Abstract

A series of bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives carrying different aromatic substituents attached to both nitrogen atoms of the natural alkaloid were studied with double-stranded model DNAs (dsDNAs) to examine the binding properties and mechanism. Variable-temperature molecular recognition studies using UV–vis and fluorescence techniques revealed the thermodynamic parameters, ΔH, ΔS, and ΔG, showing that the tetrandrine derivatives exhibit high affinity toward dsDNA (K ≈ 105–107 M–1), particularly the bis(methyl)anthraquinone (BAqT) and bis(ethyl)indole compounds (BInT). Viscometry experiments, ethidium displacement assays, and molecular modeling studies enabled elucidation of the possible binding mode, indicating that the compounds exhibit a synergic interaction mode involving intercalation of one of the N-aryl substituents and interaction of the molecular skeleton in the major groove of the dsDNA. Cytotoxicity tests of the derivatives with tumor and nontumor cell lines demonstrated low cytotoxicity of these compounds, with the exception of the bis(methyl)pyrene (BPyrT) derivative, which is significantly more cytotoxic than the remaining derivatives, with IC50 values against the LS-180, A-549, and ARPE-19 cell lines that are similar to natural tetrandrine. Finally, complementary electrochemical characterization studies unveiled good electrochemical stability of the compounds.

1. Introduction

The natural alkaloid S,S-(+)-tetrandrine has been extensively studied due to its multiple pharmacological activities.1,2 Tetrandrine is a macrocyclic compound that can be functionalized to yield diverse derivatives with enhanced activity.3−6 So far, the alkaloid and some of its various derivatives have been evaluated as potential treatments for cancer, viral7 and bacterial infections,8 cardiovascular afflictions,9 pulmonary fibrosis,10,11 diabetes,12,13 and cognitive impairment.14 However, one of the main limitations of using tetrandrine as a drug is its poor solubility in water and the consequent low bioavailability.1,15 On the other hand, derivatization of tetrandrine has been almost exclusively on its aromatic rings,4,5,16−20 leaving the functionalization on the nitrogen atoms largely unexplored, a strategy that can improve solubility in water and simplify the synthesis.

Our research groups have previously reported on a series of cationic mono- and bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives containing up to two additional chiral centers. These compounds promote ester cleavage21 and bind substrates of biological importance such as nucleotides and double-stranded (ds) DNA through a combination of noncovalent interactions, including π-stacking.22−26 Recently, a bis(methyl)naphthyl tetrandrine derivative was shown to self-assemble into an organic supramolecular framework with extremely large spherical cavities,27 indicating that tetrandrine is a versatile scaffold molecule with several potential applications.

Selective recognition of nucleic acids remains a primary goal for diverse reasons, including the design of novel anticancer agents, antibiotics, and antiviral drugs and the intracellular detection of DNA and RNA. Specific strategies have been developed for this purpose, depending on the desired application. For instance, effective anticancer and antiviral agents contain, frequently, planar aromatic substituents that intercalate into the base pairs of dsDNA, inhibiting the replication enzyme topoisomerase II,28 among other effects. Other binding modes of small molecules to nucleic acids, such as groove binding29−31 or electrostatic interactions,32−34 can lead to other applications.

We hypothesize that tetrandrine fits into the major groove of dsDNA, and through the addition of substituents on the nitrogen atoms the resulting positive charges facilitate the recognition of nucleic acids by means of the phosphate backbone. Herein, we report on dsDNA binding studies of a series of cationic bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives. The substituents chosen for introduction into the alkaloid skeleton are polyaromatics commonly used for DNA intercalation and groove binding and allow evaluation of the effect of these units as well as the presence of heteroatoms. Spectrophotometric titrations, viscometry, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and molecular modeling studies were carried out to determine the binding mode of the tetrandrine derivatives to the double helix of model dsDNA. In addition, viability MTT assays and complementary cyclic voltammetry studies were performed to examine the effect of the substituents over the cytotoxicity and gain information for further modifications of natural tetrandrine that can facilitate the development of new treatments and even fluorescent dsDNA probes for microscopic analysis.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

The bis-N-substituted derivatives BBT, BNaphT, and BAqT were prepared in moderate to good yields as reported previously in the literature.22,24,27 In analogous manner, the novel tetrandrine salts BInT and BPyrT were synthesized by quaternization of the tertiary amine groups of the alkaloid with 3-(2-bromoethyl)indole and 1-(bromomethyl)pyrene, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of tetrandrine and the bis-N-substituted tetrandrine salts studied in this work. Note: The chirality of the stereogenic centers in the isolated stereoisomers is indicated as S and R.

The products were fully characterized by elemental analysis, IR, NMR spectroscopy (Figures S1–S3), and mass spectrometry. According to the 1H NMR spectra, BInT and BPyrT constitute single stereoisomers, showing a single set of signals for the hydrogen atoms (Figures S1 and S3). UV–vis absorption and emission spectra of each derivative can also be found in the Supporting Information (Figures S4 and S5). The emission spectra show the expected bands for the fluorophore substituents of the derivatives. An excimer band was not observed for the BPyrT derivative.

Additionally, BBT crystals suitable for single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis were grown. Crystallographic data are given in the Experimental Section, and perspective views of the molecular structure of BBT, the asymmetric unit, and the unit cell are shown in Figures 2 and S6. The incorporation of benzyl units on the nitrogen atoms of the alkaloid produced two new chiral centers. Considering the known configuration of the asymmetric carbons of natural tetrandrine enabled us to establish the configuration for the new chiral centers as R giving the SC,SC,RN,RN-tetrandrine derivative.

Figure 2.

Perspective view of the molecular structure of one of the four crystallographically independent molecules of BBT (without the Br– counterions) extracted from the asymmetric unit of its crystal structure (C210H227Br8N9O24). The chirality of the stereogenic centers in the isolated stereoisomer is indicated as S and R.

2.2. DNA Binding Studies

The chemical and structural characteristics of the five tetrandrine derivatives are appropriate for binding to dsDNA. To examine the DNA binding characteristics, spectrophotometric titrations, electrophoretic mobility shift assays, and viscometry experiments were performed along with molecular modeling studies on complexes formed with model DNA to elucidate possible binding modes.

2.2.1. Recognition Studies of dsDNA

Molecular recognition studies between the derivatives BNaphT, BAqT, BInT, and BPyrT (Figure 1) and oligonucleotide DNA-1 were carried out either by UV–vis or by fluorescence emission spectroscopy. This oligonucleotide was chosen to ensure a complete turn of the double helix while maintaining a simple system that includes all nitrogenous bases.

