Abstract

Background

Tolerance of low temperature has a significant impact on survival and expansion of invasive snail Pomacea canalicuata. Cold acclimation can enhance cold tolerance of Pomacea canalicuata. To elucidate the molecular mechanism of P. canaliculata’s responses to cold acclimation and cold stress, a high-throughput transcriptome analysis of P. canaliculata was performed, and gene expression following artificial cold acclimation and then cold stress at 0 °C for 24 h was compared using RNA sequencing.

Results

Using the Illumina platform, we obtained 151.59 G subreads. A total of 5,416 novel lncRNAs were identified, and 3166 differentially expressed mRNAs and 211 differentially expressed lncRNAs were screened with stringent thresholds. The potential antisense, cis and trans targets of lncRNAs were predicted. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes enrichment analysis showed that many target genes were involved in proteasome, linoleic acid metabolism and retinol metabolism under cold acclimation. The lncRNA of P. canaliculata could participate in cold acclimation by regulating the expression of E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, 26S proteasome non-ATPase dependent regulation subunit, glutathione S-transferase, sodium/glucose cotransporter and cytochrome P450.

Conclusions

These results broaden our understanding of cold acclimation and cold stress associated lncRNAs and mRNAs, and provide new insights into lncRNA mediated regulation of P. canaliculata cold acclimation and cold stress response.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-022-08622-5.

Keywords: Pomacea canaliculata, Cold acclimation, Cold stress, Transcriptome, lnc RNA

Background

Pomacea canaliculata is a pantropical species of invasive freshwater gastropods notorious for damaging wetlands and agriculture. Whether an introduced species becomes invasive is dependent on both the characteristics of the niche and the biological traits of the species [1, 2]. Niche-based characteristics include climate suitability [3], resource availability [4] and presence of potential competitors [5]. Trait-based characteristics of the species include life span, growth rate, fecundity, dispersal ability, dietary spectrum, genetic adaptation, and environmental tolerance [6–8]. For P. canaliculata, the strong abilities to feed [9], grow and reproduce [10] are known to be associated with their strong invasion. In addition to the characteristics described above, tolerance of low temperature is another key characteristic for P.canaliculata to expand in temperate East Asia and tropical Southeast Asia [11, 12].

For many invasive species, the climate of the new habitat is the major factor determining colonization success. Species that cannot tolerate or adapt to local climate will disappear shortly after initial invasion [13]. The natural range of P. canaliculata consists of the Lower Paraná, Uruguay, and La Plata basins [14]. For P. canaliculata, growth, feeding and crawling are completely suppressed at temperature below 10 °C [15]. In temperate Japan, P. canaliculata inhabiting paddy fields exhibit high mortality in winter, with levels ranging from 65 to 99.8%. The expansion range of P. canaliculata in East Asia has been restricted by cold winter weather [11, 16, 17].

There are two ways for P. canaliculata to resist cold climates. Behaviorally, snails can bury themselves into soil or under rice straw when the paddy fields are drained before harvest. The temperatures under the straw generally remain above 0 °C, even when the soil surface temperatures drop below -5 °C [18]. Another approach is the physiological enhancement of cold tolerance. P. canaliculata in paddy fields in temperate Japan increase their cold tolerance before the onset of winter [18]. Gradually decreasing temperatures (cold-acclimation) serve as the main environmental cue for P. canaliculata to enhance cold tolerance. After cold acclimation, P. canaliculata can enhance cold hardiness by accumulating low-molecular-weight compounds in their body, such as glucose, glycerol, glutamine and carnosine [13, 19]. In general, low-molecular-weight compounds can act as cryoprotectants, and their presence can decrease the supercooling points, prevent protein denaturation and reduce cuticular water loss by binding water [20]. Although previous studies showed that the expression of glycerol kinase (GK), heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), Na+/K+-ATPase (NKA), and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) genes is related to the cold hardiness of P. canaliculata [21], few studies focused on the molecular mechanism of increased cold hardiness.

With rapid development in high-throughput transcriptome sequencing technologies, the identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) triggered by cold response has been performed in a large number of species, helping to discover numerous non-coding RNA genes [22]. These efforts have led to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the adaptation of P. canaliculata to low temperatures. LncRNAs (Long non-coding RNAs) are over 200 nucleotides in length, have a low ability to code proteins, and account for the vast majority of ncRNAs [23]. LncRNAs have been identified to regulate gene expression in the close (cis-acting) or distant (trans-acting) regions of the genome through diverse mechanisms, such as promoter activity modification via nucleosome repositioning, DNA methylation, histone modification, accessory protein activation/gathering/transportation, repression, and epigenetic silencing [24, 25]. Numerous recent studies have indicated that lncRNAs can enhance the biological stress resistance by regulating expression of functional genes [26–28]. The lncRNA SVALKA was identified as a negative regulator of expression of C-repeat/dehydration-responsive element binding factors (CBFs) and plant freezing tolerance [29–31]. Over-expression of TUG1 lncRNA (TUG1, taurine up-regulated gene 1) protects against cold-induced liver injury in Mus musculus by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation [32]. It has also been reported that lncRNAs are involved in response to cold stress in Wistar rats, giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) sperm, grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), and pear (Pyrus pyrifolia 'Huanghua') [33–36].

The participation of lncRNAs in cold acclimation and under cold stress of P. canaliculata, however, remains unclear. In this study, we explored the response of lncRNAs and mRNAs to cold acclimation and cold stress in P. canaliculata using next-generation sequencing (NGS) by performing RNA-seq. This study provides insight in understanding the molecular mechanism underlying cold response of P. canaliculata, and shed light on the potential roles of lncRNAs in cold acclimation and cold stress-responsive P. canaliculata.

Results

Survival rate of P.canaliculata

When the experiment ended, we put the remaining individuals of the cold acclimation group and the control group into two boxes with water at room temperature respectively. We observed that all individuals were active within 30 min in the cold acclimation group, but there were three snails died in the control group. The survival rates of the cold acclimation group and the non-cold acclimation group were 100.00 and 96.67%, respectively in the present study. These results were similar to previous study on P. canaliculata. Almost all P. canaliculata survived at 0 °C for 2 or 5 days whether or not they had undergone cold acclimated, the survival rates of the cold acclimation group and the non-cold acclimation group were 98.3 (± 2.9) % and 96.7 (± 5.8) % respectively [13].

Sequencing and assembly

As the main immune organ of gastropod mollusks, the hepatopancreas plays an important role in the organism’s resistance to biotic and abiotic threats [37]. Hepatopancreas samples from 12 snails were subjected to transcriptome sequencing and data analysis. The sequencing data of raw reads ranged from 11.90 to 13.31 Gb. The average Phred score Q30 of clean reads varied from 91.09 to 93.93%. The filtered reads were subsequently compared with the P. canaliculata reference genome [38], and the mapped reads from the 12 libraries covered 81.33–87.00% of the P. canaliculata genome (Supplement Table S1). All the sequences have been uploaded to the NCBI SRA database under the BioProject identifier PRJNA788380.

