Abstract

Asymmetric cell division (ACD) requires protein polarization in the mother cell to produce daughter cells with distinct identities (cell-fate asymmetry). Here, we define a previously undocumented mechanism for establishing cell-fate asymmetry in Arabidopsis stomatal stem cells. In particular, we show that polarization of the protein phosphatase BSL1 promotes stomatal ACD by establishing kinase-based signalling asymmetry in the two daughter cells. BSL1 polarization in the stomatal ACD mother cell is triggered at the onset of mitosis. Polarized BSL1 is inherited by the differentiating daughter cell, where it suppresses cell division and promotes cell-fate determination. Plants lacking BSL proteins exhibit stomatal overproliferation, which demonstrates that the BSL family plays an essential role in stomatal development. Our findings establish that BSL1 polarization provides a spatiotemporal molecular switch that enables cell-fate asymmetry in stomatal ACD daughter cells. We propose that BSL1 polarization is triggered by an ACD checkpoint in the mother cell that monitors the establishment of division-plane asymmetry.

During the development of multicellular organisms, stem cells undergo self-renewing asymmetric cell division (ACD) to generate diverse cell types1,2. During ACD, the division of a progenitor cell (mother cell) yields one daughter cell identical to the progenitor and one differentiating daughter cell that adopts a distinct identity. Thus, in contrast to symmetric cell division, which yields two daughter cells identical to the progenitor, ACD requires cellular processes that establish cell-fate asymmetry3,4. The asymmetric distribution, or polarization, of factors in the progenitor cell provides a mechanism by which cell-fate determinants can be asymmetrically distributed between daughter cells. Protein polarization may enable cell-fate determinants to be sequestered in a location within the progenitor cell that is partitioned to one of the two daughter cells after division. Accordingly, establishment of cell-fate asymmetry often requires protein polarization in ACD progenitor cells5,6.

Stomatal development in Arabidopsis provides a model system for understanding how protein polarization in an ACD progenitor cell results in cell-fate asymmetry in daughter cells. Stomatal development begins with the emergence of a stomatal lineage stem cell, a meristemoid mother cell (MMC), from a subset of protodermal cells (PrCs) located in the epidermis of a developing leaf (Extended Data Fig. 1a, left). The MMC undergoes ACD to yield two asymmetric daughter cells: a smaller meristemoid and a larger stomatal lineage ground cell (SLGC)7. The meristemoid undergoes subsequent rounds of cell division before differentiating into guard cells (GCs), two of which constitute a stomatal pore that facilitates exchange of gas and water vapour between the plant and the environment (Extended Data Fig. 1a, right). The SLGC, in contrast to the meristemoid, has a limited ability to divide and typically differentiates into a non-stomatal pavement cell (PC), which provides protection and structural support for other cell types in the leaf. Stomatal division and cell-fate differentiation can be responsive to external cues, thus enabling plants to optimize the number and distribution of stomatal pores in response to environmental or developmental changes8–10.

Emergence of an ACD progenitor cell (a MMC) from a PrC depends on the activity of the transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH)11, which controls the expression of genes that function in stomatal lineage cell division and stomatal formation12. SPCH regulates stomatal ACD, at least in part, by activating the expression of the scaffold protein BREAKING OF ASYMMETRY IN THE STOMATAL LINEAGE (BASL)12. In the MMC, BASL polarizes at the cell membrane (Extended Data Fig. 1a, dashed box) to establish cellular asymmetry that ultimately leads to division-plane asymmetry13. Polarized BASL together with other scaffold protein families, POLAR14 and BRX15, provide a platform for the assembly of a polarity complex that is maintained during MMC division and inherited by the SLGC daughter cell (Extended Data Fig. 1a).

During the progression of stomatal ACD, changes in the composition of the polarity complex facilitate cell-fate asymmetry by modulating the activity of SPCH (Extended Data Fig. 1a, dashed box)16. In the MMC, the polarity complex contains the MAPKK kinase YODA (YDA)17,18 and the GSK3-like BIN2 kinases19, which function as negative and positive regulators of SPCH, respectively20–22 (Extended Data Fig. 1a, left dashed box). YDA inhibits SPCH by stimulating a MAPK signalling cascade that results in the degradation of SPCH in the nucleus20. In contrast, the association of BIN2 with the polarity complex inhibits YDA22. Hence, at the membrane, BIN2 functions as a de facto activator of SPCH by inhibiting its degradation19,22. Therefore, in the MMC before ACD, the association of BIN2 with the polarity complex enables the activity of SPCH to promote cell division19. In the differentiated daughter cell (the SLGC), BIN2 is repartitioned to the nucleus, which relieves the BIN2-dependent inhibition of YDA and results in the degradation of SPCH (Extended Data Fig. 1a, right dashed box)19. Therefore, in the SLGC, the repartitioning of BIN2 to the nucleus suppresses cell division. Accordingly, differences between the composition of the polarity complex in the MMC versus in the SLGC alter the cell-division potential and fate specification of these cell types16. Nevertheless, the mechanistic basis for the changes in the composition of the polarity complex that are essential for cell-fate asymmetry in stomatal ACD has not been defined.

Results

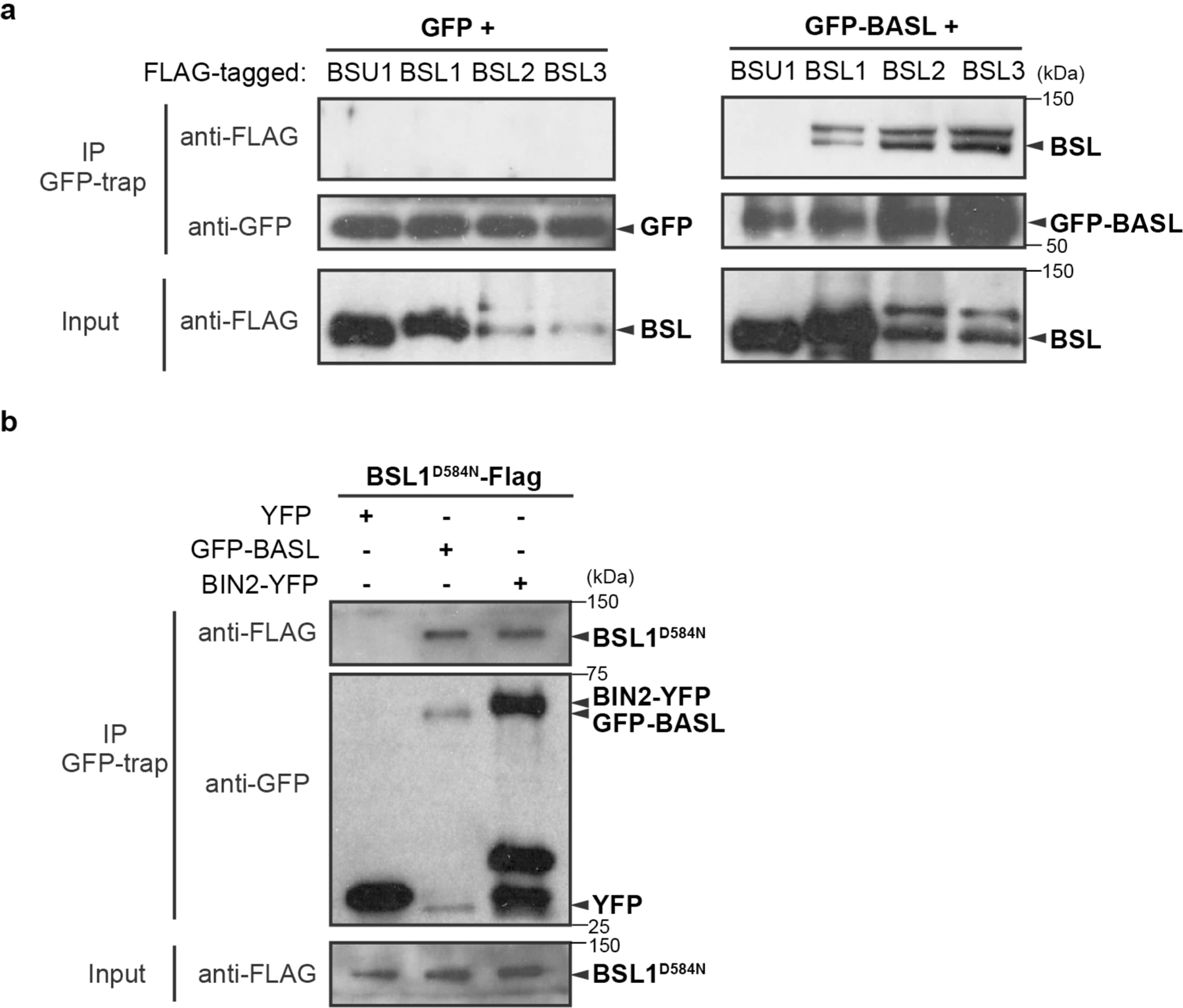

BSL protein phosphatases interact with BASL.

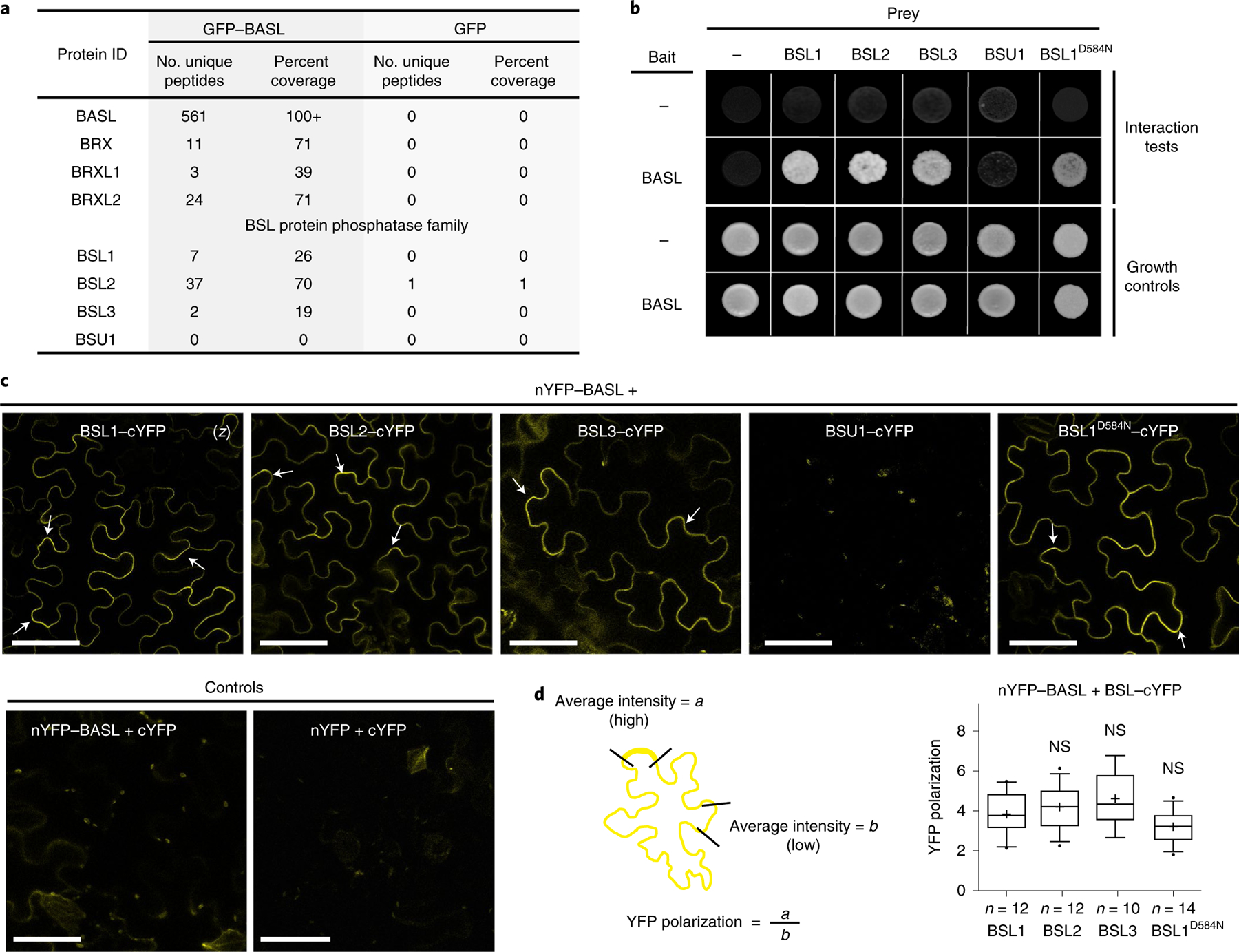

We hypothesized that the repartitioning of BIN2 to the nucleus is driven by one or more factors that associate with the polarity complex. Therefore, we used an unbiased biochemical approach to isolate proteins in Arabidopsis cell extracts that associate with the polarity complex by interacting with BASL (Fig. 1a). We expressed a fusion of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and BASL (GFP–BASL; driven by the endogenous promoter or by the ubiquitous 35S promoter13) or GFP alone (driven by the BASL promoter) in Arabidopsis and used mass spectrometry (MS) to identify candidate BASL-interacting proteins as those recovered by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) with GFP–BASL but not GFP (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1). We identified several proteins previously shown to associate with the polarity complex, including the BRX proteins15 (Fig. 1a), thus validating this approach. We also identified several proteins not previously shown to associate with the polarity complex, including several members of the BSL family of Ser/Thr protein phosphatases (BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3; Fig. 1a). BSL proteins were of particular interest because they have previously been shown to modulate the activity of BIN2 in plant responses to the phytohormone brassinosteroids (BRs)23 (Extended Data Fig. 1b, right). To confirm that BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3 interact with BASL, we performed pairwise yeast two-hybrid assays and in vitro co-IP assays using purified fusion proteins produced by Nicotiana benthamiana leaf cells. The results established that BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3 directly interact with BASL, whereas we did not detect interactions between BASL and the fourth BSL protein BSU1 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2a). In addition, mutating the putative phosphatase active site of BSL1 (BSL1D584N)24 did not affect the interaction with BASL in yeast two-hybrid or pull-down assays (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 2b). Taken together, these results identify BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3 as previously unknown BASL-interacting proteins.

