Abstract

Discovering and developing the desired antimalarials continue to be a necessity especially due to treatment failures, drug resistance, limited availability and affordability of antimalarial drugs and costs especially in poor malarial endemic countries. This study investigated the efficacies of two plant cocktails; CtA and CtB, selected based on their traditional usage. Efficacies of the cocktail extracts, chloroquine and pyrimethamine against Plasmodium berghei berghei were evaluated in mice using the suppressive, curative and prophylactic test models, after oral and intraperitoneal acute toxicity determination of the plant cocktails in accordance with Lorke’s method. Data was analyzed using SPSS software version 23.0 with level of significance set at P < 0.05. The median lethal dose was determined to be higher than 5000 mg/kg body weight orally for both CtA and CtB; and 316.23 mg/kg body weight intraperitoneally for CtA. Each cocktail exhibited high dose dependent Plasmodium berghei berghei inhibition which was 96.95% and 99.13% in the CtA800 mg/kg and CtB800 mg/kg doses in the curative groups respectively, 96.46% and 78.62% for CtA800mg/kg and CtB800mg/kg doses in the suppressive groups respectively, as well as 65.05% and 88.80% for CtA800mg/kg and CtB800mg/kg doses in the prophylactic groups respectively. Throughout the observation periods, the standard drugs, chloroquine phosphate and pyrimethamine maintained higher inhibitions up to 100%. These findings demonstrate that CtA and CtB possess good antimalarial abilities and calls for their development and standardization as effective and readily available antimalarial options. The acute toxicity results obtained underscore the importance of obtaining information on toxicities of medicinal plant remedies before their administration in both humans and animals.

Keywords: Antimalarial efficacy, Medicinal plants, Cocktail remedies, Acute toxicity

Introduction

Malaria remains a major health problem and continues to impact enormously on human health and economy (WHO-WMR 2016). Effective malaria control and eradication depend largely on high-quality case management, vector control and surveillance (WHO 2006,2012,2014). Treatment with efficacious antimalarial drugs is crucial at all stages including the early control or ‘‘attack’’ phase to driving down transmission and the later stages of maintaining interruption of transmission, preventing reintroduction, and eliminating the last residual foci of infection (Bhatt et al. 2015; WHO 2007, 2014, 2016). Substantial work is under way on new drugs to counter vector resistance, safely target hypnozoites (radical cure), clear gametocytes and prevent reinfection (Wells et al. 2015; Burrows et al. 2013).

Plants may well prove to be the source of new antimalarial drugs in view of the success with the two important chemotherapeutic agents, quinine and artemisinin (the mainstay of malaria treatment), both of which are derived from plants (Ojurongbe et al. 2015). However, the use of Quinine and Artemisinin as antimalarials has been limited by incidences of Plasmodium strains developing resistance against them (WHO-WMR 2011; Ménard et al. 2013; Ashley et al. 2014). Medicinal plants traditionally used to treat malaria therefore continues to be increasingly investigated for ideal antimalarial drug discovery and development.

There is a growing consensus that drug combinations are essential to the optimal control of malaria, since they offer improved efficacy through synergistic activities (Fidock et al. 2004). Artemisinin-based Combination Therapies (ACTs)—particularly combinations of artemisinin or its semi-synthetic derivatives and a long-lasting drug—are recommended by WHO for treating P. falciparum infections (WHO 2001a,2015; b; Faurant 2011; Dawaki et al. 2016). Consequently, drug combination therapy, including the use of polyherbal products, has become the popular method of managing malaria morbidity (Arrey et al. 2014). In recent times, several concoctions of two or more whole plant species or their parts that work in synergy are prepared and administered orally (Adjanohoun et al. 1996; Adebayo and Krettli 2011; Ajayi et al. 2017). Despite the increasing level of dependence on this method of management, only a few pharmacological investigations have been carried out on the ever-increasing number of indigeneous polyherbal preparations used to treat malaria fever (Table 1) (Nwabuisi 2002; Ofori-Attah et al. 2012; Martey et al. 2013; Idowu et al. 2015; Adepiti et al. 2016; Okpe et al. 2016; Ibukunoluwa 2017; Orabueze et al. 2018). Also, toxicity assessment of these polyherbal preparations are rarely investigated, making it difficult to be generally accepted as safe to public health.

Table 1.

Previous studies validating plant cocktails in malaria treatment

| Plant species | Antiplasmodial activities | Safety studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cajanus cajan + Euphorbia lateriflora + Mangifera indica + Cassa alata + Cymbopogon giganteus + Nauclea latifolia + Uvaria chamae | Significant antiplasmodial activity | No significant side effects | Nwabuisi (2002) |

| Azadirachta indica + Nauclea latifolia + Morinda lucida | 54.07% chemo-suppression | Not done | Ofori-Attah et al. (2012) |

| Azadirachta indica + Nauclea latifolia + Morinda lucida | 50.6% chemo-suppression | No adverse effects | Martey et al. (2013) |

| Nauclea latifolia + Artocarpus altilis + Murraya koenigii + Enantia chlorantha | 52.7% curative, 60.2% prophylactic activities | Not done | Adebajo et al. (2014) |

| Ficus exasperata + Anthocleista vogelii | 91.7% chemo-suppression | Increased size of liver, spleen | Okon et al. (2014) |

| Picralima nitida + Alstonia boonei + Gongronema Latifolia | 86.16% curative, 54.68% suppressive activities | Elevated ALT, AST and creatinine | Idowu et al. (2015) |

| Mangifera indica + Alstonia boonei + Morinda lucida + Azadirachta indica | 55% curative activities and 43% chemo-suppression | Not done | Adepiti et al. (2014, 2016) |