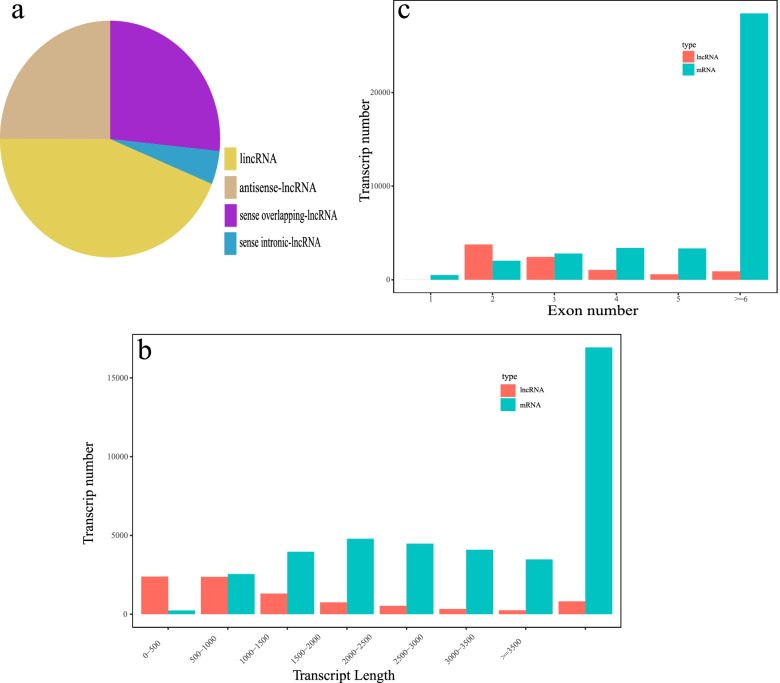

A total of 18,362 transcripts were assembled, and 5,416 novel lncRNAs were identified, 1,545 of which were classified as intergenic lncRNAs (also known as lincRNAs, 28.50%), 1,581 of which were classified as antisense lncRNAs (29.20%) and 2,289 of which were classified as sense overlapping lncRNAs (42.30%). The basic genomic features of these lncRNAs were characterized. Compared with protein coding genes, lncRNAs were typically 200–1500 bp in length and composed of fewer exons, with most containing two or three exons (Fig. 1). These results suggest that the majority of lncRNAs in P. canaliculata have shorter lengths and fewer exons compared to protein coding genes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of cold-responsive lncRNAs in P. canaliculata hepatopancreas. a four types of lncRNAs (lincRNA, antisense-lncRNA, sense overlapping-lncRNA and sense intronic-lncRNA) in hepatopancreas. b Numbers of mRNA and lncRNAs with different length. c Numbers of mRNA and lncRNAs containing different exon numbers

Differentially expressed genes and lncRNAs under cold stress

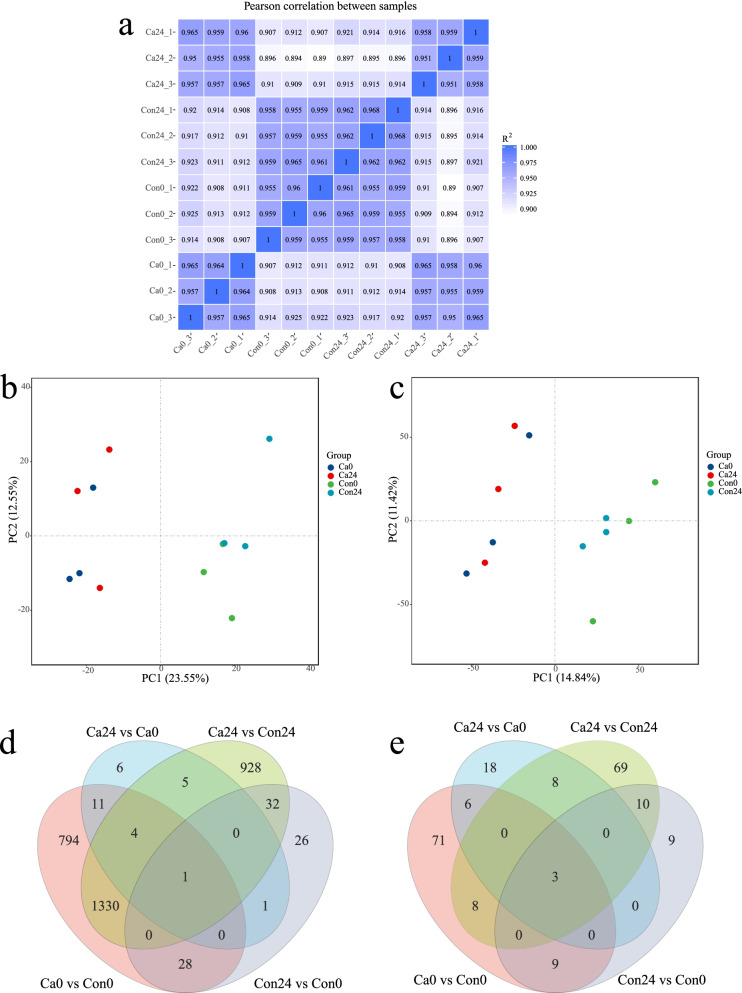

Expression levels were analyzed using the edgeR software to screen differentially expressed genes and lncRNAs (DELs) between the cold acclimation group and the control group. The three sample-replicates showed a high degree of concordance in gene expression (R2 correlation > 0.95, Fig. 2a). Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) on the transcriptomes revealed a clear discrimination between the cold acclimation group and the control group, indicating location-specific transcriptional identities (Fig. 2b, c). For Ca0 vs Con0, there were 2,168 DEGs identified, 1,129 were up-regulated and 1,039 were down-regulated. For Ca24 vs Con24, 2,300 DEGs were identified, 1,328 up-regulated and 972 down-regulated. Totally 28 (Ca24 vs Ca0) and 88 (Con24 vs Con0) significant DEGs were identified, including 18 up-regulated and 10 down-regulated genes altered between Ca24 and Ca0 and 33 up-regulated and 55 down-regulated genes altered between Con24 and Con0 (Table 1, Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Heat map of correlation coefficient 12 samples, principal component analysis (PCA) and venn plot for lncRNA and coding-gene expressions. a Heat map of correlation coefficient; b PCA for the coding-gene expressions for P. cancaliculata in two time points between the cold acclimation group and the control group; c PCA for the lncRNAs for P. cancaliculata in two time points between the cold acclimation group and the control group; d Venn plot for the protein coding genes of P. cancaliculata in two time points between the cold acclimation group and the control group; e Venn plot for lncRNAs for Pomacea cancaliculata in two time points between the cold acclimation group and the control group

Table 1.

Number of differential expression mRNA and lncRNA in experimental and control group of Pomacea canaliculata

| Comparison groups | Ca0 vs Con0 | Ca24 vs Con24 | Con24 vs Con0 | Ca24 vs Ca0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated mRNA | 1129 | 1328 | 33 | 18 |

| Down-regulated mRNAs | 1039 | 972 | 55 | 10 |

| Up-regulated lncRNAs | 57 | 60 | 14 | 18 |

| Down-regulated lncRNAs | 40 | 38 | 17 | 17 |

| Co-expression target genes | 637 | 875 | 169 | 135 |

| Co-location target genes | 1195 | 1085 | 455 | 439 |

Con0: 0 °C cold treatment of control group at 0 h; Con24: 0 °C cold treatment of control group at 24 h; Ca0: 0 °C cold treatment of experimental group at 0 h; Ca24: 0 °C cold treatment of control group at 24 h; Co-expression: the lncRNA function was predicted by mRNA genes associated with its expression; Co-location: the lncRNA function was predicted by mRNA genes associated with its location

We identified 195 DELs between the cold acclimation group and the control group, including 57 up-regulated and 40 down-regulated lncRNAs after cold acclimation (Ca0 vs Con0) and 60 up-regulated and 38 down-regulated lncRNAs after cold stress for 24 h (Ca24 vs Con24). A total of 35 DELs were identified after cold stress in cold acclimation group (Ca24 vs Ca0), including 18 up-regulated and 17 down-regulated lncRNAs. In control group (Con24 and Con0), 31 DELs were identified after cold stress (Table 1, Fig. 2e).

