Abstract

Background:

Girls with autism spectrum condition (ASC) are chronically under-diagnosed compared to boys, which may be due to poorly understood sex differences in a variety of domains, including social interest and motivation. In this study, we use natural language processing to identify objective markers of social phenotype that are easily obtained from a brief conversation with a non-expert.

Methods:

87 school-aged children and adolescents with ASC (17 girls, 33 boys) or typical development (TD; 15 girls, 22 boys) were matched on age (Mean=11.35y), IQ estimates (Mean=107), and – for ASC participants – level of social impairment. Participants engaged in an informal 5-minute “get to know you” conversation with a non-expert conversation partner. To measure attention to social groups, we analyzed first-person plural pronoun variants (e.g., “we” and “us”) and third-person plural pronoun variants (e.g., “they” and “them”).

Results:

Consistent with prior research suggesting greater social motivation in autistic girls, autistic girls talked more about social groups than did ASC boys. Compared to TD girls, autistic girls demonstrated atypically heightened discussion of groups they were not a part of (“they”, “them”), indicating potential awareness of social exclusion. Pronoun use predicted individual differences in the social phenotypes of autistic girls.

Conclusions:

Relatively heightened but atypical social group focus is evident in autistic girls during spontaneous conversation, which contrasts with patterns observed in autistic boys and TD girls. Quantifying subtle linguistic differences in verbally fluent autistic girls is an important step toward improved identification and support for this understudied sector of the autism spectrum.

Keywords: Autism spectrum condition, language, social phenotype, sex differences, pronouns

Introduction

Autism spectrum condition (ASC) is a complex, heterogeneous neurodevelopmental challenge that affects 1 in 54 children (Maenner & et al., 2020), and is characterized by social communication difficulties and repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The majority of individuals with ASC acquire spoken language (Rose et al., 2016; Tager-Flusberg & Kasari, 2013), but nonetheless face a variety of challenges in fitting into society (Friedman, Sterling, et al., 2019; Müller et al., 2008; Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010). Girls are diagnosed less often with ASC than are boys (Baio et al., 2018) even when they have comparable symptom profiles (Dworzynski et al., 2012), which may be due to minimally understood sex differences in the way ASC manifests (Cola et al., 2020). For example, recent research suggests that autistic girls and boys present distinct symptom profiles in a variety of domains including social attention (Harrop et al., 2019, 2020), gesture (Rynkiewicz et al., 2016), imaginative play (Beggiato et al., 2017), social motivation (Sedgewick et al., 2016), and language (Boorse et al., 2019; Goddard et al., 2014; Kauschke et al., 2016; Parish-Morris et al., 2017; Sturrock et al., 2019). Failure to understand the ways in which autistic girls present similarly to (or differently from) autistic boys likely contributes to systematic under-diagnosis (Loomes et al., 2017) and critical missed opportunities to support autistic girls and women.

Given that language is a window into the human mind, closely analyzing language use in this population could shed light on how children and adolescents on the spectrum perceive the world. In particular, words produced during natural conversations might reflect individual differences in social phenotype for girls and boys with ASC. Motivation to engage socially has been argued to be a core deficit in autism (Chevallier et al., 2012), but research in this area does not always produce consistent results – perhaps due to unmeasured heterogeneity in study samples (Clements et al., 2018). One important source of heterogeneity in social motivation research may stem from autistic girls and women, who have been argued to demonstrate enhanced social motivation relative to autistic boys (Sedgewick et al., 2016). Although it is currently unknown whether differences in social motivation can be detected in natural language, examining how much children talk about other people (as indexed by personal pronouns) could provide initial insights.

Personal pronouns

Traditionally, when analyzing language, researchers have focused on semantically rich content words like nouns and verbs (Crandall et al., 2019; McDuffie et al., 2006). Function words, including pronouns, articles, prepositions, conjunctions, and auxiliary verbs, are often overlooked or discarded from lexical analyses. However, more than half of all spoken words are function words (Rochon et al., 2000), and these “throwaway” words contain meaningful individual variation that predict a variety of compelling outcomes (Chung & Pennebaker, 2007; Gorman et al., 2016; Irvine et al., 2016; Pennebaker, 2011; Pennebaker et al., 2003, 2015). Personal pronouns, in particular, typically refer to individuals or groups of people (Kitagawa & Lehrer, 1990). Variants include first person singular (“I”), first person plural (“we”), third person singular (“he/she”), third person plural (“they”), and second person (“you”) forms, and have been studied in relation to a wide variety of social and cognitive topics (Davis & Brock, 1975; Simmons, Gordon, & Chambless, 2005; Twenge, Campbell, & Gentile, 2012; Badr et al., 2016; Neysari et al., 2016; Nook, Schleider, & Somerville, 2017). For example, leadership status and power relationships are reflected in personal pronoun use, such that leaders with greater power use more first-person plural pronouns (e.g., we, us) than those with less power (Kacewicz et al., 2014). Patterns of personal pronoun use also vary according to audience characteristics. In private accounts of relationship breakups (journal entries), people use more first person singular (I, me) and third person plural (they, them) pronouns than in public accounts (blog posts) of these same breakups, where they use more first-person plural pronouns (we, us) (Blackburn et al., 2014). Together, these results suggest that personal pronouns may be sensitive indicators of interpersonal dynamics that vary according to contextual factors such as target audience.

Personal pronouns also reveal information about people’s mental states and personalities, suggesting that pronoun use might be informative for understanding individuals with psychiatric and neurodevelopmental differences (Boals & Klein, 2005; Brockmeyer et al., 2015; Watson et al., 2012; Kleim et al., 2018; Lyons, Aksayli, & Brewer, 2018). For example, college students with current or past depression use more first-person singular pronouns in written essays than students who were never depressed (Rude et al., 2004). In a study of narcissistic personality, participants spoke for 5 minutes about any topic they chose, and then completed a narcissism personality inventory. Greater narcissism was associated with the presence of more first-person plural pronouns (we, us) in participant monologues (Raskin & Shaw, 1988).

Personal pronouns in ASC

A significant body of research suggests that individuals with ASC use personal pronouns differently than matched control participants without ASC (Baltaxe & D’Angiola, 1996; Charney, 1980; Hauser et al., 2019; Kanner, 1943; Naigles et al., 2016) or with other conditions (Friedman, Lorang, et al., 2019), particularly at younger ages (Arnold et al., 2009). For example, children with ASC have been reported to produce fewer first and second person pronouns (“me”, and “you”) than intellectually disabled and typically developing comparison groups (Jordan, 1989). In 1994, Lee and colleagues showed that children with ASC produced the pronouns “you” and “me” at atypical rates, despite having no difficulties with pronoun comprehension. Rather than using pronouns, children were instead more likely than non-autistic control group subjects to use proper nouns to refer to the experimenters and themselves (Lee, Hobson, & Chiat, 1994). The gap between intact comprehension on one hand, and atypical production on the other, has also been reported in third person pronoun production (e.g., “him”, “her”; (Hobson et al., 2010)).

