Abstract

To date, diverse combination therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), particularly oncolytic virotherapy, have demonstrated enhanced therapeutic outcomes in cancer treatment. However, high pre-existing immunity against the widely used adenovirus human serotype 5 (AdHu5) limits its extensive clinical application. In this study, we constructed an innovative oncolytic virus (OV) based on a chimpanzee adenoviral vector with low seropositivity in the human population, named AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which endows the parental OV (AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3) with the ability to express full-length anti-human programmed cell death-1 monoclonal antibody (αPD-1). In vitro studies indicated that the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 retained parental oncolytic capacity, and αPD-1 was efficiently secreted from the infected tumor cells and bound exclusively to human PD-1 (hPD-1) protein. In vivo, intratumoral treatment with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 resulted in significant tumor suppression, prolonged overall survival, and enhanced systemic antitumor memory response in an hPD-1 knockin mouse tumor model. This strategy outperformed the unarmed OV and was comparable with combination therapy with intratumoral injection of AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 and systemic administration of commercial αPD-1. In summary, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 is a cost-effective approach with potential clinical applications.

Keywords: chimpanzee adenovirus, oncolytic virus, checkpoint inhibitors, PD-1, combination cancer therapy, alternative

Graphical abstract

The widely used oncolytic adenovirus in cancer immunotherapy is human serotype 5, but the high pre-existing immunity limits its extensive application. Now, we construct an innovative promising agent AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 and evaluate its antitumor efficacy in vitro and in vivo to diversify the countermeasures for clinical cancer treatment.

Introduction

In recent years, with the approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), cancer immunotherapy has made great progress in clinical applications.1 Ipilimumab, the first FDA-approved monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4), represents a milestone for ICI therapy.2 Notably, novel therapeutic antibodies targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1) exhibit fewer side effects compared with that of the anti-CTLA4 antibody and have been developed as a powerful strategy in the clinical treatment of multiple types of cancer.3, 4, 5

PD-1, also known as CD279, is mainly expressed on activated T cells and acts as a co-inhibitory molecule to regulate the extent of T cell activation.5,6 To obviate the recognition and elimination by cytotoxic T cells, the majority of tumor cells overexpress PD-L1 to yield downstream inhibitory signals and result in T cell dysfunction by interacting with PD-1.7 Thus, blocking the PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction with the responsible antibodies could rescue the T cell-mediated antitumor immune response.8 In general, ICI monotherapy fails to solve the “cold tumors” problem, which is often characterized by insufficient T cell infiltration, low PD-L1 expression, and defective antigen processing and presentation.9 According to previous studies, only approximately 10%–40% of patients with certain tumors could generate an inspiring response to ICI.10,11 Over the last several years, the ICI monotherapy field has been moving toward combination therapy, in which synergistic effects provide better therapeutic outcomes. For instance, the approved PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, or PD-L1 inhibitors, atezolizumab, avelumab, and durvalumab, were further explored in combination with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, oncolytic virotherapy, or other agents in preclinical and clinical studies.3,12,13

Among combination therapies, oncolytic virus (OV) represents a new category of therapeutic agent, demonstrating its advantage in specifically subverting tumor cells rather than targeting normal cells.14 This selective oncolysis effect upregulates PD-L1 expression in tumor cells and promotes antigen presentation, which further contributes to extensive T cell recruitment in the tumor site.15,16 Moreover, the suppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) resulting from regulatory T cells (Tregs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells can be converted by OV infection.17,18

A variety of viruses have been developed as OVs, including adenoviruses, poxviruses, herpes simplex virus (HSV), coxsackieviruses, and poliovirus, and adenoviruses have been developed as one of the most commonly used OVs because of its easily accessible genetic manipulation and well-investigated biology in both preclinical and clinical studies.19,20 Most previously established oncolytic adenoviruses are genetically engineered from AdHu5, but there are some drawbacks that restrict their broad application.20,21 Primarily, the Hexon of AdHu5 has a high affinity for blood coagulation factor X (FX), which leads to unanticipated uptake of viral particles by receptor-abundant liver cells.22 In addition, the majority of populations have neutralizing antibodies against AdHu5 because of prior exposure, which would cripple the antitumor effects in clinical settings. Hence development of novel OVs based on rare serotypes or other species is an avenue for overcoming this problem.

Despite the improved therapeutic efficacy of the combination of OV and ICI, the widespread clinical application may confront numerous challenges, encompassing the increased cost of the two drugs and the dependence on antibodies that already exist in the market. To exploit a better alternative, we generated an innovative oncolytic chimpanzee adenovirus armed with αPD-1 (AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) and tested its efficacy in different cancer cell lines and a human PD-1 (hPD-1) knockin mouse tumor model.

Results

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 cloning and replication

AdC68 was originally derived from chimpanzees and is closest to the subgroup E of human adenovirus, using coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR) for virus attachment.23 However, it is a distinct serotype with a low seroprevalence in the human population and cannot be cross-neutralized by antibodies against common human adenovirus serotypes because of the hypervariable regions of Hexon.24 Thus, we selected AdC68 to develop a promising oncolytic adenovirus for cancer therapy.

To enhance the selectivity of the oncolytic adenovirus in tumor cells, we introduced the survivin promoter (sp),25 which is hyperactive in tumor cells, to control the adenoviral replication-associated E1A gene (Figure 1A). To obtain the OV vector AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, we added the E1A gene driven by sp to the E1A region of replication-deficient adenovirus vector (AdC68-empty), which lacked the E1A, E1B, and E3B genes (Figure 1A). Furthermore, to generate αPD-1-expressing OV (AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1), we inserted the full-length antibody expression cassette of αPD-1 into the E3B region of the parental OV vector (AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3). The replication-deficient, αPD-1-expressing adenovirus AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 was constructed as a single antibody agent control by subcloning the αPD-1 expression cassette into the E3B region of the AdC68-empty vector.

Figure 1.

The E1A expression and viral replication of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in tumor cells

(A) The construction of the novel oncolytic adenovirus AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 and the control adenoviruses, including AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, and AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3. The ITR indicated the inverted terminal repeats of the adenoviral vector, and the E1A was driven by survivin promoter (sp) with whole E1B deleted. The expression cassette of αPD-1 was cloned into the E3B region. Concretely, the IgG heavy chain and light chain with individual signal peptide were linked by a F2A sequence and driven by CMV promoter. (B) The E1A expression was detected by qPCR at 24 h after cells were infected with the indicated adenoviruses at 10 MOIs. The relative mRNA levels were in reference to GAPDH. (C) The replication efficacy of the oncolytic adenoviruses (AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) in different cells was determined by TCID50 assay. The viral yields were presented as the ratios of TCID50 titer at 24 and 3 hpi, which indicated the fold change of the infectious progenies after the virus entered the cells. The statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. HC, heavy chain; LC, light chain; ns, no significance; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element.

