Abstract

Much is known about how experiences of community violence negatively affect youth, but far less research has explored how youth remain resilient while living in dangerous neighborhoods. This study addresses this need by analyzing in-depth, geo-narrative interviews conducted with 15 youth (60% Black, 27% Latinx, 53% female, 14 to 17-years-old) residing in low-income, high-crime Chicago neighborhoods to explore youths’ perceptions of safety and strategies for navigating neighborhood space. After carrying Geographical Positioning System (GPS) trackers for an eight-day period, youths’ travel patterns were mapped, and these maps were used as part of an interview with youth that explored daily routines, with special consideration paid to where and when youth felt safe. Drawing on activity settings theory and exploring youth voice, we find that experiences of community violence are commonplace, but youth describe how they have safe spaces that are embedded within these dangerous contexts. Perceptions of safety and danger were related to environmental, social, and temporal cues. Youth reported four overarching safety strategies, including avoidance, hypervigilance, self-defense, and emotional management, but these strategies considerably varied by gender. We discuss implications for practice and future directions of research.

Keywords: Community violence, gender, neighborhoods, perceptions, resilience, safety

Community violence proliferates in the lives and neighborhoods of a substantial portion of Chicago youth. Between 2015 and 2016, there was a 58% increase in homicide rates and 43% increase in non-fatal shootings, specifically concentrated in several disproportionately low-income neighborhoods on the south and west sides of Chicago (University of Chicago Crime Lab, 2017). In this paper, we consider how youth that live in high-crime communities navigate daily life, promote their own safety, and remain resilient while avoiding potential violent confrontation. While a plethora of research has detailed the many deleterious consequences of exposure to community violence (see Fowler et al., 2009 and McDonald & Richmond, 2008), considerably less work has examined where and how youth perceive safety and demonstrate strength while living in high-crime neighborhoods. Moreover, there is a need to integrate geospatial and qualitative research to provide an in-depth analysis of the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes through which youth perceive and respond to high-crime activity space (Mennis, Mason, & Cao, 2013). This study addresses these gaps by using an innovative methodological approach that integrates personalized maps of youths’ daily routines with in-depth interviews to explore daily behavior and perceptions of safety among a sample of 15 predominately Black and Latinx Chicago youth. Emergent in our analysis includes the intersubjectivity of safety, the importance of gender, and the nuance of how youth demonstrate resilience while living in the context of risk.

Perceptions of Safety

Perceptions are intersubjective, such that they are products of socially construed meaning and collectively constructed codes about the social context and those who inhabit it (Chiu, Gelfand, Yamagashi, Shteynberg, & Wan, 2010). Intersubjectivity shapes individual behavior due to the norms, rules, and codes that define the social ecology (Chiu et al., 2010). Activity settings theory describes intersubjectivity as constructed through the shared participation and meaning of routine activity, ultimately shaped by communities’ cultural context (O’Donnell, & Tharp, 2012). As such, how safety is perceived, experienced, or responded to, reflects the interplay of shared meaning, activity, and the social-historical context. These intersections have been exemplified in qualitative research exploring youth perceptions of violence and safety. Bennet Irby and colleagues (2018) found that perceptions of violence were linked to observed structural violence in the form of decrepit physical cues of the built environment, capitalistic exploitation of the community, and mental and physical health disparities. Additional qualitative work describes the duality of how safety perceptions are constructed in chronically violent settings, finding that adolescents perceived their communities as both “safe” and “unsafe” (Teitelman et al., 2010, p. 878). In Baltimore, adolescents perceived their neighborhoods to be predominately safe despite recognizing elements of danger (Zuberi, 2018). Elements that promoted safety include protective social ties, social control, and the sense of one’s ability to avoid danger, while perceived danger was associated with violence, being previously victimized, and the absence of social control (Zuberi, 2018). This dual reality of safety and danger may be attributed to perceptions of both positive and negative features of neighborhoods, reflecting the pluralism of neighborhood life (Witherspoon & Hughes, 2014).

The Importance of Gender

Perceptions of danger and safety may also be contingent on gender. Zuberi (2018) found that social control was most salient for girl’s perceptions of safety while violence and fighting implicated boys’ sense of danger. Witherspoon and Hughes (2014) found that girls were more likely than boys to report feelings of neighborhood connection (i.e., feelings of belongingness and identity) and collective efficacy (informal social control and trust). Qualitative research exploring youth risk management strategies found that girls appeared to be “shielded from neighborhood life” (Cobbina, Miller, Brunson, 2008, p. 884). This study found that girls perceived men and the nighttime as dangerous contexts and saw themselves as less physically capable to defend themselves, whereas boys more often perceived their residential neighborhoods as safe but perceived themselves to be the target of gangs, gun violence, and police harassment (Cobbina et al., 2008). Additionally, police presence and activity may be perceived as a risk or protective feature contingent on gender identity; for example, in New York City, Black and Latino boys viewed police harassment and involvement as a threat more often than girls (Rengifo, Pater, Velaquez, 2017).

Gendered perceptions of safety may reflect different experiences of violence and risk. Nationally, boys are more likely to be exposed to more physical forms of violence and are more likely to witness violence, while girls are more likely to be exposed to relational violence, sexual violence, and harassment (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, Hamby, & Kracke, 2015). However, in Chicago, one study found that rates of violence exposure were comparable across genders (Rasmussen, Aber, & Bhana, 2004) while another found that girls were more likely than boys to report accounts of violence in their daily routines (Richards et al., 2014). Rengifo et al (2017) found that boys’ perceptions of police were directly related to negative interactions and experiences of harassment. Understanding how gendered experiences of violence and risk may relate to youths’ perceived safety would be informative to tailor prevention or intervention strategies, particularly in how they inform youths behaviors and strategies to stay safe.

Safety Strategies and Resilience

Intersubjectively-derived and gendered perceptions of safety can implicate behavior and safety strategies. Safety strategies, also referred to as risk-management strategies, can be described as the ways in which youth strive to increase and maintain their emotional and physical safety while managing risks and perceived threats (Rengifo et al., 2017). In the context of high-crime neighborhoods, some common safety strategies include avoidance (i.e., avoiding places, people, or situations), hypervigilance (being hyper-aware to internal and external cues), and confrontive strategies (aggressive tactics; Cobbina et al., 2008; Rasmussen et al., 2004; Rengifo et al, 2017; Smith & Patton, 2016; Stodolska, Shinew, Acevedo, & Roman, 2013). Cobbina et al (2008) found that girls were more likely to avoid being outside at night whereas boys were more likely to carry weapons, and both groups were not likely to travel alone. Other research has found that avoidance is common across both genders (Zuberi, 2018), particularly avoiding being outside at night (Stodolska et al, 2013). In a sample of young adult Black males, Smith and Patton (2016) found high rates of hypervigilance, such as constantly being “on point” (p. 215). Additionally, boys engage in more confrontative coping strategies (Rasmussen et al., 2004), which may increase their risk for future violent victimization (Dong, Morrison, Branas, Richmond, & Weibe, 2019). This is particularly critical because previous research examining the consequences of chronic exposure to violence suggests that youth become desensitized over time, such that youth report less psychological distress (Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman, & Stueve, 2004), depression (Gaylord-Harden, So, Bai, Henry, & Tolan, 2017), and anxious/depressive symptoms (Kennady & Ceballo, 2016) while aggressive behavior increases linearly and exposure to violence becomes more chronic. Subsequently, it is important to examine perceptions of safety, safety strategies, and how they implicate behavior and daily functioning.

Safety strategies can represent skills and behaviors that youth actively employ to optimize development and promote normative functioning despite challenging circumstances. From this perspective, and despite their ramifications, safety strategies are examples of how youth exhibit resilience while inhabiting high-crime environments. Resilience refers to one’s capacity to overcome stressors and develop adaptive functioning despite adverse contexts (Jain & Cohen, 2013). Ungar (2013) proposes that resilience is characterized by bidirectional relationships between the individual and their environment that promote positive development; individuals must be able to access available, culturally relevant resources in order to thrive. Elements that promote resilience, such as individual and social resources or features of the environment, can all contribute uniquely to one’s capacity to overcome stressors. Importantly, resilience may not always appear in every domain of functioning, sometimes referred to as “ontogenic instability” or within-person variability (Wright, Fopma-Loy, & Fischer 2005, p. 1185). Additional work proposes that resilient processes can be conditionally adaptive, such that behaviors may not be adaptive in every social context, specifically when youth develop in high-risk environments and oppression (Gaylord-Harden, Barbarin, Tolan, & Murry, 2018).

