Abstract

We studied the physiological effect of the interconversion between the NAD(H) and NADP(H) coenzyme systems in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing the membrane-bound transhydrogenase from Escherichia coli. Our objective was to determine if the membrane-bound transhydrogenase could work in reoxidation of NADH to NAD+ in S. cerevisiae and thereby reduce glycerol formation during anaerobic fermentation. Membranes isolated from the recombinant strains exhibited reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH and by NADH in the presence of NADP+, which demonstrated that an active enzyme was present. Unlike the situation in E. coli, however, most of the transhydrogenase activity was not present in the yeast plasma membrane; rather, the enzyme appeared to remain localized in the membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. During anaerobic glucose fermentation we observed an increase in the formation of 2-oxoglutarate, glycerol, and acetic acid in a strain expressing a high level of transhydrogenase, which indicated that increased NADPH consumption and NADH production occurred. The intracellular concentrations of NADH, NAD+, NADPH, and NADP+ were measured in cells expressing transhydrogenase. The reduction of the NADPH pool indicated that the transhydrogenase transferred reducing equivalents from NADPH to NAD+.

Ethanol produced from Saccharomyces cerevisiae will probably become more important in the future as a source of transportation fuel. High product yield is important since the raw materials constitute a major part of the production cost (44). To make ethanol competitive as an alternative fuel, the yield must be improved by repressing the formation of biomass and by-products. Glycerol, which is formed during the fermentation of glucose to ethanol, is the most important by-product (31).

The major role of glycerol formation is to maintain the redox balance in the cytoplasm, whereby surplus NADH formed in cellular anabolic reactions is reoxidized to NAD+ (1, 25, 33). Excess NADH is generated by the assimilation of sugars to biomass and the production of various metabolic end products, including acetic acid, succinic acid, pyruvic acid, and acetaldehyde. The overall process of assimilation leads to the formation of surplus NADH (1, 42). During aerobic growth this process is balanced by oxidation of NADH in the respiratory chain of the mitochondria. In the absence of oxygen as an electron acceptor, glycerol is formed from dihydroxyacetone phosphate, and there is concomitant oxidation of 1 mol of NADH per mol of glycerol.

Whereas NADH is a reductant that is produced and consumed mainly in catabolic reactions, NADPH serves primarily as an anabolic reductant in yeasts. The NADPH-NADP+ and NADH-NAD+ systems are separated in yeasts due to the absence of enzymatically catalyzed pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenation and NAD(H) kinase activity (6, 8, 24). The lack of pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenation has considerable consequences for the redox balances of the NAD(H) and NADP(H) coenzyme systems in yeasts (42). Each coenzyme system must maintain a delicate balance between formation and consumption of reducing equivalents. Formation of NADPH occurs primarily in the pentose phosphate pathway (7).

Membrane-bound transhydrogenase is found in the inner mitochondrial membranes of animal cells and in the plasma membranes of many bacteria, where one of its functions is to provide NADPH for biosynthesis (17, 45). This enzyme catalyzes the reversible transfer of a hydride ion equivalent between NAD(H) and NADP(H) and is coupled to the proton motive force. The reaction can be summarized as:

|

1 |

where n is the number of protons pumped across the membrane and in and out indicate the matrix and the intermembrane space, respectively, of mitochondria or the cytoplasm and the periplasmic space, respectively, of bacteria. The number of protons pumped across the membrane per transferred hydride ion has been determined to be close to unity (13, 15). The enzyme of Escherichia coli is composed of two membrane-spanning subunits, the α and β subunits, arranged in an α2β2 form. The molecular masses of the α and β subunits, encoded by the pntA and pntB genes, are 50 and 47 kDa, respectively (10).

Depending on the intracellular concentrations of NADH, NAD+, NADPH, and NADP+, NADH can be consumed and NADPH can be produced by the transhydrogenase. Therefore, if transhydrogenase activity is expressed in glucose-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells, it might result in a decrease in glycerol formation and a decrease in carbon flux through the pentose phosphate pathway, where there is a loss of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide. The reduction in glycerol formation and the reduction in carbon dioxide formation could then be redirected towards formation of ethanol, which would lead to a higher ethanol yield.

A gene for a transhydrogenase from Azotobacter vinelandii has been cloned and expressed in yeast (30). The transhydrogenase from A. vinelandii belongs to a different class of enzymes. It is soluble and does not pump protons; i.e., it catalyzes a reaction (equation 1) with n = 0. Assuming a cytoplasmic location, it was found that the soluble transhydrogenase expressed in yeast produced NADH rather than consumed it. This finding was consistent with measurements of the total cellular amounts of the four nucleotides involved in anaerobically growing yeast, which showed that the ([NADPH]/[NADP+])/([NADH]/[NAD+]) ratio was 35 (30).

The situation could be different with a transhydrogenase that couples proton translocation with catalysis. Depending on which membrane the enzyme enters (plasma membrane, vacuolar membrane, or mitochondrial inner membrane) and in which orientation it enters, an electrochemical proton potential (Δp) could alter the equilibrium of the reaction (equation 1).

In this paper, we describe the expression of the E. coli pntA and pntB genes in S. cerevisiae. Our objective was to determine if the membrane-bound transhydrogenase could work in the reoxidation of NADH to NAD+ in S. cerevisiae and thereby reduce formation of glycerol in anaerobic fermentations. Although this objective was not achieved, the presence of the transhydrogenase had interesting physiological consequences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

E. coli DH5α [F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rk− mk+) supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1] (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for subcloning. The following two S. cerevisiae strains based on strain T2-3D (47) were used in this work: TN1 (MATα ho-Δ1) and TN2 (MATα ho-Δ1 ura3-Δ20::SUC2) (30). TN3, TN24, and TN25 are transformants of TN2 and contain the self-replicating plasmids YEp24-PGK-TDH, YEp24PGKαTDHβ, and pRSPGKαTDHβ, respectively.