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of DEGs

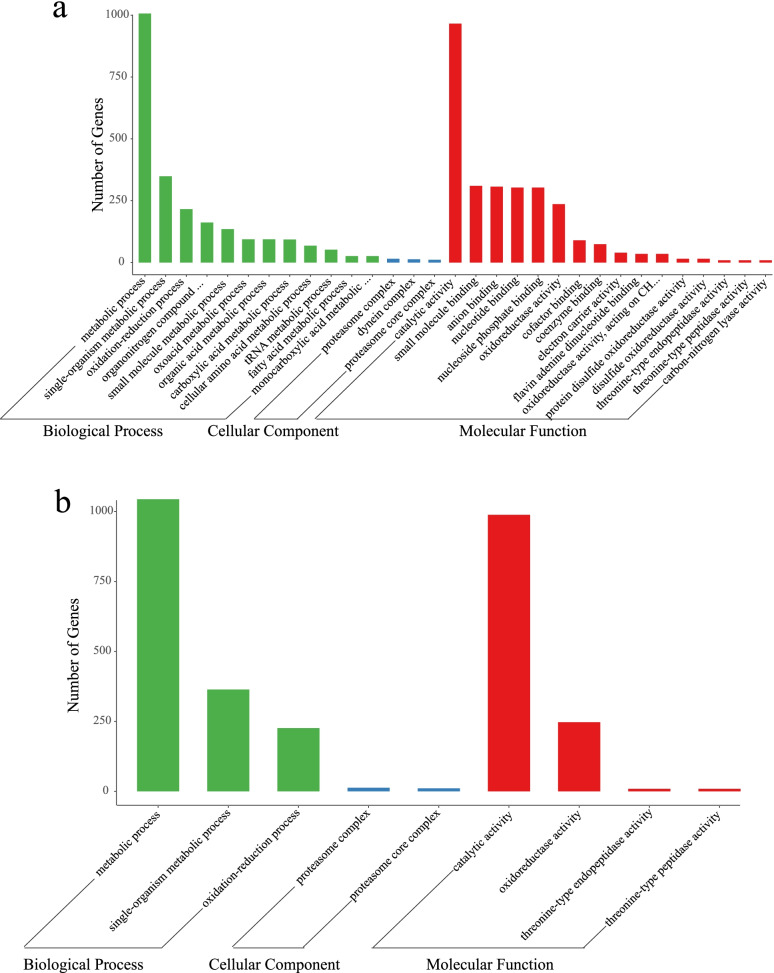

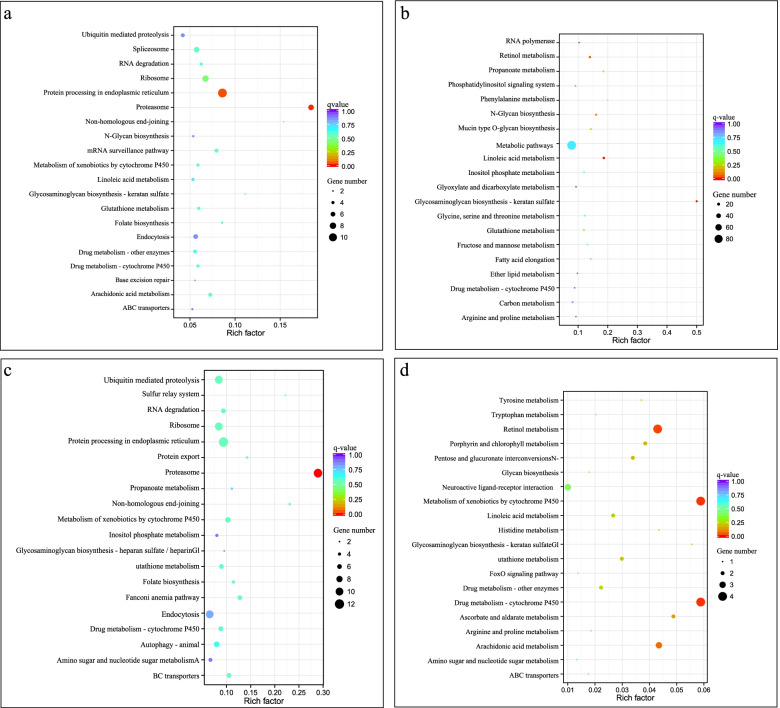

To identify the genes that exhibiting significant differences between the cold acclimation group and the control group, a pairwise comparison was conducted and significance was determined using edgeR software. The DEGs that are potentially associated with cold acclimation in P. canaliculata were analyzed based on GO enrichment, and the results are shown in Fig. 3. After cold acclimation (Ca0 vs Con0), the DEGs were significantly enriched in 31 GO terms, among which, 12 GO terms corresponded to biological processes, 3 to cellular components, and 16 to molecular functions (Fig. 3a). For the biological processes, “metabolic process” was the most strongly represented GO term, followed by “single-organism metabolic process”. A number of genes also belonged to interesting categories, such as “cellular amino acid metabolic process”, “fatty acid metabolic process” and “organonitrogen compound metabolic process”, which may participate in cold resistance and adaptation of P. canaliculata. The “catalytic activity” was highly represented among the molecular functions that the genes were involved in. A total of 2,168 genes were classified into 121 KEGG functional categories, which were significantly enriched in proteasome and glutathione metabolism KEGG pathways (Fig. 4a, Table S4).

Fig. 3.

The GO enrichment of DEGs which associated with cold acclimation in P. canaliculata. a cold acclimation group and control group after cold acclimation ended (Ca0 vs Con0). b cold acclimation group and control group after 24 h of cold stress at 0 °C (Ca24 vs Con24)

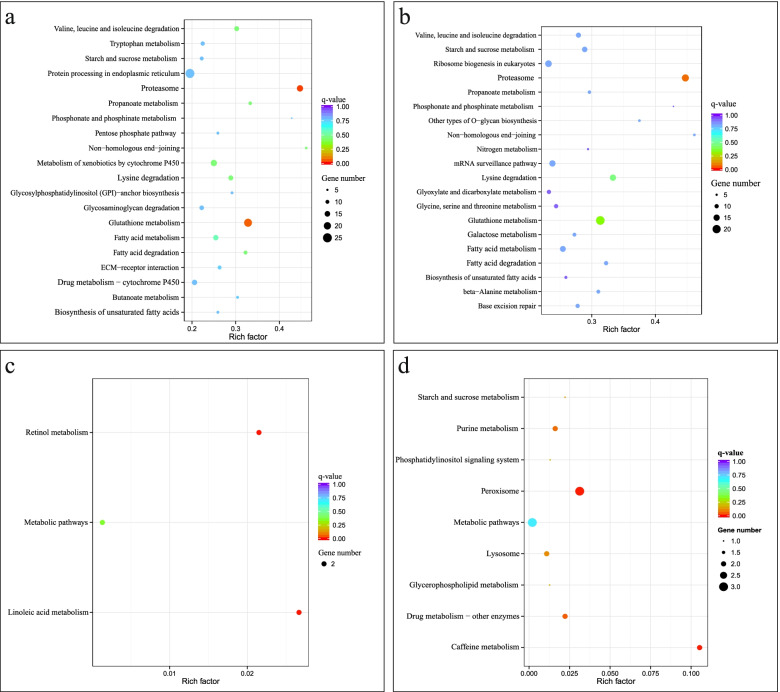

Fig. 4.

KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs between in P. canaliculata a Ca0 vs Con0. b Ca24 vs Con24. c Ca24 vs Ca0. d Con24 vs Con0

DEGs were associated with 9 GO terms under cold stress between cold acclimation group and control group (Ca24 vs Con24). The top two most significant annotated GO biological process pathways were “metabolic process” and “catalytic activity” (Fig. 3b). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that a total of 2300 DEGs were enriched in 118 KEGG pathways involved in the proteasome, glutathione metabolism, lysine degradation, and non-homologous end-joining. Starch and sucrose metabolism also contribute to the degradation of fatty acids. These DEGs were significantly enriched in proteasomal metabolic pathways (Fig. 4b). A large number of enriched terms were involved in metabolic process, catalytic activity and ion binding.

There was no significant GO term enrichment for DEGs in cold acclimation group (Ca24 vs Ca0). However, these DEGs were significantly enriched in linoleic acid metabolism and retinol metabolism pathways (Fig. 4c).

The DEGs identified in control group (Con24 vs Con0) exhibited no significant GO term enrichment. The 88 DEGs were involved in 9 KEGG pathways. They were significantly enriched in caffeine metabolism, peroxisome, drug metabolism and purine metabolism KEGG pathways (Fig. 4d).