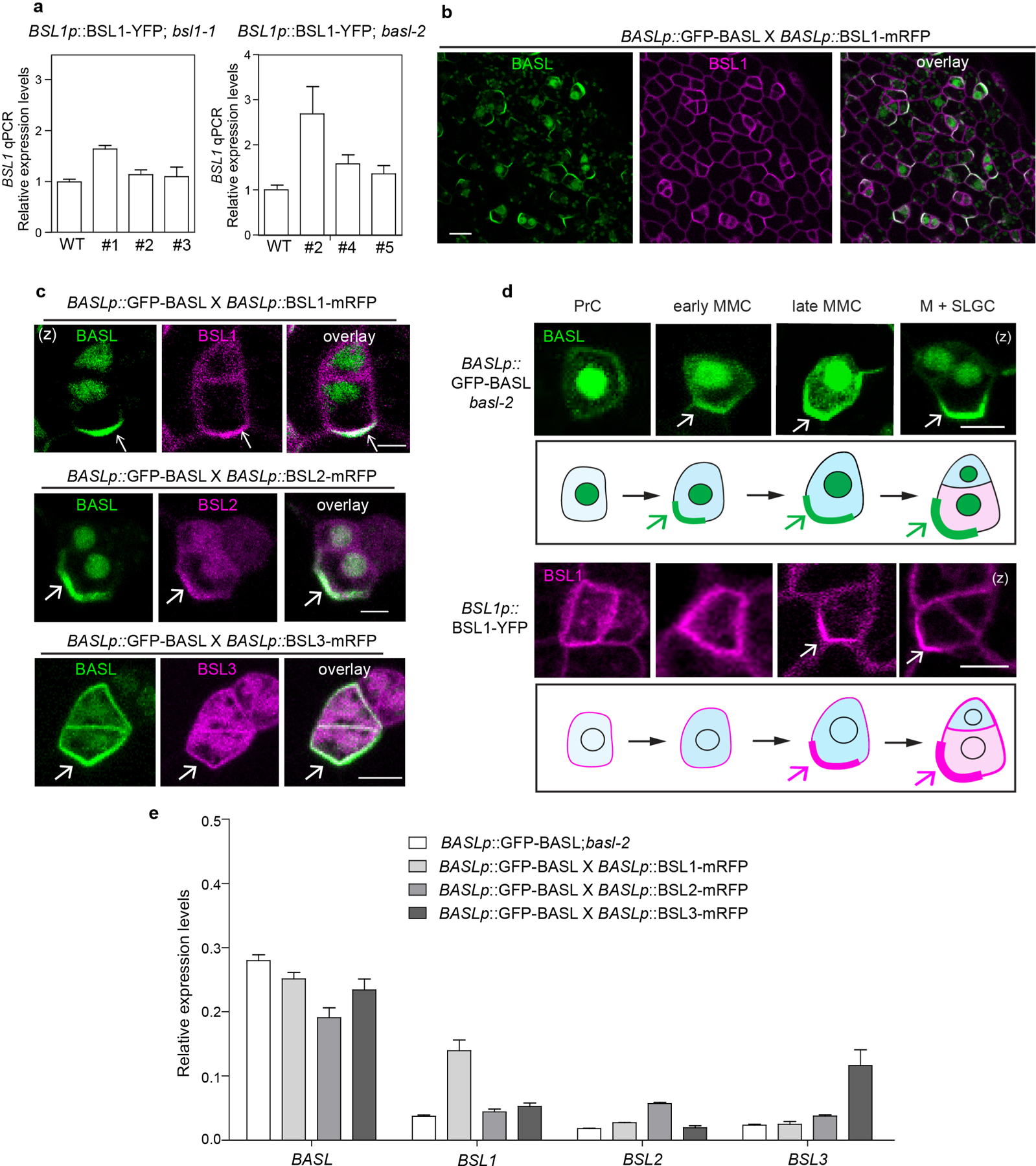

Fig. 1 |. Identification of BSL proteins as putative physical partners of the polarity protein BASL.

a, Identification of BASL-interacting proteins in Arabidopsis using co-IP coupled with MS. Total cell protein from Arabidopsis seedlings expressing GFP–BASL (35Sp::GFP–BASL or BASLp::GFP–BASL;basl-2) were extracted and applied to GFP-Trap agarose beads. Eluted proteins were sent for MS analysis to identify possible interacting proteins. Seedlings expressing GFP alone (BASLp::GFP) were assayed in parallel as control. Detailed MS data can be found in Supplementary Table 1. b, Results of yeast two-hybrid assays showing that BSL proteins directly interact with BASL. For the bait column, the dash indicates the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (BD) while BASL indicates the BD–BASL fusion protein. For the prey row, the dash indicates the Gal4 activation domain (AD) while BSL1, BSL2, BSL3, BSU1 and BSL1D584N indicate BSL–AD protein fusions. Interaction tests indicate assays performed using synthetic dropout medium (-Leu-Trp-His; 1 mM 3-AT added to suppress bait autoactivation), and growth controls indicate assays performed using rich media (-Leu-Trp). c, Results of BiFC assays in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells showing that BSL proteins interact with BASL in a polarized manner along the cell periphery (arrows). YFP signals indicate protein–protein interactions. (z), all images are z-stacked confocal images. Scale bar, 50 μm. d, Left: graphic of the method for the quantification of YFP polarization in the BiFC assays. Right: quantification of polarized BASL–BSL interactions. Confocal images were captured using same settings, and z-stacked images were measured to obtain values of absolute fluorescence intensity. Same lengths were selected for a (high fluorescence) or b (low fluorescence), and average intensity values were taken to obtain the ratios of a/b (values > 1 indicate positive polarization). Box plots show the first and third quartiles, split by the median (line) and mean (cross). Two-sided t-test; n, number of cells. NS, not significant.

To determine where BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3 interact with BASL in plant cells, we performed bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1). The BiFC assay relies on the ability of non-fluorescent fragments of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP; amino-terminal YFP (nYFP) and carboxy-terminal YFP (cYFP)) to complement one other when brought within close proximity. Thus, we monitored the fluorescent signal observed in cells in which nYFP-tagged BASL was co-expressed with cYFP-tagged BSL. Analysis of the subcellular localization of full-length YFP-tagged proteins indicated that when individually expressed in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cell, BASL, BSL2 and BSL3 are distributed in the cytoplasm and nucleus. Meanwhile BSL1 is predominant in the cytoplasm close to the cell cortex and BSU1 is predominant in the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Strikingly, in cells co-expressing nYFP–BASL and cYFP-tagged BSL1, BSL2, BSL3 or BSL1D584N, we observed a strong fluorescent signal associated with the cell periphery but no signal in the nucleus (Fig. 1c). More interestingly, the BASL–BSL interaction signals showed an uneven distribution (Fig. 1c,d). Such BiFC signal polarization was also identified when BASL was co-expressed with other physical partners, such as YDA or BIN2, in N. benthamiana cells18,19. In contrast, no fluorescence was detected in plant cells co-expressing nYFP–BASL and BSU1–cYFP or in the control experiments (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Thus, the results of the BiFC assays indicate that interactions between BASL and BSL1, BSL2 or BSL3 proteins stabilize the association of these factors at the cell cortex and promote protein polarization in plants.

BSL proteins colocalize with polarized BASL in stomatal lineage cells.

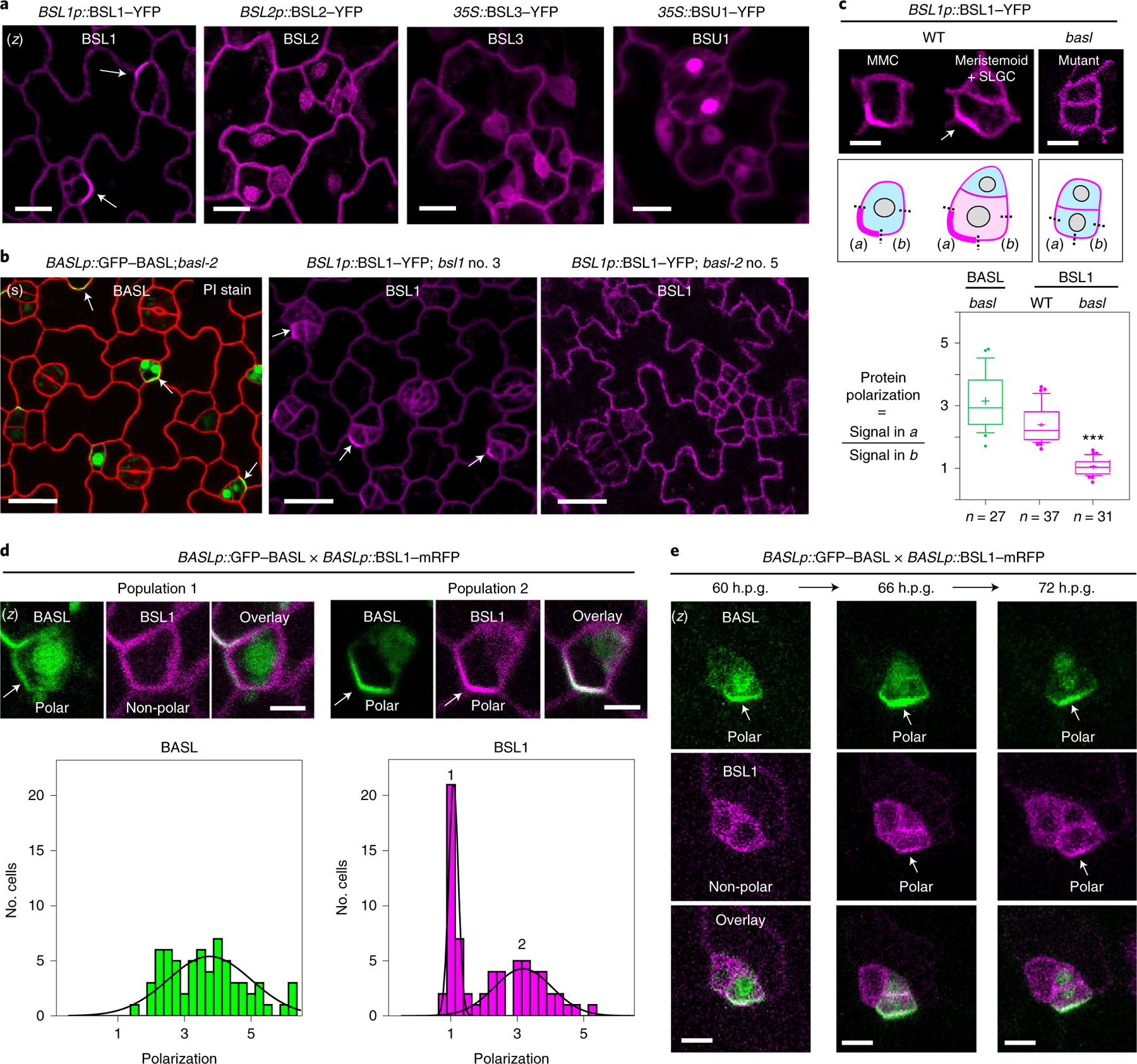

To establish whether BSL proteins interact with BASL at the cell periphery in stomatal lineage cells, we monitored the subcellular localization of BSL–YFP fusion proteins, the expression of which was driven by either the endogenous promoter or the ubiquitous 35S promoter in Arabidopsis leaf epidermal cells. Across all cell types, BSL1 was predominantly located in the cytoplasm close to the cell periphery, while BSL2 and BSL3 were located in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, in the subset of epidermal cells that constitute the stomatal lineage, BSL1 polarized at the cell periphery (Fig. 2b and Extended Data Fig. 3a) and exhibited a localization pattern that bears a strong resemblance to the localization pattern observed for polarized BASL (Fig. 2b, left). However, differing from BASL, BSL1 does not localize to the nucleus where BASL is initially stored18. To directly determine whether BSL1 colocalizes with polarized BASL in stomatal lineage cells, we monitored protein localization in plants co-expressing GFP–BASL and BSL1–monomeric red fluorescent protein (BSL1–mRFP) (Extended Data Fig. 3b). The results definitively showed that BSL1 and BASL colocalize and polarize together at the cell periphery in stomatal lineage cells (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). While the expression of BSL2–YFP or BSL3–YFP alone did not exhibit discernible polarization at the expression levels analysed, analysis of protein localization in plants co-expressing GFP–BASL and BSL2–mRFP or BSL3–mRFP showed that BSL2 and BSL3 also colocalized with BASL and were enriched at the cell periphery where BASL is polarized in stomatal lineage cells (Extended Data Fig. 3c,e). Thus, we conclude that BSL proteins, in particular BSL1, colocalize with polarized BASL at the cell periphery in Arabidopsis stomatal lineage cells.

Fig. 2 |. Polarization of BSL1 requires BASL in Arabidopsis.

a, Subcellular localization of the BSL proteins (magenta) in stomatal lineage cells in 3-d.p.g. Arabidopsis adaxial cotyledon epidermis. Note that BSL1 is mainly cytoplasmic, close to the cell periphery and polarized (arrow), whereas BSL2, BSL3 and BSU1 are cytoplasmic and nuclear. Scale bar, 10 μm. b, Confocal images showing polarization of BASL (green) and BSL1 (magenta) in stomatal lineage cells (arrows) and the absence of BSL1 polarization in the null basl-2 cells. Images show cells expressing BASLp::GFP–BASL in basl-2 (green, left), BSL1p::BSL1–YFP in bsl1–1 (magenta, middle) and BSL1p::BSL1–YFP in basl-2 (magenta, right) Red, PI staining. (s), single optical sections. Scale bar, 20 μm. c, Quantification of native-promoter-driven BSL1 polarization in wild-type (WT) versus basl-2 plants. Top, representative images and quantification method of BSL1 localization in different backgrounds (magenta). Scale bar, 2 μm. Polarization was calculated as the ratio of the fluorescence in segment a versus b. Bottom, quantitation of BSL1 polarization. Box plot shows first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). Data were analysed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. n, number of stomatal lineage cells. ***P < 0.0001. d, Differential polarization of BASL and BSL1 (arrows) in MMCs. Top, representative images of cells in indicated populations of MMCs containing BSL1–mRFP (magenta) and GFP–BASL (green). Scale bar, 2 μm. Bottom, histograms of polarization values for BASL and BSL1. The two curves correspond to the two populations demonstrated above. n = 68 cell co-expressing GFP–BASL and BSL1–mRFP, both driven by the BASL promoter, in a true leaf of a 5-d.p.g. seedling. e, Time-course confocal images showing the differential polarization timing of GFP–BASL (green) and BSL1– mRFP (magenta) at three successive intervals of time during an ACD. Left, before ACD; middle, during ACD; and right, after ACD. (z), images are z-stacked. Scale bar, 5 μm.

The polarization of BSL1 requires BASL during stomatal ACD.

As BSL1 is evidently polarized in stomatal lineage cells, we tested whether BSL polarization requires BASL by using BSL1 as a representative member. We monitored the localization of native-promoter-driven BSL1–YFP in loss-of-function bsl1 plants, in wild-type plants or in plants containing a loss-of-function basl-2 allele (Fig. 2b,c). To measure protein polarization, for each cell containing detectable levels of BSL1–YFP or GFP–BASL, we calculated the ratio of YFP/GFP fluorescence at the polarity crescent (Fig. 2c, box (i)) relative to the fluorescence observed in a segment of the cell membrane adjacent to the polarity crescent and with the same length (Fig. 2c, box (ii)). Thus, a polarization value of ~1 indicates that BSL1/BASL is not polarized while a polarization value of >1 indicates BSL1/BASL polarization. The results in Fig. 2c show that BSL1 polarization occurs in stomatal lineage cells from wild-type plants (mean = 2.3, s.d. = 0.6, n = 37) but does not occur in cells from basl-2 plants (mean = 1.0, s.d. = 0.2, n = 31). Thus, BSL1 polarization requires BASL in stomatal lineage cells.

Taken together, the results in Fig. 2 establish that BSL proteins may polarize in cells, at least in part, by directly interacting with the BASL scaffold protein. Thus, BSL proteins, in particular BSL1, exhibit the defining hallmark of polarity-complex-associated factors. Accordingly, we conclude that BSL proteins associate with the polarity complex that is required in stomatal lineage cells.

The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex occurs in MMCs at the onset of mitosis.

Unexpectedly, in an analysis of MMCs in plants co-expressing GFP–BASL and BSL1–mRFP, we observed two populations of cells: one in which only GFP–BASL was polarized and another in which both GFP–BASL and BSL1–mRFP were polarized (Fig. 2d and Extended Data Fig. 3d). Thus, BASL polarization is necessary but not sufficient for BSL1 polarization. The differences in the size and shape of cells constituting each population raises the possibility that BSL1 polarization occurs at a later time in development than BASL polarization (Fig. 2d). To demonstrate this, we performed time-lapse analysis of stomatal lineage cells expressing both GFP–BASL and BSL1–mRFP. Examination of protein localization at 60 h post-germination (60 h.p.g.) identified cells exhibiting polarized BASL, whereas BSL1 polarization was below detection levels (Fig. 2e, left). Later (66 h.p.g.), when the cell undergoes mitosis, BSL1 polarization became more evident and overlapped with polarized BASL (Fig. 2e, middle). After ACD, polarization of both proteins remained visible in the SLGC (72 h.p.g.) (Fig. 2e, right). Thus, our results of the time-lapse experiments clearly demonstrate that BSL1 becomes polarized after BASL polarization.

