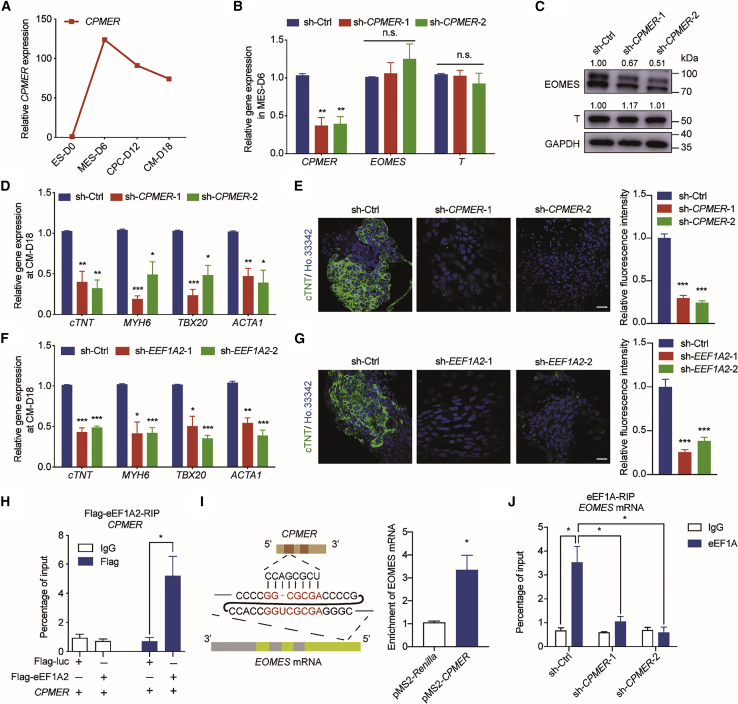

Figure 6.

CPMER/eEF1A2 conservatively functions in Eomes translation and human CM differentiation

(A) Expression pattern of CPMER during hESC-derived CM differentiation.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of expression of CPMER and mesodermal marker genes (EOMES and T) in CPMER knockdown cells. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments.

(C) Western blot analysis of EOMES and T protein levels.

(D) qRT-PCR analysis of CM marker gene expression. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments.

(E) cTnT immunostaining (green) on day 18 (left) and statistics for relative fluorescence intensity (right). Scale bar, 20 μm. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 6 fields from 3 independent experiments.

(F) qRT-PCR analysis of CM marker gene expression. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments.

(G) cTnT immunostaining (green) on day 18 (left) and statistics for relative fluorescence intensity (right). Scale bar, 20 μm. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 6 fields from 3 independent experiments.

(H) RIP analysis for the exogenous expression of CPMER and FLAG-eEF1A2 in 293T cells, determined by an anti-FLAG antibody. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments.

(I) Regions of potential recognition between CPMER and EOMES mRNA (left) and MS2bp-YFP RNA pull-down analysis for exogenous expression of pMS2-CPMER and human EOMES mRNA in 293T cells (right). Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments.

(J) Endogenous RIP analysis for the interaction of eEF1A with EOMES mRNA. Data shown are the mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 (versus sh-Ctrl); Student’s t test.

See also Figure S6.