| Vernonia amygdalina + Carica papaya | Significant antiplasmodial curative activity | Increased RBC and PCV. Histology indicated hepatic cell damage | Okpe et al. (2016) |

| Anthocleista djalonensis A. Chev. + Azadirachta indica A. Juss + Cajanus cajan (L.) Huth. + Crescentia cujete L. + Lawsonia inermis L. + Lophira alata Banks ex C.F. Gaertn. + Myrianthus pruessii Engl. + Nauclea latifolia Sm. + Olax subscorpioidea Oliv. + Terminalia glaucescens | Significant antiplasmodial curative activity | Histological studies revealed some pathology | Ibukunoluwa (2017) |

| Fadogia cienkowskii + Lophira lanceolata + Vernonia conferta + Protea madiensis | 74.% curative, 85.1% suppressive activities | No adverse effects | Orabueze et al. (2018) |

| Mangifera indica + Carica papaya + Citrus limon | Significant antiplasmodial activity | Malaria associated splenic pathology, anemia | Moronkeji et al. (2019) |

Enantia chlorantha (African yellow wood), Cymbopogon citratus (Lemon grass), Carica papaya (Pawpaw), Mangifera indica (mango), Curcuma longa (Tumeric), Alstonia boonei (Pattern wood) are some of the predominantly used antimalarial medicinal plants in most endemic countries including Nigeria. Previous studies have demonstrated monotherapeutic activities of extracts from these plants against malaria (Table 2). Despite their popular application in combination antimalarial ethnomedicine, there is no scientific evidence to justify the acclaimed antimalarial efficacy when combined. Therefore, the present study evaluated in vivo antimalarial efficacy and acute toxicity of two plant cocktail extracts in mice following ethno botanical survey of traditional medicine practicioners (Omagha et al. 2021). The scientific justification of the plant cocktails being investigated may be a springboard for new phytotherapies that could be affordable to treat malaria in Nigeria and in other parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, the most malaria endemic areas in the world.

Table 2.

Antimalarial activities of plants selected for the study

| Plant species | Antiplasmodial activities | References |

|---|---|---|

| Enantia chlorantha | 53% prophylactic, 56.4% chemosuppressive, 49.7 curative activities | Adebajo et al. (2014) |

| Cymbopogon citratus | 80.56% chemo-suppression | Arome et al. (2016) |

| Curcuma longa | 34.6% chemo-suppression | Agbedahunsi et al. (2016) |

| Carica papaya | 61.78% chemo-suppression | Zeleke et al. (2017) |

| Alstonia boonei | 71.0% chemosuppressive, 81.36 curative, 60.67% prophylactic activities | Iyiola et al. (2011) |

| Mangifera indica | 95.82% chemo-suppression | Omoya (2016) |

Materials and methods

Preparation of plant cocktail extracts and reference drugs

Based on information collected from herbal practitioners in south west Nigeria (Omagha et al. 2021), powdered hot water extracts of A. boonei (stem bark), C. papaya (fruits), C. citratus (leaves), C. longa (roots), M. indica (stem bark) and E. chlorantha (Stem bark) were combined in ratios to prepare two popularly used polyherbal remedies from indigenous plants. Cocktail treatment A (CtA): 4:2:1 (E. chlorantha:C. citratus:C. longa). Cocktail treatment B (CtB): 4:2:1:1 (E. chlorantha:A. boonei:C. papaya:M. indica). Therefore, CtA was prepared by dissolving 5.70 g + 2.87 g + 1.43 g of E. chlorantha, C. citratus and C. longa in 200 ml distilled water equivalent to 50 mg/ml concentration; and CtB was prepared by dissolving 5.00 g + 2.33 g + 1.27 g + 1.27 g of E. chlorantha, A. boonei, C. papaya and M. indica in 200 ml distilled water equivalent to 50 mg/ml concentration. The resulting combinations were separately heated over a water bath for 30 min and left to cool, labelled and refrigerated at 4 °C in air-tight bottles. Doses administered for CtA and CtB, (200 mg/kg, 400 mg/kg and 800 mg/kg) were appropriately chosen for antimalarial evaluation based on acute toxicity results established by this study. Chloroquine phosphate (CQ) and Pyrimethamine (PY) manufactured in Ikeja, Lagos Nigeria by Vitabiotics Limited, and SKG-Pharma Limited respectively are the standard drugs used as positive controls. The doses required for each of the standard drugs, 25 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg respectively (Iwalokun 2008; Alli et al. 2011) were given according to weight of each animal. They were each prepared by diluting: 250 mg tablet strength of CQ in 25mls of distilled water (10 mg/ml), and 25 mg tablet strength of PY in 5 mL of distilled water (5 mg/ml). A measure of 10 ml/kg distilled water (DW) was given as negative control (Table 3).

Table 3.

Concentrations for treatments administered

| Treatments | Treatments and doses administered |

|---|---|

| Standard drugs | |

| Chloroquine (CQ) | CQ25 mg/kg |

| Pyrimethamine (PY) | PY5 mg/kg |

| Cocktail extracts | |

| Cocktail treatment A (CtA) | CtA200 mg/kg, CtA400 mg/kg, CtA800 mg/kg |

| Cocktail treatment B (CtB) | CtB200 mg/kg, CtB400 mg/kg, CtB800 mg/kg |

| Distilled water (DW) | DW10 mg/ml |

Plasmodium parasite species and animals

Chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei berghei parasites was obtained from Institute for Advanced Medical Research and Training, (IMRAT), University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, by intraperitoneal inoculation of uninfected mice with 0.2 ml of the diluted blood from previously infected mice maintained by successive intra-peritoneal inoculation of parasite-free mice every four days. The donor mice were then transported to the University of Lagos animal house where they were kept under standard laboratory conditions with constant access to food and water until the desired level of parasitemia was achieved. Infected blood from the donor mouse was obtained by cardiac puncture. Infected red cells/µl was calculated using the relative value method, count of infected red cells × 5,000,000/total red cells counted (infected + non-infected). This was done to determine the required standard inoculum of 1 × 106 using thin blood films of donor mice. Five millilitres normal saline, a quantity determined by the level of parasitaemia of the infected donor mice was used to dilute 2 ml of the donor blood.