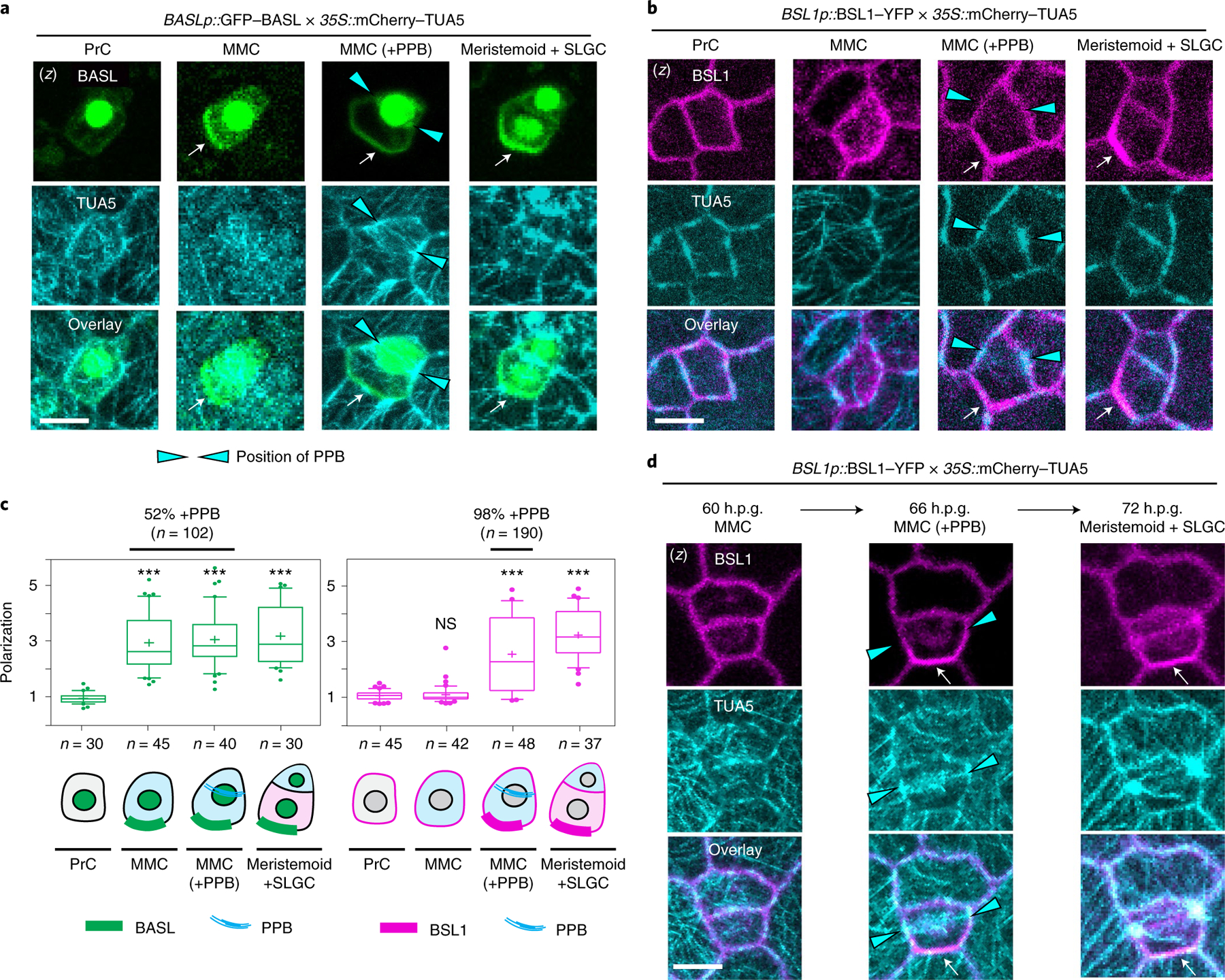

To further determine the timing of BASL polarization relative to BSL1 polarization, we took advantage of our ability to identify the subset of MMCs committed to cell division using the microtubule marker mCherry–TUA5 (ref. 25), which enables visualization of the pre-prophase band (PPB) that forms at the onset of mitosis26(Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). We used the mCherry–TUA5 marker to monitor the progression of the cell cycle in MMCs containing polarized GFP–BASL or polarized BSL1–YFP, the expression of which were driven by the respective native promoter (Fig. 3a–c). The results indicated that PPB formation occurred within half of the MMCs containing polarized BASL (~52%, n = 102) but within nearly all of the MMCs containing polarized BSL1 (~98%, n = 190) (Fig. 3c). These results establish that BASL polarization, but not BSL1 polarization, can occur before the entry of the MMC to cell division. Thus, BASL polarization occurs at an earlier developmental time point than BSL polarization.

Fig. 3 |. The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex occurs in MMCs at the entry of mitosis.

a,b, BSL1 polarization coincides with the formation of the PPB. Images show the co-expression of BASLp::GFP–BASL (a, green) or BSL1p::BSL1–YFP (b, magenta) with the ubiquitous 35S-promoter-driven microtubule marker mCherry–TUA5 (cyan) in consecutive cell types (PrC, MMC, MMC with PPB and SLGC) during stomatal ACD. The expression of mCherry–TUA5 allows visualization of the formation of the PPB (cyan arrowheads) during mitosis. Arrows indicate protein polarization. Scale bar, 5 μm. c, Quantification of protein polarization of BASL (left) and BSL1 (right) in successive cell types shown in a and b. Values > 1 indicate positive polarization. Box plots show first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests were performed to compare the values for designated cell type with the values for the PrC. n, number of cells counted. ***P < 0.0001. The percentage indicates the MMCs containing PPB among the MMCs exhibiting polarized BASL or BSL1 (n, number MMCs with polarized BASL or BSL1). d, Time-lapse images showing that BSL1 polarization (magenta) coincides with PPB formation (cyan arrowheads) during an ACD. Left, before ACD; middle, during ACD; right, after ACD. Arrows indicate protein polarization. Scale, 5 μm. (z), z-stacked confocal images in a, b and d.

Next, to examine the timing of BSL1 polarization relative to PPB formation, we selected MMCs containing the PPB and determined the percentage of these in which BSL1 was polarized. The results showed that ~98% of MMCs containing the PPB also contain polarized BSL1 (n = 146). Thus, we observed a nearly one-to-one correspondence between the presence of the PPB and the presence of polarized BSL1 in MMCs. Furthermore, time-lapse examination of stomatal lineage cells expressing both BSL1–YFP and mCherry–TUA5 demonstrated the co-occurrence of BSL1 polarization and the formation of the PPB during stomatal ACD (Fig. 3d, 66 h.p.g.). Thus, these results suggest that BSL1 polarization occurs at the same time in development as PPB formation. Accordingly, we conclude that the association of BSL1 with the polarity complex occurs when MMCs enter cell division.

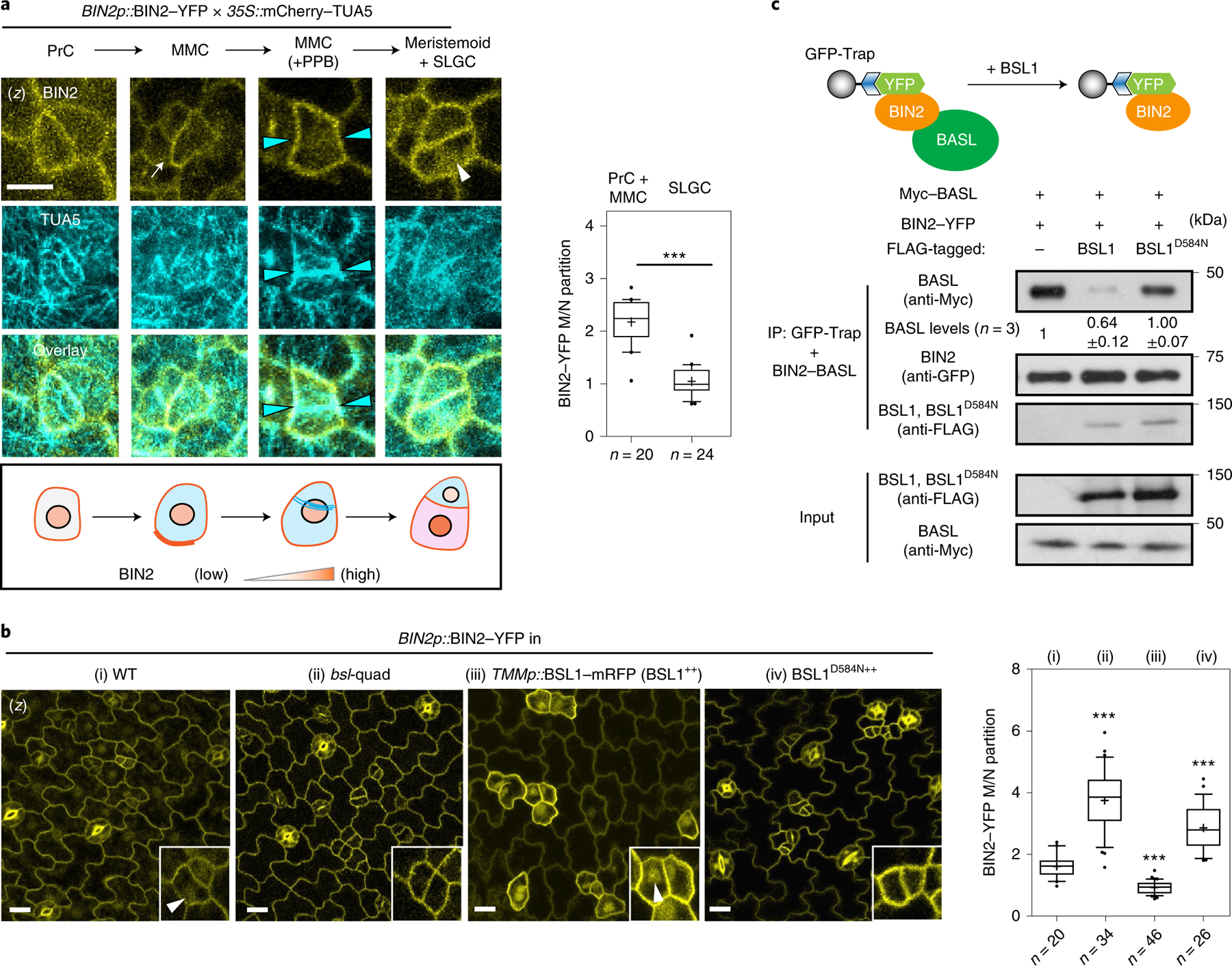

The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex promotes BIN2 partitioning to the nucleus.

As mentioned above, the GSK3-like BIN2 kinases associate with the polarity complex to promote MMC division19,22. After ACD, repartitioning of BIN2 to the nucleus enables suppression of SPCH and inhibition of cell division in the SLGC (Extended Data Fig. 1b, left). Because BSL1 polarization occurs at the entry of MMC division, we investigated whether BSL proteins function in the repartitioning of BIN2. First, we checked the nuclear partitioning of BIN2 before and after PPB formation. We imaged stomatal lineage cells co-expressing BIN2–YFP with mCherry–TUA5 and quantified the membrane/nuclear partitioning of BIN2 in pre-divisional cells (PrCs and MMCs) compared with post-divisional cells (SLGCs) (Fig. 4a). The results showed that BIN2 is predominantly associated with the membrane of PrCs and MMCs, whereas it preferentially partitioned in the nucleus of SLGCs (Fig. 4a, right). Thus, these results demonstrate that the changes in BIN2 nuclear partitioning occur between the MMC and the SLGC, during which polarization of BSL1 occurs.

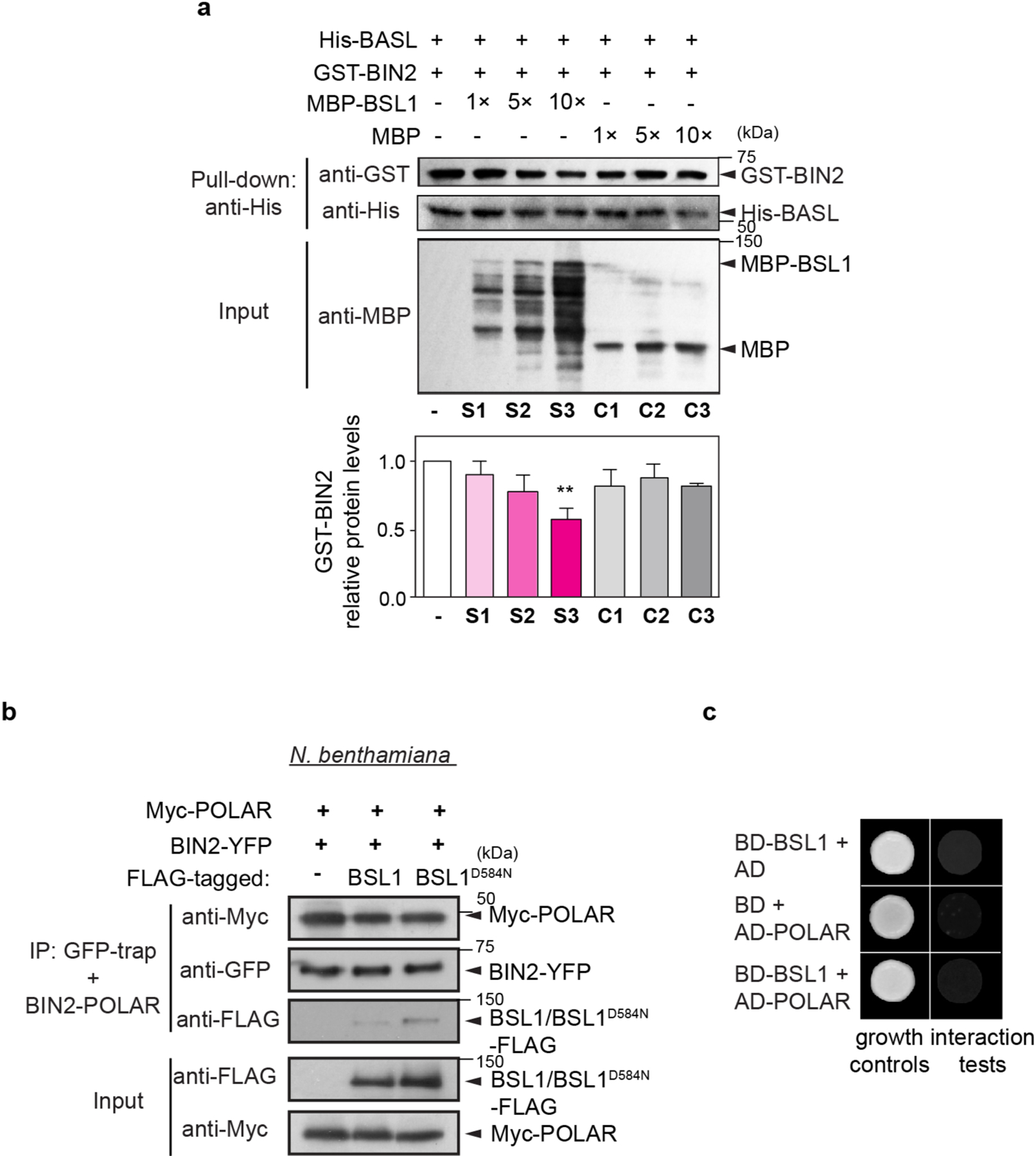

Fig. 4 |. The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex promotes BIN2 partitioning to the nucleus.

a, Left: representative confocal images showing changes in BIN2 membrane/nucleus (M/N) partitioning in consecutive stomatal lineage cells co-expressing BIN2p::BIN2–YFP (yellow) and 35Sp::mCherry– TUA5 (cyan). Arrows indicate preferential membrane localization and polarization of BIN2 in the MMC. White arrowhead indicates preferential nuclear localization of BIN2 in the SLGC. Cyan arrowheads indicate the position of the PPB. The cartoon depicts the corresponding protein localization of BIN2 (orange) at each stage shown above. Scale bar, 5 μm. Right: quantification of the membrane/nuclear (M/N) partition of BIN2–YFP in pre-divisional cells (PrC or MMC) versus that in post-divisional SLGCs. Box plots show the first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). Two-tailed Student’s t-test. n, number of cells. ***P < 0.0001. b, Left, representative confocal images showing the expression patterns of BIN2p::BIN2–YFP (yellow) in indicated genetic backgrounds. bsl-quad, quadruple loss-of-function mutant; BSL1++ or BSL1D584N++, plants overexpressing BSL1 or phosphatase-dead BSL1D584N (both driven by the stomata lineage TMM promoter; elevated transcript levels shown in Extended Data Fig. 4a). Inset, enlarged views show the subcellular partitioning of BIN2. Arrowheads indicate the preferential nuclear localization of BIN2. Scale bar, 10 μm. Right, quantification of M/N partitioning of BIN2– YFP. Absolute fluorescence intensity values from the membrane or nuclear regions of a cell were taken. All images were captured with same settings and z-stacked for measurement. Box plots show the first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc tests were performed to compare with the WT. n, number of cells. ***P < 0.0001. c, BSL1 but not BSL1D584N interferes with the interaction of BIN2 with BASL. Top, schematic of the co-IP assay used to monitor the ability of BSL1/BSL1D584N–FLAG to affect the interaction between BIN2–YFP and Myc–BASL. Bottom, results were detected by western blotting. Specifically, the designated protein fusions were overexpressed and purified from N. benthamiana leaf cells. BIN2–YFP and Myc–BASL were co-expressed in the presence or absence of BSL1/BSL1D584N–FLAG. The interactions of BIN2–BASL were assayed by the amount of Myc–BASL being immunoprecipitated by BIN2–YFP bound to GFP-Trap agarose beads. Quantification of the amount of BASL interacting with BIN2 is shown as the mean ± s.d., n = three biological replicates.