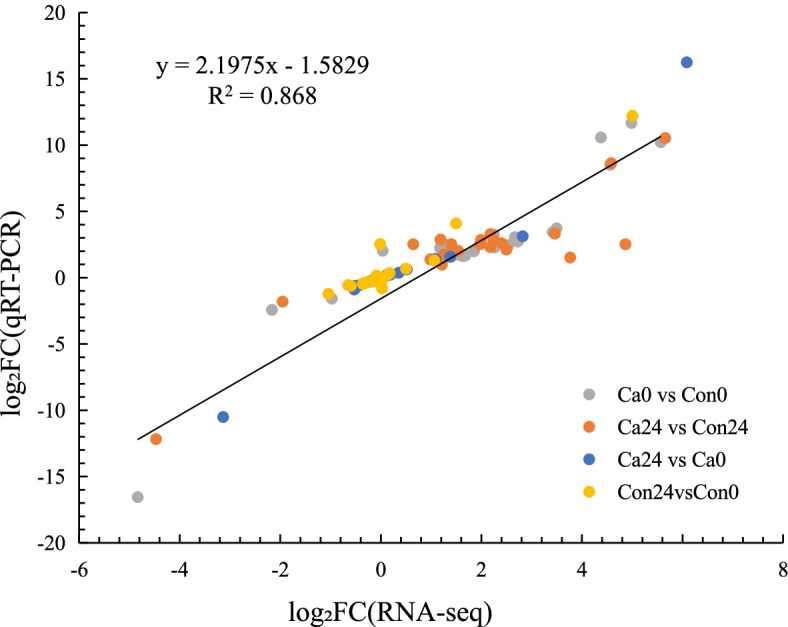

Validation of RNA-Seq results with qRT-PCR

A total of 13 DEGs related to cold adaptation in different signaling pathways and 9 DELs were selected to validate the gene expression using qRT-PCR. The mRNA/lncRNA expression changes were similar to those identified using RNA-seq. These findings indicate that the RNA-seq results are reliable and could be used for bioinformatic analysis (Fig. 5 and Fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

Correlation analysis of RNA-Seq and RT-qPCR in P. canaliculata. 22 candidate DEGs and DELs were measured by qPCR. The regression indicated a close correlation between methods (r2 = 0.868)

Functional prediction of long non-coding RNAs

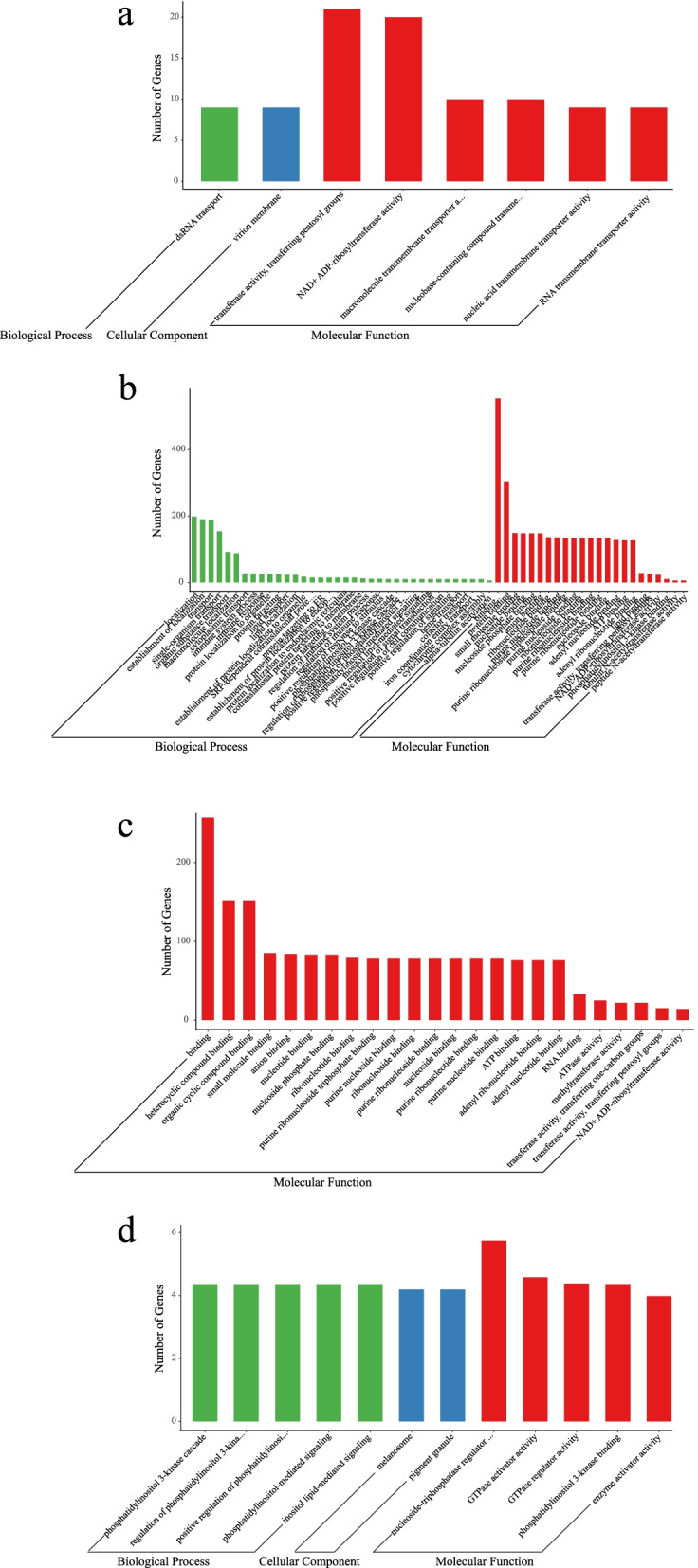

To understand the functional roles of the identified lncRNAs, we next explore the targets of lncRNAs. The co-expressed target genes of DELs after cold acclimation (Ca0 vs Con0) were not significantly enriched in any specific GO entries, however, they were significantly enriched in KEGG pathways associated with the proteasome and protein processing in the endoplasmic reticulum KEGG pathways (Fig. 6a). In control group (Con24 vs Con0), the co-expressed target genes of DELs were not significantly enriched in any GO entries or KEGG pathways (Fig. 6b). Co-expressed target genes of DELs exhibited no significant enrichment for any specific GO entries after cold stress (Ca24 vs Con24). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that the co-expressed target genes were enriched for the proteasome pathway (Fig. 6c). The co-expressed target genes of DELs in cold acclimation group (Ca24 vs Ca0) were significantly enriched in serine-type endopeptidase activity, serine-type peptidase activity and serine hydrolase activity and peptidase activity, acting on L-amino acid peptides under GO entries of molecular function (Table S5). They were also significantly enriched in drug metabolism-cytochrome P450, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 and retinol metabolism KEGG pathways (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

KEGG enrichment analysis of co-expressed target genes of DELs in P. canaliculata. “Rich factor” means that the ratio of the number of the genes in the specific subcluster and the number of genes annotated in this pathway. The greater the rich factor, thegreater the degree of enrichment. a Ca0 vs Con0; b Con24 vs Con0; c Ca24 vs Con24; d Ca24 vs Ca0

After cold acclimation (Ca0 vs Con0), co-localized target genes of DELs were significantly enriched in 8 GO terms (Fig. 7a), with no significant enrichment found for any specific KEGG pathways. GO enrichment analysis of co-localized target genes of DELs from Ca24 vs Con24 was similar to that of Ca0 vs Con0, but more DEL-associated genes were significantly enriched in binding, protein binding as well as other binding under the molecular function category (Fig. 7b). Co-localized target genes of DELs in Ca24 vs Ca0 were significantly enriched in the 24 molecular function GO terms (Fig. 7c). Most DEL-associated genes of Ca24 vs Ca0 were significantly enriched in ATPase activity, methyltransferase activity, transferase activity, transferring one-carbon groups, binding, heterocyclic compound binding, organic cyclic compound binding, small molecule binding as well as other binding under the molecular function category (Fig. 7c). KEGG enrichment analysis showed that these genes were significantly enriched in linoleic acid metabolism and retinol metabolism pathways (Fig. S2). In control group (Con24 vs Con0), co-localized target genes of DELs were significantly enriched in 12 GO terms, such as nucleoside-triphosphatase regulator activity, GTPase activator activity and GTPase regulator activity (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 7.