For all spectrophotometric titrations, the samples were dissolved in phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v) containing NaCl (0.01 M), adjusted to pH = 7.2. Only BPyrT was suitable for titrations using UV–vis absorption spectroscopy; meanwhile, the remaining three derivatives showed a significant increase of the baseline and broadened bands (Figure S7), which can be attributed to aggregation of the DNA–tetrandrine derivative complexes as a consequence of the high affinity, as evidenced by the titrations followed by fluorescence spectroscopy. It is noteworthy that fluorescence measurements allow detection at lower concentrations; therefore, aggregation was not observed for any of the titrations reported herein. In the UV–vis spectra of compound BPyrT, a bathochromic shift was observed upon DNA binding, as seen in Figure S8, with changes in λmax from 331 and 347 nm to 342 and 354 nm, respectively. This shift can be associated with π-stacking of the pyrene units with the DNA base pairs.

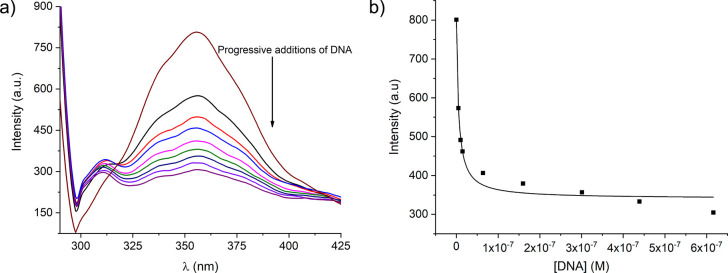

In a similar manner but using fluorescence spectroscopy, titrations of BNaphT, BAqT, and BInT with dsDNA were performed (Figures S9 and S10, Supporting Information), showing strong quenching of the fluorescence intensity for BInT, as seen in Figures 3 and S10, while for the case of BAqT, an increase in the emission of fluorescence intensity was observed (Figure S9). In the case of BNaphT, the experiments were not reproducible, which might be a consequence of the self-assembly characteristics of this compound as described previously.27

Figure 3.

Spectrophotometric titration of BInT. (a) Variation of the emission spectra for BInT (1.0 × 10–6 M) upon addition of DNA-1 (5 nM to 0.62 μM) at 25 °C in phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl, λexc = 280 nm. (b) Plot of the intensity of emissions at 356 nm of BInT versus the concentration of added DNA-1. The solid line is the fitting curve using the McGhee and von Hippel model. DNA-1, 5′-GTA AGA TGA TTC-3′ and 5′-GAA TCA TCT TAC-3′.

To gain better insight into the supramolecular interactions involved in the binding of the tetrandrine derivatives to dsDNA, the thermodynamic parameters ΔH and ΔS were calculated from the binding constants determined at different temperatures for the complexes with DNA-1, using the van’t Hoff equation (Table S1 and Figures S8–S11, Supporting Information). BPyrT and BInT gave favorable enthalpic and entropic contributions to the Gibbs free energy (Table 1). The negative ΔH values are attributed to intercalation into the base pairs of DNA,35 particularly by means of the pyrene and indole units, which are susceptible to π-stacking interactions. In addition, the rest of the molecule can establish electrostatic ion-pair interactions with the DNA phosphate backbones and van der Waals interactions with the major groove in the double helix. The binding of tetrandrine derivative cations is associated with the displacement of cations originally surrounding the phosphate backbone and a hydrophobic effect, with a consequent increase of the entropy in the system. Haq and Chaires have established that the binding of classical intercalators to dsDNA is enthalpically driven, while complexes with groove binders are entropically favored.35,36 For BAqT, the binding constants gave a nonlinear temperature dependence (Figure S11c), and hence, the thermodynamic parameters could not be calculated. A nonlinear van’t Hoff plot has been observed for heterogeneous systems as well as for systems involving significant protein conformational changes.37−39 The formation of BAqT–DNA-1 aggregates is probably more likely to occur since the oligonucleotide is not large enough to present major conformational changes.

Table 1. Binding Constants (Kb) at 25 °C and Thermodynamic Parameters for the Complexes Formed between DNA-1 and the Tetrandrine Derivatives Studied Hereina.

| derivative | Kb (M–1) | ΔH (J/mol) | ΔS (J/(mol K)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAqT | 1.85 × 107 ± 2.23 × 106b | c | c |

| BPyrT | 6.16 × 105 ± 6.42 × 104d | –23 865 | 30.7 |

| BInT | 9.53 × 107 ± 4.36 × 106b | –7464 | 127.7 |

DNA-1, 5′-GTA AGA TGA TTC-3′ and 5′-GAA TCA TCT TAC-3′.

Binding constants were determined by fluorescence.

Parameters could not be established due to a nonlinear temperature dependence of Kb.

Binding constant was determined by UV–vis.

2.2.2. Ethidium Bromide Displacement Assays

To further evaluate the binding phenomena of bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives with dsDNA, ethidium bromide displacement experiments were carried out, using oligonucleotides DNA-1, DNA-2, and DNA-3. Ethidium bromide displacement assays are generally accepted as an indirect method to identify intercalation in dsDNA. However, groove binders can displace ethidium bromide as well, and therefore, various experiments are needed to establish the definite mode of binding.37 The emission of the initial complex formed between dsDNA and ethidium bromide was quenched by all tetrandrine derivatives, revealing a particularly strong quenching in the case of BAqT. As an illustrative example, Figure 4 shows the results of the ethidium bromide displacement assays of BPyrT with the oligonucleotides constituted of adenine–thymine (DNA-2) or cytosine–guanine (DNA-3) nitrogenous bases; additional material is shown in Figures S12–S15. Table 2 summarizes the Stern–Volmer constants (KSV) obtained for the dsDNA complexes. As expected, the Stern–Volmer constants for complexes of DNA-1 are higher for all the tetrandrine derivatives compared to natural tetrandrine. Furthermore, in all derivatives, the Stern–Volmer constant was slightly larger for DNA-2 than for DNA-3, suggesting a small preference for oligonucleotides with adenine–thymine enriched sequences. In addition, ethidium bromide displacement experiments were performed with calf-thymus DNA (ctDNA) to ensure that the length of genomic DNA does not affect the magnitude of the interaction. For comparative purposes, the bis-substituted derivative with benzyl units (BBT), unable to intercalate, was included. Stern–Volmer constants with ctDNA are similar to the constants with oligonucleotides, as observed in Table S2.

Figure 4.

Emission spectra and their respective linear fittings (according to the Stern–Volmer equation) of the ethidium bromide displacement assays of BPyrT with two dsDNA sequences: (a) DNA-2, 5′-poly(A)18-3′ and 5′-poly(T)18-3′, and (b) DNA-3, 5′-poly(G)18-3′ and 5′-poly(C)18-3′. λexc = 510 nm, in phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl, at 25 °C. [EtBr] = 5 μM, [dsDNA] = 10 μM, [BPyrT] = 0–20 μM.

