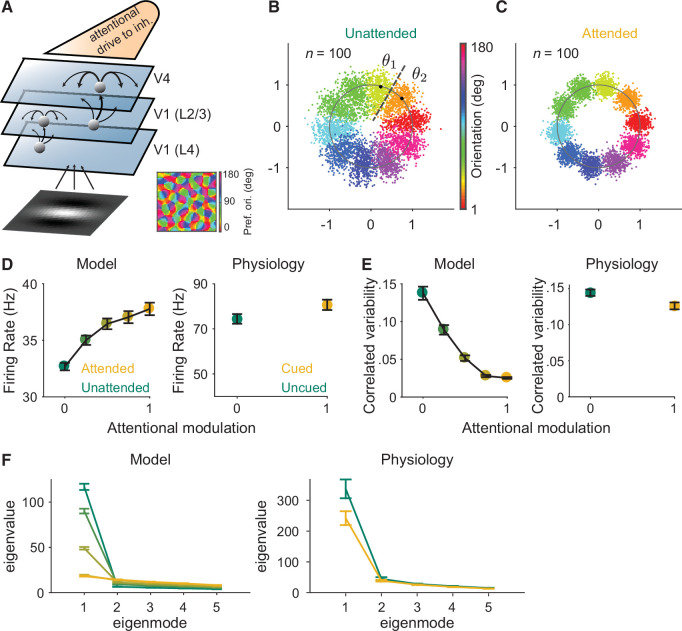

Figure 2. Mechanistic circuit model of attention effects.

(A) Schematic of an excitatory and inhibitory neuronal network model of attention (Huang et al., 2019) that extends the three-layer, spatially ordered network to include the orientation tuning and organization of V1. The network models the hierarchical connectivity between layer 4 of V1, layers 2 and 3 of V1, and V4. In this model, attention depolarizes the inhibitory neurons in V4 and increases the feedforward projection strength from layers 2 and 3 of V1 to V4. (B, C) We mapped the n-dimensional neuronal activity of our model to a two-dimensional space (a ring). Each dot represents the neuronal activity of the simulated population on a single trial and each color represents the trials for a given orientation. These fluctuations are more elongated in the (B) unattended state than in the (C) attended state. We then calculated the effects of these attentional changes on the performance of specific and general decoders (see Materials and methods). The axes are arbitrary units. (D–F) Comparisons of the modeled versus electrophysiologically recorded effects of attention on V4 population activity. (D) Firing rates of excitatory neurons increased, (E) mean correlated variability decreased, and (F) as illustrated with the first five largest eigenvalues of the shared component of the spike count covariance matrix from the V4 neurons, attention largely reduced the eigenvalue of the first mode. Attentional state denoted by marker color for the model (yellow: most attended; green: least attended) and electrophysiological data (yellow: cued; green: uncued). For the model: 30 samplings of n=50 neurons. Monkey 1 data illustrated for the electrophysiological data: n=46 days of recorded data. SEM error bars. Also see Figure 2—figure supplement 1.