To measure the ability of BSL proteins to modulate BIN2 repartitioning in stomatal lineage cells, we analysed the distribution of BIN2–YFP in wild-type plants, in plants lacking all four BSL proteins (bsl-quad)22 and in plants in which BSL1 is overexpressed (BSL1++, whereby BSL1–mRFP expression is driven by the stomatal lineage Too Many Mouths promoter27) (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 4a–c). Interestingly, we observed a substantial decrease in the proportion of BIN2 in the nucleus in plants lacking BSL, whereas we observed a substantial increase in the proportion of BIN2 in the nucleus in plants in which BSL1 is overexpressed (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 4b,c). These results establish that BSL proteins modulate the partitioning of BIN2 between the nucleus and cell membrane in stomatal lineage cells.

Our finding that BSL1 itself associates with the polarity complex (Fig. 1) raises the possibility that BSL1 may modulates BIN2 partitioning by (1) its phosphatase activity and/or (2) displacing BIN2 from binding its partners in the polarity complex. To test whether phosphatase activity is required for BSL1 regulation, we examined BIN2 localization in stomatal lineage cells overexpressing the catalytically inactive BSL1D584N. In contrast to the native form, this putative phosphatase-dead version failed to induce the nuclear partitioning of BIN2 (Fig. 4b), which indicates that BSL1 relies on its phosphatase activity to regulate BIN2 localization.

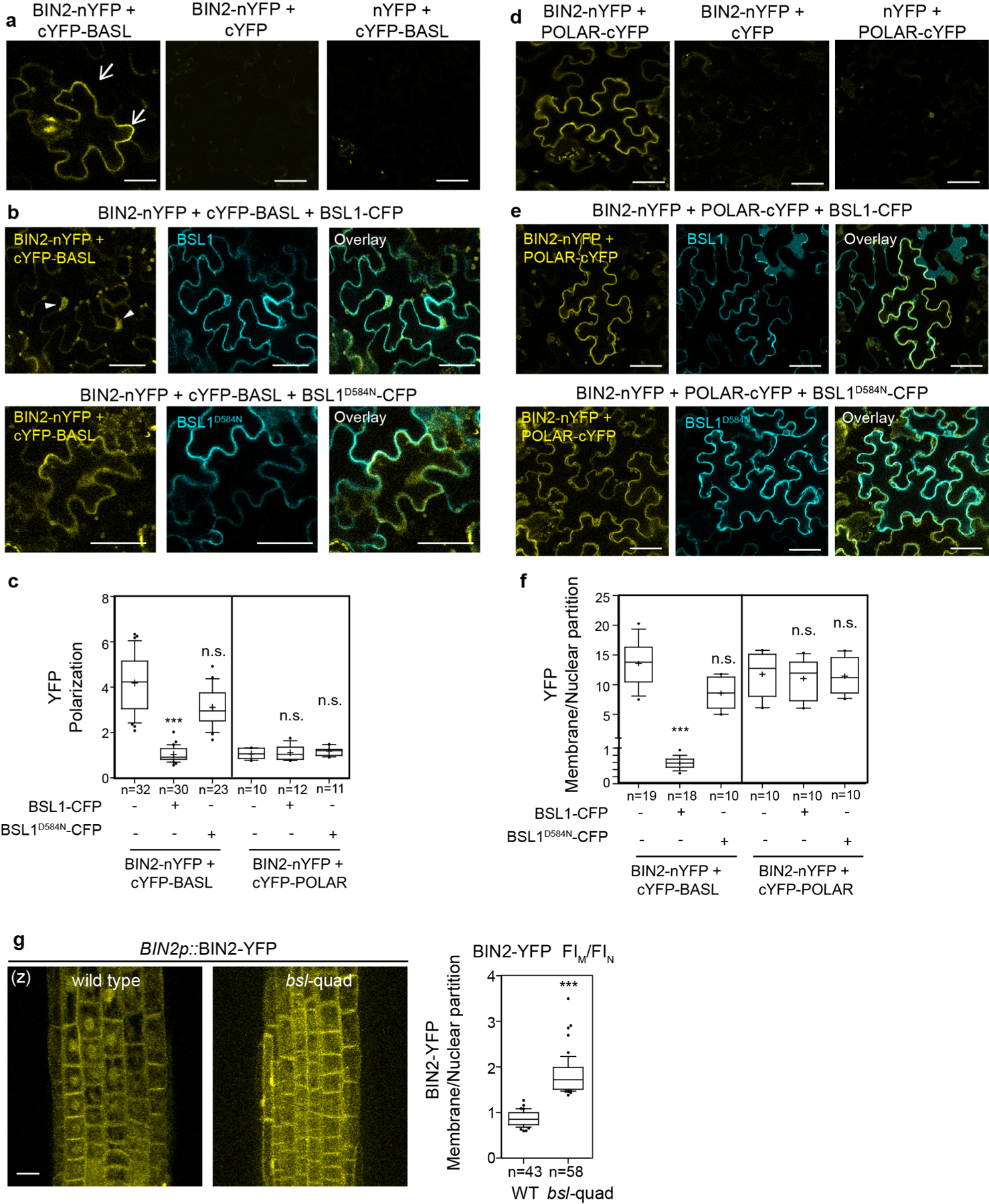

The association of BIN2 with the polarity complex mainly relies on interactions with the scaffold POLAR proteins, and BIN2 also interacts with BASL19. POLAR and BASL belong to the same polarity complex, but polarization of POLAR in stomatal lineage cells is BASL-dependent14. We analysed the ability of BSL1 to affect the interaction of BIN2–BASL in vitro and in planta (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 5a). The co-IP experiments using overexpressed proteins purified from N. benthamiana leaves showed that the BIN2–BASL interaction is significantly reduced in the presence of BSL1 (Fig. 4c). Also, in the in vitro competitive pull-down assays, gradually increasing the amount of BSL1 protein lowered the amount of BIN2 bound to BASL (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Next, the ability of BSL1 to interfere in the BIN2–BASL interaction was further confirmed in planta using BiFC assays (Extended Data Fig. 6a–c). These results show that when BSL1 is co-expressed, the polarized BiFC signal of the BIN2–BASL interaction at the cell periphery becomes less polarized and preferentially partitioned to the nuclei of N. benthamiana epidermal cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c,f). Furthermore, consistent with data in Arabidopsis (Fig. 4b), the activity of BSL1 in interfering with the BIN2–BASL interaction depends on the catalytic site of this phosphatase (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 6b,c,f). Thus, these results indicate that BSL1 affects the BIN2–BASL interaction both in vitro and at the cell membrane in plants. Furthermore, the ability of BSL1 to interfere with the BIN2–BASL interaction appears to be specific, as BSL1 does not affect the interaction between BIN2 and the scaffold protein POLAR in both co-IP and BiFC assays (Extended Data Figs. 5b and 6d–f).

Last, we assayed whether the BSL1-mediated regulation of BIN2 nuclear partitioning depends on the polarity scaffold protein BASL. In root epidermal cells, where no expression of BASL is detected13 (also based on the eFP database28), BIN2 partitioning to the nucleus was significant less in a bsl-quad mutant (Extended Data Fig. 6g), which indicates that BASL is not required for BSL to modulate BIN2 localization. Indeed, the phenotype of BSL1 overexpression was not affected by the loss of BASL (Extended Data Fig. 9b). Thus, we propose that BSL-mediated BIN2 nuclear partitioning in SLGCs involves BSL phosphatase activity. Also, BSL1 may, through direct interactions with BASL, actively displace BIN2 from the polarity complex.

The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex activates YDA MAPK signalling.

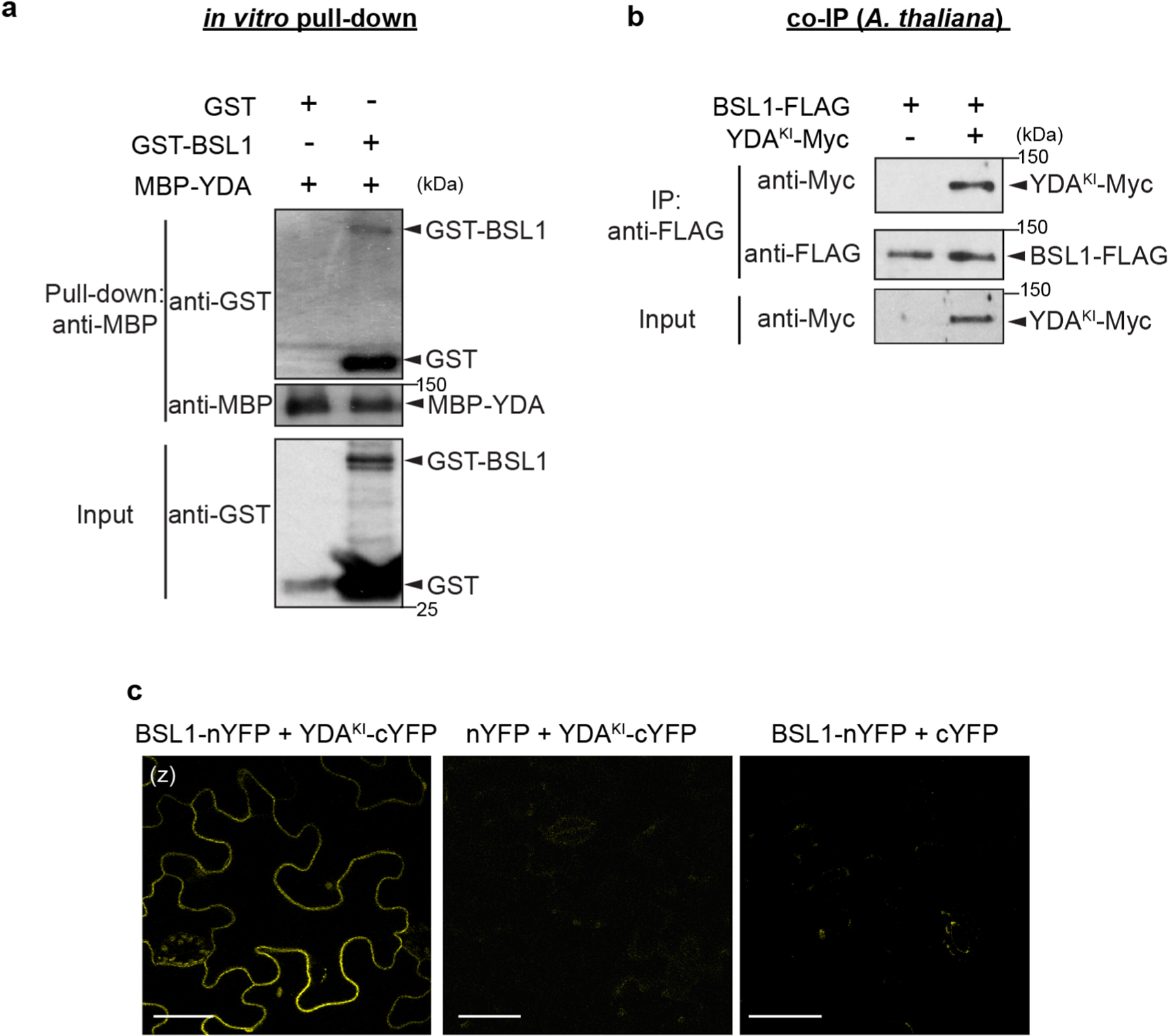

We previously showed that the association of YDA with the polarity complex, like that of BSL proteins, requires interactions with BASL18. The association of both YDA and BSL with the polarity complex through interactions with BASL raises the possibility that YDA and BSL interact with one another. To test this proposal, we measured the ability of BSL1 to interact with YDA both in vitro and in planta (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7a–c). Results of pull-down and co-IP assays performed in vitro using fusion proteins purified from Escherichia coli and from leaf extracts of N. benthamiana, respectively, showed that BSL1 directly interacts with YDA (Fig. 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). Results of BiFC assays showed that BSL1 interacts with YDA at the cell periphery in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Furthermore, results of in vivo co-IP assays analysing the association of fusion proteins co-expressed in Arabidopsis further demonstrated that BSL1 interacts with YDA (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Thus, we conclude that YDA directly interacts with BSL1 both in vitro and in vivo.

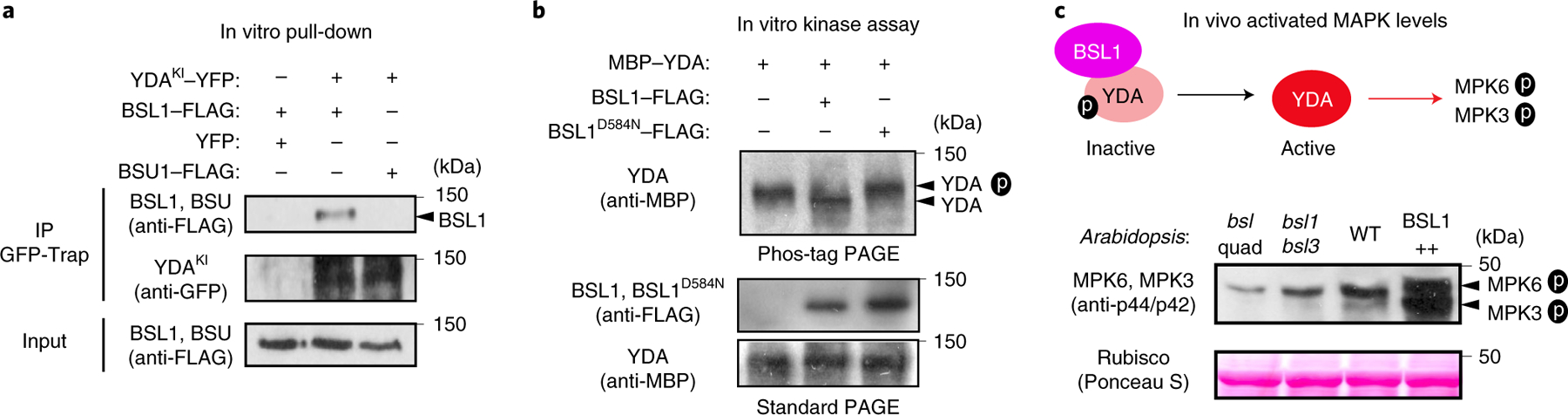

Fig. 5 |. The association of BSL1 with the polarity complex activates YDA and MAPK signalling.

a, In vitro pull-down experiments showing that BSL1 interacts with YDA. BSL1–FLAG and YDAKI–YFP (kinase was made inactive to avoid overexpression-triggered cell death) were overexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves and purified from cell extracts. The BSL1–YDA interaction was assayed by the amount of BSL1 pulled down by YDAKI–YFP bound to GFP-Trap agarose beads. BSU1–FLAG and YFP alone were used as controls. b, In vitro kinase assays showing that BSL1 directly dephosphorylates YDA. Recombinant proteins of MBP–YDA were produced and purified from E. coli cells. BSL1/BSL1D584N–FLAG were produced and purified from N. benthamiana leaf cells. Autophosphorylation of YDA was assayed in the presence and absence of BSL1/BSL1D584N–FLAG, and the phosphorylation levels of YDA were analysed by Phos-tag PAGE. Slow migration indicates that the protein contains more phosphoryl groups. The protein amount used for the assay was visualized by immunoblotting. c, Western blots showing elevated levels of MAPK signalling in vivo. Top: schematic showing that BSL1-mediated dephosphorylation of YDA may activate YDA and promote MAPK signalling in vivo. Bottom: blots showing the phosphorylated MPK3 and MPK6 (activity) levels in 3-d.p.g. Arabidopsis seedlings detected by anti-phospho-p42/p44 (top) and protein loading is shown by Ponceau S staining (bottom). For a–c, results represent three biological replicates.

