Abstract

Navigating the recovery journey following a burn injury can be challenging. Survivor stories can help define recovery constructs that can be incorporated into support programs. We undertook this study to determine themes of recovery in a predominately rural state. Eleven purposefully selected burn survivors were interviewed using a semi-structured format. Consensus coding of verbatim transcriptions was used to determine themes of successful recovery. Four support-specific themes were identified. These included: using active coping strategies, expressing altruism through helping others, finding meaning and acceptance, and the active seeking and use of support. These themes could be incorporated into support programming and would help guide future survivors through the recovery period.

It is estimated that burn injuries result in 486,000 hospital visits and 40,000 hospitalizations annually across the United States, with the majority admitted to burn centers.1 Thanks to improvements in medical care, survival rates have steadily increased over the decades and now 98.6% of hospitalized burn patients survive.1–4 As treatment improves, more people survive devastating burns, and the need for psychosocial support has become ever more important.5,6

The memories from the burn injury along with the recovery can be a painful and traumatic process with lasting repercussions on psychosocial well-being.7 These injuries can result in scarring, limb deformities, or new disabilities, and have a lasting impact on family life, work, recreation, and social life.7–13 Despite these often life-altering injuries, the majority of survivors adjust and some even exhibit posttraumatic growth.11,14,15 Factors related to successful recovery have been a topic of much qualitative and quantitative research.14,16–22 Coping styles have been strongly linked to adjustment postburn. In particular, avoidant coping, along with occupation loss, current unemployment, and lack of participation in recreational activities, predicated maladjustment postburn.14 On the other hand, a large body of literature has suggested active or adaptive coping was associated with more successful recovery.17 Another influential factor in adjustment postburn injury is the presence of support. Emotional support, including social support from family, friends, and healthcare workers, has been cited as an essential factor in helping survivors with their psychosocial recovery and return to life.9,13,14,23 Peer support, either locally through the burn center or local burn foundation or nationally through the Phoenix Society, has been highlighted as a particularly powerful means of providing belonging, affiliation, a provision of hope, and perspective.22,24,25

As central as support is to recovery and growth after trauma, in rural, less densely populated states, there are many challenges in helping survivors get the assistance they may need.26–30 Despite the number of support options offered by our regional burn unit, attendance at support events has previously been reported as uniformly low with only 17% of survivors accessing local support options.26 Distance, lack of transportation, and lack of awareness remain barriers to participating in these support activities.26

As recovery from a burn injury can be a very individual journey with many influences, we sought to understand adjustment after burn injury in a diverse group of survivors from a large, predominantly rural Midwest state, with the goal of using those findings to help inform our healthcare providers and our psychosocial recovery programs. Additionally, we sought to investigate how self-identified rurality impacted support after discharge. We chose a qualitative method as this was the best method for eliciting rich descriptions of patients’ experiences.

METHODS

The current study recruited patients from a previously published survey study.26 In the previous study, the research team sent quality of life (QOL) surveys to 968 adult burn survivors who had received treatment at an American Burn Association (ABA)-verified regional burn center over the preceding 10 years. All 150 patients who completed the surveys were asked if they wanted to participate in a qualitative follow-up study and 67 volunteered. For the follow-up study, one researcher (S.B.) purposefully sampled for variation in gender, age at the time of burn, time since burn, TBSA burned, rurality (participant defined), distance from tertiary care center, peer support participation (defined as both informal and formal, local or national), mechanism of injury, level of education, and QOL range. After sampling, we did not associate the sampling characteristics with individual participants. We did not link any other survey or health record data to participants in the qualitative study.

Data Collection

Complete data collection information is reported elsewhere.31 During 2016, one researcher (S.B.) conducted 11 individual semi-structured interviews that lasted on average 60 min. Domains in the prospectively developed interview guide included injury and treatment experiences and physical and psychosocial recovery. S.B. conducted interviews in English at participants’ preferred locations (in the home (n = 6), in a private room (n = 1), by phone (n = 1), or in a private office at the burn center (n = 3). Verbal consent was recorded at the time of the interview. Audio recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

We uploaded transcripts into MAXQda,32 a qualitative data analysis management program. We conducted an iterative, team-based thematic analysis to develop themes and subthemes that categorized reported participant perspectives.33 Three team members (S.B., K.D., L.W.) independently coded all transcripts, and each transcript was also read by at least one additional team member to enhance coding comparability. In regular meetings, the team discussed each transcript and iteratively developed and refined a codebook of themes with definitions. We do not offer identifying information (eg, gender, age) with the quotations below to protect the privacy of study participants.

