Abstract

Aim

Inflammatory cytokines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) directly affect cardiac electrophysiology by inhibiting cardiac potassium currents, leading to delay of cardiac repolarisation and QT-prolongation. This may result in lethal arrhythmias. We studied whether RA increases the rate of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in the general population.

Methods

We conducted a nested case–control in a cohort of individuals between 1 June 2001 and 31 December 2015. Cases were OHCA patients from presumed cardiac causes, and were matched with non-OHCA-controls based on age, sex and OHCA date. Cox-regression with time-dependent covariates was conducted to assess the association between RA and OHCA by calculating the HR and 95% CI. Stratified analyses were performed according to sex and presence of cardiovascular diseases. Also, the association between OHCA and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with RA was studied.

Results

We included 35 195 OHCA cases of whom 512 (1.45%) had RA, and 351 950 non-OHCA controls of whom 3867 (1.10%) had RA. We found that RA was associated with increased rate of OHCA after adjustment for cardiovascular comorbidities and use of QT-prolonging drugs (HR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.34). Stratification by sex revealed that increased OHCA rate occurred in women (HR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.16 to 1.50) but not in men (HR: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.28; P value interaction=0.046). OHCA rate of RA was not further increased in patients with cardiovascular disease. Finally, in patients with RA, use of NSAIDs was not associated with OHCA.

Conclusion

In the general population, RA is associated with increased rate of OHCA in women but not in men.

Keywords: Heart Arrest, Epidemiology, Inflammation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Inflammatory cytokines in patients with rheumatoid arthritis directly affects cardiac electrophysiology by inhibiting cardiac potassium currents which largely drives cardiac repolarisation. This may lead to QT-prolongation and increase the susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmias and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are associated with higher rate of OHCA of presumed cardiac cause compared with the general population after adjustments for common OHCA risk factors. Stratification according to sex revealed that this increased OHCA rate occurred in women but not in men.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

A better management and early screening for cardiovascular risk factors is needed in women with rheumatoid arthritis in order to prevent OHCA.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a public health problem that accounts for 50% of all deaths from cardiovascular causes in industrialised countries.1 The majority of such deaths are usually caused by cardiac arrhythmias.2 Part of cardiac arrhythmia and OHCA is explained by known risk factors such as ischaemic heart disease and heart failure.2 However, OHCA risk may also be increased by non-cardiac diseases.3

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) are at increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.4 5 Multiple pathophysiologic changes in RA may result in higher cardiovascular mortality, in particular, development of ischaemic heart disease and heart failure.6 Yet, the short-term mortality (7-day and 30-day) following acute coronary syndrome is higher in patients with RA than non-RA controls, even when type of acute coronary syndrome and relevant comorbidities are taken into account.7 This implies that the higher mortality rates among patients with RA can only be partly explained by increased event severity and that other factors with direct impact on cardiac electrophysiology may explain, at least in part, the higher cardiovascular mortality observed in these patients.8 Indeed, inflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα)) prolong the QT-interval (an indicator of cardiac repolarisation) by impacting cardiac potassium channels.8 9 Accordingly, this may increase the susceptibility to triggered cardiac arrhythmias by early after depolarisations in patients with RA. Women in particular, may be more vulnerable to QT-prolongation because women have less repolarisation reserves than men.10

Using Danish nationwide registries, we studied whether RA is associated with increased rate of OHCA. Because we expected that women may have higher OHCA rate, we stratified our analyses according to sex. Moreover, we evaluated the role of important OHCA risk factors, that is, cardiovascular disease, by studying the association between RA and OHCA in patients with and without cardiovascular comorbidities.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a nested case–control study in a nationwide cohort of individuals between 1 June 2001 and 31 December 2015. Cases were OHCA victims from presumed cardiac causes. Each OHCA case (index-date) was matched with up to 10 non-OHCA controls from the general population based on sex, age and index-date. We used the same study design previously.11

Data sources and definitions

All Danish residents are assigned a unique identification number on birth or immigration. Using this unique identifier, information at an individual level across different nationwide registries can be cross-linked allowing large-scale research with nationwide coverage. The present study was based on data from the following registries: (1) the Danish Cardiac Arrest Registry, (2) the Danish Civil Registration System, (3) the Danish National Patient Register, (4) the National Prescription Register and (5) the Danish Register of Causes of Death.12–16 These registries have been described and used previously.12–16

