Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus 2 (CoV-2) variant Omicron spread more rapid than the other variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Mutations on the Spike (S) protein receptor-binding domain (RBD) are critical for the antibody resistance and infectivity of the SARS-CoV-2 variants. In this study, we have used accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) simulations and free energy calculations to present a systematic analysis of the affinity and conformational dynamics along with the interactions that drive the binding between Spike protein RBD and human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. We evaluate the impacts of the key mutation that occur in the RBDs Omicron and other variants in the binding with the human ACE2 receptor. The results show that S protein Omicron has stronger binding to the ACE2 than other variants. The evaluation of the decomposition energy per residue shows the mutations N440K, T478K, Q493R and Q498R observed in Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 provided a stabilization effect for the interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 RBD and ACE2. Overall, the results demonstrate that faster spreading of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron may be correlated with binding affinity of S protein RBD to ACE2 and mutations of uncharged residues to positively charged residues such as Lys and Arg in key positions in the RBD.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Proteins, Biophysics, Computational biophysics, Protein analysis, Computational chemistry, Molecular dynamics

Introduction

First reported in the city of Wuhan, China1,2, Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) named by World Health Organization (WHO) was declared a global pandemic on March 20203. COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)1,2,4,5. The spread of SARS-CoV-2 have cost millions of lives and caused many implications for health, society and the economy6,7. In January 2022, the WHO reported over 304 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and over 5.4 million fatalities have been reported since the beginning of the outbreak8. Vaccines are effective for reducing the number deaths by COVID-199–11. On the other hand, variants may cause impact on the virus recognition by antibody-mediated vaccines12–14.

Different mutations have been reported in the gene encoding the S protein of SARS-CoV-215,16, and recently, the world have faced rapid increase in COVID-19 mediated by new variants17. The last variant detected was named Omicron (B.1.1.529)18, identified in numerous countries in November 2021, first reported in South African with a large number of mutations, including K417N, S477N, T478K, E484A, and N501Y, which are also found in other variants19–21 and evidences suggests there may be an increased risk of reinfection involving this variant22,23 due to improve viral escape or binding affinity to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)24–26.

A recent study reported that 45 point mutations was identified and found that the Omicron Spike protein sequence was subjected to stronger positive selection than that of any reported SARS-CoV-2 variants27. Additionally, These mutations and deletions in the S-protein sequence can alter the structure, affecting its stability and function, further exacerbating SARS-CoV-2 infectivity16,28. However, N501Y mutation is a key contact residue in the receptor-binding domain (RBD), enhancing virus binding affinity to ACE229–31 making the virus more contagious and the deletions H69/V70 is required for increase optimal infectivity of Alpha variant, that drives by higher levels of Spike incorporation into virions32.

Coronaviruses use Spike (S) glycoprotein, with S1 subunit and S2 subunit in each Spike monomer, anchored in the virion envelope to bind to their cellular receptors33,34 and mediates the recognition of the host-cell receptors and facilitates the cell attachment (S1 subunit) and the cell membrane fusion (S2 subunit) during the viral infection35. The RBD located in the S1 region (318–510 sequence region) performs strongly binds to the peptidase domain of ACE236,37, leading to a critical virus-receptor interaction and reflects viral host range, tropism and infectivity38. The RBD of S1 undergoes conformational changes that transiently conceal or reveal the determinants of receptor binding24,39.

The Spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV-2 consists in an extracellular N-terminus, a transmembrane (TM) domain and a intracellular C-terminal segment40. S protein has a total length of 1273 amino acids35 and molecular weight of 180–200 kDa41. It has a signal peptide (1–13) at the N-terminus, followed by S1 subunit (14–685) and the S2 subunit (686–1273)35. The structure of the RBD allows for ways to alter its genetic material, developing variants by the changes in Spike protein amino acids and as viruses replicate16, copying errors of itself, resulting in mutations that arise in their genomes generating several strains of SARS-CoV-217,42 that differ in transmission, infectivity and severity of the disease42.

ACE2 primary physiological role is in the maturation of angiotensin (Ang)43, a peptide hormone that controls vasoconstriction and blood pressure, is a type I membrane protein expressed in lungs, heart, kidneys, and intestine25,44, thereat, decreased expression of ACE2 is associated with cardiovascular diseases45. The structural features of RBD increase its binding affinity to the ACE2 receptor and it is a significant step for SARS-CoV-2 to enter into target cells33,46. Computer modelling studies of the interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 RBD and ACE2 were able to identify the residues involved in this interaction and elucidate how the structural change benefits receptor recognition and virus entry into the host cell, that occurs by proteolytic processing of the Spike protein to promote cell-virus fusion47. Therefore, atomic details may clarify the importance and significance of investigating the changes in residues that facilitate efficient cross-species infection and human-to-human transmission34. Whereas the essential evolution and consequent mutation of SARS-CoV-2 takes place remotely from the RBD in the Spike protein, such evolution may facilitate the conformational change in specific residues, punctually interfering with the infection process that occurs after the virus binds to ACE248.