As shown in Figure S1A, a panel of cells, including the human normal cell line (HFL-1), five human tumor cell lines (HCT-8, A549, Siha, NCI-H508, and Huh7), and three murine tumor cell lines (MC38, CT26.WT, and YUMM5.2) were infectable to AdC68. The infection rates in HCT-8 and CT26.WT were lower than that in other cells, which may result from lower levels of CAR in these cells. To investigate the expression of the E1A gene, all cells were infected with the four different adenoviruses (AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) at 10 multiplicities of infection (MOIs) and harvested at 24 h postinfection (hpi). As shown in Figure 1B, E1A mRNA levels were barely detectable in cells infected with AdC68-empty or AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1. The OV AdC68-spE1-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 exhibited significantly higher E1A mRNA levels in A549, Siha, NCI-H508, and Huh7 cells; modest in HCT-8, MC38, CT26.WT, and YUMM5.2; and lowest in HFL-1. Thus, the viral replication-associated E1A gene was activated more efficiently in tumor cells than in normal cells.

To verify whether these oncolytic adenoviruses replicated more efficiently in tumor cell lines, we examined the production of viral genomic DNA and infectious progenies by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay. As shown in Figures S1B and 1C, OVs replicated efficiently in A549, Siha, NCI-H508, and Huh7 cells and modestly in MC38 cells, which was higher than in HFL-1. However, although E1A expression and viral genomic amplification were also detected in HCT-8, YUMM5.2, and CT26.WT (Figures 1B and S1B), we barely detected the viral replication in these cells, which may relate to lower translation of viral late genes as reported by Young et al.26 that hampered the viral progenies production or other mechanisms that remained to be investigated. These data suggested that introducing the sp can efficiently increase adenovirus selectivity in certain types of tumor cell line. Notably, in all tested cell lines, there was no statistically significant difference between AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 and AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, suggesting that the presence of foreign αPD-1 did not affect the tumor-selective replication properties of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1.

Efficient expression of αPD-1 from tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1

The secretion of αPD-1 from the tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 was further confirmed. As shown in Figure 2A, the mRNA expression of αPD-1 was detected in cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 or AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 at both 24 and 48 hpi. Notably, the mRNA level of αPD-1 in AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1-treated cells was strikingly higher than that in AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, which was attributed to efficient viral genomic replication. In addition, the supernatants were harvested for western blot to identify whether the antibody was secreted and assembled correctly. A 150-kDa full-length band, 55-kDa heavy chain (HC), and 25-kDa light chain (LC) were identified under non-denaturing and denaturing conditions, suggesting that αPD-1 was properly assembled in Siha, NCI-H508, Huh7, and MC38 cells infected with AdC68-spE1-αPD-1 or AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 (Figure 2B). The specific concentrations of αPD-1 in the supernatants from NCI-H508 were higher than from MC38 at different time points, which resulted from relatively lower viral replication of AdC68-spE1-αPD-1 in MC38 cells (Figure S2). The binding affinity of αPD-1 to PD-1 is imperative for effectively blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. As shown in Figure 2C, compared with the commercial hPD-1 antibody, the expressed αPD-1 from NCI-H508 or MC38 cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 exhibited similar affinity and specificity to the hPD-1 protein, rather than bound to murine PD-1 (mPD-1) protein.

Figure 2.

The αPD-1 was expressed in AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1-infected tumor cells and bound to hPD-1 exclusively

(A) The αPD-1 mRNA was quantitated by qPCR at 24 and 48 h after cells were infected with the indicated adenoviruses at 10 MOIs. The relative mRNA levels were in reference to GAPDH, and the relative mRNA of cells infected with AdC68-empty was defined as 1. (B) The indicated tumor cells were infected with different adenoviruses at 20 MOIs. After 24 hpi, the expression of αPD-1 in the supernatants was detected through western blot under non-denaturing and denaturing conditions. (C) The affinity of the expressed αPD-1 to hPD-1 and mPD-1 protein. The supernatants from cells infected with AdC68-empty was used as a negative control, and the commercial hPD-1 antibody and mPD-1 antibody were used as positive controls. The statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

In summary, these results revealed that αPD-1 was successfully produced from tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which maintained species-specific affinity for the hPD-1 protein.

Oncolytic spectrum of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in vitro

To explore whether the antibody expression cassette affected the oncolytic activity of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, we incubated the cells with adenoviruses (AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) at MOIs ranging from 1 to 100. As depicted in Figure 3A, the viability of HFL-1 cells was barely reduced after infection with any adenovirus, even at a high MOI of 100. For the tumor cells, compared with the two replication-deficient adenoviruses (AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1), NCI-H508, Huh7, and Siha infected with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 exhibited prominent damage at both minimum (MOI = 1) and medium (MOI = 10) doses (Figures 3D–3F). Notably, despite their efficient replication in A549 cells, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 showed mild oncolytic effects on A549 cells at an MOI of 10 or 100 (Figure 3C). In addition, although viral replication was relatively weaker in MC38 than in human tumor cells, the OVs could show enhanced oncolytic effects when MOI was increased (Figure 3G). Consistent with the poor viral replication in HCT-8, YUMM5.2, and CT26.WT, the oncolytic effects of AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 on these cell lines were compromised even at an MOI of 100 (Figures 3B, 3H, and 3I).