Studies hinting at a connection between social impairment and pronoun use suggest that differences in personal pronoun use could be an objective metric for assessing social phenotypes in children with ASC (Loveland & Landry, 1986). In the same study that examined third-person pronoun use by autistic children (Hobson et al., 2010), researchers examined the relationship between pronoun production and communicative engagement. A rater, blind to children’s diagnostic status, reviewed videotapes of the pronoun production tasks, and rated participants’ eye gaze direction during the tasks (i.e., orienting toward a third person or not), as well as interpersonal connectedness with their conversational partner. They found that subjects with autism and limited third-person pronoun production looked less at experimenters, and autistic participants who said “we” more often were rated higher on interpersonal connectedness (Hobson et al., 2010). These results suggest a potential link between pronoun use and social behavior in ASC, such that subtle verbal communication patterns – captured by first person and third person pronouns – might serve as objective markers of social phenotype.

Us vs. Them

Given that word choice is an index of attentional focus (Klin, 2000), and individuals with ASC show reduced social interest and motivation compared to TD controls (Chevallier et al., 2012), social deficits may be measurable in the words autistic children produce during natural conversations. First person plural and third person plural pronouns (“we” and “they” and their variants), in particular, could mark children’s degree of attentional focus on social groups, and may indicate awareness of membership in (“we”) – or exclusion from (“they”) – social groups. Indeed, prior literature suggests that first- and third-person plural pronouns are differentially associated with whether one perceives oneself to be part of a group – also known as one’s collective self-identification (Brewer & Gardner, 1996; Cramer & Schuman, 1975) – wherein “we” is associated with self-identified group membership, and “they” is associated with non-membership. This potentially meaningful social distinction has never been studied in ASC.

Current study

This study compares first- vs. third-person plural pronoun production in girls and boys with and without ASC during a short naturalistic conversation with a non-expert interlocutor. We specifically examine sex differences, because although a large literature exists on pronoun use in ASC, it is currently unknown whether pronoun use differs for all autistic children, since the aforementioned studies on pronoun use in ASC included few – if any – girls and women. Given diagnostic group differences in social motivation reported in the literature (ASC < TD; (Chevallier et al., 2012)), we hypothesized that autistic children and adolescents would produce fewer personal pronouns than TD children and adolescents (marking reduced social motivation and less attentional focus on social groups). However, recent research suggests that autistic girls may be more socially motivated than autistic boys (Sedgewick et al., 2016), leading us to hypothesize that ASC girls would produce more personal pronouns than ASC boys. We further hypothesized greater relative use of third-person plural pronouns (“they”, “them”) by autistic girls compared to autistic boys, given research suggesting that ASC girls often “hover” around the edges of social groups in school settings (Dean et al., 2017) and therefore might maintain heightened awareness of groups for which they are non-members (excluded). To understand the larger verbal context of potential pronoun differences, we analyzed “social” words to determine whether girls and boys also differed on their production of words from this broader language category. Finally, we hypothesized that pronoun use would correlate with social phenotype, such that greater attentional focus on social groups would be associated with fewer (or milder) autism symptoms. Given the paucity research on typical sex differences in plural pronoun use, we did not have specific sex-related hypotheses for the TD group. Of note, sex differences were expected in the ASC group despite the lack of hypotheses about sex differences in the TD group, as prior research suggests that more girls with ASC experience heightened social motivation and are more likely to camouflage their autism symptoms or engage in social compensation as compared to boys (Wood-Downie et al., 2020); these differences were expected to result in sex-differentiated social communication patterns for the ASC group specifically.

Methods

Participants

Eighty-seven matched participants with ASC and typically developing (TD) controls were selected from a pool of verbally fluent individuals who participated in one of many studies conducted at a large hospital-based research center. The larger series of studies included diagnostic tests, cognitive assessments, and language and motor tasks. To match groups, participants with complete data (age, sex, race, ADOS, IQ testing) were first selected from the larger pool; participants with full-scale IQ estimates below 78 were excluded; participants were excluded if they were younger than 8 years old, and excluded if they were older than 17 years old. ASC diagnoses were made by expert PhD-level clinicians using the clinical best estimate (CBE) approach (Lord, Petkova, et al., 2012), with support from a research-reliable administration of the ADOS-2 (Lord et al., 2012). The CBE method prioritizes DSM-V criteria informed by family/medical history and an evaluation by an autism specialist. The Center for Autism Research does not rely solely on ADOS cutoffs or SCQ scores when diagnosing ASC, nor do subthreshold scores lead to automatic disqualification for receiving an ASC diagnosis. This is because many conditions can result in elevated scores on these metrics (e.g., ADHD; (Grzadzinski et al., 2016)), and individuals – particularly girls – may exhibit profiles that do not hit algorithm items on standard ASC diagnostic measures (Ratto et al., 2017) but do meet DSM-V criteria. Thus, participants were included in the ASC group if they met DSM-V criteria as evaluated by PhD-level clinicians with specific expertise in ASC using the CBE method, and not included if they did not (some participants were excluded from the ASC group despite elevated scores on ADOS or SCQ, because the CBE diagnosis was not ASC). Participants were recruited through a variety of mechanisms, including public advertising, word of mouth, and re-recruitment from previous studies. Participants were excluded if they had a known genetic syndrome, history of concussion or brain injury that impacted current functioning, a gestational age below thirty-four weeks, or if English was not their primary language. Additionally, participants were excluded if parents reported that the child or adolescent had permanent motor damage from prior medication use (e.g., methamphetamines). Current medication use reported by parents of participants in the ASC group included SSRIs for 9 out of 50 participants, and antipsychotics for 6 out of 50 participants, with one participant taking both kinds of medications. The final sample included four groups, matched on age and IQ (girls with ASC, boys with ASC, TD girls, and TD boys; Table). ASC girls and boys were additionally matched on ADOS-2 total calibrated severity scores (CSS) and SCQ scores. Parents or primary caregivers were given an informed consent packet to review, and completed written informed consent upon arrival. Participants and parents were compensated for their time. All participants in this sample consented to their data being used for future studies; this study was overseen by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Table.