A total of 120 adult male mice of about 7–8 weeks old, weighing between 16 and 20 g were obtained from the Animal House, University of Lagos, where the animal exposures was conducted. Before being subjected to experiment they were left for two weeks to acclimatize to laboratory conditions, and had constant access to feed on a standard rodent’s diet consisting of crude protein, fat, calcium, available phosphate, vitamins, crude fiber and tap water. They were kept in plastic cages with metal covers for free passage of air, and at room temperature of about 27 °C.

Acute toxicity (LD50) test of the plant cocktails

A lethal dose for 50% of the mice (LD50) was performed on the two cocktail treatments, CtA and CtB in accordance with (Lorke 1983) method. This test was done to observe the mice for signs of toxicity including clogging together, weakness, anorexia, micturition, respiratory distress, coma, and mortality for the first 24 h and thereafter daily for 14 days. The tests were replicated in two groups, group 1 treated orally and group 2 treated intraperitoneally. A total of 48 mice was used for this test. In the phase 1 of the method, 9 animals divided into three groups of 3 animals were orally administered different doses (10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg) of the test substances CtA and CtB, and observed for 24 h. Another 9 animals divided into three groups of 3 animals each were intraperitoneally administered different doses (10 mg/kg, 100 mg/kg and 1000 mg/kg) of the test substances CtA and CtB, and observed for 24 h. In the phase 2 of the method, further specific doses were administered to calculate an LD50. 3 animals divided into three groups of 1 animal each were orally administered different doses (1600 mg/kg, 2900 mg/kg and 5000 mg/kg) of CtA. This was replicated for CtB. Another 3 animals divided into three groups of 1 animal each were intraperitoneally administered different doses (1600 mg/kg, 2900 mg/kg and 5000 mg/kg) of CtA. This was replicated for CtB. The LD50 was calculated as the square root of the product of the lowest lethal dose and highest non-lethal dose, i.e., the geometric mean of the consecutive doses for which 0 and 100% survival rates were recorded in the second phase, using the formula:

LD50 = √ (D0 × D100); where D0 = highest dose that gave no mortality, D100 = lowest dose that produced 100% mortality.

Antimalarial activities of CtA and CtB

The antimalarial efficacy of the cocktail extracts CtA and CtB in rodent malaria parasites was evaluated using the suppressive, curative and prophylactic test models. The body weight of each mouse for all the tests was taken before and after exposure. 0.2 ml of the prepared P. berghei berghei parasitized erythrocytes suspension in normal saline was injected intraperitoneally into each mouse to be used for the tests using one (1) ml syringe and needle. The drugs and plant cocktails were orally administered using a cannula. Thick and thin blood smears fixed in 100% methanol and stained with 10% Giemsa’s stain at pH 7.2 for 15 min were prepared from the tail blood of each mouse. Prepared blood films were air dried at room temperature and examined microscopically for parasites under oil immersion (X100 magnification). The parasitaemia was determined by counting the number of parasitized erythrocytes in 2000 cells in randomly selected fields of the microscope. The percentage parasitaemia was determined using the formular:

Number of parasitized RBCs/Total number of RBCs (infected + Non-infected) × 100% (Fidock et al. 2004).

The mean parasite count for each group were determined and the percentage chemo inhibition for each dose was calculated as:

[(A − B)/A], where A is the average percentage of parasitaemia in the negative control and B is the average percentage of parasitaemia in the test groups (Kalra et al. 2006).

Rane curative test

It was conducted according to Ryley and Peters (1970) in a similar method adopted by Iwalokun (2008); Alli et al. (2011). Seventy-two hours after infection with chloroquine sensitive P. berghei, 40 infected mice were divided into 8 groups of 5 animals each. 3 groups were orally administered different doses (200, 400 and 800 mg/kg) of CtA. The same treatment was replicated for CtB using another 3 groups of the animals. The 7th group was administered chloroquine phosphate (25 mg/kg) as positive control, while the 8th group received 10 mg/ml distilled water as negative control. Each mouse was treated orally once daily with the dose given according to body weight of animal for 5 consecutive days (D4–D8) post inoculation during which the parasitaemia level were monitored daily.

The 4-day suppressive test

Peters (1965) 4-day suppressive test in mice was conducted in a similar method reported by Mesia et al. (2005); Iwalokun (2008); Alli et al. (2011). 40 mice divided into 8 groups of 5 animals each were inoculated intraperitoneally on the first day (Do) with Plasmodium berghei berghei parasitized red blood cells. The mice were then treated immediately after day 0 to day 3. 3 groups were orally administered different doses (200, 400 and 800 mg/kg) of CtA according to body weight of animal. The same treatment was replicated for CtB using another 3 groups of the animals. The 7th group was administered chloroquine phosphate (25 mg/kg) as positive control, while the 8th group received 10 mg/ml distilled water as negative control. All treatments were given according to body weight of animal. Parasitaemia levels were monitored daily from day 4 to day 7.

