Abstract

During a survey of hypoxylaceous fungi in Medog county (Tibet Autonomous Region, China), three new species, including Hypoxylon damuense, Hypoxylon medogense, and Hypoxylon zangii, were described and illustrated based on morphological and multi-gene phylogenetic analyses. Hypoxylon damuense is characterized by its yellow-brown stromatal granules, light-brown to brown ascospores, and frequently indehiscent perispore. Hypoxylon medogense is morphologically and phylogenetically related to H. erythrostroma but differs in having larger ascospores with straight spore-length germ slit and conspicuously coil-like perispore ornamentation. Hypoxylon zangii shows morphological similarities to H. texense but differs in having Amber (47), Fulvous (43) and Sienna (8) KOH-extractable pigments and larger ascospores with straight spore-length germ slit. The multi-gene phylogenetic analyses inferred from the datasets of ITS-RPB2-LSU-TUB2 supported the three new taxa as separate lineages within Hypoxylon. A key to all known Hypoxylon species from China and related species worldwide is provided.

Keywords: Ascomycota, Hypoxylon, multigene phylogeny, taxonomy, wood-decomposing fungi, Xylariales

1. Introduction

Polyphasic taxonomic studies based on phylogenetic, chemotaxonomic, and morphological data were extensively applied to identify species and reflect evolutionary relationships of hypoxylaceous fungi in recent years [1,2,3]. Since resurrected and emended by Wendt et al. [2], 15 genera were rearranged and recognized to Hypoxylaceae by having stromatal pigments and a nodulisporium-like anamorph. According to the arrangement of the families in Sordariomycetes by Hyde et al. [4], 19 genera were accepted in Hypoxylaceae as saprobes and endophytes. Interesting, Hypoxylon species in endophytic stages may play an important ecological role in protecting their host plants from pathogens [4], and some species are related to insect vectors [2,5,6,7]. As the main family of Xylariales, Hypoxylaceae exhibits high diversity in tropical and subtropical areas [8,9,10,11]. In the classification system of Ju and Rogers [12], the genus Hypoxylon Bull. contains two subclades, the Annulata and Hypoxylon sections. Then they were segregated and the Annulata section was accepted as a new genus, Annulohypoxylon, based on molecular phylogenetic data inferred from ACT and TUB2 sequences [13]. Hypoxylon species are mainly saprobic on dead and decaying wood of angiospermous plants [14]. In this genus, more than 200 species with 1189 epithets included in the Index Fungorum have been reported so far [4,15,16]. Despite species of Hypoxylon being widely distributed throughout Asia, only 57 species were reported in China currently [17,18,19,20,21].

Medog county, Tibet Autonomous Region is located in southwest China, at the eastern end of the Himalayas and the lower reaches of the Yarlung Zangbo River, and belongs to a subtropical humid climate zone in the Himalayas, with abundant rainfall and an average annual temperature of 18.0 °C [22]. These unique climatic conditions contribute to the abundant resources of macro-fungi. In the current study, we surveyed hypoxylaceous taxa in Medog county, and three undescribed species of Hypoxylon were identified. The morphological characteristics of the three new species were described, and their nucleotide sequences were analyzed phylogenetically to confirm their status within Hypoxylon.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Specimens

The studied specimens were collected from Medog county (Tibet Autonomous Region), which is located in southwestern China. The explored sites are approximately at elevations from 800 to 1600 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.). The collected samples were dried with a portable drier (manufactured in Germany). Dried samples were labeled and then stored by ultrafreezing at −80 °C for a week to kill insects and their eggs before they were ready for studies. The Fungarium of the Institute of Tropical Bioscience and Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (FCATAS) is responsible for the preservation of specimens.

2.2. Morphological Observations

Sexual structures of the collected specimens were used for morphological observations and identification. The stroma and perithecia were observed, photographed and measured with a VHX-600E 3D microscope from the Keyence Corporation (Osaka, Japan). Fresh material was respectively immersed in water, 10% KOH, and Melzer’s reagent to observe micromorphological structures as determined by Ma et al. and Song et al. [20,21]. The observations, micrographs, and measurements of asci and ascospores were performed by using an Olympus IX73 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and the CellSens Dimensions Software (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The observations and photographs of ornamentation of ascospores were examined by scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Phenom Corporation, Netherlands) as given in Friebes and Wendelin [23]. The stromatal color and KOH-extractable pigments were assigned following the mycological color chart of Rayner [24]. The present paper contains the following abbreviations: KOH = 10% potassium hydroxide; n = number of measuring objects; M = arithmetical average of sizes of all measuring objects.

2.3. DNA Extraction, Amplification, and Sequencing

Fresh tissue of stroma was used for DNA extraction and sequence generation following the suggestions by Ma et al. and Song et al. [20,21]. Sequences of four DNA loci—ITS (internal transcribed spacer regions), nrLSU (nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA), RPB2 (RNA polymerase II second largest subunit), and β-tubulin (beta-tubulin) were selected for multi-gene phylogenetic analyses [2,25]. The target sequences were amplified by the primers ITS4/ITS5, LR0R/LR5, fRPB2-7CR/fRPB2-5F, and T1/T22 [26,27,28,29,30]. In total, six ITS, six LSU, six RPB2, and six β-tubulin sequences of new Hypoxylon specimens collected from Medog were obtained and submitted to GenBank.

2.4. Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses

The listed Hypoxylaceae and Xylariaceae species in Table 1 originated from previously published studies. Besides Hypoxylon spp., the backbone tree contained species of related genera including Annulohypoxylon, Daldinia, Hypomontagnella, Jackrogersella, Pyrenopolyporus, Rhopalostroma, and Thamnomyces with Xylaria hypoxylon (L.) Grev. and Biscogniauxia nummularia (Bull.) Kuntze chosen to be outgroups.

Table 1.

GenBank accession numbers of sequences used in the multi-gene phylogenetic analyses. T and ET represent holotype and epitype specimens, respectively. Species in bold were derived from this study. N/A: not available.

| Species Name | Specimen No. | Locality | GenBank Accession No. | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | RPB2 | β-Tubulin | Status | ||||

| Annulohypoxylon annulatum | CBS 140775 | USA | KU604559 | KY610418 | KY624263 | KX376353 | ET | [2,11,25] |

| A. moriforme | CBS 123579 | Martinique | KX376321 | KY610425 | KY624289 | KX271261 | [25] | |

| A. truncatum | CBS 140778 | USA | KX376329 | KY610419 | KY624277 | KX376352 | ET | [2,25] |

| Daldinia dennisii | CBS 114741 | Australia | JX658477 | KY610435 | KY624244 | KC977262 | T | [2,9,34] |

| D. petriniae | MUCL 49214 | Austria | JX658512 | KY610439 | KY624248 | KC977261 | ET | [2,9,34] |

| Hypomontagnella barbarensis | STMA 14081 | Argentina | MK131720 | MK131718 | MK135891 | MK135893 | T | [35] |

| Hypom. monticulosa | MUCL 54604 | French Guiana | KY610404 | KY610487 | KY624305 | KX271273 | ET | [2] |

| Hypom. submonticulosa | CBS 115280 | France | KC968923 | KY610457 | KY624226 | KC977267 | [2,9] | |

| Hypoxylon addis | MUCL 52797 | Ethiopia | KC968931 | N/A | N/A | KC977287 | T | [9] |

| H. anthochroum | YMJ 9 | Mexico | JN660819 | N/A | N/A | AY951703 | [13] | |

| H. aveirense | CMG 29 | Portugal | MN053021 | N/A | N/A | MN066636 | T | [36] |

| H. baihualingense | FCATAS 477 | China | MG490190 | N/A | N/A | MH790276 | T | [18] |

| H. baruense | UCH 9545 | Panama | MN056428 | N/A | N/A | MK908142 | [32] | |

| H. begae | YMJ 215 | USA | JN660820 | N/A | N/A | AY951704 | [13] | |

| H. bellicolor | UCH 9543 | Panama | MN056425 | N/A | N/A | MK908139 | [32] | |

| H. brevisporum | YMJ 36 | Puerto Rico | JN660821 | N/A | N/A | AY951705 | [13] | |

| H. carneum | MUCL 54177 | France | KY610400 | KY610480 | KY624297 | KX271270 | [2] | |

| H. cercidicola | CBS 119009 | France | KC968908 | KY610444 | KY624254 | KX271270 | [2,9] | |