The activity of YDA is sensitive to its phosphorylation state. In particular, phosphorylation of YDA inhibits its protein kinase activity22. Thus, the ability of BSL protein phosphatases to directly interact with YDA raises the possibility that BSL proteins directly modulate YDA activity by altering its phosphorylation state. To test this proposal, we first monitored the ability of BSL1 to modulate the phosphorylation state of YDA in vitro (Fig. 5b). We incubated the recombinant maltose-binding protein (MBP)–YDA fusion protein with ATP (allowing autophosphorylation) in the presence or absence of BSL1–FLAG and visualized the phosphorylation state of MBP–YDA using Phos-tag gel electrophoresis (Fig. 5b). In reactions containing wild-type BSL1–FLAG, but not the catalytically inactive BSL1D584N, we detected a faster migrating band corresponding to removal of one or more phosphate groups from MBP–YDA (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that BSL1 dephosphorylates YDA in vitro. Next, we measured the ability of BSL proteins to modulate YDA-dependent MAPK signalling in vivo (Fig. 5c). To do this, we monitored the phosphorylation state of two MAPKs (MPK3 and MPK6) whose activities are regulated by YDA in stomatal development29 (Extended Data Fig. 1b, left). Compared with the levels of phosphorylated/activated MPK3 and MPK6 observed in wild-type plants, the levels of phosphorylated/activated MPK3 and MPK6 were reduced in plants lacking BSL1 and BSL3 (bsl1;bsl3) and in plants lacking all four BSL proteins (bsl-quad) (Fig. 5c). In contrast, levels of phosphorylated MPK3 and MPK6 were elevated in plants in which BSL1 is overexpressed (BSL1++) (Fig. 5c). These results indicate that BSL1 stimulates YDA activity in vivo. We conclude that the association of BSL1 with the polarity complex in stomatal lineage cells activates YDA MAPK signalling.

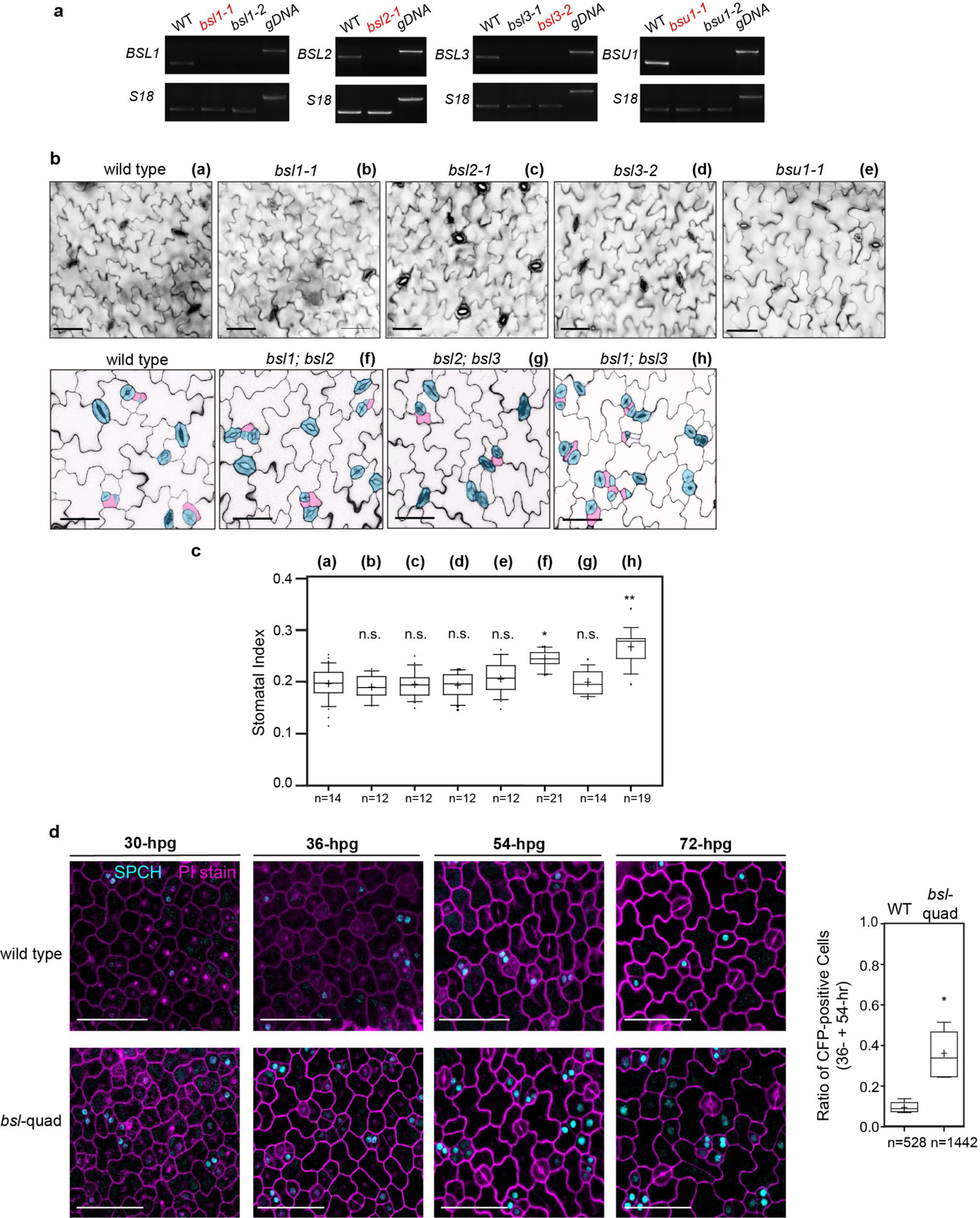

BSL proteins are required for stomatal development in Arabidopsis.

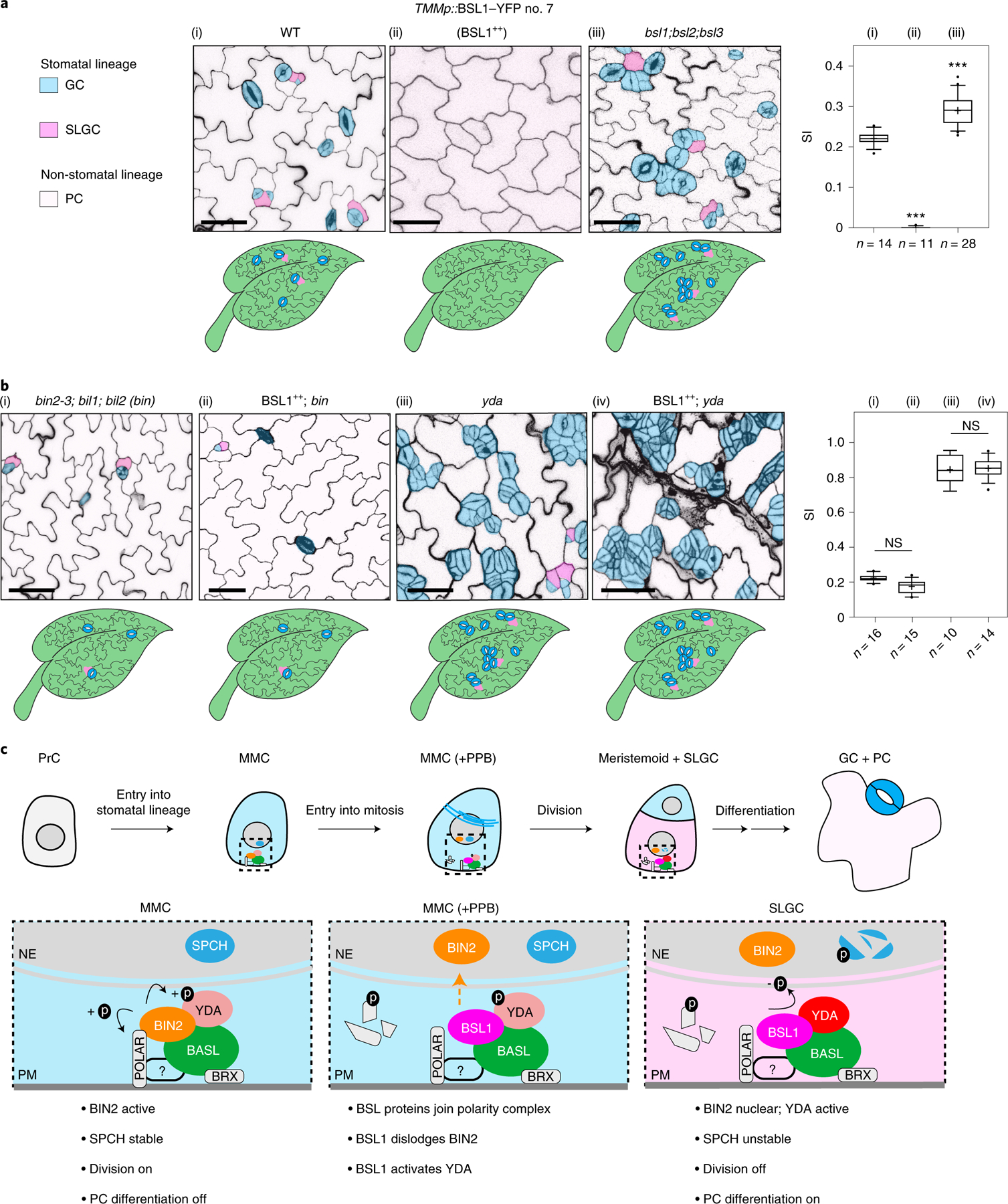

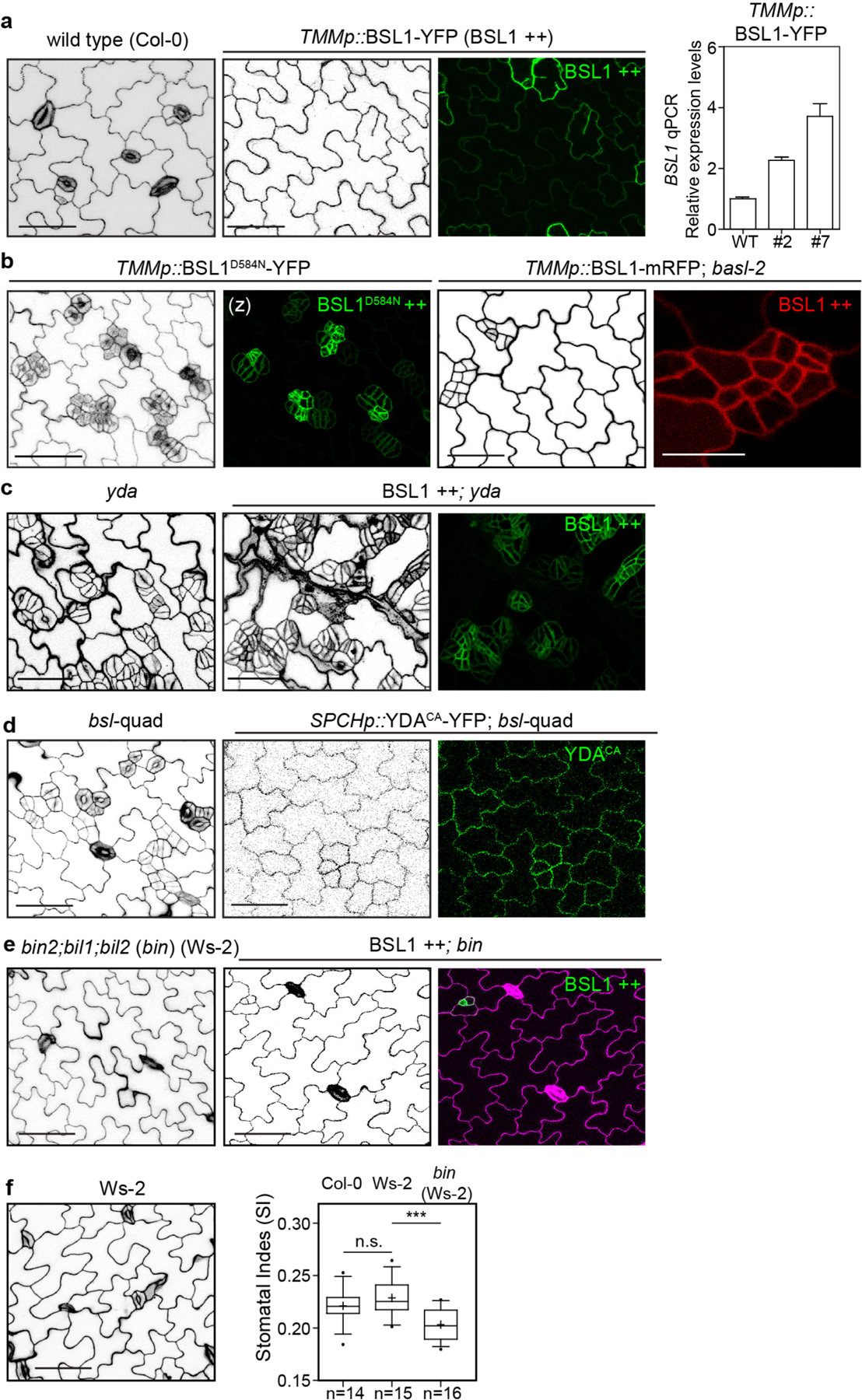

The results in Figs. 1–5 show that BSL proteins, when analysed biochemically and at the cellular level, perform the critical functions required to alter the composition and activity of the polarity complex in the MMC versus the SLGC. Accordingly, the results in Figs. 1–5 strongly suggest that BSL proteins play a key role in establishing cell-fate asymmetry during stomatal ACD in Arabidopsis. To directly test the role of BSL proteins in Arabidopsis stomatal development, we compared the generation of stomatal lineage cells in the epidermis of wild-type plants, in plants in which BSL1 is overexpressed in stomatal lineage cells (BSL1++) and in plants containing loss-of-function bsl alleles (Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 9a). The results showed that overexpression of BSL1 using the stomatal-lineage-specific TMM promoter suppressed the formation of stomatal lineage cells and gave rise to a leaf epidermis fully devoid of GCs (Fig. 6a) even in the absence of BASL (Extended Data Fig. 9b). In contrast, analysis of single, double and triple loss-of-function bsl mutants showed that the absence of BSL proteins leads to an increase in the percentage of stomatal lineage cells compared with wild-type plants (Fig. 6a and Extended Data Fig. 8a–d). These results establish that BSL proteins play a critical role in Arabidopsis stomatal development.