Table 2. Stern–Volmer Constants (KSV) for Complexes of Tetrandrine and Its Derivatives Studied Herein with DNA-1, DNA-2, and DNA-3a.

| compound | DNA-1 | DNA-2 | DNA-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| tetrandrine | 7.34 × 103 | b | b |

| BNaphT | 1.69 × 104 | 1.45 × 104 | 6.76 × 103 |

| BAqT | 1.33 × 105 | 5.17 × 104 | 1.53 × 104 |

| BPyrT | 4.84 × 104 | 1.34 × 104 | 8.26 × 103 |

| BInT | 2.72 × 104 | 2.32 × 104 | 1.08 × 104 |

DNA-1, 5′-GTA AGA TGA TTC-3′ and 5′-GAA TCA TCT TAC-3′; DNA-2, 5′-poly(A)18-3′ and 5′-poly(T)18-3′; DNA-3, 5′-poly(G)18-3′ and 5′-poly(C)18-3′. Complexes were formed in phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl, at 25 °C.

Not determined.

2.2.3. Electrophoretic Mobility Assays

As mentioned previously, BNaphT can self-assemble into spherical cages, a phenomenon documented by our group,27 which limits its solubility in aqueous medium. Even though this made quantification of the binding of BNaphT to dsDNA impossible by optical methods, a qualitative proof could be generated through an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. The mobility of a nucleic acid across the gel is decreased when bound to another molecule.38Figure 5 illustrates clearly that BNaphT and natural tetrandrine reduce the mobility of the plasmid. Although some migration is still observed, it can be inferred that both compounds bind to DNA. On the other hand, BPyrT and BInT seem to have a stronger interaction with DNA, as observed through spectrophotometric titrations, and prevent plasmid migration. Nicking of the plasmid was not observed. The BAqT–plasmid complex did not enter the pores of the agarose gel and, therefore, is not presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Electrophoresis mobility shift assays for (a) 100 ng of plasmid DNA and samples of plasmid DNA incubated for 2 h (b) with DMSO or with 0.1 nmol concentration of (c) tetrandrine, (d) BPyrT, (e) BNaphT, and (f) BInT.

2.2.4. Viscometry Experiments

In the absence of crystallographic data, viscometry is considered one of the most sensitive and reliable techniques to determine the binding mode of small molecules to DNA. Intercalation lengthens the DNA double strands and produces an increase in viscosity relative to uncomplexed DNA;39,40 meanwhile, groove binders do not alter the DNA length and viscosity. If the viscosity of DNA decreases, bending of the double strand is likely to have occurred.41 Calf thymus DNA (ctDNA) was chosen for viscometry experiments since the solutions of the previously used oligonucleotides were not suitable for the MicroUbbelohde viscometer; EtBr, a classic intercalator compound, was used as a control test.

BNaphT, BPyrT, and BInT decrease the viscosity of ctDNA indicating that the double strand is bent as a consequence of the supramolecular interactions with the tetrandrine derivatives (Figure 6). This is plausible when considering that one of the N-aryl substituents can intercalate into DNA, while the rest of the molecular skeleton interacts with the major groove. Such behavior can explain the strong entropic contribution to the binding of BPyrT and BInT (Table 1) with dsDNA and can be classified as a nonclassical intercalation. Finally, with BAqT the relative viscosity seems to remain unchanged; however, since only two concentrations of BAqT could be evaluated due to the low solubility at higher concentrations, the data points are insufficient to reach a conclusion in this case. Experiments such as dynamic light scattering could clarify whether BAqT–ctDNA complex aggregates result in the detected solubility limitations.

Figure 6.

Viscometry experiments for 100 μM calf-thymus DNA solutions in 0.0064 M phosphate buffer with 5% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl, using increasing concentrations of the tetrandrine derivatives studied herein or EtBr (10–40 μM) at 20 °C.

2.3. Molecular Modeling of the DNA–Tetrandrine Complexes

To get a better understanding of the complexes formed between DNA-1 (containing all nucleobases) and tetrandrine derivatives, molecular modeling studies were performed to propose a good representation of the binding mode of these complexes, based on the thermodynamic and viscometry binding studies. Figure S16 shows the geometry-optimized molecular gas phase structures of tetrandrine derivatives, while Figure 7 illustrates the lowest-energy structures of the complexes between DNA-1 and derivatives BInT and BPyrT (the remaining are shown in Figure S17), determined by molecular docking that was carried out using molecular mechanics (AMBER99 force field) and the HyperChem release 8.0 software.42

Figure 7.

Perspective views of modeled structures for the complexes formed between DNA-1 and the tetrandrine derivatives (a) BInT and (b) BPyrT.

In the calculated minimum-energy structures, one of the aromatic substituents of BInT and BPyrT is tightly bound through π-stacking among the base pairs, while the macrocycle skeleton is localized in the major groove, displaying a series of noncovalent contacts including electrostatic, van der Waals, and hydrophobic interactions. Of these, the electrostatic interactions are formed among positively charged nitrogen atoms of the BInT and BPyrT derivatives and negatively charged oxygen atoms at the phosphate backbones of the dsDNA. The short N+···O– distances of 3.87, 3.94, 3.64, and 4.69 Å for the case of DNA-1–BPyrT, as well as 3.78 and 4.24 Å for DNA-1–BInT, are typical for strong ion-pair interactions.25,26 Similar results were obtained for the calculated minimum-energy structure of DNA-1–BNaphT (Figure S17b), while the structure of DNA-1–BBT (Figure S17a) shows that BBT, unable to intercalate, is positioned in the major groove with short N+···O– distances.

Finally, a very interesting result was obtained for the minimum-energy structure of the complex formed between DNA-1 and BAqT. As shown in Figure S17c, the derivative has a very good fit within the major DNA groove without intercalation of any of the anthraquinones; other calculated structures showed at least partial intercalation of one anthraquinone although with higher energies.

The arrangements illustrated in Figures 7 and S17 are in good agreement with the data established from the experimental binding and viscometry studies, as well as with the depth, width, electrostatic potential, and steric effects of the DNA major groove. Generally, small molecules are localized in minor grooves, while larger molecules bind to the major groove even though it involves at least partial intercalation.43

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assays

Since DNA binding is usually linked to cytotoxicity, we evaluated the biological activity of the bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives studied herein, including BBT, and unmodified tetrandrine for comparison purposes, against the human cancer cell lines HeLa (cervical cancer), LS-180 (colon cancer), and A-549 (lung cancer), and the nontumor ARPE-19 (retinal epithelium) cell line.