| H . chrysalidosporum | FCATAS 2710 | China | OL467294 | OL615106 | OL584222 | OL584229 | T | [20] |

| H. crocopeplum | CBS 119004 | France | KC968907 | KY610445 | KY624255 | KC977268 | [2] | |

| H . cyclobalanopsidis | FCATAS 2714 | China | OL467298 | OL615108 | OL584225 | OL584232 | T | [20] |

| H. damuense | FCATAS 4207 | China | ON075427 | ON075433 | ON093251 | ON093245 | T | This study |

| H. damuense | FCATAS 4321 | China | ON075428 | ON075434 | ON093252 | ON093246 | This study | |

| H. dieckmannii | YMJ 89041203 | China | JN979413 | N/A | N/A | AY951713 | [13] | |

| H. duranii | YMJ 85 | China | JN979414 | N/A | N/A | AY951714 | [13] | |

| H. erythrostroma | YMJ 90080602 | China | JN979416 | N/A | N/A | AY951716 | [13] | |

| H. eurasiaticum | MUCL 57720 | Iran | MW367851 | N/A | MW373852 | MW373861 | [37] | |

| H. fendleri | DSM 107927 | USA | MK287533 | MK287545 | MK287558 | MK287571 | [38] | |

| H. ferrugineum | CBS 141259 | Austria | KX090079 | N/A | N/A | KX090080 | [23] | |

| H. fragiforme | MUCL 51264 | Germany | KM186294 | KM186295 | KM186296 | KM186293 | ET | [38] |

| H. fraxinophilum | MUCL 54176 | France | KC968938 | N/A | N/A | KC977301 | ET | [9] |

| H. fulvosulphureum | MFLUCC 13-0589 | Thailand | KP401576 | N/A | N/A | KP401584 | T | [39] |

| H. fuscum | CBS 113049 | France | KY610401 | KY610482 | KY624299 | KX271271 | ET | [2] |

| H. griseobrunneum | CBS 331.73 | India | KY610402 | MH872399 | KY624300 | KC977303 | T | [2,9,40] |

| H. guilanense | MUCL 57726 | Iran | MT214997 | MT214992 | MT212235 | MT212239 | T | [15] |

| H. haematostroma | MUCL 53301 | Martinique | KC968911 | KY610484 | KY624301 | KC977291 | ET | [35] |

| H. hinnuleum | MUCL 3621 | USA | MK287537 | MK287549 | MK287562 | MK287575 | T | [38] |

| H. howeanum | MUCL 47599 | Germany | AM749928 | KY610448 | KY624258 | KC977277 | [2,9,41] | |

| H. hypomiltum | MUCL 51845 | Guadeloupe | KY610403 | KY610449 | KY624302 | KX271249 | [2] | |

| H. invadens | MUCL 51475 | France | MT809133 | MT809132 | MT813037 | MT813038 | T | [42] |

| H. investiens | CBS 118183 | Malaysia | KC968925 | KY610450 | KY624259 | KC977270 | [2,9] | |

| H. isabellinum | STMA 10247 | Martinique | KC968935 | N/A | N/A | KC977295 | T | [9] |

| H. jecorinum | YMJ 39 | Mexico | JN979429 | N/A | N/A | AY951731 | [13] | |

| H. jianfengense | FACATAS845 | China | MW984546 | MZ029707 | MZ047260 | MZ047264 | T | [21] |

| H. larissae | FACATAS844 | China | MW984548 | MZ029706 | MZ047258 | MZ047262 | T | [21] |

| H. lateripigmentum | MUCL 53304 | Martinique | KC968933 | KY610486 | KY624304 | KC977290 | T | [2,9] |

| H. lenormandii | CBS 135869 | Cameroon | KY610390 | KY610453 | KY624262 | KM610295 | [2,43] | |

| H. liviae | CBS 115282 | Norway | NR155154 | N/A | N/A | KC977265 | ET | [9] |

| H. lividicolor | YMJ 70 | China | JN979432 | N/A | N/A | AY951734 | [13] | |

| H. lividipigmentum | YMJ 233 | Mexico | JN979433 | N/A | N/A | AY951735 | [13] | |

| H. macrosporum | YMJ 47 | Canada | JN979434 | N/A | N/A | AY951736 | [13] | |

| H. medogense | FCATAS 4061 | China | ON075425 | ON075431 | ON093249 | ON093243 | T | This study |

| H. medogense | FCATAS 4320 | China | ON075426 | ON075432 | ON093250 | ON093244 | This study | |

| H. musceum | MUCL 53765 | Guadeloupe | KC968926 | KY610488 | KY624306 | KC977280 | [2,9] | |

| H. notatum | YMJ 250 | USA | JQ009305 | N/A | N/A | AY951739 | [13] | |

| H. olivaceopigmentum | DSM 10792 | USA | MK287530 | MK287542 | MK287555 | MK287568 | T | [38] |

| H. papillatum | ATCC 58729 | USA | NR155153 | KY610454 | KY624223 | KC977258 | T | [2,9] |

| H. perforatum | CBS 115281 | France | KY610391 | KY610455 | KY624224 | KX271250 | [2] | |

| H. petriniae | CBS 114746 | France | NR155185 | KY610491 | KY624279 | KX271274 | T | [2] |

| H. pilgerianum | STMA 13455 | Martinique | KY610412 | N/A | KY624308 | KY624315 | [2] | |

| H. porphyreum | CBS 119022 | France | KC968921 | KY610456 | KY624225 | KC977264 | [2,9] | |

| H. pseudofendleri | MFLUCC 11-0639 | Thailand | KU940156 | KU863144 | N/A | N/A | [44] | |

| H. pseudofuscum | 18264 | Germany | MW367857 | MW367848 | MW373858 | MW373867 | T | [37] |

| H. pulicicidum | CBS 122622 | Martinique | JX183075 | KY610492 | KY624280 | JX183072 | T | [2,45] |

| H. rickii | MUCL 53309 | Martinique | KC968932 | KY610416 | KY624281 | KC977288 | ET | [2] |

| H. rubiginosum | MUCL 52887 | Germany | KC477232 | KY610469 | KY624266 | KY624311 | ET | [2,46] |

| H. rutilum | YMJ 181 | France | N/A | N/A | N/A | AY951752 | [13] | |

| H. samuelsii | MUCL 51843 | Guadeloupe | KC968916 | KY610466 | KY624269 | KC977286 | ET | [2,9] |

| H. shearii | YMJ 29 | Mexico | EF026142 | N/A | N/A | AY951753 | [13] | |

| H. spegazzinianum | STMA 14082 | Argentina | KU604573 | N/A | N/A | KU604582 | T | [11] |

| H. sporistriatatunicum | UCH 9542 | Panama | MN056426 | N/A | N/A | MK908140 | T | [32] |

| H. subgilvum | YMJ 88113007 | China | JQ009315 | N/A | N/A | AY951755 | [13] | |

| H. sublenormandii | JF 13026 | Sri Lanka | KM610291 | N/A | N/A | KM610303 | T | [43] |

| H. texense | DSM 107933 | USA | MK287536 | MK287548 | MK287561 | MK287574 | T | [38] |

| H. ticinense | CBS 115271 | France | JQ009317 | KY610471 | KY624272 | AY951757 | [2,13] | |

| H. trugodes | MUCL 54794 | Sri Lanka | KF234422 | NG066380 | KY624282 | KF300548 | ET | [2,9] |

| H. ulmophilum | YMJ 350 | Russia | JQ009320 | N/A | N/A | AY951760 | [13] | |

| H. vogesiacum | CBS 115273 | France | KC968920 | KY610417 | KY624283 | KX271275 | [2] | |

| H. wujiangense | GMBC0213 | China | MT568854 | MT568853 | MT585802 | MT572481 | T | [19] |

| H. wuzhishanense | FCATAS2708 | China | OL467292 | OL615104 | OL584220 | OL584227 | T | [20] |

| H. zangii | FCATAS 4029 | China | ON075423 | ON075429 | ON093247 | ON093241 | T | This study |

| H. zangii | FCATAS 4319 | China | ON075424 | ON075430 | ON093248 | ON093242 | This study | |

| Jackrogersella cohaerens | CBS 119126 | Germany | KY610396 | KY610497 | KY624270 | KY624314 | [2] | |

| J. multiformis | CBS 119016 | Germany | KC477234 | KY610473 | KY624290 | KX271262 | ET | [2,9] |

| Pyrenopolyporus hunteri | MUCL 52673 | Ivory Coast | KY610421 | KY610472 | KY624309 | KU159530 | ET | [2,25] |

| P. laminosus | MUCL 53305 | Martinique | KC968934 | KY610485 | KY624303 | KC977292 | T | [2,9] |

| P. nicaraguensis | CBS 117739 | Burkina Faso | AM749922 | KY610489 | KY624307 | KC977272 | [2,9,41] | |

| Rhopalostroma angolense | CBS 126414 | Ivory Coas | KY610420 | KY610459 | KY624228 | KX271277 | [2] | |

| Thamnomyces dendroidea | CBS 123578 | French Guiana | FN428831 | KY610467 | KY624232 | KY624313 | T | [2,47] |

| Xylaria hypoxylon | CBS 122620 | Sweden | KY610407 | KY610495 | KY624231 | KX271279 | ET | [2] |

| Biscogniauxia nummularia | MUCL 51395 | France | KY610382 | KY610427 | KY624236 | KX271241 | [2] | |

The alignment, trimming, and concatenation of sequences followed Song et al. [21]. The multi-gene phylogenetic analyses were performed by using two methods of maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian analyses (BA) based on ITS-LSU-RPB2-β-tubulin datasets and ITS-β-tubulin datasets. The latter was used for an added validation to the former. Maximum likelihood analyses used raxmlGUI 2.0 with 1000 bootstrap replicates and GTRGAMMA+G as a substitution model [20,31,32]. Bayesian analyses used MrBayes 3.2.6 with jModelTest 2 conducting model discrimination and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. Every 100th generation was sampled as a tree with 1,000,000 generations running for six MCMC chains [20,33]. Phylogenetic trees were viewed and edited by FigTree version 1.4.3 and Photoshop CS6.

This study selected 89 taxa from 10 genera to perform phylogenetic analysis, including 3 Annulohypoxylon spp., 2 Daldinia spp., 3 Hypomontagnella spp., 72 Hypoxylon spp., 2 Jackrogersella spp., 3 Pyrenopolyporus spp., 1 Rhopalostroma sp., and 1 Thamnomyces sp. with X. hypoxylon and B. nummularia added as the outgroups. The sequence datasets comprised 306 sequences with 91 ITS, 62 LSU, 62 RPB2, and 91 β-tubulin sequences. After being aligned and trimmed, the combined dataset contained 3530 characters including gaps with 587 characters for ITS, 867 characters for LSU, 729 characters for RPB2, and 1347 characters for β-tubulin alignment, of which 1537 characters were parsimony-informative.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis

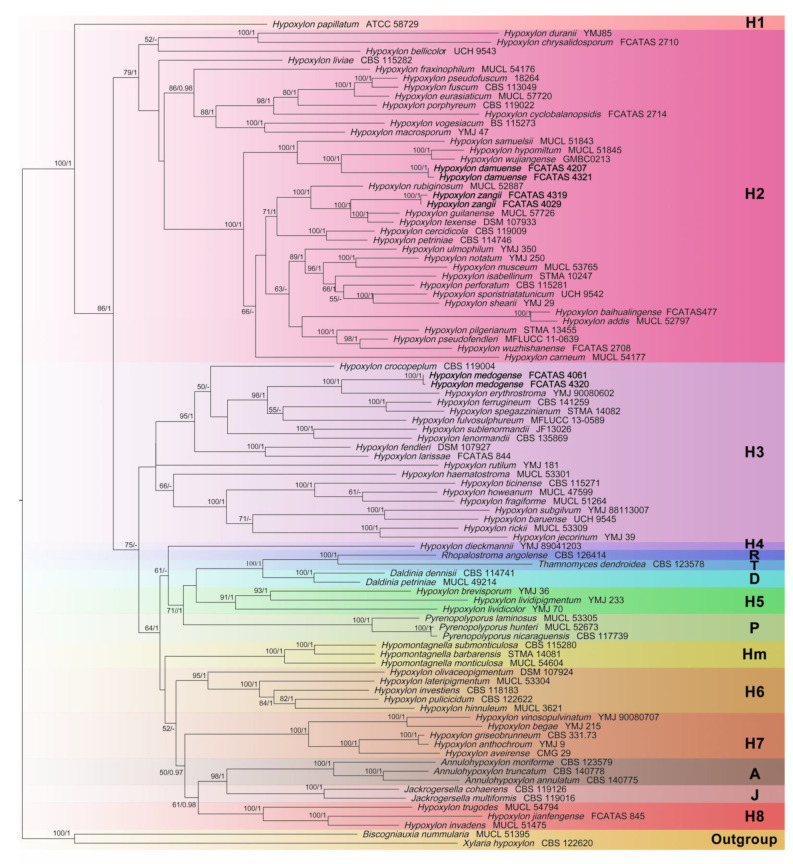

The best-scoring ML tree was built with a final ML optimization likelihood value of −77,579.198447. Bayesian posterior probabilities were calculated with a final average standard deviation of split frequencies of less than 0.01. Phylogenetic trees of BA and ML analyses were found to be highly similar in topology, and the ML tree is represented in Figure 1. ML bootstrap support (BS) ≥ 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 were labelled along the branches, while branches with BS ≥ 70% and PP ≥ 0.98 were considered to be significant.

Figure 1.

Phylogram of the best ML trees of the Hypoxylon species from an analysis based on multi-gene alignment of ITS-LSU-RPB2-β-tubulin. ML bootstrap support (BS) ≥ 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 are labelled above or below the respective branches (BS/PP). Species in bold were sequenced in this study.

Multi-gene phylogeny shows that our new species are clustered within the clades H2 and H3. Hypoxylon damuense and H. zangii are phylogenetically well differentiated. Hypoxylon damuense clustered with H. hypomiltum Mont. and H. wujiangense Y.H. Pi, Q.R. Li in a full support subclade (BS = 100%, PP = 1) in clade H2. Hypoxylon zangii clustered together with H. guilanense Pourmogh., C. Lamb. and H. texense Kuhnert, Sir in a full support subclade as a sister to H. rubiginosum (Pers.) Fr. Hypoxylon medogense formed a subclade with H. erythrostroma J.H. Mill. with full support in clade H3. The phylogenetic tree shows that Hypoxylon is a paraphyletic group with other genera embedded (e.g., Annulohypoxylon, Daldinia, and Hypomontagnella).

3.2. Taxonomy

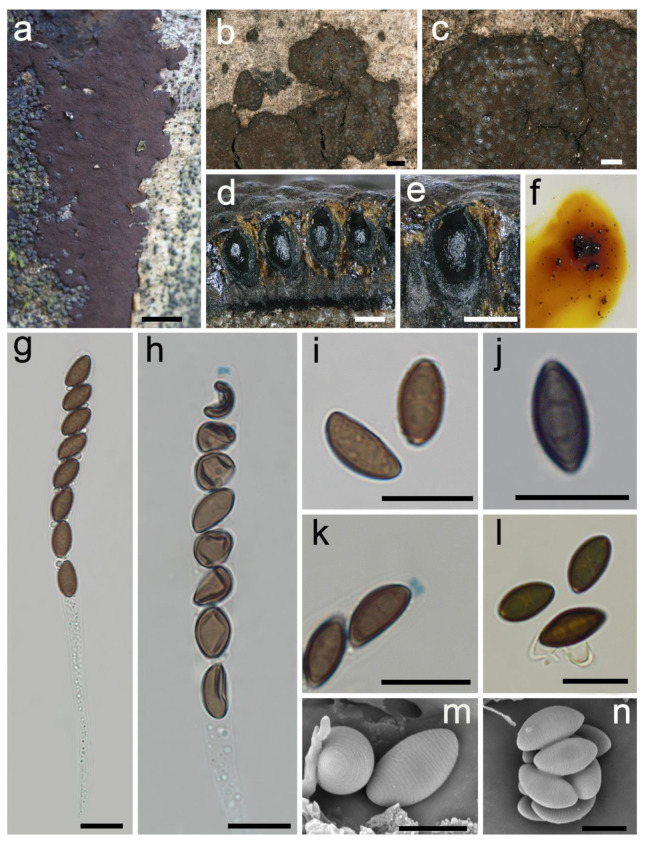

Hypoxylon damuense Hai X. Ma, Z.K. Song and Y. Li, sp. nov., Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hypoxylon damuense (holotype FCATAS 4207). (a,b) Stromata on the bark of dead wood. (c) Stromatal surface. (d,e) Stroma in vertical section showing perithecia and ostioles. (f) KOH-extractable pigments. (g) Asci in water. (h) Asci in Melzer’s reagent. (i) Ascospores in water. (j) Ascospore in 10% KOH showing germ slit. (k) Apical apparatus in Melzer’s reagent. (l) Ascospores in 10% KOH. (m,n) Ascospores under SEM. Scale bars: (a) = 1 cm; (b) = 1000 µm; (c) = 500 µm; (d,e) = 200 µm; (g–l) = 10 µm; (m,n) = 5 µm.

MycoBank: MB 843581

Diagnosis. Differs from H. rubiginosum in its larger asci, light-brown to brown ascospores with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation and most of the perispore indehiscent. Differs from H. hypomiltum in its smaller perithecia, larger asci and apical apparatus. Differs from H. wujiangense in its larger stromata and stromatal KOH-extractable pigments.

Etymology. Damuense (Lat.): referring to the holotype locality of species in Damu Township.

Holotype. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Damu Township, Kabu Village, 29°38′42″ N, 95°37′44″ E, alt. 1280 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 2 October 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ207 (FCATAS 4207).

Teleomorph. Stromata pulvinate to effused-pulvinate, 1–9 cm long × 0.4–2 cm broad × 0.6–0.9 mm thick; with inconspicuous to conspicuous perithecial mounds; surface Bay (6), Rust (39) and Livid Purple (81), exposing black subsurface layer when colored coating worn off; with yellow-brown granules immediately beneath the surface and between perithecia; yielding luteous (12) and ochreous (44) to fulvous (43) KOH-extractable pigments; tissue below the perithecial layer black, 0.1–0.46 mm thick. Perithecia ovoid, black, 0.16–0.3 mm broad × 0.3–0.45 mm high. Ostioles umbilicate, opening lower than the stromatal surface or at the same level as the stromatal surface. Asci cylindrical with eight obliquely uniseriate ascospores, long-stipitate, 102–242 µm total length, the spore-bearing portion 60–72 µm long × 6.2–8.6 µm broad, and stipes 41–174 µm long, with amyloid apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, discoid, 0.8–1.5 µm high × 1.6–2.4 µm broad. Ascospores light-brown to brown, unicellular, ellipsoid-inequilateral, with narrowly rounded ends, 8.2–10.5 × 4.1–5.5 µm (n = 60, M = 9.2 × 4.8 µm), with straight spore-length germ slit on the convex side; most of the perispore indehiscent in 10% KOH, occasionally dehiscent, with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation in SEM; epispore smooth.

Additional specimens examined. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Damu Township, Kabu Village, 29°38′48″ N, 95°37′46″ E, alt. 1310 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 2 October 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ321(FCATAS 4321).

Note. Hypoxylon damuense was found in the subtropics, and characterized by large pulvinate stromata, long asci stipes, amyloid apical apparatus, light-brown to brown ascospores with straight germ slit, most of the perispore indehiscent in 10% KOH, with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation. The new species is quite similar to H. rubiginosum in ascospore dimensions and KOH-extractable pigments, but the latter has darker colored ascospores, smaller asci (100–170 µm total length), dehiscent perispores and smooth or with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation. Hypoxylon rubiginosum sensu stricto was always discovered in the temperate northern hemisphere except for samples reported in Florida [12,15,48]. Moreover, the status of H. damuense as a new species is also supported in the phylogenetic trees, where it appears distant from H. rubiginosum.

Although phylogenetic analyses showed that H. damuense clustered with H. hypomiltum and H. wujiangense in a clade with strong supported values (100%/1), there are distinct morphological differences among them. Hypoxylon hypomiltum differs in having larger perithecia ((0.2–)0.3–0.5 mm broad × 0.5–0.7 mm high), smaller asci (90–132(–145) µm total length), smaller apical apparatus (0.3–0.6 µm high × 1.2–1.5 µm broad) and slightly oblique to sigmoid germ slit [12]. Hypoxylon wujiangense can be distinguished by its smaller stromata with white pruina surface, Sienna (8) KOH-extractable pigments and larger apical apparatus 1.5–2 µm high × 2.5–3 µm broad [19].

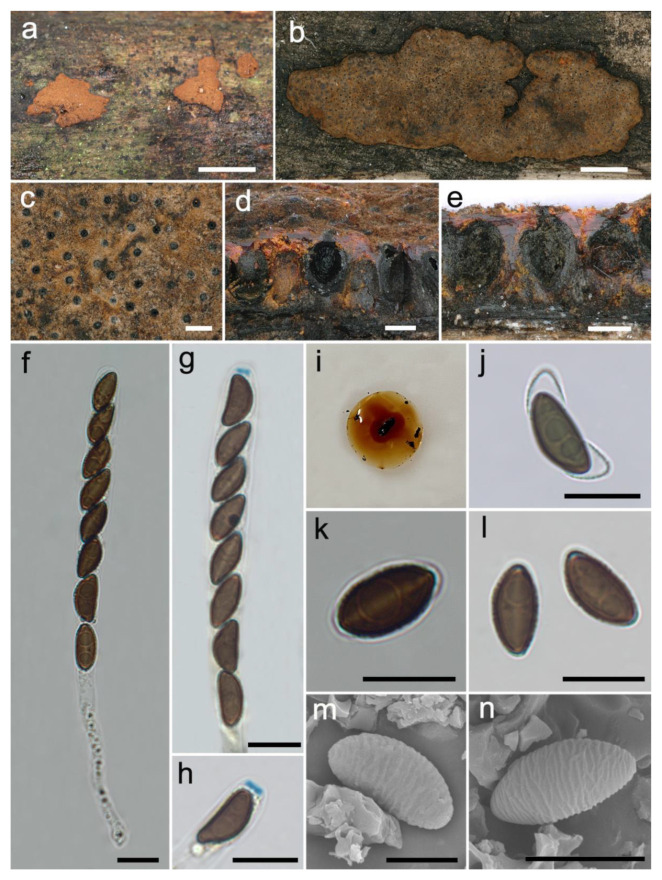

Hypoxylon medogense Hai X. Ma, Z.K. Song and Y. Li, sp. nov., Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Hypoxylon medogense (holotype FCATAS 4061). (a,b) Stromata on the bark of dead wood. (c) Stromatal surface. (d,e) Stroma in vertical section showing perithecia and ostioles. (f) Asci in water. (g) Asci in Melzer’s reagent. (h) Apical apparatus in Melzer’s reagent. (i) KOH-extractable pigments. (j) Ascospore in 10% KOH. (k) Ascospore in water showing germ slit. (l) Ascospores in water. (m,n) Ascospore under SEM. Scale bars: (a) = 1 cm; (b) = 2 mm; (c–e) = 200 µm; (f–h,j–l) = 10 µm; (m) = 5 µm; (n) = 8 µm.

MycoBank: MB 843582

Diagnosis. Differs from H. erythrostroma in its larger ascospores with straight spore-length germ slit and very conspicuous coil-like perispore ornamentation. Differs from H. laschii in ovoid to obovoid perithecia, shorter asci, and larger ascospores with very conspicuous coil-like perispore ornamentation.

Etymology. Medogense (Lat.): referring to the holotype locality of species in Medog county.

Holotype. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Dexing Township, Deguo village, 29°24′58″ N, 95°23′6″ E, alt. 814 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 25 September 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ61 (FCATAS 4061).

Teleomorph. Stromata plane, pulvinate to effused-pulvinate, 3.9–16.5 cm long × 2.5–6.2 cm broad × 0.52–0.72 mm thick; with inconspicuous to conspicuous perithecial mounds; surface cinnamon (62), fulvous (43), ochreous (44) and bay (6); with orange or reddish-orange granules immediately beneath the surface and between perithecia; yielding amber (47), orange (7) or scarlet (5) KOH-extractable pigments; tissue below the perithecial layer inconspicuous, black. Perithecia ovoid to obovoid, black, 0.16–0.3 mm broad × 0.25–0.4 mm high. Ostioles with conical black papillae, opening higher than the stromatal surface. Asci cylindrical, eight-spored, uniseriate, 91–142 µm total length, the spore-bearing portion 60–79 µm long × 6.9–9.4 µm broad, and stipes 25–85 µm long, with amyloid apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, discoid, 0.9–1.4 µm high × 2.4–2.9 µm broad. Ascospores brown to dark brown, unicellular, ellipsoid-inequilateral, with narrowly rounded ends, 9.9–12.8 × 4.6–7 µm (n = 60, M = 11.1 × 5.7 µm), with straight spore-length germ slit on the convex side; perispore dehiscent in 10% KOH, with very conspicuous coil-like ornamentation in SEM; epispore smooth.

Additional specimens examined. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Dexing Township, Deguo village, 29°25′28″ N, 95°23′26″ E, alt. 808 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 25 September 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ320 (FCATAS 4320).

Note.Hypoxylon medogense is characterized by having a bright orange red waxy layer beneath the surface, orange (7) or scarlet (5) KOH-extractable pigments, ostioles higher than the stromatal surface, brown to dark brown ascospores with straight germ slit and dehiscent perispore with very conspicuous coil-like ornamentation. Although the phylogenetic trees (Figure 1 and Figure S1) show that H. medogense and H. erythrostroma are closely related, as well as similar to each other in stromatal morphology and KOH-extractable pigments, H. erythrostroma was originally described and illustrated by Miller (1933) from Florida, and can be distinguished from H. medogense by having smaller ascospores (6.5–9.5 × 3–4.5 µm) and a shorter spore-bearing portion of asci (40–50 µm). Ju and Rogers [12] reexamined the isotype of H. erythrostroma (GAM 2374) from the USA and other specimens from Brazil, French Guiana, Madagascar, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, and Puerto Rico, and found that the fungi has smaller ascospores ((7–)7.5–9.5 × 3–4.5 µm) with sigmoid germ slit spore-length and inconspicuous coil-like perispore ornamentation; the species was also reported in Guadeloupe (French West Indies) by Fournier et al. [10].

Notably, Hypoxylon medogense shows morphological similarities to H. crocopeplum Berk., M.A. Curtis and H. laschii Nitschke in stromatal morphology. Hypoxylon crocopeplum can be distinguished by obovoid to long tubular perithecia (0.1–0.3(–0.4) mm broad × 0.2–1.5 mm high), longer asci ((100–)120–205(–217) µm total length) and slightly larger ascospores ((9–)9.5–15(–17.5) × 4–7(–7.5) µm) with inconspicuous to conspicuous coil-like perispore ornamentation. Hypoxylon laschii has longer asci (165–190 µm total length) and smaller ascospores (8–10 × 3.5–4.5 µm) with no perspore ornamentation [12]. In the phylogenetic trees, H. medogense is distant from the two species.

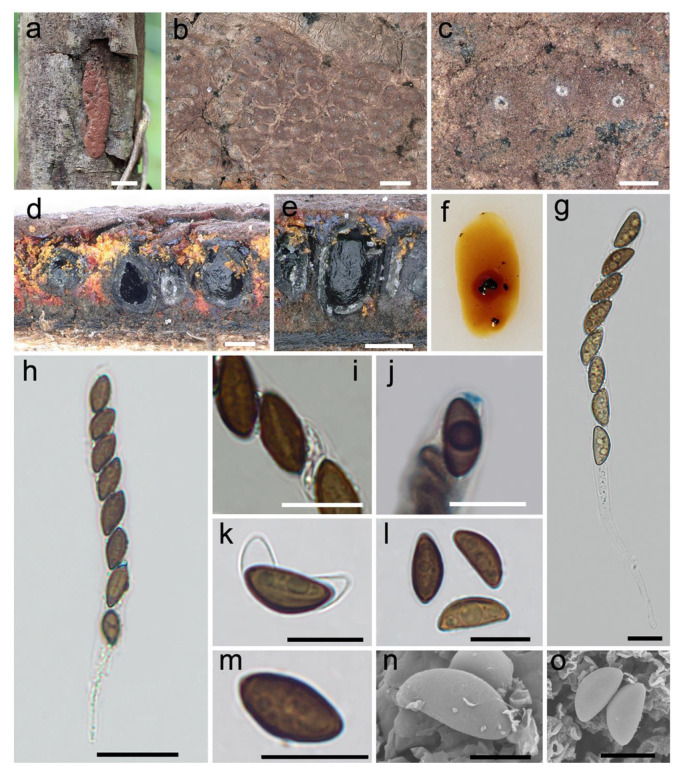

Hypoxylon zangii Hai X. Ma, Z.K. Song and Y. Li, sp. nov., Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Hypoxylon zangii (holotype FCATAS 4029). (a) Stroma on the bark of dead wood. (b,c) Stromatal surface. (d,e) Stroma in vertical section showing perithecia and ostioles. (f) KOH-extractable pigments. (g,h) Asci in water. (i) Ascospores in water showing germ slit. (j) Apical apparatus in Melzer’s reagent. (k) Ascospore in 10% KOH. (l,m) Ascospores in water. (n,o) Ascospores under SEM. Scale bars: (a) = 1 cm; (b) = 1 mm; (c–e) = 200 µm; (g,i–m) = 10 µm; (h) = 20 µm; (n) = 5 µm; (o) = 8 µm.

MycoBank: MB 843580

Diagnosis. Differs from H. fendleri and H. retpela in its smaller ascospores. Differs from H. rubiginosum in its stromatal granules and a subtropical distribution. Differs from H. texense in its stromatal KOH-extractable pigments and larger ascospores. Differs from H. guilanense in its stromatal morphology.

Etymology.Zangii (Lat.): referring in honor to Chinese mycologist Dr. Zang Mu, who is also the author of “Field Records in the Mountains and Valleys: Discovery Journey to the Third Pole—Notes and Drawings of Zang Mu Scientific Expeditions”.

Holotype. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Yarlung Zangbo River, the large bend of Linduo, 29°27′52″ N, 95°26′39″ E, alt. 781 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 24 September 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ29 (FCATAS 4029).

Teleomorph. Stromata effused-pulvinate, 1.2–4.1 cm long × 0.8–1 cm broad × 0.25–0.45 mm thick; with conspicuous perithecial mounds; surface livid red (56) and vinaceous (57); with orange or reddish orange granules immediately beneath the surface and between perithecia; yielding amber (47), fulvous (43) and sienna (8) KOH-extractable pigments; tissue below the perithecial layer inconspicuous, brown. Perithecia spherical, ovoid to obovoid, black, 0.2–0.4 mm broad × 0.3–0.5 mm high. Ostioles umbilicate, sometimes overlain with conspicuous white substance, opening lower than the stromatal surface. Asci cylindrical, eight-spored, uniseriate, 85–145 µm total length, the spore-bearing portion 65–92 µm long × 7.1–10.9 µm broad, and stipes 12–66 µm long, with amyloid apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, discoid, 0.8–1.3 µm high × 2–2.9 µm broad. Ascospores light-brown to brown, unicellular, ellipsoid-inequilateral, with slightly acute to narrowly rounded ends, 10.9–14.6 × 4.8–6.4 µm (n = 60, M = 12.2 × 5.5 µm), with straight spore-length germ slit on the convex side; perispore dehiscent in 10% KOH, with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation in SEM; epispore smooth.

Additional specimens examined. CHINA: Tibet Autonomous Region, Medog County, Yarlung Zangbo River, the larger bend of Linduo, 29°27′35″ N, 95°26′32″ E, alt. 780 m, saprobic on the bark of dead wood, 24 September 2021, Haixia Ma, Col. XZ319 (FCATAS 4319).

Note. The stromatal morphology of H. zangii is similar to H. fendleri Berk. ex Cooke, H. retpela Van der Gucht, Van der Veken and H. rubiginosum. However, H. fendleri differs by having slightly thicker stromata at 0.5–0.8 mm, smaller ascospores ((8–)9–12 × 4–5.5 µm) with sigmoid germ slit spore-length, while H. retpela has thicker stromata at 0.5–0.8 mm, and smaller ascospores ((9–)9.5–12 × 4.5–5 µm) with very conspicuous coil-like ornamentation [12]. Hypoxylon rubiginosum can also be distinguished by its yellowish-brown or brown stromatal granules, thicker stromata (0.5–1.2(–1.5) mm) and smaller ascospores ((8–)9–12 × 4–5.5 µm). In addition, H. rubiginosum prefers to distribute in the northern temperate region, while H. zangii was found in subtropical region [12,15,47]. These three species are distant from H. zangii in the phylogenetic trees (Figure 1).

