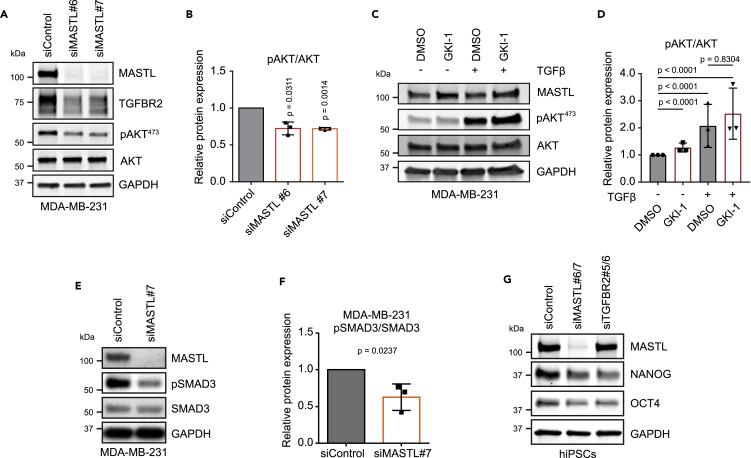

Figure 6.

MASTL controls AKT and SMAD3 activation via TGFBR2

(A) Western blotting of MASTL, TGFBR2, pAKT (Ser473), AKT, and GAPDH in siControl-, siMASTL#6-, and siMASTL#7-treated MDA-MB-231 cells after 48 h of silencing. Cells were stimulated with TGF-β (20 ng/mL) for 45 min immediately before collection.

(B) pAKT (Ser473) protein levels relative to total AKT, experimental setup shown in A. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments, one sample t-test, mean ± SD).

(C) Western blotting of MASTL, pAKT (Ser473), AKT, and GAPDH in DMSO- and GKI-1 (20μM)-treated (48 h) MDA-MB-231 cells with and without TGF-β stimulation (20 ng/mL, 45min).

(D) pAKT (Ser473) protein levels relative to total AKT, experimental setup shown in (C). (n = 3 biologically independent experiments, t-test with Welch’s correction, mean ± SD).

(E) Western blotting of MASTL, pSMAD3, SMAD3, and GAPDH in siControl- and siMASTL#7-treated MDA-MB-231 cells after 48 h. Cells were TGF-β stimulated 10 ng/mL 24 h before collection.

(F) pSMAD3 protein levels relative to total SMAD3, experimental setup shown in E. (n = 3 biologically independent experiments, unpaired t-test, mean ± SD).

(G) Western blotting of MASTL, NANOG, OCT4, and GAPDH in siControl-, siMASTL#6/7-, and siTGFBR2#5/6-treated hiPSCs after 48 h.