Recently, Warshel and co-workers studied the mechanism of the binding affinity changes for mutations at different Spike protein domains of SARS-CoV-2, Alpha, Beta and Delta variants using coarse-grained potential surface to calculate the binding free energy of SARS-CoV-2 to ACE249, concluding that the evolution of the virus takes place from the binding domain in the trimeric body of the Spike protein, which may facilitate the conformational change and the infection process. Chen and co-workers used machine learning model to analyze how the RBD mutations on the Omicron variant may affect the viral infectivity and efficacy of existing vaccines and antibody drugs50. They results indicated that the Omicron variant may be ten times more contagious than the Wild Type (WT) virus or about twice as infectious as the Delta variant, also based on the Spike protein binding domain50. More recently, Kumar and co-workers51 molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to investigate the interaction between the RBD of both the WT and Omicron variant with the ACE2 receptor and found that the Omicron Spike protein has an increased affinity for the ACE2 receptor, due to the presence of mutant residues51. Similarly, Socher and coworkers have used MD simulations of the RBD and ACE2 to analyze and compare the interaction pattern between the WT, Delta and Omicron variants, where they have identified residue 493 in Delta (glutamine) and Omicron (arginine) with altered binding properties towards ACE252. MD simulation have also been used to explore the effect of different possible mutations of the Spike key residues, which are the mutations found in the most relevant observed variants53. In this study, we have used all-atom accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) simulations54,55 to explore the impacts of the substitutions that occur in the Spike RBD of Alpha, Delta and Omicron variants in the binding with the human ACE2 receptor. In order to address the question whether variant infectivity and spreading is related to its binding to the receptor.

Methods

SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein is a class I fusion homotrimer glycoprotein that is composed a total length 1273 residues56 and the binding between the virus and the host cell is mediated by the interaction of the protein S receptor binding domain (RBD, located in the S1 domain) with the angiotensin converting enzyme receptor 2 (ACE2). Here, for the sake of simplicity, S protein RBD from SARS-CoV-2 was renamed as RBDx, where x represents the identification of each SARS-CoV-2 variant. The initial systems were built considering the coordinates of the RBD complex and the ACE2 (PDB code 6M0J)33. The protonation states of the protein residues were defined through the propKa program at pH 757. The amino acids were treated with the ff14SB force field58 using TLeap module included in AMBER 1659. Each system was solvated using TIP3P water60 model in a cubic box with 10.0 Å of the amino acid at the end for all Cartesian directions. Then, each system was neutralized using Na+ as contra-ions.

We used four minimization steps with 10,000 cycles for each step, applying minimization first to water, contra-ions and protein, in the last step the minimization was applied to all atoms in the system in order to decrease energy, adjust interactions and decrease contacts with conjugate gradient and steepest descent. The systems were heated linearly from 0 to 300 K (tempi = 0.0; temp0 = 300.0) to avoid excessive and sudden fluctuations of the solute in a time of 5 ns in NVT ensemble employing Langevin dynamics as thermostat (collision frequency of 2 ps) had been used to guarantee a system equilibrium. The SHAKE algorithm61 was employed to constraints all bonds involving hydrogen atoms.

First, we have performed 10 ns of Classical molecular dynamics (cMD) simulations to calculate the average dihedral and total potentials energies to be taken as reference for the accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) simulations. Then 200 ns of aMD simulations was carried out for each system: RBDWT–ACE2, RBDAlpha–ACE2, RBDOmicron–ACE2 and RBDDelta–ACE2 complex in NPT essemble.

In general, dynamic properties of proteins cannot be simulated directly using molecular dynamics because of nanosecond time scale limitations54, since the systems are trapped in potential energy minima with high free energy barriers for large numbers of computational steps54. The aMD is a useful technique for enhancing the sampling during MD simulation62,63. This technique is based on the reduction of energy barriers between the different states of a biological system54,64–66. The approach employ a modified potential transits from state to state at an accelerated rate, enabling the visit of more structures at energy minima54,64–66. In general, 500 ns of aMD simulation can be compared to values calculated from the 1 ms cMD simulation and the experimental values65,67–70. For this reason, we have used aMD technique in order to enhance sampling in the protein's conformational space, artificially reducing the energy barriers that separate different states of a given system54,55,71–74. Additionally, we used the Bio3D package75 to perform the principal component analysis (PCA). The PCs were obtained from the diagonalization of the covariance matrix obtained from the Cartesian coordinates of the superposed Cα atoms of complex structure. To avoid an underestimate of the atomic displacement, an iterated superposition procedure was applied before the PCA, where residues displaying the largest positional differences were excluded at each round until only the invariant ‘core’ residues remained76–79.

Protein–protein binding free energy

In this study, we also evaluated the binding energy differences between the complexes and then the decomposition energy was added to assess the energy contribution of each amino acid during the binding of RBD to ACE2. The binding free energy for the each RBD–ACE2 complex was obtained using:

| 1 |

Here, GRBD–ACE2 represent the average over the snapshots of a single trajectory of the MD RBD–ACE2complex, GRBD and GACE2 corresponds to the free energy of RBD and ACE2 protein, respectively. The binding free energy was obtained using MMGBSA method80,81 implemented in AMBER 1659.

In order to calculate free energy with MMGBSA (Eq. 2) 5000 frames were taken from the 10 ns of MD production using82–84:

| 2 |

where, is total gas phase energy (sum of , , and ); is sum of polar () and non-polar () contributions to solvation. It is important to note that the entropy contribution was not included in the calculations due to the difficulty of accurately calculating entropy for a large protein–protein complex85. It is also worth to note that the frames were taken from the most stable structure observed in PCA graphics.