Repository (prophylactic) test

Adopted the method of Peters (1965) and as similarly followed in Alli et al. (2011). A total of 40 mice were divided into 8 groups of 5 animals. 3 groups were orally administered different doses (200, 400 and 800 mg/kg) of CtA. The same treatment was replicated for CtB using another 3 groups of the animals. The seventh group was given 5 mg/kg of pyrimethamine, while the last group (negative control) received 10 mg/ml distilled water for four consecutive days. On the fourth day (D4), the mice were inoculated with P. berghei berghei. Seventy two hours later (D7), smears were made from the mice (D7-D11) to assess parasitaemia levels.

Data analysis

Data from anti-plasmodial curative, suppressive and prophylactic assays were entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel version 2016 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23.0. The differences between means among negative and positive controls as well as treatment groups were compared for significance using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s multiple post hoc test. Differences were considered significant to negative control at Probability < 0.05.

Results

Acute toxicity of CtA and CtB in mice

Acute oral toxicity assessment of both CtA and CtB showed dose-dependent reduced activity and clogging together within the first six hours at the phase 2 treatments. All the mice survived both phases within the 24 h and 2-weeks observation periods. The oral median lethal dose of both CtA and CtB was calculated to be greater than 5000 mg/kg in mice (Table 4). In the intraperitioneal acute toxicity assessment, there were remarkable dose-dependent reduced activity and clogging together in the phase 1 treatments with 1000 mg/kg dose of both cocktails, and at all doses in phase 2 with CtB. Within 24 h, 100% mortality was recorded for CtB and 33% for CtA, though mortality for CtA reached 100% within 7 days observation period. Within 24 h, 100% mortality was recorded for CtA at all doses in phase 2. No further exposure was done for the group receiving CtA following a 100% mortality observed at 1000 mg/kg in phase 1. Acute intraperitioneal toxicity assessment was calculated to be 316.23 mg/kg in mice for CtA. (Table 5).

Table 4.

Acute toxicity (LD50) results from oral administration

| Cocktails | No of mice | Dose (mg/kg) | Weakness/reduced activity | Clogging together | Day 0 mortality | % Mortality | LD50 (mg/kg) | Day 7 mortality | Day 14 mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorke’s Phase 1 | |||||||||

| CtA | 3 | 10 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 100 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 1000 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| CtB | 3 | 10 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 100 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 1000 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Lorke’s phase 2 | |||||||||

| CtA | 1 | 1600 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 0 | CtA > 5000 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 2900 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 5000 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| CtB | 1 | 1600 | No | Yes | 0 | 0 | CtB > 5000 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 2900 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1 | 5000 | Yes | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Table 5.

Acute toxicity (LD50) results from intraperitioneal administration

| Cocktails | No of mice | Dose (mg/kg) | Weakness/reduced activity | Clogging together | Day 0 mortality | % Mortality | LD50 (mg/kg) | Day 7 Mortality | Day 14 Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lorke’s phase 1 | |||||||||

| CtA | 3 | 10 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 100 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 1000 | Yes | No | 1 | 33% | 2 | - | ||

| CtB | 3 | 10 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 100 | No | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 1000 | Yes | No | 3 | 100 | ||||

| Lorke’s phase 2 | |||||||||

| CtA | 1 | 1600 | Yes | Yes | 1 | 100 | CtA = 316.23 | ||

| 1 | 2900 | Yes | Yes | 1 | 100 | ||||

| 1 | 5000 | Yes | Yes | 1 | 100 | ||||

| CtB | 1 | 1600 | ND | ||||||

| 1 | 2900 | ND | |||||||

| 1 | 5000 | ND | |||||||

In vivo antimalarial efficacies of CtA and CtB

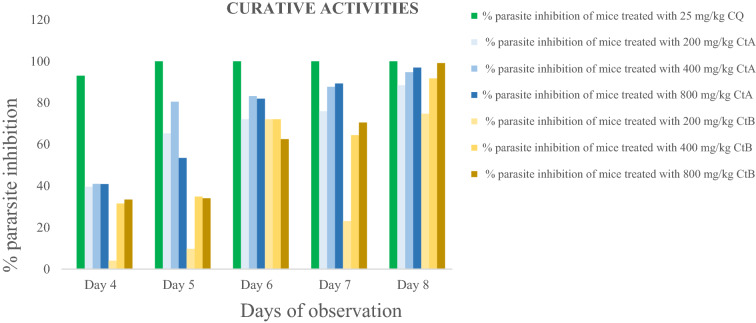

Curative ability on established infection: Curative effects in all the treated groups increased from day 4 to day 8. Parasite inhibition was 100% with CQ25 mg/kg from day 2 till day 5. In the extract treated groups, inhibition was observed to be 88.50%, 94.77% and 96.95% in the CtA200 mg/kg, CtA400 mg/kg and CtA800 mg/kg doses respectively; and 74.82%, 91.81% and 99.13% in the CtB200 mg/kg, CtB400 mg/kg and CtB800 mg/kg doses respectively.

Suppressive ability on early infection: Throughout the four days of observation, parasitaemia was 100% inhibited in the CQ25 mg/kg group. In the groups treated with the plant cocktails, inhibition increased at all doses, and by day 6, reached 63.82%, 89.54% and 96.46% at the CtA200 mg/kg, CtA400 mg/kg and CtA800mg/kg doses respectively; and 33.84%, 51.92% and 78.62% for CtB200 mg/kg, CtB400 mg/kg and CtB800mg/kg doses respectively.