The study follows Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ).34 The local Institutional Review Board approved the study as Human Subjects Research.

RESULTS

Interviewee Characteristics

Participants included 7 women, 4 men, with diverse burn mechanisms (assault, accidents, and self-infliction, Table 1). During the study, interviewees’ ages ranged from 31 to 56, while their age at the time of injury was 4–56 years. Interviewee characteristics also varied in TBSA (from 0% to 15% to greater than 50%), time since burn (from 3 months to 26 years), and distance from the tertiary care center (15–135 miles at time of interview). Five identified as rural residents. Five had participated in organized burn peer support. Four became trained Survivors Offering Assistance in Recovery (SOAR) through the Phoenix Society, a national burn support society. SOAR providers are burn survivors who undergo special training by the Phoenix Society to provide support to other survivors. The interviewees differed from the larger population they were drawn from in terms of sex (more females) and time from their burn injury (more recent).

Table 1.

Participant demographics and burn injury data

| Variable | Number of Participants (11) |

|---|---|

| Age (at the time of interview) | |

| 25–39 | 2 |

| 40–54 | 4 |

| >55 | 5 |

| Years from injury | |

| 0–1.9 | 5 |

| 2–4.9 | 3 |

| 5–9.9 | 1 |

| >10 | 2 |

| Gender (female) | 7 |

| Race | |

| White | 9 |

| Black | 1 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Burn percentage | |

| 10–14.9 | 3 |

| 15–29.9 | 4 |

| 30–49.9 | 2 |

| >50 | 1 |

| Unsure | 1 |

| Married | 6 |

| Rurality* | 5 |

| Support use | 6 |

*Participant defined.

Emergent Themes

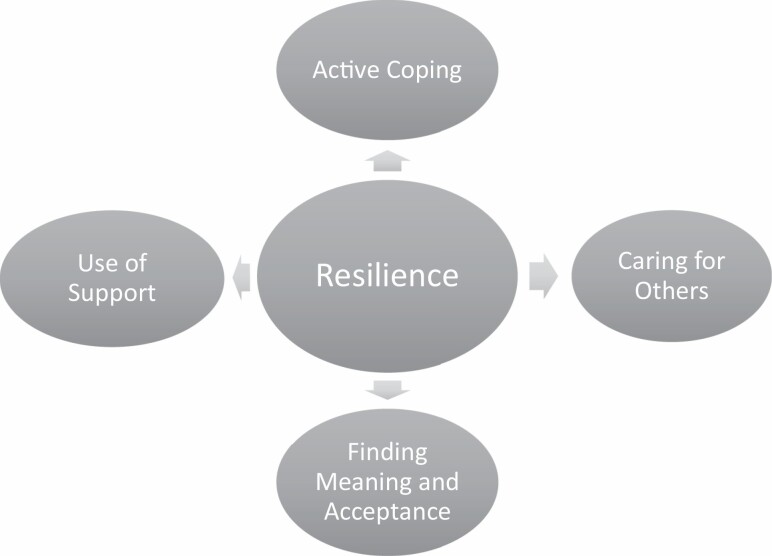

We identified four principal themes in survivors’ accounts linked to achieving resilience after burn injury: adaptive (or active) coping, caring for others, finding meaning and acceptance, and use of support systems (Figure 1). We also identified barriers to care and support, which were sometimes exacerbated for survivors who lived in rural areas.

Figure 1.

Themes contributing to survivor resilience.

Adaptive (Active) Coping

Survivors used various coping strategies throughout the recovery period to regain a sense of normalcy following their burn injury. Active coping was the most common coping mechanism; we identified active coping strategies in every survivor’s account. Through active coping, survivors found solutions to help perform activities of daily living (ADLs), assume control of their rehabilitation, and reimagine their burn narratives. Some strove to return to daily tasks (“Cleaning’s therapeutic for me [now]”) or to work, and some developed creative solutions to do so. One survivor with severe burns used chopsticks to wash her long hair by herself with one hand in the kitchen sink, rather than pay the nearby beauty school.

