Abstract

Enterococcus cecorum was initially isolated from the intestine of poultry and is an uncommon cause of human infection. We report here what we believe to be the first case of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) with purpura fulminans due to Enterococcus cecorum in a 51-year-old man. As opposed to other enterococci, Enterococcus cecorum remains susceptible to third-generation cephalosporin which is the first line empirical antibiotic therapy for both patients with purpura fulminans and asplenic patients with sepsis. Despite adequate antibiotic therapy, evolution in the intensive care unit (ICU) was overwhelming with death occurring 10 h after ICU admission.

Keywords: Enterococcus cecorum, Purpura fulminans, Asplenia, Sepsis, ICU

Abbreviations: ICU, Intensive Care Unit; OPSI, Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection

Introduction

Enterococcus cecorum was initially isolated from the intestine of poultry and is an uncommon cause of human infection. We report here what we believe to be the first case of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) with purpura fulminans due to Enterococcus cecorum. As opposed to other enterococci, Enterococcus cecorum remains susceptible to third-generation cephalosporin which is the first line empirical antibiotic therapy for both patients with purpura fulminans and asplenic patients with sepsis. Despite adequate antibiotic therapy, evolution in the intensive care unit (ICU) was overwhelming with death occurring 10 h after ICU admission.

Case

A 51-year-old man was admitted to our ICU for acute circulatory failure with diarrhea and rigors for the past 48 h. His comorbidities included a chronic kidney disease (basal serum creatinine 120 µmol/L), a diabetes mellitus and a sarcoidosis with hepatosplenic involvement requiring a splenectomy fourteen years ago. The patient was treated with hydroxychloroquine and did not take any immunosuppressive drug. He had one dog but no other pet at home. He was vaccinated against Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis but did not take any antibiotic prophylaxis.

At ICU admission, the vital signs were as follows: central body temperature 34.4 °C, heart rate 121/min, arterial blood pressure 80/40 mmHg, respiratory rate 20/min, SpO2 99% while breathing room air. Coma Glasgow score was 15 and the patient was alert and oriented. There was no neck stiffness. Lung auscultation was irrelevant, as was the abdominal examination. There was no heart murmur. Skin examination revealed an extensive and marked non-blanching rash of the trunk, head and limbs (Fig. 1). Biological samples drawn at ICU admission revealed a severe lactic acidosis (pH 6.92, lactate 13 mmol/L), an acute-on-chronic kidney failure (serum creatinine 273 µmol/L) together with a disseminated intravascular coagulation (prothrombin time 20%, platelet count of 18 G/L, fibrinogen 1.9 g/L, D-dimer 20.000 ng/mL) and a marked biological inflammatory syndrome (leukocytes count 45.000/mm3, procalcitonine 57 ng/mL). Thoracic and abdominal CT-scan with contrast enhancement ruled out mesenteric ischemia, obstructive urinary or biliary tract infection and pneumonia. Transthoracic echocardiography did not reveal any valvular regurgitation nor vegetation. Direct examination of urinary sample was negative, as was the pneumococcal urinary antigen test.

Fig. 1.

Skin examination revealing an extensive and marked non-blanching rash of the trunk, head and limbs.

Initial management included prompt administration of empirical antibiotic therapy with high-dose of cefotaxime for a suspected pneumococcal purpura fulminans, massive fluid loading, renal replacement therapy for anuria with hyperkaliemia, invasive mechanical ventilation, hydrocortisone and vasopressor support with high-dose of norepinephrine. Despite these treatments, the patient's clinical condition rapidly deteriorated with death from refractory circulatory failure with multi-organ failure occurring 10 h after ICU admission.