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of co-location target genes of DELs of P. canaliculata. a: Ca0 vs Con0. b Ca24 vs Con24. c Ca24 vs Ca0. d Con24 vs Con0

Discussion

Extreme temperatures often negatively affect both the survival of ectothermic animals and their biological functions, including reproduction, respiration, digestion, and excretion [39]. In order to reduce the negative effects of temperature on their performances, ectotherms are capable of modulating thermal tolerance over their lifetimes through a range of physiological adjustments triggered by pre-exposure to sub-lethal temperatures [40]. Low temperature acclimation involves a large suite of molecular and physiological variations [41]. In this study, we identified candidate mRNAs and lncRNAs in the P. canaliculata by simultaneously evaluating their differential expression patterns and correlations between the expression levels of coding and noncoding genes in response to cold stress. These lncRNAs share many characteristics of their eukaryotic counterparts: such as shorter length, fewer exons, and lower expression compared with mRNAs [42]. In our study, the lncRNA transcripts were relatively short with few exons and low levels of expression in comparison to protein coding mRNA transcripts (Fig. 1). These characteristics were also observed in Crassostrea gigas [43], Haliotis discus hannai [44] and other molluscs. We identified four aspects of P. canaliculata altered by cold acclimation and low temperature, which will be our focus of future work. According to the RNA-seq results, the DEGs and DELs in response to cold acclimation and cold stress related to glucose metabolism, ubiquitin–proteasome system, antioxidant system, and lipid metabolism were selected and the most important parts of them were discussed.

Candidate cold-resistance genes related to glucose metabolism

P. canaliculata enhances cold hardiness by increasing glycerol and glucose content in the body [19]. In the present study, expression of endoglucanase A, endoglucanase E-4 and maltase-glucoamylase genes increased in the cold acclimation group. Expression of these genes may provide additional glucose molecules for use as raw materials or increase energy of other metabolites by facilitating polysaccharide breakdown in the digestive tract. Expression of the phosphorylase B kinase gamma-catalytic chain gene may promote glycogen breakdown and accumulation of glucose and glycerol in P. canaliculata. Glycogen breakdown in Dryophytes chrysoscelis is transcriptionally promoted by increased expression of phosphorylase B kinase gamma-catalytic chain under freezing conditions [45]. The hexokinase type 2 gene is involved in the glycolytic pathway and may play an important role in increasing glucose content [46]. Its expression was up-regulated in the cold acclimation group after 24 h at 0 °C, consistent with previous studies in goldfish (Carassius auratus L) [47]. Additionally, the decreased expression of UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase and glycogenin-1 involved in glycogen synthesis may inhibit metabolic pathways related to synthesis of glucose and glycogen. The glucose transport in purified brush boarder membrane vesicles from hepatopancreatic epithelial cells of Panaeus japonicas and Homarus americanus is carrier-mediated via a sodium/glucose cotransporter transport protein [48]. The increased expression of sodium/glucose cotransporter may play an important role in glucose transport in P. canaliculata during cold acclimation. LncR112554377 can regulate the expression of sodium/glucose cotransporter through cis action, and this lncRNA may be involved in glucose transport.

Ubiquitin–proteasome system

Ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is the main protein degradation pathway, responsible for 80–90% of protein degradation in cells [49]. The UPS pathway involves two steps: first, misfolded or damaged proteins are labeled with multiple ubiquitin molecules, and then the labeled proteins are degraded by the 26S proteasome complex [50]. Compared to the control group, the E3 ubiquitin protein ligase HECTD1, RNF19B and RNF34 were up-regulated in the cold acclimation group. The DEGs were also found to be significantly enriched in the proteasome pathway, and the expression of several genes involved as structural components of the 26S proteasome, including 26S proteasome non-ATP-dependent regulatory subunits 3, 7, 12 and 13, significantly increased. The expression of lncRNNA112553564 was significantly up-regulated in Ca0 and Ca24 conditions, with log2 fold changes of 7.12 and 5.48, respectively. This lncRNA can regulate the expression of 26S proteasome non-ATPase dependent regulation subunit 3, 12 and 14 genes through trans-action. These results suggest that some lncRNAs regulate 26S proteasome genes to reduce the damage caused by cold stress.

Antioxidant system-related genes

A substantial amount of reactive oxygen free radicals are produced during temperature stress [51]. In order to alleviate the pressure caused by temperature stress, factors associated with antioxidant activity, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), increased [52]. Many aquatic animals enhance their antioxidant enzyme capacity by increasing their glutathione content [53]. We found that, after cold acclimation, DEGs were enriched in glutathione metabolism pathway, and the reduced form of glutathione could maintain the reductive state of the intracellular chambers and provide electrons for glutathione S-transferase (GST) and other enzymes. GST plays an important role in biological and abiotic stress responses by reducing oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species [54]. After cold acclimation, glutathione synthetase, the glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit involved in the first step of glutathione synthesis, GST subfamily omega and mu genes were up-regulated. Cytosol-aminopeptidase, which is involved in glutathione degradation, glutathione hydrolase 1 proenzyme and glutathione hydrolase-like Ywrd proenzyme were down-regulated. At the same time, when compared with Con0, the expression patterns of these genes were almost unchanged in Con24. These results suggest that cold acclimation induces synthesis of glutathione and GST, which can reduce the oxidative damage caused by cold stress. Meanwhile, cold-acclimation-induced lncRNA up-regulation is involved in GST synthesis. Prediction of lncRNA target genes indicated that lncRNA112567329 could regulate three GST omega subfamily members through cis action. LncRNA112568988, lncRNA112559114 and lncRNA112570305 could regulate the expression of two GST genes through trans action.

Lipid metabolism

Low temperatures alter the permeability of biofilms and stabilize weak chemical bonds, forcing the cell membrane to convert from a liquid phase to a thin-gel phase and thereby reducing membrane fluidity and affecting the functional properties of membrane proteins and membrane binding proteins [55, 56]. In insects, changes in membrane fluidity caused by cold temperatures can disrupt ion-water balance, causing muscle dysfunction, cold coma and death [57]. At low temperatures, plants, microorganisms and animals all increase the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in the phospholipids that constitute cell membranes, because the changes in physical membrane properties caused by the increased unsaturation compensate for the order of hydrocarbons present inside cell membranes at low temperatures [58]. After cold acclimation, the expression levels of genes related to synthesis of cholesterol, fatty acid, and unsaturated fatty acid were significantly increased. Ultra-long chain fatty acids and long-chain fatty acids are essential components of cell membranes. Elongation protein of very long chain fatty acids and fatty acid desaturase are key rate-limiting enzymes for fatty acid chain desaturation and elongation [59]. Cold acclimation can significantly increase the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes of Drosophila suzukii [60] and fatty acid desaturase can improve the low temperature tolerance and low temperature germination rate of rice [33]. Therefore, the adverse effects of low temperature on membrane fluidity were alleviated by increasing the genes of unsaturated fatty acid synthesis in P. canaliculata. Compared with Ca0, DEGs in Ca24 were significantly enriched in linoleic acid metabolism and retinol metabolism pathways. These pathways contain cytochrome P450 3A24 and cytochrome P450 3A5, which were down-regulated by 8.11 and 12.07 times respectively in Ca24. This reduced expression of cytochrome P450 3A24 and cytochrome P450 3A5 genes may minimize linoleic acid decomposition. It has been shown that the linoleic acid content of Drosophila larvae increases after cold acclimation [61], leading to a proposal that certain proportions of linoleic acid can maintain the fluidity at different temperatures [62]. The two members of cytochrome P450 gene family mentioned above were regulated in cis by lncRNA 112,557,458 and lncRNA112569753, respectively. We speculated that the decreased expression of cytochrome P450, may be a strategy to reduce the degradation rate of unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid, which can maintain the balance of cell membrane fluidity at lower temperatures.

Conclusion

In this study, transcriptome sequencing technology was used to investigate changes in protein coding genes and lncRNA expression in P. canaliculata after cold acclimation and cold stress. Genes related to cold tolerance and regulation of gene expression in P. canaliculata were identified. GO enrichment analysis showed that many DEGs were enriched in various metabolic processes. KEGG enrichment analysis showed that DEGs and many target genes of DELs were significantly enriched in proteasome, linoleic acid metabolism and retinol metabolism KEGG metabolic pathway. Furthermore, the lncRNA of P. canaliculata could participate in cold acclimation by regulating the expression of E3 ubiquitin protein ligase, 26S proteasome non-ATPase dependent regulation subunit, glutathione S-transferase, sodium/glucose cotransporter and cytochrome P450.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University. All the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University.