Goal setting enabled others to achieve a successful recovery. “Just being able to help out on the farm a little, weather permitting,” gave one survivor a feeling of independence and purpose. Another survivor of a large burn-related his overarching goal during recovery:

I just didn’t want to be stuck in a rehab place or an old folks home or havin’ somebody else taking care of me all the time. There was too many things that I didn’t think I had done yet that I wanted to do…. I can do my own thing here at home and I don’t have to have somebody takin’ care of me 24-hours a day.

Others worked hard to develop their own recovery plans and even to fill in the gaps of inadequate access to health care. For example, two survivors with limited or no access to therapy services took control of their own efforts to regain functional movement. One described, “I, on my own, started working with my hands, trying to make them move and everything.” Another, discharged from therapy after two sessions, kept working:

Ever since then, I’ve been doing them for 20 minutes a day … I’ve done it 42,000 times, 4,2000 minutes, already.

Retelling their burn injury story was central to many of the survivors’ journeys of healing. Telling their stories often was identified both as a form of support and a form of giving to others (as discussed further in the next section). One survivor and spouse trained and worked as SOAR volunteers believed volunteering “would help us too.” Others produced creative works of art. Multiple participants reported using poetry, painting, and writing, sometimes but not always addressing the injury.

I can get it out—how I feel. When I paint and draw, it makes me feel a lot better…. That’s my therapy. That’s how I cope with being burned.

Survivors also coped with their injury and disability by comparing themselves to other survivors and finding hope in seeing other survivors’ post-injury recoveries. For one survivor, this meant hoping his visible recovery could match that of a SOAR volunteer with a similar cause of severe injury. For others, seeing that other survivors could be happy, change careers, or have big plans helped them develop and escalate their own plans for recovery. For some survivors, learning about and meeting others with worse struggles encouraged them to accept new challenges. After attending World Burn Congress, one survivor gained the confidence to return to her job.

Well, listening to some of the stories how people got hurt and their recovery process… It was just more amazing to see the struggles people were coping with compared to what I had.

Another shift in attitude for a few survivors involved embracing their current abilities and trying new activities. One participant reported acting on a long-held family dream, camping:

I said, “This has been something we’ve been putting off forever.”… I said “One thing I’ve learned is you can’t keep putting things off, because something might happen.” Something did happen, so it’s like, let’s start doin’ that.

Caring for Others

Despite their sometimes overwhelming injuries, many survivors continued to identify their own ability to care for others. Many survivors spoke of how caring for others helped them find meaning and purpose or elevated their mood. Participants shared their skills, time, and lived experience, including knowledge of their own injuries and recovery strategies. For example, one participant continued to help fellow community members with computer problems or small physical tasks.

I try to take and make sure that I do things for the other people around, my neighbors, help them out as much as I can, [even] being limited. …that’s one of the happy things that I find, too, is to help people with the small problems.

As noted earlier, active coping for many survivors included sharing their stories with others, which they also perceived as caring for others. Four survivors became SOAR supporters helping and encouraging others along their recovery journey. The survivor and spouse who trained as SOAR volunteers felt the activity helped themselves as well as others: “To get our story out would make us feel better … besides helping the people we’re talking to feel better and know what they could expect down the line.” One participant who had been burned as a child wanted to share her experiences with other children by becoming a burn camp counselor.

I can show them what the future could possibly look like for them. I can show them how my scars have healed. I can show them the kinds of things that I do, and explain that this injury is not the stopping point.

Several survivors spoke about finding communities online and becoming active in those forums. These online communities might involve burn injuries or other shared experiences. Offering support, advice, or personal stories online was another way to help others. For example, one survivor participated regularly in an online mental health support group:

they [members] will put down a problem they had or sometimes they’re asking, “I’m feeling depressed. I quit taking my meds.” You just support them back… If my story can help somebody, and if my words of support can help someone? It makes me feel really good.

Finding Meaning and Acceptance

Finding meaning and acceptance involved attributions as to why the injury happened. In coming to terms with the injury, survivors had to often redefine themselves and their relationships with others and community. For the majority, this involved new limitations, often a greater dependence on others, and for some, a career change.

The power of finding a reason for their injury helped many, including these survivors, gain resilience.

I think that’s all God’s will right there, because [of] all the work that I do now, trying to help others. I’m scarred for life, and I use my scars to reach people … to show ‘em what can happen to you…, and reasons why you shouldn’t use drugs.