As shown in Table 3, three of the derivatives revealed low cytotoxicity after 48 h of incubation. BPyrT, which carries the largest aromatic residues, is significantly more cytotoxic than the remaining derivatives, with IC50 values against the LS-180, A-549, and ARPE-19 cell lines that are comparable to those of natural tetrandrine. This effect is probably related to better intercalation as seen formerly for MAnT, a tetrandrine derivative substituted with one anthracene unit, previously reported by our group.26

Table 3. Cytotoxicity of the Bis-substituted Tetrandrine Derivatives Studied Herein against Human Cancer Cell Lines and Retinal Epithelium Cellsa.

| compound | HeLa | LS-180 | A-549 | ARPE-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetrandrine | 16.64 ± 0.02 (26.72 ± 0.03) | 6.43 ± 0.34 (10.33 ± 0.55) | 12.07 ± 1.51 (19.38 ± 2.42) | 8.45 ± 0.19 (13.57 ± 0.30) |

| BBT | >30.00* (>31.10) | >30.00* (>31.10) | >30.00* (>31.10) | >30.00* (>31.10) |

| BNaphT | >30.00* (>28.18) | >30.00* (>28.18) | 24.23 ± 0.29 (22.76 ± 0.27) | 21.10 ± 1.42 (19.82 ± 1.33) |

| BPyrT | >30.00* (>24.66) | 5.84 ± 0.72 (4.80 ± 0.59) | 17.47 ± 1.05 (14.36 ± 0.86) | 9.23 ± 1.97 (7.59 ± 1.62) |

| BInT | >30.00* (>28.02) | >30.00* (>28.02) | 28.25 ± 3.00 (26.39 ± 2.80) | 28.25 ± 1.49 (26.39 ± 1.39) |

| BAqT | >30.00* (>24.50) | >30.00* (>24.50) | >30.00* (>24.50) | >30.00* (>24.50) |

Data are shown as the mean IC50 ± SD (standard deviation) in μg/mL (μM ± SD in parentheses) from three independent repetitions after 48 h exposure to the test compounds. The asterisk (*) represents the maximum concentration tested, which did not reach an IC50 value.

Complementary electrochemical studies were performed to characterize the redox-active tetrandrine derivatives (Figure S18). The cyclic voltammograms of the tetrandrine derivatives with aryl substituents that do not possess heteroatoms, BNaphT and BPyrT, revealed each a single reduction and oxidation peak, with more negative E1/2 than BInT and BAqT. The peak current ratio (Ipa/Ipc) of the former approaches unity, indicating that the redox behavior is chemically reversible (Table S3). These parameters suggest that the derivatives described here do not possess any particular electrochemical properties indicating that they are oxidizing agents that could explain differences in cytotoxicity. Interestingly, and in contrast to tetrandrine, only low cytotoxicity was observed for BPyrT against HeLa, which deepens our drive to elucidate the underlying mechanisms to achieve specificity through proper selection of the substituents attached to the periphery of tetrandrine. Chemotherapeutic potential is generally valued for small molecules that bind to nucleic acids; however, the lack of relevant cytotoxicity of these tetrandrine derivatives could be an advantage if used as DNA probes.

3. Conclusions

The binding properties of a series of bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives were examined using various double-stranded DNA models. The molecular recognition studies and electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed that cationic tetrandrine derivatives functionalized with polyaromatic units have high affinity to dsDNA. Variations of the type of aryl substituents on the nitrogen atoms of the macrocyclic alkaloid allow the modulation of the physicochemical properties by varying the supramolecular interaction pattern and binding mode toward dsDNAs. These derivatives appear to bind to dsDNA through a dual binding mode involving partial intercalation of one substituent unit and accommodation of the remaining macrocycle skeleton in the major groove of the double helix.

While the presence of heteroatoms on the substituent increases the binding constant to dsDNA, it does not necessarily result in higher cytotoxicity. As a matter of fact, viability MTT assays against tumor and nontumor cell lines revealed that these compounds have low cytotoxicity. In contrast, the derivatives with naphthyl and particularly the compound with pyrenyl units are promising anticancer drugs and are currently being studied as antimicrobial agents. The explanation seems to rely on the better ability to intercalate naphthalene and pyrene, a property that has been linked to cytotoxicity.

Even though complementary electrochemical characterization studies did not offer significant insight on the possible mechanism of the cytotoxicity observed for BPyrT, they revealed good stability of the derivatives that could be useful for exploration as dsDNA fluorescent probes. We are currently conducting fluorescence studies at excitation wavelengths suitable for confocal microscopy of the tetrandrine derivatives in order to assess a potential application in this direction. Finally, we consider that the ionic nature of the N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives can improve the solubility of the alkaloid, one of the main limitations in the application of tetrandrine, and aggregates by self-assembling are not formed in most cases. However, these characteristics strongly depend on the chemical nature of the incorporated substituent.

4. Experimental Methods

4.1. General Procedures and Materials

4.1.1. Reagents

All reagents (including natural tetrandrine) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Desalted oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. All solutions were prepared in deionized water from a Milli-Q Advantage A10 Water Purification System with a conductivity below 18 mΩ.

4.1.2. Instruments

NMR studies were carried out with a Bruker Avance III 400 spectrometer, using TMS as reference (δ 1H = 0). Mass spectra were recorded on an Agilent 6100 LC/MS instrument using the ESI+ mode. UV–vis and fluorescence spectra were performed on Agilent 8435 diode array and PerkinElmer LS50B equipment using quartz cells of 1 cm optical path. The cuvettes were thermostatted at 25 °C through circulating water with a Thermo Scientific SC100 Circulating Bath. Melting points were recorded on a Büchi melting point B-545 instrument.

4.2. Preparation of Tetrandrine Derivatives

Bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives BBT, BNaphT, and BAqT were prepared following the synthetic procedures reported previously.22,24,27 The syntheses of the novel compounds BInT and BPyrT are described below.

4.2.1. Synthesis of BInT (C58H62Br2N4O6)

S,S-(+)-Tetrandrine (0.180 g, 0.289 mmol) and 3-(2′-bromoethyl)indole (0.136 g, 0.606 mmol) were refluxed and stirred during 48 h in acetone (60 mL). The reaction was monitored by TLC until all tetrandrine was consumed. The resulting reaction mixture in the form of a suspension was rota-evaporated until dryness, whereupon ethyl acetate was added. A precipitate formed and was washed with the same solvent, filtered, and dried under vacuum to yield the product as a colorless solid (0.29 g, yield 93.5%). Decomposition point: 219–222 °C. UV absorption (DMSO/water, 10:90 v/v), λ (nm), ε (dm3 mol–1 cm–1): λ240, ε = 18435; λ280, ε = 15925.