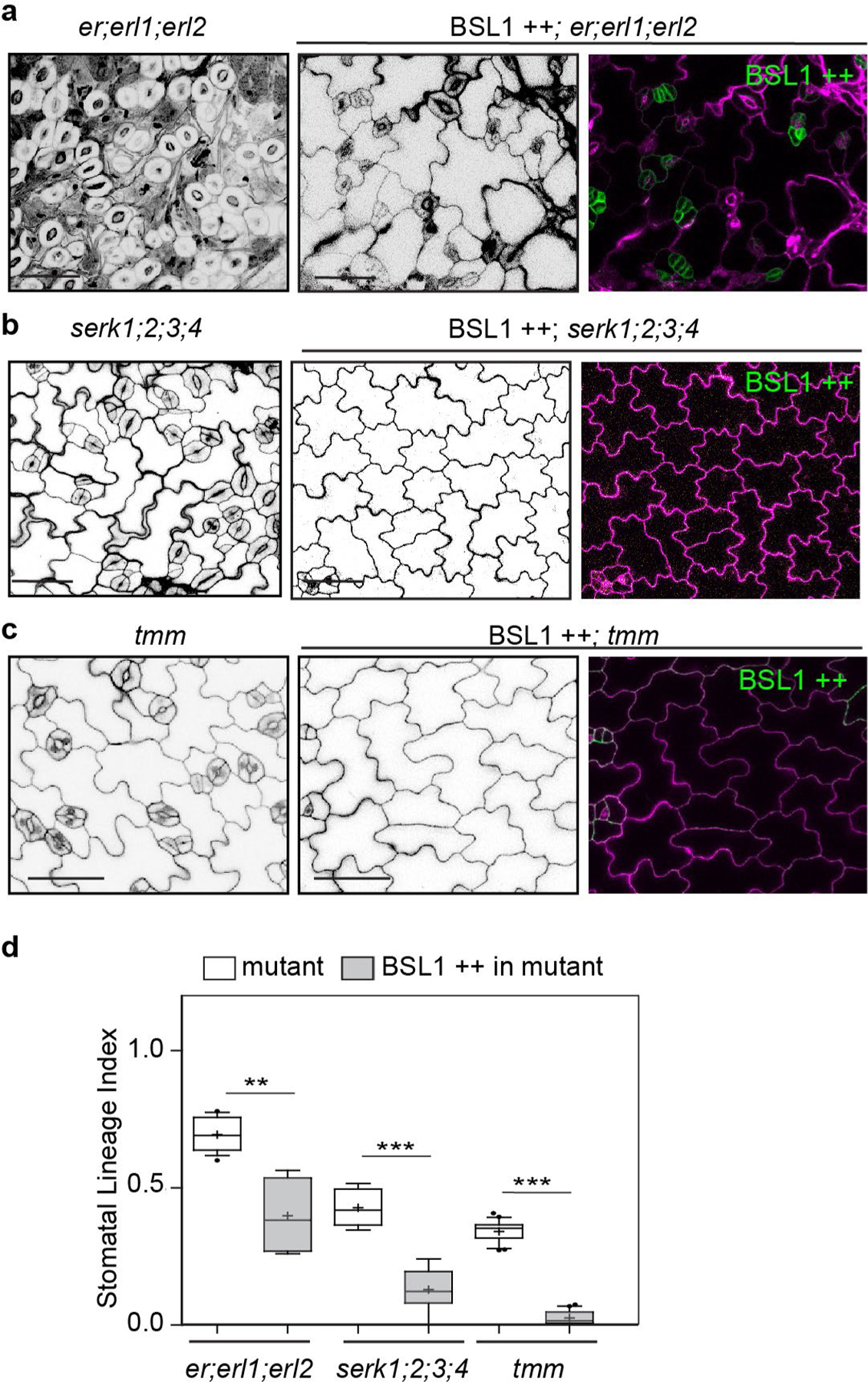

Fig. 6 |. BSL requires BIN2 and YDA to regulate stomatal development in Arabidopsis.

a, BSL proteins function to suppress stomatal production. Left: confocal images (converted to black and white) showing 5-day adaxial cotyledon epidermis of the designated genotypes. BSL1++, overexpression of BSL1 by the stomatal lineage TMM promoter. Stomatal lineage cells were manually traced and highlighted by different shadings. Blue, stomatal GCs; pink, SLGCs; light pink, PCs. Right: quantification of SI (number of stomata relative to the number of total cells). Box plots show the first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). n, number of cotyledons. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test were used to compare with the WT. ***P < 0.0001. b, BSL requires BIN2 and YDA to regulate stomatal development. Confocal images show stomatal phenotypes when overexpression of BSL1 (BSL1++) was introduced in the loss-of-function bin (left) or yda (right) mutants, respectively. Right, quantification of SI of the designated genotypes. Box plots show the first and third quartiles, median (line) and mean (cross). n, number of cotyledons. Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to compare with the respective mutant background. Scale bar, 40 μm (a and b). The cartoons in a and b depict the corresponding stomatal phenotype shown above. Blue, stomatal GCs; pink, stomatal lineage cells; puzzle shapes, PCs. c, Working model whereby BSL proteins function as a spatiotemporal molecular switch enabling stomatal ACD. In the MMC, the high cell division potential is maintained by the BIN2 GSK3-like kinases that associate with the BASL polarity complex via POLAR to be enriched at the cell membrane19, where BIN2 suppresses the MAPKK kinase YDA and MAPK signalling22. Therefore, SPCH activity is maintained at high levels to promote cell division. In this study, we identified the association of the BSL proteins with the BASL polarity complex, and the polarization of the founding member BSL1 coincides with the formation of the PPB (blue lines in the MMC) at the entry of MMC to mitosis. The participation of BSL proteins in the polarity complex may directly or indirectly dissociate BIN2 from the plasma membrane, releasing its inhibition on YDA MAPK signalling. Polarized BSL1 is inherited by the SLGC, in which its phosphatase function could directly activate YDA MAPK signalling, leading to strong suppression of SPCH and PC differentiation. Thus, we propose that polarized BSL1, by jointly regulating BIN2 GSK kinase and YDA MAPK activities, functions as a spatiotemporal molecular switch to establish a kinase-based signalling asymmetry that enables cell-fate asymmetry in the two daughter cells. See Discussion for more details. Graphics on top show the progressive stages of stomatal ACD in Arabidopsis. Dotted rectangles represent the regions enlarged at the bottom containing the polarity complex in the MMC (left), PPB-containing MMC (middle) and SLGC (right). Light blue, stomatal fate; pink, non-stomatal fate. NE, nuclear envelope; PM, plasma membrane. The question mark indicates unidentified regulator(s) for POLAR to associate with the polarity complex.

The function of BSL proteins in Arabidopsis stomatal development requires BIN2 and YDA.

We next determined whether the role of BSL proteins in stomatal development occurs as a consequence of its ability to modulate the activities of BIN2 and YDA (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 9c–e). We first examined the effects of altering BSL activity in the context of a loss-of-function bin mutant (carrying mutations in BIN2 and the two closely related genes BIL1 and BIL2), which produces fewer stomatal lineage cells in the leaf epidermis than wild-type plants (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 9f). We found that the formation of stomatal lineage cells in the loss-of-function bin mutant was unaffected by BSL1 overexpression (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 9e). Thus, the ability of BSL proteins to modulate Arabidopsis stomatal development requires BIN2. Next, we examined the effects of altering BSL activity in the context of a loss-of-function yda mutant, which overproduces stomatal GCs, or in the context of a constitutively active yda mutant, which does not produce stomata17 (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 9c,d). The formation of stomatal lineage cells in plants containing either the loss-of-function yda mutant or in plants containing a constitutively active yda allele was unaffected by BSL1 overexpression or the loss-of-function bsl-quad, respectively (Fig. 6b and Extended Data Fig. 9c,d). Thus, the ability of BSL proteins to modulate Arabidopsis stomatal development requires YDA. Taken together, these results establish that the ability of BSL proteins to modulate stomatal development requires the presence of both BIN2 and YDA. We conclude that the role of BSL in stomatal development occurs as a consequence of its ability to modulate the activities of BIN2 and YDA in stomatal lineage cells.

We also examined whether signalling components upstream of the YDA MAPK cascade are required for BSL function in stomatal development. Thus, we examined the effects of BSL1 overexpression in the context of plants containing loss-of-function mutations in members of the ERECTA family of receptor-like kinases30, in members of the SERK family of receptor-like kinases31 or in the receptor-like protein TMM27. We found that the effects of altering BSL activity on stomatal lineage cell formation in these mutant backgrounds was similar to that observed in wild-type plants (Extended Data Fig. 10a–d). Thus, in contrast to YDA and BIN2, the membrane receptors ERECTA, SERK and TMM are not required for BSL to function in Arabidopsis stomatal development.

Discussion

The polarization of BSL1 provides a spatiotemporal molecular switch for stomatal ACD in Arabidopsis.

Organogenesis in multicellular organisms requires cell proliferation and cell-fate differentiation events that are intricately controlled in time and space. Stomatal development has proven to be an effective system for studying the underlying mechanisms by which asymmetric cell division and fate determination are regulated in plants2,7,32,33. Here, we identified BSL protein phosphatases as key determinants of stomatal ACD in Arabidopsis. In particular, we demonstrated that the founding member BSL1 is timely polarized to the cell cortex of the MMC entering mitosis to enable the transition from MMC cell division to specification of SLGC cell-fate differentiation. Based on our findings, we propose a new mechanistic model for stomatal ACD that incorporates the critical function of BSL proteins in establishing cell-fate asymmetry (Fig. 6c).

In Arabidopsis stomatal ACD, BASL was first identified as a polarized key regulator that controls both division orientation and differentiation of daughter cell fates13. After years of work, with multiple components identified that associate with the polarity complex14,15,18,19, BASL seems to provide a platform that is stably maintained before, during and after ACD. The BRX proteins interact with BASL to become polarized, but their polarization occurs earlier than BASL and facilitates BASL to attach to the plasma membrane15,34. To achieve the many functions that the polarity complex provides during ACD, individual components of the polarity complex are either assembled at a certain time point or activities are controlled in a certain way to orchestrate the complicated and sometimes antagonistic cellular events. For example, by directly recruiting the MAPKK kinase YDA to the polarity complex, polarized BASL enriches and elevates MAPK signalling, which suppresses SPCH activity and stomatal formation18,35. This regulation is important for specification of the daughter cell fate (SLGC) after ACD but has to be tightly suppressed before ACD for the MMC to undergo cell division. The identification of BIN2 GSK3-like kinases that interact with the scaffold protein POLAR to participate in the polarity complex before ACD provided the mechanism by which YDA and MAPK signalling are properly suppressed in the MMC19. Therefore, prior work has shown that the differences in the composition and activity of the membrane-associated polarity complex in the ACD mother cell (MMC) versus the SLGC differentiating daughter cell are required for ACD. Here, we demonstrated that these essential changes occur as a consequence of BSL1 polarization at the entry of the MMC to cell division (Fig. 6c).

A striking feature of the BSL proteins we identified is the joint regulation of the MAPKK kinase YDA and the GSK3-like BIN2 kinases in stomatal development. In the MMC, BIN2 is recruited by POLAR to preferentially localize to the cell cortex, where POLAR is phosphorylated by BIN2 for turnover, leading to the dissociation of both POLAR and BIN2 from the polarity complex19 (Fig. 6c). While such a self-regulatory interaction of POLAR–BIN2 may contribute to the temporal control of BIN2 function needed for MMC division, the participation of BSL1 in the polarity complex can actively dissociate BIN2 from the cell cortex to enforce the nuclear partitioning of BIN2 at the right time (Fig. 6c). The observation that BIN2 nuclear partitioning is elevated by overexpression of an active BSL1 phosphatase but not the phosphatase-dead variant (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 4) indicates that BSL-mediated protein dephosphorylation and/or BSL1D584N-mediated interference of the functions of BSL family members may alter BIN2 subcellular partitioning. Although direct evidence is still lacking, a possible substrate of BSL is BIN2 itself, as a previous study23 of BR signalling showed that an activated BSL family member (BSU1) directly dephosphorylates BIN2. An altered phosphorylation status of BIN2 might affect its localization, as a general regulation, in plant cells because in root epidermal cells where no BASL is expressed12, BIN2 is indeed less nuclear in bsl-quad mutants (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Fig. 6g). In stomatal lineage cells, the BSL proteins may also dephosphorylate BASL so that an altered phosphorylation status of BASL and/or BIN2 may result in a weakened interaction of BASL–BIN2 and therefore changes in BIN2 localization (Fig. 6c). Our experiments did not detect an interference of BSL1 with the POLAR–BIN2 interaction (Extended Data Fig. 5b and 6e), which is possibly due to the lack of a physical interaction between BSL1 and POLAR (Extended Data Fig. 5c). A better understanding of the possible functional connection between BSL and POLAR–BIN2 requires future studies.

The second role of BSL proteins is the regulation of YDA and MAPK signalling in cell-fate specification (Fig. 5). First, the BSL-mediated BIN2 preferential nuclear partitioning in the SLGC release the direct inhibition of BIN2 on YDA at the cell periphery, thus increasing MAPK signalling to suppress stomatal fate. More importantly, we found that BSL1 directly binds to YDA and actives its kinase activity, leading to increased MAPK signalling (Fig. 5). The positive role of BSU1 on MAPK signalling was also recently identified in the immunity pathway36. Thus, BSL-induced elevated MAPK signalling in the SLGC results in an elevated phosphorylation and suppression of SPCH that is required for SLGC differentiation (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, BSL-induced nuclear repartitioning of BIN2 provides additional phosphorylation of SPCH for degradation and SLGC fate determination21. Thus, polarization of BSL proteins during MMC division synergizes the regulation of the key kinases YDA and BIN2 upstream of SPCH and establishes a kinase-based signalling asymmetry pathway enabling the production of daughter cells with distinct cell-division potential and cell-fate specification. The signalling asymmetry that occurs as a consequence of BSL polarization suppresses the division of the SLGC daughter but not the meristemoid daughter. Thus, BSL-mediated suppression of cell division allows the SLGC to differentiate into a PC while the meristemoid undergoes subsequent rounds of cell division before differentiating into a GC (Fig. 6c).

Connections between BSL1 polarization and cell cycle regulation.

A key objective for future work will be to identify factors that trigger BSL1 polarization in the MMC. The results presented in Fig. 3 show that the timing of BSL1 polarization in the MMC is highly correlated with the formation of the PPB; that is, the landmark structure for cell commitment to mitosis in plants37. The demonstration that BSL1 polarization coincides with the initiation of mitosis in ACD progenitor MMCs suggests that BSL1 polarization and cell cycle regulation are connected. Studies of ACD in other eukaryotes have identified several cell cycle regulators that impinge on the ACD machinery to promote asymmetric protein localization (for example, the Aurora and Polo kinases, cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs))38–41. Thus, signalling components that regulate the cell cycle in Arabidopsis may provide temporal cues that trigger BSL1 polarization in the MMC. Candidate regulators that have the potential to carry out this function include the Aurora kinases, which regulate formative cell division and patterning in lateral roots42, and A- and B-type CDKs, which promote the G2-M transition in plant mitosis43 and stomatal development44,45. Alternatively, factors involved in the assembly of the PPB may provide the temporal cue that triggers BSL1 polarization. Candidate factors that have the potential to carry out this function in Arabidopsis include members of a TON1–TRM–PP2A (TTP) protein complex that is required for PPB assembly46,47.

The polarization of BSL1 during stomatal development may be triggered by an ACD checkpoint.

The association of BSL proteins with the polarity complex occurs in response to a cellular mechanism that is responsive to the developmental state of the cell. We propose that a PPB orientation checkpoint (POC), which monitors the establishment of division-plane asymmetry, functions alongside canonical cell cycle checkpoints to ensure the fidelity of plant ACD. According to our proposal, the POC functions, at least in part, by inhibiting BSL1 polarization in the MMC before the PPB has been correctly placed. Unlike animal cell division, plant cell division does not involve centrosome formation. Instead, plant cell division involves the formation of spindles with axes perpendicular to the plane defined by the PPB. Thus, the POC we propose occurs in plant ACD would be functionally analogous to the spindle position checkpoint described in budding yeast48 and the centrosome orientation checkpoint described in Drosophila germ lines49.

In symmetric cell divisions, cell cycle checkpoints monitor the major cellular events (cell size, DNA integrity, chromosome replication and segregation) to ensure the fidelity of the cell cycle50. The absence of these checkpoints has deleterious consequences for the development of cells and organs. ACD requires additional checkpoints to ensure that the position and orientation of the spindle will result in the production of asymmetric daughter cells48,51. Accordingly, the absence of ACD checkpoints can result in stem cell overproliferation due to symmetric self-renewal or stem cell depletion due to symmetric differentiation of daughter cells. In this regard, stem cell overproliferation and stem cell depletion is precisely what we observed in plants in which BSL activity was perturbed.

Methods

Plant materials.