Results and discussion

Analysis of molecular dynamics of RBD–ACE2 complex

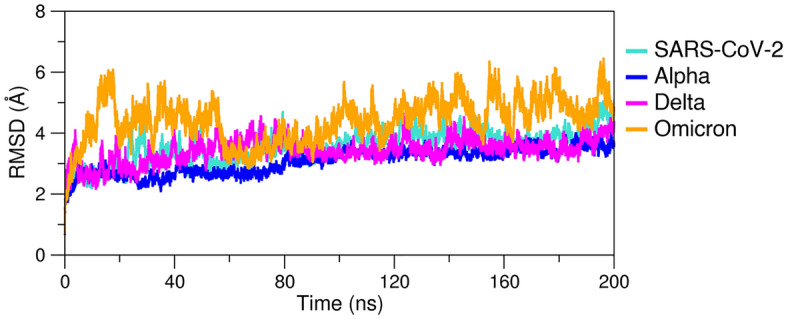

All-atom aMD simulations allowed to explore the conformations of protein–protein complex over time for each system: RBDWT–ACE2, RBDAlpha–ACE2, RBDOmicron–ACE2 and RBDDelta–ACE2 complex. Figure 1 shows the RMSD during 200 ns of aMD for each system with respect to the reference structure of the equilibrium step. RBDWT–ACE2, RBDAlpha–ACE2 and RBDDelta–ACE2 complexes were within fluctuation in a range of 1–3 Å (Fig. 1), while the RBDOmicron–ACE2 complex the present the different variation during simulation in a range of 1–4 Å (Fig. 1). Therefore, the structural equilibrium was reached for all system (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

RMSD for RBDWT–ACE2, RBDAlpha–ACE2, RBDOmicron–ACE2 and RBDDelta–ACE2 complexes.

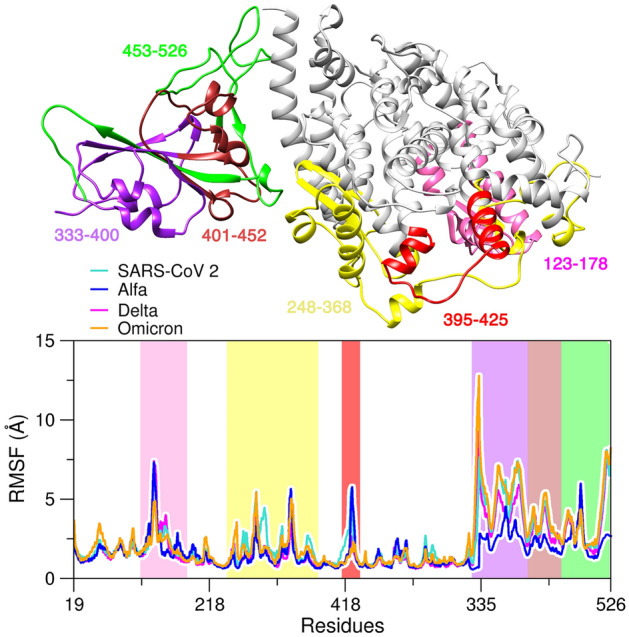

In order to obtain insight into flexibility of each residue in protein–protein complex, we have analyzed the Root-Mean-Square Fluctuations (RMSF) taken into consideration the fluctuations of the backbone atoms. In the RMSF analysis (Fig. 2) ACE2 shows the greatest fluctuation in regions 123 to 178 (in magenta), 395 to 425 (in red) and in the region of residues 248 to 368 (in yellow), that moves to interact with the viral RBD. the RBDAlpha residues show less fluctuation compared to the WT and its last variants (Delta and Omicron).

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional structure of ACE2 and RBD with RMSF regions for SARS-CoV-2, Alpha, Delta and Omicron systems.

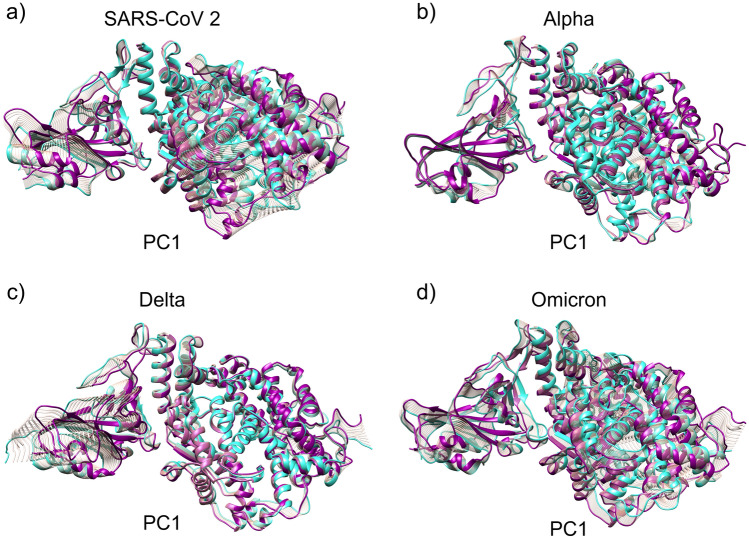

In this study, we also explore the flexible region in protein–protein complex, through essential dynamics analysis. The PCA graphs, were obtained using the combinations of PC1 vs PC2, PC2 vs PC3 and PC3 vs PC1 (Fig. S2), in which the clusters demonstrate two possible states for all systems in PC1 vs PC2. The color scales represent the trajectory time of the MD, separating the beginning of the structures in the initial time of the final structures of the MD, however, the Alpha variant already has a greater number of clusters, where each time interval is separated into small clusters.