DNA manipulation and transformation.

Plasmid manipulation, plasmid DNA isolation, agarose gel electrophoresis, and purification of DNA fragments were performed by using standard protocols (35). Restriction enzymes, DNA polymerase, and ligase were purchased from Promega (Madison, Wis.) and were used as recommended by the manufacturer. Transformation of E. coli was carried out by standard techniques (35), and transformants were grown in L-broth (35) containing 100 mg of ampicillin per ml. Yeast cells were made competent for plasmid uptake by treatment with lithium acetate and polyethylene glycol (38). Transformants were plated directly onto selective media.

Plasmids and plasmid construction.

The plasmids used for construction of an expression plasmid for the E. coli pntA and pntB genes were pSA2, containing the pnt genes from E. coli (18), the expression vector YEp24-PGK (46), pUC19-TDH, and the centromere-based vector pRS316 (40). pUC19-TDH consists of pUC19 (50) with a PCR-amplified BamHI fragment (1.27 kb) containing the promoter (0.69 kb) and transcription termination (0.58 kb) regions of the yeast TDH3 (triosephosphate dehydrogenase) gene (4) separated by a BglII site.

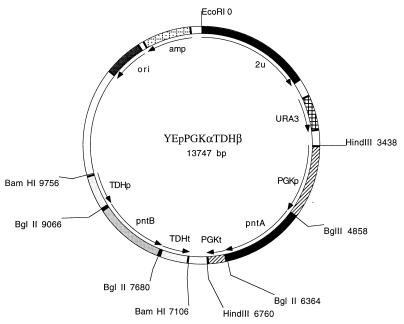

The coding regions of pntA and pntB (11) were amplified by PCR by using pSA2 as the template and the following primers provided with BglII restriction sites (underlined regions) corresponding to the upstream and downstream ends of the genes: upstream pntA primer 5′-GCGCGAGATCTTCTAGAATGCGAATTGGCATACCAAG-3′; downstream pntA primer 5′-CGCGCAGATCTTCTAGATTAATTTTTGCGGAACATTTTC-3′; upstream pntB primer 5′-GCGCGAGATCTAAAATGTCTGGAGGATTAGTTAC-3′; and downstream pntB primer 5′-CGCGCAGATCTTTACAGAGCTTTCAGGATTGC-3′. The sequences of the PCR-amplified pntA and pntB fragments were verified by DNA sequencing. The amplified pntA fragment was digested with BglII and ligated into the BglII site of YEp24-PGK, and the pntB fragment was also digested with BglII and ligated into the BglII site of pUC19-TDH. The pntB fragment containing the TDH3 promoter and terminator was excised from pUC19-TDH by using BamHI and finally was ligated into BamHI-cleaved YEp24-PGK containing the pntA gene. The resulting expression plasmid, YEpPGKαTDHβ (Fig. 1), contained the pntA gene under the control of the PGK1 promoter and the pntB gene under the control of the TDH3 promoter. The reference plasmid YEp24-PGK-TDH, which did not contain the pnt coding regions, was obtained by inserting the TDH3 1.27-kb BamHI promoter-terminator fragment into BamHI-cleaved YEp24-PGK.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the yeast YEpPGKαTDHβ high-copy-number plasmid containing the E. coli genes pntA and pntB, which encode the α and β subunits, respectively, of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Abbreviations: PGKp, PGK1 promoter, PGKt, PGK1 terminator; TDHp, TDH3 promoter, TDHt, TDH3 terminator. The directions of the promoter-gene-terminator fragments are the same in the pRSPGKαTDHβ low-copy plasmid.

In order to construct a yeast-replicating plasmid with a low copy number containing the pntA and pntB genes, we excised a fragment containing the PGK1 promoter and terminator and the pntA gene from the pntA-containing YEp24-PGK derivative by using HindIII and ligated it into HindIII-cleaved pRS316. Finally, a fragment containing the TDH3 promoter and terminator and the pntB gene was excised from the pntB-containing pUC19-TDH derivative by using BamHI and was ligated into BamHI-cleaved pRS316 containing the pntA gene, which resulted in plasmid pRSPGKαTDHβ.

Expression of pnt genes in S. cerevisiae and preparation of crude cell extract.

Strain TN2 was transformed with plasmids YEp24-PGK-TDH, YEpPGKαTDHβ, and pRSPGKαTDHβ, which resulted in reference strain TN3 and strains TN24 and TN25, respectively.

Transformants were grown in 1-liter flasks with shaking at 30°C in 200 ml of minimal medium, which contained (per liter) 1.7 g of yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and without ammonium sulfate (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), 5 g of (NH4)2SO4, and 22 g of glucose and was buffered to pH 5.8 with 10 g of succinic acid per liter and 6 g of NaOH per liter, until the mid-logarithmic phase. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 10 min at 4,400 × g and were washed in TED buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.8], 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA). The pellet was resuspended in 3 ml of TED buffer containing protease inhibitors at the concentration recommended by the manufacturer (Boehringer-Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) (complete protease inhibitor cocktail) and was vortexed twice for 5 min at 4°C with an equal volume of glass beads (diameter, 0.5 mm). The lysate was centrifuged for 5 min at 12,000 × g at 4°C, and the supernatant was stored at −70°C.

Isolation of membranes.