Participant characteristics showing sex ratio, self-reported racial group, and parental education distribution by diagnostic group, as well as mean (standard deviation), and minimum-maximum values for age, IQ, ADOS-2 calibrated severity scores (CSS), SCQ scores, and Vineland-2 (VABS-2) expressive vocabulary scaled scores by diagnostic group and sex. Chi-square tests were used to compare distributions of sex, race, and parent education between diagnostic groups, and t-tests compared mean values for continuous variables. The first subcolumn in the table (“Sex”) refers to overall comparisons between males and females collapsed across diagnostic group, the second (“Dx”) to overall comparisons between ASC and TD groups collapsed across sex, and the third (“Sex in ASC”) to a comparison of males and females in the ASC subgroup alone.

| ASC (N = 50) | TD (N = 37) | Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex ratio | 17f, 33m (66% Male) | 15f, 22m (59% Male) | χ2=0.16, p=0.69 | ||||

| Race | Black/African American: 3 Asian or Pacific Islander: 1 White/Caucasian: 40 Multiracial: 4 Other: 1 |

Black/African American: 8 Asian or Pacific Islander: 1 White/Caucasian: 23 Multiracial: 5 Other: 0 |

χ2=6.52, p=0.16 | ||||

| Maternal education (in years) | <=12 years: 3 13-16 years: 24 17+ years: 22 Unknown: 1 |

<=12 years: 2 13-16 years: 23 17+ years: 12 |

χ2=1.52, p=0.47 | ||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Sex | Dx | Sex in ASC | |

| Age (years) | 11.48 (2.38) 8.90-16.35 |

11.79 (2.55) 8.25-16.66 |

11.38 (2.44) 8.22-15.51 |

10.58 (2.44) 8.16-16.64 |

p=.74 d=−.07 |

p=.15 d=.32 |

p=.68 d=.13 |

| Full-Scale IQ | 109.76 (11.99) 79-130 |

105.27 (13.03) 79-131 |

105 (13.07) 86-129 |

109.68 (13.70) 86-133 |

p=.88 d=−.03 |

p=.74 d=−.07 |

p=.24 d=−.35 |

| Verbal IQ | 108.35 (11.66) 85-130 |

104.76 (13.17) 70-130 |

105.87 (14.34) 80-128 |

109.27 (14.78) 86-131 |

p=.87 d=−.04 |

p=.53 d=−.14 |

p=.35 d=−.28 |

| Non-verbal IQ | 108.24 (14.48) 80-130 |

104.55 (12.43) 80-130 |

103.07 (12.93) 81-122 |

107.68 (11.49) 89-130 |

p=.997 d=0 |

p=.997 d=0 |

p=.35 d=−.28 |

|

ADOS-2 CSS Total |

6.59 (2.69) 1-10 |

6.97 (2.01) 2-10 |

1.07 (0.26) 1-2 |

1.27 (0.46) 1-2 |

p=.43 d=.09 |

p<2e-16 d=3.27 |

p=.57 d=.17 |

| ADOS-2 SA CSS | 6.47 (2.62) 1-10 |

7.36 (1.76) 3-10 |

1.40 (0.74) 1-3 |

1.73 (0.83) 1-3 |

p=.09 d=.20 |

p<2e-16 d=3.22 |

p=.16 d=.43 |

| ADOS-2 RRB CSS | 7.35 (1.66) 5-10 |

6.30 (2.39) 1-10 |

1 (0) 1-1 |

2.09 (2.11) 1-7 |

p=.82 d=−.03 |

p<2e-16 d=2.50 |

p=.11 d=−.48 |

| SCQ Total * | 17.94 (7.11) 6-31 |

18.34 (6.79) 5-33 |

2.73 (2.52) 0-8 |

2.68 (3.27) 0-14 |

p=.87 d=.02 |

p<2e-16 d=2.81 |

p=.85 d=.06 |

| VABS-2* Expressive Voc | 13.94 (3.51) 7-20 |

12.45 (3.15) 7-18 |

17.00 (1.35) 14-19 |

17.18 (1.68) 13-19 |

p=.24 d=.27 |

p<.001 d=1.52 |

p=.14 d=.54 |

1 male participant from the ASC group was missing an SCQ score; 2 female participants from the TD group were missing VABS-2 Expressive Vocabulary scaled scores.

Study procedure

Linguistic data were drawn from a 5-minute conversation between the participant and study personnel (confederate), administered as part of a larger study. The conversation was completely unstructured with no specific topics provided to either speaker. Twenty-three young adult confederates (21 females; undergraduate students and research assistants) were assigned to each participant based on availability (there were no significant differences in confederate sex distribution by participant sex or diagnostic group). Confederates were not informed of participant diagnosis, and their only instructions were to act natural and avoid dominating the conversation. To account for potential individual differences in confederate behavior, a random effect of confederate ID was included in all analyses. At the start of the conversation, the research assistant in charge of the visit said a variation of the phrase, “You two just chat and get to know each other. I’m going to finish getting a few things set up.” Conversations were audio/video recorded using a device with two HD video cameras and mics facing opposite directions, placed on a table between participants and confederates for simultaneous capture of both speakers (Parish-Morris et al., 2018).

Measures

Participants in the study were administered a battery of diagnostic and cognitive tests including the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule Second Edition (ADOS-2; (Lord, DiLavore, et al., 2012). Either ADOS-2 module 3 or 4 was administered to participants in this study by a research-reliable clinician. ADOS-2 scores index two domains, Social Affect (SA) and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors (RRBs), with higher scores indicating greater symptoms (Hus et al., 2014). The Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) – Lifetime version is a yes/no parent response questionnaire that asks parents or primary caregivers to assess their child’s social behaviors associated with ASC (Rutter et al., 2003), and was given to a parent/primary caregiver to fill out prior to clinical assessment.

Participant IQ estimates were calculated using one of the following tests, which were administered based on the protocol requirements of individual studies that were pooled across a large research center to generate the current sample: 57 participants (35 TD, 24 ASC) received the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, Second Edition (Wechsler, 2011), 3 participants (3 ASC) received the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fifth Edition (Wechsler, 2014), 21 participants (21 ASC) received the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (Roid, 2003), 4 participants received the Differential Ability Scales, Second Edition (DAS-II, DAS-II School version (2 TD, 1 ASC)), or DAS-II Early version (1 ASC) used depending on age; Elliot, 2007). Scores were standardized by a licensed neuropsychologist (J. Pandey) to create an overall cognitive estimate, a verbal estimate, and a nonverbal estimate.

Data processing

Audio recordings of each conversation were segmented, labeled by speaker, and orthographically transcribed using XTrans (Linguistic Data Consortium, 2018) (see Appendix S1). Average word-level transcription reliability was calculated for 20% of the samples, and averaged 97.22% (range: 95.70% - 98.53%). After segmentation, speaker labeling, and transcription, words produced by participant and confederate were separated using an in-house R script. Files were fed into LIWC software (Pennebaker et al., 2015), which calculated the overall number of words produced, as well as the number of first- and third-person plural pronouns and “social” category words produced by each speaker (see Dependent variables, below).