For Omicron system the structures are visibly separated into blue structures and red structures (see SI, Fig. S2), indicating that the initial structures differ from the final ones, leading to variations in the aMD structures (Fig. 3). The PCA analysis showed that the RBDWT and the RBDmicron–RBDOmicron variant present greater conformational fluctuations, however, the RBDAlpha variant stands out for its greater stability. In PC1 there are not many movements in RBD and ACE2 (Fig. 3). The main movement of RBDWT and RBDmicron–RBDOmicron is similar because they have a greater number of movements. The Spike protein, via RBD, when it binds, causes changes in ACE2, as shown in Fig. 3. The other conformational changes are shown in PC2 and PC3 in Fig. S3 for all systems.

Figure 3.

Movements described for the first principal component (PC1) for each structure of ACE2 and RBD. (a) Moving in PC1 to the RBDWT complex (SARS-CoV-2) and ACE2 receptor. (b) changes in PC1 to RBDAlpha and ACE2. (c) Change moving of PC1 to RBDDelta and ACE2. (d) Moving from PC1 to the complex between RBDOmicron and ACE2. In turquoise, the initial structure of the movement, in dark magenta, the final structure and in gray, the intermediate structures of the movement. The conformational dynamics were obtained from 200 ns of aMD simulations.

Binding free energy MMGBSA and decomposition by residue

To assess the affinity of the virus for the human receptor and a possible potential risk of immune evasion by the variants, we calculated the free energy using MM/GBSA [∆Gbind (MMGBSA)] based on the points of greatest stability of the aMD trajectory (see Table 1). The RBDmicron–RBDOmicron shows the highest binding affinity to ACE2, reflecting the infectivity process, but its conformational fluctuations is similar to the other variants. RBDmicron–RBDOmicron present an adaptive and non-aggressive process when compared to the RBDAlpha (with free energy of binding equal to − 62.7836 kcal/mol), which demonstrated the lower free energy than RBDWT (− 59.7205 kcal/mol). Based on the higher conformational stability of the Alpha variant the high risk is evident and demonstrates a worrying risk of immune evasion due to its degrees of affinity with ACE2.

Table 1.

Binding free energy for WT systems (SARS-CoV-2) and variants (Alpha/Delta/Omicron).

| Energy (kcal/mol) | WT | Alpha | Delta | Omicron |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆Evdw | − 95.6 (0.18) | − 107.3 (0.21) | − 103.4 (0.16) | − 96.4 (0.16) |

| ∆Eele | − 625.8 (0.94) | − 608.5 (0.91) | − 955.1 (1.05) | − 1381.7 (1.24) |

| ∆EGB | 675.0 (0.87) | 667.5 (0.87) | 1006.3 (1.01) | 1416.2 (1.15) |

| ∆Esurf | − 13.4 (0.02) | − 14.5 (0.02) | − 13.9 (0.02) | − 13.5 (0.02) |

| ∆Ggas | − 721.3 (0.96) | − 715.8 (0.91) | − 1058.5 (1.09) | − 1478.1 (1.24) |

| ∆Gsol | 661.6 (0.86) | 653.0 (0.86) | 992.4 (0.99) | 1402.7 (1.15) |

| ∆Gbind (MMGBSA) | − 59.7 (0.28) | − 62.8 (0.23) | − 66.1 (0.21) | − 75.4 (0.23) |

The RBDDelta has a higher binding affinity with the human receptor compared to the RBDWT (− 66.1357 kcal/mol), which demonstrates the great concern of infections based on this variant. The high risk of infectivity is pointed out as greater among the variants because they have a more favorable ∆Gbind in comparison to RBDWT. Therefore, the risk of evolution and emergence of new variants may represent a major health concern due to the degree of affinity that evolves the greater affinity for the human receptor.