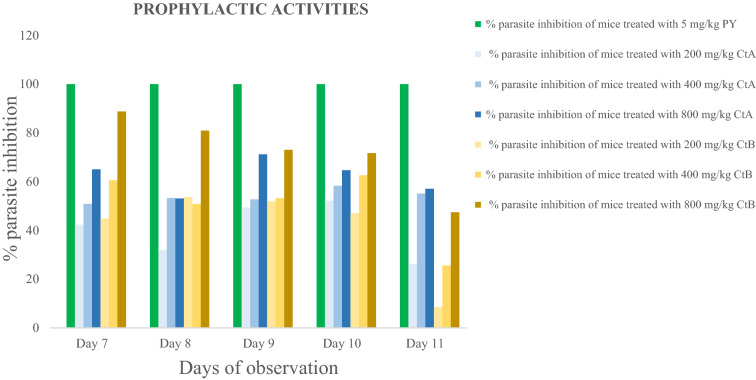

Prophylactic ability on residual infection: Result shows inhibition with PY5 mg/kg to be 100% throughout the 5 days of observation. With the cocktail extract-treated groups, at the beginning of observation (D7), parasite inhibition was 42.34%, 50.88% and 65.05% for the CtA200 mg/kg, CtA400 mg/kg and CtA800mg/kg doses respectively; and 65.05%, 60.57% and 88.80% for CtB200 mg/kg, CtB400 mg/kg and CtB800mg/kg doses respectively. However, a decreased parasite inhibition was observed as the observation proceeded, and by D11, parasite inhibition was 26.12%, 55.14% and 57.09% for the CtA200 mg/kg, CtA400 mg/kg and CtA800mg/kg doses respectively; and 8.53%, 25.59% and 47.42% for the CtB200 mg/kg, CtB400 mg/kg and CtB800mg/kg doses respectively.

Figures 1, 2 and 3 below shows the percentage inhibition of P. berghei berghei in mice.

Fig. 1.

Curative ability of treatments on established infection

Fig. 2.

Suppressive ability of treatments on early malaria infection

Fig. 3.

Prophylactic ability of treatments on residual infection

Discussion

Acute toxicity was evaluated to observe for toxicity signs and mortality associated with administration of CtA and CtB in mice. The oral and intraperitoneal routes’ toxicity effects in this study varied with dosage concentrations. Lethal oral dose of CtA and CtB was evaluated to be less than the intraperitoneal administration, emphasizing a need to establish any toxicity before choosing the routes of administration. These findings suggests the safe use of the plants by the locals who reported oral route as the most popular mode of administration of these cocktail recipes in malaria treatment (Omagha et al. 2021). Though intraperitoneal administration is sometimes preferred over the oral route as high concentration of the drug is able to bypass the physiological barriers and provide the highest bioavailability and the fastest effect (Cardenas et al. 2017), administering large volumes intraperitioneally (> 10 ml/kg in rodents) can lead to pain, chemical peritonitis, formation of fibrous tissue, perforation of abdominal organs, hemorrhage, and respiratory distress (Bredberg et al. 1994; Esquis et al. 2006). These concerns of potential adverse effects may necessitate more favorable routes of herbal remedy administration. The toxic effects reported for these cocktail recipes in mice is expected to serve as baseline for further studies, for comparison in mammalian anatomy and physiology (Ibukunoluwa 2017; Jutamaad et al. 1998) and encourage advocacies for their regulated oral use as complementary therapies. The results of acute toxicity generally serve in choosing appropriate test doses of CtA and CtB for antimalarial evaluation in investigation.

Earlier studies have reported the traditional antimalarial uses (Agbaje and Onabanjo 1991; Awe et al. 1998; Bhat and Surolia 2001; Udeh et al. 2001; Aiyeloja and Bello 2006; Idowu et al. 2010) and the monotherapeutic activities (Adebajo et al. 2014; Arome et al. 2016; Agbedahunsi et al. 2016; Zeleke et al. 2017; Iyiola et al. 2011; Omoya 2016) of C. papaya, C. longa, A. boonei, M. indica, E. chlorantha and C. citratus. This study reports the antiplasmodial activity of two polyherbal recipes from the above mentioned plants: CtA comprising E. chlorantha + C. citratus + C. longa, and CtB comprising E. chlorantha + A. boonei + C. papaya + M. indica. Similar investigation on the antiplasmodial activities of some other polyherbal recipes in malaria treatments have reported noteworthy efficacies (Nwabuisi 2002; Ofori-Attah et al. 2012; Martey et al. 2013; Adebajo et al. 2014; Idowu et al. 2015; Okpe et al. 2016, Ibukunoluwa 2017; Orabueze et al. 2018).

In all three models (curative, suppressive and prophylactic), results showed that CtA and CtB significantly inhibited parasitaemia, with inhibition levels up to 90% in the 400 and 800 mg/kg doses of each cocktail extracts in the curative and suppressive models. The findings confirms antiplasmodial potency of CtA and CtB, provides scientific basis for their usage as antimalarial remedies and proves they are potential sources that should be explored for new antimalarial drugs. Chloroquine, an antimalarial drug still widely used in Nigeria because it is accessible and affordable, and despite WHO recommendation for Artemisinin Combination Therapies ACTs (WHO 2001a; b; Oladipo et al. 2015) was used as the reference drug in the curative and suppressive models (Iwalokun 2008; Alli et al. 2011), and Pyrimethamine was the standard antimalarial drug used in the prophylactic model (Alli et al. 2011). These standard drugs inhibited parasitaemia to undetectable levels and the findings agrees with results from other studies validating medicinal plants in malaria treatments (Alli et al. 2011; Ogbole et al. 2014). Of note, the total clearance of parasitaemia by chloroquine compares very closely to the 99.13% curative ability demonstrated by CtB at 800 mg/kg in this study, and therefore a potential starting point to develop new treatment that is better suited to effectively treat malaria.