And in the words of another survivor:

I hope my injuries can bring some meaning to others, for kids. Sometimes I told the kids [who asked] “What happened to you?” … “Oh, I was burned very bad, so never, ever touch fire,” so they will know. It’s a painful ride.

Leaving established careers because of new disability was a painful process for some but the process of self-redefinition forced some to craft different professional trajectories that enabled them to successfully regain a sense of normalcy and fulfillment. For example, one participant could not continue his physical labor job, “a passion of mine for 15 years.” Drawing on alternative and newly developed skills, he turned his need to work from home into a new passion, becoming a respected advocate for addiction recovery.

For one participant, after surviving a major burn, other stressful events—a leaking roof, a flat tire—were less daunting: “It’s not like it used to be, [where I would worry] “Oh, what I’m going to do with this.” No. I just feel like, “Okay. That can be taken care of at some time [later].” Eventually, the survivors reported acceptance of their new post-injury reality, often using variations of the term, “It is what it is.”

…I always had hopes that yeah, it was going to look better…. Then, I thought, “well if it doesn’t, it’s just something I’ll have to learn to live with.” What are you gonna do?

…Sometimes it’s a struggle ‘cause you think you should be the way you used to be, be able to do the things you used to do and I still feel that way, but it’s just the way it is.

One participant who needed many surgeries over several years used the same words to describe a new acceptance of her current capabilities.

Now, gradually, [the] reality is this. I’m not able to do much [with the contracture]. … it’s different from how I used to be … [now], I would tell myself, “It is what it is. It is what it is.”

Many survivors spoke of striving to adapt and alter their viewpoint, to see themselves as survivors and victors instead of victims.

…there’s gotta be a reason why all this happened to me. Am I supposed to be doing something?

To be able to say, “I’m not a victim. I am a survivor,” and be able to correct people on that and educate them is actually a great thing to me…

Because if you can’t be something, then maybe you can be something else that’s similar to it, but stop asking, “Why me? Why was I burned?” Turn it into something maybe more positive…. [From] being a victim, become a victor.

Finally, identifying themselves as survivors and finding resilience in their recovery helped some survivors adjust to other difficulties.

I know I’m tough. I know I can drive myself to the hospital all burned up… Like I said, if I can survive fire, I can survive anything.

Support: Making It All Possible

All participants reported using diverse sources of support, both informal and formal (Table 2). The source of support varied according to the elapsed time since injury. Immediately after injury, the burn team provided support for the survivors. Survivors reported being more focused on their physical recovery. In the words of one of our participants, “life centered around my injury.” As more time elapsed, support came from others, often outside the burn community. Neighbors, community, and other mental health and medical communities were a source of both instrumental and emotional help. Five participants sought and received mental health support. Only 5 of the 11 survivors attended any organized peer support group. A few reported SOAR visits while they were admitted or in clinic, but many had not heard of local organized burn support activities or lacked the means to attend. The survivors who attended organized burn peer support groups spoke to the powerful experiences of meeting fellow survivors through programs such as burn camp, Phoenix Society’s annual World Burn Congress, yearly burn support meetings held around the state, and SOAR. These activities provided the survivors with a sense of belonging, inspiration, and hope. A survivor who was burned as a child described the difference burn camp made:

Table 2.

Types of support used

| Formal Support | Informal Support |

|---|---|

| Peer counseling/SOAR | Friends and family |

| Phoenix society | Community |

| Formal support groups | Faith groups |

| Chat groups | Healthcare providers |

| Burn center resource groups | Online searches |

| Burn camps | Books |

| Licensed mental health providers |

[Burn camp] … was the first time that I remember seeing kids that looked like me…. I thought I was the only kid in the world that had these scars…. Burn camp had such a profound effect on me because I was no longer alone.

Several participants described the inclusiveness of organized burn support events as a strength, for example when one survivor said, “I like that it’s so inclusive in terms of types of burns, percentage, age of survivors, even how long ago your injury was.”

Despite not all attending organized burn support activities, all survivors reported receiving some support after their injury. Instrumental support included rides to appointments, help with bathing or dressing changes, and assistance with yard work, chores, and meals. Neighbors and communities came together for many survivors. One rural survivor without nearby family communicated through a sign he would put up in the window to tell a neighbor he was okay or needed assistance. Another community gave a survivor a prominent role in a town celebration and various organizations raised funds for medical bills. Others were supported by employers or work colleagues who helped them by taking extra shifts or work duties.