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was used as the wild type. All mutants are in the Col-0 background except for bin2–3;bil1;bil2, which was in the Wassilewskija (Ws-0) background. The BSLf T-DNA insertional mutants were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC), including bsl1–1 (SALK_051383), bsl1–2 (SALK_147279), bsl2–1 (SALK_055335), bsl2–2 (WiscDsLox245G08), bsl3–1 (SALK_071689), bsl3–2 (SALK_072437), bsu1–1 (SALK_030721) and bsu1–2 (SAIL_101_H03). The null alleles, bsl1–1 (SALK_051383), bsl2–1 (SALK_055335), bsl3–2 (SALK_072437) and bsu1–1 (SALK_030721), were used for generating high-order mutants and for phenotypic analysis. The bsl family mutants were confirmed by PCR-based genotyping. The following mutants and transgenic Arabidopsis lines have been previously reported: basl-2, BASLp::GFP–BASL;basl-2 and 35S::GFP–BASL;basl-2 (ref. 13); SPCHp::SPCH–CFP;spch-3 (ref. 12); yda-3 (Salk_105078)18; bsl-quad (null alleles of bsu1, bsl1 combined with RNA-interference-mediated silencing of BSL2 and BSL3) and bin2–3;bil1;bil2 (ref. 22); tmm27; er;erl1;erl2 (ref. 30); serk-quad31; and 35S::mCherry–TUA525. Primers for genotyping, PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) and quantitative real-time PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Growth conditions.

In general, Arabidopsis seeds were surface sterilized with 10% bleach and grown on half-strength Murashige and Skoog basal medium plates or in soil with 16-h light/8-h dark cycles at 22 °C. Wild-type N. benthamiana plants were grown under 14-h light and 10-h darkness at 25 °C.

Plasmid construction.

Gateway cloning technology (Invitrogen) was used for most DNA manipulations unless otherwise specified. For molecular cloning, the coding DNA sequences (CDS) and genomic DNA (gDNA) fragments of BSL1, BSL2, BSU1 and BIN2 were cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO vectors (Invitrogen) and for BSL3, the CDS was cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO. The phosphatase-dead BSL1D584N was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis of BSL1 CDS in pENTR/D/TOPO using a QuikChange II Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent). The kinase-inactive version of YDA (YDAKI containing the site mutation K429R)52 was cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO vectors. The BASL and TMM promoter sequences can be found in ref. 13 and ref. 27 and were subcloned into pDONR-P4-P1R, respectively (courtesy of D. Wengier). Double LR recombination reactions using LR Clonase II (Invitrogen) were performed to integrate pENTR/D containing the CDS or the gDNA of the gene of interest and pDONR promoter into the R4pGWB vectors53. To generate constructs for protein localization, the promoter regions of BSL1, BSL2, BSL3 and BSU1 were isolated by PCR using the primers specified in Supplementary Table 2 and inserted into the corresponding pENTR/D-CDS plasmids. For BIN2 protein fusion, the genomic fragment containing a 2.2-kb promoter and the genomic coding region of BIN2 was amplified and cloned into pENTR/D/TOPO, and then recombined into pHGY54. For transient protein expression in N. benthamiana, the pENTR/D vectors containing the coding sequences of BSL1, BSL2, BSL3, BSU1, BIN2, BASL or POLAR were recombined into pH35GC/Y54 or pGWB to generate p35S::BSLf–CFP, p35S::BSLf–FLAG, p35S::BIN2–YFP, p35S::4×Myc–BASL or p35S::4×Myc–POLAR. The pXNGW and/or pXCGW vectors were used for recombination reactions to generate the BiFC constructs. The resulting binary vectors mentioned above were confirmed by restriction enzyme digestion and DNA sequencing, then transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains GV3101 for Arabidopsis transformation and/or N. benthamiana leaf infiltration.

Confocal imaging and image processing.

Confocal images were acquired using a Leica TCS SP5 II microscope. The excitation/emission spectra for various fluorescent proteins are as follows: CFP, 458 nm/480–500 nm; GFP, 488 nm/501–528 nm; YFP, 514 nm/520–540 nm; mCherry, 543 nm/600–620 nm; RFP, 594 nm/600–620 nm; and propidium iodide (PI), 594 nm/591–636 nm. Images were taken from similar central areas in the adaxial side of developing cotyledons of Arabidopsis seedlings or N. benthamiana leaves. Cell outlines in Arabidopsis were visualized using PI (Invitrogen) staining. All imaging processing was performed using Fiji (ImageJ) software (http://fiji.sc/Fiji). Whenever possible, z-stacked images were obtained. Quantifications and statistical analyses were performed using Fiji and GraphPad Prism 5.1, respectively.

Recombinant protein expression, purification and in vitro pull-down assay.

To express recombinant proteins in E. coli, the coding region of BASL was cloned into a pET28a vector to generate His-tagged BASL. The coding region of BSL1 was cloned into pMAL-c2× and pGEX-4T-1 vectors to generate MBP-tagged BSL1 and GST-tagged BSL1, respectively. The coding region of BIN2 was cloned into a pGEX-4T-1 vector to generate GST-tagged BIN2. The coding regions of YDA was cloned into a pMAL-c2× vector to generate MBP-tagged YDA. The primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

All constructs were transformed into E. coli (BL21 strain), and recombinant protein expression was induced by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG; 0.5 mM) at 16 °C for 16 h. Bacterial cells were collected and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)). GST-tagged proteins were purified using Pierce glutathione superflow agarose (Thermo Scientific), whereas MBP-tagged proteins were purified with amylose resin (NEB) and His-tagged proteins were purified with Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

Purified proteins were used for in vitro pull-down assays. GST or GST–BSL1 proteins were immobilized on Pierce glutathione superflow agarose, which were then incubated with an equal amount of purified MBP-tagged YDA at 4 °C for 3 h. The beads were washed three times with the washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.5% Triton X-100). Proteins bound to the beads were mixed with 5× SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Samples were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). Protein was analysed by immunoblotting with anti-MBP (anti-MBP monoclonal antibody, NEB, E8032S; 1:5,000) or anti-GST (GST (91G1) rabbit monoclonal antibody 2625, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000) antibodies.

In vitro quantitative pull-down assays (Supplementary Fig. 5d) were performed as previously described19 to examine the different binding affinities of BIN2–BASL in the presence of BSL1. All testing proteins (MBP/MBP–BSL1, GST–BIN2 and His–BASL) were purified beforehand. To assay the interaction levels of BIN2–BASL, Ni-NTA agarose was first used to immobilize His–BASL, the mixture was then split into four tubes with an equal amount in each. For each reaction, the same amount of GST–BIN2 with an increasing amount of MBP–BSL1 or MBP (negative control) (1×, 5× and 10× concentrated) were added into the same amount of His–BASL and incubated at 4 °C for 3 h followed by washing buffer, SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting. The BIN2–BASL interaction strength was evaluated by calculating the amount of GST–BIN2 being pulled down with His–BASL. His–BASL was detected using anti-His antibody (2365, Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1,000). To quantify the protein amount on immunoblots, the band intensities (three independent repeats) were measured using Fiji. To generate the histograms, the relative amount of target protein (GST–BIN2) was first normalized to the BASL band intensity, and the amount of GST–BIN2 in the control reaction (His–BASL + GST–BIN2 without BSL1) was defined as 1.

In vitro kinase assay.

To evaluate the in vitro phosphorylation levels of YDA, 0.5 μg of purified MBP–YDA (EDTA-free) with or without BSL1–FLAG/BSL1D584N– FLAG fusion proteins purified from N. benthamiana leaf was incubated in 30 μl reaction buffer (5 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MnCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 10 μM cold ATP) at 30 °C for 30 min. Reactions were stopped by adding 6 μl of 5× SDS sample buffer. Protein samples were analysed on a Phos-tag acrylamide gel (50 μM, Wako Chemicals) that slows down the migration of phosphorylated proteins and separates YDA with different phosphorylation levels. Protein loading levels were performed by immunoblot analysis with an anti-MBP antibody (anti-MBP monoclonal antibody, NEB, E8032S; 1:5,000).

Transient expression in N. benthamiana and imaging analysis.

Agrobacterium strains GV3101 harbouring the constructs of interest in 10 ml of LB medium with appropriate antibiotics were cultured overnight. Bacterial cells were collected at 4,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2. The cell culture and p19 were mixed to reach an OD600 of 0.5 for each line and co-infiltrated into the week-old N. benthamiana abaxial leaves as previously described18. Co-infiltrated leaves were checked by confocal microscopy 3–4 days post-infiltration. To quantify the polarity degree of YFP in N. benthamiana epidermal cells, three independent replicate experiments were performed, and 26–28 representative cells for each combination were scored. Absolute fluorescence intensity values were measured using Fiji, and protein polarization values were calculated as described in ref. 18.

Co-IP assay in Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana.

To test in vivo the physical interaction between BSL1 and YDA, total cell protein was extracted from Arabidopsis plants (3-d.p.g. seedlings) co-expressing pTMM::BSL1–FLAG and pBASL::10×Myc–YDAKI. To perform the experiments, plant tissues were ground up in liquid nitrogen and then mixed with protein extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 and 1% (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, P 9599)). Protein extracts were centrifuged at 12,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min and the supernatants were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4 °C for 3 h. After incubation, the immunoprecipitated proteins with beads were washed three times with extraction buffer then mixed with 2×SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. Samples were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the corresponding primary antibodies (monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody produced in rabbit, F2555, Sigma-Aldrich; Myc-Tag (71D10) rabbit monoclonal antibody 2278, Cell Signaling Technology).

To test protein–protein interactions of BASL–BSL and BSL1–YDA in plant cells, total cell proteins were extracted from N. benthamiana leaves that transiently expressed the combinations of p35S::GFP or p35S::GFP–BASL with p35S::BSL1–FLAG, p35S::BSL2–FLAG, p35S::BSL3–FLAG or p35S::BSU1–FLAG and the combinations of p35S::YDAKI–YFP with p35S::BSL1–FLAG or p35S::BSU1–FLAG. To test the influence of BSL1/BSL1D584N (phosphatase-dead) on the interactions of BASL–BIN2 or POLAR–BIN2, total cell proteins were extracted from N. benthamiana leaves transiently co-expressing p35S::4×Myc–BASL/POLAR and p35S::BIN2–YFP in the presence of p35S::BSL1/BSL1D584N–FLAG. N. benthamiana leaves were collected and ground in liquid nitrogen with the same extraction buffer described above. Protein extracts were centrifuged at 18,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min and the supernatants were incubated with GFP-Trap agarose beads (Chromotek) at 4 °C for 3 h. Then, the beads were washed three times with extraction buffer, followed by mixing with 2× SDS sample buffer and boiling for 5 min. Samples were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and analysed using the corresponding primary antibodies (monoclonal anti-FLAG M2 antibody produced in mouse, F3165, Sigma-Aldrich; anti-GFP antibody, Roche (11814460001); Myc-Tag (9B11) mouse monoclonal antibody 2276, Cell Signaling Technology).

Immunoprecipitation–MS analysis.

Five grams of seedlings (expressing BASLp::GFP–BASL in basl-2, or 35Sp::GFP–BASL in Col-0 or BASLp::GFP in Col-0 at 3-d.p.g.) were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Total cell proteins were extracted with extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM NaF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail for plant cell extracts (Sigma-Aldrich, P 9599), 1% (v/v) NP-40). The homogenates were sonicated for 10 s in an ice bucket then diluted with extraction buffer without NP-40 to lower the NP-40 level to 0.2% (v/v). The protein mix was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to collect the supernatant. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured by aliquoting 50 μl for the protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad). The remaining supernatant was mixed with 100 μl GFP-Trap agarose (Chromotek) and incubated for 3 h on a rotating wheel at 4 °C. The beads were then collected by low-speed centrifugation and washed four times by resuspending in protein extraction buffer with 0.2% (v/v) NP-40. Next, 5× SDS sample buffer was added into the beads and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Protein samples were loaded onto 10% SDS–PAGE but run for a short distance, followed by gel reduction, alkylation and digestion with trypsin (sequencing grade, Thermo Scientific, 90058). Digested peptides in the gel were extracted twice with 5% formic acid, 60% acetonitrile and dried under vacuum.

Peptide samples were analysed by liquid chromatography (LC)–MS using a nano LC-MS/MS (Dionex Ultimate 3000 RLSC nano System) interfaced with a QExactive HF (Thermo Fisher). Peptides were loaded on to a fused silica trap column Acclaim PepMap 100, 75 μm × 2 cm (Thermo Fisher). After washing for 5 min at 5 μl min−1 with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, the trap column was brought in-line with an analytical column (Nanoease MZ peptide BEH C18, 130 A, 1.7 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm, Waters) for LC–MS/MS. Peptides were fractionated at 300 nl min−1 using a segmented linear gradient 4–15% B in 30 min (where A is 0.2% formic acid and B is 0.16% formic acid, 80% acetonitrile), 15–25% B in 40 min, 25–50% B in 44 min and 50–90% B in 11 min.

MS data were obtained using a data-dependent acquisition procedure with a cyclic series of a full scan acquired in Orbitrap with a resolution of 120,000 followed by MS/MS (HCD relative collision energy of 27%) of the 20 most intense ions and a dynamic exclusion duration of 20 s. The peak list of the LC–MS/MS were generated by Thermo Proteome Discoverer (v.2.1) into MASCOT Generic Format (MGF) and searched against Arabidopsis (TAIR v.10), plus a database composed of common laboratory contaminants using an in-house version of X!Tandem (GPM Furry55). Search parameters were as follows: fragment mass error: 20 ppm; parent mass error: ± −7 ppm; fixed modification: carbamidomethylation on cysteine; flexible modifications: oxidation on methionine; protease specificity: trypsin (C-terminal of R/K unless followed by P), with 1 miss-cut at preliminary search and 5 miss-cut during refinement. Only spectra with loge < −2 were included in the final report. LC–MS/MS analysis was performed at the Biological Mass Spectrometry facility of Rutgers University.

MAPK activation assay.

Total cell protein was extracted with extraction buffer (50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 10 mM DTT, 10 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM NaF, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, protease inhibitor cocktail for plant cell extracts (Sigma-Aldrich, P 9599), 1% (v/v) NP-40) from 3-d.p.g. Arabidopsis seedlings of Col-0, bsl1;bsl3, bsl-quad and pTMM::BSL1–YFP. The extracted total cell protein was resolved on 10% SDS–PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with a primary antibody against phosphor-p42/44 MAP kinase (1:1,000; Cell Signaling Technology). Total protein staining (Ponceau S) was used to confirm equal loading for immunoblots.

Yeast two-hybrid assay.

The full-length coding sequence of BSL1, BSL2, BSL3 or BSU1 was cloned and inserted into the pGBKT7 vector as bait. The full-length coding sequence of BASL was cloned into a pGADT7 vector. Constructs used for testing the interactions were co-transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain AH109 using an EZ-YEAST transformation kit (MP Bio-medicals) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The positive transformants were selected on SD/-Leu/-Trp medium. The interactions were tested on the SD/-Leu/-Trp/-His medium with an appropriate concentration of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT). Interactions were observed after 3 days of yeast growth at 30 °C.

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from 50 mg of seedlings at 3–5-d.p.g. with a RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was generated using a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis system (Invitrogen). Transcript levels of BSL1, BSL2, BSL3 and BSU1 were amplified with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2, and the reactions were set up using SYBR Select master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Actin2 was used as an internal control to normalize expression levels. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. Quantitative real-time PCRs were performed using a Stepone real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

For RT–PCR, two independent lines from each mutant were tested. The ribosomal S18 (RPS18) gene was used as an internal standard for normalization of gene expression levels. The sequences of all primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Stomatal quantification and protein polarity quantification.

In general, to examine stomatal phenotypes in development, 5-d.p.g. cotyledons were stained with PI (Invitrogen) to capture images from similar central regions of adaxial cotyledons. Images were captured using EC Plan-Neofluar (×20/0.5) lenses on a Carl Zeiss Axio Scope A1 fluorescence microscope equipped with a Progress MF CCD camera (Jenoptik). Typically, 12–20 individual seedlings were picked from each mutant or two representative T2 transgenic lines out of >12 independent transgenic events. Confocal images shown in the figures were false coloured with brightness/contrast adjusted using Fiji.

To quantify stomatal phenotypes, the epidermal cells were categorized by size and shape into three groups: GCs (pairs of kidney-shaped cells); stomatal lineage cells (small dividing cells, including MMCs, Ms and SLGCs); and PCs (puzzle-shaped epidermal cells and enlarged SLGCs with at least one obvious lobe). Quantification for the stomatal index (SI: number of stomata/total number of epidermal cells) and the stomatal lineage index (SLI: number of GC pairs + stomatal lineage cells over total number of epidermal cells) were calculated by counting cells in an area of 0.385 mm2 with the cell-counter plug-in in Fiji.