Figure 3.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 induced tumor cell death in vitro

(A–I) HFL-1 (A), HCT-8 (B), A549 (C), Siha (D), NCI-H508 (E), Huh7 (F), MC38 (G), CT26.WT (H), and YUMM5.2 (I) were infected with adenoviruses at indicated MOIs for 72 h. The viability of different cells was measured by CCK-8 assay. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Taken together, compared with the parental OV (AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3), AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 possessed comparable tumor-target oncolytic activity in an MOI-dependent manner.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 induced tumor cell death through provoking apoptotic and autophagic pathways

Accumulating evidence has revealed that cell death can be executed by multiple pathways.27 To further investigate the mechanism by which AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 induced tumor cell death, we examined several mediators related to apoptosis and autophagy. Figure 4 showed that p62 was downregulated and LC3 was increased in both NCI-H508 and Huh7 cells treated with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 after 24 and 48 hpi, indicating that autophagy was triggered by AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, akin to AdHu5 killing of tumor cells.28 Caspase-3 is an effector caspase involved in apoptosis. Once activated, it proteolytically cleaves a range of substrates, such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP).29,30 The level of cleaved caspase-3 was augmented in tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 at 48 hpi. Notably, the level of cleaved PARP was significantly increased after AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 infection in NCI-H508 cells. The levels of p53 and its downstream molecule p21 did not change significantly in NCI-H508 cells, whereas they were increased in Huh7 cells treated with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1. Myeloid cell leukemia 1 (Mcl-1), which belongs to the B cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family, functions as a pro-survival regulator by sequestering pro-apoptotic members at the onset of apoptosis.31 It was significantly decreased in both tumor cells after treatment with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1. Moreover, a similar phenomenon as that with Mcl-1 was also observed in cell-cycle-associated proteins such as P(S780)-RB, CyclinD1, and CyclinE1.

Figure 4.

AdC68-spE1-αPD-1 induced tumor cell death by activating apoptotic and autophagic pathways

NCI-H508 and Huh7 cells were infected with the indicated adenoviruses at 20 MOIs. The cells were collected at 24 and 48 hpi to conduct the western blot assay under denaturing condition. The proteins p62, LC3 , cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, p53, p21, Mcl-1, CyclinD1, and CyclinE1 were analyzed. Actin was used as a loading control.

Altogether, these data suggested that AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 induced tumor cell death by activating the apoptosis and autophagy pathways.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 potently improved antitumor efficacy and induced a memory response in an hPD-1 mouse tumor model

To verify the antitumor effect of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in vivo, we established an immunocompetent hPD-1 knockin mouse tumor model, in which the ectodomain of the murine Pdcd1 (mPd1) gene was replaced by its human counterpart. As shown in Figure S3A, PD-1/PD-L1 downstream inhibitory signaling in this mouse was efficiently blocked by and the αPD-1 expressed from AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1-infected MC38 cells in vitro. Thus, this mouse model was appropriate for the evaluation of antitumor effect of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment in vivo. Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with MC38 (2 × 105 cells/mouse) into the right flank. When the tumor volume reached 50–100 mm3 (∼10 d postinoculation), the animals were administrated intratumorally either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or 2 × 107 plaque-forming units (PFUs) of AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 every 2 d for four doses in total (Figure 5A). In parallel, a combination therapy (intratumoral injection of AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 concurrent with intraperitoneal administration of the commercial αPD-1) was also set up. As shown in Figure 5B, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment was analogous to combination therapy, showing predominant tumor inhibition. In contrast, all mice in the PBS group or AdC68-empty exhibited rapid tumor progression, and the parental AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 or the single-expressed antibody control AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 led to only a slight delay in tumor growth. The tumor growth curves of individual mice were shown in Figure S3B. Notably, 50% of mice in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group (three of six) and 67% in the combination therapy group (four of six) were completely tumor free after the final treatment, while no mice in PBS, AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, or AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 groups attained tumor regression. The survival rates of the different groups were also consistent with the tumor inhibition results (Figure 5C). Furthermore, to investigate whether the tumor cells death was induced by AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment, we repeated the animal experiments and euthanized the mice on day 5 after the last treatment to strip the individual tumor. As shown in Figure 5D, the tumor weights of the AdC68-spE1-αPD-1-treated mice were significantly lower than those of the PBS, AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, or AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 group and were comparable with those of the combination treatment group. Notably, compared with the PBS group, the apoptosis in the AdC68-spE1-αPD-1 group was significantly enhanced, which was indicated by the elevated percentage of the TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL; one of the biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis32) tumor cells.

Figure 5.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 conferred potent antitumor effects in an hPD-1 knockin mouse tumor model

(A) Schematic of the treatment strategy in hPD-1 knockin C57BL/6 mouse tumor model. Mice were subcutaneously inoculated with 2 × 105 MC38 cells. When tumor volume arrived at 50–100 mm3, the mice were intratumorally treated with PBS or 2 × 107 PFUs of AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 every 2 d for a total of four times. A combination therapy (intratumoral injection of AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 with intraperitoneal inoculation of commercial αPD-1) was also implemented. (B) Tumor volume was measured every 2 d. (C) The overall survival was recorded. (D) The mice were euthanized on day 5 after last treatment, and the individual tumor was stripped and weighted. (E) The stripped tumors were used to perform immunochemistry, and the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was analyzed by ImageJ software. Three fields in each sample were randomly selected. (F) Mice cured from the indicated treatments were rechallenged with a higher dose of MC38 cells (5 × 105 cells/mouse) on day 150. Statistical differences in the tumor growth, animal survival, and tumor weight were determined by two-way ANOVA, log rank test, and unpaired t test, respectively. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Next, we validated whether AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment could activate tumor-specific memory responses. Mice cured from the indicated treatment groups (AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, n = 3; dual combination therapy, n = 4) were rechallenged with a higher dose of MC38 tumor cells (5 × 105 cells/mouse) in the contralateral flank on day 150. As shown in Figure 5E, tumors failed to form in the cured mice in either group within a 6-month observation (experiment terminated), whereas all naive mice formed tumors within 7 d.

In conclusion, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 exerted a significant antitumor effect and provoked a long-term antitumor response comparable with that of the combination therapy.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 enhanced the function of immune cells systemically