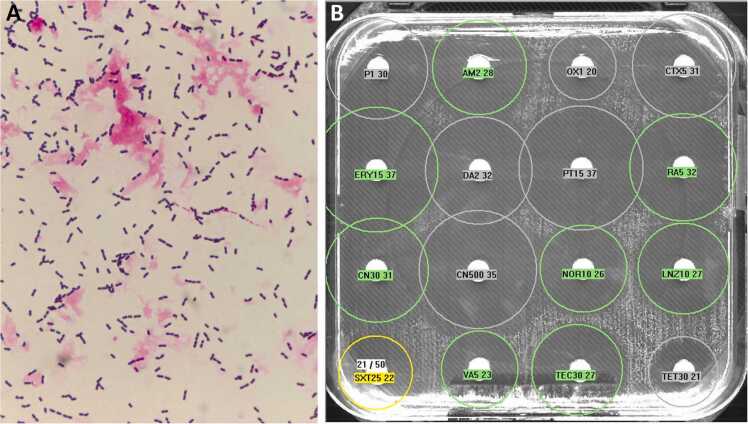

Two sets of blood cultures drawn at ICU admission (just before administration of cefotaxime) grew (both aerobic and anaerobic bottles) immotile Gram-positive cocci in chains in 9 h (Fig. 2, panel A). Identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Vitek MS - Biomerieux) yielded Enterococcus cecorum. As Enterococcus cecorum is uncommonly identified in human samples, identification was subsequently confirmed by another MALDI-TOF (Biotyper - Bruker) which confirmed the identification of Enterococcus cecorum. The strain was susceptible to ampicillin, vancomycin, linezolid and rifampicin, as shown by disk diffusion testing (Fig. 2, panel B). Importantly, Enterococcus cecorum was susceptible to third-generation cephalosporin (cefotaxime and ceftriaxone), and the third set of blood cultures drawn 6 h after the administration of cefotaxime remained sterile.

Fig. 2.

Direct examination of blood cultures revealing immotile Gram-positive diplococci (panel A) and disk diffusion testing (panel B) revealing that the strain of Enterococcus cecorum was susceptible to cefotaxime (CTX5).

Discussion

We herein report a case of purpura fulminans due to Enterococcus cecorum in an asplenic patient resulting in an overwhelming sepsis with death occurring less than 12 h after ICU admission despite prompt and effective empirical antibiotic therapy. The leading causative bacteria for purpura fulminans are Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae [1], with half of pneumococcal purpura fulminans occurring in asplenic or hyposplenic patients [2] which are well-known to be exposed to fulminant sepsis due to encapsulated bacteria [3], the so-called “overwhelming post-splenectomy infection” (OPSI). The prognosis of patients with purpura fulminans and OPSI is dismal with high ICU mortality [1], [3]. To the best of our knowledge, Enterococcus cecorum have never been reported as a causative bacterium for purpura fulminans or OPSI.

Enterococcus cecorum was first isolated in 1983 [4], taking part of the intestinal flora of many animals including chickens, pigs, horses, calves, ducks, cats, canaries and dogs [5], and is involved in poultry osteomyelitis and endocarditis [6]. Only a few cases of human infections due to Enterococcus cecorum have been reported, including aortic valve endocarditis [7], [8], thoracic empyema [9], primary bacteriemia [10], [11], peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis [12] or ascitic fluid infection in cirrhotic patient [13]. Patients with infection related to Enterococcus cecorum are commonly comorbid and/or immunocompromised [11], [14], but this bacterium have never been reported as a cause of infection in asplenic or hyposplenic patients [3]. Close contacts with animals seem to be a risk factor for contamination [7], [11]. In the present case, no poultry exposition was found but the patient was exposed to his dog which may have been the source for the transmission of Enterococcus cecorum [11], even if his relatives denied any recent bite, scratch or lick. An endogenous gastrointestinal source was also possible [9], [15].

As opposed to other enterococci which are intrinsically resistant to cephalosporins, Enterococcus cecorum remains susceptible to third-generation cephalosporin [9], [12] which is the first line empirical antibiotic therapy for both patients with purpura fulminans and asplenic patients with sepsis. Its susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins could be due to the production of penicillin-binding proteins similar to those produced by Streptococcus species rather than to those produced by other Enterococcus species [9]. Indeed, Enterococcus cecorum, historically described as Streptococcus cecorum [4], is phenotypically more closely related to Streptococcus species rather than to Enterococcus species [9], [16].

