): 182‐189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewien C, Genuneit J, Meigen C, Kiess W, Poulain T. Sleep-related difficulties in healthy children and adolescents. BMC Pediatr .2021;21(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mindell JA, Sadeh A, Kwon R, Goh DY. Cross-cultural differences in the sleep of preschool children [published correction appears in Sleep Med. 2014;15(12):1595–6]. Sleep Med. 2013;14(12):1283‐1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Z, Tang H, Jin Qet al. et al. Sleep of preschoolers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak. J Sleep Res .2021;30(1):e13142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uebergang LK, Arnup SJ, Hiscock H, Care E, Quach J. Sleep problems in the first year of elementary school: the role of sleep hygiene, gender and socioeconomic status. Sleep Health .2017;3(3):142‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schlarb A, Gulewitsch MD, Weltzer V, Ellert U, Enck P. Sleep duration and sleep problems in a representative sample of German children and adolescents. Health .2015;07(11):1397‐1408. [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Litsenburg RRL, Waumans RC, van den Berg G, Gemke RJBJ. Sleep habits and sleep disturbances in Dutch children: a population-based study. Eur J Pediatr .2010;169:1009‐1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ophoff D, Slaats MA, Boudewyns A, Glazemakers I, van Hoorenbeeck K, Verhulst SL. Sleep disorders during childhood: a practical review. Eur J Pediatr .2018;177:641‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dollman J, Ridley K, Olds TS, Lowe E. Trends in the duration of school-day sleep among 10- to 15-year-old south Australians between 1985 and 2004. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:1011‐1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olds TS, Blunden S, Petkov J, Forchino F. The relationships between sex, age, geography and time in bed in adolescents: a meta-analysis of data from 23 countries. Sleep Med Rev .2010;14:371‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman DP, Liu Y, Presley-Cantrell LR, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and frequent insufficient sleep in 5 U.S. States, 2009: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health .2013;13:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abedalqader F, Alhuarrat MA, Ibrahim G, et al. The correlation between smart device usage & sleep quality among UAE residents. Sleep Med .2019;63:18‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee PH, Tse ACY, Cheung Tet al. et al. Bedtime smart device usage and accelerometer-measured sleep outcomes in children and adolescents. Sleep Breath .2022;26(1):477-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones RT, Ribbe DP, Cunningham P. Psychosocial correlates of fire disaster among children and adolescents. J Trauma Stress .1994;7(1):117‐122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdulah DM, Abdulla BMO, Liamputtong P. Psychological response of children to home confinement during COVID-19: a qualitative arts-based research [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 12]. Int J Soc Psychiatry .2020;20764020972439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Pan R, Wan Xet al. et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health .2020;17(5):1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEwen BS. The neurobiology of stress: from serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Res .2000;886(1–2):172‐189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J Psychosom Res .2002;53(4):865‐871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charney DS, Deutch AY, Krystal JH, Southwick SM, Davis M. Psychobiologic mechanisms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry .1993;50(4):295‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Çetin FH, Uçar HN, Türkoğlu S, Kahraman EM, Kuz M, Güleç A. Chronotypes and trauma reactions in children with ADHD in home confinement of COVID-19: full mediation effect of sleep problems. Chronobiol Int .2020;37(8):1214‐1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parreira AF, Martins A, Ribeiro F, Silva FG. Clinical validation of the Portuguese version of the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ-PT) in children with sleep disorder and ADHD. Acta Med Port .2019;32(3):195‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waumans RC, Terwee CB, Van den Berg G, Knol DL, Van Litsenburg RR, Gemke RJ. Sleep and sleep disturbance in children: reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the Child Sleep Habits Questionnaire. Sleep .2010;33(6):841‐845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]