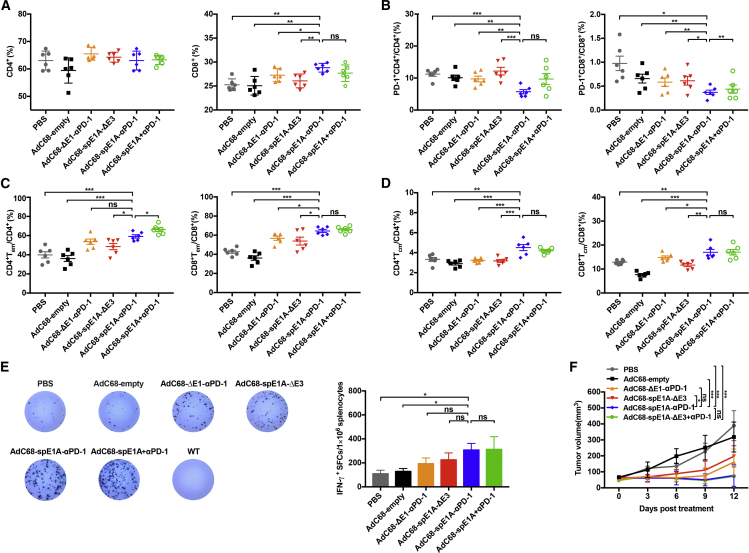

Previous studies have revealed that combination therapy could alter splenic immune status and strengthen systemic cellular immunity against tumor.33,34 Hence we repeated the animal experiments shown in Figure 5 and then determined whether AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment could enhance systemic tumoricidal response. Mouse spleens from each treatment group were collected on day 2 after treatment completion to investigate the profiles of T cells by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 6A, there was no significant difference in the percentage of CD4+ T cells among the different groups. Notably, CD8+ T cell levels were significantly augmented in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group when compared with those of PBS, AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, or AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 treatment groups but showed no statistical difference compared with that of the combination therapy group. Given that the expression level of the co-inhibitory molecule PD-1 plays a key role in T cell function, we determined the percentage of PD-1+ in the CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and found that AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment led to a significant PD-1+ reduction in both the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which indicated that T cell exhaustion was effectively reversed. In addition, the proportion of PD-1+ CD8+ T cells was lower in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment group than that in the combination therapy group (Figure 6B). Long-term protection from the same tumor rechallenges indicated that the memory response was intensified by AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 treatment; therefore, we further analyzed the levels of effector memory T cells (Tems) and central memory T cells (Tcms). The proportions of Tems (Figure 6C) and Tcms (Figure 6D) in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group were increased in both the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and exhibited statistical differences compared with those of PBS, AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, or AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 groups. However, there was no significant difference between the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 and combination therapy groups (except for the CD4+ Tems).

Figure 6.

AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 systemically enhanced the function of immune cells

All mice were euthanized on day 2 after the last treatment. The spleens were processed for flow cytometry and ELISpot assay. (A) The percentage of the CD4+ or CD8+ T cells gated from the CD3+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) The expression level of the immune inhibitor PD-1 in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was determined. (C and D) The percentages of effector memory T cells (Tems; CD44highCD62Llow) (C) and central memory T cells (Tcms; CD44highCD62Lhigh) (D) in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were also analyzed. (E) IFN-γ-secreting splenocytes were detected using ELISpot assay. The representative result is shown in the left panel, and the count of spots per 1 × 106 splenocytes is quantified in the right panel. Additionally, the WT mice exhibited the splenocytes from naive mice. (F) Tumor volume was measured every 2 d until the mice were euthanized. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Furthermore, tumor-specific T cell response was assessed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay (ELISpot). As shown in Figure 6E, when the splenocytes were stimulated with the same MC38 tumor cells, interferon (IFN)-γ production was significantly enhanced in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group compared with that in the PBS or AdC68-empty treatment groups. No response was elicited in naive (wild-type [WT]) mice. In addition, the tumor volumes of each group in this experiment were shown in Figure 6F, which exhibited a similar trend to that shown in Figure 5B.

Taken together, these data illustrated that local injection of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 could elicit systemic antitumor immunity, which contributed to therapeutic amelioration.

Discussion

The ICIs of PD-1 and PD-L1 have caused major breakthroughs in the field of immunotherapy; however, ICI monotherapy improves clinical outcomes only in certain cancer patients. Recently, combination strategies with other treatment modalities, highlighted with virotherapy, have been further explored, and promising results have been achieved in cancers that are less sensitive to ICI monotherapy.16,35,36

The first clinical indication of the combination of OV with ICI to enhance the antitumor efficacy was seen in a phase Ib study, carried out by Puzanov et al.37 They found that intratumoral injection of talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) with the systemic administration of anti-CTLA4 antibody (ipilimumab) greatly improved antitumor efficacy compared with that of T-VEC or ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma patients. Importantly, the timing of combination therapy implementation is critical for achieving optimum results. Liu et al.16 demonstrated that it was better to choose a concurrent administration of the OV and ICI because if the ICI was administered first, the OV would be cleared prematurely. When the ICI was administered too late, the upregulated immune checkpoint would be too high to be efficiently blocked. Therefore, making full use of the versatile OV platform to express ICI at the same time is a promising approach. Here, we engineered a novel OV, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which was based on the chimpanzee adenoviral vector AdC68, to efficiently express αPD-1 after infecting tumor cells. Our results showed that AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 demonstrated uncompromising viral replication and potent antineoplastic activity, which may promote the development of alternative options for combination immunotherapy.

The first report of an oncolytic adenovirus expressing a human full-length antibody, Ad5/3-Δ24αCTLA4, was raised by Dias et al.38 Their study showed that Ad5/3-24αCTLA4 significantly increased the anti-CTLA4mAb concentration in the TME and greatly improved the antitumor effect. Nevertheless, there were some deficiencies in this initial device for further clinical applications. Ad5/3-24αCTLA4 was less tumor specific for the E1 gene driven under the control of the endogenous promoter and could be neutralized by pre-existing antibodies against AdHu5.39 Here, a chimpanzee adenovirus (AdC68) that rarely circulates in humans was selected, and its E1A gene was engineered to be driven by a tumor-specific promoter (sp)24 to enhance cancer targeting. Moreover, apart from the deletion of protein E1B 55 kilodalton (KD), the E1B 19 KD was also deleted because it functions as a homolog of the cellular anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2, which could interact with the cellular proapoptotic proteins to suppress apoptosis during adenovirus infection.40 Thus, complete E1B removal would induce apoptosis in tumor cells more efficiently.

In light of the vectorization of αPD-1, a major concern was whether the tumor cells could produce correct and effective antibodies. Here, we confirmed that αPD-1 was efficiently expressed and properly assembled in various tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which demonstrated higher levels than those infected with AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1. Importantly, the expressed αPD-1 was specifically bound to hPD-1, but not mPD-1, and efficiently blocked the PD-1/PD-L1 signal pathway as the commercial antibody (Figure S3A).