Statistical approach

Data were analyzed using generalized linear mixed effects regression (GLMER) models in R (‘lme4’ package; R Core Team and contributors worldwide) with age and IQ (mean centered) as covariates, a random effect of confederate ID for separate “we”, “they”, and “social” variant analyses, and random effects of both participant ID and confederate ID for the primary omnibus test comparing “we” versus “they” production (since participants produced both types of pronouns during every conversation). Estimated effects, standard errors (SE), z-values, and p-values are provided. Variables were coded as follows: TD=0, ASC=1; Female=0, Male=1. Dependent variables were positive, interval, and non-normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk test ps<.001), so these data were modeled using a Poisson distribution with a log link. Significance values for planned pairwise tests of GLMER estimated marginal means were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Tukey method. Effect sizes for GLMER are reported as unstandardized effects (estimates; Pek & Flora, 2018), while Cohen’s d is reported for group mean differences on clinical and demographic variables (Table). Following Cohen (1988), d=0.2 is considered a “small” effect, d=0.5 a “medium” effect, and d=0.8 a “large” effect (Cohen, 1988). GLMER was used to assess relationships between pronoun production and clinical phenotype (ADOS-2 Social Affect and Repetitive Behaviors domain scores).

Dependent variables

Preliminary analyses controlling for age and IQ (mean centered), and confederate ID revealed that participant groups produced significantly different numbers of words during the 5-minute conversations (Table S1). Thus, subsequent analyses were conducted on the number of first-person plural pronouns (“we”, “us” and variants), third-person plural pronouns (“they”, “them” and variants), and “social” category words as calculated by LIWC (see Appendix S2), normalized per 1000 words to account for varying word production across conversations and to facilitate interpretation. We decided to normalize word use per 1000 words based on the average range of words produced by participants in our study, and to illustrate relative frequency without reporting percentages that could be misinterpreted when participants produced fewer overall words. We further avoided the use of proportions because they tend to violate the underlying assumptions of common statistical tests, can be misleading when the number of words produced varies widely (as in this study and most studies of productive language in ASC), and do not generally adhere to the way words are counted (usually full words are counted as words, and thus are better represented as count data than as decimals). Clinical phenotype was measured using ADOS-2 CSS scores.

Results

A generalized linear mixed effects regression predicting pronoun use revealed a significant three-way interaction between sex, diagnosis, and pronoun type (estimate: −.94, SE=.18, z=−5.13, p<.001; controlling for age and IQ (centered), with participant and confederate IDs as random effects to account for repeated measures). Conditional main effects of diagnosis (estimate: −.71, SE: .24, z=−2.91, p=.004), sex (estimate: −.43, SE: .23, z=−1.91, p=.056), and pronoun type (“they” estimate: −.94, SE: .10, z=−9.53, p<.001) on overall pronoun use emerged. To clarify the nature of the interaction, subsequent analyses were conducted within each pronoun type separately.

First person plural (“we” variants)

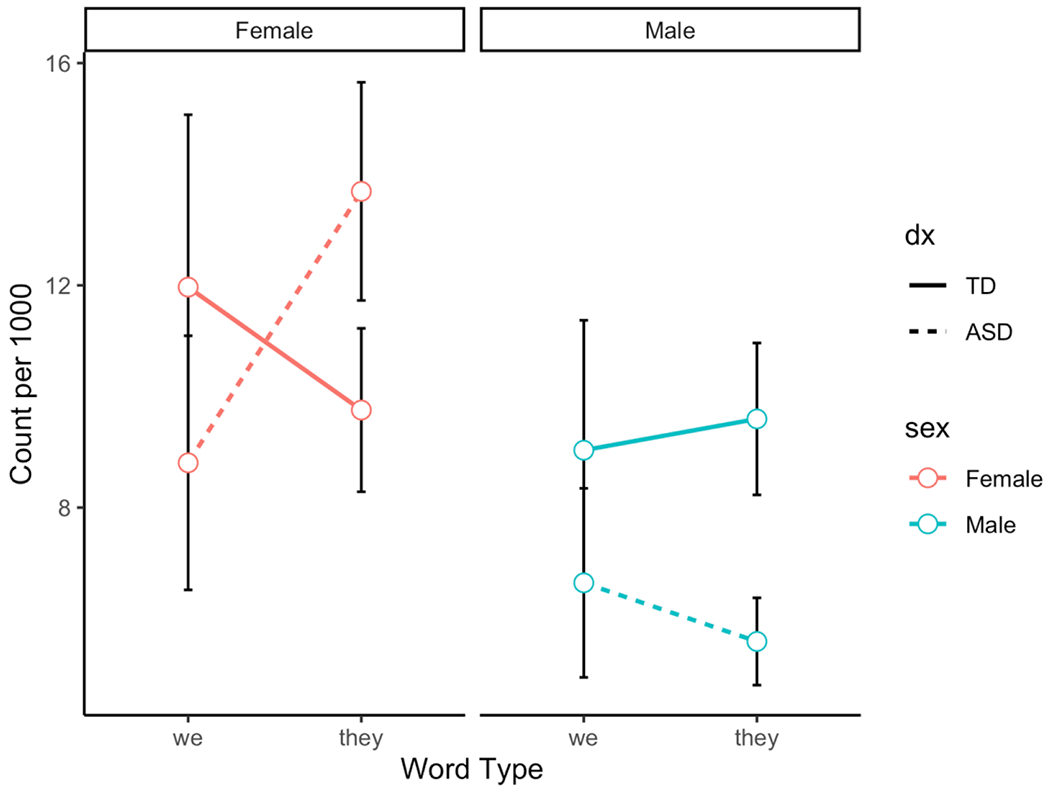

A GLMER including confederate ID, age, IQ, sex, diagnosis, and the interaction between sex and diagnosis revealed a nonsignificant interaction effect, so this factor was removed from the model. The final model with sex and diagnosis predicting “we” production per 1000 words revealed a significant main effect of diagnosis (estimate: −.31, SE: .07, z=−4.25, p< .001; Table S1), such that participants with ASC produced less “we” than TD participants. A significant effect of sex also emerged; boys were less likely to produce “we” variants than girls (estimate: −.28, SE: .07, z=−4.28, p<.001). Tukey-corrected pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means revealed that “we” production differed significantly in all subgroups except ASC girls and TD boys, who did not differ significantly from one another (TD girls>TD boys=ASC girls>ASC boys; Figure; Table S1).

Figure.

Estimated marginal means (EMM) and standard errors (error bars) of “we” variant production and “they” variant production per 1000 words in girls and boys with and without ASC, in two separate models accounting for age, full-scale IQ, and confederate ID.

Third person plural (“they” variants)

A GLMER including confederate ID, age, IQ, sex, diagnosis, and the interaction between sex and diagnosis revealed a significant interactive effect of sex and diagnosis on “they” variants produced per 1000 words (estimate: −.88, SE: .18, z=−4.92, p<.001). Tukey-corrected pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means revealed that the interaction was driven by significantly increased relative “they” production in autistic girls (Figure; Table S1), such that autistic girls used significantly more “they” than autistic boys (estimate: .90, SE: .12, z=7.39, p<.0001; Table S1), TD girls (estimate: −.34, SE: .13, z=−2.65, p=.04), and TD boys (estimate: .36, SE: .11, z=2.98, p=.02). “They” production by TD girls and boys did not differ from one another (estimate: .02, SE: .13, z=.13, p=.99; ASC girls > TD girls = TD boys > ASC boys; Figure; Table S1).

