Abstract

Background

Many states, local authorities, organizations, and individuals have taken action to reduce the spread of COVID-19, particularly focused on restricting social interactions. Such actions have raised controversy regarding their implications for the spread of COVID-19 versus mental health.

Methods

We examined correlates of: (1) COVID symptoms and test results (i.e., no symptoms/tested negative, symptoms but not tested, tested positive), and (2) mental health symptoms (depressive/anxiety symptoms, COVID-related stress). Data were drawn from Fall 2020 surveys of young adults (n = 2576; Mage = 24.67; 55.8% female; 31.0% sexual minority; 5.4% Black; 12.7% Asian; 11.1% Hispanic) in six metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) with distinct COVID-related state orders. Correlates of interest included MSA, social distancing behaviors, employment status/nature, household composition, and political orientation.

Results

Overall, 3.0% tested positive for COVID-19; 7.0% had symptoms but no test; 29.1% reported at least moderate depressive/anxiety symptoms on the PHQ-4 Questionnaire. Correlates of testing positive (vs. having no symptoms) included residing in Oklahoma City vs. Boston, San Diego, or Seattle and less social distancing adherence; there were few differences between those without symptoms/negative test and those with symptoms but not tested. Correlates of greater depressive/anxiety symptoms included greater social distancing adherence, being unemployed/laid off (vs. working outside of the home), living with others (other than partners/children), and being Democrat but not Republican (vs. no lean); findings related to COVID-specific stress were similar.

Conclusion

Despite curbing the pandemic, social distancing and individual (e.g., political) and environmental factors that restrict social interaction have negative implications for mental health.

Keywords: COVID-19, Young adults, Restriction adherence, Mental health

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, COVID-19 was characterized as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (Cucinotta and Vanelli 2020). Since this time, numerous restrictions have been implemented to protect public health. In particular, social distancing measures have been a key population-level intervention to reduce the spread of COVID-19 (Courtemanche et al. 2020). There has been variability across the USA in terms of how states and local jurisdictions have intervened during the pandemic (National Academy for State Health Policy 2021). Some states and local jurisdictions implemented aggressive stay-at-home and business closure orders; at the other end of the continuum, some states preempted local jurisdictions from instituting any such orders, thus undermining effects of such restrictions across the broader US population (American Constitution Society 2020; Korevaar et al. 2020).

While the benefits of social distancing and related state orders have been documented, these restrictions have also coincided with negative outcomes (e.g., economic impact, mental health). Particularly relevant to this paper, literature has mounted regarding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions on mental health (Chiesa et al. 2021), specifically increases in symptoms of anxiety and depression (Dhaheri et al. 2021; Theis et al. 2021). However, these restrictions have not occurred in isolation. COVID-19 entailed a wide range of societal implications, including job loss, changes in how people engage in their work environment (e.g., virtually), and the nature of their social interactions with those outside of the home – all of which are related to potential exposure to COVID-19 as well as mental health outcomes (Ammar et al. 2020; Chiesa et al. 2021). Unfortunately, among the groups impacted most is the young adult population; globally, younger age groups have reported more adverse psychological consequences relative to older age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., perceived stress, loneliness, sleep, and ability to cope with stress) (Varma et al. 2021).

Identifying factors associated with both COVID-related outcomes (e.g., symptoms, testing) and mental health outcomes is critical in informing public health efforts aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19 while minimizing any undue mental health burdens. For example, risk for COVID-19 infection is in part due to nonadherence to CDC recommendations (e.g., wearing masks, observing social distancing guidelines), which has been associated with being male, not having children, higher levels of past risk-taking behavior (e.g., substance use), and lower perceived risk of COVID-19 (Pollak et al. 2020). Moreover, in the USA, there were prominent differences in COVID-19 related perspectives across groups with different political orientation; compared to Democrats, Republicans have perceived COVID-19 related risks to be less severe and social distancing to be less important – and have behaved accordingly (Allcott et al. 2020).

Despite what is known about the societal implications (e.g., disease spread, mental health) of the COVID-19 pandemic and related restrictions, there are notable limitations to the literature. Although previous research has documented important associations among a range of sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, occupation, and COVID-related and mental health outcomes (Allcott et al. 2020; Pollak et al. 2020), little research has examined a broad range of risk/protective factors and their differential associations with COVID-related outcomes and mental health. Relatedly, while there have been studies conducted on COVID-related outcomes and mental health outcomes (Ammar et al. 2020; Chiesa et al. 2021; Dhaheri et al. 2021; Theis et al. 2021; Varma et al. 2021), there has been limited examination of these COVID-related impacts in this population. Thus, research is needed to address these limitations, as such evidence has ongoing policy and public health implications.

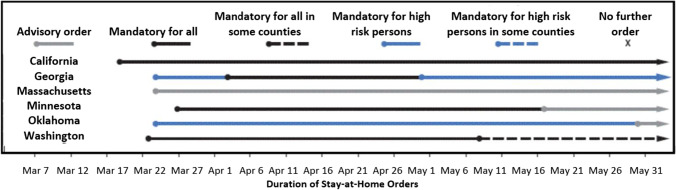

Thus, the current study examined correlates of: (1) COVID-related outcomes (e.g., not having symptoms, having symptoms but no test, testing positive); and (2) self-reported mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive/anxiety symptoms, COVID-related stress) in a sample of US young adults from six US metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in different states with varying levels of COVID-related restrictiveness (Fig. 1) (Moreland et al. 2020). We explored a broad range of potential correlates, including: residence (i.e., MSA), adherence to social distancing recommendations (as well as sanitary recommendations), employment status and nature of employment, household composition, and political orientation. We hypothesized that more restrictive COVID-19 social distancing policies, engaging in social distancing both voluntarily and involuntarily (e.g., job loss), and political orientation (i.e., being Democrat) would be associated with better COVID-19 related symptom/diagnosis outcomes but more adverse mental health outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Type and duration of COVID-19 state stay-at-home orders in the six states, March 1–May 31, 2020