Sampling and treatment conditions

P. canaliculata were collected in June, 2020 from Lishui City, Zhejiang province, China. To eliminate confounding effects due to previous environmental differences, snails were reared in an artificial climate box for two weeks in the controlled climate chamber (photoperiod:16 L:8 D, illumination intensity: 2000 lx, relative humidity: 80%, temperature 25 °C). Lettuce and a few grains of carp food were provided daily as basic food. Aerated water was changed daily to remove the excrement and uneaten food debris.

Snails used in this study were then divided into two groups: the cold acclimation group and the control group (25 °C). There were three replicates with sample size of 30 snails with shell height of 28.84 ± 3.33 mm for each group, wrapped in a moist towel and confined in plastic containers (18 × 12 × 6 cm). Snails in the cold acclimation group were acclimated to cold starting at 25 °C, decreased by 5 °C every 5 d (at a rate of 1 °C a day) from 25 °C to 10 °C and continuously kept at 10 °C for four weeks [13]. Snails in the control group were not cold acclimated and treated at 25 °C during this period. After the cold acclimation, the cold acclimation group and the control group were exposed to cold treatment at 0 °C for 24 h in the same artificial climate box. No feeding was performed during the experiment. Hepatopancreas samples of three individuals were collected from the cold acclimation group and the control group after the cold acclimation ended and after 24 h cold stress at 0 °C, respectively. A total of 12 snails were sampled at two time points from the cold acclimation group (Ca0, Ca24) and the control group (Con0, Con24). Tissues were frozen immediately with liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C for RNA extraction.

RNA extraction, library construction, and RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using an RNA kit (Novogene, Beijing, China) and qualified using a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to assess possible contamination and degradation. RNA purity and concentration were examined using a NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer. RNA integrity and quantity were measured using an RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit with the Bioanalyzer 2100 system. RNA libraries for lncRNA-seq were prepared in a stranded manner with rRNA depletion. Briefly, the rRNA Removal Kit (RS-122–2402, Illumina, USA) was used to deplete the ribosomal RNA from total RNA following manufacturer’s instruction. Subsequently, the libraries were sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq 4000 by Novogene Co. Ltd (Beijing, China) and required reads (150 bp paired-end) were generated.

Transcript assembly and identification of lncRNAs

All raw data were first filtered by Fastp [63] to eliminate the low-quality data reads and adaptor sequences. Q30 and GC content of clean data were calculated at this stem. All downstream analyses were based on clean data of high quality. Clean reads for each sample were mapped to the reference genome [38] using the software HISAT2 [64]. Reads alignment results were transferred to the program StringTie [65] for transcript assembly. All transcripts were merged using Cuffmerge software [66]. LncRNAs were then identified from the assembled transcripts according to the following four steps [67, 68]: (1) removal of low expression transcripts with fragments per kilobase per million fragments mapped (FPKM) < 0.5 [69]; (2) removal of short transcripts less than 200 bp and 2 exons; (3) removal of transcripts with protein-coding capability according to Coding Potential Calculator 2 (CPC2), Pfam and Coding Non-Coding Index (CNCI) databases [70–72]; (4) removal of transcripts mapped within 1 kb of an annotated gene as determined by Cuffcompare.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes and lncRNAs

Quantifications of transcripts and genes were performed using StringTie software to obtain transcripts per million reads (TPM) values. EdgeR was used for differential expression analysis, and the resulting P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach [73] for controlling the false discovery rate. Genes with |log2 (fold change) |> 1 and padj < 0.05 were classified as differentially expressed.

qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression

The qRT-PCR assays were performed to validate the consistency of RNA-Seq analysis. qRT-PCR was performed on 13 DEGs selected from the RNA sequencing data according to their potential functional importance, and DELs from Primer-BLAST (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/) was utilized in primer design, and primer pair specificity was determined through PCR product sequencing (Table S2). Total RNA was extracted from hepatopancreas of 12 snails (the same individuals used for transcriptome sequencing, three biological replicates were set for each treatment at 0 h and 24 h, respectively) according to the instructions of the RNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). First strand cDNA was synthesized using a HiScript III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). RT-qPCR was then performed on each sample in triplicate with SYBR qPCR Master Mix (High ROX Premixed, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) using the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems™, Foster City, CA, USA) in a 20 μL reaction volume. The β-actin gene was used as an internal reference gene to normalize the gene expression levels [74]. The cycling parameters for the PCR amplification were as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, followed by 1 cycle of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 60 s. Amplification specificity was validated by melting curve analysis. The relative expression levels of target genes were calculated by the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (2 −ΔΔCt) and subjected to statistical analysis with SPSS (versions 22.0).

LncRNA target gene prediction

Target gene prediction for lncRNAs was carried out in two ways: the cis-acting target gene prediction (co-location analysis), and trans-acting target gene prediction (co-expression analysis). Based on the working model of cis-acting regulatory element activity, the protein coding genes located within 100 kb from the lncRNA of interest were selected as potential cis-acting targets. For trans-acting target prediction, the Pearson’ correlation coefficients (|r|> 0.95 and p-value < 0.05) between coding genes and lncRNAs were calculated and analyzed to identify trans-acting regulatory elements.

GO and KEGG enrichment analyses

Analyses of GO and KEGG [75–77] enrichment for DEGs or DELs target genes were performed using the clusterProfiler [78] in R package, with corrections made for gene length bias. Enrichment was considered to be significant when the corrected q-values was less than 0.05.

Availability of supporting data

Supplementary files Table S1 to S5 and Fig. S1 to S2 are available in the additional files.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. S1. Verification of the selected DEGs and DELs by qRT-PCR as compared with RNA-seq data. a: Ca0 vs Con0; b: Con24 vs Con0; c: Ca24 vs Ca0; d: Ca24 vs Con24. The gene marked red represents differentially expressed gene.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. S2. KEGG enrichment analysis of co-location target genes of DELs in cold acclimation group after cold stress (Ca24 vs Ca0). “Rich factor” means that the ratio of the number of the genes in the specific subcluster and the number of genes annotated in this pathway.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S1. Quality control (QC) information for mRNA sequences in Pomacea canaliculata. Table S2. The list of candidate genes forqRT-PCR validation in Pomacea canaliculata. Table S3. The 2-△△Ct values of candidategenes for qRT-PCR validation in Pomacea canaliculata.

Additional file 4: Table S4. KEGG pathways with differentially expressed genes and target genes from differentially expressed lncRNAs in different groups

Additional file 5: Table S5. Significant GO classifications associated with target genes from differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in different groups

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

L.C. designed the study, Q.X. and Y.F.L performed the experiments and data analysis, Q.X. and Y.F.L, P.L. and L.C. discussed the study design and data analysis. Q.X. drafted the manuscript. Y.F.L, H.L., Y.C., W.W., P. L., and L.C. revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31770402 and No.32170434), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20171407), the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (No. KYCX21_0917).

Availability of data and materials

Raw reads for the transcriptomic analysis have been uploaded on the SRA database from NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA788380 and will be available after publication.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from The Animal Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University. All the experimental procedures were approved by The Animal Research Ethics Committee of Nanjing Normal University. The manuscript adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines for the reporting of animal experiments, and the study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qi Xiao and Youfu Lin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Peng Li, Email: lipeng@njnu.edu.cn.

Lian Chen, Email: chenlian_2004@163.com.

