Abstract

There has been increased attention on the role of indirect trauma and the need for burnout prevention for behavioral health workers. Though frontline workers traditionally serve high needs and vulnerable populations, pandemic challenges have involved service delivery pivots to meet social distancing and safety guidelines, and have resulted in staff shortages and increased caseloads, increased use of maladaptive coping skills such as substance use, and increased mental health concerns within the workforce. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma within the workforce have often been linked with increased feelings of burnout. A socio-ecological model can provide a multilevel framework for addressing burnout and increasing resiliency among frontline workers. This article discusses recommendations for preventing burnout on an individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and societal level. Prevention interventions include increasing training, mentorship, peer support, supervision, organizational culture, and interdisciplinary licensure efforts.

Introduction

There has been increased attention on the role of indirect trauma and the need for burnout prevention for behavioral health workers. Though frontline workers traditionally serve high needs and vulnerable populations, pandemic challenges have involved service delivery pivots to meet social distancing and safety guidelines, and have resulted in staff shortages and increased caseloads, increased use of maladaptive coping skills such as substance use, and increased mental health concerns within the workforce. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma within the workforce have often been linked with increased feelings of burnout.1 Some studies have predicted clinician burnout at more than 50%.2 For example, it has been found that social workers have higher levels of stress and burnout when compared to other occupational groups due to the nature of the practice and the work environment.3 Some studies have also predicted over 50% of physicians and 30% of nurses experience burnout.4 Historically, burned-out workers leave the workforce at higher rates than their colleagues experiencing compassion satisfaction. Burned-out workers frequently do not deliver high-value empathetic services which can lead to poor service quality and shortages in service availability.

Indirect Trauma

Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma are forms of indirect trauma, which occur as a result of continuous exposure to victims of trauma and violence, and typically are occupationally related.5 While both vicarious and secondary trauma leads to burnout, they can be distinguished by how they impact the worker. Vicarious traumatization represents a philosophical change in the worker’s viewpoint based on traumatic events and stories shared by clients. On the other hand, secondary traumatic stress describes the emotional and mental state of the worker after hearing about a client’s trauma experience. Frequently processing personal tragedies and trauma with clients, the chronic nature and complexity of client problems, resistant clients, and the vulnerability of the populations served are all work environment factors that increase burnout risk.1 Some workers may report intrusive negative thoughts or use defense mechanisms such as avoidance of certain clients associated with negative or traumatic situations.6 Throughout this article, the close linkages between secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, and burnout are assumed, and though distinctions exist between these terms, the impact on the workforce is similar, and the terms have been explored to inform this model.

Signs of burnout

The outcome of secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma is frequently seen through the symptoms of burnout. Burnout has been conceptualized as a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal job stressors. Signs of burnout include exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment.7 Exhaustion includes feelings of cynicism and job detachment, wearing out, loss of energy, depletion, and fatigue. Depersonalization includes negative or inappropriate attitudes towards clients, irritability, loss of idealism, and withdrawal. The third concept, reduced personal accomplishment, includes reduced productivity, low morale, and an inability to cope. Burnout symptoms result in a negative outlook towards self and others.8 The significance and impact of burnout are far-reaching as it relates to workforce retention and work-life challenges.

Case Studies

Some examples of workers experiencing burnout as an outcome of indirect trauma in the workplace include Sara and Monica. Sara is a new nurse at a methadone clinic. She is excited about her work and the population she is serving. However, Sara quickly finds that her coworkers speak negatively about their clients, and one encouraged her to show less enthusiasm about client change as he has seen minimal improvement in his caseload. Sara begins to dread going to work and finds that she has begun to have shorter interactions with her clients to avoid hearing about their triggers and setbacks in their recovery journey.

Monica has been a rural mental health therapist for nineteen years, and she has seen many policy shifts over the years. Since the beginning of the pandemic, her agency has decreased in size by forty percent due to coworker retirements and resignations. Her caseload has increased significantly, and she struggled throughout the pandemic due to her need to transition to telehealth sessions, her agency’s expectation that all therapists will maintain a full schedule from home, and supervising her son’s virtual learning during school closures. She has struggled to manage her self-care and balance her roles as a worker, a mother, and a wife. Though Monica used to greatly enjoy her job, she has begun to dread getting up to start her day, and has found herself snapping at her son and her partner. She has found herself using more sick time for her own coping and mental health and has found herself becoming more easily frustrated with her clients and co-workers.