The successful vectorization of ICIs has also been implemented in other OVs. Kleinpeter et al.41 vectorized three forms of a hamster monoclonal antibody against mPD-1(J43) in Western Reserve (WR) oncolytic vaccina virus and demonstrated that the full-length and the single-chain fragment variable (scFv) antibody showed better quality and higher affinity to mPD-1 than that of the antigen-binding fragments (Fab). Passaro et al.42 modified an oncolytic HSV1 to express a single-chain anti-PD-1 antibody and found that it induced a durable therapeutic effect in two types of mouse glioblastoma model. Zhu et al.43 constructed an oncolytic HSV2 encoding an anti-PD-1 antibody and showed that it significantly activated various immune effector cells, molecules, and complement pathway members, both in the TME and the systemic immune system. Nevertheless, not all OVs carrying ICIs can achieve noteworthy outcomes. The attenuated measles virus armed with antibodies against murine CTLA4 or PD-L1 only slightly delayed tumor growth, and all mice died eventually.44 The results of this study showed that the oncolytic chimpanzee adenovirus could synergize with the concurrently expressed αPD-1. In an hPD-1 knockin mouse tumor model, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 distinctly inhibited MC38 tumor progression and induced complete tumor regression in half of the mice.

It is noteworthy that the replication efficacy of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in MC38 cells was less efficient than that in some detected human tumor cells in vitro, but the therapeutic effects of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in the MC38 tumor model were promising. We suspected that the efficacy of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 was improved by enhancing the systemic adaptive antitumor response of the host. On one hand, albeit with relatively low efficacy, the viral replication of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 was still detected in MC38 tumor cells (Figure 1C); thus, we increased the treatment frequency as a strategy to improve the oncolysis effects. Under these conditions, as indicated in Figure 5E, immunogenic apoptosis was evaluated in oncolytic adenovirus-treated MC38 tumors, which played an important role in releasing tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), thus triggering adaptive immunity to recognize and attack tumor cells.45,46 On the other hand, tumor inhibition was correlated to the immunosuppressive molecular PD-1 in T cells. As shown in Figures 2 and S2, tumor cells infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 produced higher levels of αPD-1 than those infected with AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 in vitro. We also observed that PD-1 in T cells was more efficiently downregulated in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group than in the AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 group in vivo, suggesting that the PD1/PD-L1 signal was blockaded more effectively by higher levels of αPD-1 expressed by AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which was crucial to strengthen the function of tumor-specific T cells so that the IFN-γ secretion was elevated (Figure 6). Moreover, the upregulated systemic Tems and Tcms in the AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 group were indispensable for durable therapeutic outcomes and protection of mice from the same MC38 tumor rechallenge. Overall, compared with AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 and AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 significantly restored adaptive systemic antitumor immunity, and thus improved the therapeutic effects.

Compared with combination therapy, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 is conducive for efficient, low-cost, and more extensive clinical cancer treatment because it could avoid the high pre-existing immunity against AdHu5 in most humans. Furthermore, as some findings have reported, tumors can escape immune surveillance using many strategies.47 AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 was able to be combined or engineered with other immune-modulating agents with different mechanisms, such as cytokines and other inhibitors, as a monotherapy. However, the limitation of our study is that the distribution and metabolism of αPD-1 in vivo and the immune profile changes in the TME have not been evaluated. Moreover, hypothetically, the antitumor efficacy may be further improved in humanized tumor models, because we observed that the replication and oncolytic efficiency of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 were higher in human tumor cells. In the future, we plan to further evaluate the therapeutic effect of AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 in humanized tumor models and explore the underlying mechanisms intensively and comprehensively.

In conclusion, we constructed a novel OV, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, which combined OV and ICI in one agent and achieved enhanced antitumor efficacy. This novel single agent diversifies the countermeasures for cancer treatment and deserves further investigation.

Materials and methods

Cells

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells, human normal lung fibroblast cell line (HFL-1), human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (HCT-8), human colorectal carcinoma cell line (NCI-H508), human hepatocarcinoma cell line (Huh7), and murine melanoma cell line (YUMM5.2) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). The human lung carcinoma cell line (A549), human cervical carcinoma cell line (Siha), and murine colon carcinoma cell line (CT26.WT) were bought from the Cell Bank of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Science (Shanghai, China). Murine colon adenocarcinoma cell line (MC38) was purchased from Shanghai Langzhi Biotech (Shanghai, China). These cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and antibiotics and maintained in cell incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C.kD

Construction of adenoviruses

The adenoviral plasmid AdC68-empty generated in our lab deleted the E1 and E3B regions.48 To construct the parental OV AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, we fused the sp with the E1A gene (spE1A) by overlapping PCR and then cloning into the E1 region of AdC68-empty. Next, to obtain AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, we acquired the variable genes encoding the HC and LC of the anti-hPD-1 monoclonal antibody (nivolumab) from the IMGT database and combined them with the MHC class I signal sequence and constant sequence of human immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4). To facilitate efficient and apparent equimolar expression of HC and LC, we introduced a self-processing 2A sequence.49 After humanized optimization, the antibody codons were synthesized by GenScript Biotech (Nanjing, China) and subsequently cloned into the pShuttle plasmid (Clontech, San Francisco, CA, USA) with cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter through NheI and KpnI digestion to obtain pShuttle-CMV-αPD-1. Subsequently, to obtain AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, we inserted the CMV-αPD-1 expression cassette into the E3B region of the oncolytic plasmid AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 by seamless cloning. The replication-deficient single-antibody control AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 was generated using the same approach as described above.

The adenovirus plasmids constructed above were linearized with PacI and transfected into HEK293 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). When the adenoviruses were rescued, they were amplified in HEK293 cells and purified through CsCl density gradient ultracentrifugation.

The viral PFUs were determined using the TCID50 assay. The adenovirus was serially diluted in DMEM containing 5% FBS and added to HEK293 cells in a 96-well plate. Seven to ten days later, the cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed under a microscope to calculate the TCID50 using the Reed and Muench method.50 The conversion of TCID50 to PFU was based on the formula: PFUs/mL = 0.7 × TCID50/mL.