Patients with OHCA included in this study were drawn from the Danish Cardiac Arrest Registry. The Danish Cardiac Arrest Registry is a nationwide registry that holds information on all OHCAs since June 2001. Since the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) is activated for all clinical emergencies in Denmark and EMS must fill out a case report for every attended OHCA, capture of OHCA is nearly complete. The presumed cause of OHCA was obtained from death certificates and discharge diagnoses. OHCAs with diagnosis codes for cardiac disease, unknown disease or unexpected collapse were classified as being of presumed cardiac cause. The Danish Civil Registration System holds information on demographic variables and was used to obtain information on patients’ age and sex. Information regarding comorbidities was obtained from the Danish Patient Registry, which includes information on all the hospital contacts. Data on diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Disease 10th edition (ICD-10). Information on drugs use was obtained from the National Prescription Register, which contains information on dispensed drug prescriptions classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC). Finally, data on causes of death were retrieved from the Danish Register of Causes of Death.

Exposure of interest and covariates

Patients with RA were identified by using primary and secondary diagnoses registered in the Danish National Patient registry up to 10 years prior to the index date. Cardiovascular comorbidity was identified using hospital diagnosis up to 10 years before the index-date. Additionally, concomitant pharmacotherapy was identified using ATC codes up to 180 days prior to index date as we did previously11 (see online supplemental table 1 for the ICD-10 and ATC codes). For non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), this period was 90 days prior to index date because these drugs are generally prescribed for shorter periods (see online supplemental table 2 for the ATC codes). Finally, diabetes was defined as the use of antidiabetic drugs in the period of 180 days before the index-date, since the diagnosis code of diabetes has a low sensitivity in the Danish registries.

openhrt-2022-001987supp001.pdf (39.2KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

We used a time-dependent Cox proportional hazards regression model to assess the association between RA and the rate of OHCA by calculating the HR and the associated 95% CI. We calculated both crude estimates (univariable analyses) and adjusted estimates (multivariable analysis) by adjusting for important OHCA risk factors (eg, cardiovascular disease and the use of QT-prolong drugs). First, we examined the association between RA and the rate of OHCA in the overall population. Next, we stratified according to sex and the presence of cardiovascular disease. By performing stratified analyses according to cardiovascular disease our original matching was lost, therefore we additionally adjusted for age and sex in our model. The presence of interaction on multiplicative scale between RA and sex, and between RA and cardiovascular disease was estimated by consecutively including the cross-product of the two factors as a variable in the model. Furthermore, we studied whether patient characteristics were different between cases with and without RA. Finally, we studied the association between NSAIDs and OHCA in patients with RA to evaluate the role of NSAIDs, since an association between NSAIDs and OHCA has been reported previously.17

Characteristics of the studied population were described in frequencies and percentages for categorical values and in median and IQR for numerical values. For the present study, we used the same dataset as we did for our previous study.11 Therefore, table 1 with baseline characteristics of the studied population is overlapping with table 1 from our previous study.11

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| Cases (n=35 195) |

Controls (n=351 950) |

|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 72 (62–81) | 72 (62–81) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 23 519 (66.82) | 235 190 (66.82) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease* | 9316 (26.47) | 41 992 (11.93) |

| Heart failure | 7136 (20.28) | 17 285 (4.91) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6102 (17.34) | 26 850 (7.63) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5330 (15.14) | 27 095 (7.70) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 4910 (13.95) | 30 224 (8.59) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3914 (11.12) | 15 798 (4.49) |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy, n (%) | ||

| Beta blockers | 8569 (24.35) | 52 878 (15.02) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 6978 (19.83) | 55 877 (15.88) |

| Antithrombotics | 16 075 (45.67) | 102 020 (28.99) |

| Diuretics | 17 516 (49.77) | 107 869 (30.65) |

| Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors | 13 105 (37.24) | 89 481 (25.42) |

| Nitrates | 3962 (11.26) | 14 416 (4.10) |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs class 1 or 3 | 675 (1.92) | 1887 (0.54) |

| QT-prolonging drugs | 5857 (16.64) | 28 932 (8.22) |

Numbers are number (%) unless indicated otherwise.

*Including acute myocardial infarction.