Crude cell extract was centrifuged for 60 min at 135,000 × g at 4°C to obtain a total membrane fraction and a soluble fraction. For the analysis of the subcellular distribution of marker enzymes, the total membranes (30 mg of protein) were suspended in 1 ml of TED buffer containing the protease inhibitor cocktail and 10% (wt/wt) sucrose and were layered onto a 20 to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose gradient in the buffer described above. After centrifugation for 14 h at 160,000 × g at 4°C, 0.3-ml fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and stored at −70°C until they were used. For purification of the yeast membranes containing E. coli transhydrogenase, the total membranes (15 to 30 mg of protein) were suspended in 1 ml of TED buffer containing the protease inhibitor cocktail (Boehringer-Mannheim) and were applied to a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of 5 ml of 28% (wt/wt) sucrose and 5 ml of 38% (wt/wt) sucrose. After centrifugation for 14 h at 160,000 × g at 4°C, membranes enriched for transhydrogenase activity were recovered at the 28% sucrose–38% sucrose interface. The band was collected, diluted in 5 volumes of TED buffer, and pelleted by centrifugation for 30 min at 135,000 × g at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of TED buffer containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol and was stored at −70°C until it was used.

Enzyme assays.

The method used to measure transhydrogenase activity was based on the method of Kaplan (21). The reaction was carried out at 25°C in a 1-ml (final volume) mixture containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1 mM KCN, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.4 mM 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), and 0.4 mM NADPH (Sigma). The reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH was measured by determining the increase in absorbance at 375 nm. An extinction coefficient of 5.1 mM−1 cm−1 was used to calculate specific activity (expressed in units per milligram of protein); 1 U was equivalent to conversion of 1 μmol of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ to 3-acetylpyridine-NADH per min. For transhydrogenation of 3-acetylpryidine-NAD+ by NADH in the presence of NADP+, 0.4 mM NADH (Sigma), and 0.4 mM NADP+ were added instead of NADPH to the buffer system described above. Plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity was assayed by using a modification of the protocol of Baginsky et al. (2) and 1 to 5 mg of membrane protein at 25°C in a 0.3-ml reaction mixture containing 50 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) adjusted to pH 6.5 with Tris, 2 mM ATP, 10 mM MgSO4, 50 mM KNO3 (to inhibit vacuolar ATPase activity), 5 mM sodium azide (to inhibit mitochondrial ATPase activity), and 0.2 mM ammonium heptamolybdate (to inhibit acid phosphatase activity). After 30 min of incubation, each reaction was stopped with 0.3 ml of ice-cold stop solution containing 0.15 M ascorbic acid, 5 mM ammonium heptamolybdate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.5 M HCl. Color developed on ice for 10 min, and the absorbance at 850 nm was determined. One unit of activity corresponded to 1 μmol of Pi/min. For the vacuolar H+-ATPase activity assay, 2 mM sodium azide and 0.1 mM sodium vanadate (to inhibit plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity) were added instead of 5 mM sodium azide and KNO3 to the buffer systems described above.

Cytochrome c oxidase activity was measured by monitoring the initial rate of decrease in absorbance at 550 nm at 25°C in a 1-ml reaction mixture containing 1 to 5 mg of sample protein, 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), and 25 μM cytochrome c (Sigma) reduced with sodium dithionite. One unit of activity corresponded to 1 μmol of cytochrome c/min. An extinction coefficient of 18.5 mM−1 cm−1 was used to calculate the specific activity.

The NADPH-cytochrome c reductase assay was performed like the cytochrome c reductase assay, except that the reduction of oxidized cytochrome c was measured by monitoring the initial rate of increase in absorbance at 550 nm in a 1-ml reaction mixture containing 1 to 5 mg of sample protein, 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), 25 μM cytochrome c, 1 mM KCN (to inhibit cytochrome oxidase activity), and 0.1 mM NADPH.

Western blot analysis.

Protein samples (10 μg) were mixed with 4 volumes of loading buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 10% (wt/vol) SDS, 5% (vol/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue. After incubation for 15 min at 30°C, the samples were loaded onto a gradient SDS-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel (4 to 20%; crosslinker, 2.6%; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). After gel electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Trans-Blot transfer medium; Bio-Rad), and a Western blot analysis was carried out by using transhydrogenase-specific polyclonal rabbit antibodies and the Bio-Rad alkaline phosphatase method (Immunoblot AP system). Marker proteins were visualized by staining the preparation with Coomassie blue R-250 (Sigma).

Protein concentration determination.

Protein concentrations were determined by using the method of Bradford (5); bovine serum albumin (Bio-Rad) was used as the standard.

Experimental setup for batch cultivation.

Anaerobic batch cultures were grown at 30°C and at a stirring speed of 800 rpm in custom-manufactured bioreactors containing mineral medium (43) supplemented with glucose and (NH4)2SO4 at concentrations of 25 and 7.5 g/liter, respectively. Vitamins were filter sterilized and added after heat sterilization of the medium. Ergosterol and Tween 80 were included in the medium at concentrations of 4.2 and 175 mg/g (dry weight), respectively. To prevent foaming, 75 μl of an antifoam agent (catalog no. A-5551; Sigma) was added. The working volume was 4.5 liters, and the pH was maintained at 5.0 by the addition of 2 M KOH. The bioreactors were equipped with off-gas condensers cooled to 2°C. The bioreactors were continuously sparged with N2 containing less than 5 ppm of O2, which was obtained by passing technical quality N2 (AGA, Copenhagen, Denmark) containing less than 100 ppm of O2 through a column (250 by 30 mm) that was filled with copper flakes and heated to 400°C. The column was regenerated daily by sparging it with H2 (AGA). A mass flow controller was used to keep the gas flow into the bioreactors constant at 0.50 liter of N2 per min, and Norprene tubing (Cole-Parmer Instruments, Vernon Hills, Ill.) was used throughout the apparatus in order to minimize the diffusion of oxygen into the bioreactors. The bioreactors were inoculated so that the initial biomass concentration was 1 mg/liter by using precultures grown in unbaffled shake flasks at 30°C and 100 rpm for 24 h. Anaerobic batch cultivation was carried out three times for each strain.

Determination of dry weight.

Dry weight was determined gravimetrically by using nitrocellulose filters (pore size, 0.45 μm; Gelman Sciences). The filters were predried in a microwave oven for 10 min. A known volume of culture liquid was filtered and washed with an equal volume of demineralized water, and this was followed by drying in a microwave oven for 15 min. The relative standard deviation (RSD) of the determinations was less than 1.5% based on three measurements.

Analysis of culture filtrate.

Cell-free samples were withdrawn directly from each bioreactor through a capillary connected to a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter and were subsequently stored at −40°C. Glucose, ethanol, glycerol, acetic acid, pyruvic acid, succinic acid, and 2-oxoglutarate contents were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (RSD, <0.6%; n = 3) by using a type HPX-87H Aminex ion exclusion column (Bio-Rad). The column was eluted at 60°C with 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. Pyruvic acid, acetic acid, and 2-oxoglutarate contents were determined with a Waters model 486 UV meter (Millipore, Milford, Mass.) at 210 nm, whereas the concentrations of other compounds were determined with a Waters model 410 refractive index detector (Millipore). The CO2 concentration in the off-gas was determined with a model 1308 acoustic gas analyzer (Brüel and Kjaer, Copenhagen, Denmark) (RSD, 0.02%) (9).

Preparation of extracts and measurement of intracellular nucleotide contents.

The intracellular nucleotides were extracted from cells growing anaerobically in batch cultures. Five milliliters of culture liquid was withdrawn from a bioreactor and sprayed into 20 ml of 60% methanol at −40°C within 1 s. Except for the following changes, the rest of the procedure was carried out as described previously for the cold methanol extraction method (12). Instead of storing the samples in a freezer after the cells were quenched in cold methanol, we extracted the nucleotides from the cells and quantified them immediately. Instead of using a neutral 2 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)] buffer for collection of the nucleotides during the extraction, we used 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.0) for extraction of NAD+ and NADP+, while 50 mM Tris-Cl (pH 9.0) was used for extraction of NADH and NADPH; this was done to increase the stability of the compounds. The concentrations of the nucleotides were determined immediately after the volumes of the samples were reduced by evaporation under a vacuum.

The contents of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH in the samples were determined enzymatically (3). The nucleotide concentrations were determined by using standard curves for each compound. The average RSD of single measurements was 8%. The results are presented below with standard deviations of the means.

RESULTS

Cloning and expression of the pnt genes in S. cerevisiae.

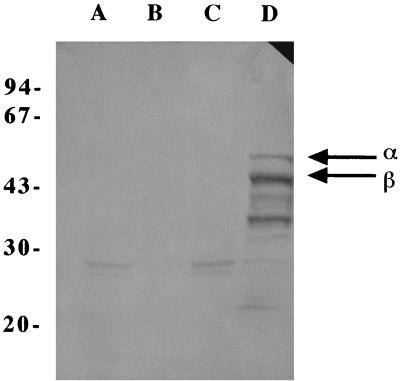

We constructed a high-copy-number expression vector based on YEp24 and a low-copy-number expression vector based on pRS316. Both expression vectors contained the promoters and terminators of the yeast phosphoglycerate kinase gene (PGK1) and the triosephosphate dehydrogenase gene (TDH3). Both promoters were strong, more or less constitutive, and suitable for high levels of expression in S. cerevisiae (23, 27). Based on the previously published E. coli pntA and pntB sequences (11), primers were designed for PCR amplification of the genes. For expression in S. cerevisiae the amplified pntA and pntB genes were subcloned into the yeast expression vectors YEp24 and pRS316. The resulting expression plasmids contained the pntA gene under the control of the PGK1 promoter and the pntB gene under the control of the TDH3 promoter, which resulted in plasmids YEpPGKαTDHβ and pRS316PGKαTDHβ. After transformation, production of recombinant transhydrogenase in S. cerevisiae with the high-copy-number construct was confirmed by a Western blot analysis (Fig. 2) in which transhydrogenase-specific polyclonal antibodies were used. Most of the transhydrogenase expressed in S. cerevisiae was present in the total membrane fraction, and almost nothing was present in the soluble fraction. The Western blot analysis also indicated that severe proteolytic degradation of both subunits of the transhydrogenase occurred, and there were two major proteolytic products, at 43 and 33 kDa (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Recombinant transhydrogenase produced by S. cerevisiae, as analyzed by Western blotting by using transhydrogenase-specific polyclonal antibodies. Lane A, soluble fraction of reference strain TN3 not expressing the pnt genes; lane B, total membrane fraction of strain TN3; lane C, soluble fraction of strain TN24 expressing the pnt genes; lane D, total membrane fraction of strain TN24. The sizes of the molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. The arrows indicate the positions of the α and β subunits.

Recombinant transhydrogenase activity.

The specific enzyme activity of the recombinant transhydrogenase expressed in S. cerevisiae was measured in cell extracts of biomass samples obtained from the exponential growth phase. The activity in strain TN25, which expressed the pnt genes from a low-copy plasmid, was 0.115 U per mg of protein, while the activity in strain TN24, which contained a high-copy-number plasmid with the pnt genes, was 1.51 U per mg of protein. No transhydrogenase activity was detected in samples of reference strains TN1 and TN3 (30).

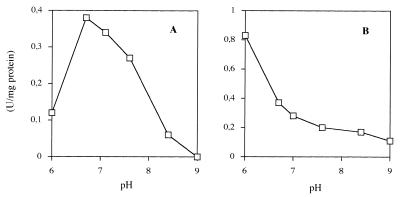

Influence of pH on the recombinant transhydrogenase activity.

To determine the activity of the recombinant transhydrogenase and to confirm the normal catalytic function of the protein, the rates of reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH and by NADH in the presence of NADP+ were investigated in strain TN24 expressing the pnt genes at a high level (Fig. 3). The pH dependence of the rate of reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH (reverse transhydrogeneration) was bell shaped with an optimum at pH 6.8 (Fig. 3A). The pH profile for the reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADH in the presence of NADP+ was quite different. This profile revealed that there was a very steep monotonic increase as the pH decreased from 7.0 to 6.0 (Fig. 3B). Both profiles were identical to the profiles obtained for E. coli cell extracts (20).

FIG. 3.

pH dependence of the rate of reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH (A) and the rate of reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADH in the presence of NADP+ (B), catalyzed by transhydrogenase produced by S. cerevisiae TN24 expressing the E. coli pnt genes.

Cellular location of the recombinant transhydrogenase.

If one would like to stimulate the forward reaction (equation 1), and if the ([NADPH]/[NADP+])/([NADH]/NAD+]) ratio is high, a recombinant transhydrogenase expressed in S. cerevisiae would have to be targeted to a membrane in which Δp is large enough and has the proper orientation. Suitable membrane systems include plasma, vacuolar, and Golgi membranes (22, 49), provided that membrane insertion of the enzyme relative to the cytoplasm is the same as it is in bacteria.

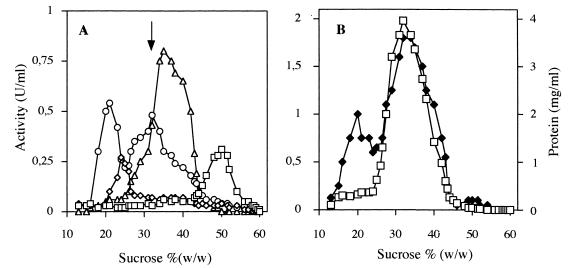

In order to determine the cellular location of the recombinant transhydrogenase in S. cerevisiae, marker enzymes typical of distinct membrane systems of the yeast cell were assayed in the fractions obtained by centrifugation through a 20 to 60% (wt/wt) sucrose gradient (Fig. 4). Plasma membranes were detected by performing a vanadate-sensitive H+-ATPase assay, vacuolar membranes were detected by measuring KNO3-sensitive H+-ATPase activity, membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) were detected by performing an NADPH-cytochrome c reductase assay, and mitochondrial membranes were detected by monitoring cytochrome c oxidase activity.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of recombinant E. coli transhydrogenase in yeast membranes fractionated in a sucrose gradient. Total membranes were isolated from yeast strain TN24 and loaded onto a linear sucrose gradient. After 14 h of centrifugation, 300-μl fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and used for enzyme assays. (A) Distribution of plasma membrane H+-ATPase (□), vacuolar H+-ATPase (◊), mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase (▵), and ER NADPH-cytochrome c oxidoreductase (○). (B) Distribution of the recombinant transhydrogenase (□) and protein concentrations (⧫). The arrow in panel A indicates the position of the recombinant transhydrogenase peak in panel B.

The distribution of marker enzymes in the S. cerevisiae strain expressing transhydrogenase at a high level, TN24, was identical to the distribution in a control strain, TN3, which contained YEp24-PGK-TDH without pnt genes (data not shown). The ER marker activity, NADPH-cytochrome c reductase activity, was the only marker activity that exhibited two peaks (21 and 32% sucrose) in the membrane distribution; these two peaks probably corresponded to light and heavy microsomes originating from smooth and rough ER, respectively (36, 51). The activity of the recombinant E. coli transhydrogenase (Fig. 4A) coincided with the rough ER peak (at 32% sucrose) (Fig. 4B), indicating that the transhydrogenase expressed in S. cerevisiae is located mainly in the rough ER.

Product formation by S. cerevisiae expressing transhydrogenase from E. coli.

Anaerobic batch cultivation of transhydrogenase-containing strains TN24 and TN25 was carried out to analyze the effect of pntA and pntB expression on the maximal specific growth rate, product formation, and the intracellular levels of the four nucleotides (NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH). The effect of the level of expression of the pnt genes on these parameters was analyzed by comparing the strain TN24 and TN25 products.

Increases in the glycerol and acetate contents were observed during cultivation of strain TN24 compared with the other strains (Table 1). 2-Oxoglutarate was formed in the strain TN24 cultures expressing the pnt genes at a high copy number. Formation of 2-oxoglutarate has been observed and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography previously, and small amounts of this compound also were found in culture broth from fermentations of TN1 and TN3 (30). Small amounts of 2-oxoglutarate were found in strain TN25 cultures, while 3.3% of the carbon source was converted into 2-oxoglutarate during cultivation of strain TN24 (Table 1). The maximal specific growth rates of strains TN24 and TN25 were 0.25 and 0.33 h−1, respectively, which indicated that the level of expression of the transhydrogenase affected the growth rate.

TABLE 1.

Product yields in anaerobic, glucose-limited cultures

| Product | Yield (C-mol/C-mol of glucose) in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain TN1 (control)a | Strain TN3 (control)a | Strain TN24 (pnt at high copy number) | Strain TN25 (pnt at low copy number) | |

| Ethanol | 0.494 ± 0.012b | 0.493 ± 0.013 | 0.455 ± 0.017 | 0.488 ± 0.015 |

| Glycerol | 0.091 ± 0.002 | 0.093 ± 0.001 | 0.118 ± 0.001 | 0.110 ± 0.003 |

| CO2 | 0.275 ± 0.020 | 0.271 ± 0.018 | 0.253 ± 0.024 | 0.270 ± 0.021 |

| Succinate | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.006 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Pyruvate | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Acetate | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| Biomass | 0.111 ± 0.002 | 0.112 ± 0.003 | 0.101 ± 0.001 | 0.111 ± 0.003 |

| 2-Oxoglutarate | 0.002 ± 0.001 | 0.007 ± 0.002 | 0.033 ± 0.002 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| Total | 0.988 | 0.991 | 0.985 | 0.997 |

Data from reference 30.

Mean ± standard deviation.

For control fermentations, as well as experimental fermentations, the products measured contained approximately 98 to 99% of the utilized carbon that was added to the fermentation preparations (Table 1). The degree of reduction of substrate and products balanced within 3 to 4%, assuming that the biomass composition was equivalent to that previously determined in similar fermentations with the related wild-type strain CBS 8066 (39). However, the degree of reduction and the amount of carbon simultaneously balanced completely if it was assumed that ethanol production had been slightly underestimated.

Intracellular nucleotide levels.

To study the effect of transhydrogenase on the intracellular concentrations of NADH, NAD+, NADPH, and NADP+, we measured the nucleotide contents in cells of the high-expression strain TN24 in the exponential growth phase (Table 2). No significant differences in the concentrations of the four nucleotides were observed when we examined samples from the early and late exponential growth phases (data not shown). The NADPH/NADP+ ratio was approximately 35 times higher than the NADH/NAD+ ratio in reference strains TN1 and TN3 (30) (Table 2). The NADPH/NADP+ ratio in the high-expression strain TN24 was reduced from 4.96 to 1.95, while the NADH/NAD+ ratio was almost the same as the ratio observed for the control strains. The concentration of NADP+ was constant. The concentration of NADP(H) in strain TN24 expressing the transhydrogenase decreased, while the concentration of NAD(H) increased. The total concentration of the four nucleotides was the same as the total concentration observed for control strains TN1 and TN3.

TABLE 2.

Intracellular concentrations of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH in cells during exponential growth in anaerobic glucose batch cultures

| Strain | Intracellular concn (μmol/g [dry wt] of biomass) of:

|

NADH/NAD+ ratio | NADPH/NADP+ ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD+ | NADP+ | NADH | NADPH | |||

| TN1a | 2.87 ± 0.09b | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 5.26 ± 0.55 |

| TN3a | 2.85 ± 0.11 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 1.19 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 4.96 ± 0.52 |

| TN24 | 3.45 ± 0.07 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.50 |

Data from reference 30.

Mean ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

S. cerevisiae was genetically engineered to synthesize a membrane-bound nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase that catalyzes the proton-coupled transfer of reducing equivalents between the NAD(H) and NADP(H) coenzyme systems. Production of the recombinant transhydrogenase was confirmed by a Western blot analysis (Fig. 2). Membranes isolated from the recombinant strains exhibited reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADPH and by NADH in the presence of NADP+, which is consistent with the normal catalytic function of the recombinant protein (Fig. 3). Purified bovine transhydrogenase also catalyzes reduction of 3-acetylpyridine-NAD+ by NADH in the presence of NADPH (14, 48), which was interpreted as involving a cyclic reduction-oxidation cycle of bound NADP(H) (14). A similar reaction has been found for the E. coli enzyme at low pH values (18, 20). This pH-dependent catalytic mechanism has been observed for all known membrane-bound transhydrogenases.

Increased formation of 2-oxoglutarate was observed in strain TN24 expressing pnt genes at a high level, compared to reference strains TN1 and TN3 (30) and strain TN25, which express only one copy of the pnt genes (Table 1). The absence of increased formation of 2-oxoglutarate in strain TN25 indicated that the compound was synthesized by strain TN24 due to the high transhydrogenase activity. When ammonium is the nitrogen source, this compound and 2-oxoglutarate are converted into glutamate by glutamate dehydrogenase during oxidation of NADPH to NADP+ (28). A high rate of conversion of NADPH and NAD+ into NADP+ and NADH in strain TN24 by the transhydrogenase decreases the intracellular pool of NADPH and is expected to result in a reduced rate for the reaction catalyzed by the NADPH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. If the rate of synthesis of 2-oxoglutarate is not affected by the change in the intracellular NADPH concentration, the reduction in consumption of 2-oxoglutarate by glutamate dehydrogenase results in its secretion. Hence, secretion of 2-oxoglutarate from strain TN24 indicated that NADPH was consumed at a high rate by a transhydrogenase in this strain. The low level of expression of transhydrogenase in strain TN25 did not result in high enough consumption of NADPH to result in secretion of appreciable amounts of 2-oxoglutarate.

Introduction of the high-copy-number plasmid YEpPGKαTDHβ into strain TN3 resulted in a decrease in the maximal specific growth rate, which indicated that the level of expression of transhydrogenase affects the growth rate. Since the rate of conversion of 2-oxoglutarate to glutamate was reduced in strain TN24, the reduced maximal specific growth rate could have been due to the decrease in glutamate synthesis necessary for biomass synthesis.

There was an increase in the glycerol yield, from 0.093 C-mol/C-mol of glucose in strains TN1 and TN3 (30) to 0.110 C-mol/C-mol of glucose in the low-expression strain TN25 and 0.118 C-mol/C-mol of glucose in the high-expression strain TN24 (Table 1) (C-mol means n;umber of gram atoms of carbon in the aoumt of compound in question). Glycerol is formed during anaerobic growth of wild-type S. cerevisiae, so that excess NADH formed during the synthesis of biomass and organic acids can be redoxidized. In strains TN25 and TN24 the reaction catalyzed by transhydrogenase represents a new pathway for NADH formation since the enzyme catalyzed the reaction in the direction from consumption of NADPH and NAD+ towards formation of NADP+ and NADH. In strains TN24 and TN25 this resulted in the observed increase in the glycerol yield. The reduced biomass yield of strain TN24 reduced the net formation of NADH, but the effect on the glycerol yield was not quantified.

The acetate yield in strain TN24 was greater than the acetate yield in strains TN1 and TN3 (30). In the last two steps of acetate synthesis, pyruvate is converted into acetaldehyde and then into acetate by pyruvate decarboxylase and the NADP+-dependent cytoplasmic aldehyde dehydrogenase, respectively, so that 1 mol of NADPH is synthesized per mol of acetate formed. The greater acetate formation in strain TN24 may reflect a regulatory mechanism that compensates for the consumption of NADPH by the transhydrogenase. A similar effect has been observed in recombinant S. cerevisiae strains that express XYL1, which encodes an NADPH-consuming xylose reductase (26).

In the strain with a high level of expression of the pnt genes, the NADPH/NADP+ ratio decreased from 5.0 to 2.0, which supported the hypothesis that the transhydrogenase converted NADPH into NADH in strain TN24 (Table 2). The values also indicated that the presence of transhydrogenase did not result in equilibrium. The increased consumption of NADPH did not lead to an increased level of NADP+, so [NADPH] plus [NADP+] decreased by a factor of two in strain TN24. This change indicates that there was strict regulation of the NADP+ concentration in the cell. Furthermore, the concentration of NAD+ increased in the strain expressing the transhydrogenase, despite increased formation of NADH. This change may have been due to very rigid regulation of the NADH/NAD+ ratio, as indicated by the constant value for this ratio in the strains.

Expression of a transhydrogenase influenced the rates of formation of glycerol and acetate and the rate of consumption of 2-oxoglutarate. These reactions occurred in the cytoplasm. Thus, the changes in the flux of glycerol and acetate and in the rate of consumption of 2-oxoglutarate must have been due to changes in the rates of production of the nucleotides in the cytoplasm. This suggests that nucleotide binding sites of the membrane-bound transhydrogenase are located in this compartment.

The transhydrogenase expressed in S. cerevisiae converted NADPH and NAD+ into NADP+ and NADH, indicating that the reverse (leftward) reaction of equation 1 occurred. This reaction direction suggests that the Δp across the ER, where most of the transhydrogenase is located in S. cerevisiae, is insufficient to drive the transhydrogenase forward reaction (equation 1). There is no method to directly measure the ER lumenal pH. The results of indirect measurements and predictions of the ER microenvironment based on characteristics of several ER proteins, however, suggest that the ER pH is approximately 7 (22, 41). To our knowledge, the membrane potential across the ER membrane has not been determined, which precludes an estimate of Δp.

We do not know why the recombinant transhydrogenase tends to accumulate in rough ER and is not delivered to the plasma or vacuolar membranes. Misfolded or unassembled proteins tend to accumulate in the ER and to degrade rapidly (16, 19, 37), but our work indicates that the recombinant protein has an intact catalytic function. A certain sequence necessary for proper assembly for exit from rough ER could be missing in the sequence of E. coli transhydrogenase (32). Protein movement from the thin phospholipid-rich ER Golgi membranes to the thick sterol- and sphingolipid-rich plasma membranes could be limited by the length of the transmembrane domains (29, 34). It is possible that by adding sorting signals present in integral membrane proteins from yeast and by using screens to identify genes encoding proteins that facilitate the sorting events the membrane-bound transhydrogenase could be directed to the plasma membrane or to the vacuolar membrane. Particularly in the plasma membrane, the Δp may be sufficient to drive equation 1 in the desired direction. Assuming that the measured nucleotide levels are representative of the cytoplasm and that n in equation 1 is 1, the required proton gradient would be on the order of 100 mV. Also, the kinetics would be favored by a large proton gradient.

