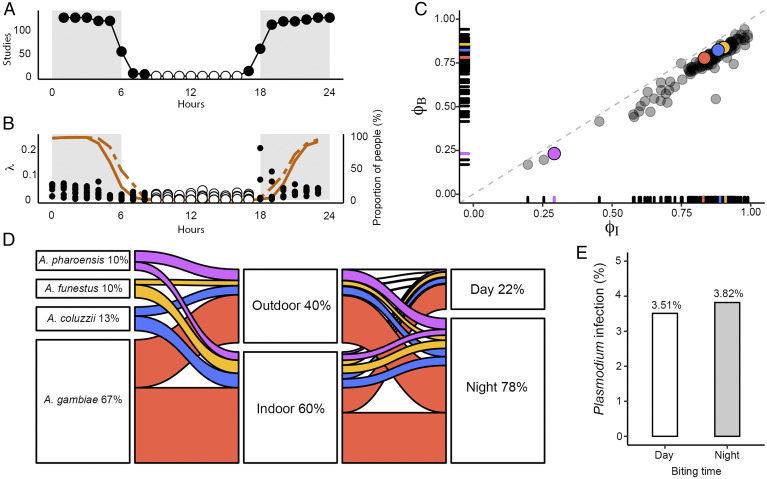

Fig. 3.

Impact of diurnal biting activity on residual malaria transmission in Bangui. (A) Sampling coverage of the studies reviewed by Sherrard-Smith et al. (24) denoted by the hour-by-hour frequency of recorded biting activity. Gray areas represent nighttime. None of the reviewed studies cover the period from 0900 to 1700 hours (white dots). (B) Hourly distribution along the day of the proportion of mosquitoes’ bites (λ, dots in the figure) in relation to the average proportion of people indoors (orange dashed line) or in bed (orange continuous line). White dots designate the period when biting occurs when people are not in households. (C) Combined mosquito and human activity data estimating mosquito biting risk expressed by the mean proportion of bites (black dots in B) taken while humans are indoors (ΦI) or in bed (ΦB). A. gambiae (red), A. coluzzii (blue), A. funestus (yellow), and A. pharoensis (violet). Each gray dot represents the corresponding values of individual studies of the systematic review (24). (D) Summary of the observed proportion of mosquito bites by species according to location and period of the day: A. gambiae (red), A. coluzzii (blue), A. funestus (yellow), and A. pharoensis (violet). (E) Prevalence of P. falciparum DNA in the head/thorax of a subset of Anopheles specimens (n = 271) randomly chosen from the dataset according to the period of the day when they were collected.