Results

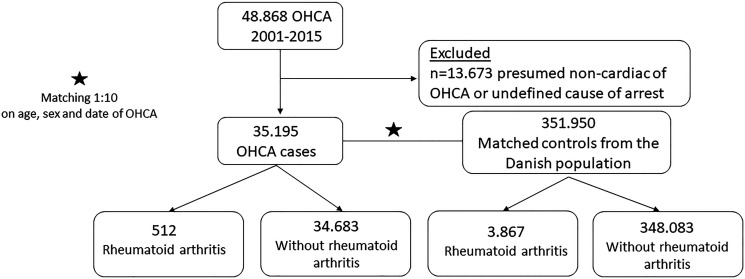

The study population consisted of 35 195 OHCA cases (median age 72 years, 66.8% men, table 1) and 351 950 matched non-OHCA controls (figure 1). Compared with non-OHCA controls, OHCA cases had generally more cardiovascular diseases, such as ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral artery disease (table 1). Also, use of cardiovascular drugs and QT-prolonging drugs was more prevalent among OHCA cases (table 1). The baseline characteristics of OHCA cases with and without RA are shown in table 2. Cardiovascular comorbidities were much more prevalent among cases with RA than cases without RA regarding ischaemic heart disease (35.35% vs 26.34%), heart failure (29.30% vs 20.14%), atrial fibrillation (20.51% vs 17.29%), cerebrovascular disease (15.43% vs 13.93%) and peripheral artery disease (16.21% vs 11.05%). Also, use of cardiovascular drugs and QT-prolonging drugs was more prevalent among cases with RA than cases without RA (table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) cases and controls.

Table 2.

Characteristics of OHCA cases with and out without rheumatoid arthritis

| Cases with rheumatoid arthritis (n=512) |

Cases without rheumatoid arthritis (n=34 683) |

|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 76 (68–82) | 72 (62–81) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 231 (45.12) | 23 288 (67.15) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease* | 181 (35.35) | 9135 (26.34) |

| Heart failure | 150 (29.30) | 6986 (20.14) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 105 (20.51) | 5997 (17.29) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 79 (15.43) | 5251 (15.14) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 79 (15.43) | 4831 (13.93) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 83 (16.21) | 3831 (11.05) |

| Concomitant pharmacotherapy, n (%) | ||

| Beta blockers | 150 (29.30) | 8419 (24.27) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 113 (22.07) | 6865 (19.79) |

| Antithrombotics | 272 (53.13) | 15 803 (45.46) |

| Diuretics | 324 (63.28) | 17 192 (49.57) |

| Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors | 218 (42.58) | 12 887 (37.16) |

| Nitrates | 65 (12.70) | 3897 (11.24) |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs class 1 or 3 | 14 (2.73) | 661 (1.91) |

| QT-prolonging drugs | 103 (20.12) | 5754 (16.59) |

Numbers are number (%) unless indicated otherwise.

*Including acute myocardial infarction.

OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

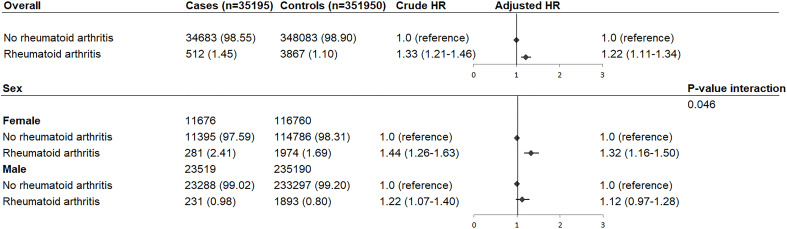

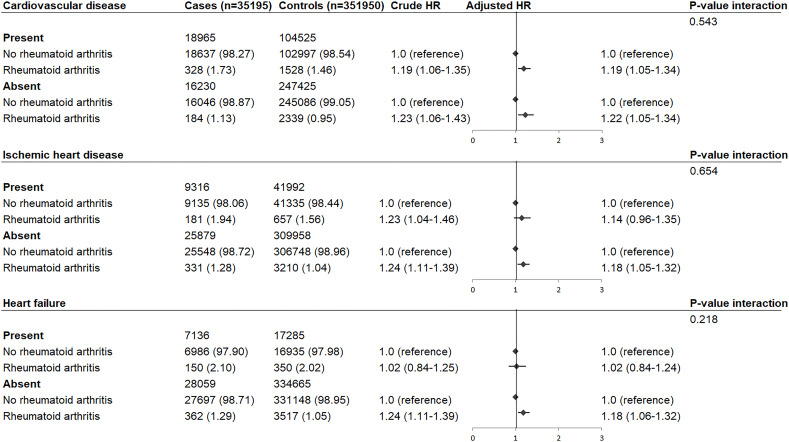

RA was diagnosed by 512 (1.45%) cases and 3867 (1.10%) controls, and was associated with increased rate of OHCA after adjustments for common OHCA risk factors (HR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.34, figure 2). Stratification according to sex revealed that this increased OHCA rate occurred in women (HR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.16 to 1.50) but not in men (HR: 1.12, 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.28; P value interaction=0.046, figure 2). Stratification according to cardiovascular disease showed that OHCA rate was not further increased in patients with cardiovascular disease (cardiovascular disease: HR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.34; no cardiovascular disease: HR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.34; P value interaction=0.543, figure 3). Also, the HR did not vary by the presence of ischaemic heart disease (ischaemic heart disease: HR: 1.14, 95% CI: 0.96 to 1.35; no ischaemic heart disease: HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.32; P value interaction=0.654, figure 3) or heart failure (heart failure: HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.84 to 1.24; no heart failure: HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.32; P value interaction=0.218, figure 3). Next, we studied the association between use of NSAIDs and OHCA among patients with RA (table 3). NSAIDs were used by 110 OHCA cases with RA (21.48%) and 873 non-OHCA controls with RA (22.58%), and were not associated with increased rate of OHCA (HR: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.82 to 1.30, table 3). Furthermore, when we studied the association between individual NSAIDs and OHCA, we found that none of the NSAIDs increased the rate of OHCA (diclofenac: HR 0.84 (95% CI: 0.43 to 1.63); ibuprofen: HR 1.06 (95% CI: 0.74 to 1.51); naproxen: HR 1.17 (95% CI: 0.44 to 3.08); celecoxib HR: 0.85 (95% CI: 0.38 to 1.90); rofecoxib: HR 1.80 (95% CI: 0.82 to 3.94)).

Figure 2.

HR of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with individuals without rheumatoid arthritis: overall and stratification according to sex. Numbers in table are number (%) unless indicated otherwise. Error bars denote 95% CI. HR adjusted for cardiovascular comorbidities and the use of QT-prolonging drugs.

Figure 3.

HR of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with individuals without rheumatoid arthritis: stratification according to cardiovascular disease, ischaemic heart disease and heart failure. Numbers in table are number (%) unless indicated otherwise. Error bars denote 95% CI. HR adjusted for age, sex, cardiovascular comorbidities and the use of QT-prolonging drugs.

Table 3.

HR of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest following treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| Cases (n=512) |

Controls (n=3867) |

Crude HR | Adjusted HR | |

| No use of NSAIDs | 402 (78.52) | 2994 (77.42) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) |

| Use of NSAIDs | 110 (21.48) | 873 (22.58) | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.17) | 1.03 (0.82 to 1.30) |

| Individual NSAID | ||||

| Diclofenac | 10 (1.95) | 99 (2.56) | 0.75 (0.39 to 1.46) | 0.84 (0.43 to 1.63) |

| Ibuprofen | 39 (7.62) | 294 (7.60) | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.39) | 1.06 (0.74 to 1.51) |

| Naproxen | 5 (0.95) | 34 (0.88) | 1.09 (0.42 to 2.81) | 1.17 (0.44 to 3.08) |

| Celecoxib | 7 (1.37) | 70 (1.81) | 0.74 (0.40 to 1.63) | 0.85 (0.38 to 1.90) |

| Rofecoxib | 8 (1.56) | 38 (0.98) | 1.53 (0.71 to 3.31) | 1.80 (0.82 to 3.94) |

| Others | 38 (7.42) | 324 (8.38) | 0.87 (0.61 to 1.23) | 0.96 (0.67 to 1.38) |

Numbers in table are number (%) unless indicated otherwise. HR adjusted for age, sex, cardiovascular comorbidities and the use of QT-prolonging drugs. Not included users of multiple NSAIDs.

Discussion

In this nationwide population-based study, we report that RA was associated with increased rate of OHCA. This increased rate occurred in women but not in men, and persisted after adjustments for common OHCA risk factors. Furthermore, there were no significant differences in OHCA rates between patients with and without cardiovascular comorbidities. Finally, use of NSAIDs in patients with RA was not associated with higher rate of OHCA.

Is RA an independent risk factor for OHCA?