Methods

Study design

We analyzed Fall 2020 survey data among young adults (aged 18–34) participating in a 2-year, 5-wave longitudinal cohort study, the Vape shop Advertising, Place characteristics and Effects Surveillance (VAPES) study that launched in Fall 2018. VAPES examines the vape retail environment and its impact on e-cigarette use, drawing participants from six metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs: Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle) with varied tobacco and marijuana legislative contexts, as well as state orders related to COVID-19 (Fig. 1) (Public Health Law Center 2020; Moreland et al. 2020). This study was approved by the [Site Blinded] Institutional Review Board.

Participants & recruitment

Participants were recruited via social media. Eligibility criteria were: (1) 18–34 years old; (2) residing in one of the six aforementioned MSAs; and (3) English speaking. Purposive, quota-based sampling was used to ensure sufficient proportions of the sample representing e-cigarette and cigarette users and to obtain roughly equal numbers of men and women and 40% racial/ethnic minority. Ads posted on Facebook and Reddit targeted individuals: (1) using indicators reflecting those within the eligible age range and geographical locations (within 15 miles of their respective MSAs); (2) by identifying work groups or activities of interest that appeal to young adults (e.g., entertainment, lifestyle, technology), as well as tobacco-related interests (e.g., Marlboro, Juul); and (3) by posting advertisements including images of young adults of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds.

After clicking an ad, potential participants were directed to a webpage that included the consent form. After consenting, they completed the eligibility screener, which included questions regarding sex, race, ethnicity, and past 30-day use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes that were used to facilitate reaching recruitment targets of subgroups in each MSA (i.e., limiting participation among specific subgroups once their target enrollment was reached). Eligible individuals were then routed to complete the Wave 1 survey (administered via Alchemer). Upon survey completion, participants were notified that, 7 days after completing the baseline survey, they would be asked to confirm their participation by clicking a “confirm” button included in an email sent to them. After confirming their participation, they were officially enrolled and emailed their first incentive ($10 Amazon e-gift card).

The duration of the recruitment period ranged from 87 to 104 days across the six MSAs. Of the 10,433 Facebook and Reddit users who clicked on ads, 9847 consented, of which 2751 (27.9%) were not allowed to advance because they were either: (a) ineligible (n = 1472) and/or (b) excluded in order to reach subgroup target enrollment (n = 1279). Of those allowed to advance to the survey, the proportion of completers was 48.8% (n = 3460/7096), of which 3006 (86.9%) confirmed participation at the 7-day follow-up). Partial completers (51.2%, n = 3636/7096) were deemed ineligible; the majority of partial completers (n = 2469, 67.9%) completed only the initial sociodemographic section of the survey (see previous work for complete participant flowchart) (Berg et al. 2021). This study uses data from Wave 1 (n = 3006; Fall 2018) and Wave 5 (n = 2476; Fall 2020; 82.4% retention; incentive of $30 Amazon e-gift card).

Measures

Outcome variables

COVID-related symptoms, testing, and diagnosis was assessed at W5 by asking, “What was your experience with testing for COVID-19? (a) I didn’t have symptoms and didn’t try to get tested; (b) I had symptoms but didn’t try to get tested; (c) I tried but could not get tested; (d) My test result was negative; (e) My test result was positive, but I was not hospitalized; (f) My test result was positive, and I was hospitalized; (g) Other; and (h) Prefer not to answer.” These items were then grouped to reflect: (1) no symptoms or tested negative (items a and d); (2) symptoms but not tested (items b and c); and (3) tested positive for COVID-19 (items e and f). “Other” (n = 6) and “prefer not to answer” (n = 38) responses were treated as missing.

Two mental health outcomes were assessed at W5 – one using a standard measure of mental health symptoms and one specifically related to COVID-related stress. The Patient Health Questionnaire – 4 item (PHQ-4) was used to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms (Kroenke et al. 2009). The PHQ-4 asks participants to report on their symptoms (e.g., “Little interest or pleasure in doing things,” “Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge”) in the past 2 weeks (0=“not at all” to 3=“nearly every day”; sum score range 0–12; Cronbach’s alpha = .90). COVID-related stress was assessed by asking, “Compared to before COVID-19, are you doing more or less of the following: (a) Feeling down or depressed; (b) Feeling anxious or stressed out; and (c) Having conflict in your home (with your partner, family, children, roommates, etc.) Response options included: -2=“much less”, -1=“somewhat less”, 0=“no different”, 1=“somewhat more”, 2=“much more”, 77=“not applicable”, and 99=“prefer not to answer”. “Not applicable” responses (n range = 38–226) were recoded to no different, and “prefer not to answer” responses (n range = 11–14) were coded as missing. Mean scores were computed with higher scores indicating greater COVID-related stress (Cronbach’s alpha = .65).