Our report highlights that Enterococcus cecorum can be a cause of purpura fulminans and overwhelming post-splenectomy infection. As opposed to other enterococcus species, this bacterium remains susceptible to third-generation cephalosporins, which is the first line empirical antibiotic therapy for both patients with purpura fulminans and asplenic patients with sepsis.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s relatives for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

References

- 1.Contou D., Sonneville R., Canoui-Poitrine F., Colin G., Coudroy R., Pène F., et al. Clinical spectrum and short-term outcome of adult patients with purpura fulminans: a French multicenter retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44:1502–1511. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Contou D., Coudroy R., Colin G., Tadié J.-M., Cour M., Sonneville R., et al. Pneumococcal purpura fulminans in asplenic or hyposplenic patients: a French multicenter exposed-unexposed retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2020;24:68. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2769-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theilacker C., Ludewig K., Serr A., Schimpf J., Held J., Bögelein M., et al. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:871–878. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devriese L.A., Dutta G.N., Farrow J.A.E., De Kerckhove V.A.N., Phillips Bay A. Streptococcus cecorum, a new species isolated from chickens. Int J Syst Evolut Microbiol N D. 1983;33:772–776. doi: 10.1099/00207713-33-4-772. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devriese L. a, Ceyssens K., Haesebrouck F. Characteristics of Enterococcus cecorum strains from the intestines of different animal species. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1991;12:137–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.1991.tb00524.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood A.M., MacKenzie G., McGiliveray N.C., Brown L., Devriese L.A., Baele M. Isolation of Enterococcus cecorum from bone lesions in broiler chickens. Vet Rec. 2002;150:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed F.Z., Baig M.W., Gascoyne-Binzi D., Sandoe J.A.T. Enterococcus cecorum aortic valve endocarditis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70:525–527. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu H., Seah V., Marriott D., Moore J. Enterococcus cecorum infective endocarditis in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia and cirrhosis. Pathology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2021.07.004. S0031-3025(21)00461-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo P.C.Y., Tam D.M.W., Lau S.K.P., Fung A.M.Y., Yuen K.-Y. Enterococcus cecorum empyema thoracis successfully treated with cefotaxime. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:919–922. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.919-922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lake A., Fields R., Guerrero F., Almuzaini Y., Sundaresh K., Staffetti J. Case of Enterococcus cecorum human bacteremia, United States. HCA Healthc J Med. 2020:1. doi: 10.36518/2689-0216.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greub G., Devriese L.A., Pot B., Dominguez J., Bille J. Enterococcus cecorum septicemia in a malnourished adult patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;16:594–598. doi: 10.1007/BF02447923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Baere T., Claeys G., Verschraegen G., Devriese L.A., Baele M., Van Vlem B., et al. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis peritonitis due to Enterococcus cecorum. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3511–3512. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.9.3511-3512.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsueh P.R., Teng L.J., Chen Y.C., Yang P.C., Ho S.W., Luh K.T. Recurrent bacteremic peritonitis caused by Enterococcus cecorum in a patient with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2450–2452. doi: 10.1128/JCM.38.6.2450-2452.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaunay E., Abat C., Rolain J.-M. Enterococcus cecorum human infection, France. New Microbes New Infect. 2015;7:50–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warnke P., Köller T., Stoll P., Podbielski A. Nosocomial infection due to Enterococcus cecorum identified by MALDI-TOF MS and Vitek 2 from a blood culture of a septic patient. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 2015;5:177–179. doi: 10.1556/1886.2015.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reuter G. Culture media for enterococci and group D-streptococci. Int J Food Microbiol. 1992;17:101–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(92)90109-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]