Given the complexity of how resilience manifests itself in the context of risk and oppression, how does it function in the daily lives of youth who inhabit chronically high-crime neighborhoods? Sharkey (2006) puts forth the idea of “street efficacy,” or an individual’s perceived ability to avoid violent confrontations and stay safe in one’s neighborhood as a construct to describe this process. Sharkey (2006) found that neighborhood collective efficacy had a positive relationship with street efficacy, concluding that youth perceived themselves as more capable to handle potential violent conflict when they lived in neighborhoods where residents perceived greater control over the events that happened in their communities. In Ungar’s conceptualization, street efficacy is an example of resilience because it is a bidirectional, culturally relevant set of skills that youth actively employ to keep themselves safe. However, because resilience in the context of chronic community violence may be ontogenically unstable or conditionally adaptive, behaviors that promote competency or increase emotional safety may not “appear” resilient. As such, it is critical to examine youths’ perceptions of and responses to dangerous space in order to better understand how resilience manifests within these settings.

The Current Study

This study examines youth perceptions of high-crime neighborhood space in the context of daily routines and behavior to understand youths’ lived realities of community violence, their perceptions of safety and danger, and the strategies that they employ to stay safe. Working with 15 predominately Black and Latinx Chicago youth residing in high-crime south and west-side neighborhoods, we used personalized maps of youths’ daily routines in conjunction with in-depth interviews to gain a better understanding of how youth experience, perceive, and navigate space in the course of their daily lives. As a “geo-narrative” study (Kwan and Ding, 2008), the integration of geospatial and qualitative data moves beyond traditional self-report techniques to provide a rich account of youth daily life that is contextualized by both objective data (crime, GPS data) and subjective data (youth perceptions of their neighborhood environments; Mennis et al., 2013). Our analytic approach incorporates grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) and thematic coding techniques (Braun & Clark, 2006) to identify how youth perceive safety and practice safety strategies in the course of their daily life and activity space. This approach utilized inductive codes with an activity settings framework (O’Donnell & Tharp, 2012) to capture perceptions of safety and explore how youth habitually navigate high-crime environments while demonstrating resilience. Across our analyses, we payed special attention to the inherent strengths of youth and gender emerged as a distinctive element.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

A sub-sample of 15 youth participating in the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP) were recruited to participate in this study. The CSRP was a teacher training, socioemotional and behavioral intervention originally implemented in 2004 and 2006 with 602 preschool children and their families. Participants were recruited from 18 Head Start preschools located in seven of Chicago’s most disadvantaged neighborhoods (DaViera & Roy, 2019). Following the initial assessment, children and families have been assessed at seven additional waves with the most recent wave of data collection occurring in the spring of 2019. The sample of youth who were recruited to participate in this sub-study were recruited from the sample of youth who completed the sixth wave of data collection (N = 437) in 2017 when youth were on average in tenth and eleventh grades. We selected a random sample of 100 youths to recruit young people and identified 49 teens who were eligible to participate in the study (e.g., lived in Chicago). Via phone and email, research assistants contacted each youth and their parents until 15 youth were recruited. One youth declined to participate in the study, seven expressed interest but were eventually not recruited, and the rest were unable to be reached. Although the original intention was to select youth at random from the larger sample of eligible youth, youth who resided in relative proximity to the university where the interviews were conducted became prioritized to facilitate response rates. The final sample includes 53% female, 60% Black, 27% Latinx, average age of 16.22 years old; these demographics closely mirror the broader wave 6 sample (see DaViera & Roy, 2019).

This study took place between August and October 2017. Youth were given a Qstarz Q-1000XT Bluetooth Data Logger Geographical Positioning System (GPS) Receiver and asked to carry them at all times for a one-week (approximately eight day) period and were given $100 in renumeration to participate in all study activities. On the last day of the eight-day period two research assistants picked up the trackers and scheduled a time for youth to participate in an interview. Research assistants aimed to schedule the interviews within two to four days following the pick-up of the trackers, however 40% of interviews were conducted beyond a four-day period. During the period between the pick-up of the GPS tracker and the interview, each youths’ GPS data was geocoded in ArcGIS to create a map of where the youth had spent their time for each day that they carried the tracker. These individualized maps were then used during in-depth, semi-structured interviews with participating youth, conducted by two trained graduate student research assistants. Most interviews occurred at the university where the study was housed, with exception to a small percentage of interviews that took place at the participant’s home. During the interview, interviewers and participants reviewed each of the personalized daily maps through ArcGIS and participants were asked where they were at each point in time, how they arrived at that location, and what they were doing. The interview protocol was designed with an activity settings framework (O’Donnell & Tharp, 2012), focusing on youths’ routine behaviors and where and how youth spend their time during the data collection week. In addition, participants were asked to identify where they felt safe or in danger (e.g., “Where do you feel safest?”), and what safety strategies they habitually utilized (e.g., “What are some ways that you keep yourself safe?”). This process was repeated with each daily map for the entire period of GPS data collection.

There were some instances of missing GPS data, such as if a teen left the GPS logger at home and in one case, a participant lost the GPS logger. In such circumstances, interviewers used Google Maps and similarly asked participants to walk through each day during the data collection week using the maps as a visual aid. The majority of teens (73%) carried the GPS logger for the full eight-day period, 13% had only one day of missing data, and an additional 13% participants had more than one day of missing data.

Analytic Approach

Our analytical approach incorporated multiple techniques to synthesize both the GPS and interview data. To provide a contextual backdrop of the amount of crime occurring in the activity spaces of the youth in our study, we geocoded youths’ residential addresses and top five destinations, i.e., the places where youth spent most of their time during the data collection week, and linked these addresses to publicly available crime statistics obtained from the Chicago Data Portal (Chicago Data Portal, 2016, 2017). Violent crime includes all murder, rape, assault, robbery, and battery that occurred in the surrounding census tract in the 12 months preceding the data collection period. We then calculated the violent crime rate by taking the sum of all violent crime occurring exactly one year prior to the study and dividing that by the census tract population size (data obtained from the American Community Survey 2017 – Five Year Estimates) per 1,000 people. The result is total violent crime per 1,000 people. We compared these rates to Chicago’s average violent crime rate during 2017. In cases where there was missing GPS data, we used participants’ self-report of their daily routines and travel behavior to help identify the locations where participants spent the most time.

The primary goal of the qualitative analysis was to allow themes, codes, and relevant relationships to emerge from the interviews themselves while also enabling us to understand the results within the context of youths’ daily activity space. We chose to utilize a novel analytic strategy resulting in a multi-stage, iterative analysis that incorporated both grounded theory (Charmaz, 2006) and thematic analysis techniques (Braun & Clark, 2006). While purely grounded theory approaches are often used to build theory, we desired to understand our data with an activity settings lens; to this end, we used a constant comparative approach (i.e., comparing data at every stage of the analysis) applying inductively-derived codes which were then categorized by an activity settings framework (O’Donnell & Tharpe, 2012).

First, to fully grasp and become familiar with the data (Braun & Clark, 2006), a team of graduate- and undergraduate-level research assistants read each interview and generated several data displays including participant profiles and weekly schedules of where and how youth spent their time. This revealed how salient issues of safety and violence were for youth and gave us an orientation to develop initial codes of feeling safe, feeling in danger, exposure to violence, and safety strategies. Using segment-by-segment coding (Charmaz, 2006), two researchers then applied these codes to each interview using Atlas.ti (version 8.4.22.0). Coders routinely met to discuss data to compare and draw meaning from codes across and within interviews. This process was repeated until reliability was stable (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.92) and initial themes emerged.