Despite the large number of hydrogen atoms, the 1H NMR spectra showed characteristic signals that could be assigned using two-dimensional experiments. The signals for the two N-CH3 and four O-CH3 groups were found at δH = 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.68 (s, 3H), 3.57 (s, 3H), 3.10 (s, 3H), 2.63 (s, 3H), and 2.56 (s, 3H) ppm. The signals at δH = 5.13 (m, 2H), 4.74 (m, 2H), and 4.27 (m, 4H) were assigned to the N+-CH2 and N+-CHR hydrogen atoms. The ten aromatic hydrogen atoms of the tetrandrine macrocycle and the ten aromatic hydrogen atoms of the two indole units are found in the region of δH = 7.72–6.17 (m, 20H). Finally, the indole NH-group gave a characteristic single signal at δH = 10.97 (s, 2H). MS-ESI(+) m/z: 455.3 ([BInT – 2Br–]2+, 100%). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C58H62Br2N4O6·3.5H2O: C, 61.43; H, 6.13; N, 4.94. Found: C, 61.44; H, 5.24; N, 4.35.

4.2.2. Synthesis of BPyrT (C72H64Br2N2O6)

S,S-(+)-Tetrandrine (0.180 g, 0.289 mmol) and 1-(bromomethyl)pyrene (0.213 g, 0.722 mmol) were refluxed and stirred for 24 h in 60 mL of acetone/chloroform (1:1 v/v). The reaction mixture was filtered and rota-evaporated until dryness, whereupon acetone was added. The precipitate was washed with acetone, separated by filtration, and dried under vacuum to yield the product as colorless solid (0.150 g, yield: 43%). Decomposition point: 203–207 °C. UV absorption (DMSO/water, 10:90 v/v), λ (nm), ε (dm3 mol–1 cm–1): λ244, ε = 80808; λ279, ε = 43642; λ331, ε = 34980; λ347, ε = 48244.

Despite the large number of hydrogen atoms, the 1H NMR spectra showed characteristic signals that could be assigned using two-dimensional experiments. The signals for the N-CH3 and O-CH3 groups were found at δH = 3.86 (s, 3H), 3.63 (s, 3H), 3.59 (s, 3H), 3.52 (s, 3H), 2.87 (s, 3H), and 2.45 (s, 3H) ppm. The signals at δH = 5.59 (m, 1H), 5.64–5.53 (m, 2H), 5.43–5.27 (m, 2H), 5.09–5.00 (m, 2H), and 4.68–4.32 (m, 3H) were assigned to the N+-CH2 and N+-CHR hydrogen atoms. The ten hydrogen atoms of the aromatic skeleton of tetrandrine were found at δH = 7.51 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (s, 1H), 6.88 (m, 2H), 6.81 (m, 1H), 6.55 (d, J = 10.2 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (s, 1H), and 6.24 (s, 1H) ppm. Finally, the hydrogen atoms of the pyrene units gave a series of signals in the range from 8.0 to 9.0 ppm that integrate for 18 hydrogen atoms. MS-ESI(+) m/z: 526.5 ([BPyrT – 2Br–]2+, 100%). Elem. Anal. Calcd for C72H64Br2N2O6·4H2O: C, 67.29; H, 5.65; N, 2.18. Found: C, 67.08; H, 4.87; N, 1.84.

4.3. Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Analysis

Single crystals of BBT (Figure 1) were grown by slow solvent evaporation from solution in acetonitrile at room temperature. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected at T = 100 K on an Agilent Technologies SuperNova diffractometer equipped with a CCD area detector (EosS2) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) from a microfocus X-ray source and an Oxford Instruments Cryojet cooler. The measured intensities were reduced to F2 and corrected for absorption using spherical harmonics (CryAlisPro).44 Intensities were corrected for Lorentz and polarization effects. Structure solution, refinement, and data output were performed with the OLEX245 program package using SHELXL-201446 for the refinement. Non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. All hydrogen atoms were placed in geometrically calculated positions using the riding model.

The asymmetric unit comprises four crystallographically independent molecules of BBT. A total of eight peaks were localized close to the ammonium nitrogen atoms in difference Fourier maps and assigned to the bromine counterions. Besides the atoms corresponding to the molecular structure of BBT, a large number of additional peaks were detected, several of which indicated the presence of acetonitrile. However, least-squares refinement showed relatively large thermal displacement values for all solvent molecules except for one, indicating disorder. Because of this, in the final stage of the refinement the SOLVENT MASK methodology47 implemented in OLEX45 was used to achieve the final data set. Analysis of the solvent accessible volume gave a total of 6593.2 Å3 corresponding to 28.6% of the unit cell volume (electron count = 806). Figures have been created with Diamond.48 Selected crystallographic data for BBT are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Selected Crystallographic Data for BBT.

| formula | C210H227Br8N9O24 |

| MW (g mol–1) | 3900.27 |

| space group | P212121 |

| T (K) | 100.0(3) |

| a (Å) | 24.27507(18) |

| b (Å) | 28.6715(2) |

| c (Å) | 33.1633(3) |

| V (Å3) | 23081.8(3) |

| Z | 4 |

| μ (mm–1) | 2.119 |

| Ra | 0.0681 |

| Rwb | 0.1868 |

| GOF | 1.033 |

| Flack parameter | 0.007(5) |

I > 2σ(I); R = ∑||F0| – |Fc||/∑|F0|.

All data; Rw = [∑w(Fo2 – Fc2)2/∑w(Fo2)2]1/2.

Crystallographic data for the crystal structure have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary publication no. 2123405. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK (fax (+44)1223-336-033; e-mail deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk; http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

4.4. Spectrophotometric Titrations

Prior to the titration experiments, the molar absorptivities were obtained at the absorption maximum of the spectrum of each tetrandrine derivative (Figure S4), ensuring a linear concentration dependence of the absorbance. The fluorescence spectra of the derivatives (Figure S5) are in agreement with the known spectral characteristics of each of the fluorophore units.

Spectrophotometric titrations were performed with 10–6 to 10–5 M solutions of the corresponding tetrandrine derivative dissolved in 0.0064 M phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl. There was no visible aggregation under such conditions, and the chosen concentration for the titration of any derivative falls in the linear response of the observed property. For the recognition experiments with the double-stranded DNA models, the respective oligomer was mixed in the same medium with its complementary sequence and heated for 5 min to 98 °C in a Thermo Scientific dry bath/block heater, followed by slow cooling to room temperature. The following dsDNA sequences were used: DNA-1, 5′-GTA AGA TGA TTC-3′ and 5′-GAA TCA TCT TAC-3′; DNA-2, 5′-poly(A)18-3′ and 5′-poly(T)18-3′; DNA-3, 5′-poly(G)18-3′ and 5′-poly(C)18-3′.