Phytochemical analysis plays a vital role in the observation of the efficacies of the plant materials in therapeutic preparations (Gebrehiwot et al. 2019). The antiplasmodial activity observed in these plant cocktails could be attributed to the presence of some of the antimalarial proven phytochemicals including saponin, alkaloid, flavonoid, phenol and lactones (Kirby et al. 1989; Philipson and Wright 1991; Christensen and Kharazmi 2001; Onifade and Maganda 2015; Ibukunoluwa 2017; Omagha et al. 2020) present in each of the plants used in the combinations for CtA and CtB. These phytoconstituents affect the condition and function of body organs, clear up residual symptoms of the disease. They help increase the body’s resistance to disease or facilitate the adaptation of the organism to certain conditions (Njan 2012). However, the potential toxicity of plant products is understudied. A few scientific evidences available from toxicological studies have reported some phytochemicals to be potentially toxic thus affecting their safe use (Bode and Dong 2015; Mensah et al. 2019).

Multidrug strategy in therapeutic applications is expected to increase efficacy of two or more anti-infective agents (Bennet et al. 2015), improve clinical cure, shorten the duration of therapy so as to minimize the risk of recrudescence, and provide a way in which resistance can be delayed (WHO 2001a; b). Our results showed that the action of the combination therapies in this study significantly differed from the plant materials acting individually in previous studies (Agbaje and Onabanjo 1991; Longdet and Adoga 2017; Awe et al. 1998; Onifade and Maganda 2015). The improved efficacy demonstrated by these findings and extent of use by locals who rely on them to combat high burdens of malaria morbidity and mortality calls for further studies to understand activities and actual behaviours of these combined plant materials in malaria treatments.

Conclusions

Malaria control continues to rely upon antimalarial plant remedies increasingly used as combination therapies. Findings in this study demonstrates that plant-based cocktail treatments CtA and CtB possess good antimalarial abilities and safer in oral administrations compared to intraperitioneal administrations. Following the efficacies established in this study, further investigations concerning their safety is currently ongoing to determine the potential toxicity-related adverse reactions while using CtA and CtB in malaria treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Prof. O. G. Ademowo of the Institute of Advanced Medical Research and Training (IMRAT), University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria, for kindly supplying the rodent parasite, Plasmodium berghei berghei NK 65. Dr. Akeem Kadiri, Department of Botany and Microbiology, University of Lagos, Lagos Nigeria is also appreciated for assistance identifying the 6 plant materials collected from medicinal plants growers at Oje, Ibadan. Mr. Samuel Akindele and Mr Olakiigbe A.K. of the Department of Biochemistry, Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), Yaba, Lagos is also acknowledged for technical assistance.

Authors’ contributions

Omagha R. conceptualized the idea for this study and wrote the research proposal. Idowu E.T, Alimba C.G., Otubanjo O.A., Agbaje E.O. reviewed the research proposal and contributed to improving the experimental design. Oyibo W.A. made provisions for the lab space for the animal exposure. Omagha R. conducted the research and drafted the manuscript. All the authors participated in reviewing and approving the work for publication.

Funding

Not applicable.

Declartions

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Ethics Committee at the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research Institutional Review Board (NIMR IRB) reviewed and granted approval (Assigned Number IRB/17/036) for this study.

Informed consent

This study involving laboratory mice for antimalarial experiments were carried out following Nigerian Institute of Medical Research Institutional Review Board’s guidelines for laboratory animal care and use.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adebayo JO, Krettli AU. Potential antimalarials from Nigerian plants: a review. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133(2):289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebajo AC, Odediran SA, Aliyu FA, Nwafor PA, Nwoko NT, Umana US. In vivo antiplasmodial potentials of the combinations of four Nigerian antimalarial plants. Molecules. 2014;19(9):13136–13146. doi: 10.3390/molecules190913136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adepiti AO, Elujoba AA, Bolaji OO. Evaluation of herbal antimalarial MAMA decoction-amodiaquine combination in murine malaria model. Pharm Biol. 2016;54(10):2298–2303. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2016.1155626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjanohoun JE, Aboubakar N, Dramane K et al. (1996) Contribution to ethnobotanical and floristic studies in Cameroon, Scientific, Technical and Research Commission, Organization of African Unity, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- Agbaje EO, Onabanjo AO. The effects of extracts of Enantia chlorantha in malaria. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1991;85(6):585–590. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1991.11812613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbedahunsi JM, Adepiti AO, Adedini AA, Akinsomisoye O, Adepitan A. Antimalarial properties of Morinda lucida and Alstonia boonei on sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine and curcuma longa on quinine in mice. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2016;22(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/10496475.2014.999151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aiyeloja AA, Bello OA. Ethnobotanical potentials of common herbs in Nigeria: a case study of Enugu state. Educ Res Rev. 2006;1(1):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi EIO, Adeleke MA, Adewumi TY, Adeyemi AA. Antiplasmodial activities of ethanol extracts of Euphorbia hirta whole plant and Vernonia amygdalina leaves in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. J Taibah Univ Sci. 2017;11(6):831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jtusci.2017.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alli LA, Adesokan AA, Salawu OA, Akanji MA, Tijani AY. Anti-plasmodial activity of aqueous root extract of Acacia nilotica. Afr J Biochem Res. 2011;5(7):214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Arrey Tarkang P, Franzoi KD, Lee S, Lee E, Vivarelli D, Freitas-Junior L, Okalebo FA (2014) In vitro antiplasmodial activities and synergistic combinations of differential solvent extracts of the polyherbal product, Nefang. BioMed Res Int 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Arome D, Chinedu E, Ameh SF, Sunday AI. Comparative antiplasmodial evaluation of Cymbopogon citratus extracts in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. J Curr Res Sci Med. 2016;2(1):29. doi: 10.4103/2455-3069.184126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sopha C. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awe SO, Olajide OA, Oladiran OO, Makinde JM. Antiplasmodial and antipyretic screening of Mangifera indica extract. Phytother Res Int J Devot Pharmacol Toxicol Eval Nat Prod Derivat. 1998;12(6):437–438. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet JE, Blaser MJ, Dolin R (2015) Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Elsevier Saunders.