References

- 1.Hayes KR, Barry SC. Are there any consistent predictors of invasion success? Biol Invasions. 2008;10(4):483–506. doi: 10.1007/s10530-007-9146-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mu HW, Sun J, Fang L, Luan TG, Williams GA, Cheung SG, Wong CKC, Qiu JW. Genetic basis of differential heat resistance between two species of congeneric freshwater snails: insights from quantitative proteomics and base substitution rate analysis. J Proteome Res. 2015;14(10):4296–4308. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellard C, Thuiller W, Leroy B, Genovesi P, Bakkenes M, Courchamp F. Will climate change promote future invasions? Global Change Biol. 2013;19(12):3740–3748. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenthal DM. Interactions between resource availability and enemy release in plant invasion. Ecol Lett. 2006;9(7):887–895. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thiebaut G. Does competition for phosphate supply explain the invasion pattern of Elodea species? Water Res. 2005;39(14):3385–3393. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2005.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson MH, Fitter A. The characters of successful invaders. Biol Conserv. 1996;78(1–2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/0006-3207(96)00025-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolar CS, Lodge DM. Progress in invasion biology: predicting invaders. Trends Ecol Evol. 2001;16(4):199–204. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franks SJ, Munshi-South J. Go forth, evolve and prosper: the genetic basis of adaptive evolution in an invasive species. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(9):2137–2140. doi: 10.1111/mec.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estebenet AL, Martin PR. Pomacea canaliculata (Gastropoda: ampullariidae): life-history traits and their plasticity. Biocell. 2002;26(1):83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lach L, Britton DK, Rundell RJ, Cowie RH. Food preference and reproductive plasticity in an invasive freshwater snail. Biol Invasions. 2000;2(4):279–288. doi: 10.1023/A:1011461029986. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito K. Environmental factors influencing overwintering success of the golden apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae), in the northernmost population of Japan. Appl Entomol Zool. 2002;37(4):655–661. doi: 10.1303/aez.2002.655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida K, Matsukura K, Cazzaniga NJ, Wada T. Tolerance to low temperature and desiccation in two invasive apple snails, Pomacea canaliculata and P. maculata (Caenogastropoda: Ampullariidae), collected in their original distribution area (Northern and Central Argentina) J Mollus Stud. 2014;80:62. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyt042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsukura K, Izumi Y, Yoshida K, Wada T. Cold tolerance of invasive freshwater snails, Pomacea canaliculata, P. maculata, and their hybrids helps explain their different distributions. Freshwater Biol. 2016;61(1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes KA, Cowie RH, Thiengo SC, Strong EE. Comparing apples with apples: clarifying the identities of two highly invasive Neotropical Ampullariidae (Caenogastropoda) Zool J Linn Soc-Lond. 2012;166(4):723–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00867.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seuffert ME, Burela S, Martin PR. Influence of water temperature on the activity of the freshwater snail Pomacea canaliculata (Caenogastropoda: Ampullariidae) at its southernmost limit (Southern Pampas, Argentina) J Therm Biol. 2010;35(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida K, Hoshikawa K, Wada T, Yusa Y. Life cycle of the apple snail Pomacea canaliculata (Caenogastropoda: Ampullariidae) inhabiting Japanese paddy fields. Appl Entomol Zool. 2009;44(3):465–474. doi: 10.1303/aez.2009.465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida K, Hoshikawa K, Wada T, Yusa Y. Patterns of density dependence in growth, reproduction and survival in the invasive freshwater snail Pomacea canaliculata in Japanese rice fields. Freshwater Biol. 2013;58(10):2065–2073. doi: 10.1111/fwb.12191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada T, Matsukura K. Seasonal changes in cold hardiness of the invasive freshwater apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Lamarck) (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae) Malacologia. 2007;49(2):383–392. doi: 10.4002/0076-2997-49.2.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsukura K, Tsumuki H, Izumi Y, Wada T. Changes in chemical components in the freshwater apple snail, Pomacea canaliculata (Gastropoda: Ampullariidae), in relation to the development of its cold hardiness. Cryobiology. 2008;56(2):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wada T, Matsukura K. Response to abiotic stress in Pomacea canaliculata with emphasis on cold tolerance. Philippine Rice Research institute: Philippine; 2017. pp. 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu GF, Yang QQ, Lin HF, Yu XP. Differential gene expression in Pomacea canaliculata (Mollusca: Gastropoda) under low temperature condition. J Mollus Stud. 2018;84:397–403. doi: 10.1093/mollus/eyy022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang XY, Zhou T, Chen BH, Bai HQ, Bai YL, Zhao J, Pu F, Wu YD, Chen L, Shi Y, Ke QZ, Zheng WQ, Chen J, Xu P. Identification and expression analysis of long non-coding RNA in large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea) in response to Cryptocaryon irritans infection. Front Genet. 2020;11:590475. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.590475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim YJ, Zheng B, Yu Y, Won SY, Mo B, Chen X. The role of Mediator in small and long noncoding RNA production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Embo J. 2011;30(5):814–822. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornienko AE, Guenzl PM, Barlow DP, Pauler FM. Gene regulation by the act of long non-coding RNA transcription. BMC Biol. 2013;11:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kung JT, Colognori D, Lee JT. Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics. 2013;193(3):651–669. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakhotia SC, Mallik M, Singh AK, Ray M. The large noncoding hsromega-n transcripts are essential for thermotolerance and remobilization of hnRNPs, HP1 and RNA polymerase II during recovery from heat shock in Drosophila. Chromosoma. 2012;121(1):49–70. doi: 10.1007/s00412-011-0341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang P, Hou Y, Fu W, Tao X, Luo J, Lu H, Xu Y, Han B, Zhang J. Characterization of lncRNAs involved in cold acclimation of zebrafish ZF4 cells. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195468. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0195468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun X, Zheng HX, Li JL, Liu LN, Zhang XS, Sui N. Comparative Transcriptome analysis reveals new lncRNAs responding to salt stress in Sweet sorghum. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:331. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kindgren P, Ard R, Ivanov M, Marquardt S. Transcriptional read-through of the long non-coding RNA SVALKA governs plant cold acclimation. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4561. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lucero L, Fonouni-Farde C, Crespi M, Ariel F. Long noncoding RNAs shape transcription in plants. Transcription. 2020;11:160–171. doi: 10.1080/21541264.2020.1764312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chekanova JA. Plant long non-coding RNAs in the regulation of transcription. Essays Biochem. 2021;65:751–760. doi: 10.1042/EBC20200090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su S, Liu J, He K, Zhang MY, Feng CH, Peng FY, Li B, Xia XM. Overexpression of the long noncoding RNA TUG1 protects against cold-induced injury of mouse livers by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation. Febs J. 2016;283(7):1261–1274. doi: 10.1111/febs.13660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji H, Niu CY, Zhan XL, Xu J, Lian S, Xu B, Guo JR, Zhen L, Yang HM, Li SZ, Ma L. Identification, functional prediction, and key lncRNA verification of cold stress-related lncRNAs in rats liver. Sci Rep. 2020;10:521. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57451-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ran MX, Li Y, Zhang Y, Liang K, Ren YN, Zhang M, Zhou GB, Zhou YM, Wu K, Wang CD, Huang Y, Luo B, Qazi IH, Zhang HM, Zeng CJ. Transcriptome sequencing reveals the differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs involved in Cryoinjuries in frozen-thawed Giant Panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) sperm. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:3066. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang P, Dai L, Ai J, Wang Y, Ren F. Identification and functional prediction of cold-related long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) in grapevine. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6638. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li L, Liu JH, Liang Q, Zhang YH, Kang KQ, Wang WT, Feng Y, Wu SH, Yang C, Li YY. Genome-wide analysis of long noncoding RNAs affecting floral bud dormancy in pears in response to cold stress. Tree Physiol. 2021;41(5):771–790. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpaa147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Zhu XS, Cai ZH. Tributyltin toxicity in abalone (Haliotis diversicolor supertexta) assessed by antioxidant enzyme activity, metabolic response, and histopathology. J Hazard Mater. 2010;183(1–3):428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu CH, Zhang Y, Ren YW, Wang HC, Li SQ, Jiang F, Yin LJ, Qiao X, Zhang GJ, Qian WQ, Liu B, Fan W. The genome of the golden apple snail Pomacea canaliculata provides insight into stress tolerance and invasive adaptation. Gigascience. 2018;7(9):giy101. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enriquez T, Renault D, Charrier M, Colinet H. Cold acclimation favors metabolic stability in Drosophila suzukii. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1506. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colinet H, Larvor V, Laparie M, Renault D. Exploring the plastic response to cold acclimation through metabolomics. Funct Ecol. 2012;26(3):711–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.01985.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin Z, Wu RS, Zhang J, Deng ZX, Zhang CX, Guo J. Survivorship of geographic Pomacea canaliculata populations in responses to cold acclimation. Ecol Evol. 2020;10(8):3715–3726. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quinn JJ, Chang HY. Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(1):47–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng D, Li Q, Yu H, Kong L, Du S. Transcriptional profiling of long non-coding RNAs in mantle of Crassostrea gigas and their association with shell pigmentation. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1436. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19950-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang J, Luo X, Zeng L, Huang Z, Huang M, You W, Ke C. Expression profiling of lncRNAs and mRNAs reveals regulation of muscle growth in the Pacific abalone, Haliotis discus hannai. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16839. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35202-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.do Amaral MCF, Frisbie J, Crum RJ, Goldstein DL, Krane CM. Hepatic transcriptome of the freeze-tolerant Cope's gray treefrog, Dryophytes chrysoscelis: responses to cold acclimation and freezing. BMC Genom. 2020;21(1):226. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6602-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dieni CA, Storey KB. Regulation of hexokinase by reversible phosphorylation in skeletal muscle of a freeze-tolerant frog. Comp Biochem Phys B. 2011;159(4):236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.dos Santos RS, Diniz LP, Galina A, da-Silva WS. Characterization of non-cytosolic hexokinase activity in white skeletal muscle from goldfish (Carassius auratus L.) and the effect of cold acclimation. Bioscience Rep. 2010;30(6):413–423. doi: 10.1042/BSR20090128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fields PG, Fleurat-Lessard F, Lavenseau L, Febvay G, Peypelut L, Bonnot G. The effect of cold acclimation and deacclimation on cold tolerance, trehalose and free amino acid levels in Sitophilus granarius and Cryptolestes ferrugineus (Coleoptera) J Insect Physiol. 1998;44(10):955–965. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu FQ, Xue HW. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in plant responses to environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42(10):2931–2944. doi: 10.1111/pce.13633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang TX, Zhao M, Qiu XB. Substrate receptors of proteasomes. Biol Rev. 2018;93(4):1765–1777. doi: 10.1111/brv.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Navarro-Yepes J, Burns M, Anandhan A, Khalimonchuk O, del Razo LM, Quintanilla-Vega B, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Franco R. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and autophagy: cell death versus survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;21(1):66–85. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.5837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen L, Wu T, Chen Y, Qiu YN, Zhu SL, Qi W, Wei W, Liu SH, Liu Q, Zhao YT, Wang RL. Effects of temperature stress on antioxidase activity and malondialdehyde in Pomacea canaliculata. Chinese J Zool. 2019;54(05):727–735. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Islam S, Rahman IA, Islam T, Ghosh A. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of glutathione S-transferase gene family in tomato: gaining an insight to their physiological and stress-specific roles. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kayum MA, Nath UK, Park JI, Biswas MK, Choi EK, Song JY, Kim HT, Nou IS. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression profiling of glutathione S-transferase (GST) family in pumpkin reveals likely role in cold-stress tolerance. Genes. 2018;9(2):84. doi: 10.3390/genes9020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Digel I. Primary thermosensory events in cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;704:451–468. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park JC, Lee MC, Yoon DS, Han J, Park HG, Hwang UK, Lee JS. Genome-wide identification and expression of the entire 52 glutathione S-transferase (GST) subfamily genes in the Cu2+-exposed marine copepods Tigriopus japonicus and Paracyclopina nana. Aquat Toxicol. 2019;209:56–69. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Denlinger DL, Lee RE., Jr . Low temperature biology of insects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hayward SAL, Manso B, Cossins AR. Molecular basis of chill resistance adaptations in poikilothermic animals. J Exp Biol. 2014;217(1):6–15. doi: 10.1242/jeb.096537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki S, Awai K, Ishihara A, Yamauchi K. Cold temperature blocks thyroid hormone-induced changes in lipid and energy metabolism in the liver of Lithobates catesbeianus tadpoles. Cell Biosci. 2016;6:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-016-0087-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Enriquez T, Colinet H. Cold acclimation triggers major transcriptional changes in Drosophila suzukii. BMC Genom. 2019;20:413. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5745-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kostal V, Korbelova J, Rozsypal J, Zahradnickova H, Cimlova J, Tomcala A, Simek P. Long-term cold acclimation extends survival time at 0 degrees C and modifies the metabolomic profiles of the larvae of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hodkova M, Berkova P, Zahradnickova H. Photoperiodic regulation of the phospholipid molecular species composition in thoracic muscles and fat body of Pyrrhocoris apterus (Heteroptera) via an endocrine gland, corpus allatum. J Insect Physiol. 2002;48(11):1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(02)00188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen SF, Zhou YQ, Chen YR, Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):884–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12(4):357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pertea M, Pertea GM, Antonescu CM, Chang TC, Mendell JT, Salzberg SL. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(3):290–295. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(5):511–U174. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang J, Feng Y, Ding X, Huo J, Nie W-F. Identification of long non-coding RNAs associated with tomato fruit expansion and ripening by strand-specific paired-end RNA sequencing. Horticulturae. 2021;7:522. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae7120522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song F, Chen Z, Lyu D, Gu Y, Lu B, Hao S, Xu Y, Jin X, Fu Q, Yao K. Expression profiles of long noncoding RNAs in human corneal epithelial cells exposed to fine particulate matter. Chemosphere. 2022;287:131955. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Q, Zhang Y, Guo W, Liu Y, Wei H, Yang S. Transcription analysis of cochlear development in minipigs. Acta Oto-laryngol. 2017;137(11):1166–1173. doi: 10.1080/00016489.2017.1341641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun L, Luo H, Bu D, Zhao G, Yu K, Zhang C, Liu Y, Chen R, Zhao Y. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(17):e166. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li W, Cowley A, Uludag M, Gur T, McWilliam H, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Lopez R. The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W580–W584. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kang YJ, Yang DC, Kong L, Hou M, Meng YQ, Wei LP, Gao G. CPC2: a fast and accurate coding potential calculator based on sequence intrinsic features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W12–W16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Song HM, Mu XD, Gu DE, Luo D, Yang YX, Xu M, Luo JR, Zhang JE, Hu YC. Molecular characteristics of the HSP70 gene and its differential expression in female and male golden apple snails (Pomacea canaliculata) under temperature stimulation. Cell Stress Chaperon. 2014;19(4):579–589. doi: 10.1007/s12192-013-0485-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kanehisa M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019;28:1947–1951. doi: 10.1002/pro.3715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Ishiguro-Watanabe M, Tanabe M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D545–D551. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yu GC, Wang LG, Han YY, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Fig. S1. Verification of the selected DEGs and DELs by qRT-PCR as compared with RNA-seq data. a: Ca0 vs Con0; b: Con24 vs Con0; c: Ca24 vs Ca0; d: Ca24 vs Con24. The gene marked red represents differentially expressed gene.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Fig. S2. KEGG enrichment analysis of co-location target genes of DELs in cold acclimation group after cold stress (Ca24 vs Ca0). “Rich factor” means that the ratio of the number of the genes in the specific subcluster and the number of genes annotated in this pathway.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S1. Quality control (QC) information for mRNA sequences in Pomacea canaliculata. Table S2. The list of candidate genes forqRT-PCR validation in Pomacea canaliculata. Table S3. The 2-△△Ct values of candidategenes for qRT-PCR validation in Pomacea canaliculata.

Additional file 4: Table S4. KEGG pathways with differentially expressed genes and target genes from differentially expressed lncRNAs in different groups

Additional file 5: Table S5. Significant GO classifications associated with target genes from differentially expressed lncRNAs and mRNAs in different groups

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary files Table S1 to S5 and Fig. S1 to S2 are available in the additional files.

Raw reads for the transcriptomic analysis have been uploaded on the SRA database from NCBI under the BioProject PRJNA788380 and will be available after publication.