Hypoxylon zangii clustered with H. guilanense and H. texense in a strong support clade in the phylogenetic trees. Hypoxylon texense shows morphological similarities to H. zangii with reddish-orange stromatal granules, but differs in having rust (39) to dark brick (86) instead of amber (47), fulvous (43) and sienna (8) KOH-extractable pigments, and smaller ascospores ((9–)9.5–12 × 4.5–5 µm) with straight to slightly sigmoid germ slit spore-length [37]. Hypoxylon guilanense differs from H. zangii in having hemispherical to pulvinate stromata with sienna (8), umber (9) to buff (45) surface colors, with conspicuous perithecial mounds, and slightly larger ascospores (12–15 × 5–6 µm) with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation [15].

Dichotomous key to Hypoxylon species from China

and related species worldwide

1. Ascospores nearly equilateral ............................................................................................. 2

1. Ascospores inequilateral ...................................................................................................... 8

2. Ostiolar barely to slightly higher than the stromatal surface ......................................... 3

2. Ostioles lower than the stromatal surface ......................................................................... 4

3. Perithecia spherical, (0.2–)0.3–0.4 mm broad .................................................. H. croceum

3. Perithecia spherical to tubular, 0.3–0.6 mm broad × 0.4–0.8 mm high. H. parksianum

4. Perispore dehiscent in 10% KOH ............................................................... H. hypomiltum

4. Perispore indehiscent in 10% KOH .................................................................................... 5

5. Perithecia tubular to long tubular ....................................................................................... 6

5. Perithecia obovoid ................................................................................................................ 7

6. KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ................................................... H. cinnabarinum

6. KOH-extractable pigments greenish yellow (16), dull green (70), or dark green

(21) ...................................................................................................................... H. investiens

7. Stromatal surface brown vinaceous (84), sepia (63), or chestnut (40); without apparent

KOH-extractable pigments or with dilute grayish sepia (106) to blackish

pigments ........................................................................................................ H. dieckmannii

7. Stromatal surface fawn (87) or umber (9); KOH-extractable pigments hazel

(88) ................................................................................................................... H. gilbertsonii

8. Ostiolar barely to slightly higher than the stromatal surface ......................................... 9

8. Ostioles lower than the stromatal surface ....................................................................... 15

9. Perithecia tubular.................................................................................... H. lienhwacheense

9. Perithecia spherical, ovoid to obovoid ............................................................................. 10

10. Stromatal granules black ............................................................................... H. hainanense

10. Stromatal granules colored ................................................................................................ 11

11. Stromata glomerate; KOH-extractable pigments hazel (88) .................. H. lenormandii

11. Stromata pulvinate; KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ......................................... 12

12. Sigmoid germ slit ................................................………......................... H. erythrostroma

12. Straight germ slit ................................................................................................................. 13

13. Perispore with very conspicuous coil-like ornamentation ....................... H. medogense

13. Perispore smooth or with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation .............................. 14

14. Stromata pulvinate to discoid, erumpent, usually encircled with ruptured plant tissue;

perithecia 0.2–0.4(–0.5) mm diam ............................................................ H. laschii

14. Stromata pulvinate to effused-pulvinate, sometimes hemispherical, plane; perithecia

0.1–0.2 mm diam ................................................................................................... H. rutilum

15. Sigmoid germ slit .........................................………........................………………… 16

15. Straight or slightly sigmoid germ slit ............................................................................... 19

16. Perispore with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation ................... H. cyclobalanopsidis

16. Perispore smooth or with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation .............................. 17

17. Sigmoid germ slit much less than spore-length; stromata glomerate, with conspicuous

perithecial mounds; KOH-extractable pigments pure yellow (14) with citrine (13) tone,

greenish olivaceous (90), or orange (7) ............................. H. musceum

17. Sigmoid germ slit spore-length; stromata pulvinate or effused-pulvinate, with inconsp

icuous to conspicuous perithecial mounds; KOH-extractable pigments with other

colors ..................……................................................................................................. 18

18. KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ..................……..................................... H. fendleri

18. KOH-extractable pigments vinaceous purple (101) ............…..................... H. fuscoides

19. Perispore infrequently dehiscent in 10% KOH .................…….....................……......... 20

19. Perispore dehiscent in 10% KOH .................…….........................…................................ 22

20. Stromata saprobic on surface of dead bamboo ................................... H. wuzhishanense

20. Stromata saprobic on the bark of dicot wood ................................................................. 21

21. Ascospores light-brown to brown, 8.2–10.5 × 4.1–5.5 µm, with straight germslit spore-

length ....................................................................................................... H. damuense

21. Ascospores brown to dark brown, (10–)10.5–11.5(–12.5) × 5–6.5 µm, with straight germ

slit slightly less than spore-length .............................................................. H. dengii

22. Perispore with conspicuous coil-like ornamentation .................................................... 23

22. Perispore smooth or with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation .............................. 28

23. Stromata pulvinate to effused-pulvinate ......................................................................... 24

23. Stromata glomerate or hemispherical .............................................................................. 25

24. Perithecia tubular to long tubular or obovoid, 0.2–0.3 mm broad × 0.6–0.9 mm high;

ascospores light brown to dark brown, 10.3–13.6 × (4.2–) 4.7–6.1 μm, with conspicuous

straight germ slit .................................................................... H. jianfengense

24. Perithecia spherical to obovoid, 0.2–0.3 mm broad × 0.2–0.5 mm high; ascospores

brown to dark brown, (9–)9.5–12 × 4.5–5 μm, with straight to slightly sigmoid germ

slit ............................................................................................................................. H. retpela

25. KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ............................................................................. 26

25. KOH-extractable pigments with other colors ................................................................. 27

26. Stromata glomerate to pulvinate; stromatal granules dull yellow

or rust ............................................................................................................. H. baihualingense

26. Stromata hemispherical to pulvinate; stromatal granules scarlet (5) to orange

(7) ....................................................................................................................... H. guilanense

27. Stromatal granules pale brown to dull reddish-brown; KOH-extractable pigments pale

luteous (11), honey (60) and ochreous (44); apical apparatus highly reduced or lacking,

not bluing in Melzer’s reagent; ascospores light-brown to brown, with slightly broad

rounded ends, 8–10.6(–11.1) × 4.1–6.3(–7.1) µm ... H. chrysalidosporum

27. Stromatal granules dull reddish-brown to blackish; KOH-extractable pigments

isabelline (65) or amber (47); apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent; ascospores

brown to dark brown, with narrowly rounded ends, 9.5–13(–14.5) × 4.5–6.5

µm ........................................................................................................................... H. duranii

28. KOH-extractable pigments greenish to olivaceous ........................................................ 29

28. KOH-extractable pigments with other colors ................................................................. 33

29. Stromata pulvinate to effused-pulvinate ......................................................................... 30

29. Stromata glomerate or hemispherical .............................................................................. 31

30. Ascospores brown to dark brown, 8.5–13.5 × 4–6 μm .......................... H. anthochroum

30. Ascospores light brown to brown, 5.5–8 × 2.5–3.5 μm ........................... H. brevisporum

31. Apical apparatus highly reduced or lacking, not bluing in Melzer’s rea

gent .................................................................................................................. H. notatum

31. Apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent .................................................................. 32

32. Perithecia spherical to obovoid, 0.1–0.3(–0.4) mm broad × 0.2–0.5 mm high; slightly

sigmoid germ slit ................................................................................................... H. fuscum

32. Perithecia long tubular, 0.3–0.6 mm broad × (0.6–)0.8–2 mm high; straight germ

slit ................................................................................................................. H. placentiforme

33. Stromata hemispherical ...................................................................................................... 34

33. Stromata pulvinate to effused-pulvinate ......................................................................... 37

34. Perithecia long tubular .......................................................................... H. haematostroma

34. Perithecia spherical to obovoid ......................................................................................... 35

35. KOH-extractable pigments amber (47) with greenish yellow (16) tone, or greenish

yellow (16) with citrine (13) tone ................................................................ H. perforatum

35. KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ............................................................................. 36

36. Apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, 0.8–1.2 μm high × 2.2–2.8 μm broad;

ascospores (10.5–)11–15 × 5–6.5(–7) μm ....................................................... H. fragiforme

36. Apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, 0.4–0.8 μm high × 1.2–2 μm broad;

ascospores 7–9.5(–10) × 3–4.5 μm ................................................................. H. howeanum

37. Perithecia tubular ................................................................................................................ 38

37. Perithecia spherical to obovoid ......................................................................................... 42

38. Stromatal granules black; KOH-extractable pigments dark livid (80) .... H. lividicolor

38. Stromatal granules colored; KOH-extractable pigments with other colors ............... 39

39. KOH-extractable pigments pure yellow (14) or amber (47) ......................... H. trugodes

39. KOH-extractable pigments orange (7) ............................................................................. 40

40. Apical apparatus bluing in Melzer’s reagent, 0.2–0.5 μm high × 1–1.5 μm

broad ................................................................................................................... H. jecorinum

40. Apical apparatus lightly bluing or bluing in Melzer’s reagent, more than 1.5 μm

broad ..................................................................................................................................... 41

41. Perithecia spherical, obovoid to long tubular, up to 1.5 mm high; ascospores (9–)9.5

–15(–17.5) × 4–7(–7.5) μm; Virgariella-like conidiogenous structure

........................................................................................................ H. crocopeplum

41. Perithecia obovoid to tubular, up to 0.7 mm high; ascospores 7–11 × 3.5–5 μm;

Nodulisporium-like conidiogenous structure ................................................ H. subgilvum

42. Stromata saprobic on dead bamboo .......................................................... H. pilgerianum

42. Stromata saprobic on dicot wood ..................................................................................... 43

43. Ascospores 15.5–22.9(–23.6) × 7.3–10.6 μm ....................................................... H. larissae

43. Ascospores length less than 15 µm ................................................................................... 44

44. Perithecia subglobose, 0.5–0.7 mm broad; straight or slightly sigmoid germ slit nearly

spore-length ...................................................................................... H. wujiangense

44. Perithecia less than 0.5 mm broad; straight germ slit spore-length ............................. 45

45. Stromatal granules orange or reddish orange; ascospores light-brown ..................... 46

45. Stromatal granules yellowish-brown or dull purplish-brown; ascospores dark

brown .................................................................................................................................... 47

46. KOH-extractable pigments rust (39) to dark brick (86); ascospore (8.7–)9.1–10.8(–11.5)

× (4.0–)4.5–5.4 μm .................................................................................................. H. texense

46. KOH-extractable pigments amber (47), fulvous (43) and sienna (8); ascospore 10.9–14.6

× 4.8–6.4 µm ............................................................................................. H. zangii

47. Stromatal granules yellowish-brown or brown; perithecia 0.2–0.5 mm broad × 0.3–0.6

mm high; smooth or with inconspicuous coil-like ornamentation perispore; Periconiella-

like conidiogenous structure .................................................. H. rubiginosum

47. Stromatal granules dull purplish-brown; perithecia 0.1–0.2 mm broad × 0.2–0.3 mm

high; smooth perispore; Nodulisporium-like conidiogenous structure

.............................................................................................. H. vinosopulvinatum

4. Discussion

In the present study, three species of Hypoxylon from Medog in China, H. damuense, H. medogense, and H. zangii, are described as new species based on molecular analyses and morphological features. Phylogenetic analyses on the species of Hypoxylon presented confirmed that Hypoxylon is a polyphyletic genus. The species analyzed appeared mainly distributed in six separate clades (except H. papillatum Ellis, Everh. and H. dieckmannii Theiss.). Hypoxylon damuense and H. zangii were clearly separated from other sampled species of Hypoxylon and from each other in the clade H2, and H. medogense was included in clade H3 containing H. fragiforme (Pers.) J. Kickx f., the type species of the genus. The phylogenetic tree shows that the classification of Hypoxylon is confusing. It did not suggest any apparent correlation in morphological features with the distribution of species in the phylogenetic trees. Therefore, more collections, more gene sequences and new taxonomic features, as well as the application of polyphasic taxonomic approaches based on morphological (sexual and asexual), chemotaxonomic, and phylogenetic data of this genus are needed in the further studies. Previously numerous new species have been found in Southwest China [49,50], and present paper confirmed that more known fungal species in the area.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Zhu-nian Wang, Qing-long Wang, Hu-biao Yang, Shi-song Xu (Tropical Crops Genetic Resources Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences), Rong-jie Zhu (Tibet Academy of Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Sciences), and Xue-da Chen (Tibet Agriculture and Animal Husbandry University) for help during field collections. We gratefully acknowledge Guo-dao Liu for his helpful suggestions to improve the nomenclature of the new species. Special thanks to Xiao-wei Qin and Ting-yu Bai (Spice and Beverage Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences) for assistance in micrographs produced by SEM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jof8050500/s1, Figure S1: ML phylogram inferred from ITS-TUB2 sequences. ML bootstrap support (BS) ≥ 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 are labelled above or below the respective branches (BS/PP). Species in bold were sequenced in the this study.

Author Contributions

Z.-K.S., A.-H.Z., Z.-D.L., Z.Q. and H.-X.M. prepared the samples; Z.-K.S. made morphological examinations and performed molecular sequencing; A.-H.Z. performed phylogenetic analyses. Z.-K.S., A.-H.Z. and H.-X.M. wrote the manuscript; Y.L. revised the language of the text; H.-X.M. conceived and supervised the work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 15 March 2022; Table 1). All new taxa were deposited in MycoBank (https://www.mycobank.org/, accessed on 12 March 2022; MycoBank identifiers follow new taxa).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31972848, 31770023), and Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund for Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences (No. 1630032022001, 1630052022003, 1630052022042).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stadler M., Fournier J. Pigment chemistry, taxonomy and phylogeny of the Hypoxyloideae (Xylariaceae) Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2006;23:160–170. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(06)70037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wendt L., Sir E.B., Kuhnert E., Heitkämper S., Lambert C., Hladki A.I., Romero A.I., Luangsaard J.J., Srikitikulchai P., Per D., et al. Resurrection and emendation of the Hypoxylaceae, recognised from a multigene phylogeny of the Xylariales. Mycol. Prog. 2018;17:115–154. doi: 10.1007/s11557-017-1311-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhnert E., Navarro-Muñoz J.C., Becker K., Stadler M., Collemare J., Cox R.J. Secondary metabolite biosynthetic diversity in the fungal family Hypoxylaceae and Xylaria hypoxylon. Stud. Mycol. 2021;99:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2021.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hyde K.D., Norphanphoun C., Maharachchikumbura S.S.N., Bhat D.J., Jones E.B.G., Bundhun D., Chen Y.J., Bao D.-F., Boonmee S., Calabon M., et al. Refined families of Sordariomycetes. Mycosphere. 2020;11:305–1059. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pažoutová S., Follert S., Bitzer J., Keck M., Surup F., Šrůtka P., Holuša J., Stadler M. A new endophytic insect-associated Daldinia species, recognised from a comparison of secondary metabolite profiles and molecular phylogeny. Fungal Divers. 2013;60:107–123. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0238-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pažoutová S., Šrůtka P., Holuša J., Chudickova M., Kolarik M. The phylogenetic position of Obolarina dryophila (Xylariales) Mycol. Prog. 2010;9:501–507. doi: 10.1007/s11557-010-0658-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pažoutová S., Šrůtka P., Holuša J., Chudíčková M., Kolařík M. Diversity of xylariaceous symbionts in Xiphydria woodwasps: Role of vector and a host tree. Fungal Ecol. 2010;3:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2010.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers J.D. Thoughts and musings on tropical Xylariaceae. Mycol. Res. 2000;104:1412–1420. doi: 10.1017/S0953756200003464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhnert E., Fournier J., Per D., Luangsaard J.J.D., Stadler M. New Hypoxylon species from Martinique and new evidence on the molecular phylogeny of Hypoxylon based on ITS rDNA and β-tubulin data. Fungal Divers. 2014;64:181–203. doi: 10.1007/s13225-013-0264-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fournier J., Lechat C., Courtecuisse R. The genus Hypoxylon (Xylariaceae) in Guadeloupe and Martinique (French West Indies) Ascomycete. Org. 2016;7:145–212. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sir E.B., Kuhnert E., Lambert C., Hladki A.I., Romero A.I., Stadler M. New species and reports of Hypoxylon from Argentina recognized by a polyphasic approach. Mycol. Prog. 2016;15:42. doi: 10.1007/s11557-016-1182-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ju Y.M., Rogers J.D. A Revision of the Genus Hypoxylon. American Phytopathological Society Press; St. Paul, MN, USA: 1996. p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh H., Ju Y.M., Rogers J.D. Molecular phylogeny of Hypoxylon and closely related genera. Mycologia. 2005;97:844–865. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stadler M. Importance of secondary metabolites in the Xylariaceae as parameters for assessment of their taxonomy, phylogeny, and functional biodiversity. Curr. Res. Envion. Appl. Mycol. 2011;1:75–133. doi: 10.5943/cream/1/2/1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pourmoghaddam M.J., Lambert C., Surup F., Khodaparast S.A., Krisai-Greilhuber I., Voglmayr H., Stadler M. Discovery of a new species of the Hypoxylon rubiginosum complex from Iran and antagonistic activities of Hypoxylon spp. Against the Ash Dieback pathogen, Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, in dual culture. MycoKeys. 2020;66:105–133. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.66.50946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Index Fungorum. [(accessed on 23 March 2022)]. Available online: http://www.indexfungorum.org/names/names.asp.