Families provided the most intimate support, performing dressing changes, making adaptations to the house, and helping with ADLs such as feeding and bathing. Several other survivors also mentioned the crucial role of families over the long course of recovery and argued that family members needed support too.

It is a family affair… I feel there should be support groups for families.

One thing I think that could be better is having the more familial approach… I feel like a burn injury, especially in a pediatric family, is an entire nuclear family event.

Care and Support Barriers

Survivors reported barriers to accessing care and support, availability of support, the requirements of their physical recovery, and distance. Rural residence created additional barriers for survivors in accessing both care and support.

While all participants reported receiving informal support of some kind, several described having only one person—a spouse or partner—as social support. One participant related how her husband quit his job to take care of her, calling him her only support: “We were kind of our own support group. He was my support group … whenever I was crying or something.” Another survivor with limited ability described the dependency he had on his significant other for travel, which further constricted his ability to access support—and even healthcare:

‘Cause right now … she has to be with me pretty much everywhere I go. … if I have to go to a group, she would have to come, but if she doesn’t have the time, … her [work] schedule is different every week… It’s really been difficult to just go to my appointments sometimes.

Multiple participants described the strain of physical recovery as one obstacle in overall recovery, describing exhaustion, pain, and weight loss that made it more difficult to access healthcare or support. In the words of one survivor:

…the next day you would end up being so exhausted … [it] just got to the point we didn’t go anywhere anymore.

Several participants described multiple barriers related to support groups that were not local. One reported work and distance prevented attendance at twice-monthly support groups held “up there” (near the burn center) during the middle of the day, and closed the interview by saying “I wish there was more … local burn-survivor support groups, other than having to go all the way to [the burn center].” Some survivors received emotional support from non-burn groups such as groups for mental health disorders and other medical conditions. Access to mental health resources, however, was sometimes scarce.

For rural survivors, in particular, many of these barriers overlapped. Isolation appeared in recovery narratives especially for rural participants, usually as a complicating factor, though they often also described loving other aspects of their rural environments. For example, one participant described the impact of social isolation on mental health: “Sometimes when you’re up here by yourself you don’t interact with a lot of people and it might work on you a little bit.” In general, rural participants described the distance to medical appointments, follow-up, and rehabilitation services as obstacles, especially when travel tired them excessively early in recovery. Several rural participants reported living at least an hour from family members. They also noted that rural areas had limited opportunities for specialized burn survivor support or other medical follow-ups, and two rural participants reported not knowing whether burn support was available in the nearest small cities. One described acute physical and emotional exhaustion that eventually caused him to stop extensive physical rehabilitation at a distant clinic. Another stopped attending support events and even working as a volunteer due to the 2–3 hr drive to the burn center: “…it just got be such a struggle… It was just too far away.” Another postponed the intention to access support groups “up there” partly due to physical recovery needs:

…I haven’t had a chance to pursue the support groups… I’m more concentrated on getting my strength back… Then maybe I’ll go and see about that [support] then, right?

Similarly, while mental health resources were a barrier for many survivors, they were especially difficult to access for survivors who lived in rural areas. One rural survivor reported waits of 45 days or more for therapy appointments even in the two nearest small cities. Another used telehealth to see a mental health specialist in another state due to lack of local providers.

Discussion

In a previously published manuscript using these data, our research team found that following a burn injury, survivors reported persistent injury and hospital memories, long-lasting skin and mobility issues requiring adjustment, and sometimes lifelong impacts to their emotional and physical wellness.31 In this article we sought to better understand the adjustment postburn injury to be more fully able to support our burn patients during recovery. Recovery from the trauma of a burn injury is a complex and lengthy process. It requires the inner strength of the survivor to integrate the injury and its subsequent challenges and create a pathway to recovery. While recovery can be a unique and personal process influenced by personality types, cultural differences, pre-burn psychopathology, and existing social support, psychosocial constructs related to successful recovery have been identified through qualitative studies of burn patients, as reported in an integrative review.17 However, no studies focus on survivors living in rural areas. Uncovering these constructs is important to help inform and strengthen the recovery program in order to better assist the survivor in healing and establishing resiliency. Through semi-structured interviews with 11 burn survivors in a predominately rural state, we sought to determine how they used support during their recoveries. Four themes contributed to successful recovery: the use of active or adaptive coping, expressing altruism through caring for others, finding meaning and acceptance, and seeking, engaging, and receiving support. Nevertheless, barriers to accessing support existed.

