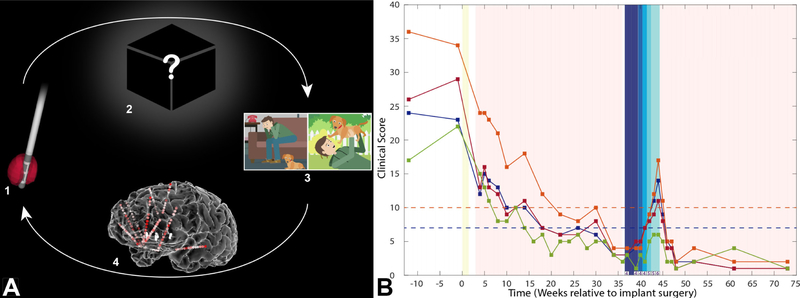

Figure 2. “Inverse” DBS programming strategy and clinical outcome.

A) The NMU recordings uniquely enable us to generate data-driven “Inverse” solutions for DBS programming. Selection of programming parameters in conventional DBS progresses in the “Forward” (upper arrow) direction: 1) Using a trial-and-error strategy, the clinician chooses different combinations of input stimulation parameters, including contact configuration, frequency, pulse width, and amplitude. 2) These parameters produce unknown changes in the brain, which in turn lead to (3) measurable behaviors (e.g., mood changes in the case of DBS for TRD). As described in the text, optimizing this Forward solution is challenging even in conventional DBS for TRD because of the mismatch in time constants and inconsistencies between programming adjustments and behavioral changes. Exploring the vast possible stimulation parameter space using this brute force approach is extremely time consuming and inefficient. Our trial uses NMU-derived intracranial recordings to pioneer the “Inverse solution” (lower arrow). The recordings allow us to measure and define various “network states”, electrographic patterns characterizing various mood states, and the network’s response to stimulation (4). Armed with this information, we can select a desired behavioral outcome (3), identify its associated network state (4), and then compute the combination of stimulation parameters (1) that are most likely to achieve it. This approach will become progressively more effective with future improvements in our understanding of brain-behavior relationships – in particular, the neural encoding of mood states. It is also readily translatable to a non-invasive future, as less invasive methods of network state measurement improve and can be substituted in (4). B) We tested the stimulation parameters derived from the NMU (yellow bar) during the outpatient open-label optimization phase (pink). Depression scores decreased steadily to remission (HAM-D<=7, blue dashed line; MADRS<10, orange dashed line). At week 37 the subject initiated the double-blind, randomized discontinuation phase. He was randomized to SCC discontinuation first. Stimulation amplitude was reduced from 100% to 0% in 25% increments per week (corresponding to shades of dark to light blue). Only the unblinded programmer knew the stimulation amplitude; the subject and remainder of the research team, including symptom rater, were blinded. For the first three weeks when stimulation was maintained at 100% (dark blue), the subject’s scores did not appreciably change, indicating lack of a nocebo effect that would have confounded interpretation. As amplitude was reduced over subsequent weeks his scores worsened, suggesting that his response to DBS was a true response, not a sham/placebo response. He met rescue criteria at week 44 (MADRS >25% increase and CGI-I [values shown along x-axis] of 6 [‘much worse’] relative to pre-discontinuation). At this point the discontinuation phase ended and unblinded stimulation resumed. VC/VS stimulation was not tapered, as dictated by our study protocol, to reduce risk to the subject (see Supplement). He again quickly remitted following DBS reinstatement. Abbreviations: HAM-A, Hamilton Anxiety Inventory (magenta); MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (orange); HAM-D, Hamilton Depression Inventory (blue); QIDS-SR, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self Report (green); CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement.