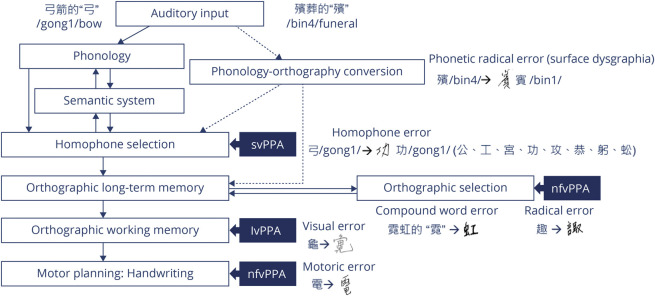

Figure 4. Cognitive Architectural Model of Orthographic Dictation in Chinese Language Users.

This is a schematic cognitive architecture model of orthographic dictation for Chinese language users with additional homophone and orthographic selection processes included. For a pictographic character such as “弓” (/gong1/bow), there are 8 other common homophones “公、工、宮、功、攻、恭、躬、蚣.” As the auditory stimuli specified that target character to be “弓箭的弓” (the character “bow” in the word “bow and arrow”), Chinese language users are thus able to select the target character. This process is critical for the homophone-rich Chinese language and reliant on semantic knowledge and lexical retrieval functions, which are impaired in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (svPPA) and logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia (lvPPA). Chinese language is also rich in compound words, with most of its characters constructed by assorted radicals. In individuals with nonfluent/agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (nfvPPA), the orthographic long-term memory impairment coupled with the inability to suppress the other frequently paired characters or to select the accurate radicals would result in compound word (e.g.,  for “霓虹的”/“霓”) or radical (e.g.,

for “霓虹的”/“霓”) or radical (e.g.,  for “趣”) writing errors. The visuospatial complexity of Chinese characters requires a higher demand for orthographic working memory and motor functions. When impaired, Chinese language users produce orthographically similar writing errors (e.g.,

for “趣”) writing errors. The visuospatial complexity of Chinese characters requires a higher demand for orthographic working memory and motor functions. When impaired, Chinese language users produce orthographically similar writing errors (e.g.,  for “龜”) or motor dysgraphia (e.g.,

for “龜”) or motor dysgraphia (e.g.,  for “電”), as noted in participants with lvPPA and participants with nfvPPA. Contrary to English language users, sublexical phonology–orthography conversion such as surface dysgraphia (e.g.,

for “電”), as noted in participants with lvPPA and participants with nfvPPA. Contrary to English language users, sublexical phonology–orthography conversion such as surface dysgraphia (e.g.,  for “殯”) is uncommon.

for “殯”) is uncommon.