qPCR

HFL-1, HCT-8, A549, Siha, NCI-H508, Huh7, MC38, CT26.WT, and YUMM5.2 were seeded in a six-well plate (1 × 106 cells/well) and cultured overnight. The cells were infected with adenoviruses (AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) at an MOI of 10. After 24 and 48 h, the cells were collected and washed twice with PBS to extract the whole DNA for the detection of viral genomic amplification by measuring Hexon, and the whole RNA for the analysis of mRNA expression of E1A and αPD-1 using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then 1 μg of total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Hexon, E1A, and αPD-1 were quantified using a real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The corresponding primer pairs used were as follows: Hexon primer-F-5′-AACTACCCCTACCCGCTCAT -3′and primer-R- 5′-CCCTGTCGCAGAGGAACTTT-3′; E1A primer-F, 5′-ATCCCAATGAGGAGGCGGTA-3′ and primer-R, 5′- ATGCAGTGAAGAGTCGCTGT-3′; and αPD-1 primer-F, 5′-GAAGGGCCGATTCACCATCT-3′ and primer-R, 5′-AGTAGTCGTCGTTTGTCGCA-3′. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the internal reference, and the primer pairs used were: primer-F, 5′-CAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT-3′and primer-R, 5′-GTCCTCAGTGTAGCCCAAGATG-3′; and primer-F, 5′-CAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT-3′ and primer-R, 5′-GTCCTCAGTGTAGCCCAAGATG-3′ for humans and mice, respectively. The relative mRNA expression of AdC68-empty-infected samples was defined as 1. Data were analyzed using 7900HT System SDS software (Applied Biosystems).

Viral progenies production

The TCID50 assay was performed to examine viral replication. Different cells were seeded in 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) and infected with the oncolytic adenoviruses (AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) at 10 MOIs. The cells were collected at 3 and 24 hpi and washed twice with PBS. Then the cells were resuspended in 1 mL of DMEM containing 5% FBS and subjected to three rounds of freezing/thawing (−80°C/37°C). After centrifugation, the supernatant was added to the HEK293 cells by serial dilution in a 96-well plate. After 10 d, the TCID50 titer of each sample was calculated using the Reed and Muench method. The viral yields of each sample were presented as the ratios of TCID50 titer at 24 h and TCID50 titer at 3 h, which indicated the production of infectious progenies after the virus entered the cells.

Western blot

Siha, Huh7, NCI-H508, and MC38 were seeded in a six-well plate (1 × 106 cells/well) and cultured overnight. The cells were infected with adenoviruses (AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, or AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1) at 20 MOIs. Supernatants were harvested at 24 hpi for western blot analysis under non-denaturing and denaturing conditions. After sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking with 5% milk for 2 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-human IgG (H&L) (Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

To analyze the signaling pathways, we infected the NCI-H508 and Huh7 cells with different adenoviruses at 20 MOIs. After 24 and 48 hpi, the cells were collected, washed twice with PBS, and lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with protein inhibitors (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Furthermore, the protein concentration of each sample was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Beyotime Biotechnology) to ensure that the loading amount was equal, and the PVDF membrane was incubated with the primary antibody against p62, LC3, P(S780)-RB, cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, p53, p21, Mcl-1, CyclinD1, CyclinE1, and Actin, respectively. After that, the membrane was incubated with the secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

NCI-H508 and MC38 tumor cells were infected with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1 and AdC68-empty at 20 MOIs. Antibody concentrations in the supernatants were determined using a sandwich ELISA. Anti-human IgG kappa (70 ng/well) (catalog number [cat. #] 2060-01; Southern Biotech) was coated onto the ELISA plate at 4°C overnight and blocked with 5% skim milk (200 μL/well) for 2 h at 37°C. After blocking, the supernatants and the commercial hPD-1 antibody were diluted in suitable proportions and added to the plate (100 μL/well) for 2 h at 37°C. The secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-human IgG Fc (100 μL/well), was added and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Finally, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (New Cell & Molecular Biotech, Suzhou, China) was added, and the reaction was stopped with 2 M sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution (50 μL/well). Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). According to the standard curve formed by the commercial hPD-1 antibody, the concentrations of the expressed αPD-1 were calculated.

The affinity of the expressed αPD-1 to PD-1 protein was also detected by the same sandwich ELISA as above, while the coating proteins were changed by hPD-1 protein or mPD-1 protein (100 ng/well), and the secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG Fc and goat anti-human IgG Fc (100 μL/well), was added. Commercial hPD-1 and mPD-1 antibodies (Sino Biological, Beijing, China) were used as controls.

Cell oncolytic assay

The HFL-1 cells and a series of tumor cells (HCT8, A549, Siha, NCI-H508, Huh7, MC38, CT26.WT, and YUMM5.2) were seeded in a 96-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well) and cultured overnight. The four adenoviruses AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, and AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 were 10-fold serially diluted from 100 to 1 MOI in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS and infected cells in triplicate. Cells without infection were used as controls. After 72 h, cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting kit-8 (New Cell & Molecular Biotech, Suzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Absorbance was read at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Animal study

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Biosafety Committee of the Institut Pasteur of Shanghai (approval number: A20180401). The hPD-1 knockin C57BL/6 mice, in which the mPdcd1 gene exon 2 was substituted by the human counterpart, were purchased from Biocytogen (Beijing, China). Mice aged 6–8 weeks were subcutaneously inoculated with 2 × 105 MC38 tumor cells in the right dorsal flank. When the tumor volume reached 50–100 mm3, they were randomly divided into six groups and subjected to intratumoral treatment with PBS (100 μL) or 2 × 107 PFUs of AdC68-empty, AdC68-ΔE1-αPD-1, AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3, AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1, or combination therapy with intratumoral injection of AdC68-spE1A-ΔE3 plus intraperitoneal administration of commercial αPD-1 (200 μg/mouse). The treatments were conducted at an interval of 2 d and four times in total. The tumor volume was measured with a digital caliper every 2 d, and survival was monitored. Additionally, during the experiments, the mice were euthanized once the tumor volume reached 2,000 mm3 (tumor volume = length width2/2). The spleens were collected 2 d after the final treatment for flow cytometry analysis and ELISpot assay, and the tumors were isolated 5 d after the final treatment for weighing and immunohistochemistry.

For the tumor rechallenge assay, mice treated with AdC68-spE1A-αPD-1 or the combination therapy, which survived up to 150 d, were rechallenged with a higher dose of MC38 tumor cells (5 × 105 cells/mouse) in the contralateral flank. Naive mice that received the same dose of MC38 tumor cells were used as controls.

Immunohistochemistry

The stripped tumors were fixed with 1 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight, dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections. DNA fragmentation was determined using the TUNEL, as described by the manufacturer (Recordbio, Shanghai, China). Slides were scanned and observed under a Leica optical microscope (Leica Biosystems Imaging, CA, USA). Immunohistochemical analysis of the TUNEL-positive cells was performed using ImageJ software.