Primary correlates of interest

MSA of residence was assessed at W5 (Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, Seattle, other [treated as missing due to moving since W1]); Fig. 1 provides information regarding state-mandated stay-at-home orders March–May 2020; because Oklahoma had the least restrictive orders, Oklahoma was designated the referent group in multivariable regression analyses. Recommendation adherence was assessed at W5 by asking, “In the past 7 days, how often were you able to regularly follow these recommendations? (a) When you are outside of your home, keeping 6 feet away from people who you do not live with; (b) Avoiding having friends or others over to your home; (c) Avoiding going to other people’s homes; (d) Staying home other than to go and get food or medicine; (e) Washing your hands several times every day; (f) Avoiding touching your eyes, nose, and mouth; and (g) Wearing protective masks over your nose and mouth.” Response options were: 0=“never”, 1=“rarely”, 2=“sometimes”, 3=“often”, 4=“very often”, and 5=“always”. Social distancing adherence was operationalized as an average of responses on items a–d, with higher scores indicating greater adherence (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81); similarly, sanitary adherence was operationalized as an average of responses on items e–g (Cronbach’s alpha=0.69).

W5 employment status was assessed by asking, “What impact has COVID had on your employment? (a) not working before/during; (b) still work outside of the home (referent); (c) was working outside of home and now work from home; (d) still work from home; (e) laid off; (f) new employment as a result of COVID; or (g) other. W5 household composition was assessed by asking, “Who is in your household currently? “live with partner/spouse,” “live with children,” and “live with others” (not partner or children). At Wave 5, participants were asked how they identify politically (1=“strong Democrat” to 7=“strong Republican”); responses were then categorized into Democrat, no lean (referent group), and Republican.

Sociodemographic covariates

At Wave 1, participants were asked to report their age, gender, sexual orientation, race, and ethnicity.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were analyzed to characterize the sample. Then, bivariate analyses (i.e., ANOVAs, t-tests, Pearson correlations, Chi-square tests) were conducted to examine associations among independent variables and outcomes. Next, multivariable regressions were conducted, specifically: (a) a multinomial logistic regression identifying factors associated with having symptoms but not being tested and testing positive for COVID-19 relative to no symptoms/negative test (referent group); and (b) two linear regressions examining factors related to PHQ-4 scores (i.e., mental health symptoms) and COVID-related stress scores. Each model included the predictors of interest and sociodemographic covariates. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 with a-priori alpha set at .05.

Results

Participant characteristics

In this sample of 2453 young adults, the average age was 24.67 (SD = 4.69), and participants were 55.8% female, 31.0% sexual minority, 5.4% Black, 12.7% Asian, and 11.1% Hispanic (Table 1). With regard to primary outcomes, 3.0% tested positive for COVID-19, and 7.0% had symptoms but did not get tested. The average PHQ-4 score was 4.02 (SD = 3.35; range 0 to 12); 29.1% reported at least moderate depressive/anxiety symptoms (i.e., ≥6). The average COVID-related stress score was 0.76 (SD = 0.74; range: -2 to 2).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and bivariate associations with COVID-19 related physical health (N = 2409) and mental health outcomes at W5 (N = 2453 PHQ-4, N = 2446 COVID-related stress)

| Variables | COVID symptoms and test results | Mental health outcomes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=2453 a | No symptoms/ negative test N=2157 |

Symptoms but no test* N=179 |

Tested positive N=73 |

PHQ-4 | COVID-related stress | ||||

| N (%) or M (SD) |

N (%) or M (SD) |

N (%) or M (SD) |

N (%) or M (SD) |

p | M (SD) or r |

p | M (SD) or r |

p | |

| Sociodemographics | |||||||||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.67 (4.69) | 24.68 (4.72) | 24.82 (4.36) | 23.70 (4.28) | .188 | -.049 | .015 | -.009 | .656 |

| Gender, N (%) | .201 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| Male | 1015 (41.4) | 881 (40.8) | 76 (42.5) | 39 (53.4) | 3.46 (3.27) | .64 (.72) | |||

| Female | 1369 (55.8) | 1217 (56.4) | 97 (54.2) | 31 (42.5) | 4.34 (3.33) | .84 (.73) | |||

| Other | 69 (2.8) | 59 (2.7) | 6 (3.4) | 3 (4.1) | 6.12 (3.22) | .89 (.80) | |||

| Sexual minority, N (%) | 761 (31.0) | 661 (30.6) | 67 (37.4) | 18 (24.7) | .084 | 5.18 (3.35) | <.001 | .87 (.75) | <.001 |

| Heterosexual | 1692 (69.0) | 1496 (69.4) | 112 (62.6) | 55 (75.3) | 3.50 (3.21) | .71 (.73) | |||

| Race, N (%) | .201 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| White | 1748 (71.3) | 1532 (71.0) | 139 (77.7) | 51 (69.9) | 4.18 (3.35) | .78 (.71) | |||

| Black | 133 (5.4) | 117 (5.4) | 6 (3.4) | 4 (5.5) | 3.27 (3.05) | .49 (.97) | |||

| Asian | 312 (12.7) | 283 (13.1) | 12 (6.7) | 9 (12.3) | 3.26 (3.08) | .76 (.66) | |||

| Other | 260 (10.6) | 225 (10.4) | 22 (12.3) | 9 (12.3) | 4.23 (3.58) | .77 (.82) | |||

| Hispanic, N (%) | 272 (11.1) | 247 (11.5) | 15 (8.4) | 6 (8.2) | .330 | 3.92 (3.31) | .589 | .78 (.77) | .573 |

| No | 2181 (88.9) | 1910 (88.5) | 164 (91.6) | 67 (91.8) | 4.04 (3.35) | .76 (.73) | |||

| Predictors of interest | |||||||||

| MSA, N (%) a | <.001 | .001 | .001 | ||||||

| Atlanta | 447 (18.2) | 392 (19.7) | 27 (17.1) | 22 (33.8) | 3.62 (3.29) | .66 (.74) | |||

| Boston | 443 (18.1) | 386 (19.4) | 43 (27.2) | 5 (7.7) | 3.97 (3.31) | .76 (.75) | |||

| Minneapolis | 395 (16.1) | 340 (17.1) | 31 (19.6) | 14 (21.5) | 4.41 (3.40) | .84 (.67) | |||

| Oklahoma City | 231 (9.4) | 198 (9.9) | 15 (9.5) | 15 (23.1) | 3.97 (3.47) | .65 (.81) | |||

| San Diego | 384 (15.7) | 354 (17.8) | 19 (12.0) | 4 (6.2) | 3.70 (3.23) | .82 (.69) | |||

| Seattle | 355 (14.5) | 321 (16.1) | 23 (14.6) | 5 (7.7) | 4.46 (3.29) | .80 (.72) | |||

| Social distancing adherence, M (SD) | 3.46 (1.12) | 3.48 (1.10) | 3.45 (1.15) | 2.84 (1.34) | <.001 | .101 | <.001 | .147 | <.001 |

| Sanitary adherence, M (SD) | 3.88 (.95) | 3.90 (.94) | 3.86 (.89) | 3.66 (1.08) | .087 | .042 | .037 | .160 | <.001 |

| Employment status, N (%) | .378 | .085 | .165 | ||||||

| Unemployed (consistent) | 384 (15.7) | 336 (19.7) | 26 (19.4) | 10 (17.9) | 4.25 (3.78) | .73 (.83) | |||

| Work from home (consistent) | 149 (6.1) | 125 (7.3) | 14 (10.4) | 6 (10.7) | 3.85 (3.49) | .74 (.80) | |||

| Work outside of home (consistent) | 680 (27.7) | 606 (35.6) | 39 (29.1) | 24 (42.9) | 3.75 (3.28) | .68 (.72) | |||

| Changed to working from home | 715 (29.1) | 635 (37.3) | 55 (41.0) | 16 (28.6) | 3.77 (2.98) | .77 (.65) | |||

| Laid off | 292 (11.9) | 258 (12.0) | 20 (11.2) | 10 (13.7) | 4.75 (3.55) | .91 (.80) | |||

| New employment | 114 (4.6) | 99 (4.6) | 10 (5.6) | 2 (2.7) | 4.35 (3.34) | .88 (.73) | |||

| Other | 103 (4.2) | 86 (4.0) | 11 (6.1) | 5 (6.8) | 4.39 (3.30) | .76 (.72) | |||

| Household composition, N (%) ** | |||||||||

| Partner/spouse | 1041 (42.4) | 918 (42.6) | 69 (38.5) | 35 (47.9) | .363 | 4.05 (3.35) | .736 | .78 (.75) | .255 |

| Children | 355 (14.5) | 320 (14.8) | 20 (11.2) | 8 (11.0) | .282 | 3.48 (3.30) | .001 | .76 (.75) | .926 |

| Others (other than partner/children) | 1200 (48.9) | 1060 (49.1) | 81 (45.3) | 34 (46.6) | .563 | 4.16 (3.39) | .040 | .77 (.74) | .628 |

| No one else | 367 (15.0) | 316 (14.6) | 36 (20.1) | 12 (16.4) | .139 | 3.91 (3.24) | .486 | .69 (.70) | .058 |

| Political orientation, N (%) | .036 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||

| Republican | 305 (12.4) | 267 (12.4) | 16 (8.9) | 16 (21.9) | 2.61 (2.75) | .54 (.74) | |||

| Democrat | 1800 (73.4) | 1583 (73.4) | 143 (79.9) | 46 (63.0) | 4.36 (3.34) | .82 (.71) | |||

| No lean | 348 (14.2) | 307 (14.2) | 20 (11.2) | 11 (15.1) | 3.51 (3.45) | .61 (.81) | |||

Race categories represent individuals identifying as both Hispanic and non-Hispanic. MSA, Metropolitan statistical area.

* Symptoms but no test: did not try to or could not get tested. ** Partner/spouse, Children, and Others (other than partner/children) are not discrete categories.

a 198 participants resided in “other” MSA at W5 and were excluded from analyses

Regarding primary correlates of interest (Table 1), 19.8% resided in Atlanta, 19.6% in Boston, 17.5% in Minneapolis, 10.2% in Oklahoma City, 17.0% in San Diego, and 15.7% in Seattle. Participants reported relatively often adherence to social distancing and sanitation recommendations (M = 3.46 and M = 3.88, respectively). In terms of employment, 15.7% of participants were unemployed, 6.1% worked from home before the pandemic and continued working from home, 27.7% worked outside of the home before the pandemic and continued working outside of the home, 29.1% switched to working from home since the pandemic began, 11.9% were laid off, and 4.6% found new employment. Regarding household composition, 42.4% reported living with a romantic partner or spouse, 14.5% were living with children, and 48.9% were living with others who were not a romantic partner or children (roommates, etc.). Lastly, 12.4% identified as Republican, 73.4% as Democrat, and 14.2% reported no lean in either direction.