- 17.Chi S.Q., Xu J., Lu B.S. Three New Chinese Records of Hypoxylon. J. Fungal Res. 2016;14:218–221. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma H.X., Qiu J.Z., Xu B., Li Y. Two Hypoxylon species from Yunnan Province based on morphological and molecular characters. Phytotaxa. 2018;376:027–036. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.376.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pi Y.H., Zhang X., Liu L.L., Long Q.D., Shen X.C., Kang Y.Q., Hyde K.D., Boonmee S., Kang J.C., Li Q.R. Contributions to species of Xylariales in China—4 Hypoxylon wujiangensis sp. nov. Phytotaxa. 2020;455:21–30. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.455.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma H., Song Z., Pan X., Li Y., Yang Z., Qu Z. Multi-gene phylogeny and taxonomy of Hypoxylon (Hypoxylaceae, Ascomycota) from China. Diversity. 2022;14:37. doi: 10.3390/d14010037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Z.K., Pan X.Y., Li C.T., Ma H.X., Li Y. Two new species of Hypoxylon (Hypoxylaceae) from China based on morphological and DNA sequence data analyses. Phytotaxa. 2022;538:213–224. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.538.3.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng M., Zhu R.J., Zhao G.F. Utilization of wild plant resources and development suggestions of agricultural industry in Motuo tropical area of Tibet. Chin. J. Trop. Agric. 2022;42:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friebes G., Wendelin I. Studies on Hypoxylon ferrugineum (Xylariaceae), a rarely reported species collected in the urban area of Graz (Austria) Ascomycete. Org. 2016;8:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rayner R.W. A Mycological Colour Chart. Cmi. & British Mycological Society Kew; London, UK: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhnert E., Sir E.B., Lambert C., Hyde K.D., Hladki A.I., Romero A.I., Rohde M., Stadler M. Phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic resolution of the genus Annulohypoxylon (Xylariaceae) including four new species. Fungal Divers. 2017;85:1–43. doi: 10.1007/s13225-016-0377-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardes M., Bruns T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes-application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Eco. 1993;2:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O‘donnell K., Cigelnik E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997;7:103–116. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White T.J., Bruns T.D., Lee S., Taylor J.W. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics—science direct. PCR Protoc. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilgalys R., Hester M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y.J., Whelen S., Hall B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: Evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999;16:1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981;17:368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cedeño-Sanchez M., Wendt L., Stadler M., Mejía L.C. Three new species of Hypoxylon and new records of Xylariales from Panama. Mycosphere. 2020;11:1457–1476. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stadler M., Læssøe T., Fournier J., Decock C., Schmieschek B., Tichy H.V., Peršoh D. A polyphasic taxonomy of Daldinia (Xylariaceae) Stud. Mycol. 2014;77:1–143. doi: 10.3114/sim0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lambert C., Wendt L., Hladki A.I., Stadler M., Sir E.B. Hypomontagnella (Hypoxylaceae): A new genus segregated from Hypoxylon by a polyphasic taxonomic approach. Mycol. Prog. 2019;18:187–201. doi: 10.1007/s11557-018-1452-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vicente T.F.L., Goncalves M.F.M., Brandao C., Fidalgo C., Alves A. Diversity of fungi associated with macroalgae from an estuarine environment and description of Cladosporium rubrum sp. nov. and Hypoxylon aveirense sp. nov. Int. J Syst. Evol. Micr. 2021;71:004630. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambert C., Pourmoghaddam M.J., Cedeño‒Sanchez M., Surup F., Khodaparast S.A., Krisai-Greilhuber I., Voglmayr H., Stradal T.E.B., Stadler M. Resolution of the Hypoxylon fuscum complex (Hypoxylaceae, Xylariales) and discovery and biological characterization of two of its prominent secondary metabolites. J. Fungi. 2021;7:131. doi: 10.3390/jof7020131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sir E.B., Becker K., Lambert C., Bills G.F., Kuhnert E. Observations on Texas hypoxylons, including two new Hypoxylon species and widespread environmental isolates of the H. croceum complex identified by a polyphasic approach. Mycologia. 2019;11:832–856. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2019.1637705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sir E.B., Kuhnert E., Surup F., Hyde K.D., Stadler M. Discovery of new mitorubrin derivatives from Hypoxylon fulvosulphureum sp. nov. (Ascomycota, Xylariales) Mycol. Prog. 2015;14:28. doi: 10.1007/s11557-015-1043-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vu D., Groenewald M., Vries M., Gehrmann T., Stielow B., Eberhardt U., Al-Hatmi A., Groenewald J.Z., Cardinali G., Houbraken J., et al. Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud. Mycol. 2019;92:135–154. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bitzer J., Læssøe T., Fournier J., Kummer V., Decock C., Tichy H.V., Piepenbring M., Peršoh D., Stadler M. Affinities of Phylacia and the daldinoid Xylariaceae, inferred from chemotypes of cultures and ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:251–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker K., Lambert C., Wieschhaus J., Stadler M. Phylogenetic assignment of the fungicolous Hypoxylon invadens (Ascomycota, Xylariales) and investigation of its secondary metabolites. Microorganisms. 2020;8:1397. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8091397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuhnert E., Surup F., Sir E.B., Lambert C., Hyde K.D., Hladki A.I., Romero A.I., Stadler M. Lenormandins A—G, new azaphilones from Hypoxylon lenormandii and Hypoxylon jaklitschii sp. nov., recognised by chemotaxonomic data. Fungal Divers. 2015;71:165–184. doi: 10.1007/s13225-014-0318-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dai D.Q., Phookamsak R., Wijayawardene N.N., Li W.J., Bhat D.J., Xu J.C., Taylor J.E., Hyde K.D., Chukeatirote E. Bambusicolous fungi. Fungal Divers. 2017;82:1–105. doi: 10.1007/s13225-016-0367-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bills G.F., González-Menéndez V., Martín J., Platas G., Fournier J., Peršoh D., Stadler M. Hypoxylon pulicicidum sp. nov. (Ascomycota, Xylariales), a pantropical insecticide-producing endophyte. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stadler M., Kuhnert E., Peršoh D., Fournier J. The Xylariaceae as model example for a unified nomenclature following the “One Fungus-One Name” (1F1N) concept. Mycology. 2013;4:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stadler M., Fournier J., Laessøe T., Chlebicki A., Lechat C., Flessa F., Rambold G., Peršoh D. Chemotaxonomic and phylogenetic studies of Thamnomyces (Xylariaceae) Mycoscience. 2010;51:189–207. doi: 10.1007/S10267-009-0028-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stadler M., Fournier J., Beltrán-Tejera E., Granmo A. The “red Hypoxylons” of the temperate and subtropical Northern Hemisphere. N. Am. Fungi. 2008;3:73–125. doi: 10.2509/naf2008.003.0075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dai Y.C., Yang Z.L., Cui B.K., Wu G., Yuan H.S., Zhou L.W., He S.H., Ge Z.W., Wu F., Wei Y.L., et al. Diversity and systematics of the important macrofungi in Chinese forests. Mycosystema. 2021;40:770–805. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang K., Chen S.L., Dai Y.C., Jia Z.F., Li T.H., Liu T.Z., Phurbu D., Mamut R., Sun G.Y., Bau T., et al. Overview of China’ s nomenclature novelties of fungi in the new century (2000–2020) Mycosystema. 2021;40:822–833. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, accessed on 15 March 2022; Table 1). All new taxa were deposited in MycoBank (https://www.mycobank.org/, accessed on 12 March 2022; MycoBank identifiers follow new taxa).