Case Study Analysis

As demonstrated by Sara and Monica, the impact of burnout is wide-reaching due to reduced productivity and impaired work quality, increased personal conflict, and disruption of job tasks and service delivery.4 Burnout undermines the care and professional attention given to clients,9 and impacts therapeutic relationships, which can negatively impact recovery outcomes.10 Burnout has an impact on clients, the work environment, and coworkers,11 with an impact that also expands into interpersonal relationships outside of the work environment.12 There are multiple types of interventions that could be used to decrease burnout and promote resiliency in the cases of Sara and Monica. Increased training and education, a strong support system to brainstorm healthy ways to cope with workplace stress, increased community awareness of workforce burnout, advocating for opportunities for educational attainment, and the creation of consortiums designed to improve the life experiences of rural workers would assist with preventing burnout.

Socio-Ecological Model

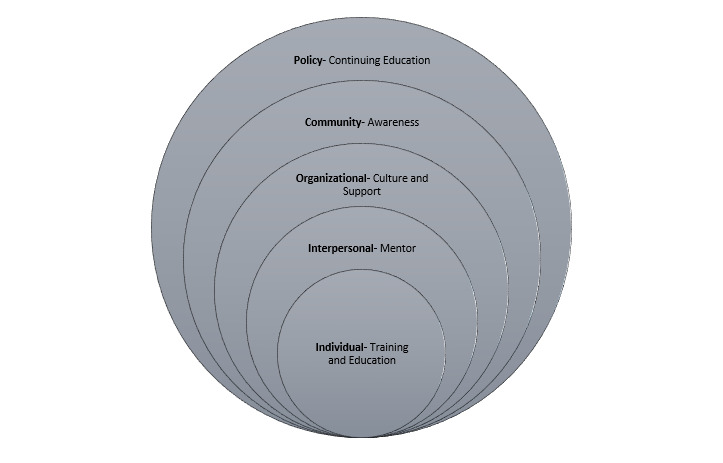

A multilevel framework can provide solutions for addressing burnout and increasing resiliency among frontline workers. Ecological models, first described by Urie Bronfenbrenner,13 assume that one’s external environment influences functioning. The ecological environment is conceived as a set of nested structures, each inside the other, in which an individual is conceptualized at the center of the interconnected systems. The social-ecological model extends the work of Bronfenbrenner to recognize levels of influence related to the well-being of one’s physical and mental health. The social-ecological model proposes that it is necessary to intervene across multiple systems to protect individuals from experiencing the impact of burnout and secondary traumatic stress.14

The Socio-ecological Model for Burnout Prevention (see Figure 1) proposes several interdependent and interactional factors, including individual, relationship, organizational, community, and societal factors, that can reduce burnout. The model is designed to identify opportunities to reduce burnout by promoting both individual and environmental factors as strategies to create a comprehensive system of support to address burnout. It addresses the importance of evidence-based interventions directed at changing individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and societal factors that can increase resiliency. The first level of the model represents biological (e.g., age and sex) and personal belief systems (e.g., self-efficacy) that influence individual actions.14 McLeroy and colleagues15 describe examples of individual-level factors as demographics, educational status, self-concept, and developmental history of the individual. This level of the social-ecological model focuses on promoting changes to attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that would increase positive personal factors to prevent burnout. Individual interventions for burnout prevention focus on areas such as training, mentorship, mindfulness practice, self-care, and achieving a work-life balance.

Figure 1.

The Social Ecological Model for Burnout Prevention

Interpersonal relationships are designed to create change within social relationships and refer to one’s close social networks, such as friends and family members, who might influence a person’s beliefs and behaviors. Burnout prevention strategies at the interpersonal level aim to build strong connections with others. The organizational or institutional level of the socio-ecological model focuses on ways in which organizations can support a culture and work environment that prevent burnout. Burnout prevention efforts at this level should emphasize strengthening education, training, and connections with the workforce that can lead to early identification of employees at high risk of burnout and compassion fatigue. The community level is designed to impact the relationship that a person has with neighborhood structures such as schools, churches, workplaces, etc.16 Improving the physical and social atmosphere of community settings includes creating positive norms and standards that promote safe and healthy community settings; empowering community groups to advocate for change; and increasing access and availability of services.14,16 The societal level refers to the cultural context in which individuals reside including socioeconomic status, values, and ethnicities of others in the surrounding environment. Societal level influences are a product of social and cultural norms that allow individuals to maintain ineffective methods for coping with stress.14 Strategies to prevent burnout at this level include efforts to strengthen financial, educational, and social policies that influence burnout.

Given that burnout is determined by several interactive factors, the socio-ecological systems theory appropriately conceptualizes how environmental factors can affect a person’s quality of life. The literature on prevention intervention strategies of each level of the socio-ecological model is discussed below to provide a comprehensive strategy for preventing burnout.

Individual Level Interventions

Training Intervention. Increased awareness of the signs and impact of burnout is an essential prevention tool for burnout in the workforce, as are regular burnout screenings.1 The Maslach Burnout Inventory was developed in 1986 and is the most utilized burnout screening instrument. This instrument could be used by an agency longitudinally to measure change in each staff person and to inform needed support interventions. Regularly scheduled burnout intervention training will normalize the burnout continuum, from compassion satisfaction to compassion fatigue, and encourage self-awareness and self-care within the workforce. A variety of trainings from the literature are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Burnout Trainings.

| Types of Trainings Reviewed |

|---|

| Acceptance and Commitment Therapy techniques • Aspects of ACT to decrease burnout in addiction counselors.10 |

| Education • Series of 3, ninety-minute education sessions focused on compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma, self-care, compassion satisfaction, quality of life, and resilience.17 |

| Mindfulness • Mindfulness Based Wellness and Resilience (MBWR)- brief mindfulness focused intervention for primary care team to promote resilience and prevent burnout of professionals, participants perceived benefits from the training.18 • Online Mind-Body Skills Training (MBST) Modules. Focused on the promotion of resilience, mindfulness, and empathy. Participants included nurses, dieticians, physicians, clinical trainees, health researchers, and social workers. Positive results were found in all three areas of focus.19 |

The training model utilized by an agency should be responsive to the workforce at that agency in logistical consideration of modality, length, duration, and frequency. The burnout training model developed by an agency should not increase the stress on the workforce in such areas as extensive time away from work, travel, vaccine hesitancy, etc. Given the current landscape of the workforce, and the increased comfort with virtual platforms, a virtual training or hybrid training model may best meet the needs of all training stakeholders. Additionally, multiple types of activities should be included within the intervention, such as:

Education on burnout,

Health promotion education and practices,

Collegial socialization,

Team building activities within work units,

Self-care planning,

Experiential practice of activities related to mindfulness

Lastly, it is essential to build on and promote existing resources. Handouts may be provided on existing free and low-cost resources such as mindfulness apps, guided imagery downloads, white noise downloads and apps, mood and stress trackers, and existing toolkits, etc.

Evaluations of the effectiveness of the training intervention should be completed, and possible variables and measurement tools may include resilience (Brief Resilience Scale), burnout (Maslach Burnout Inventory), perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale), compassion satisfaction and the effects of secondary trauma (Professional Quality of Life Scale- Version 5).

Mindfulness Practice. Positive mental health refers to a state of wellbeing without the presence of psychopathology.20 Mindfulness practice supports positive mental health through decreasing perceived stress and increasing psychological wellbeing. Mindfulness techniques can be incorporated into trainings, self-care practices, mentorship activities, supervisory practice, or adapted as a philosophical guiding principal for organizational culture.

Self-Care. Research supports that some of the best ways to mitigate burnout are increasing awareness of the signs and symptoms of burnout, creating a self-care routine,21 and maintaining a work-life balance.22 Table 2 provides details on self-care recommendations from the literature.

Table 2. Self-Care Recommendations.

| Self-Care Recommendations |

|---|

| Taking breaks, maintaining a sustainable and manageable workload, developing healthy job-related relationships, and developing healthy habits such as exercising, eating right, and getting enough sleep.7 |

| Self-awareness, balance, flexibility, physical health, social supports, spirituality, utilization of leisure time, taking breaks as needed, using time management skills, engaging in sleep hygiene techniques, maintaining a balanced diet and engaging in physical activity, and developing a strong social support system.22 |

| Create a self-care routine.21 |

| Practice self-care and increase professional supports.23 |

| Slowing down and breaking large projects into manageable tasks.24 |

Interpersonal Level Interventions

Building strong interpersonal relationships among work colleagues, supervisors, and peer relationships can improve personal well-being and assist with creating a healthier work environment.7

Mentorship. One way to buffer psychological distress is through increased positive social support and connections.25 Peer support is one important facet of burnout prevention26 and can be achieved through mentorship relationships. Mentorship is associated with lower levels of burnout for emerging professionals.27 Mentorship provides the opportunity to build on, and extend, the effects of individual training interventions. It fosters relationships and connections between mentors and mentees within, or between agencies. Support of formal mentorship relationships and activities demonstrates an organizational culture supportive of staff needs. Mentorship may include regularly scheduled meetings, social activities, avenues for virtual connections, and support of professional goals.