COVID-19 symptoms & diagnosis

In bivariate analyses (Table 1), differences in COVID-related symptoms and diagnosis existed across MSAs (p < .001; e.g., participants living in Atlanta and Oklahoma City were the most likely to test positive). Additionally, testing positive (relative to not having symptoms or not being tested) was associated with low social distancing adherence (p <. 001) and being Republican (p = .036). Multinomial logistic regression (Table 2) indicated that, relative to those reporting no symptoms/negative test (referent group), those reporting symptoms but not being tested were more likely to report “other” employment status (p = .047), as well as identify as White vs. Asian (p = .008). In addition, compared to reporting no symptoms/negative test, testing positive for COVID-19 was associated with living in Oklahoma City vs. Boston, San Diego, or Seattle (p <.003) and lower adherence to social distancing (p =. 009), as well as being male (p = .045).

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression identifying correlates of COVID symptoms and testing outcomes (ref=no symptoms/negative test)

| Variable | Symptoms but no test | Tested positive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age | 1.02 | .98, 1.06 | .409 | .96 | .89, 1.02 | .198 |

| Female (ref: male) a | .80 | .56, 1.12 | .194 | .58 | .34, .99 | .045 |

| Sexual minority (ref: heterosexual) | 1.14 | .79, 1.64 | .486 | .87 | .45, 1.66 | .666 |

| Race (ref: White) | ||||||

| Black | .64 | .27, 1.54 | .317 | 1.38 | .45, 4.22 | .574 |

| Asian | .38 | .19, .77 | .008 | .94 | .40, 2.23 | .892 |

| Other | 1.19 | .71, 2.01 | .513 | 1.12 | .48, 2.61 | .797 |

| Hispanic (ref: non-Hispanic) | .68 | .37, 1.26 | .221 | .99 | .40, 2.46 | .983 |

| Predictors of interest | ||||||

| MSA (ref: Oklahoma City) b | ||||||

| Atlanta | 1.07 | .52, 2.19 | .856 | .70 | .33, 1.48 | .350 |

| Boston | 1.49 | .76, 2.92 | .246 | .18 | .06, .53 | .002 |

| Minneapolis | 1.19 | .59, 2.40 | .624 | .50 | .23, 1.13 | .095 |

| San Diego | .75 | .35, 1.60 | .449 | .16 | .05, .50 | .002 |

| Seattle | .99 | .48, 2.03 | .973 | .20 | .07, .59 | .003 |

| Social distancing adherence | .95 | .79, 1.15 | .609 | .70 | .53, .92 | .009 |

| Sanitary adherence | .96 | .78, 1.19 | .714 | 1.06 | .79, 1.41 | .712 |

| Employment status (ref: work outside of home) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1.61 | .91, 2.82 | .099 | .62 | .25, 1.53 | .302 |

| Work from home | 1.73 | .84, 3.58 | .138 | 1.18 | .43, 3.25 | .755 |

| Switched to work from home | 1.43 | .89, 2.31 | .136 | .88 | .44, 1.75 | .706 |

| Laid off | 1.48 | .80, 2.71 | .210 | .96 | .41, 2.28 | .934 |

| New employment | 1.96 | .89, 4.34 | .095 | .28 | .04, 2.18 | .225 |

| Other | 2.15 | 1.01, 4.60 | .047 | 1.07 | .30, 3.80 | .918 |

| Household composition * | ||||||

| Partner/spouse | .78 | .52, 1.18 | .246 | 1.72 | .90, 3.28 | .101 |

| Children | .70 | .38, 1.29 | .247 | .57 | .23, 1.39 | .217 |

| Others (other than partner/children) | .86 | .57, 1.30 | .477 | 1.07 | .55, 2.09 | .848 |

| Political orientation (ref: no lean) | ||||||

| Democrat | 1.51 | .86, 2.66 | .152 | .92 | .43, 1.95 | .819 |

| Republican | .94 | .44, 1.99 | .874 | 1.17 | .49, 2.78 | .730 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | .081 | |||||

Notes * Dummy coded, so each is compared to “no” for that variable. a 69 participants responded as “other” and were thus excluded from analyses. b 198 participants resided in “other” MSA at W5 and were excluded from primary analyses

Mental health outcomes

In bivariate analyses (Table 1), correlates of greater symptoms of depression/anxiety (per the PHQ-4) included residing in Minneapolis or Seattle (vs. Atlanta or San Diego, p < .001), reporting greater social distancing adherence (p < .001) and greater sanitary adherence (p = .037), not residing with children (p = .001) but residing with others (not children or partner/spouse, p = .040), and being Democrat (vs. no lean or Republican) and no lean (vs. Republican, p < .001), as well as being younger (p = .015), other gender (vs. female or male) or female (vs. male, p < .001), sexual minority (p < .001), and White or other race (vs. Black or Asian, p < .001). Linear regression analyses (Table 3) indicated that correlates of greater mental health symptoms included greater adherence to social distancing (p = .001) and sanitary recommendations (p = .046), being unemployed or laid off (vs. working outside of the home, p <.05), living with others (not children or partner/spouse, p = .033), identifying as Democrat vs. no lean (p = .021), and identifying as no lean vs. Republican (p = .003), as well as being female (p < .001), sexual minority (p < .001), and White (vs. Black and Asian, p < .01).

Table 3.