On the journey to healing and achieving acceptance, the survivor must first overcome the adversities of their injury. Adversities may be physical, such as needing assistance with ADLs, or emotional, such as dealing with visible burn scars. Different forms of coping with trauma have been described and measured in burn survivors. Avoidant coping, such as substance abuse or denial, has been associated with worse adjustment than active coping and has been found to contribute to both depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in survivors.9,16,18 Adaptive or active coping, on the other hand, has been associated with more successful return to health. Adaptive coping involves a high use of emotional support, problem-solving strategies, and viewing the journey through an optimistic lens.17,21,35 Others have described active coping as the fight to stay strong and grow through reflections on the past events.35 Part of the fight is the struggle to return to as much normalcy as possible. For one of our participants, this meant not having to pay someone to wash her hair. The fight to stay strong also encompasses taking control of one’s own recovery, as with the participant who created his own physical therapy plan, practicing hand movements, and stretching his new skin. Our analysis also found another subtheme of active coping—reflection by means of creatively telling one’s own story. In fact, storytelling in various forms has become an integral part of the burn community.36 Writing about one’s own traumatic experience has been found to be beneficial, even though the process of reliving the experience and getting the words on paper can range from uncomfortable to traumatic.36

Comparing oneself to others was also important in coping for survivors in the current study. Survivors received hope when looking at others who “looked good” or had adjusted well despite their injuries. Sproul et al noted that hope was an important construct for adjustment following trauma.37 Interacting with other survivors who had adjusted despite overwhelming losses helped study participants put their injuries into perspective, providing them with courage to move on with their life after burn. Sanctioned, as well as informal and other unsanctioned support, such as online sources, played a critical role in the successful recovery of study participants providing them with new perspectives, comradery, and hope. As coping strategies can be taught, survivors should be educated on adaptive coping techniques. And, just as important, as peer and other support activities are important to teach and model successful coping, these should be provided to survivors as well as their families, and engagement should be encouraged.25 These should also be available and accessible in many platforms throughout the survivors’ journey.

Altruism through caring for others was also a central theme in our survivors’ recovery efforts. For the participants, performing acts of kindness or helping others in crisis was a means of connecting with others, giving back the help they received, and boosting confidence. Empathy, and a renewed sense of appreciation, for life have been previously reported in survivors who have experienced life-changing or -threatening injuries and have been previously described in successful adjustment.38 This concept of “helping others helps one’s self” was first described in Riessman’s helper-theory in 1965.39–41 The helper-theory is the phenomenon of peers aiding other peers with problems and finding improvement in themselves.40 In the current study four survivors became SOAR supporters, finding comfort in helping others navigate the post-injury journey. For many survivors in this study, helping others—whether in person or online—provided them with the opportunity to redefine themselves within their limitations after the burn injury.

Accepting their new limitations and redefining life after injury was pivotal in enabling the survivors in the current study to recapture life. This has been shown in trauma survivors with a new disability who found a new sense of purpose and control following their injury by finding personal meaning in their injuries.15,38 Several interviewees used their injuries as prompts to get out prevention messages or to inspire other survivors. One interviewee took great pride in guiding and coaching younger burn survivors at the annual summer camp.42 Achieving acceptance was often noted by the citing of the phrase, “it is what it is.”

Finally, receiving, seeking, and accepting support made recovery attainable. Support is essential to successful adjustment from a burn injury.9,14 With the knowledge of common stages in recovery from trauma, healthcare providers, supporters, and survivors can anticipate different support they may need throughout the recovery process.38 Initially, the focus is on physical needs, and the survivor and their support team are often numb and dissociated from the event. All survivors found practical support (such as transportation to clinic and rehabilitation appointments, housework, meal preparation, ADLs, such as bathing and wound care) was essential early on. As they progressed in their recovery, their needs of support changed to help them cope with their losses and harness strength to accept their new reality and adapt.38 Often far from others in areas lacking mental health access, many rural survivors specifically only had their families to lean on. Five survivors did access mental health providers but often these sessions were limited. Five participated in official burn support activities, such as SOAR visits, support groups, and the Phoenix Society’s World Burn Conference. However, multiple barriers to accessing healthcare and support existed, especially for rural residents. Telehealth may offer an important opportunity to improve access to care for all burn survivors. Additionally, the benefits of offering support through many platforms—including telehealth and online mechanisms—are especially important for rural residents who may have limited access to sources of support and lack the means to travel to services.