“Social” category words

To understand the broader context of differences in pronoun use, we explored the amount of social talk produced by each participant by analyzing “social” category words as measured by LIWC. A GLMER including age, IQ, sex, diagnosis, confederate ID, and the interaction between sex and diagnosis revealed a significant interactive effect of sex and diagnosis on “social” words produced per 1000 words (estimate: −.25, SE: .06, z=−4.52, p<.001). Tukey-corrected pairwise comparisons of estimated marginal means revealed that the interaction was driven by reduced social word production in ASC boys (Mean=71.47) compared to ASC girls (Mean=92.45, z=6.77, p<.0001), TD boys (Mean=94.62, z=7.48, p<.0001), and TD girls (Mean=95.26, z=7.58, p<.0001). Rates of social word use by ASC girls, TD girls, and TD boys did not differ significantly from one another (all ps>.88). Thus, we found that ASC boys produced distinctly lower levels of social talk, while ASC girls, TD girls, and TD boys produced patterns of social talk that did not differ significantly from one another. This analysis provides convergent evidence for differential social language phenotypes in boys and girls with and without ASC, and suggests a connection between differential rates of pronoun production and social language more broadly.

Predicting clinical phenotype

To determine whether pronoun production was associated with clinical phenotype in ASC, pronouns were used to predict ADOS-2 scores in the ASC group alone. After controlling for age and IQ (centered), with random effects of participant ID and confederate ID, a GLMER revealed that “we” variants and “they” variants significantly predicted ADOS-2 social affect (SA) CSS scores in the ASC group (“we” estimate: −.01, SE=.006, z=−2.38, p=.02; “they” estimate: −.01, SE: .007, z=−2.21, p=.03). A separate GLMER revealed that “we” and “they” variants did not significantly predict ADOS-2 repetitive behavior (RRB) scores (all ps>.19), suggesting that pronoun use is specifically associated with social function and not repetitive behaviors. Exploratory subgroup analyses in ASC boys and girls separately showed that the relationship between ADOS-2 SA scores in the overall ASC sample was driven by significant linkages between pronoun use and ADOS-2 SA scores in autistic girls (“we” estimate: −.02, SE=.01, z=−1.87, p=.06; “they” estimate: −.03, SE: .01, z=2.75, p=.006). Prediction in autistic boys was nonsignificant (all ps>.21), although these results should be viewed with caution due to the small sample sizes in each subgroup.

Discussion

This study is the first to compare plural pronoun use by girls and boys with and without ASC, and one of the few in the literature to analyze language produced by autistic children and adolescents during brief conversations with non-expert interlocutors. A number of notable findings emerged: First, we found that as a group, autistic children and adolescents used significantly fewer plural personal pronouns than matched TD peers. This main effect of autism on personal pronoun production is broadly consistent with reports of reduced social motivation and social attention in autism (Chevallier et al., 2012). Based on this finding and consistent with prior research, reduced or atypical personal pronoun use appears to be a good diagnostic marker for ASC, and may – pending future research in younger children – prove clinically useful for lowering the age of first autism diagnosis. Our second finding revealed important – and previously unreported – nuances in personal pronoun use that varied by sex in ASC.

Sex differences in word use emerged for both first- and third-person plural pronouns in ASC, with girls consistently producing more social group-related talk compared to boys. One explanation for this finding is that autistic girls are hyperaware of groups they are (and are not) not included in, while ASC boys – who produced diminished social group talk across the board – are comparatively less likely to talk about social topics, regardless of group membership status. This conclusion is consistent with research showing that girls with ASC tend to hover around social groups on the playground and be neglected socially – in contrast to ASC boys who tend to be alone and rejected (Dean et al., 2014, 2017). Our pattern of findings could also be interpreted as evidence of social camouflage or compensation, which may be more common in females than males with ASC (Allely, 2018) and may or may not be consciously deployed. From that perspective, ASC girls with heightened “they” production might have learned to match TD levels of social talk as a way to blend in linguistically with peers – thus partially “normalizing” natural speech (Parish-Morris et al., 2017).

Sex differences in plural pronoun use by TD children and adolescents were also revealed, such that TD girls talked more about social groups they were a part of ( “we” variants) than did TD boys. Long-researched sex differences in friendship structure during childhood and adolescence may underlie the greater amounts of “we” talk observed in girls relative to boys in both diagnostic groups, which is also consistent with recent research showing that the friendship structures of ASC girls and boys differ along typical lines (Sedgewick et al., 2016, 2019). In contrast to the sex-differentiated patterns of “they” production observed in ASC, however, there was no effect of sex on the amount of talk by TD boys and girls about social groups they are not a part of (i.e., both sexes were equally likely to use “they” variants). This suggests that sex differences in “they” production by children and adolescents in the ASC group may be autism-specific.

Interestingly, autistic girls in our sample produced significantly more third-person plural pronouns (“they”, “them”) than TD girls, which could indicate even greater-than-average social interest and motivation. However, autistic girls’ heightened focus on social groups (increased “they”) may be complicated by their diminished membership in those groups (diminished “we”) relative to same-sex TD peers. This tension – between heightened awareness of social groups on one hand, and reduced membership on another – could index social exclusion, which may contribute to elevated levels of depression and anxiety in girls with ASC (Bargiela et al., 2016). Recent research supports this interpretation, as the friendship structures of girls and boys have been shown to vary systematically in ways that drive sex-differentiated friendship experiences in ASC (Sedgewick et al., 2019). Thus, when it comes to identifying girls with ASC vs. typical girls, our results suggest that while the overall amount of talk about social groups is high in both populations, and might therefore not be a reliable marker for whether or not a girl should be referred for an autism evaluation, how girls talk about social groups might be a good indicator of social function that could be used to guide clinical decision-making.

In line with recent research showing that autistic girls experience enhanced social motivation relative to autistic boys (Sedgewick et al., 2016), we found that autistic girls produced significantly more social words than autistic boys did – not just personal pronouns – indicating generally heightened conversational attention to social topics. Sex differences in language markers of social motivation in autism are especially important in light of the late (Baio et al., 2018) or missed (Loomes et al., 2017) diagnoses that are common for autistic girls and women. Specifically, heightened talk about social topics could complicate ASC referral and diagnosis when observers expect a male-centric “autistic” behavioral pattern of reduced social motivation and attention to social groups, which ASC girls do not necessarily exhibit.