Following this stage, we created inductive codes (i.e., codes generated from the data) to explore preliminary themes derived from the initial analysis and reanalyzed the interviews with focused coding (Charmaz, 2006). Focused coding is a process in larger chunks of data (e.g., all data coded with feeling safe) are re-analyzed with a more detailed codes with the goal of understanding and synthesizing themes. This generated numerous codes that strived to “unpack” the meaning of safety, including defining where and when safety or danger was expressed (e.g., nighttime), how youth felt in certain spaces (confident), with whom youth felt safe or unsafe (family), attitudes and beliefs about safety and violence (violence is unavoidable), and ways that youth promoted their own safety (hypervigilance). Two researchers collaboratively created and applied focused codes inductively to each interview, such that data was analyzed, interpreted, and discussed in conjunction. As these two coders worked on each interview in tandem, reliability testing was unnecessary. Again, we followed the constant comparative approach to analyze the relationships between initial and focused codes, comparing codes within and between interviews, and exploring where codes co-occurred or overlapped with others. We observed patterns that were most common across all interviews, as well as data that were inconsistent. The benefit of this approach included the ability to examine how initial and focused codes overlapped and co-occurred in patterns both relevant to the entire sample and those specific to certain groups, revealing the gendered nature of our data.

Drawing on thematic coding methods, we then recategorized this focused coding with activity settings theory (O’Donnel & Tharpe, 2012), finding that codes fell into four categories, contextual features (e.g. nighttime), emotions (confident), beliefs (violence is unavoidable) and behaviors (hypervigilance). By recategorizing the data and comparing the relationships of both initial and focused codes within and between interviews, we examined how each of the activity settings features interacted together to identity patterns on how safety is perceived, experienced, and habitually practiced by the youth in this study. Throughout the results sections, we compare and integrate qualitative and geospatial data, narratively describe the themes that emerged from this approach, and give examples of how codes interacted to produce these results.

Results

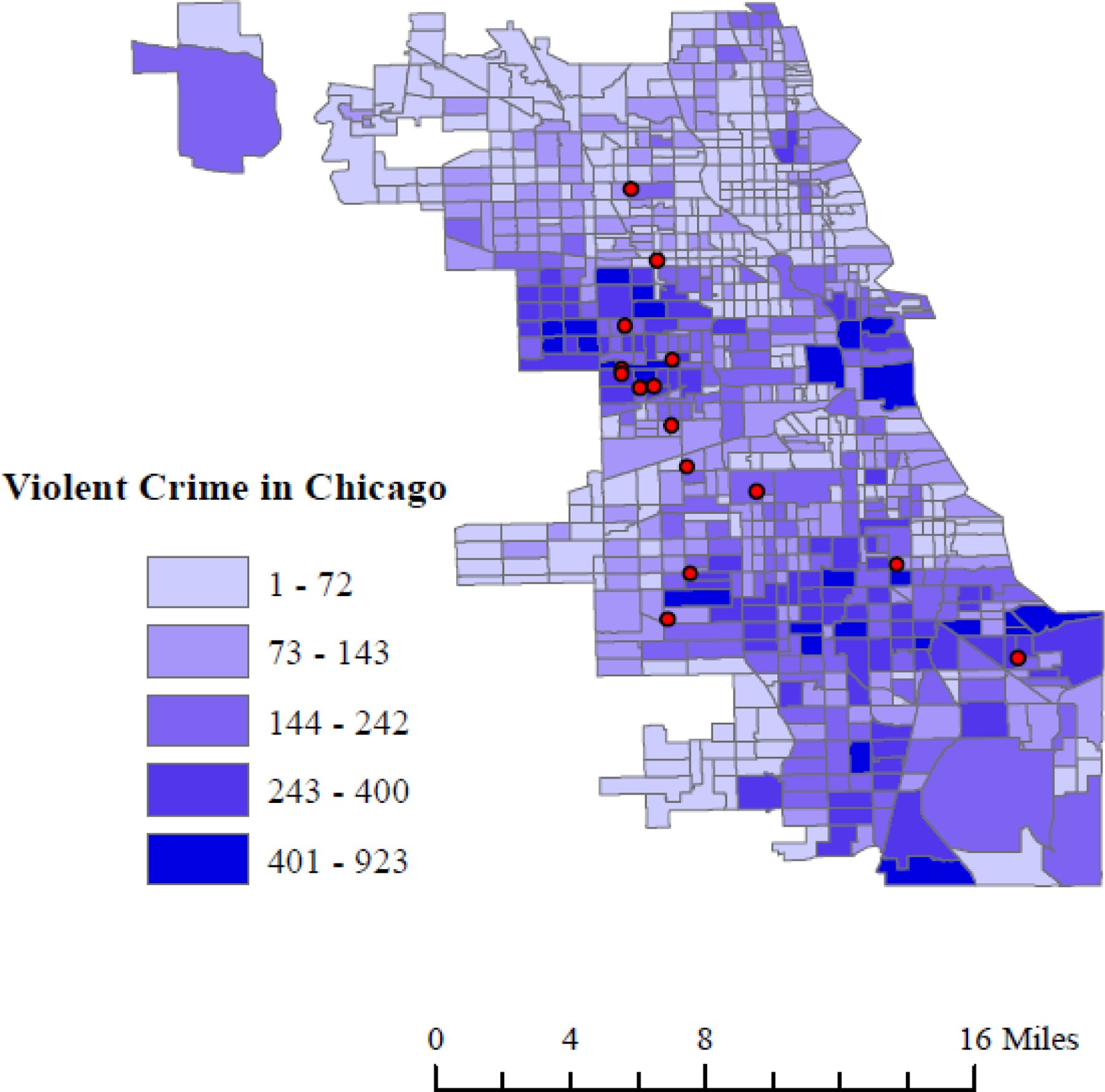

Figure 1 presents a map representing the level of violent crime occurring within Chicago census tracts in the 12 months preceding this study and the approximate locations of participating youths’ residential homes. We observed that youth were living in relatively high violent crime census tracts; the average crime rate across the sample’s activity spaces (i.e., top five destinations) was 67.69 violent crimes per 1,000 people whereas the average rate for Chicago was 37.23. Youths’ summative experiences of community violence, danger, and their respective safety strategies are displayed in Table 1. Experiences of community violence included self-reported feelings of danger in the neighborhood, awareness of violence (i.e., things youth knew or heard of happening but did not see or experience), witnessing violence, and direct victimization (i.e., being “jumped”). Only one youth did not report feeling in danger or experiencing violence. We identified four primary safety strategies that youth regularly employed, including avoidance, hypervigilance, self-defense, and emotional management. In the following sections we describe youths’ daily routines and highlight the commonalities, inconsistencies, and most salient experiences that emerged throughout our coding process. We observe the ways that gender differentially shaped youths’ experiences and the inherent strengths and skills of all youth.

Figure 1. Map of Chicago violent crime and youths’ residential addresses.

Note: This map displays all violent crime in the city of Chicago one year preceding the study duration. Approximate addresses of youth’s residential homes are indicated in red.

Table 1.

Sample summary

| Pseudonym | Experiences of community violence or danger | Safety Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Caleb(15BM) | Aware of gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Hypervigilance |

| Elena(17LF) | Did not mention violence or danger | Avoidance, Emotional Management |

| Shantay(14BF) | Witnessed a shooting, aware of violence and fights in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Hypervigilance, Self-Defense, |

| Pierre(16BM) | Aware of shootings and gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Emotion Management, Self-Defense |

| Fillip(16WM) | Experienced threats from people in the neighborhood | Avoidance |

| Catalina(15LF) | Aware of gang activity in neighborhood | Avoidance, Self-Defense |

| Labron(15BM) | Two friends to died due to shooting | Avoidance, Emotion Management |

| Oscar(15LM) | Was robbed at gunpoint, aware of gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Hypervigilance |

| Mackenzie(17BF) | Aware of violence, shootings, and gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Self-Defense |

| Deonte(17BM) | Was “jumped” in a park, friends have died due to shootings, aware of gang activity and shootings in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Emotion Management, Hypervigilance |

| Jalen(16BM) | Witnessed someone shot and killed, was chased by “thirty guys,” known people who have been killed due to shootings, aware of violence and gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Emotion Management, Hypervigilance |

| Daniel(15BRM) | Mother was “chased” in car, mother’s boyfriend was shot, father used to be in a gang, aware of violence and gang activity in the neighborhood | Avoidance, Hypervigilance |

| Alejandra(17LF) | Feels in danger in the neighborhood, did not mention violence | Self-Defense |

| Amelia(16BF) | Feels in danger in the neighborhood, did not mention violence | Avoidance |

| Karina(15BF) | Knows several people who have been killed, knows people currently in gangs, aware of violence, shootings, and gang activity in neighborhood | Avoidance, Self-defense |

Note: Next to pseudonym in parentheses are age, ethnicity (B = Black, L = Latino/a, W = White, BR = Biracial) and gender (M = male, F = female).