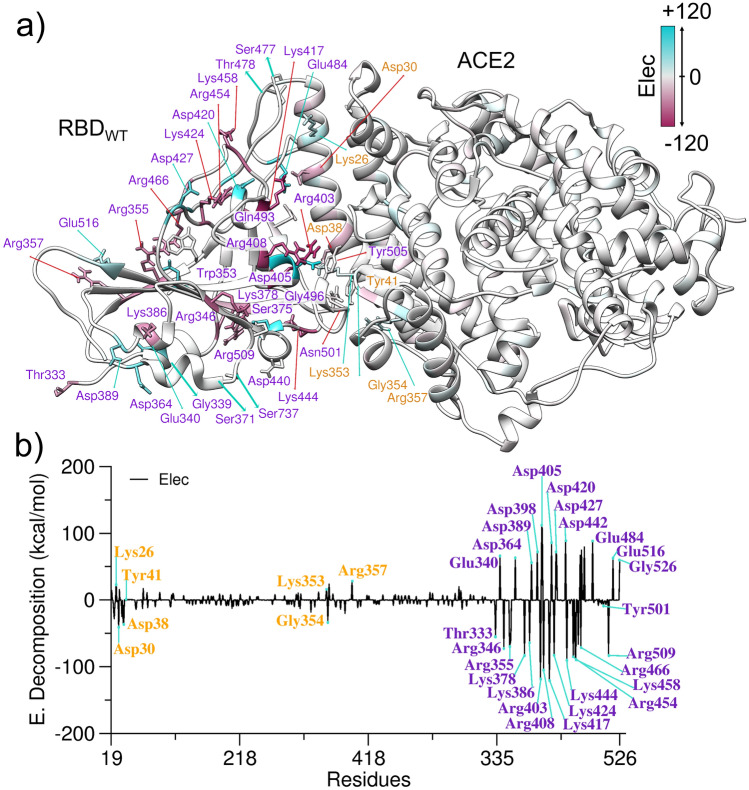

The effect of mutations can be investigated through the free energy calculations that track the influence of changes in certain positions49. The results of the energy of decomposition by residue for RBDWT–ACE2, RBDAlpha–ACE2, RBDOmicron–ACE2 and RBDDelta–ACE2 complex demonstrate that the RBD is the region that has more energy variations, attractive and repulsive, when evaluated the electrostatic contributions (see Fig. 4, Figs. S4, S5 and S6). The evaluation of the decomposition energy per residue shows the mutations N440K, T478K, Q493R and Q498R observed in RBDOmicron provide favorable interaction between RBDOmicron and ACE2. Curiously, all these mutations include positively charged residues Lys or Arg (see Table 2). For example, K478 in RBDOmicron present a stabilization effect (− 85.8 kcal/mol), while T478 in RBDWT has a destabilization effect (0.7 kcal/mol), see Table 2. Additionally, Table S2 shows the hydrogen bonds in the protein–protein interaction for the SARS-Cov-2, Alpha, Delta and Omicron system.

Figure 4.

(a) Three-dimensional structure of the RBDWT and ACE2 complex with the electrostatic energy regions. (b) Decomposition energy per residue for the RBDWT system connected to ACE2. The label in orange is from the ACE2 region and in purple is from RBD.

Table 2.

Decomposition energies per residue in kcal/mol for the main mutation positions of RBD WT, Alpha, Delta and Omicron.

| SARS-CoV-2 | Alpha | Delta | Omicron | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G339 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | G339D | 68.4 | ||

| S371 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.1 | S371L | 0.8 | ||

| S373 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | S373P | 0.6 | ||

| S375 | − 0.3 | − 0.3 | − 0.1 | S375F | − 0.4 | ||

| K417 | − 121.2 | − 131.5 | − 112.4 | K417N | − 2.3 | ||

| N440 | − 0.4 | − 0.3 | − 0.2 | N440K | − 98.6 | ||

| G446 | 0.3 | − 0.2 | − 0.2 | G446S | 1.2 | ||

| L452 | − 0.7 | − 0.6 | L452R | − 90.5 | L452 | − 1.4 | |

| S477 | − 1.1 | − 1.7 | − 1.4 | S477N | − 0.6 | ||

| T478 | 0.7 | − 2.4 | T478K | − 82.6 | T478K | − 85.8 | |

| E484 | 88.2 | 94.4 | 93.8 | E484A | 0.1 | ||

| Q493 | − 8.7 | − 11.6 | − 8.8 | Q493R | − 163.7 | ||

| G496 | − 3.6 | − 3.1 | − 4.9 | G496S | − 6.3 | ||

| Q498 | − 6.7 | − 2.1 | − 7.4 | Q498R | − 161.0 | ||

| N501 | − 8.6 | N501Y | − 8.1 | − 10.1 | N501Y | − 2.2 | |

| Y505 | − 7.4 | − 5.5 | − 8.0 | Y505H | − 1.4 | ||

The N501Y mutation in the RBDAlpha has a very similar contribution to the RBDWT system. This mutation does not cause such apparent changes in the energetic contributions. Therefore, its conformational stability is the main feature that contributes to the better binding of RBDAlpha to ACE2, compared to the RBDWT. The alterations in the Delta variant cause a highly attractive energy, in which the residue L352R had an energetic contribution of − 90,524 kcal/mol and T478K equal to − 82,654 kcal/mol (see Table 2), indicating that there is a great improvement in the binding with the receptor. The mutations present in RBDOmicron demonstrate that during the gain in the energetic contribution of the residues.

Some mutations present in RBDOmicron (N440K, T478K, Q493R, Q498R) demonstrate that substitutions for positively charged residues guide an improvement in the contribution to the interaction with ACE2 (Fig. S7). T478K is located in a more solvent-oriented region, allowing interaction with ACE2, due to the increase in the side chain Fig. S7a. As well, the Q493R substitution allows favorable interaction with negatively charged residues of ACE2 such as Asp38 and Glu35, improving the binding with the receptor and increasing the affinity of the Spike protein (Fig. S7b). The N440K in the micron Omicron is located in the region most focused on the solvent, increasing the contribution of this region with the medium (Fig. S7c), whereas the Q498R substitution improves the protein–protein interaction since this contribution is 24 times greater in relation to the WT, demonstrating that these substitutions are essential for improving interaction with ACE2 (Fig. S7d).