We found that a functional membrane transhydrogenase can be synthesized in S. cerevisiae. However, this protein is not delivered to the plasma membrane but seems to accumulate in internal membrane systems, mainly in the rough ER (Fig. 4). Our results show that product formation by S. cerevisiae expressing a transhydrogenase from E. coli is affected. We found that the yields of glycerol and acetic acid increased and the yield of ethanol decreased, indicating that a reversed reaction (equation 1) catalyzed by the transhydrogenase occurred. The intracellular concentrations of the four nucleotides confirmed that the degree of reduction of the NADP(H) pool is higher than the degree of reduction of the NAD(H) pool in S. cerevisiae expressing the transhydrogenase and that the Δp at the location of the recombinant transhydrogenase probably is insufficient to make a forward reaction (equation 1) possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the Nordic Energy Research Programme.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albers E, Larsson C, Lidén G, Niklasson C, Gustafsson L. Influence of the nitrogen source on Saccharomyces cerevisiae anaerobic growth and product formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3187–3195. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3187-3195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baginsky E S, Foa P P, Zak B. Determination of phosphate: study of labile organic phosphate interference. Clin Chim Acta. 1967;15:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergmeyer H U. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd ed. VII. Weinheim, Germany: VCH Verlagsgesellschaft Gmbh; 1985. Nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotides and dinucleotide phosphates (NAD, NADP, NADH, NADPH) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitter G A, Chang K K H, Egan K M. A multi-component upstream activation sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene promoter. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;231:22–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00293817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruinenberg P M, van Dijken J P, Scheffers W A. An enzymic analysis of NADPH production and consumption in Candida utilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:965–971. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruinenberg P M, van Dijken J P, Scheffers W A. A theoretical analysis of NADPH production and consumption in yeast. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:953–964. doi: 10.1099/00221287-129-4-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruinenberg P M, Jonker R, van Dijken J P, Scheffers W A. Utilization of formate as an additional energy source by glucose-limited chemostat cultures of Candida utilis CBS 621 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae CBS 8066: evidence for absence of transhydrogenase activity in yeasts. Arch Microbiol. 1985;142:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen L H, Schulze U, Nielsen J, Villadsen J. Acoustic off-gas analyzer for bioreactors: precision, accuracy and dynamics of detection. Chem Eng Sci. 1995;50:2601–2610. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke D M, Bragg P D. Cloning and expression of the transhydrogenase gene of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:367–373. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.367-373.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarke D M, Loo T W, Gillam S, Bragg P D. Nucleotide sequence of the pntA and pntB genes encoding the pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1986;158:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Koning W, van Dam K. A method for the determination of changes of glycolytic metabolites in yeast on a subsecond time scale using extraction at neutral pH. Anal Biochem. 1992;204:118–123. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Earle S R, Fisher R R. A direct demonstration of proton translocation coupled to transhydrogenation in reconstituted vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:827–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enander K, Rydström J. Energy-linked nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase: kinetics and regulation of purified and reconstituted transhydrogenase from beef heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14760–14766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eytan G D, Persson B, Ekebacke A, Rydström J. Energy-linked nicotinamide-nucleotide transhydrogenase: characterisation of reconstituted ATP-driven transhydrogenase from beef heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5008–5014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Nagy M, Ryter A. A deletion that includes the segment coding for the signal peptidase cleavage site delays release of Saccharomyces cerevisiae acid phosphatase from the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:723–729. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.2.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoek J B, Rydström J. Physiological roles of nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase. Biochem J. 1988;254:1–10. doi: 10.1042/bj2540001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu X, Zhang J-W, Persson A, Rydström J. Characterization of the interaction of NADH with proton pumping E. coli transhydrogenase reconstituted in the absence and in the presence of bacteriorhodopsin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1229:64–72. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)00187-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurtley S M, Helenius A. Protein oligomerization in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:277–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutton M, Day J M, Bizouarn T, Jackson J B. Kinetic resolution of the reaction catalysed by proton-translocating transhydrogenase from Escherichia coli as revealed by experiments with analogues of the nucleotide substrates. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:1041–1051. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan N O. Beef heart TPNH-DPN pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenases. Methods Enzymol. 1967;10:317–322. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klionsky D J, Nelson H, Nelson N. Compartment acidification is required for efficient sorting of proteins to the vacuole in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3416–3422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuroda S, Otaka S, Fujisawa Y. Fermentable and nonfermentable carbon sources sustain constitutive levels of expression of yeast triosephosphate dehydrogenase 3 gene from distinct promoter elements. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6153–6162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lagunas R, Gancedo J M. Reduced pyridine nucleotide balance in glucose growing Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1973;37:90–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1973.tb02961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lidén G, Walfridsson M, Ansell R, Anderlund M, Adler L, Hahn-Hägerdal B. A glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-deficient mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing the heterologous XYL1 gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3894–3896. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3894-3896.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meinander N, Zacchi G, Hahn-Hägerdal B. A heterologous reductase affects the redox balance of recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiology. 1996;142:165–172. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellor J, Dobson M J, Roberts N A, Tuite M F, Emtage J S, White S, Lowe P A, Patel T, Kingsman A J, Kingsman S M. Efficient synthesis of enzymatically active calf chymosin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1983;24:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(83)90126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moye W S, Amuro N, Rao J K M, Zalkin H. Nucleotide sequence of yeast GDH1 encoding nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8502–8508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munro S. An investigation of the role of transmembrane domains in Golgi protein retention. EMBO J. 1995;14:4695–4704. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00151.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nissen, T. L., M. Anderlund, J. Nielsen, J. Villadsen, and M. C. Kielland-Brandt. Expression of a cytoplasmic transhydrogenase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae results in formation of 2-oxoglutarate due to depletion of the NADPH pool. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Nordström K. Yeast growth and glycerol formation, carbon and redox balances. J Inst Brew. 1968;74:429–432. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nothwehr S F, Stevens T H. Sorting of membrane proteins in the yeast secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10185–10188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oura E. Reaction products of yeast fermentations. Proc Biochem. 1977;12(3):19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rayner J C, Pelham H R B. Transmembrane domain-dependent sorting of proteins to the ER and plasma membrane in yeast. EMBO J. 1997;16:1832–1841. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanderson C M, Crowe J S, Meyer D I. Protein retention in yeast rough endoplasmic reticulum: expression and assembly of human ribophorin I. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2861–2870. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schauer I, Emr S, Gross C, Schekman R. Invertase signal and mature sequence substitutions that delay intercompartmental transport of active enzyme. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1664–1675. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schiestl R H, Gietz D. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulze U. Anaerobic physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ph.D. thesis. Lyngby, Denmark: Department of Biotechnology, Technical University of Denmark; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian H, Klämbt D, Jones A M. Auxin-binding protein 1 does not bind auxin within the endoplasmic reticulum despite this being the predominant subcellular location for this hormone receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26962–26969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Dijken J P, Scheffers W A. Redox balances in the metabolism of sugars by yeast. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;32:199–224. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verduyn C, Postma E, Scheffers W A, van Dijken J P. Physiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in anaerobic glucose-limited chemostat cultures. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:395–403. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Sivers M, Zacchi G. A techno-economical comparison of the three processes for the production of ethanol from pine. Biores Technol. 1995;51:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voordouw G, van der Vies S M, Themmen A P N. Why are two different types of pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase found in living organisms? Eur J Biochem. 1983;131:527–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walfridsson M, Anderlund M, Bao X, Hahn-Hägerdal B. Expression of different levels of enzymes from the Pichia stipitis XYL1 and XYL2 genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its effect on product formation during xylose utilisation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:218–224. doi: 10.1007/s002530051041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wenzel T J, van den Berg M A, Visser W, van den Berg J A, Steensma H Y. Characterization of mutants lacking the EIa subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1992;209:697–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu L N Y, Earle S R, Fisher R R. Bovine heart mitochondrial transhydrogenase catalyzes an exchange reaction between NADH and NAD+ J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7401–7408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamashiro C T, Kane P M, Wolczyk D F, Preston R A, Stevens T H. Role of vacuolar acidification in protein sorting and zymogen activation: a genetic analysis of the yeast vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3737–3749. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zinser E, Sperka-Gottlieb C D M, Fasch E-V, Kohlwein S D, Paltauf F, Daum G. Phospholipid synthesis and lipid composition of subcellular membranes in the unicellular eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2026–2034. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2026-2034.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]