To quantify protein polarization (BSL1 and BASL) in different cell types in Arabidopsis, confocal images were taken from adaxial cotyledons of 10–15 representative seedlings at 36 h.p.g., 48 h.p.g. and 72 h.p.g. Cells were subdivided into four categories based on cell morphology combined with BASL expression patterns: PrCs, small rectangular cells with nuclear-only BASL; early MMCs, small rectangular MMCs expressing both nuclear and polarized BASL; late MMCs, elongated/asymmetric MMCs expressing nuclear and polarized BASL; and SLGCs, large daughter cells after cell division completed with polarized BASL. For each category, 30–50 individual cells were selected and scored for protein polar distribution. To measure protein polarization values, ratios of high fluorescence intensity values (a) over low fluorescence intensity values (b) along equal cell periphery lengths from the same cell were collected and calculated. For the cells with relatively uniform expression of fluorescent proteins, the a and b values were collected by measuring two randomly selected cell periphery with equal length.

To quantify SPCH expression pattern levels, seedlings expressing SPCH–CFP in the wild-type and bsl-quad mutants were stained with PI and images of the adaxial side cotyledon epidermis were captured by confocal microscopy. The numbers of CFP-positive stomatal lineage cells and total epidermal cells were counted with Fiji to obtain CFP-positive ratios.

Statistics and reproducibility.

All statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 5.1 software. To compare two normally distributed groups, unpaired two-tailed t-tests were used. For multiple comparisons between normally distributed groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test were used. For all figures, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005 and ***P < 0.0001. To count cell types and to quantify immunoblots, the grid and image counter plug-ins in ImageJ were used. The numbers of repetitions and replicates for each experiment are mentioned in the legends.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

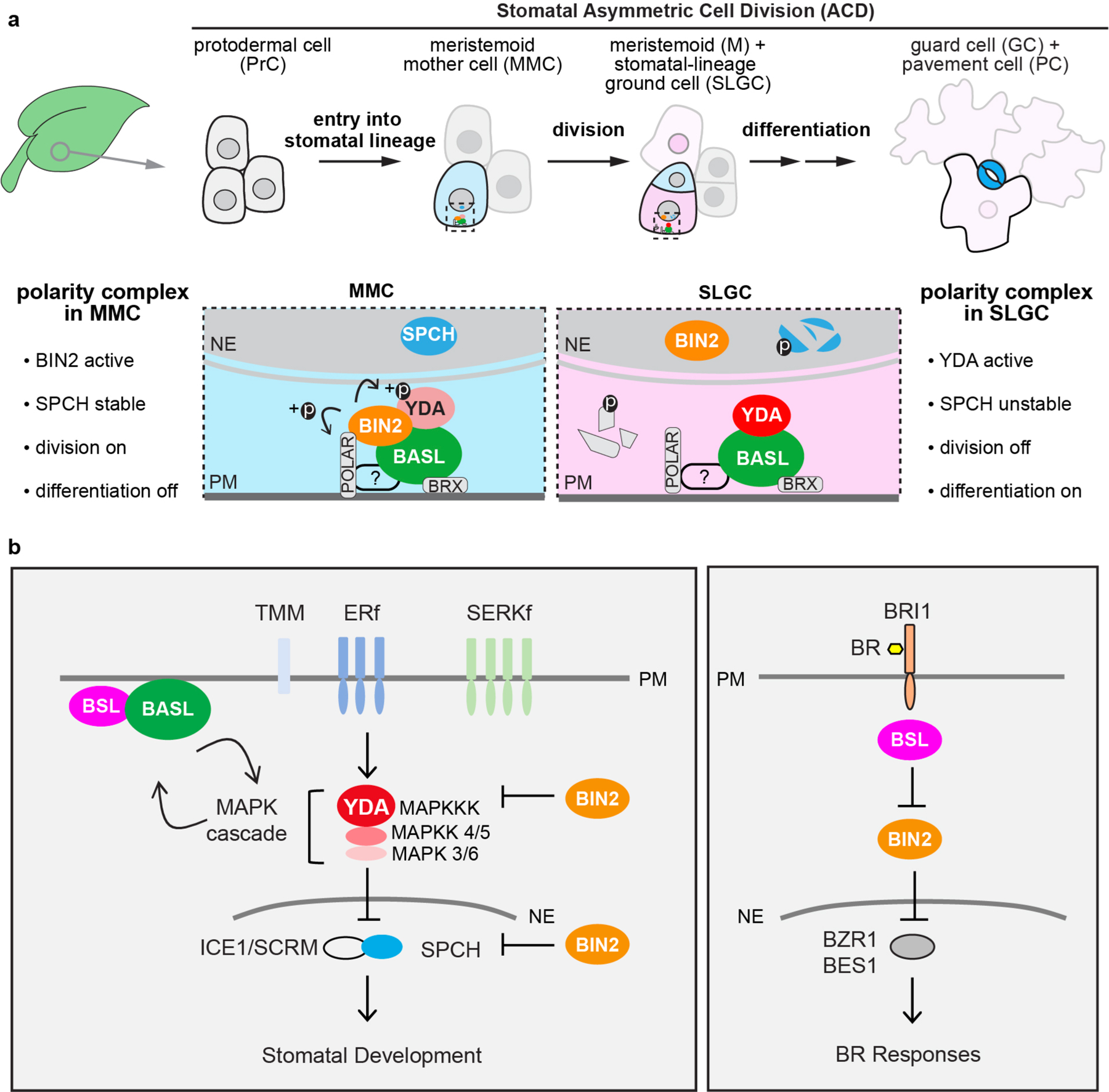

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Genetic Pathways Involving BSL Proteins in Arabidopsis.

a, Compositional and functional changes of the polarity complex before and after a stomatal ACD. In a young leaf, the initiation of the stomatal lineage cell (MMCs), is driven by the expression of the transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH)11. The plant-specific protein BASL is polarized before, during and after a stomatal ACD13. Multiple components in the BASL polarity complex have been identified to regulate cellular events in stomatal ACD. The BRX proteins interact with BASL to attach the polarity complex to the plasma membrane15. The POLAR proteins associate with the polarity complex and require BASL to become polarized14. It is known that POLAR recruits the BIN2 GSK3-like kinases to the polarity complex in the MMC, where BIN2 phosphorylates and inhibits the MAPKKK YDA, leading to alleviated MAPK-mediated suppression of SPCH, thereby the MMC undergoes cell division19. It is also known that, BASL interacts with YDA to locally concentrate MAPK signaling, thus SPCH is suppressed in the large daughter cell SLGC that inherits the polarity complex, thereby the SLGC after an ACD undergoes differentiation to become a pavement cell18,35. Thus, a successful stomatal ACD necessitates the changes of the key regulators, that is BIN2 to be preferentially membrane-localized before ACD but nucleus-partitioned after ACD, whereas YDA to be suppressed before ACD but activated after ACD. Light blue, stomatal fate; dark blue, stomatal guard cells; pink, non-stomatal fate; light pink, pavement cell. Fading cells, PrCs not converted to MMC become non-stomatal pavement cells. Dotted rectangle, regions enlarged in bottom, containing protein components of the polarity complex. Bottom, enlarged view of polarity protein complexes required for the progenitor cell (MMC, light blue) and the daughter cell (SLGC, pink), respectively, in stomatal ACD. ?, unidentified regulator/s for POLAR to associate with the polarity complex. Fragmented molecules (SPCH and POLAR) indicate proteins undergo degradation. b, Schematics depicting simplified signal transduction pathways in stomatal development (left) and Brassinosteroid (BR) signaling (right). The models are mainly based on Arabidopsis research. In stomatal development, the receptor-like kinases/protein (TMM, TOO MANY MOUTHS; ERf, ERECTA family; SERKf, SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE family)27,30,31 transduce signals from the EPF peptide ligands (not specified here) to activate the YODA (YDA) MAPK signaling that suppresses the transcription factors (SPCH, SPEECHLESS; ICE1/SCRM, SCREAM) and stomatal development17,20,56. The BIN2 GSK-3 like kinases regulate stomatal development by inhibiting YDA and SPCH21,22. The polarity protein BASL interacts with YDA and forms a positive feedback regulation with the MAPK cascade to regulate stomatal ACD18. In this study, we identified the BSL protein phosphatases as BASL partners in the polarity complex. In BR signaling, the hormone (BR) is perceived by the receptor-like kinase (BRI1, BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1)57 that triggers cytoplasmic signal transduction mediated by the BSL protein phosphatases23 and the BIN2 GSK3-like kinases58 to ultimately active the expression of the transcription factors (BZR1, BES1)59,60 for plant responses. Both pathways involve BSL Ser/Thr protein phosphatases and the GSK3-like BIN2 kinase. Block lines indicate negative regulation and arrows indicate positive regulation. PM, plasma membrane; NE, nuclear envelope.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. BSLf Physically Interact with BASL in Plants.

a-b, Co-IP assays using purified fusion proteins that are transiently overexpressed (driven by the ubiquitous 35S promoter) in N. benthamiana leaf cells. a, Results show physical association of FLAG-tagged BSL1/2/3 proteins with GFP-BASL. GFP-BASL (right) or GFP (left, control) was used as bait to bind to the GFP-Trap agarose. Immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by anti-FLAG. Data represent results of three biological repeats. b, Results show physical association of FLAG-tagged BSL1D584N (catalytically inactive BSL1 variant) proteins with GFP-BASL and BIN2-YFP. GFP alone (left, control), GFP-BASL (middle) or BIN2-YFP (right) was used as bait to bind to the GFP-Trap agarose. Immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by anti-FLAG. Data represent results of three biological repeats.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. BSL1, BSL2 and BSL3 Co-localize with BASL in Arabidopsis.

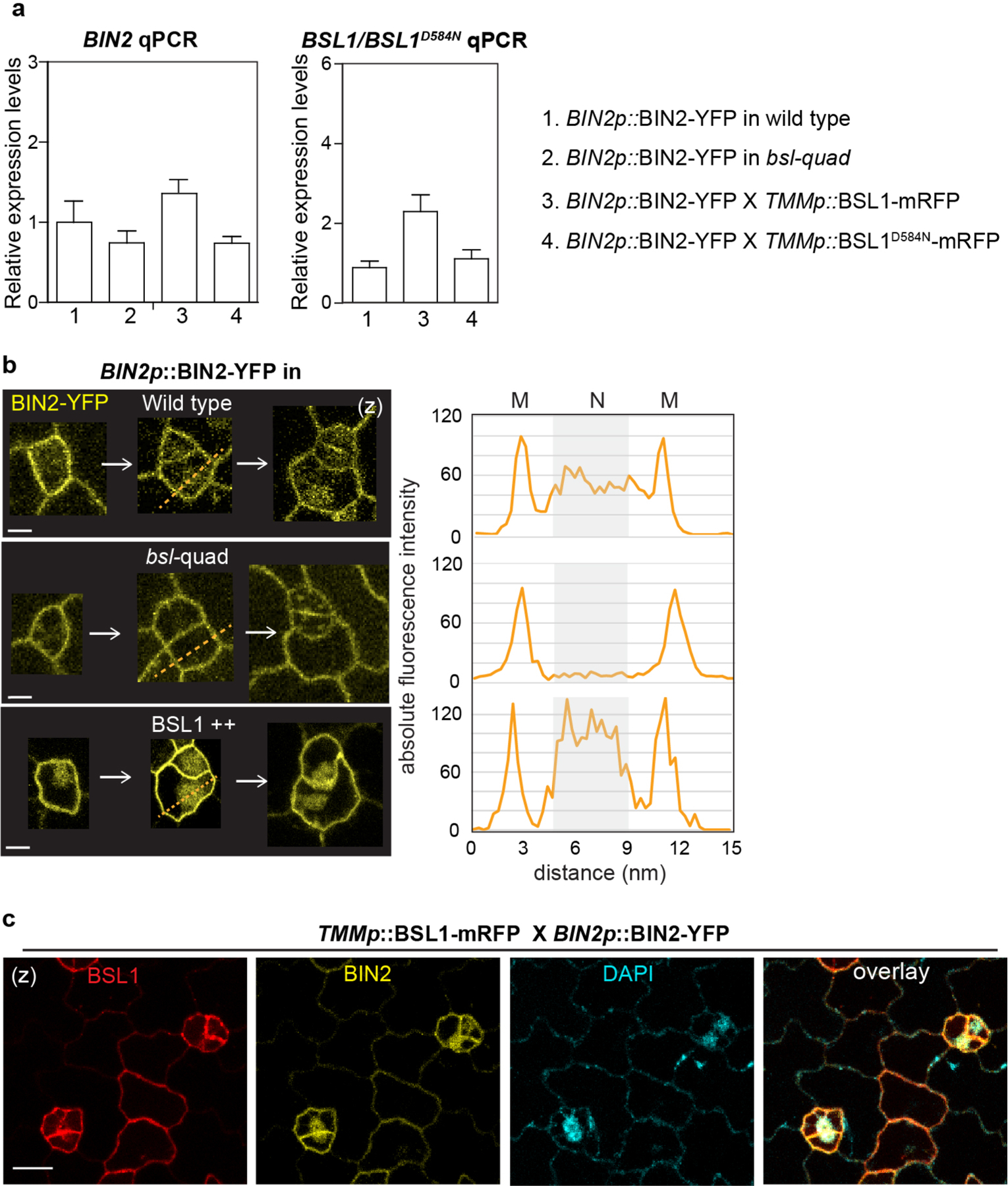

a, qPCR data show relative expression levels of BSL1 (driven by the native promoter) in bsl1 (left) or basl-2 (right). Three independent transgenic lines were used. Total RNAs were extracted from 3-day-old seedlings. Gene expression levels were normalized by ACTIN2 and relative expression levels of BSL1 were compared with the values in the wild type. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = three independent experiments. b, Co-expression of GFP-BASL (green) with BSL1-mRFP (magenta), both driven by the BASL promoter, in a true leaf of 5-dpg seedling. c, Representative images of co-localization of BSL1-mRFP, BSL2-mRFP and BSL3-mRFP (magenta) with GFP-BASL (green), all driven by the BASL promoter. Arrows mark protein polarization at the cell cortex. d, Expression patterns of endogenous promoter driven GFP-BASL (green) and BSL1-YFP (magenta) in progressive cell types during stomatal development. PrC (protodermal cells), early MMC (Meristemoid Mother Cell, small and rectangular), late MMC (asymmetrically expanded and triangle), M (Meristemoid), and SLGC (Stomatal Lineage Ground Cell). Protein polarizations were indicated by arrows. Scale bars in (b-d), 5 μm. e, qPCR data show relative expression levels of BASL and BSL in indicated genetic backgrounds. Total RNAs were extracted from 3-day-old seedlings. Gene expression levels were relative to ACTIN2. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = three independent experiments. Primers used were listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Association of BSL1 with the Polarity Complex Promotes BIN2 Partitioning to the Nucleus.

a, qPCR data show relative expression levels of BIN2 (left) and BSL1/BSL1D584N (right) in the indicated genetic backgrounds. Total RNAs were extracted from 3-day-old seedlings. Gene expression levels were normalized by ACTIN2 and relative expression levels of BIN2 or BSL1 were compared with the values in the wild-type background. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = three independent experiments. Primers used were listed in Supplementary Table 2. b, Representative confocal images show differential membrane/nuclear partitioning of BIN2 (yellow) in stomatal lineage cells from the wild type vs. in bsl-quad mutants vs. in BSL1 overexpression plants (driven by the TMM promoter). The expression of BIN2-YFP is driven by the native promoter. Right, florescence intensity profiling of the dotted lines drawn across the stomatal lineage cells shown on the left. Confocal images were taken with same settings and absolute fluorescence intensity values were obtained and profiled by Fiji. M, cell membrane; N, nucleus. Scale, 5 μm c, Co-expression of the TMM promoter driven BSL1-mRFP (red) with the endogenous promoter driven BIN2-YFP (yellow). The nuclear enrichment of BIN2 was verified by positive DAPI staining (cyan). Scale, 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. BSL1 Interferes the Interaction of BIN2-BASL in vitro.