A recent study has suggested that RBDOmicron present a slightly reduced binding to ACE2 compared to RBDWT (RBD of the original Wuhan strain)86 and RBDDelta. The EC50 values were determined to be 120, 150 and 89 ng/mL for RBDWT, RBDOmicron and RBDDelta, respectively86. Other experimental study have proposed that RBDOmicron shows weaker binding affinity than RBDDelta to ACE287. Han and coworkers have measured the binding affinities of the RBDs to ACE2 with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) assay88. They found that RBDWT, RBDOmicron and RBDDelta binds to ACE2 with a dissociation constant (KD) of 24.63 nM, 31.40 and 25.07. Other experimental study shows that RBDOmicron and RBDDelta binds to ACE2 at a similar affinity to that of the RBDWT89.

On the other hand, Lin and coworkers have obtained kinetic-affinity values of 87.9 nM for RBDWT and 40.8 nM for RBDOmicron. These values highlight ~ 2.2-fold-enhanced receptor-binding with RBDOmicron90. A recent computational study have investigated the interaction between the RBD of both the WT and Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 with the ACE2 receptor using molecular dynamics and molecular mechanics-generalized Born surface area (MM-GBSA)-based binding free energy calculations51. Authors have carried out 100 ns of MD simulations for each complex and have suggested that the RBDOmicron has an increased affinity for the ACE2 receptor in comparison to RBDWT51. This last study has a closer relationship to our strategy used in here. The main difference is that we are describing computational result from 200 ns of aMD to explore molecular details interactions that occur in the Spike RBD of Alpha, Delta and Omicron variants in the binding with the ACE2 receptor. It is important to note that some bioinformatic models predicted an increase in the ACE2 binding affinity of RBDOmicron91. Here, our results are suggesting that complexes studied have similar fluctuations and that mutations present in RBDOmicron, RBDDelta and RBDAlpha increase the binding to ACE2 compared to RBDWT.

Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of residues mutation on structural and energetics of Spike protein RBD from SARS-CoV-2 variants in complex with the human ACE2 receptor. All-atoms accelerated Molecular Dynamics simulations and PCA analysis shows that that the RBDOmicron–ACE2 complex present similar fluctuation in comparison to S protein from WT, Delta and Alpha variants. The binding affinity of each RBDx to ACE2 was obtained using MM-GBSA methods. The results show that the trend in the calculated binding free energies correlates well with virus infectivity of each variant. The mutation in RBDOmicron increase the affinity of Spike protein for ACE2 and may explain Omicron's high transmissibility in comparison with other SARS-CoV-2 variants. The stabilization effect RBDOmicron–ACE2 complex is achieved manly due the substitution of uncharged residues by positively charged residues: Lys and Arg in key positions. Overall, our results may explain at molecular level the effect of key mutations in the Spike protein for virus infectivity.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for their financial support. We also thank to the support of the Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação (PROPESP/UFPA), likewise, the access of the computational resources of the Supercomputer Santos Dumont (SDumont) provided by the Laboratório de Computação Científica (LNCC), Apollo 2000 and Cluster CABANO provided by the Laboratório de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento de Fármacos — Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA).

Author contributions

C.H.S.C., C.A.B.F. equally contributed in the manuscript; J.L., C.H.S.C., C.A.B.F. contributed with the proposition and drafting of the work; C.H.S.C., C.A.B.F. performed research; J.L., C.H.S.C., C.A.B.F. wrote the manuscript; J.L., C.H.S.C., C.A.B.F. and C.N. analysis of results and the manuscript revision.

Data availability

All necessary files to conduct this work (.pdb and .parm7) can be found attached as the Supporting Information. The AMBER18 suite of programs and the Amber ff14SB force field were used to carry out the MD simulations and can found at https://ambermd.org/.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Clauber Henrique Souza da Costa and Camila Auad Beltrão de Freitas.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-12479-9.

References

- 1.Wang D, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Outbreak. World Health Organization; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu F, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu N, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osterrieder A, et al. Economic and social impacts of COVID-19 and public health measures: Results from an anonymous online survey in Thailand, Malaysia, the UK, Italy and Slovenia. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046863. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemente-Suárez VJ, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social, health, and economy. Sustainability. 2021;13:6314. doi: 10.3390/su13116314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update. World Health Organization; 2021. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald C-J, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: A narrative review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alencar CH, et al. High effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in reducing COVID-19-related deaths in over 75-year-olds, Ceará State, Brazil. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021;6:129. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6030129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta S, et al. Vaccinations against COVID-19 may have averted up to 140,000 deaths in the United States. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2021;40:1465–1472. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchan SA, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against Omicron or Delta infection. medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2021.12.30.21268565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eyre DW, et al. Effect of Covid-19 vaccination on transmission of alpha and delta variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez Bernal J, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawood AA. Mutated COVID-19 may foretell a great risk for mankind in the future. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35:100673. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korber B, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: Evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;182:812–827.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villoutreix BO, Calvez V, Marcelin A-G, Khatib A-M. In Silico Investigation of the New UK (B.1.1.7) and South African (501Y.V2) SARS-CoV-2 Variants with a Focus at the ACE2-Spike RBD Interface. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1695. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization . Classification of Omicron. World Health Organization; 2021. pp. 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodcroft, E. B. CoVariants: SARS-CoV-2 mutations and variants of interest (2021).