Binding constants for the complexes formed between the tetrandrine derivatives and the model dsDNA were obtained by recording changes of the absorption or emission spectrum of a fixed amount of the tetrandrine derivative dependent on increasing concentrations of added dsDNA. All UV–vis and fluorescence spectrometric titration curves were fitted with the Microcal OriginPro8 software package using the following equation, which here is expressed in terms of absorbance and is analogous for emission intensity:49

where Aobs is the observed absorbance, A0 is the initial absorbance, A∞ is the maximum absorbance change, Kb is the binding constant, and [L]t is the total concentration of ligand, in this case dsDNA. The nonlinear curve fitting of the data was compared with the classical Scatchard linear plot, which is commonly used in dsDNA binding studies in combination with the McGhee and von Hippel equation.26 As expected, the same results were obtained without dependence on the fitting model employed.

4.5. Ethidium Bromide Displacement Assays

For the ethidium bromide (EtBr) displacement assays, increasing amounts of a tetrandrine derivative stock solution were added to a solution of the dsDNA–EtBr complex ([DNA] = 10 μM and [EtBr] = 5 μM) in 0.0064 M phosphate buffer with 10% DMSO (v/v), pH = 7.2, 0.01 M NaCl. The fluorescence spectra of EtBr bound to dsDNA were measured using an excitation wavelength of 510 nm. The resulting titration data were plotted according to the Stern–Volmer equation to obtain the quenching constant, KSV.39

where I0 and I are the emission intensities of the dsDNA–EtBr complex in the absence and in the presence of quencher (Q), respectively. KSV corresponds to the slope obtained from the plot of I/I0 versus [Q].

4.6. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

Samples of plasmid DNA pCR 2.1 (100 ng, Thermo Scientific) containing a cloned DNA sequence of a total of 4.5 kb were combined with 0.1 nmol of the respective tetrandrine derivative in a solvent mixture of DMSO and deionized water 10:90 (v/v) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The samples were loaded into 1% agarose gel, and their electrophoretic mobility was examined after electrophoresis for 30 min at 60 V. After staining the gel under gentle agitation for 5 min with ethidium bromide (5 μg/mL), the samples were washed with water for 2 h, and then revealed with UV-light using a Gel Doc EZ documentation system from Bio-Rad.50 The solvent mixture and a solution of plasmid only were used as controls.

4.7. Viscometry Measurements

Viscosity studies of complexes formed between the tetrandrine derivatives and calf thymus DNA (ctDNA) were carried out with a MicroUbbelohde viscometer from SI Analytics at a temperature of 20 °C, which was maintained with a PolyScience temperature controller. Ethidium bromide (EtBr), which is a classic intercalator compound, was used as a control test. For the experiment, the flow time of calf thymus DNA (ctDNA) was measured upon addition of the tetrandrine derivative. Each data point was established from ten measurements using a digital stopwatch. The relative viscosity of the ctDNA solution (η0) and the tetrandrine–ctDNA complexes (η) were calculated according to the equation:

where t is the average flow time of the respective solution and t0 is the average flow time of the medium (phosphate buffer with 5% DMSO v/v). The results were plotted as (η/η0)1/3 against the [tetrandrine derivative]/[ctDNA] ratio.51

4.8. Molecular Modeling

For the molecular modeling studies of the tetrandrine derivatives, the initial molecular structures were constructed by using the X-ray diffraction coordinates of BBT and those previously reported for BNaphT27 for the macrocycle skeleton, attaching when necessary the respective N-CH2-aryl substituents using the Avogadro software tool.52 The tetrandrine derivatives were then geometry-optimized in the gas phase by using the PM6 semiempirical method implemented in the Gaussian 09 program package.53 The structure of double-stranded B DNA-1 was generated from the nucleic acid database of HyperChem release 8.0 software42 and optimized in the gas phase by applying the AMBER99 force field and a Polak–Ribiere conjugate algorithm with a convergence criterion of 0.001 kcal/(Å mol). For the molecular modeling of the DNA–tetrandrine derivative complexes, the optimized conformer of the tetrandrine derivative was manually docked with DNA-1 based on the findings obtained from the titration and viscometry studies. Geometry optimizations of the complexes with DNA were carried out using molecular mechanics (AMBER99 force field) and the HyperChem release 8.0 software.42

4.9. Cytotoxicity Assays

Cytotoxicity study tests of the bis-N-substituted tetrandrine derivatives studied herein were performed through MTT assays on the human cancer cell lines HeLa (cervical cancer), LS-180 (colon cancer), and A-549 (lung cancer). For comparison, the nontumoral cell line ARPE-19 (retinal epithelium) was also included. The cells were initially cultured in a 96-well sterile plate with DMEM medium supplemented with 5% FBS at a density of 10000 cells per well. Different concentrations of the tetrandrine derivatives were added, followed by 48 h incubation. After that time, 10 μM MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] dissolved in DMSO was added to each well followed by incubation for 4 h at 37 °C. Acidic isopropanol was added under stirring to dissolve formazan crystals, and after 10 min, the plate was analyzed in a Bio-Rad ELISA plate reader, with 570 nm being the test wavelength and 630 nm the reference wavelength. Control experiments were performed in parallel. Cytotoxicity was reported as the 50% inhibitory concentration, IC50.54 All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

The data are reported as mean IC50 ± SD (standard deviation) and were subjected to statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA), comparing the mean values with the Tukey test (p < 0.05). For the statistical analyses, the IBM* SPSS* 20 Program was used.

4.10. Cyclic Voltammetry Studies

Cyclic voltammograms (CV) were recorded at room temperature in a conventional three-electrode cell, using a platinum wire as the auxiliary electrode and Ag/AgCl (KBr, 3 M) as reference electrode. Measurements were performed in DMSO solutions containing 0.20 M tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (NBu4PF6) as supporting electrolyte, using a Metrohm PGSTAT 128N equipment. Previously, the working electrodes were prepared by evaporating a drop (5.0 μL) of a suspension of the corresponding tetrandrine derivative in acetonitrile (1 mg/mL) located on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE, BAS MF 4012, exposure area 0.071 cm2). CVs were collected with scan rates of 100 mV/s with iR compensation.55

Acknowledgments

This work received financial support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología Mexico in the form of graduate grants for S.G.M. and V.C.P. and through project Nos. CB-239581 and 281251 (Red Temática de Química Supramolecular). M.A.I.O. thanks Universidad de Sonora for the sabbatical leave support. D.P.V. received financial support from OMICAS program, sponsored within the Colombian Scientific Ecosystem by The World Bank, The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MINCIENCIAS), ICETEX, the Colombian Ministry of Education, and the Colombian Ministry of Industry and Tourism under Grant ID FP44842-217-2018.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00225.