Finally, our study showed that pronoun use predicts social phenotype in autistic girls, such that greater attentional focus on social groups predicts fewer (or milder) autism symptoms as rated by an expert clinician. This relationship was not present in autistic boys, perhaps due to the restricted range of pronoun production in that subgroup. Despite deliberately matching boys and girls on overall autism symptoms, boys in our sample were significantly less likely than girls to use both types of plural pronouns. Thus, while the social phenotype of girls with ASC appears measurable via personal pronoun production during brief conversations, it may be more difficult to assess in boys (at least, using personal pronouns as a metric).

Limitations and future directions

A number of notable strengths distinguish this study from prior research, including sufficient numbers of ASC and TD girls and boys to analyze diagnosis- and sex-based differences in pronoun use. However, certain limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, although our sample included a greater-than-average percentage of autistic girls (33% of the ASC group), this study bears replication with larger samples. Future research in our lab is planned, which will expand this approach to include more participants in semi-structured question-and-answer formats, such as the ADOS-2 social interview section. This approach – with standardized social prompts – would increase the likelihood that social prompting is conducted in approximately the same way across participants and would reduce the need to control for variable confederate behavior. However, a standardized interview administered by an expert is also less generalizable to everyday life experiences. Second, it is still unknown whether these effects will hold in older and younger samples, and in samples with lower IQ estimates. A developmentally-matched comparison group (e.g., with Down syndrome) would allow us to extend our IQ range, and pilot research using this approach with ASC and TD children as young as 5 years old is currently underway. Our sample also lacked the power to determine whether medication use (e.g., SSRIs) may have an effect on pronoun use, which is a promising avenue for future research. Third, the girls in this sample were identified as autistic during childhood despite a recognized problem of late and missed diagnoses for females (Baio et al., 2018; Loomes et al., 2017). Thus, the girls in this sample may differ systematically from autistic girls who are diagnosed later, during adolescence in adulthood, and it is unknown whether or not these findings generalize to later-diagnosed or undiagnosed girls and women on the spectrum. Fourth, it is important to further analyze what kind of group-focused talk children produced. Although girls with ASC produced social category words at rates that did not differ from TD girls, it is nonetheless possible that girls with ASC spoke about social groups in ways that differed qualitatively – if not quantitatively – from TD girls (e.g., differential reliance on proper nouns vs. pronouns (Lee et al., 1994), variable talk about friends vs. family, or use of they as a gender neutral pronoun). Future research will examine qualitative differences in the social group-related talk in ASC and TD boys and girls. Fifth, our study did not measure the real-world effects of variable pronoun production, which may differentially impact the peer experiences of boys vs. girls; future research is necessary to tease apart relationships between sex-differentiated peer social contexts and demands on the one hand, and language behavior on the other. Sixth, our measure of social phenotype (ADOS-2 social affect total score) is not designed to be a dimensional measure of social phenotype. A targeted questionnaire about social interest and motivation, or a behavioral measure like attention to social stimuli during eye tracking, might correlate more strongly with pronoun use. Finally, given the lack of validated social camouflaging or compensation measures for participants in our age range, we do not have self-report of this behavior; this limits our ability to interpret word-level differences as being due to this phenomenon.

Conclusion

Our study addresses multiple gaps in the literature by exploring personal pronouns as linguistic markers of social phenotype in brief spontaneous conversations of autistic girls and boys, as compared to an adequately powered sample of matched typically developing peers. Building on previous research demonstrating correlations between personal pronoun use and social ability in ASC, this study showed that markers of social phenotype can be extracted from short natural language samples – at least for girls; boys may require different metrics. Understanding and quantifying sex differences in expressive language in ASC will lead to more accurate phenotyping for boys and girls, which is necessary to improve early identification and inform personalized, sex-sensitive interventions that maximize long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Data processing.

Appendix S2. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count.

Table S1. Estimated marginal means (EMM) and standard errors (SE) from a final model predicting overall participant word count, and two models predicting “we” and “they” variants normalized per 1000 words.

Acknowledgements

In this paper, the authors’ terminology is drawn from World Health Organization definitions, such that the word “sex” refers to genetic makeup, and “gender” refers to a socio-cultural construct (World Health Organization, 2015); the authors use the words “girl” and “boy” to refer to sex as reported by parents. In line with preferences expressed by self-advocates and parents within the autistic community (Brown, 2011; Dunn & Andrews, 2015; Kenny et al., 2016), this paper uses both identity-first language (i.e. autistic girls and boys) and person-first language (i.e. girls and boys with autism). The authors thank the children and families who participated in this study, as well as students, interns, volunteers, postdocs, clinicians, and administrative staff at the Center for Autism Research, as well as their funding sources: NIDCD R01DC018289 (PI: J.P-M.) and a CHOP Research Institute Director’s Award to J.P-M.; and the Allerton Foundation (PI: R.T.S.), and NICHD 5U54HD086984 (MPI: Robinson & R.T.S.) to R.T.S. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article:

References

- Allely CS (2018). Understanding and recognising the female phenotype of autism spectrum disorder and the “camouflage” hypothesis: A systematic PRISMA review. Advances in Autism, 5(1), 14–37. 10.1108/AIA-09-2018-0036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JE, Bennetto L, & Diehl JJ (2009). Reference production in young speakers with and without autism: Effects of discourse status and processing constraints. Cognition, 110(2), 131–146. 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr H, Milbury K, Majeed N, Carmack CL, Ahmad Z, & Gritz ER (2016). Natural language use and couples’ adjustment to head and neck cancer. Health Psychology, 35(10), 1069–1080. 10.1037/hea0000377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, Kurzius-Spencer M, Zahorodny W, Robinson C Rosenberg, White T, Durkin MS, Imm P, Nikolaou L, Yeargin-Allsopp M, Lee L-C, Harrington R, Lopez M, Fitzgerald RT, … Dowling NF (2018). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2014. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1–23. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltaxe CA, & D’Angiola N (1996). Referencing skills in children with autism and specific language impairment. European Journal of Disorders of Communication: The Journal of the College of Speech and Language Therapists, London, 31(3), 245–258. 10.3109/13682829609033156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargiela S, Steward R, & Mandy W (2016). The Experiences of Late-diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. 10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beggiato A, Peyre H, Maruani A, Scheid I, Rastam M, Amsellem F, Gillberg CI, Leboyer M, Bourgeron T, Gillberg C, & Delorme R (2017). Gender differences in autism spectrum disorders: Divergence among specific core symptoms. Autism Research: Official Journal Of The International Society For Autism Research, 10(4), 680–689. 10.1002/aur.1715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn K, Brody N, & LeFebvre L (2014). The I’s, We’s, and She/He’s of Breakups: Public and Private Pronoun Usage in Relationship Dissolution Accounts. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(2), 202–213. 10.1177/0261927X13516865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boals A, & Klein K (2005). Word Use in Emotional Narratives about Failed Romantic Relationships and Subsequent Mental Health. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 24(3), 252–268. 10.1177/0261927X05278386 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boorse J, Cola M, Plate S, Yankowitz L, Pandey J, Schultz RT, & Parish-Morris J (2019). Linguistic markers of autism in girls: Evidence of a “blended phenotype” during storytelling. Molecular Autism, 10(1), 14. 10.1186/s13229-019-0268-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, & Gardner W (1996). Who is this “We”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83–93. 10.1037/0022-3514.71.1.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmeyer T, Zimmermann J, Kulessa D, Hautzinger M, Bents H, Friederich H-C, Herzog W, & Backenstrass M (2015). Me, myself, and I: Self-referent word use as an indicator of self-focused attention in relation to depression and anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L (2011). Identity-First Language Autistic Self Advocacy; Network. http://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/identity-first-language/ [Google Scholar]