- 20.Hadfield J, et al. Nextstrain: Real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:4121–4123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Cheng G. Sequence analysis of the emerging SARS-CoV-2 variant Omicron in South Africa. J. Med. Virol. 2021;94:1728–1733. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization . Update on Omicron. World Health Organization; 2021. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulliam JRC, et al. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of the Omicron variant in South Africa. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.11.11.21266068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim H, et al. Hot spot profiles of SARS-CoV-2 and human ACE2 receptor protein protein interaction obtained by density functional tight binding fragment molecular orbital method. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16862. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73820-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H, et al. The digestive system is a potential route of 2019-nCov infection: A bioinformatics analysis based on single-cell transcriptomes. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.01.30.927806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang P, et al. Increased resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variant P.1 to antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:747–751. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei C, et al. Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J. Genet. Genomics. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berger I, Schaffitzel C. The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Balancing stability and infectivity. Cell Res. 2020;30:1059–1060. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Starr TN, et al. Deep mutational scanning of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain reveals constraints on folding and ACE2 binding. Cell. 2020;182:1295–1310.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian F, et al. N501Y mutation of spike protein in SARS-CoV-2 strengthens its binding to receptor ACE2. Elife. 2021;10:e69091. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luan B, Wang H, Huynh T. Molecular mechanism of the N501Y mutation for enhanced binding between SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein and human ACE2 receptor. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.04.425316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng B, et al. Recurrent emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike deletion H69/V70 and its role in the Alpha variant B.1.1.7. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109292. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lan J, et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang Y, Yang C, Xu X, Xu W, Liu S. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao X, Chakraborti S, Dimitrov AS, Gramatikoff K, Dimitrov DS. The SARS-CoV S glycoprotein: Expression and functional characterization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;312:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong SK, Li W, Moore MJ, Choe H, Farzan M. A 193-amino acid fragment of the SARS coronavirus S protein efficiently binds angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:3197–3201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Junxian O, et al. V367F mutation in SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD emerging during the early transmission phase enhances viral infectivity through increased human ACE2 receptor binding affinity. J. Virol. 2021;95:e00617-21. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00617-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Daniel W, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CAM, Rottier PJM. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: Structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 2003;77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harvey WT, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:409–424. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donoghue M, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme–related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ. Res. 2000;87:e1–e9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao Y, et al. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.01.26.919985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo J, Huang Z, Lin L, Lv J. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease: A viewpoint on the potential influence of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers on onset and severity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016219. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shang J, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581:221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yushun W, et al. Receptor recognition by the novel coronavirus from Wuhan: An analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J. Virol. 2021;94:e00127-20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bai C, Warshel A. Critical differences between the binding features of the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:5907–5912. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c04317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bai C, et al. Predicting mutational effects on receptor binding of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 variants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:17646–17654. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c07965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Wang R, Gilby NB, Wei G. Omicron variant (B.1.1.529): Infectivity, vaccine breakthrough, and antibody resistance. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021 doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar R, Murugan NA, Srivastava V. Improved binding affinity of omicron’s spike protein for the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor is the key behind its increased virulence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:3409. doi: 10.3390/ijms23063409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Socher E, Heger L, Paulsen F, Zunke F, Arnold P. Molecular dynamics simulations of the delta and omicron SARS-CoV-2 spike–ACE2 complexes reveal distinct changes between both variants. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022;20:1168–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miotto M, et al. Inferring the stabilization effects of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the binding with ACE2 receptor. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:20221. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02946-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hamelberg D, Mongan J, McCammon JA. Accelerated molecular dynamics: A promising and efficient simulation method for biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:11919–11929. doi: 10.1063/1.1755656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kukol, A. Molecular Modeling of Proteins, 2nd edn, 1215 (2014).

- 56.Watanabe Y, Allen JD, Wrapp D, McLellan JS, Crispin M. Site-specific glycan analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike. Science. 2020;369:330–333. doi: 10.1126/science.abb9983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Søndergaard CR, Olsson MHM, Rostkowski M, Jensen JH. Improved treatment of ligands and coupling effects in empirical calculation and rationalization of pKa values. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2284–2295. doi: 10.1021/ct200133y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maier JA, et al. ff14SB: Improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Case, D. A., Betz, R. M., Cerutti, D. S., Cheatham, T. E. III, Darden, T. A., Duke, R. E., Giese, T. J., Gohlke, H., Goetz, A. W., Homeyer, N., Izadi, S., Janowski, P., Kaus, J., Kovalenko, A., Lee, T. S., LeGrand, S., Li, P., Lin, C., Luchko, T., Luo, R., Madej, B. & Mermelstein, D. L. X. and P. A. K. AMBER 2016 (Univ. California, 2016).