We examined whether our finding was explained by differences in patient characteristics that may have resulted in differences in a priori OHCA rate between patients with RA and non-RA controls. Here, we confirmed our expectation that cases with patients with RA had more cardiovascular comorbidities than cases without non-RA controls (table 2). Although systemic inflammation is able to accelerate the development of atherosclerosis and related ischaemic consequences associated with arrhythmias and OHCA,6 the association between RA and increased OHCA rate in our study persisted after adjustment for ischaemic heart disease and heart failure. Moreover, stratification according to cardiovascular disease revealed no statistical difference in OHCA rates between patients with and without cardiovascular comorbidities. Given these observations, our data suggest that increased OHCA rate is not the result of increased prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities observed in patients with RA, but hint to the possibility that other factors with direct impact on cardiac electrophysiology may enhance the OHCA risk in patients with RA. Indeed, accumulating evidence from clinical and pathophysiological data indicates that inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα) directly affect cardiac electrophysiology by inhibiting cardiac potassium currents which largely drives cardiac repolarisation, and which may lead to QT-prolongation in patients with RA.8 9 Aromolaran et al showed that IL-6 directly inhibits cardiac potassium current Ikr, and thereby prolongs the action potential (AP) duration in ventricular myocytes.18 Wang et al demonstrated that TNFα reduced Ikr and prolonged the AP duration in a dose-dependent manner, while these effects were prevented by anti-TNF receptor antibody.19 In addition, previous studies showed that TNFα,20 IL-621 and IL-122 also prolong the AP duration by enhancing L-type calcium current (ICa, L). These findings were supported by clinical studies, where longer QT-interval duration in patients with RA compared with healthy controls was found.23 Second, QT-prolongation in RA may also occur by several autoantibodies, in particular anti-Ro antibodies, which are formed in 5%–15% of patients with RA.9 Indeed, anti-Ro antibodies impair cardiac repolarisation by inhibiting Ikr and Ito, which may lead to QT-prolongation and increase the risk of OHCA.24 Lastly, QT-prolongation may also result from dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system induced by inflammatory cytokines secondary to excessive immune-inflammatory activation.8 9 25 Cytokines may increase the sympathetic outflow, leading to an increase of epinephrine and norepinephrine that inhibits macrophage activation and suppress synthesis of TNFα and other cytokines.8 9 25 Increased sympathetic system may result in cardiac arrhythmias by afterdepolarisations and abnormal automaticity25 and increased dispersion of repolarisation.26

It has been suggested that NSAIDs were associated with increased OHCA risk,17 but this was not confirmed in another study.27 These discrepancies may have been the result of different study designs. We found no increased OHCA rate associated with the use of NSAIDs among patients with RA, ruling out the possibility that increased OHCA rate may be a result of treatment with NSAIDs.

RA is associated with increased rate of OHCA in women

The results of our study indicate that increased OHCA rate associated with RA occurred in women but not in men, fitting to the observation that women have less repolarisation reserve than men, and therefore are more prone to QT-prolongation.10 To our knowledge, this finding has not been reported previously. Because it forms the basis for a differentiated use of QT-prolonging drugs in women and men with RA, the observation is of clinical relevance.

Comparison with other studies

Our finding that RA is associated with increased OHCA rate is supported by a previous study, where it was reported that patients with RA were twice as likely to experience sudden cardiac death compared with non-RA controls after adjustment for myocardial infarction and revascularisation.5 That study, however, had limited sample size. Furthermore, data used in that study relied on inpatient and outpatient medical records, and therefore, may have omitted patients who died prior to hospital admission. Our study resolved these limitations by using a large dedicated OHCA registry in which OHCA patients who died before reaching the hospital and those who survived until hospital admission were enrolled. Furthermore, the association between RA and OHCA was not studied in women and men separately, and therefore, the overall association reported in that study may be applicable to women but not to men.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study resides in its population-based design in which large and unselected number of OHCA patients were included from complete nationwide databases, thereby minimising the risk of inclusion and selection bias. Nevertheless, our study has also some limitations. A limitation is that we lacked information on several risk factors of OHCA such as smoking and body mass index which could result in residual bias. Another limitation is that misclassification bias may occur since not all the diagnostic codes were validated. However, most of the used codes in our study have a high positive predictive value.

Conclusion

In the general population, RA is associated with increased rate of OHCA in women but not in men.

Acknowledgments

For completion of the case reports which form the Danish Cardiac Arrest Registry, the authors thank the Danish Emergency Medical Services.

Footnotes

Contributors: HH wrote the manuscript. TEE conceived the study idea, performed the analyses and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically revised and approved the manuscript. TEE is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data underlying the present article is not available to be shared publicly, as access to Danish registry raw data for research purposes must be granted individually by Danish authorities.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The present study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Agency Ref.no 2007-58-00158, local ref.no. GEH-2014-017, I-Suite.no. 02735). In Denmark, register-based studies do not require further approval.