Linear regression analyses identifying correlates of PHQ-4 scores and COVID-related stress

| Variables | PHQ-4 | COVID-related stress | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age | –0.01 | .02 | .810 | 0.01 | .00 | .877 |

| Female (ref: male) a | 0.70 | .14 | <.001 | 0.15 | .03 | <.001 |

| Sexual orientation (ref: heterosexual) | 1.15 | .16 | <.001 | 0.08 | .04 | .023 |

| Race (ref: White) | ||||||

| Black | –0.83 | .31 | .008 | –0.28 | .07 | <.001 |

| Asian | –0.85 | .21 | <.001 | –0.01 | .05 | .816 |

| Other | 0.08 | .22 | .712 | –0.02 | .05 | .744 |

| Hispanic (ref: non-Hispanic) | –0.17 | .22 | .431 | 0.06 | .05 | .226 |

| Predictors of interest | ||||||

| MSA (ref: Oklahoma City) b | ||||||

| Atlanta | –0.07 | .27 | .792 | 0.04 | .06 | .547 |

| Boston | –0.13 | .27 | .636 | 0.08 | .06 | .165 |

| Minneapolis | 0.13 | .28 | .626 | 0.15 | .06 | .016 |

| San Diego | –0.29 | .28 | .290 | 0.12 | .06 | .046 |

| Seattle | 0.21 | .28 | .453 | 0.11 | .06 | .072 |

| Social distancing adherence | 0.26 | .08 | .001 | 0.04 | .02 | .030 |

| Sanitary adherence | –0.17 | .09 | .046 | 0.08 | .02 | <.001 |

| Employment status (ref: work outside of home) | ||||||

| Unemployed | 0.51 | .22 | .020 | 0.04 | .05 | .360 |

| Work from home | 0.10 | .30 | .752 | 0.02 | .07 | .746 |

| Switched to work from home | –0.23 | .18 | .209 | 0.05 | .04 | .193 |

| Laid off | 0.83 | .24 | <.001 | 0.21 | .05 | <.001 |

| New employment | 0.21 | .34 | .540 | 0.13 | .08 | .080 |

| Other | 0.36 | .35 | .313 | 0.04 | .08 | .638 |

| Household composition * | ||||||

| Partner/spouse | 0.29 | .17 | .083 | 0.04 | .04 | .308 |

| Children | –0.42 | .22 | .062 | 0.05 | .05 | .286 |

| Others (other than partner/children) | 0.37 | .17 | .033 | 0.04 | .04 | .261 |

| Political orientation (ref: no lean) | ||||||

| Democrat | 0.47 | .20 | .021 | 0.12 | .05 | .007 |

| Republican | –0.78 | .26 | .003 | –0.05 | .06 | .400 |

| Adjusted R2 | .102 | .072 | ||||

Notes * Dummy coded, so each is compared to “no” for that variable. a 69 participants responded as “other” and were thus excluded from analyses. b 198 participants resided in “other” MSA at W5 and were excluded from primary analyses

Correlates of greater COVID-related stress, per bivariate analyses (Table 1), included residing in Minneapolis or San Diego (vs. Atlanta or Oklahoma City, p = .001), reporting greater adherence to social distancing and sanitary recommendations (p < .001), and identifying as Democrat (vs. no lean or Republican, p < .001), as well as being female or other gender (vs. male, p < .001), sexual minority (p < .001), and White, Asian, or other race (vs. Black, p < .001). Linear regression analyses (Table 3) indicated correlates of greater COVID-related stress included residing in Minneapolis and San Diego (vs. Oklahoma City, p < .05), reporting greater adherence to social distancing (p = .030) and sanitary recommendations (p < .001), being laid off (vs. working outside of home, p < .001), and identifying as Democrat (vs. no lean, p = .007), as well as being female (p < .001), sexual minority (p = .023), and White (vs. Black, p < .001).

Discussion

In this sample of young adults across six US MSAs, few participants had tested positive for COVID-19 by Fall 2020 (3%) or experienced symptoms but were not tested (7%), with the remaining 90% experiencing no symptoms or testing negative. However, nearly a third reported at least moderate depressive and anxiety symptoms, which is a higher proportion than in the general adult population during the pandemic (19.9%) but lower relative to those ages 18–39 (38.8%), as indicated in one study conducted in March–April 2020 (during the most restrictive period of the pandemic) (Ettman et al. 2020; Moreland et al. 2020). Moreover, the COVID-related stress measure indicated “somewhat more” on average across feeling down/depressed and anxious/stressed out, and experiencing more conflict in the home.

One important finding is that less adherence to social distancing recommendations was associated with testing positive for COVID-19 (vs. having no symptoms/negative test) but also with better mental health outcomes. It is also notable that, in this sample, average adherence to COVID-related preventive measures – both social distancing and sanitary recommendations – was relatively high, perhaps related to the large proportion of the sample identifying as Democrats (73%), who have been shown to be more supportive of and compliant with social distancing measures (Center for Economic Policy Research 2020). Moreover, identifying as Democrat also correlated with worse outcomes on both mental health measures, which may be attributed not only to greater adherence to social distancing measures but also the myriad of societal stressors that occurred in the year coinciding with the initial COVID-19 outbreak (i.e., racial injustices, political unrest) (Alexander 2020; Njoku et al. 2021).

In addition, compared to those reporting no symptoms/negative test, those testing positive for COVID-19 were more likely to live in Oklahoma City (relative to the other MSAs, i.e., Boston, San Diego, or Seattle – but not Atlanta and Minneapolis), where state orders were the least restrictive (Moreland et al. 2020); see Fig. 1. On the other hand, greater COVID-related stress was reported among those in Minneapolis and San Diego (relative to Oklahoma City), where state orders were the most restrictive (Moreland et al. 2020). Also noteworthy is that Minneapolis was the setting of George Floyd’s death in May, 2020, which was also a trigger for increased mental health symptoms in the USA, particularly among Black Americans (Eichstaedt et al. 2021).