Youths’ Daily Life

Although this research focuses on youths’ experiences with danger and safety, it is important to keep in mind that this is only one aspect of youths’ multi-faceted lives. Over the course of the study, participating youth spent time at home, went to school, held part-time jobs, participated in summer/after-school programs, played sports and video games, and spent time with family, friends, and romantic partners. See Table 2 for a description of youths’ top five destinations including census tract-level violent crime rates corresponding to each location. While it is unsurprising that youths’ residential homes were unanimously the first top destination, it is relevant to observe how else youth spent their time; this was often at work, friends’ homes, or other family members’ residences. Importantly, many youths traversed several different neighborhoods beyond their residential boundaries throughout Chicago and the surrounding suburbs. Youths’ activity spaces are multidimensional, such that they habitually spend their time in multiple different neighborhoods with varying violent crime rates. Experiences with different spaces informed perceptions of safety. Mackenzie, who lived in a west-side neighborhood (first destination, 174.04 crimes per 1,000 people) but worked on the north-side (third destination, 7.43 crimes per 1,000 people), reported “I feel safest on the bus going to work... Like when I hit – when I start getting on the north side, I feel safest.” Meanwhile, some youth spent a substantial amount of time at home, which emerged as its own safety strategy. What is most evident from reviewing youths’ habitual routines is that their experiences with danger and safety were situated in the larger context of everyday teenage life.

Table 2.

Youths’ top five destinations and corresponding census tract level violent crime rates.

| Pseudonym | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caleb | Home (29.43) | School (21.53) | N/A1 | N/A | N/A |

| Elena | Home (22.48) | Work (77.50) | Beach2 (15.56) | Beach (36.73) | N/A |

| Shantay | Home (174.04) | Grandfather’s Home (98.33) | Work (101.08) | Friend’s Home (112.89) | N/A |

| Pierre | Home (179.89) | Aunt’s Home (101.08) | Football (174.04) | N/A | N/A |

| Fillip | Home (21.30) | Girlfriend’s home (13.37) | School (38.84) | N/A | N/A |

| Catalina | Home (38.50) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Labron | Home (96.65) | Friend’s Home (88.98) | Work (144.46) | School (98.33) | N/A |

| Oscar | Home (63.57) | Father’s home (36.14) | Work (19.75) | School (66.67) | Girlfriend’s home (16.46) |

| Mackenzie | Home (174.04) | Friend’s home (88.10) | Work (7.43) | School (16.98) | N/A |

| Deonte | Home (95.68) | Grandmother’s home (N/A3) | School (181.35) | Park (95.68) | N/A |

| Jaylen | Home (111.06) | YMCA (69.03) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Daniel | Home (37.11) | Father’s home (20.13) | Park (28.48) | Park (37.11) | N/A |

| Alejandra | Home (20.02) | Work (16.66) | School (23.15) | N/A | N/A |

| Amelia | Home (59.99) | Mother’s home (63.57) | School (64.38) | N/A | N/A |

| Karina | Home (88.98) | Work (60.27) | Friend’s home (52.06) | Park (85.14) | N/A |

Notes: The top five destinations are places where youth spent the majority of their time during the data collection week. Violent crime rates are in parentheses. Approximately one year preceding the study, Chicago’s average violent crime rate was 37.23 violent crimes per 1,000 residents; locations with higher violent crime rates than Chicago’s average are bolded.

N/A is in place if the participant did not have a top destination.

Places listed twice in the same row are two different locations.

This location was outside of Chicago.

Embedded Settings of Safety and Danger

Although the interview directly asked about youths’ perceptions of safety and danger, youth were never explicitly asked about their exposure to or awareness of community violence. Despite this, most of the youth in this study described experiencing violence in their daily lives. For example, Daniel described one of the local parks that he frequented (fourth destination, 37.11 crimes per 1,000 people):

Daniel: Well, just being there, you hear gunshots and stuff all the time. Every time I’m there, it’s like something happens – from people stealing stuff to people getting shot at… Right when I hear a gunshot, I just get to a close ground – which is like the playground – and I just lay down.

For teens like Daniel, this violence was common and extreme, directly inhibiting their sense of safety. However, feelings of danger were not omnipresent in youths’ discussions of their daily lives. In fact, a central theme that emerged from conversations with youth was that safe spaces were embedded in dangerous contexts. All youth identified at least one space where they felt safe within their neighborhoods, most often their home or school, despite also identifying the surrounding space as dangerous. Much of the emphasis in these conversations was on being inside a physical structure rather than being outside. For example, out of 171 quotes about “danger,” 25% of those quotes where co-coded with “outside.” Oscar reported: “School, it’s in a bad neighborhood, but inside it’s pretty much safe.” Similarly, Daniel described his school as safe but its location between two rival gang territories created a chronic sense of impending violence. Thus, while youth are embedded in multiple neighborhoods, safe and dangerous places are nested settings. The co-occurrence of safety and danger is further illustrated by Karina who holds concurrent perceptions of safety and danger in her home and surrounding neighborhood (first destination, 88.98 crimes per 1,000).

Interviewer: What about your house in particular makes you feel safe?

Karina: Because it’s not how we usually are. There’s not a lot of people who gangbang or shoot over there, as much as they used to. That’s part of it. It’s fixing a problem, but anywhere else, you have people who shoot a lot, do drugs, smoke weed, and just crazy. At any given time, we never know what can happen.

Interviewer: When would you say that you noticed a change in terms of feeling that your neighborhood is getting better in terms of not as many gang issues, or…?

Karina: That’s a tough question because somebody’s always dying. Especially where I live at…

For Karina, perceptions of safety and danger in her home neighborhood were directly influenced by experiences of the neighborhood both “getting better” and the violence that endured, nonetheless. Karina was not alone in this pattern; across all interviews, out of 73 quotes that were coded with “feeling safe,” 48% of the same segments were also coded with “danger.” Karina’s statement is a testimony to the nuance of safety and danger perceptions, driven by both positive and negative experiences in the community, and the uncertainty of impending violence.

Safety and Danger Cues: Unpacking Context, Emotions, Beliefs, and Behaviors

Nested spaces of safety and danger were defined by cues that youth would rely on to determine if a space was safe, or conversely, if violence might occur. Through an activity settings lens, we identified how contextual features, affective meanings, cognitive beliefs, and routine behaviors defined what safety and danger entailed. Familiarity, both a contextual feature and affective bond, was a sign of safety, while unfamiliarity signaled danger. For example, seeing an unfamiliar car was a danger cue for Jalen: “If the car was to go around the block three times in a row, that’s your cue to get out.” Whereas Daniel noted: “You have to remember what cars are in your neighborhood.” Elena, the only youth to not explicitly report neighborhood violence or danger, described how familiarity was an important reason why she felt safe in her neighborhood (first destination, 22.48 crimes per 1,000 people): I’ve lived there for a really long time, so I know the area really well. I know my neighbors. Pretty much my whole side of the street. I’m friends with a lot of people on my block, so it’s not like there’s anything too mysterious, I guess. Elena felt secure in her neighborhood because of the familiar ties she held in her community, yet familiarity alone was not an always assurance of safety in dangerous spaces. Deonte’s turbulent experiences with his local park (fourth destination, 95.68 crimes per 1,000) illustrates the tension when familiar spaces can also be unsafe.

Deonte: My friend that I grew up with, he got shot. He died. And at that park.

Interviewer: At that park where you play basketball?

Deonte: Yeah, I got jumped on at that park.