References

- 1.Myerburg RJ, Castellanos A. Cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death. In: Libby P, Bonow RO, Mann DL, et al., eds. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Oxford, UK: Elsevier, 2007: 933–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1473–82. 10.1056/NEJMra000650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayashi M, Shimizu W, Albert CM. The spectrum of epidemiology underlying sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 2015;116:1887–906. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters MJL, Symmons DPM, McCarey D, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:325–31. 10.1136/ard.2009.113696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2005;52:402–11. 10.1002/art.20853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 2008;121:S9–14. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mantel Ängla, Holmqvist M, Jernberg T, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a more severe presentation of acute coronary syndrome and worse short-term outcome. Eur Heart J 2015;36:3413–22. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazzerini PE, Capecchi PL, Laghi-Pasini F. Systemic inflammation and arrhythmic risk: lessons from rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Heart J 2017;38:1717–27. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel KHK, Jones TN, Sattler S, et al. Proarrhythmic electrophysiological and structural remodeling in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2020;319:H1008–20. 10.1152/ajpheart.00401.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varró A, Baczkó I. Cardiac ventricular repolarization reserve: a principle for understanding drug-related proarrhythmic risk. Br J Pharmacol 2011;164:14–36. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01367.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eroglu TE, Folke F, Tan HL. Risk of out‐of‐hospital cardiac arrest in patients with epilepsy and users of antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2022. 10.1111/bcp.15313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mainz J, Hess MH, Johnsen SP. The Danish unique personal identifier and the Danish civil registration system as a tool for research and quality improvement. Int J Qual Health Care 2019;31:717–20. 10.1093/intqhc/mzz008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eroglu TE, Mohr GH, Blom MT, et al. Differential effects on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of dihydropyridines: real-world data from population-based cohorts across two European countries. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2020;6:347–55. 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvz038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish national patient registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helweg-Larsen K. The Danish register of causes of death. Scand J Public Health 2011;39:26–9. 10.1177/1403494811399958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sondergaard KB, Weeke P, Wissenberg M, et al. Non-Steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is associated with increased risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a nationwide case-time-control study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2017;3:100–7. 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aromolaran AS, Srivastava U, Alí A, et al. Interleukin-6 inhibition of hERG underlies risk for acquired long QT in cardiac and systemic inflammation. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Wang H, Zhang Y, et al. Impairment of HERG K(+) channel function by tumor necrosis factor-alpha: role of reactive oxygen species as a mediator. J Biol Chem 2004;279:13289–92. 10.1074/jbc.C400025200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.London B, Baker LC, Lee JS, et al. Calcium-dependent arrhythmias in transgenic mice with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003;284:H431–41. 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagiwara Y, Miyoshi S, Fukuda K, et al. SHP2-mediated signaling cascade through gp130 is essential for LIF-dependent ICaL, [Ca2+]i transient, and APD increase in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2007;43:710–6. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YH, Rozanski GJ. Effects of human recombinant interleukin-1 on electrical properties of guinea pig ventricular cells. Cardiovasc Res 1993;27:525–30. 10.1093/cvr/27.3.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H, Kobayashi Y, Yokoe I, et al. Heart rate–corrected QT interval duration in rheumatoid arthritis and its reduction with treatment with the interleukin 6 inhibitor tocilizumab. J Rheumatol 2018;45:1620–7. 10.3899/jrheum.180065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazzerini PE, Laghi-Pasini F, Boutjdir M, et al. Cardioimmunology of arrhythmias: the role of autoimmune and inflammatory cardiac channelopathies. Nat Rev Immunol 2019;19:63–4. 10.1038/s41577-018-0098-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herring N, Kalla M, Paterson DJ. The autonomic nervous system and cardiac arrhythmias: current concepts and emerging therapies. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:707–26. 10.1038/s41569-019-0221-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meijborg VMF, Boukens BJD, Janse MJ, et al. Stellate ganglion stimulation causes spatiotemporal changes in ventricular repolarization in pig. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:795–803. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakhriansyah M, Souverein PC, Klungel OH, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a case-control study. Europace 2019;21:99–105. 10.1093/europace/euy180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

openhrt-2022-001987supp001.pdf (39.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the present article is not available to be shared publicly, as access to Danish registry raw data for research purposes must be granted individually by Danish authorities.