Peer Relationships. Positive relationships with colleagues and job engagement have been shown to mitigate burnout risk.7 Opportunities should be promoted to encourage strong peer relationships. These opportunities will vary based on the organizational setting, and types of services provided. For some organizations, peer relationships can be promoted through social opportunities with colleagues such as team building activities and staff appreciation events. Organizations should generate internal discussions with employees on valuable ways to support peer engagement.

Supervision Techniques. Supervisors need proper training to recognize the risks of job stressors. Supervision is an organizational component which follows three major factors: commanding, guiding, and controlling.28 This distinctive professional activity provides training and professional development to guide the functioning of hired staff. Supervision also involves creating aspects of understanding, interaction, expectations, and confidence in self, as well as providing restorative support to lessen tension and pressure between staff in the organization.28 To promote successful supervision outcomes within organizations, the supervisor should receive continuous training, education, and awareness. New methodologies for supervision practice can be established through opportunities for supervisor reflection on their work routine, client, and staff engagement.29 Though there are a variety of supervision models and activities, depending upon discipline, Table 3 provides an overview of social work supervision domains and suggested activities for each to support burnout prevention and decrease occupational vicarious trauma.

Table 3. Supervision Domains and Relevant Activities.

| Supervision Type and Description 30 | Activities |

|---|---|

| Administrative: Management & organizational policy | Assess for burnout, review agency policies on service delivery standards |

| Educational: Clinical, professional development & ethics | Encouraging continuing education on stress management and vicarious trauma |

| Supportive: Trust-building, nurturing & encouragement | Building professional identity and promoting self-care practices |

Organizational Level Influence

Organizations and their leaders play a significant role in preventing burnout and increasing job satisfaction among employees. Further, interventions at both the worker and administrator level should focus on preventing burnout in the workforce.31 Organizations have a responsibility to continually measure burnout risk in their staff, recruit and retain staff with protective factors against burnout, provide regular trainings to increase awareness and skills, and continually work towards creating and maintaining an agency culture that supports compassion satisfaction.

Measurement of Compassion Fatigue and Burnout. According to Kumar, regular burnout screenings can be a crucial step in raising awareness as well as offering help to affected staff.1 Kumar identified screening signal areas as affective, cognitive, behavioral, and motivational. Affective signals include irritability, oversensitivity, reduced emotional empathy with clients, and an increase in anger. Cognitive signals include cynical perceptions of clients, a pessimistic view of clients, and providing derogatory labels of clients. Behavioral signals include violent outbursts, irritability towards clients, interpersonal conflicts, social isolation, and mechanical responses to clients. Motivational signals include decreased interest and a lack of respect for clients.

Staffing and Training. Existing workplace and workload stress can lead to poor training of new staff members and agency staff not adequately prepared to handle job related stressors.32 As workers choose to leave agencies, either as a result of burnout or other reasons, the workload burden increases for those staff who remain,10 and becomes more difficult to manage.33 Workers with a high number of cases often have little opportunity to rest, recover and restore balance, all of which decrease service quality.7 Service delivery is further disrupted by insufficient recognition or reward of the existing workforce which is associated with feelings of inefficacy and devaluation.7

Organizational Culture. Attachment security is linked with lower levels of burnout and compassion fatigue, which is an important consideration for recruitment, training, and supervision.34 Communication pipelines to report concerns related to compassion fatigue or burnout are essential within the organizational setting.21 Burnout preventative measures in organizational cultures include ongoing supervisory support, encouragement of coworker relationships and support, and the promotion of self-care activities.35

Organizations fostering a culture of acceptance and support of the high levels of stress associated with the helping professions will be more supportive of their workforce, and strategies to continue to support the workforce are essential for recruitment and retention of a resilient workforce.

Community & Societal Level

The health of the frontline workforce can be improved by focusing on collaborative efforts among community groups and industries. Advocating for macro-level policy and systematic change can encourage workers from diverse fields such as medicine, nursing, psychology, social work, public health, etc. to bring burnout prevention to the forefront of national conversations regarding licensing and educational accreditation standards.

Interdisciplinary Licensing Efforts. As burnout continues to increase among members of helping professions, so does the need for community efforts to advocate for policy and community-level changes. Many professions such as social work have specific licensing requirements to maintain the standards and values of the profession. One policy change to assist with burnout prevention is the need for national licensure boards to mandate training on burnout prevention and self-care in their licensure renewal cycles.36 This idea is consistent with continuing education and professional development as a means to help workers stay current on best practices in the field. Burnout training modules should be available to all members of the frontline workforce to promote a widespread recognition of burnout prevention as an essential part of continuing education. Burnout prevention is a necessary element of educational training for the frontline workforce, which accrediting bodies should mandate into their curriculums.36 A successful advocacy campaign for the integration of burnout training at the community level should be community-centered, empowering, and involve multiple partnerships with various community groups.16

Access to Training. Current burnout trainings are particular to each discipline. However, the causes and symptoms of burnout among workers exist for many of the same reasons because compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma occur across disciplines. Rather than create burnout trainings specific to disciplines, trainings at the administrative, supervisory, and staff levels might be more appropriate to help workers recognize and respond to burnout and increase access and the availability of burnout prevention trainings. A key outcome of burnout prevention training across agencies is creating an organizational and community culture supportive of burnout prevention which can increase compassion satisfaction.

Funding. Consistent with most policy-level changes, securing funding and buy-in from community members and leaders are necessary. Raising awareness about burnout can not only help prevent and manage it,1 but also bring it to the forefront of researchers and policy-makers. Funding for burnout can create interdisciplinary opportunities for workers and those interested in facilitating burnout trainings to complete research related to burnout prevention.

Conclusion

A socio-ecological framework provides a basis for understanding the etiology of burnout and developing prevention and intervention practices for individuals, peers, organizations, communities, and society. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma have become prevalent conditions amongst professions that need to have continuous interventions and training implemented in the workplace. Both the future and the current behavioral health workforce across disciplines (e.g., medical, nursing, psychology, social work, public health) can benefit from understanding and implementation of burnout prevention strategies. While agencies have a responsibility to recruit and retain competent staff who are prepared to meet the functional requirements of their positions, organizations also have the responsibility to continue to support their staff to meet the day-to-day workplace demands, both physically and psychologically. This can be achieved through the use of a multi-level framework and include robust training, continuing education opportunities, regular supportive supervision sessions, assistance in attaining needed resources for service delivery, promotion of inter-collegial relationships in the workplace setting, and rewards for outstanding service delivery.

Dr. Habeger may be contacted at ahabeger@desu.edu.

References

- 1.Kumar, S. (2018). Preventing and managing burnout: What have we learned? Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 2(1). 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000703 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . (2017). Physician burnout. https://www.ahrq.gov/prevention/clinician/ahrq-works/burnout/index.html [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Lloyd, C., King, R., & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 11(3), 255–265. 10.1080/09638230020023642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reith, T. P. (2018, December 4). Burnout in the United States healthcare professionals: A narrative review. Cureus, 10(12), e3681. 10.7759/cureus.3681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elwood, L. S., Mott, J., Lohr, J. M., & Galovski, T. E. (2011, February). Secondary trauma symptoms in clinicians: A critical review of the construct, specificity, and implications for trauma-focused treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 25–36. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harr, C. R., Brice, T. S., Riley, K., & Moore, B. (2014). The impact of compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction on social work students. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 5(2). Retrieved from https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/676518 10.1086/676518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2016, June). Understanding the burnout experience: Recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 103–111. 10.1002/wps.20311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2, 99–113. 10.1002/job.4030020205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poghosyan, l., Aiken, L. H., Sloane, D. M. (2010). Factor structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory: An analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. Int J Nurs Stud, 46(7), 894-902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Vilardaga, R., Luoma, J. B., Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., Levin, M. E., Hildebrandt, M. J., et al. Bond, F. (2011, June). Burnout among the addiction counseling workforce: The differential roles of mindfulness and values-based processes and work-site factors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 40(4), 323–335. 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaconescu, M. (2015). Burnout, secondary trauma and compassion fatigue in social work. Revista de Asistenţa Sociala, 14(3), 57–63 http://staggsjamie.weebly.com/uploads/6/4/2/8/64285371/burnout_and_compassion_fatigue_in_social_workers.pdf