Flow cytometry analysis

Red cells were removed from the splenocytes collected from the different treatment groups using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology), and the cleared splenocytes were filtered with a 70-μm cell strainer. The cells were incubated with an anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (cat. #553142; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 4°C for 15 min for Fc block. Cell viability was determined using the LIVE/DEAD Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (cat. #L34957; Invitrogen). Then the cells were stained with antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, PD-1, CD44, and CD62L on ice for 30 min. All samples were analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer, and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

In detail, the antibodies used were anti-CD3-AF488 (cat. #100210; BioLegend), anti-CD4-AF700 (cat. #557956; BD Biosciences), anti-CD8-allophycocyanin (APC) (cat. #100712; BioLegend), anti-PD-1-PE (cat. #12-9969-42; eBioscience), anti-CD44-percpcy5.5 (cat. #103031; BD Biosciences), and anti-CD62L-BV421 (cat. #562910; BD Biosciences).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISpot) assay

To analyze the function of tumor-specific T cells secreting IFN-γ, we performed ELISpot assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Mabtech, Nacka Strand, Sweden). Ninety-six-well ELISpot plates (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) were activated with 35% ethanol, and then coated with antibodies against IFN-γ (AN18; Mabtech) at 4°C overnight. The plates were then washed with PBS five times and blocked with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS for 30 min at room temperature. Splenocytes (3 × 105 cells/well) from different treatment groups and naive mice (WT) were added to the plates and stimulated with MC38 tumor cells (2 × 104 cells/well). After incubation for 48 h in a cell incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C, the cells were discarded, and the plates were washed with PBS five times. Next, the plates were incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ detection antibody (R4-6A2-biotin; Mabtech) diluted in PBS containing 0.5% FBS for 2 h, and then diluted HRP-conjugated streptavidin was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, immune spots were formed by reacting with the substrate TMB and then counted with the ImmunoSpot Analyzer (Cellular Technology, Kennesaw, GA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software version 7.0. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), two-way ANOVA, unpaired t test, or log rank test. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), wherein ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and nsp, no significance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870922, 32070926, 31670946, and 32070928) and the key project of Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (20JCZDJC00090).

Author contributions

D.Z. and Z.H. conceived, designed, and supervised the entire study. P.Z. conducted all experiments and wrote the manuscript. X.W., M.X., X.Y., M.W., H.S., C.Z., X.W., and Y.G. analyzed and validated the results. D.Z., Y.G., and S.T. edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed and proofed the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2022.04.007.

Contributor Information

Zhong Huang, Email: huangzhong@ips.ac.cn.