Interviewer: How long ago?

Deonte: Like two years ago. I haven’t been to that park in so long, I’ll just start hanging out with my girl most of the time because that was a wake-up call for me. Because that was the first time I got jumped on for no reason.

Despite his loss, experiences of violence, and awareness that the park was not safe, Deonte admitted that he felt comfortable playing basketball there, specifically during the day because he was so familiar with the park: “It was tough… I live, I was raised at this park.” The security of familiarity rested on feelings of belongingness, such as being with specific family and friends that helped the youth feel more comfortable. For example, safety was co-coded with family 27% of quotes and friends/romantic partners 23% of quotes. As Fillip stated, “With my friends, I feel like, even beyond safe, or more like just kind of untouchable.”

Whereas friends and family were two key indicators of safety, police and gangs were conversely indicators of harassment and danger. Labron stated, “Police are always harassing us for no reason,” and Amelia said, “If I was a boy, the police would probably harass me.” Daniel described that if he hears a shooting, he will not run because “bolting gets the cops attention” which might put him at risk for police violence. Regarding a police encounter that he had, Jalen said, “I don’t want to move… It’s sad to think like that, but then again, it’s not sad to think like that because you never know what can happen.” In addition, 47% youth explicitly described encounters with gangs or were knowledgeable about local gang territories, colors, and temporal patterns of operation. Catalina identified specific houses near her home that were dangerous because, “they’re gang related” and Karina knew gang-affiliated peers and described them as “more out of control than the people who did it before.” Daniel, whose father used to be in a gang, said: “It’s crazy, I guess. After a while, it sucks but it’s normal.” Many teens knew where and when gangs operated and relied on this information to stay safe.

The temporal organization of neighborhood activity was another key piece of information that youth used to determine whether specific spaces would be safe or dangerous. Fillip noted, “At night it’s definitely sketchier… Because that’s the time that people get wild.” Almost all youth reported that they felt less safe at night, with some teens noting that certain neighborhood locales are also dangerous in the middle of the day. Alejandra, whose work was her second top destination (16.66 crimes per 1,000), was mostly concerned when she traveled home (20.02 crimes per 1,000 people), by herself at night: If I’m coming home from work, and I take Pulaski, I have to walk a little more, but I have to walk alongside, I’m not sure if it’s Central Park, but it’s right next to the train tracks. There, there’s no streetlights, so it’s really, really dark. She continued to describe that she would feel safer if she was with people and would prefer to not take this route, but it was unavoidable given her work schedule. Like the nighttime, danger cues were often visually observable and related to elements of neighborhood disadvantage, such as abandoned buildings, the presence of homeless people, and public substance use. Karina described how her neighborhood changes at night.

Interviewer: Do you feel more or less safe based on the time of day, or who you’re with?

Karina: It depends. In the daytime, not really because I know a lot of people that hang around a lot of certain areas where I go. As far as nighttime, that would get to me because most of the time I go home by myself. So, there’s a lot of crack heads, crazy people, and gangbangers that just hang around the streets.

Safety Strategies and Demonstrating Resilience

Safety strategies were primarily behavioral routines that youth actively employed to increase physical safety, but some strategies also focused on regulating one’s perceptions and emotions as a method of sustaining a sense security. Four main strategies that emerged include avoidance, hypervigilance, self-defense, and emotion management. The following sections observe how safety and danger cues drive behaviors and youths’ responses to threats of safety.

Avoidance.

Avoidance was used as a strategy for staying safe by all but one youth in the study. This strategy was evidenced by youth spending a substantial amount of time at home during the data collection period. In fact, 13% of youth spent roughly the entire week at home and an additional 33% of youth spent at least half their week at home. With exception to going to a local YMCA (second destination, 69.03 crimes per 1,000), Jalen spent the entire data collection week at home (111.06 crimes per 1,000 people).

Jalen: If you know each and every day you could possibly go out and lose your life, why not take control of it? I go home. Once I come from school, I go straight to the crib... Don’t get me wrong, I’m not afraid to go outside; it’s just that I know what can happen going outside.

For teens like Jalen, staying inside was a strategic way to stay safe. Not all teens reported such highly avoidant behavior, but still knew where and when places should be avoided. This included both outside spaces such as parks and indoor spaces such as stores. Avoidance was also used for certain people or social cues, such as avoiding strangers and not making eye-contact. Some teens, particularly girls, noted that they would avoid boys, such as Amelia: “I try to avoid the bad people. I don’t like walking through groups of boys… I’ll cross the street.”

For some youth, avoidant behavior was encouraged by parents or family. Catalina, who spent the entire week at home, said: “First, I don’t like to go out, and second, my mom doesn’t let me out sometimes.” For other youth, avoidance as a safety strategy was something that youth described as preferring and did not attribute this behavior to parental or family rules. Nevertheless family, and particularly parents, were a strong source of support and guidance in youths’ efforts to stay safe. Some parents or family members helped youth travel safely around their neighborhood by driving them around or paying for commercial ride-shares. This was particularly important because nearly all youth in this sample did not drive or have access to cars and had to rely on other methods to travel.

For most youth, public transportation was necessary to get around but presented its own threats to safety. In fact, 26% of quotes about danger were related to taking public transportation. As such, many youths circumvented specific routes of travel or modes of transport as a strategy to stay safe. Amelia expressed that although it was unavoidable, she “Hates the bus. If somebody really, really strange gets on the bus… I get off the bus, wait for the next bus.” Much of Amelia’s fear was due to strangers or homeless people that would inevitably get on the bus, particularly on the routes that she had to traverse. She emphasized, “I wish I could avoid the bus.” Other youth found specific routes or times of the day when it was safe to travel and likewise strategized ways to manage their commute. Mackenzie said that she sticks to her usual route: “I just go on the route that I’m supposed to go and come back.” In contrast, Karina tried to avoid taking the same routes all the time: “I take different routes… I kind of zigzag my way home.” The commonality between these two different approaches was that travel behavior was effortfully managed in some way.

Hypervigilance.

Another common strategy, particularly among male youth (71% boys), was hypervigilance or a hyper-awareness to internal and environmental cues. This included specific behaviors to increase one’s ability to notice neighborhood cues, such as not wearing music headphones on public transportation, and general distrust of other people, particularly strangers. Shantay noted: “People can act at any given moment. I always stay in the back of everybody.” Caleb noted that he especially increases his attention to the environment when he takes public transportation: “I’m trying to hear and see everything.” Hypervigilant behavior also included having premeditated, detailed plans as to how youth spent their time, with whom, when, and specific travel plans as needed. For home-bound teens like Jalen, they would not leave the house unless they had detailed plans in place and knew that they would be safe. Therefore, hypervigilant and avoidant behaviors often coalesced to maximize feelings of safety and reflected perceptions of danger. For example, heightened attention to what was unfamiliar was a common safety strategy, such as by leaving a public space when one notices unknown people or cars.

In addition to hypervigilance towards external cues, 57% of boys also described heightened self-awareness, specifically in terms of how one appears to others, and effortfully managed their appearance. As Oscar described, “Just make sure I always wear my glasses… and then my haircuts – I usually make sure they don’t have any designs anymore…I just have to look clean.” The goal of maintaining and managing how one is perceived by others was closely tied to minimizing the perception of a threat. Oscar noted, “Everybody’s just always looking at you up and down.” Other forms of managing appearance included wearing certain colors, hairstyles, or clothes. Boys often reported wearing colors of local gangs to “blend in” with their neighborhood context, be perceived as familiar and thus, non-threatening. Oscar described how he also managed his appearance depending on his location and daily routine.

Oscar: Depending on what area because if I’m at home and I’m wearing black and red or they’re wearing black and red, it’s okay because most of the people there are – but at the same time, they think you’re with them… my dad – he always tells me, “Don’t worry. You’re wearing this color, they won’t mess with me.” Especially at my work, my uniform, I’m wearing a hat, a shirt, so they don’t really do much with that.

Oscar’s strategy of wearing local gang colors reduced potential threat from gang members’, but also perpetuated the perception of danger or risk of “strange interactions” by being perceived as gang-affiliated himself.

Self-defense.