LIMITATIONS

The study design and methodology of this project have several limitations. First, the study interviewed 11 survivors, which is smaller than the average size of 22 in qualitative burn research studies.19 Despite this, the study population was similar in age and gender to the larger sample it was drawn from.26 Furthermore, the purposeful selection was used to establish a diverse group of survivors. It is possible that those who self-selected for this study had a more unique or successful experience than the typical burn survivor, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Burn size and visibility may also impact survivors’ coping styles. However, our study was able to identify strategies that did help this group of survivors during recovery. Additionally, as there can be rich variability within definitions of rurality, the experience of rural burn survivors could be further explored in future research. Our findings are applicable to adult burn survivors only. Children and adolescents may use different strategies to find resilience after burn injury. Finally, this study focused on successful strategies that helped survivors gain resilience and, as such, does not discuss other barriers or challenges that survivors face.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

This study emphasizes to multidisciplinary teams that treat burns that it is important to understand the stages of recovery in order to support the survivor throughout recovery. Survivors and families benefit from multiple coping strategies, particularly active coping, that can be taught and should be part of the recovery process. Opportunities for both giving back and participation in organized support activities need to be available throughout recovery and accessible in several platforms, and should be easily accessible to survivors, including those in remote areas who may be years post-discharge. For the survivor and their support team, successful recovery stories that give hope and provide optimism can promote resiliency and even growth.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr. Baldwin gratefully acknowledges the support of a Summer Research Fellowship from the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine medical school research program Development Office provided support for interview transcription. The University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002537) provided resources to support the qualitative analysis. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Iowa or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kimberly Dukes, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA; Center for Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation, Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Iowa City, Iowa, USA; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida/Ascension Sacred Heart, Pensacola, Florida, USA.

Stephanie Baldwin, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Florida/Ascension Sacred Heart, Pensacola, Florida, USA.

Evangelia Assimacopoulos, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA; Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Brian Grieve, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Joshua Hagedorn, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Lucy Wibbenmeyer, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa, USA; Department of Surgery, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 200 Hawkins Dr, Iowa City, Io, wa, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1. American Burn Association. Burn Incidence and Treatment in the United States. Burn Incidence Fact Sheet, 2016, accessed 10 Jan. 2018; available from http://www.ameriburn.org/resources_factsheet.php.