- Bhat GP, Surolia N. In vitro antimalarial activity of extracts of three plants used in the traditional medicine of India. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65(4):304–308. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Weiss DJ, Cameron E, Bisanzio D, Mappin B, Dalrymple U, Wenger EA. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015;526(7572):207. doi: 10.1038/nature15535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AM, Dong Z. Toxic phytochemicals and their potential risks for human cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2015;8(1):1–8. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredberg E, Lennernäs H, Paalzow L. Pharmacokinetics of levodopa and carbidopa in rats following different routes of administration. Pharm Res. 1994;11(4):549–555. doi: 10.1023/A:1018970617104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows JN, van Huijsduijnen RH, Möhrle JJ, Oeuvray C, Wells TN. Designing the next generation of medicines for malaria control and eradication. Malar J. 2013;12(1):187. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas PA, Kratz JM, Hernández A, Costa GM, Ospina LF, Baena Y, Aragon M (2017) In vitro intestinal permeability studies, pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of 6-methylcoumarin after oral and intraperitoneal administration in Wistar rats. Braz J Pharm Sci 53

- Christensen SB, Kharazmi A (2001) Antimalarial natural products. Isolation, characterization and biological properties In: Tringali C (ed) Bioactive compounds from natural sources: isolation, characterization and biological properties

- Dawaki S, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Ithoi I, Ibrahim J, Atroosh WM, Abdulsalam AM, Ahmed A. Is Nigeria winning the battle against malaria? Prevalence, risk factors and KAP assessment among Hausa communities in Kano State. Malar J. 2016;15(1):351. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquis P, Consolo D, Magnin G, Pointaire P, Moretto P, Ynsa MD, Chauffert B. High intra-abdominal pressure enhances the penetration and antitumor effect of intraperitoneal cisplatin on experimental peritoneal carcinomatosis. Ann Surg. 2006;244(1):106. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000218089.61635.5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurant C. From bark to weed: the history of artemisinin. Parasite. 2011;18(3):215–218. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2011183215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidock DA, Rosenthal PJ, Croft SL, Brun R, Nwaka S. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(6):509–520. doi: 10.1038/nrd1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebrehiwot S, Shumbahri M, Eyado A, Yohannes T (2019) Phytochemical screening and in vivo antimalarial activity of two traditionally used medicinal plants of Afar region, Ethiopia, against Plasmodium berghei in Swiss Albino mice. J Parasitol Res 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ibukunoluwa MR. In vivo anti-plasmodial activity and histopathological analysis of water and ethanol extracts of a polyherbal antimalarial recipe. J Pharmacogn Phytother. 2017;9(6):87–100. doi: 10.5897/JPP2017.0449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idowu OA, Soniran OT, Ajana O, Aworinde DO. Ethnobotanical survey of antimalarial plants used in Ogun State, Southwest Nigeria. Afr J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;4(2):055–060. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu ET, Ajaegbu HC, Omotayo AI, Aina OO, Otubanjo OA. In vivo anti-plasmodial activities and toxic impacts of lime extract of a combination of Picralima nitida, Alstonia boonei and Gongronema latifolium in mice infected with Chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium berghei. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(4):1262–1270. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i4.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwalokun BA. Enhanced antimalarial effects of chloroquine by aqueous Vernonia amygdalina leaf extract in mice infected with chloroquine resistant and sensitive Plasmodium berghei strains. Afr Health Sci. 2008;8(1):25–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyiola OA, Tijani AY, Lateef KM. Antimalarial activity of ethanolic stem bark extract of. Asian J Biol Sci. 2011;4(3):235–243. doi: 10.3923/ajbs.2011.235.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jutamaad NS, Aimon S, Yodhtai T. Toxicological and antimalarial activity of the eurycomalactone and Eurycoma longifolia Jack extracts in mice. Thai J Phytopharmacy. 1998;5(2):14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kalra BS, Chawla S, Gupta P, Valecha N. Screening of antimalarial drugs: an overview. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(1):5. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.19846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby GC, O'Neill MJ, Phillipson JD, Warhurst DC. In vittro studies on the mode of action of quassinoids with activity against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38(24):4367–4374. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longdet IY, Adoga EA (2017) Effect of methanolic leaf extract of Carica papaya on Plasmodium berghei infection in albino mice. Eur J Med Plants 1–7

- Lorke D. A new approach to practical acute toxicity testing. Arch Toxicol. 1983;54(4):275–287. doi: 10.1007/BF01234480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martey ONK, Shittah-Bay O, Owusu J, Okine LKN. The antiplasmodial activity of an herbal antimalarial, AM 207 in Plasmodium berghei-infected Balb/c Mice: absence of organ specific toxicity. J Med Sci. 2013;13(7):537–545. doi: 10.3923/jms.2013.537.545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard D, et al. Global analysis of Plasmodium falciparumNa+/H+ exchanger (pfnhe-1) allele polymorphism and its usefulness as a marker of in vitro resistance to quinine. Int J Parasitol. 2013;3:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah MLK, Komlaga G, Forkuo AD, Firempong C, Anning AK, Dickson RA (2019) Toxicity and safety implications of herbal medicines used in Africa, Herbal Medicine, Philip F. Builders, IntechOpen