Some youth described using self-defense strategies, although this approach tended to be more common among girls (63%) than boys. Often this relied on carrying some form of weapon including mace/pepper spray, pocketknife, or using house keys in self-defense. Pierre, the only boy to endorse self-defense as a strategy, said that he had taken boxing classes and could defend himself in that way. Fortunately, none of the youth reported having to use their weapons. As Karina stated, “I don’t really use it because nothing happens, but I like to keep myself safe because there’s a lot of crazy people in the world.”

Emotion management.

In addition to the specific behaviors that youth engaged in to keep themselves safe, it was also clear that some youth managed their emotions as a strategy for dealing with the violence in their lives, and this was most evidenced by boys. For example, 71% of boys in our sample described being emotionally unaffected in response to community violence or danger. Notably, no girls described this form of emotional management. Pierre, who previously lost two friends to gun violence, reported that he felt “nothing different” after their deaths and when he was asked if there were any places that he felt in danger, he replied, “Unh-unh,” despite the fact that each of his top five destinations contained high rates of violent crime (see Table 2). After Jalen described that a peer had recently been killed due to gang violence, he reported: I wasn’t shocked… I wasn’t crying or anything because I knew that one day, that was probably gonna eventually happen. Because he put himself in that situation. Jalen described this outcome as inevitable given his peer’s involvement in gang activity. Deonte, who spent a substantial portion of time inside the home during the data collection week, said: “I’m not the one that’s scared to go outside. I’m just saying it’s better for me to stay around my neighborhood and people I know.” Finally, Oscar described how he is not bothered by threats in the neighborhood: “I just know they’re trying to threaten me, but it’s not going to work.” These boys minimized their emotional feelings in response to situations of violence or danger, potentially as a strategy to maintain their emotional safety.

Despite the high levels of violence and danger the youth in our sample experienced, these youth maintained a positive view of themselves and these positive self-perceptions were related to their ability to deter violence and stay safe. Jalen prided himself on his safety strategies: I’m a smart guy. I’m not stupid; I know exactly what to do, when to do it, and what situation to do it in. Like Jalen, other teens shared this confidence in their ability to stay safe as an important part of their self-image. Elena, the only girl to describe a similar form of positive self-endorsement described herself as “observant person,” and for several boys, being “chill” was important, not only in terms of supporting their self-esteem, but also in promoting their sense of safety through a positive image and prosocial behavior. As Deonte aptly put, “I hadn’t been in a fight in three years. What am I fighting for?... I try to keep peace.”

Discussion

The findings of this study align with, enrich, and extend extant research on youths’ perceptions of and experiences in high-crime community space. Despite a relatively robust body of research demonstrating the negative effects of community violence on youth development (Fowler et al., 2009; McDonald & Richmond, 2008), comparatively little is known about how youth themselves perceive and navigate high-crime neighborhoods in the course of their daily lives. This work begins to address this gap in knowledge through the analysis of geo-narratives with a sample of young people residing in high-crime Chicago neighborhoods. Our findings reveled four major themes. First, despite high levels of violent crime and violence exposure, safe spaces are embedded in dangerous places. Youth identify and rely upon pockets of safety that exist within the broader, more dangerous context. Second, youths’ perceptions of space as either safe or unsafe were shaped by a complex interplay of experience, identity, environmental cues, and socially construed norms about the neighborhood. Thus, safe and dangerous spaces were intersubjectively constructed and youth relied on multi-faceted strategies to navigate neighborhood life. Third, these strategies to maintain their safety include avoidance, hypervigilance, self-defense, and emotion management and considerably differed across gender. Girls more often reported relying on self-defense strategies while boys reported more hypervigilance and were more likely to suppress negative emotions in response to violence or threats of danger. Fourth, our findings validate the nuanced ways that youth in our study exhibit resilience while residing in and navigating dangerous spaces, revealing how resilience is contextually conditional.

One of the most prominent themes that emerged from our data is that safe and dangerous spaces are embedded or overlapping, delineated by sociocontextual cues and the temporal organization of neighborhood activity. This finding upholds and extends why previous research has found that youth perceive both safety and danger in their neighborhoods (Teitelman et al., 2010; Zuberi, 2018) as well as positive and negative features (Witherspoon & Hughes, 2014). The importance of temporal organization of neighborhood space and activity has been observed in exemplar ethnographic research (e.g., Anderson, 1999; Burton & Prince-Spatlen, 1999) and supports the position that perceptions of safety and danger are intersubjectively constructed by the norms, rules, and codes of neighborhood life. This is critical to recognize because oftentimes neighborhood and community violence literature depict neighborhoods as unequivocally “bad” or “good” dependent on the physical characteristics present within their boundaries (Aber & Neito, 2000). This emphasis on structural disadvantage alone is incredibly narrow, ignoring both the fluidity and contextual nature of neighborhood space and the numerous strengths and resources that all types of neighborhoods have to offer. As youth navigate multiple neighborhood contexts within and beyond residential boundaries, with varying levels of crime, their perceptions of safety are informed by both positive and negative experiences. Moreover, neighborhoods do not have a bilateral continuum of safety but possess dynamic processes in which safety is constructed by community members, the roles, rules, and codes that define daily activity and neighborhood life.

Observable features of neighborhood space were important cues that youth used to determine if a space was safe or dangerous. These cues included environmental, social, and temporal features of space, highlighting the complex ways that youth must process information as they navigate neighborhood daily life. Echoing findings by Rengifo (2017) and Bennet Irby et al. (2018), many of these cues included features of economic disadvantage (i.e., homelessness), the presence of social supports (i.e., friends) or threats (i.e., gangs and police), and violence. Several of these cues have been associated as “situational triggers” for violent victimization among males (Dong et al., 2019); for example, being outside with friends during the day is a situational trigger for violent victimization, whereas being with friends outside at night is protective. Additionally, familiarity emerged as a powerful influence on perceptions of safety, and as such, may be related to neighborhood connection (i.e., feelings of belongingness and identity) which may be inhibited by perceived neighborhood problems (Witherspoon & Hughes, 2014). Our findings suggest that adolescents may feel connected and attached to their neighborhoods because of the familiar social and affective bonds that they hold while simultaneously recognizing the dual reality of safety and danger.

Perceptions shaped behavior and safety strategies in decisive ways. Similar to previous research (Zuberi, 2018), avoidance techniques were the most common safety strategy used across both genders. While several youths traversed multiple neighborhoods and areas of the city, others spent a substantial amount of time at home, and for some youth this was explicitly motivated by the desire to stay safe. Indeed, fear of crime and perceived danger are barriers to physical activity and being outside (Molnar, Gortmaker, Bull, & Buka, 2004; Stodolska et al, 2013), which may explain why perceived neighborhood disorder is associated with increased obesity (Dulin-Keita, Thind, Affuso, & Baskin, 2013). Relatedly, managing one’s travel was another approach common across genders particularly when it came to public transportation, and youth relied on knowledge of when and how it was safe to travel, often avoiding certain times of day, modes of transportation, and transportation routes. Previous research has found that youth feel less safe when traveling on public transportation in comparison to traveling by car (Wiebe, Guo, Allison, Anderson, Richmond, & Branas, 2013). However, given that public transportation is often necessary for urban dwelling youth to be mobile and independent, practicing avoidance while traveling was required to feel safe.

While some safety strategies were employed by both boys and girls, others were clearly gender-specific. Boys were more likely to engage in hypervigilant behaviors than girls and this hyperawareness manifested as appearance management for the purpose of reducing others’ perceptions of threat. Interestingly, this finding was similar to Rengifo et al (2017) which found that boys similarly managed their appearance to protect themselves from police involvement. Our data shows that boys strived to look “clean” or they tried to homogenize with the social context by wearing colors of the local gang. Although wearing colors of the local gang allowed them to “blend in” and be perceived as nonthreatening, this could also be reproducing community perceptions of danger or perceived endorsement of gang culture. That is, by perceiving danger cues (i.e., gang colors) and reacting to them in ways that increase perceived safety (i.e., wearing the same colors to appear nonthreatening), boys may be contributing to a cycle in which other community members perceive danger and react similarly. Comparatively, while girls did not describe managing their appearances in this way, they specifically avoided boys and engaged in more self-defense safety strategies. This is potentially problematic given that this approach can be a confrontational coping mechanism which has been linked to higher risk of victimization and delinquency (Dong et al., 2019) and has been described as “pseudo-effective” because it concurrently increases feelings of safety (Rasmussen et al., 2004, p. 72). It may be that girls were more likely to use self-defense strategies than boys because of increased risk and fear of sexual violence (Finkelhore et al., 2015; Stodolska et al., 2013).