With regard to other household factors, those who were unemployed or laid off (vs. working outside of the home) reported greater mental health symptoms and COVID-related stress, which aligns with the greater body of literature regarding the impact of unemployment on mental health (Bartelink et al. 2020). It is noteworthy that, in this sample of young adults, there was wide variability in the employment circumstances, with nearly 30% either switching to working from home, continuing to work outside the home, or being unemployed/laid off, respectively. In addition, those who lived with people other than spouses/partners or children reported greater mental health symptoms, which also aligns with findings that those who were married versus single reported better mental health during the pandemic (Ettman et al. 2020).

In terms of sociodemographic correlates, relative to those reporting no symptoms/negative test, those reporting symptoms but not being tested were more likely to identify as White relative to Asian. While this finding does not seem to call for alarm, it is also noteworthy that racial/ethnic minorities, specifically people of color, have been shown to be at increased risk of exposure to COVID-19, and thus, finding no differences in testing may reflect findings from other studies underscoring the incongruence between exposure and testing among people of color (Rubin-Miller et al. 2020), and that – when they are tested – they have been more likely to test positive and require a higher level of care (Acosta et al. 2021; Artiga et al. 2020; Escobar et al. 2021; Rubin-Miller et al. 2020). Also note that there were no differences across racial/ethnic groups with regard to testing positive for COVID-19, which may be a result of the small number of positive cases in this sample.

In addition, those testing positive for COVID-19 (vs. reporting no symptoms/negative test) were more likely male. Prior research indicates no differences between men and women in prevalence of COVID-19 (in terms of confirmed cases) but that men disproportionately die of COVID-19 (Ambrosino et al. 2020). While the finding in this sample of young adults is difficult to interpret, it may be a reflection of the severity of symptoms experienced by men that then resulted in testing, and thus a confirmed case. However, it may also be due to a myriad of social circumstances (e.g., staying at home during school closures) that may reduce exposure to the virus among women (Kopel et al. 2020), or the fact that women are more adherent to social distancing measures than men (Galasso et al. 2020; Pollak et al. 2020).

Regarding sociodemographic factors associated with mental health outcomes, female and sexual minority young adults reported greater mental health symptoms and COVID-related stress (Ettman et al. 2020; National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2020), which coincides with existing research (Acosta et al. 2021; Magson et al. 2021). In addition, White young adults also reported worse mental health outcomes, which situates within a complex literature regarding racial/ethnic differences in mental health and the extent to which how it is operationalized and measured may impact estimates of mental health symptoms and disorders across racial/ethnic groups (Williams 2018).

Current findings have implications for research and practice. First, intervention efforts should be informed by relevant predictors of adverse COVID-related and mental health outcomes. For instance, both this work and previous studies have shown that those who test positive for COVID-19 are more likely to be male and identify as Republican. Therefore, public health campaigns targeting these demographics may have the greatest impact in reducing the spread of COVID-19. Furthermore, those who report higher adherence to public health measures such as social distancing (e.g., females, Democrats) are more likely to experience adverse mental health outcomes, even though they also experience better COVID-related physical health outcomes (Center for Economic Policy Research 2020; Galasso et al. 2020; Leiter et al. 2021; Pedersen and Favero 2020). Therefore, it is important to explore ways in which the mental health of these populations can be supported while simultaneously maintaining these positive public health behaviors. Despite the existing work already being done to identify these populations and inform intervention research, further research is needed to determine the most effective interventions (Allcott et al. 2020; Pollak et al. 2020; Varma et al. 2021).

Limitations of this study

The current findings should be interpreted in light of some limitations, including lack of generalizability to other young adult populations across the U.S. or globally, as well as the potential for bias given the use of self-reported data. Moreover, the outcome regarding COVID-19 symptomatology, testing, and diagnosis is limited in the extent to which reasons for testing or not being tested were assessed and accounted for. In addition, there may be other environmental or interpersonal factors which were not accounted for in this analysis (e.g., type of occupation, overall household income, experience of knowing someone else diagnosed with COVID-19).

Conclusion

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues it is more important than ever, particularly in light of new variants, to understand relevant predictors and risk factors for COVID-related physical and mental health outcomes. This study has shown that despite the benefits of social distancing on curbing the pandemic, social distancing related measures, household factors and individual attitudes (e.g., political) and behaviors that restrict social interaction (e.g., state orders, employment, household composition) have implications for mental health. Specifically, males and those identifying as Republican are at higher risk of negative physical COVID-19 outcomes, while females, Democrats, sexual minorities, and those who are unemployed and single/unmarried are at higher risk of negative mental health outcomes. These individual and contextual factors provide potential targets and should therefore inform future research, intervention, and policy solutions.

Authors’ contributions

CJB conceptualized the parent study and collected the data. RDC, KFR, and CJB conceptualized the current study/analyses and led the writing of the initial manuscript. KFR managed the data. RDC and KFR conducted data analyses, with oversight from CJB, YW, and YM. All authors contributed to the writing of the final version of the paper and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute [R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg; R01CA215155-04S1; PI: Le]. Dr. Berg is also supported by other US National Institutes of Health funding, including the National Cancer Institute [R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Levine; R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg], the Fogarty International Center [R01TW010664-01; MPIs: Berg, Kegler], the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Fogarty [D43ES030927-01; MPIs: Berg, Caudle, Sturua], and the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R56DA051232-01A1; MPIs: Berg, Cavazos-Rehg].