- 12.Salmond, E., Salmond, S., Ames, M., Kamienski, M., & Holly, C. (2019, May). Experiences of compassion fatigue in direct care nurses: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 17(5), 682–753. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. The American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krug, E. G., Dahlberg, L. L., Mercy, J. A., Zwi, A. B., & Lozano, R. (2002). World report on violence and health. World Health Organization, Geneva. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42495/9241545615_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLeroy, K. R., Steckler, A., & Bibeau, D. (Eds.). (1988). The social ecology of health promotion interventions. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golden, S. D., & Earp, J. A. (2012, June). Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ Behav, 39(3), 364–372. 10.1177/1090198111418634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein, C. J., Riggenbach-Hays, J. J., Sollenberger, L. M., Harney, D. M., & McGarvey, J. S. (2018, June). Quality of life and compassion satisfaction in clinicians: A pilot intervention study for reducing compassion fatigue. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 35(6), 882–888. 10.1177/1049909117740848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colgan, D. D., Christopher, M., Bowen, S., Brems, C., Hunsinger, M., Tucker, B., & Dapolonia, E. (2019, July 1). Mindfulness-based Wellness and Resilience intervention among interdisciplinary primary care teams: A mixed-methods feasibility and acceptability trial. Prim Health Care Res Dev, 20(e91), e91. 10.1017/S1463423619000173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemper, K. J., & Khirallah, M. (2015, October). Acute effects of online mind-body skills training on resilience, mindfulness, and empathy. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 20(4), 247–253. 10.1177/2156587215575816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keyes, C. L. (2005, June). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clay, R. (2020). Are you experiencing compassion fatigue? https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/compassion-fatigue#

- 22.Posluns, K., & Gall, T. L. (2020). Dear mental health practitioner, take care of yourselves: A literature review on self-care. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling, 42(1), 1–20. 10.1007/s10447-019-09382-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otto, A. K., Pietschmann, J., Appelles, L. M., Bebenek, M., Bischoff, L. L., Hildebrand, C., et al. Wollesen, B. (2020, October 6). Physical activity and health promotion for nursing staff in elderly care: A study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 10(10), e038202. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfifferling, J., & Gilley, K. (2000). Overcoming compassion fatigue. Family Practice Management, 7(4), 39–44.12385045 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benight, C. (2004). Collective efficacy following a series of natural disasters. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 17(4), 401–420. 10.1080/10615800512331328768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acker, J. (2012). Gendered organizations and intersectionality: Problems and possibilities. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, 31(3), 214–224. 10.1108/02610151211209072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perumalswami, C. R., Takenoshita, S., Tanabe, A., Kanda, R., Hiraike, H., Okinaga, H., et al. Nomura, K. (2020, June 3). Workplace resources, mentorship, and burnout in early career physician-scientists: A cross sectional study in Japan. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 178. 10.1186/s12909-020-02072-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, S., Denniston, C., Edouard, V., Palermo, C., Pope, K., Sutton, K., et al. Rees, C. (2019, June 1). Supervision training interventions in the health and human services: Realist synthesis protocol. BMJ Open, 9(5), e025777. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207201/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK207201.pdf [PubMed]

- 30.National Association of Social Workers. (n.d.). Best practice standards in social work supervision. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=GBrLbl4BuwI%3D&portalid=

- 31.Broome, K. M., Knight, D. K., Edwards, J. R., & Flynn, P. M. (2009, September). Leadership, burnout, and job satisfaction in outpatient drug-free treatment programs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37(2), 160–170. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miele, G., & Rutkowski, B. (2019, Oct). Addressing compassion fatigue in the context of service delivery [Virtual conference workshop]. The 16th Annual Integrated Care Conference, Universal City, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wacek, B. (2017). Factors which put social workers at a greater risk for burnout. https://sophia.stkate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1806&context=msw_papers

- 34.West, A. (2015). Associations among attachment style, burnout, and compassion fatigue in health and human service workers: A systematic review. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(6), 571–590. 10.1080/10911359.2014.988321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oser, C. B., Biebel, E. P., Pullen, E., & Harp, K. L. (2013, January-March). Causes, consequences, and prevention of burnout among substance abuse treatment counselors: A rural versus urban comparison. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(1), 17–27. 10.1080/02791072.2013.763558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreitzer, M. J., & Klatt, M. (2017, February). Educational innovations to foster resilience in the health professions. Medical Teacher, 39(2), 153–159. 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]