- Mesia GK, Tona GL, Penge O, Lusakibanza M, Nanga TM, Cimanga RK, Apers S (2005) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moronkeji A, Eze GI, Igunbor MC, Ogbonna AA, Moronkeji AI. Histomorphological and biochemical evaluation of herbal cocktail used in treating malaria on kidneys of adult wistar rats. IJARP. 2019;3(7):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Njan AA (2012) Herbal medicine in the treatment of malaria: vernonia amygdalina: an overview of evidence and pharmacology. Tox Drug Test 167–186

- Nwabuisi C. Prophylactic effect of multi-herbal extract ‘Agbo-Iba'on Malaria induced in mice. East Afr Med J. 2002;79(7):343–346. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i7.8836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofori-Attah K, Oseni LA, Quasie O, Antwi S, Tandoh M (2012) A comparative evaluation of in vivo antiplasmodial activity of aqueous leaf exracts of Carica papaya, Azadirachta indica, Magnifera indica and the combination thereof using plasmodium infected balb/c mice

- Ogbole EA, Ogbole Y, Peter JY, Builders MI, Aguiyi JC. Phytochemical screening and in vivo antiplasmodial sensitivity study of locally cultivated artemisia annua leaf extract against Plasmodium berghei. Am J Ethnomed. 2014;1(1):42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ojurongbe O, Ojo JA, Adefokun DI, Abiodun OO, Odewale G, Awe EO. In vivo antimalarial activities of Russelia equisetiformis in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2015;77(4):504. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.164787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okon OE, Gboeloh LB, Udoh SE. Antimalarial effect of combined extracts of the leaf of Ficus exasperata and stem bark of Anthocleista vogelii on mice experimentally infected with Plasmodium berghei Berghei (Nk 65) Res J Med Plant. 2014;8(3):99–111. doi: 10.3923/rjmp.2014.99.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okpe O, Habila N, Ikwebe J, Upev VA, Okoduwa SI, Isaac OT (2016) Antimalarial potential of Carica papaya and vernonia amygdalina in mice infected with Plasmodium berghei. J Trop Med 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Oladipo OO, Wellington OA, Sutherland CJ. Persistence of chloroquine-resistant haplotypes of Plasmodium falciparum in children with uncomplicated Malaria in Lagos, Nigeria, four years after change of chloroquine as first-line antimalarial medicine. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:41. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0276-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omagha R, Idowu ET, Alimba CG, Otubanjo AO, Agbaje EO, Ajaegbu HCN. Physicochemical and phytochemical screening of six plants commonly used in the treatment of malaria in Nigeria. J Phytomed Therap. 2020;19(2):483–501. doi: 10.4314/jopat.v19i2.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omagha R, Idowu ET, Alimba CG, Otubanjo AO, Adeneye AK. Survey of ethnobotanical cocktails commonly used in the treatment of malaria in southwestern Nigeria. Future J Pharm Sci. 2021;7:152. doi: 10.1186/s43094-021-00298-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omoya FO. The in vivo assessment of antiplasmodial activities of leaves and stem bark extracts of Mangifera indica (linn) and Cola nitida (linn) Int J Infect Dis. 2016;45:373. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onifade OF, Maganda V. In vivo activity of ethanolic extract of Alstonia boonei leaves against Plasmodium berghei in Mice. J Worldwide Holistic Sustain Dev. 2015;1(4):60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Orabueze COI, Sunday AA, Duncan OA, Herbert CA (2018) In vivo antiplasmodial activities of four Nigerian plants used singly and in polyherbal combination against Plasmodium berghei infection

- Peters W. Drug resistance in Plasmodium bergheiVincke and Lips, 1948. I. Chloroquine resistance. Exp Parasitol. 1965;17(1):80–89. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(65)90012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipson JD, Wright CW. Antiprotozoal compounds from plants sources. Planta Med. 1991;57:553–559. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryley JF, Peters W. The antimalarial activity of some quinone esters. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1970;84:209–222. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1970.11686683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udeh MU, Agbaji AS, Williams IS, Ehinmidu P, Ekpa E, Dakare M. Screening for antimicrobial potentials of Azadirachta indica seed oil and essential oil from Cymbopogoncitratus and Eucalyptus citriodora leaves, Nigerian. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;16:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wells TN, Van Huijsduijnen RH, Van Voorhis WC. Malaria medicines: a glass half full? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14(6):424. doi: 10.1038/nrd4573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (2001) Antimalarial drug combination therapy: report of a WHO Technical Consultation. World Health Organization, Geneva. WHO/CDS/RBM/2001.35

- World Health Organisation (2011) World malaria report. Geneva, Switzerland

- World Health Organisation . World malaria report. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation . World malaria report. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Antimalarial drug combination therapy: report of a WHO technical consultation. Geneva: Switzerland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2006) Malaria vector control and personal protection: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series 936. Geneva: WHO [PubMed]

- World Health Organization . Malaria elimination: a field manual for low and moderate endemic countries. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Drug resistance threatens malaria control. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014) Policy brief on malaria diagnostics in low-transmission settings. Geneva

- World Health Organization . Eliminating malaria. Geneva: WHO; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zeleke G, Kebebe D, Mulisa E, Gashe F (2017) In vivo antimalarial activity of the solvent fractions of fruit rind and root of Carica papaya Linn (Caricaceae) against Plasmodium berghei in mice. J Parasitol Res 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]