- 2. Brusselaers N, Hoste EA, Monstrey S, et al. Outcome and changes over time in survival following severe burns from 1985 to 2004. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:1648–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Engrav LH, Heimbach DM, Rivara FP, et al. Harborview burns—1974 to 2009. PLoS One 2012;7:e40086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng Y, Lin G, Zhan R, et al. Epidemiological analysis of 9,779 burn patients in China: an eight-year retrospective study at a major burn center in southwest China. Exp Ther Med 2019;17:2847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bayuo J, Wong FKY. Issues and concerns of family members of burn patients: a scoping review. Burns 2021;47:503–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wiechman SA, Patterson DR. ABC of burns: psychosocial aspects of burn injuries. BMJ 2004;329:391–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Esselman PC. Burn rehabilitation: an overview. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:S3–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fauerbach JA, Pruzinsky T, Saxe GN. Psychological health and function after burn injury: setting research priorities. J Burn Care Res 2007;28:587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA, Heinberg L, Doctor M. Visible vs hidden scars and their relation to body esteem. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004;25:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mackey SP, Diba R, McKeown D, et al. Return to work after burns: a qualitative research study. Burns 2009;35:338–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin L, Byrnes M, Bulsara MK, McGarry S, Rea S, Wood F. Quality of life and posttraumatic growth after adult burn: a prospective, longitudinal study. Burns 2017;43:1400–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pallua N, Künsebeck HW, Noah EM. Psychosocial adjustments 5 years after burn injury. Burns 2003;29:143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jain M, Khadilkar N, De Sousa A. Burn-related factors affecting anxiety, depression and self-esteem in burn patients: an exploratory study. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2017;30:30–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Browne G, Byrne C, Brown B, et al. Psychosocial adjustment of burn survivors. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1985;12:28–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin L, Byrnes M, McGarry S, Rea S, Wood F. Posttraumatic growth after burn in adults: an integrative literature review. Burns 2017;43:459–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Andrews RM, Browne AL, Drummond PD, Wood FM. The impact of personality and coping on the development of depressive symptoms in adult burns survivors. Burns 2010;36:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Attoe C, Pounds-Cornish E. Psychosocial adjustment following burns: an integrative literature review. Burns 2015;41:1375–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kildal M, Willebrand M, Andersson G, Gerdin B, Ekselius L. Coping strategies, injury characteristics and long-term outcome after burn injury. Injury 2005;36:511–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kornhaber RA, de Jong AEE, McLean L. Rigorous, robust and systematic: qualitative research and its contribution to burn care. An integrative review. Burns 2015;41:1619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lawrence JW, Fauerbach JA. Personality, coping, chronic stress, social support and PTSD symptoms among adult burn survivors: a path analysis. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003;24:63–72; discussion 62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willebrand M, Andersson G, Kildal M, Ekselius L. Exploration of coping patterns in burned adults: cluster analysis of the coping with burns questionnaire (CBQ). Burns 2002;28:549–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McAleavey AA, Wyka K, Peskin M, Difede J. Physical, functional, and psychosocial recovery from burn injury are related and their relationship changes over time: a Burn Model System study. Burns 2018;44:793–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rosenbach C, Renneberg B. Positive change after severe burn injuries. J Burn Care Res 2008;29:638–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Badger K, Royse D. Helping others heal: burn survivors and peer support. Soc Work Health Care 2010;49:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chedekel DS, Tolias CL. Adolescents’ perceptions of participation in a burn patient support group. J Burn Care Rehabil 2001;22:301–6; discussion 300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baldwin S, Yuan H, Liao J, Grieve B, Heard J, Wibbenmeyer LA. Burn survivor quality of life and barriers to support program participation. J Burn Care Res 2018;39:823–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Clark JJ, Sprang G, Freer B, Whitt-Woosley A. ‘Better than nothing’ is not good enough: challenges to introducing evidence-based approaches for traumatized populations. J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:352–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health 2015;129:611–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mohatt DF, Bradley MM, Adams SJ, Morris CD. Mental health and rural America: 1994–2005. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Office of Rural Health Policy. 2006. :1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heydarikhayat N, Ashktorab T, Rohani C, Zayeri F. Effect of post-hospital discharge follow-up on health status in patients with burn injuries: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2018;6:293–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dukes K, Baldwin S, Hagedorn J, et al. “More than scabs and stitches”: an interview study of burn survivors’ perspectives on treatment and recovery. J Burn Care Res 2021; 43:214–218. doi:10.1093/jbcr/irab062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. MAXQDA. 2020. VERBI Software, Berlin, 2019 [software]. maxqda.com.

- 33. Gibbs G. Analyzing qualitative data. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dahl O, Wickman M, Wengström Y. Adapting to life after burn injury—reflections on care. J Burn Care Res 2012;33:595–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Badger K, Royse D, Moore K. What’s in a story? A text analysis of burn survivors’ web-posted narratives. Soc Work Health Care 2011;50:577–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sproul JL, Malloy S, Abriam-Yago K. Perceived sources of support of adult burn survivors. J Burn Care Res 2009;30:975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salick EC, Auerbach CF. From devastation to integration: adjusting to and growing from medical trauma. Qual Health Res 2006;16:1021–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Badger K, Royse D. Adult burn survivors’ views of peer support: a qualitative study. Soc Work Health Care 2010;49:299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Riessman F. The helper therapy principle. Soc Work 1965;10:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Williams NR, Davey M, Klock-Powell K. Rising from the ashes: stories of recovery, adaptation and resiliency in burn survivors. Soc Work Health Care 2003;36:53–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kornhaber R, Visentin D, Kaji Thapa D, West S, Haik J, Cleary M. Burn camps for burns survivors—realising the benefits for early adjustment: a systematic review. Burns 2020;46:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]