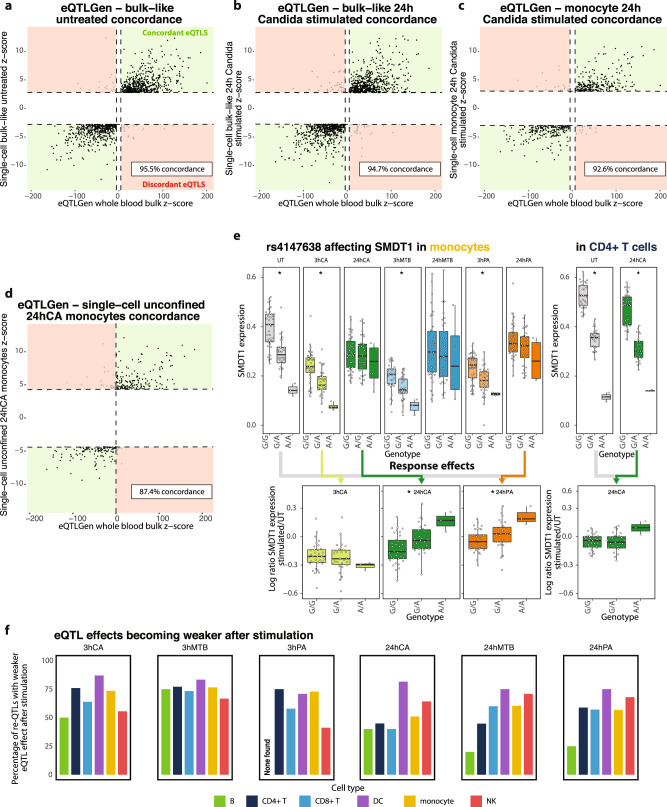

Fig. 3. eQTLs and re-QTLs upon pathogen stimulation.

Concordance between the eQTLs identified in 31,684 bulk whole-blood samples of the eQTLGen consortium and: a those identified in our eQTLGen lead-eSNP discovery of bulk-like unstimulated PBMC scRNA-seq data, (b) those identified in our eQTLGen lead-eSNP discovery of bulk-like 24 h C. albicans (CA)-stimulated PBMC scRNA-seq data, (c) those identified in our eQTLGen lead-eSNP discovery of monocyte 24 h CA-stimulated PBMC scRNA-seq data, and (d) those identified in our genome-wide eQTL discovery of monocyte 24 h CA-stimulated PBMC scRNA-seq data. e Boxplots showing the effect of the rs4147638 genotype on SMDT1 expression in the untreated (UT) condition and each of the six stimulation‒timepoint combinations in the monocytes (left) or for the UT and 24 h CA condition in the CD4+ T cells (right). Boxplots show median, first and third quartiles, and 1.5× the interquartile range, and each dot represents the average expression of all cells per cell type and individual. Stars indicate a significant effect (FDR < 0.001). The log ratio of SMDT1 expression in the UT cells vs a specific stimulation-timepoint combination is shown in the bottom. Colored arrows indicate which specific stimulation‒timepoint combination was selected for the corresponding re-QTL boxplot. f The proportion of re-QTLs of which the eQTL effect became weaker after stimulation, split per cell type and stimulation‒timepoint combination. eQTL summary statistics for eQTLGen-confined analysis, genome-wide analysis and response-QTL analysis can be found in Supplementary Data 7, Supplementary Data 8, and Supplementary Data 9, respectively. The number of individuals and cells included in each analysis can be found in the Source Data file.