Another interesting gender differential that emerged was in terms of boys’ emotion management in response to incidents of violence or danger. This may appear as emotional desensitization, in line with the pathologic adaptation model (Ng-Mak et al., 2004). As gender plays a significant role in the types and chronicity of violence exposure (Finkelhore et al., 2015) and the safety strategies that youth use (Cobbina et al, 2008), additional research should consider the role of gender in emotional desensitization. In this study, boys’ tendency to feel emotionally unaffected by violence and danger was a strategy to increase feelings of safety. It appeared that desensitization is a conscious process in which boys modulate or dampen emotional responses in order to be “prepared” for the anticipated stressors associated with chronic violence. A recurrent finding across both genders was the struggle to avoid violence and danger while simultaneously feeling that neither could be fully avoided. Thus, desensitization may be immediately adaptive to the perception that violence is unavoidable and may help adolescents cope with the pluralism of embedded safe and dangerous settings.

Boys’ modulation of emotion may also reflect gendered expectations of coping behavior. That is, desensitization may reflect masculine expectations of how boys “should feel” after exposure to traumatic stress such as violence. Previous research suggests that boys may exhibit hypermasculinity in the form of an absence of fear as a coping strategy which may be a method of maintaining a positive self-image (Spencer, Fegley, & Seaton, 2004). As a result, boys may be reluctant to admit being afraid or feeling unsafe. Research on adolescent’s perceptions of fear proposes that girls are socialized to more willingly to admit being afraid (Burnham, Lomax, Hooper, 2012). Thus, researchers must consider what exactly they are measuring when operationalizing desensitization, and whether these phenomena reflect gendered expectations of coping behavior or how gender is produced in the context of extreme neighborhood violence.

Youth relied on their own skills, personal attributes, and knowledge of neighborhood norms to be safe. In this sense, these strategies were all examples of resilience and street efficacy as they are culturally relevant, accessible skills that youth used to stay safe and avoid violence. However, it is important to recognize that resilience and efficacy are contextually dependent and the protective value of certain behaviors in some spaces may not carry over into other spaces. Appearance management is an example of street efficacy as it strengthens male adolescents’ perceived ability to avoid gang conflict. Yet, as many boys noted, wearing those colors in a different neighborhood would put them at increased risk for gang violence. Likewise, appearing gang-affiliated may also put youth at increased risk for police involvement or harassment (Rengifo et al, 2017) and may not promote optimum functioning in non-violent contexts such as school or the workplace. Gaylord-Harden and colleagues (2019) propose that such behaviors are conditionally adaptive, such that they promote the developmental competencies required to traverse risky contexts but that these benefits may not carry on into alternative situations. Our study upholds this notion by proposing that adolescents navigate dangerous spaces in ways that are immediately adaptive, increasing one’s sense of physical and emotional security.

Given these implications, this study suggests that researchers, practitioners, and others should recognize the nuanced ways that youth develop resilience in the context of danger and risk, uniquely reflecting the norms and codes of their social ecology. Subsequently, our theories of resilience must be contextualized to the normative successes and challenges of youth daily life and the cultural norms of their environment. How resilience manifests for a youth living in a low-crime, advantaged neighborhood is likely very different than resilience of a youth living in the context of extreme violence and adversity. Behaviors that promote adaptive functioning in dangerous contexts may not “appear” resilient despite the notion that they are grounded in a sociocultural reality that necessitates their practice. For example, appearance management may make a boy seem to be gang affiliated, and weapon carrying might put a girl at risk for violent confrontation, yet both represent practices that Chicago youth employ to maintain a level of emotional safety that they require to function throughout their daily lives. As such, researchers and practitioners should be careful to guard against their own biases and judgements before trying to understand what resilience “looks like” for a teenager living in a “bad” neighborhood. This nuanced understanding should reflect not only the theories that we employ, but methodological and analytical approaches should strive to incorporate this context.

Limitations

Despite its’ numerous strengths, this study also has several limitations that should be noted. First, like many studies, these findings may not generalize beyond Chicago, which historically struggles with gangs, gun violence, and poor police-community relations. We encourage other researchers to investigate youth perceptions and strengths in other locations, both urban and nonurban. Secondly, youth were interviewed by two white, female graduate students and given the fact that most youth in this study were nonwhite, this differential might have biased responses to interview questions or made youth feel less comfortable to discuss issues of safety in their neighborhoods. Third, we did not explicitly ask youth to report on their experiences of violence. Instead, youth offered this information when asked to describe safe and unsafe places in their neighborhoods and the strategies that they employ to stay safe. The fact that youth reported such experiences without prompting is a testament to the pervasive and enduring nature of violence that exists in their communities. Future research should continue to explore how multiple forms of violence and levels of victimization are related to safety perceptions and behavior. Additionally, while the incorporation of GPS data was a major strength, it introduced several challenges, such as if a youth left their GPS tracker at home which rendered our data subject to recall bias. This undoubtedly diminished the strength of our geo-narratives, but it is noteworthy that this was a generally less common occurrence. The integration of GPS data with interviews also increased the analytic and time demands on the research team. Mapping each participants’ GPS data within a relatively short time frame required dedicated support from a researcher skilled in GIS mapping methodologies. One last limitation of this research is its inability to examine intersectionality due to the sample and interview structure of this study. Intersectionality refers to the ways in which multiple social identities and positionality coalesce to shape one’s experiences of the world (Crenshaw, 1991). Despite this limitation, we did find that youths’ perceptions and behaviors differed across boys and girls in this study. Therefore, future research should employ intersectional perspectives to explore how an individual’s identity-driven experiences, the neighborhood’s identity, place-based stereotypes, or sociohistorical contexts merge to produce safety perceptions, strategies, and the antecedents of these interactions (Roy, 2018).

Implications

Researchers and practitioners should consider how to capitalize on youths’ strengths and experiences to empower them and build safer communities. Programs aimed at promoting youth well-being should include opportunities for physical activity and socialization but must also consider the local context as experienced by youth. Therefore, we encourage researchers and practitioners to leverage youth-led participatory methods when designing and tailoring community-based services. Not only do youth know where and when neighborhood spaces are safe, but participatory and action-orientated methods of youth engagement may be particularly appropriate for violence exposed youth (McCrea et al., 2019). One such exemplar program is the Youth Empowerment Solutions for Peaceful Communities (Zimmerman et al., 2011), which leverages participatory practices to build cultural and community pride, enhance safety and positive perceptions of communities, and reduce violence in chronically violent settings. This program and others that focus on community engagement, with special attention paid to trust, transparency, commitment, and communication, are critical to support youth and their communities (Morrel-Sanuels, Bacallao, Brown, Bower, & Zimmerman, 2016). Additionally, prevention and intervention strategies aimed at supporting youth safety should consider gender. Girls would likely benefit from safety programming such as Safe Dates (Foshee et al., 2014) that focuses on prevention of sexual harassment and dating violence to reduce girls’ weapon carrying. As boys may consciously modulate emotional responses to threats of safety, it may be critical to give these youths alternative, adaptive avenues for emotional expression, such as arts-based prevention/intervention approaches (e.g., The Truth N’ Trauma Project, Harden et al., 2015). Lastly, we found that police harassment was a source of stress and danger for boys. Poor police relations have been well documented as a source of critical stress for ethnic/minority adolescents and these experiences are both gendered and racialized (Brunson, 2007; Brunson, & Miller, 2006). The harassment observed in this study may reflect local policing policies in Chicago, such as the use of the “gang database” which disproportionately “tracks and targets” Black and Latino male youth (Policing in Chicago Research Group, 2018). Therefore, we encourage researchers to investigate the role of police and policing strategies regarding how they promote or inhibit feelings of safety in chronically violent settings.