NMR spectra of BInT and BPyrT, UV–visible absorption and emission spectra of BNaphT, BPyrT, BAqT, and BInT, perspective views of the asymmetric unit and the unit cell of BBT, spectroscopic titrations and fitting curves for all derivatives, as well as Stern–Volmer constants, and binding constants for BPyrT, BAqT, and BInT at different temperatures with corresponding van’t Hoff plots, geometry-optimized molecular gas phase structures of BBT, BNaphT, BPyrT, BAqT, and BInT, lowest-energy structures of the complexes between DNA-1 and derivatives BBT, BNaphT, and BAqT, and cyclic voltammograms and electrochemical parameters of BNaphT, BPyrT, BAqT, and BInT (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bhagya N.; Chandrashekar K. R. Tetrandrine – A molecule of wide bioactivity. Phytochemistry 2016, 125, 5–13. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.; Liu X.; Li W. Tetrandrine, a Chinese plant-derived alkaloid, is a potential candidate for cancer chemotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 40800–40815. 10.18632/oncotarget.8315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei N.; Sun H.; Wang F.; Liu G. H. A novel derivative of tetrandrine reverse P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by inhibiting transport function and expression of P-glycoprotein. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 1017–1025. 10.1007/s00280-010-1397-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J.; Wang N.; Huang L.; Liu Y.; Ma X.; Lou H.; Chen C.; Feng Y.; Pan W. Design and synthesis of novel tetrandrine derivatives as potential anti-tumor agents against human hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 127, 554–566. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Lan J.; Chen C.; Hu S.; Song J.; Liu W.; Zeng X.; Lou H.; Ben-David Y.; Pan W. Design, synthesis and bioactivity investigation of tetrandrine derivatives as potential anti-cancer agents. Med. Chem. Commun. 2018, 9, 1131–1141. 10.1039/C8MD00125A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.; Li D.; Liu L.; Yang P. Effect of five novel 5-substituted tetrandrine derivatives on P-glycoprotein-mediated inhibition and transport in Caco-2 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 6808–6814. 10.3892/ol.2018.9492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. E.; Min J. S.; Jang M. S.; Lee J. Y.; Shin Y. S.; Park C. M.; Song J. H.; Kim H. R.; Kim S.; Jin Y.-H.; Kwon S. Natural Bis-Benzylisoquinoline Alkaloids-Tetrandrine, Fangchinoline, and Cepharanthine, Inhibit Human Coronavirus OC43 Infection of MRC-5 Human Lung Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 696–712. 10.3390/biom9110696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.-S.; Han S.-H.; Lee S.-H.; Kim Y.-G.; Park C.-B.; Kang O.-H.; Keum J.-H.; Kim S.-B.; Mun S.-H.; Seo Y.-S.; Myung N.-Y.; Kwon D.-Y. The Mechanism of Antibacterial Activity of Tetrandrine Against Staphylococcus aureus. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9 (8), 686–691. 10.1089/fpd.2011.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Li W.-R.; Jin Y.-G.; Jie Q.-Q.; Wang C.-Y.; Wu L. Tetrandrine Attenuated Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiac Injury in Mice. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 8, 2616024. 10.1155/2020/2616024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M. Y.; Wang J. X.; Sun Y. L.; Han Z. F.; Zhou Y. T.; Liu Y.; Fan T. H.; Li Z. G.; Qi X. M.; Luo Y.; Yang P. R.; Li B. C.; Zhang X. R.; Wang J.; Wang C. Tetrandrine alleviates silicosis by inhibiting canonical and non-canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation in lung macrophages. Acta Pharmacol. Sin 2021, 10.1038/s41401-021-00693-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W.; Liang Y.; Meng Z.; Chen X.; Lu M.; Han X.; Deng X.; Zhang Q.; Zhu H.; Fu T. Inhalation of Tetrandrine-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes for Pulmonary Fibrosis Treatment. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2020, 17, 1596–1607. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L.; Cao P.; Wang H. Tetrandrine mediates renal function and redox homeostasis in a streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy rat model through Nrf2/HO-1 reactivation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 990–1002. 10.21037/atm-20-5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman I.; Lentz D. P.; Trucco G. A.; Seow W. K.; Thong Y. H. Prevention by Tetrandrine of Spontaneous Development of Diabetes Mellitus in BB Rats. Diabetes 1992, 41, 616–619. 10.2337/diab.41.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H.; Yao L.; Pang L.; Li X.; Yao Q. Tetrandrine ameliorates sevoflurane-induced cognitive impairment via the suppression of inflammation and apoptosis in aged rats. Molecular Medicine Reports 2016, 13, 4814–4820. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C.; Khan S. A.; Wang K.; Schneider M. Improved delivery of the natural anticancer drug tetrandrine. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 479, 41–51. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.; Lu Y. Tetrandrine derivatives IVa-IVd: Structural analysis and their inhibition rate against protein tyrosine kinase, and HL60 & A549 cancer cell lines. Indian J. Chem. 2020, 59A, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.-H.; Wang S.; Zhang H.; Lan J.-J.; Xu G.-B.; Zhao Y.-L.; Wang L.; Li Y.-J.; Wang Y.-L.; Zhou Y.-H.; Liu J.-L.; Pan W.-D.; Liao S.-G.; Zhou M. Discovery of tetrandrine derivatives as tumor migration, invasion and angiogenesis inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 101, 104025. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu N.; Jin T.; Li X.; Xu J.; Qu T.; Bodwell G. J.; Zhao Z. Design and Synthesis of Tetrandrine Derivatives as Potential Anti-tumor Agents Against A549 Cell Lines. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 196–201. 10.1002/slct.201803592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.-H.; Jiang C.-S.; Jin T.; Xu J.-F.; Qu T.-L.; Guo Y.-W.; Zhao Z.-B. Synthesis of novel tetrandrine derivatives and their inhibition against NSCLC A549 cells. JANPR 2018, 20, 1064–1074. 10.1080/10286020.2018.1478817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He P.; Sun H.; Jian X.-X.; Chen Q.-H.; Chen D.-L.; Liu G.; Wang F.-P. Partial synthesis and biological evaluation of bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids derivatives: potential modulators of multidrug resistance in cancer. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 14, 564–576. 10.1080/10286020.2012.680443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa Lara K.; Godoy-Alcántar C.; Eliseev A. V.; Yatsimirsky A. K. Ester cleavage by S, S-(+)-tetrandrine derivative bearing thiol groups. ARKIVOC 2005, 293–306. 10.3998/ark.5550190.0006.625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa Lara K.; Godoy-Alcántar C.; León Rivera I.; Eliseev A. V.; Yatsimirsky A. K. Complexation of dicarboxylates and phosphates by a semisynthetic alkaloid-based cyclophane in water. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2001, 14, 453–462. 10.1002/poc.387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa Lara K.; Godoy-Alcántar C.; Eliseev A. V.; Yatsimirsky A. K. Recognition of n-amino acid derivatives by N, N′-dibenzylated S, S-(+)-tetrandrine. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 1712–1718. 10.1039/B402698E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Corral R.; Ochoa Lara K. Complexation Studies of Nucleotides by Tetrandrine Derivatives Bearing Anthraquinone and Acridine Groups. Supramol. Chem. 2008, 20, 427–435. 10.1080/10610270701300188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Molina A.; Lara K. O.; Sánchez M.; Burboa M. G.; Gutiérrez-Millán L. E.; Marín J. L.; Valdez M. A. Interaction of Calf Thymus DNA with a Cationic Tetrandrine Derivative at the Air–Water Interface. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2008, 4, 52–61. 10.1166/jbn.2008.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo-Páez V.; Sotelo-Mundo R. R.; Leyva-Peralta M.; Gálvez-Ruiz J. C.; Corona-Martínez D.; Moreno-Corral R.; Escobar-Picos R.; Höpfl H.; Juárez-Sánchez O.; Ochoa Lara K. Synthesis, spectroscopic, physicochemical and structural characterization of tetrandrine-based macrocycles functionalized with acridine and anthracene groups: DNA binding and anti-proliferative activity. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 286, 34–44. 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Picos R.; Vasquez-Ríos M. G.; Sotelo-Mundo R. R.; Jancik V.; Martínez-Otero D.; Calvillo-Páez V.; Höpfl H.; Ochoa Lara K. A Chiral Bis-Naphthylated Tetrandrine Dibromide: Synthesis, Self-Assembly into an Organic Framework Based On Nanosized Spherical Cages, and Inclusion Studies. ChemPlusChem. 2019, 84, 1140–1144. 10.1002/cplu.201900344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A.; Lavery R.; Bagchi B.; Hynes J. T. On the molecular mechanism of drug intercalation into DNA: a simulation study of the intercalation pathway, free energy, and DNA structural changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9747–9755. 10.1021/ja8001666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskatov J. A.; Meier J. L.; Puckett J. W.; Yang F.; Ramakrishnan P.; Dervan P. B. Modulation of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription using programmable DNA minor groove binders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 1023–1028. 10.1073/pnas.1118506109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidwell R. R.; Boykin D. W.. Dicationic DNA Minor Groove Binders as Antimicrobial Agents. In Small Molecule DNA and RNA Binders: From Synthesis to Nucleic Acid Complexes, 1st ed.; Demeunynck M., Bailly C., Wilson W. D., Eds.; WILEY-VCH, 2003; pp 414–460. [Google Scholar]