- Charney R (1980). Pronoun errors in autistic children: Support for a social explanation. The British Journal of Disorders of Communication, 15(1), 39–43. 10.3109/13682828009011369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier C, Kohls G, Troiani V, Brodkin ES, & Schultz RT (2012). The social motivation theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(4), 231–239. 10.1016/j.tics.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C, & Pennebaker JW (2007). The psychological functions of function words. Social Communication, 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Clements CC, Zoltowski AR, Yankowitz LD, Yerys BE, Schultz RT, & Herrington JD (2018). Evaluation of the Social Motivation Hypothesis of Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(8), 797. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edition). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cola ML, Plate S, Yankowitz L, Petrulla V, Bateman L, Zampella CJ, de Marchena A, Pandey J, Schultz RT, & Parish-Morris J (2020). Sex differences in the first impressions made by girls and boys with autism. Molecular Autism, 11(1). 10.1186/s13229-020-00336-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer MR, & Schuman H (1975). We and they: Pronouns as measures of political identification and estrangement. Social Science Research, 4(3), 231–240. 10.1016/0049-089X(75)90013-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall MC, McDaniel J, Watson LR, & Yoder PJ (2019). The Relation Between Early Parent Verb Input and Later Expressive Verb Vocabulary in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(6), 1787–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D, & Brock TC (1975). Use of first person pronouns as a function of increased objective self-awareness and performance feedback. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11(4), 381–388. 10.1016/0022-1031(75)90017-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Harwood R, & Kasari C (2017). The art of camouflage: Gender differences in the social behaviors of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(6), 678–689. 10.1177/1362361316671845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Kasari C, Shih W, Frankel F, Whitney R, Landa R, Lord C, Orlich F, King B, & Harwood R (2014). The peer relationships of girls with ASD at school: Comparison to boys and girls with and without ASD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1218–1225. 10.1111/jcpp.12242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn DS, & Andrews EE (2015). Person-first and identity-first language: Developing psychologists’ cultural competence using disability language. American Psychologist, 70(3), 255–264. 10.1037/a0038636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworzynski K, Ronald A, Bolton P, & Happé F (2012). How different are girls and boys above and below the diagnostic threshold for autism spectrum disorders? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(8), 788–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot CD (2007). Differential Ability Scales®-II - DAS-II. Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L, Lorang E, & Sterling A (2019). The use of demonstratives and personal pronouns in fragile X syndrome and autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 33(5), 420–436. 10.1080/02699206.2018.1536727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman L, Sterling A, DaWalt LS, & Mailick MR (2019). Conversational Language Is a Predictor of Vocational Independence and Friendships in Adults with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4294–4305. 10.1007/s10803-019-04147-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard L, Dritschel B, & Howlin P (2014). A preliminary study of gender differences in autobiographical memory in children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2087–2095. 10.1007/s10803-014-2109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman K, Olson L, Hill AP, Lunsford R, Heeman PA, & van Santen JPH (2016). “Uh” and “um” in children with autism spectrum disorders or language impairment. Autism Research, n/a-n/a. 10.1002/aur.1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzadzinski R, Dick C, Lord C, & Bishop S (2016). Parent-reported and clinician-observed autism spectrum disorder (ASD) symptoms in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Implications for practice under DSM-5. Molecular Autism, 7(1). 10.1186/s13229-016-0072-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop C, Jones DR, Sasson NJ, Zheng S, Nowell SW, & Parish-Morris J (2020). Social and Object Attention Is Influenced by Biological Sex and Toy Gender-Congruence in Children With and Without Autism. Autism Research, 13(5), 763–776. 10.1002/aur.2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop C, Jones D, Zheng S, Nowell S, Schultz R, & Parish-Morris J (2019). Visual attention to faces in children with autism spectrum disorder: Are there sex differences? Molecular Autism, 10(1). 10.1186/s13229-019-0276-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M, Sariyanidi E, Tunc B, Zampella C, Brodkin E, Schultz R, & Parish-Morris J (2019). Using natural conversations to classify autism with limited data: Age matters. Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology, 45–54. https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W19-3006 [Google Scholar]

- Hobson RP, Lee A, & Hobson JA (2010). Personal Pronouns and Communicative Engagement in Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(6), 653–664. 10.1007/s10803-009-0910-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hus V, Gotham K, & Lord C (2014). Standardizing ADOS Domain Scores: Separating Severity of Social Affect and Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2400–2412. 10.1007/s10803-012-1719-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine CA, Eigsti I-M, & Fein DA (2016). Uh, Um, and Autism: Filler Disfluencies as Pragmatic Markers in Adolescents with Optimal Outcomes from Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 1061–1070. 10.1007/s10803-015-2651-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan RR (1989). An experimental comparison of the understanding and use of speaker-addressee personal pronouns in autistic children. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 24(2), 169–179. 10.3109/13682828909011954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacewicz E, Pennebaker JW, Davis M, Jeon M, & Graesser AC (2014). Pronoun Use Reflects Standings in Social Hierarchies. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(2), 125–143. 10.1177/0261927X13502654 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanner L (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauschke C, van der Beek B, & Kamp-Becker I (2016). Narratives of Girls and Boys with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Gender Differences in Narrative Competence and Internal State Language. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 840–852. 10.1007/s10803-015-2620-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny L, Hattersley C, Molins B, Buckley C, Povey C, & Pellicano E (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. 10.1177/1362361315588200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa C, & Lehrer A (1990). Impersonal uses of personal pronouns. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(5), 739–759. 10.1016/0378-2166(90)90004-W [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B, Kleim B, Horn AB, Kraehenmann R, Mehl MR, & Ehlers A (2018). Early linguistic markers of trauma-specific processing indicate vulnerability for later chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klin A (2000). Attributing social meaning to ambiguous visual stimuli in higher-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome: The Social Attribution Task. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 41(7), 831–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Hobson RP, & Chiat S (1994). I, you, me, and autism: An experimental study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(2), 155–176. 10.1007/BF02172094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linguistic Data Consortium. (2018). XTrans. https://www.ldc.upenn.edu/language-resources/tools/xtrans [Google Scholar]