Conclusion

This study addresses important gaps in the literature by investigating what safety means and how it is experienced by a sample of resilient Chicago teenagers living in high-crime neighborhoods. We find that safe spaces indeed exist within broader, more dangerous contexts and youth demonstrate strength in ways that may not appear resilient. Our data underscores how the effectiveness of youth resilience and safety strategies is contextually conditional; that is, the setting and collectively constructed community norms determine what behaviors demonstrate resilience and which could impose risk.

Funding:

This research was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, under Grant KL2TR002002. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: The authors of this manuscript have complied with APA ethical principles in their treatment of individuals participating in the research described in the manuscript. The research has been approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

References

- Aber MS, & Nieto M (2000). Suggestions for the investigation of psychological wellness in the neighborhood context: Toward a pluralistic neighborhood theory. In Cicchetti D, Rappaport J, Sandler I, & Weissberg R, (Eds.), The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents (pp. 185–220). Washington, DC: CWLA Press [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E (1999). Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York: W.W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Irby M, Hamlin D, Rhoades L, Freeman N, Summers P, Rhodes S, Daniel S, (2018). Violence as a health disparity: Adolescents’ perceptions of violence depicted through photovoice. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(8), 1026–1044. DOI: 10.1002/jcop.22089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett G, McNeill L, Wolin K, Duncan D, Puleo E, & Emmons K, (2007). Safe to walk? Neighborhood safety and physical activity among public housing residents. PLoS Med, 4(10), 1599–1607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V and Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2). pp. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson R, (2007). “Police don’t like black people”: African-American young men’s accumulated police experiences. Criminology & Public Policy, 6(1), 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson R, & Miller J, (2006). Gender, race, and urban policing. Gender & Society, 20(4), 531–552. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham J, Lomax R, & Hooper L, (2012). Gender, age, and racial differences in self-reported fears among school-aged youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(2), 268–278. DOI 10.1007/s10826-012-9576-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L, & Prince-Spatlen T, (1999). Through the eyes of children: An ethnographic perspective on neighborhoods and child development. In Masten A (Ed) Cultural processes in child development: The Minnesota symposia on child psychology, volume 26 (pp. 77–96), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K, (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Data Portal. (2016). Crimes- 2016 [data-file]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Crimes-2016/kf95-mnd6

- Chicago Data Portal. (2017). Crimes- 2017 [data-file]. Retrieved from https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Crimes-2017/d62x-nvdr

- Chiu C, Gelfand M, Yamagashi T, Shteynberg G, & Wan C, (2010). Intersubjective culture: The role of intersubjective perceptions in cross-cultural research. Perspectives on Psychological Science 5(4) 482–493, DOI: 10.1177/1745691610375562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbina J, Miller J, & Brunson R, (2008). Gender, neighborhood danger, and risk-avoidance strategies among urban African-American youths. Criminology, 46(3), 673–709. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- DaViera AL, & Roy AL, (2019), Chicago youths’ exposure to community violence: Contextualizing spatial dynamics of violence and the relationship with psychological functioning. American Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Morrison C, Branas C, Richmond T, & Weibe D, (2019). As violence unfolds: A space–time study of situational triggers of violent victimization among urban youth. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 1–34, 10.1007/s10940-019-09419-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin-Keita A, Thind H, Affuso O, & Baskin M, (2013). The associations of perceived neighborhood disorder and physical activity among African American adolescents. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finklehor D, Turner H, Shattuck A, Hamby S, & Kracke K, (2015). Children’s exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: An update. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from www.ojp.usdoj.gov [Google Scholar]

- Fowler P, Tompsett J, Jacques-Tiura A, & Baltes B (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and psychopathology, 21, 227–259. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden N, Barbarin O, Tolan P, & Murry V, (2018). Understanding development of African American boys and young men: Moving from risks to positive youth development. American Psychologist, 73(6), 753–767. 10.1037/amp0000300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden N, So S, Bai G, Henry D, & Tolan P, (2017) Examining the pathologic adaptation model of community violence exposure in male adolescents of color. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(1), 125–135. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1204925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden T, Kenemore T, Mann K, Edwards M, List C, & Martinson K, (2015). The Truth N’ Trauma project: Addressing community violence through a youth-led, trauma-informed and restorative framework. Child Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32, 65–79 DOI 10.1007/s10560-014-0366-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, & Cohen A, (2013). Fostering resilience among urban youth exposed to violence: A promising area for interdisciplinary research and practice. Health Education and Behavior, 40(6), 651–662, DOI: 10.1177/1090198113492761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennady T, & Ceballo R, (2016). Emotionally numb: Desensitization to community violence exposure among urban youth. Developmental Psychology, 52(5), 778–789, 10.1037/dev0000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan M, & Ding G, (2008). Geo-Narrative: Extending geographic information systems for narrative analysis in qualitative and mixed methods research. The Professional Geographer, 60(4), 443–465 [Google Scholar]

- McCrea Y, Richards M, Quimby D, Scott D, Davis L, Hart S, Thomas A, & Hopson S, (2019). Understanding violence and developing resilience with African American youth in high-poverty, high-crime communities. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 297–307. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C, & Richmond T, (2008). The relationship between community violence exposure and mental health symptoms in urban adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 15, 833–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennis J, Mason M, & Cao Y, (2013). Qualitative GIS and the visualization for narrative activity space data. International Journal of Geographic Information Science, 27(2): 267–291, doi: 10.1080/13658816.2012.678362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar B,Gortmaker S, Bull F, & Buka S, (2004). Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of safety predict reduced physical activity among urban children and adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion, 18(5), 378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrel-Samuels S, Bacallao M, Brown S, Bower M, & Zimmerman M, (2016). Community engagement in youth violence prevention: Crafting methods to context. Journal of Primary Prevention, 37, 189–207, DOI 10.1007/s10935-016-0428-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak D, Salzinger S, Feldman R, & Stueve C, (2004). Pathologic adaptation to community violence among inner-city youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74(2), 196–208. DOI: 10.1037/0002-9432.74.2.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell C, & Tharp R, (2012). Integrating cultural community psychology: Activity settings and the shared meanings of intersubjectivity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 22–30. DOI 10.1007/s10464-011-9434-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policing in Chicago Research Group (2018). Tracked and Targeted: Early findings on Chicago’s Gang Database. Retrieved from http://erasethedatabase.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Tracked-Targeted-0217.pdf

- Rasmussen A, Aber M, & Bhana A, (2004). Adolescent coping and neighborhood violence: Perceptions, exposure, and urban youths’ efforts to deal with danger. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(1/2), 61–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengifo A, Pater M, & Velaquez B, (2017). Crime, Cops, and Context: Risk and Risk-Management Strategies Among Black and Latino Youth in New York City. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(3), 452–471, 10.1177/0093854816682047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards M, Romera E, Zakaryan A, Carey D, Deane K, Quimby D, Patel N, & Burns M, (2014). Assessing urban African American youths’ exposure to community violence through a daily sampling method, Psychology of Violence, 5(3), 275–284, 10.1037/a0038115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AL, (2018). Intersectional ecologies: Positioning intersectionality in settings-level research. In Santos CE & Toomey RB (Eds.), Envisioning the Integration of an Intersectional Lens in Developmental Science. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 161, 57–74. DOI: 10.1002/cad.20248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P, (2006). Navigating dangerous streets: The sources and consequences of street efficacy. American Sociological Review, 71, 826–846. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J, & Patton D, (2016). Posttraumatic stress symptoms in context: Examining trauma responses to violent exposures and homicide death among black males in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(2), 212–223. 10.1037/ort0000101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer M, Fegley S, & Seaton G, (2004). Understanding hypermasculinity in context: A theory-driven analysis of urban adolescent male coping responses. Research in Human Development, 1(4), 229–257. DOI: 10.1207/s15427617rhd0104_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman A, Mcdonald C, Wiebe D, Thomas N, Guerra T, Kassam-Adams N, & Richmond T, (2010). Youth’s strategies for staying safe and coping with the stress of living in violent communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 38(7). 874–885. DOI: 10.1002/jcop.20402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]