Availability of data

Data not publicly available (available upon request).

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval statement

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Emory University (IRB00097895).

Consent to participate

All participants provided consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interests/competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acosta AM, Garg S, Pham H, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of COVID-19–associated hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and in-hospital death in the United States from March 2020 to February 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130479. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JC (2020) The Double Whammy Trauma: Narrative and counter-narrative during Covid-Floyd. https://ccs.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Alexander%20Articles/2020_The%20Double%20Whammy%20Trauma.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2022

- Allcott H, Boxell L, Conway J, Gentzkow M, Thaler M, Yang D. Polarization and public health: partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. J Public Econ. 2020;191:104254. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino I, Barbagelata E, Ortona E et al (2020) Gender differences in patients with COVID-19: A narrative review. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 90(2). 10.4081/monaldi.2020.1389 [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Constitution Society (2020) State preemption and local responses in the pandemic https://www.acslaw.org/expertforum/state-preemption-and-local-responses-in-the-pandemic/. Published 2020. Accessed 2021

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. doi: 10.3390/nu12061583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S, Corallo B, Pham O (2020) Racial disparities in COVID-19: Key findings from available data and analysis. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/racial-disparities-covid-19-key-findings-available-data-analysis/. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Bartelink VHM, Zay Ya K, Guldbrandsson K, Bremberg S. Unemployment among young people and mental health: A systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2020;48(5):544–558. doi: 10.1177/1403494819852847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Duan X, Getachew B, et al. Young adult e-cigarette use and retail exposure in 6 US metropolitan areas. Tob Regul Sci. 2021;7(1):59–75. doi: 10.18001/TRS.7.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Economic Policy Research (2020) COVID economics vetted and real-time papers. CEPR Press. https://iris.unibocconi.it/retrieve/handle/11565/4026151/122470/CovidEconomics4.pdf#page=107. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Chiesa V, Antony G, Wismar M, Rechel B. COVID-19 pandemic: health impact of staying at home, social distancing and ‘lockdown’ measures—a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Public Health. 2021;43(3):e462–e481. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche C, Garuccio J, Le A, Pinkston J, Yelowitz A. Strong social distancing measures in the United States reduced the COVID-19 growth rate. Health Aff. 2020;39(7):1237–1246. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy (2021) States’ COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Declarations and Mask Requirements. National Academy for State Health Policy. https://www.nashp.org/governors-prioritize-health-for-all/. Accessed 1 Dec 2021

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(1):157–160. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhaheri ASA, Bataineh MF, Mohamad MN, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life: Is there any effect? A cross-sectional study of the MENA region. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0249107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichstaedt JC, Sherman GT, Giorgi S, et al. The emotional and mental health impact of the murder of George Floyd on the US population. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(39):e2109139118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2109139118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes: retrospective cohort study in an integrated health system. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(6):786–793. doi: 10.7326/M20-6979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasso V, Pons V, Profeta P, Becher M, Brouard S, Foucault M. Gender differences in COVID-19 attitudes and behavior: Panel evidence from eight countries. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(44):27285–27291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2012520117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopel J, Perisetti A, Roghani A, Aziz M, Gajendran M, Goyal H. Racial and gender-based differences in COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:418. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korevaar HM, Becker AD, Miller IF, Grenfell BT, Metcalf CJE, Mina MJ (2020) Quantifying the impact of US state non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission (p. 2020.06.30.20142877). https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.30.20142877v1. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter D, Reilly J, Vonnahme B. The crowding of social distancing: How social context and interpersonal connections affect individual responses to the coronavirus. Soc Sci Q. 2021;102(5):2435–2451. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.13060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(1):44–57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreland A, Herlihy C, Tynan M (2020) Timing of state and territorial COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and changes in population movement—United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935a2.htm. Accessed 5 June 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National Survey on Drug Use and Health (2020) 2018 National survey on drug use and health: Lesbian, Gay, & Bisexual (LGB) Adults. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-nsduh-lesbian-gay-bisexual-lgb-adults. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Njoku A, Ahmed Y, Bolaji B. Police brutality against Blacks in the United States and ensuing protests: implications for social distancing and Black health during COVID-19. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2021;31(1–4):262–270. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2020.1822251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MJ, Favero N. Social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Who are the present and future noncompliers? Public Adm Rev. 2020;80(5):805–814. doi: 10.1111/puar.13240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Y, Dayan H, Shoham R, Berger I (2020) Predictors of adherence to public health instructions during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.24.20076620 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Public Health Law Center (2020) Commercial tobacco and marijuana. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/commercial-tobacco-and-marijuana. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Rubin-Miller L, Alban C, Artiga S, Sullivan S (2020) COVID-19 racial disparities in testing, infection, hospitalization, and death: analysis of epic patient data. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-racial-disparities-testing-infection-hospitalization-death-analysis-epic-patient-data/. Accessed 5 June 2022

- Theis N, Campbell N, De Leeuw J, Owen M, Schenke KC. The effects of COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity and mental health of children and young adults with physical and/or intellectual disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(3):101064. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma P, Junge M, Meaklim H, Jackson ML. Younger people are more vulnerable to stress, anxiety and depression during COVID-19 pandemic: a global cross-sectional survey. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;109:110236. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR. Stress and the mental health of populations of color: advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. J Health Soc Behav. 2018;59(4):466–485. doi: 10.1177/0022146518814251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data not publicly available (available upon request).

Not applicable.