- 60.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. doi: 10.1063/1.445869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kräutler V, van Gunsteren WF, Hünenberger PH. A fast SHAKE algorithm to solve distance constraint equations for small molecules in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2001;22:501–508. doi: 10.1002/1096-987X(20010415)22:5<501::AID-JCC1021>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voter AF. A method for accelerating the molecular dynamics simulation of infrequent events. J. Chem. Phys. 1997;106:4665–4677. doi: 10.1063/1.473503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Voter AF. Hyperdynamics: Accelerated molecular dynamics of infrequent events. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997;78:3908–3911. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.3908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hamelberg D, McCammon JA. Fast peptidyl cis–trans isomerization within the flexible Gly-rich flaps of HIV-1 protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13778–13779. doi: 10.1021/ja054338a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Markwick PRL, Bouvignies G, Blackledge M. Exploring multiple timescale motions in protein GB3 using accelerated molecular dynamics and NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4724–4730. doi: 10.1021/ja0687668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bucher D, Pierce LCT, McCammon JA, Markwick PRL. On the use of accelerated molecular dynamics to enhance configurational sampling in ab initio simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:890–897. doi: 10.1021/ct100605v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pierce LCT, Salomon-Ferrer R, de Augusto F, Oliveira C, McCammon JA, Walker RC. Routine access to millisecond time scale events with accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:2997–3002. doi: 10.1021/ct300284c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berndt KD, Beunink J, Schroeder W, Wuethrich K. Designed replacement of an internal hydration water molecule in BPTI: Structural and functional implications of a Gly-to-Ser mutation. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4564–4570. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng MH, Kaya C, Bahar I. Quantitative assessment of the energetics of dopamine translocation by human dopamine transporter. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:5336–5346. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b10340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang J, Alekseenko A, Kozakov D, Miao Y. Improved modeling of peptide–protein binding through global docking and accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019;6:112. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patrick R, et al. Using accelerated molecular dynamics simulation to elucidate the effects of the T198F mutation on the molecular flexibility of the West Nile virus envelope protein. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:9625. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Markwick PRL, McCammon JA. Studying functional dynamics in bio-molecules using accelerated molecular dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:20053–20065. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22100k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roe DR, Bergonzo C, Cheatham TE. Evaluation of enhanced sampling provided by accelerated molecular dynamics with Hamiltonian replica exchange methods. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:3543–3552. doi: 10.1021/jp4125099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li C, et al. Conformational changes of glutamine 5′-phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase for two substrates analogue binding: Insight from conventional molecular dynamics and accelerated molecular dynamics simulations. Front. Chem. 2021;9:51. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.640994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grant BJ, Rodrigues APCC, ElSawy KM, McCammon JA, Caves LSDD. Bio3d: An R package for the comparative analysis of protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2695–2696. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.da Costa, C. H. S. et al. Assessment of the PETase conformational changes induced by poly(ethylene terephthalate) binding. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Costa CHS, et al. Computational study of conformational changes in human 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme reductase induced by substrate binding. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019;37:4374–4383. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2018.1549508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.da Costa CHS, et al. Unraveling the conformational dynamics of glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent enzyme of Leishmania mexicana. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1742206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grosso M, Kalstein A, Parisi G, Roitberg AE, Fernandez-Alberti S. On the analysis and comparison of conformer-specific essential dynamics upon ligand binding to a protein. J. Chem. Phys. 2015;142:245101. doi: 10.1063/1.4922925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Srinivasan J, Cheatham TE, Cieplak P, Kollman PA, Case DA. Continuum solvent studies of the stability of DNA, RNA, and phosphoramidate–DNA helices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9401–9409. doi: 10.1021/ja981844+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kollman PA, et al. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: Combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lill MA, Thompson JJ. Solvent interaction energy calculations on molecular dynamics trajectories: Increasing the efficiency using systematic frame selection. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011;51:2680–2689. doi: 10.1021/ci200191m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Case DA, et al. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cui Q, et al. Molecular dynamics—solvated interaction energy studies of protein-protein interactions: The MP1–p14 scaffolding complex. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;379:787–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang Y, Liu H, Yao X. Understanding the molecular basis of MK2-p38α signaling complex assembly: Insights into protein-protein interaction by molecular dynamics and free energy studies. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:2106–2118. doi: 10.1039/c2mb25042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schubert M, et al. Human serum from SARS-CoV-2-vaccinated and COVID-19 patients shows reduced binding to the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. BMC Med. 2022;20:102. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02312-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron RBD shows weaker binding affinity than the currently dominant Delta variant to human ACE2. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:8. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00863-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Han P, et al. Receptor binding and complex structures of human ACE2 to spike RBD from omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2022;185:630–640.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dhiraj M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein–ACE2 complex. Science. 2022;375:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.abn7760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin S, et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron spike RBD reveals significantly decreased stability, severe evasion of neutralizing-antibody recognition but unaffected engagement by decoy ACE2 modified for enhanced RBD binding. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022;7:56. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00914-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Woo HG, Shah M. Omicron: A heavily mutated SARS-CoV-2 variant exhibits stronger binding to ACE2 and potently escape approved COVID-19 therapeutic antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:830527. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.830527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All necessary files to conduct this work (.pdb and .parm7) can be found attached as the Supporting Information. The AMBER18 suite of programs and the Amber ff14SB force field were used to carry out the MD simulations and can found at https://ambermd.org/.