Dongming Zhou, Email: zhoudongming@tmu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Xu W., Atkins M.B., McDermott D.F. Checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy in kidney cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020;17:137–150. doi: 10.1038/s41585-020-0282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagchi S., Yuan R., Engleman E.G. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: clinical impact and mechanisms of response and resistance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2021;16:223–249. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-042020-042741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma P., Allison J.P. Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell. 2015;161:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley R.S., June C.H., Langer R., Mitchell M.J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:175–196. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsaab H.O., Sau S., Alzhrani R., Tatiparti K., Bhise K., Kashaw S.K., Iyer A.K. PD-1 and PD-L1 checkpoint signaling inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: mechanism, combinations, and clinical outcome. Front. Pharmacol. 2017;8:561. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munn D.H., Bronte V. Immune suppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016;39:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahoney K.M., Rennert P.D., Freeman G.J. Combination cancer immunotherapy and new immunomodulatory targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:561–584. doi: 10.1038/nrd4591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalian S.L., Drake C.G., Pardoll D.M. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galon J., Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber J., Thompson J.A., Hamid O., Minor D., Amin A., Ron I., Ridolfi R., Assi H., Maraveyas A., Berman D., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study comparing the tolerability and efficacy of ipilimumab administered with or without prophylactic budesonide in patients with unresectable stage III or IV melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:5591–5598. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-09-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postow M.A., Chesney J., Pavlick A.C., Robert C., Grossmann K., McDermott D., Linette G.P., Meyer N., Giguere J.K., Agarwala S.S., et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan M.K., Postow M.A., Wolchok J.D. CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathway blockade: combinations in the clinic. Front. Oncol. 2015;4:385. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galluzzi L., Humeau J., Buqué A., Zitvogel L., Kroemer G. Immunostimulation with chemotherapy in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020;17:725–741. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0413-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi T., Song X., Wang Y., Liu F., Wei J. Combining oncolytic viruses with cancer immunotherapy: establishing a new generation of cancer treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:683. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaurasiya S., Fong Y., Warner S.G. Optimizing oncolytic viral design to enhance antitumor efficacy: progress and challenges. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1699. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z., Ravindranathan R., Kalinski P., Guo Z.S., Bartlett D.L. Rational combination of oncolytic vaccinia virus and PD-L1 blockade works synergistically to enhance therapeutic efficacy. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14754. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Vries C.R., Kaufman H.L., Lattime E.C. Oncolytic viruses: focusing on the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22:169–171. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2015.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chon H.J., Lee W.S., Yang H., Kong S.J., Lee N.K., Moon E.S., Choi J., Han E.C., Kim J.H., Ahn J.B., et al. Tumor microenvironment remodeling by intratumoral oncolytic vaccinia virus enhances the efficacy of immune-checkpoint blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:1612–1623. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nettelbeck D.M. Cellular genetic tools to control oncolytic adenoviruses for virotherapy of cancer. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2008;86:363–377. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuryk L., Møller A.S.W., Jaderberg M. Combination of immunogenic oncolytic adenovirus ONCOS-102 with anti-PD-1 pembrolizumab exhibits synergistic antitumor effect in humanized A2058 melanoma huNOG mouse model. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8:e1532763. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2018.1532763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulvihill S., Warren R., Venook A., Adler A., Randlev B., Heise C., Kirn D. Safety and feasibility of injection with an E1B-55 kDa gene-deleted, replication-selective adenovirus (ONYX-015) into primary carcinomas of the pancreas: a phase I trial. Gene Ther. 2001;8:308–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddington S.N., McVey J.H., Bhella D., Parker A.L., Barker K., Atoda H., Pink R., Buckley S.M., Greig J.A., Denby L., et al. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell. 2008;132:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen C.J., Xiang Z.Q., Xiang Z.Q., Gao G.P., Ertl H.C.J., Wilson J.M., Bergelson J.M. Chimpanzee adenovirus CV-68 adapted as a gene delivery vector interacts with the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor. J. Gen. Virol. 2002;83:151–155. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-1-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farina S.F., Gao G.P., Xiang Z.Q., Rux J.J., Burnett R.M., Alvira M.R., Marsh J., Ertl H.C.J., Wilson J.M. Replication-defective vector based on a chimpanzee adenovirus. J. Virol. 2001;75:11603–11613. doi: 10.1128/jvi.75.23.11603-11613.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junichi Kamizono S.N., Kosai Ki, Nagano S., Murofushi Y., Komiya S., Fujiwara H., Matsuishi T., Ken-ichiro K. Survivin-responsive conditionally replicating adenovirus exhibits cancer-specific and efficient viral replication. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5284–5291. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young A.M., Archibald K.M., Tookman L.A., Pool A., Dudek K., Jones C., Williams S.L., Pirlo K.J., Willis A.E., Lockley M., McNeish I.A. Failure of translation of human adenovirus mRNA in murine cancer cells can be partially overcome by L4-100K expression in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:1676–1688. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroemer G., Galluzzi L., Vandenabeele P., Abrams J., Alnemri E.S., Baehrecke E.H., Blagosklonny M.V., El-Deiry W.S., Golstein P., Green D.R., et al. Classification of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2009. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:3–11. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito H., Aoki H., Kuhnel F., Kondo Y., Kubicka S., Wirth T., Iwado E., Iwamaru A., Fujiwara K., Hess K.R., et al. Autophagic cell death of malignant glioma cells induced by a conditionally replicating adenovirus. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006;98:625–636. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tewari M., Quan L.T., O'Rourke K., Desnoyers S., Zeng Z., Beidler D.R., Poirier G.G., Salvesen G.S., Dixit V.M. Yama/CPP32β, a mammalian homolog of CED-3, is a CrmA-inhibitable protease that cleaves the death substrate poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Cell. 1995;81:801–809. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90541-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen G.M. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997;326:16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas L.W., Lam C., Edwards S.W. Mcl-1; the molecular regulation of protein function. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2981–2989. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majtnerova P., Rousar T. An overview of apoptosis assays detecting DNA fragmentation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018;45:1469–1478. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh C.M., Chon H.J., Kim C. Combination immunotherapy using oncolytic virus for the treatment of advanced solid tumors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7743. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribas A., Dummer R., Puzanov I., VanderWalde A., Andtbacka R.H.I., Michielin O., Olszanski A.J., Malvehy J., Cebon J., Fernandez E., et al. Oncolytic virotherapy promotes intratumoral T cell infiltration and improves anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;170:1109–1119.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scherwitzl I., Hurtado A., Pierce C.M., Vogt S., Pampeno C., Meruelo D. Systemically administered sindbis virus in combination with immune checkpoint blockade induces curative anti-tumor immunity. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2018;9:51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woller N., Gurlevik E., Fleischmann-Mundt B., Schumacher A., Knocke S., Kloos A.M., Saborowski M., Geffers R., Manns M.P., Wirth T.C., et al. Viral infection of tumors overcomes resistance to PD-1-immunotherapy by broadening neoantigenome-directed T-cell responses. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:1630–1640. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puzanov I., Milhem M.M., Minor D., Hamid O., Li A., Chen L., Chastain M., Gorski K.S., Anderson A., Chou J., et al. Talimogene laherparepvec in combination with ipilimumab in previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016;34:2619–2626. doi: 10.1200/jco.2016.67.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dias J.D., Hemminki O., Diaconu I., Hirvinen M., Bonetti A., Guse K., Escutenaire S., Kanerva A., Pesonen S., Loskog A., et al. Targeted cancer immunotherapy with oncolytic adenovirus coding for a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for CTLA-4. Gene Ther. 2012;19:988–998. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tatsis N., Lasaro M.O., Lin S.W., Haut L.H., Xiang Z.Q., Zhou D., Dimenna L., Li H., Bian A., Abdulla S., et al. Adenovirus vector-induced immune responses in nonhuman primates: responses to prime boost regimens. J. Immunol. 2009;182:6587–6599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lomonosova E., Subramanian T., Chinnadurai G. Mitochondrial localization of p53 during adenovirus infection and regulation of its activity by E1B-19K. Oncogene. 2005;24:6796–6808. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinpeter P., Fend L., Thioudellet C., Geist M., Sfrontato N., Koerper V., Fahrner C., Schmitt D., Gantzer M., Remy-Ziller C., et al. Vectorization in an oncolytic vaccinia virus of an antibody, a Fab and a scFv against programmed cell death -1 (PD-1) allows their intratumoral delivery and an improved tumor-growth inhibition. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1220467. doi: 10.1080/2162402x.2016.1220467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Passaro C., Alayo Q., De Laura I., McNulty J., Grauwet K., Ito H., Bhaskaran V., Mineo M., Lawler S.E., Shah K., et al. Arming an oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 1 with a single-chain fragment variable antibody against PD-1 for experimental glioblastoma therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;25:290–299. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu Y., Hu X., Feng L., Yang Z., Zhou L., Duan X., Cheng S., Zhang W., Liu B., Zhang K. Enhanced therapeutic efficacy of a novel oncolytic herpes simplex virus type 2 encoding an antibody against programmed cell death 1. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2019;15:201–213. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engeland C.E., Grossardt C., Veinalde R., Bossow S., Lutz D., Kaufmann J.K., Shevchenko I., Umansky V., Nettelbeck D.M., Weichert W., et al. CTLA-4 and PD-L1 checkpoint blockade enhances oncolytic measles virus therapy. Mol. Ther. 2014;22:1949–1959. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krysko D.V., Garg A.D., Kaczmarek A., Krysko O., Agostinis P., Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo J., Li Y., He Z., Zhang B., Li Y., Hu J., Han M., Xu Y., Li Y., Gu J., et al. Targeting endothelin receptors A and B attenuates the inflammatory response and improves locomotor function following spinal cord injury in mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014;34:74–82. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabinovich G.A., Gabrilovich D., Sotomayor E.M. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y., Chi Y., Tang X., Ertl H.C.J., Zhou D. Rapid, efficient, and modular generation of adenoviral vectors via isothermal assembly. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2016;113:162611–162618. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1626s113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fang J., Qian J.J., Yi S., Harding T.C., Tu G.H., VanRoey M., Jooss K. Stable antibody expression at therapeutic levels using the 2A peptide. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nbt1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed L.J.M.,H., Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Public Health. 1938;27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.