- Loomes R, Hull L, & Mandy WPL (2017). What Is the Male-to-Female Ratio in Autism Spectrum Disorder? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 466–474. 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, DiLavore PC, Gotham K, Guthrie W, Luyster RJ, Risi S, & Rutter M (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule: ADOS-2. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Petkova E, Hus V, Gan W, Lu F, Martin DM, Ousley O, Guy L, Bernier R, Gerdts J, Algermissen M, Whitaker A, Sutcliffe JS, Warren Z, Klin A, Saulnier C, Hanson E, Hundley R, Piggot J, … Risi S (2012). A Multi-Site Study of the Clinical Diagnosis of Different Autism Spectrum Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(3), 306–313. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, & Bishop SL (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, second edition (ADOS-2). Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Loveland KA, & Landry SH (1986). Joint attention and language in autism and developmental language delay. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 16(3), 335–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons M, Aksayli ND, & Brewer G (2018). Mental distress and language use: Linguistic analysis of discussion forum posts. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 207–211. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maenner MJ, & et al. (2020). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries, 69. 10.15585/mmwr.ss6904a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDuffie AS, Yoder PJ, & Stone WL (2006). Fast-mapping in young children with autism spectrum disorders. 26(4), 421–438. 10.1177/0142723706067438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller E, Schuler A, & Yates GB (2008). Social challenges and supports from the perspective of individuals with Asperger syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. Autism, 12(2), 173–190. 10.1177/1362361307086664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naigles LR, Cheng M, Xu Rattanasone N, Tek S, Khetrapal N, Fein D, & Demuth K (2016). “You’re telling me!” The prevalence and predictors of pronoun reversals in children with autism spectrum disorders and typical development. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 27, 11–20. 10.1016/j.rasd.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neysari M, Bodenmann G, Mehl MR, Bernecker K, Nussbeck FW, Backes S, Zemp M, Martin M, & Horn AB (2016). Monitoring Pronouns in Conflicts. GeroPsych, 29(4), 201–213. 10.1024/1662-9647/a000158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nook EC, Schleider JL, & Somerville LH (2017). A linguistic signature of psychological distancing in emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(3), 337. 10.1037/xge0000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish-Morris J, Liberman MY, Cieri C, Herrington JD, Yerys BE, Bateman L, Donaher J, Ferguson E, Pandey J, & Schultz RT (2017). Linguistic camouflage in girls with autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Autism, 8(1). 10.1186/s13229-017-0164-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish-Morris J, Sariyanidi E, Zampella C, Bartley GK, Ferguson E, Pallathra AA, Bateman L, Plate S, Cola M, Pandey J, Brodkin ES, Schultz RT, & Tunc B (2018). Oral-Motor and Lexical Diversity During Naturalistic Conversations in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Keyboard to Clinic, 147–157. 10.18653/v1/W18-0616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pek J, & Flora DB (2018). Reporting effect sizes in original psychological research: A discussion and tutorial. Psychological Methods, 23(2), 208. 10.1037/met0000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW (2011). The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say About Us. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Boyd RL, Jordan K, & Blackburn K (2015). The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/31333 [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mehl MR, & Niederhoffer KG (2003). Psychological Aspects of Natural Language Use: Our Words, Our Selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 547–577. 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin R, & Shaw R (1988). Narcissism and the Use of Personal Pronouns. Journal of Personality, 56(2), 393–404. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1988.tb00892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratto AB, Kenworthy L, Yerys BE, Bascom J, Wieckowski AT, White SW, Wallace GL, Pugliese C, Schultz RT, Ollendick TH, Scarpa A, Seese S, Register-Brown K, Martin A, & Anthony LG (2017). What About the Girls? Sex-Based Differences in Autistic Traits and Adaptive Skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 10.1007/s10803-017-3413-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochon E, Saffran EM, Berndt RS, & Schwartz MF (2000). Quantitative Analysis of Aphasic Sentence Production: Further Development and New Data. Brain and Language, 72(3), 193–218. 10.1006/brln.1999.2285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH (2003). Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition. Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Rose V, Trembath D, Keen D, & Paynter J (2016). The proportion of minimally verbal children with autism spectrum disorder in a community-based early intervention programme. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research: JIDR, 60(5), 464–477. 10.1111/jir.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Fuller E, Kasari C, Chamberlain B, & Locke J (2010). Social involvement of children with autism spectrum disorders in elementary school classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(11), 1227–1234. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rude S, Gortner E-M, & Pennebaker J (2004). Language use of depressed and depression-vulnerable college students. Cognition and Emotion, 18(8), 1121–1133. 10.1080/02699930441000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, & Lord C (2003). Social communication questionnaire (SCQ). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewicz A, Schuller B, Marchi E, Piana S, Camurri A, Lassalle A, & Baron-Cohen S (2016). An investigation of the ‘female camouflage effect’ in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism, 7(1). 10.1186/s13229-016-0073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F, Hill V, & Pellicano E (2019). ‘It’s different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism, 23(5), 1119–1132. 10.1177/1362361318794930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F, Hill V, Yates R, Pickering L, & Pellicano E (2016). Gender Differences in the Social Motivation and Friendship Experiences of Autistic and Non-autistic Adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1297–1306. 10.1007/s10803-015-2669-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons RA, Gordon PC, & Chambless DL (2005). Pronouns in Marital Interaction: What Do “You” and “I” Say About Marital Health? Psychological Science, 16(12), 932–936. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturrock A, Yau N, Freed J, & Adams C (2019). Speaking the Same Language? A Preliminary Investigation, Comparing the Language and Communication Skills of Females and Males with High-Functioning Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 10.1007/s10803-019-03920-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager-Flusberg H, & Kasari C (2013). Minimally Verbal School-Aged Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: The Neglected End of the Spectrum: Minimally verbal children with ASD. Autism Research, 6(6), 468–478. 10.1002/aur.1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Campbell WK, & Gentile B (2012). Male and Female Pronoun Use in U.S. Books Reflects Women’s Status, 1900–2008. Sex Roles, 67(9), 488–493. 10.1007/s11199-012-0194-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AR, Defteralı Ç, Bak TH, Sorace A, McIntosh AM, Owens DGC, Johnstone EC, & Lawrie SM (2012). Use of second-person pronouns and schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(4), 342–343. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.095448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2011). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence®—Second Edition (WASI®- II). Pearson Clinical. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2014). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children®-Fifth Edition. Pearson Clinical. [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Downie H, Wong B, Kovshoff H, Mandy W, Hull L, & Hadwin JA (2020). Sex/Gender Differences in Camouflaging in Children and Adolescents with Autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Fact sheet on gender: Key facts, impact on health, gender equality in health and WHO response. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/gender [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Data processing.

Appendix S2. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count.

Table S1. Estimated marginal means (EMM) and standard errors (SE) from a final model predicting overall participant word count, and two models predicting “we” and “they” variants normalized per 1000 words.