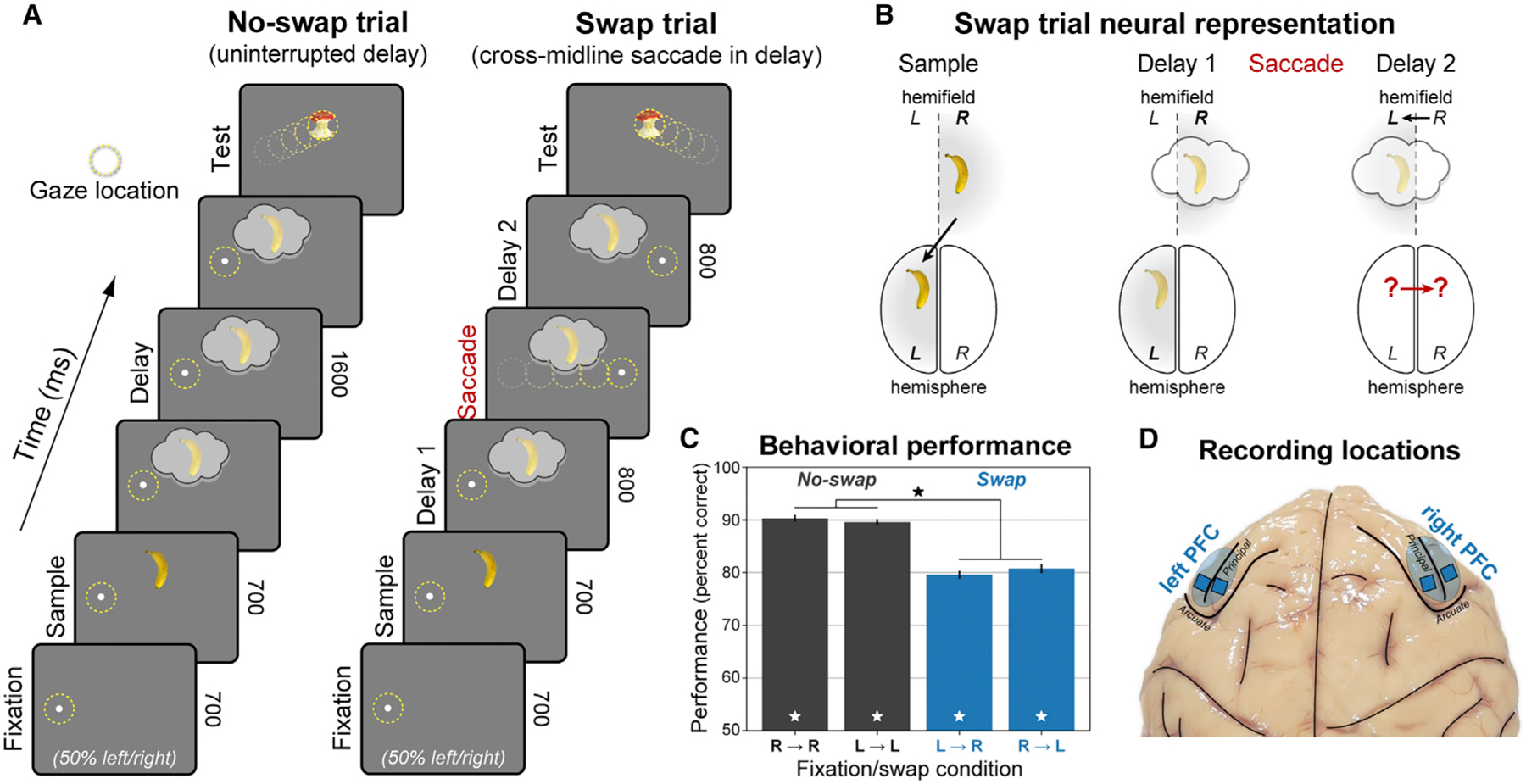

Figure 1. Behavioral and electrophysiological methods.

(A) Hemifield-swap working memory (WM) task. Subjects fixated to the left or right while a sample object was presented in the center, placing it in the right or left visual hemifield, respectively. Samples could be one of two objects, presented in one of two locations (above or below center). Both the object and its location needed to be remembered over a blank 1.6 s delay. After the delay, a series of two test objects was displayed, and subjects responded to the one that did not match the sample in object identity or upper/lower location (response to first object shown for brevity). In ‘‘no-swap’’ trials (left), the WM delay was uninterrupted. In ‘‘swap’’ trials (right), subjects were instructed to saccade to the opposite side mid-delay, switching the visual hemifield of the remembered location relative to gaze.

(B) Neural representation of WM in swap trials. The WM trace is initially encoded in the prefrontal hemisphere contralateral to the sample. We tested whether the change in gaze on swap trials caused the WM traces to transfer to the other hemisphere.

(C) Mean performance (± SEM across 56 sessions) for each swap condition and visual hemifield. Monkeys performed the task well (white stars, significant versus chance), with a small but significant decrease (black star) on swap trials.

(D) Electrophysiological signals were recorded bilaterally from 256 electrodes in lateral prefrontal cortex (PFC).