- Paul A.; Guo P.; Boykin D. W.; Wilson W. D. A New Generation of Minor-Groove-Binding—Heterocyclic Diamidines That Recognize GHC Base Pairs in an AT Sequence Context. Molecules 2019, 24, 946–968. 10.3390/molecules24050946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasundaram D.; Tyagi A. K. Polyamine — DNA nexus: structural ramifications and biological implications. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1991, 100, 129–140. 10.1007/BF00234162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran S.; Thomas T.; Thomas T. J.. Role of Polyamines in Regulation of Sequence-Specific DNA Binding Activity. In Polyamine Cell Signaling, 1st ed.; Wang J. Y., Casero R. A., Eds.; Humana Press, 2006; pp 91–122. [Google Scholar]

- Iacomino G.; Picariello G.; D’Agostino L. DNA and nuclear aggregates of polyamines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1823, 1745–1755. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaires J. A. Thermodynamic signature for drug–DNA binding mode. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2006, 453, 26–31. 10.1016/j.abb.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq I. Thermodynamics of drug–DNA interactions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002, 403, 1–15. 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A.; Singh J.; Dasgupta D. Fluorescence Spectroscopic and Calorimetry Based Approaches to Characterize the Mode of Interaction of Small Molecules with DNA. J. Fluoresc. 2013, 23, 745–752. 10.1007/s10895-013-1211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutts S. M.; Masta A.; Panousis C.; Parsons P. G.; Sturm R. A.; Phillips D. R.. A Gel Mobility Shift Assay for Probing the Effect of Drug–DNA Adducts on DNA-Binding Proteins. In Methods in Molecular Biology, 1st ed.; Fox K. R., Ed.; Humana Press, 1997; pp 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz J. R.Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Suh D.; Chaires J. Criteria for the Mode of Binding of DNA Binding Agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1995, 3, 723–728. 10.1016/0968-0896(95)00053-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkhudaryan V. G.; Ananyan G. V.; Dalyan Y. B.; Haroutiunian S. G. Development of viscometric methods for studying the interaction of various porphyrins with DNA. Part I: meso-tetra-(4N-hydroxyethylpyridyl) porphyrin and its Ni-, Cu-, Co- and Zn- containing derivatives. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2014, 18, 594–599. 10.1142/S1088424614500357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HyperChem, release 8.0 software; Hypercube, Inc., 2007.

- Gonzalez-Garcia J.; Vilar R.. Supramolecular Principles for Small Molecule Binding to DNA Structures. In Comprehensive Supramolecular Chemistry II, 2nd ed.; Atwood J. L., Ed.; Elsevier Science, 2017; Vol. 4, pp 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- Agilent Technologies . CrysAlisPro, version 1.171.37.35. Yarnton, Oxfordshire, United Kindom, 2014.

- Dolomanov O. V.; Bourhis L. J.; Gildea R. J.; Howard J. A. K.; Puschmann H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. 10.1107/S0021889808042726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. 2015, C71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees B.; Jenner L.; Yusupov M. Bulk-solvent correction in large macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr. 2005, D61, 1299–1301. 10.1107/S0907444905019591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz H.; Brandenburg K.. Diamond - Crystal and Molecular Structure Visualization, GbR, Kreuzherrenstr. 102, 53227 Bonn, Germany.

- Schneider H.-J.; Yatsimirsky A. K.. Energetics of supramolecular complexes: Experimental Methods. Principles and Methods in Supramolecular Chemistry, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2000; pp 137–226. [Google Scholar]

- Patel M. N.; Chhasatia M. R.; Patel S. H.; Bariya H. S.; Thakkar V. R. DNA cleavage, binding and intercalation studies of drug-based oxovanadium(IV) complexes. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24, 715–721. 10.1080/14756360802361423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G.; Eisenberg H. Viscosity and sedimentation study of sonicated DNA–proflavine complexes. Biopolymers 1969, 8, 45–55. 10.1002/bip.1969.360080105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanwell M. D.; Curtis D. E.; Lonie D. C.; Vandermeersch T.; Zurek E.; Hutchison G. R. Avogadro: An advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. J. Cheminform. 2012, 4, 17. 10.1186/1758-2946-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, revision A.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Meth. 1983, 65, 55–63. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard A. J.; Faulkner L. R.. Electrochemical methods: Fundamentals and applications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.