Abstract

The ground and excited electronic states of the diatomic molecules CaCs and CaNa have been investigated by implementing the ab initio CASSCF/(MRCI + Q) calculation. The potential energy curves of the doublet and quartet electronic low energy states in the representation 2s+1Λ(±) have been determined for the two considered molecules, in addition to the spectroscopic constants Te, ωe, Be, Re, and the values of the dipole moment μe and the dissociation energy De. The determination of vibrational constants Ev, Bv, Dv, and the turning points Rmin and Rmax up to the vibrational level v = 100 was possible with the use of the canonical functions schemes. Additionally, the transition and the static dipole moments curves, Einstein coefficients, the spontaneous radiative lifetime, the emission oscillator strength, and the Franck–Condon factors are computed. These calculations showed that the molecule CaCs is a good candidate for Doppler laser cooling with an intermediate state. A “four laser” cooling scheme is presented, along with the values of Doppler limit temperature TD = 55.9 μK and the recoil temperature Tr = 132 nK. These results should provide a good reference for experimental spectroscopic and ultra-cold molecular physics studies.

Introduction

The discovery of Bose–Einstein condensates1,2 and Fermi gases3 encouraged researchers to study ultra-cold molecules. More specifically, ultra-polar molecules are of high interest as they exhibit a permanent dipole moment that results from the difference in electronegativity between the atoms, leading to an anisotropic continuing dipole–dipole interaction4 in ultra-cold systems. The importance of ultra-cold polar molecules is that they allow the study of modulated chemical reactions5,6 and render descriptive quantum computing and quantum reproduction of lattice spin versions7 possible. In addition, they help in the study of experimental preparation of few-body quantum effects8 and accurate measurements of the variation of the fine structure constant α,9 the proton-to electron mass ratio μ ≡ mp/me,10−14 and the electron dipole moment.15,16 The mixing of an alkali (AK) atom with an alkaline earth (AKE) atom produces an AK–alkaline earth (AK–AKE) molecule with one unpaired electron, which is a polar molecule that has a magnetic dipole moment in the 2Σ+ ground state. We chose to study the (AK–AKE) molecule because its constituents were cooled precisely, and corresponding quantum degenerate systems were already created.17−20 To obtain such a molecule, one can hold two laser-cooled atoms by photoassociation21 or Feshbach resonance.22,23 Our team recently proposed the (AK–AKE) molecule, CaK, as a potential laser-cooling candidate through the Doppler cooling technique.24 Although theoretical studies have been published about some (AK–AKE) molecules such as CsSr,25 MgCs,26 BaCs,27 CaK, CaNa, CaRb,28 and CaLi,29 there are still data that are missing.

This paper has two aims: the first is to fill the missing gap related to the complete absence of theoretical and experimental data on the molecule CaCs and some higher electronic states of the CaNa molecule. The second aim is to investigate whether either of the two molecules could be cooled down to ultra-cold temperatures using the Doppler laser-cooling technique. Consequently, in this work, the electronic structure of these two molecules has been studied using the ab initio CASSCF/(MRCI + Q) method. The potential energy curves (P.E.C.s), the spectroscopic constants Te, ωe, Be, Re, and the static and transition dipole moments (T.D.M.s) have been calculated along with rovibrational constants Ev, Bv, Dv, and the turning points Rmin and Rmax. The calculation of the Franck–Condon factor, the radiative lifetime, the vibrational branching ratio, the Doppler limit temperature TD, the recoil temperature Tr prove the candidacy of the molecule CaCs only for Doppler laser cooling.

In exploring the practicality of laser cooling of these molecules, we have found that the CaCs molecule is an appropriate candidate for Doppler laser cooling where a laser-cooling scheme is presented.

Computational Approach

The basic measurements and calculations are performed in the C2v point-group symmetry with the help of the computational program MOLPRO,30 taking advantage of the graphical user interface GABEDIT.31 The calculations executed by this program have high accuracy due to the analysis of the electron correlation problem. The calculations for the ground and excited states of the CaCs and CaNa molecules are based on the ab initio methods by using the state averaged complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) followed by the multireference configuration interaction (MRCI) method with Davidson correction (+Q). The basis set used for the cesium atom is the quasi-relativistic energy-consistent pseudo-potential ECP46MWB. According to this basis set, 46 electrons are considered frozen with the core of the Cs atom, and as a result, we deal with the cesium atom as a system of nine active electrons only. For the calcium atom of the CaCs molecule, we use the cc-pVQZ quadruple-ζ correlation-consistent polarized basis where all the 20 electrons are considered. Consequently, the CaCs molecule is considered a system of 29 electrons, with three valence electrons. For this molecule, the 13 active orbitals in the C2v symmetry are 6σ (Ca: 4s, 4p0, 3d0, 3d ± 2; Cs: 6s, 6p0), 3π (Ca: 4p ± 1, 3d ± 1; Cs: 6p ± 1), 1δ (Ca: 3d ± 2) distributed into the irreducible representation a1, b1, b2, and a2 as [6, 3, 3, 1]. The calcium atom of the CaNa molecule has been treated using the quasi-relativistic energy consistent pseudo-potential ECP10MWB, where 10 electrons were frozen within the core, and the remaining 10 electrons are considered active electrons within the considered molecular orbital. The sodium atom Na is treated in all-electron schemes using the cc-pVQZ basis. Consequently, the CaNa molecule is considered a system of 21 electrons, with three valence electrons. For this molecule, the 15 active orbitals in the C2v symmetry are 8σ (Ca: 4s, 4p0, 3d0, 3d ± 2, 5s; Na: 3s, 3p0, 4s), 3π (Ca: 4p ± 1, 3d ± 1; Na: 3p ± 1), 1δ (Ca: 3d ± 2) distributed into the irreducible representation a1, b1, b2, and a2 as [8, 3, 3, 1]. We used this combination of basis sets for the two molecules due to the successful results obtained by other groups and previously published papers32−35 that used a similar combination of basis sets for AK–AKE compounds. Additionally, and for more accuracy and comparison, we used the perturbation theory (Rayleigh–Schrödinger perturbation theory) RSPT2-rs2 to calculate the spectroscopic constants for some electronic states for CaCs and CaNa molecules. The RSPT2-rs2 calculations have been done using the same basis sets as the MRCI/CASSCF method, considering three valence electrons for the two molecules. By using the same methods and computing packages, we have also calculated the lowest-lying molecular curves of the CaNa molecule using Aug-cc-pVQZ for the Na atom.

Results and Discussion

Potential Energy Curves

In this work, we draw the P.E.C.s for 25 doublet and quartet low-energy electronic states for the CaCs molecule and 32 doublet and quartet electronic states for the CaNa molecule as a function of the internuclear distance shown in Figures 1–8.

Figure 1.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 2Σ+ and 2Δ electronic states of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 8.

P.E.C.s of the lowest 4Π electronic states of the CaNa molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

The kind of forces holding the atoms specify and control the shape of the obtained curve. Shallow wells are obtained for some electronic states when the repulsive forces overcome the attractive ones within the considered range of internuclear distance.

The cesium and the sodium atoms have an unpaired electron; therefore, they will remain in the doublet state, while the calcium atom Ca exists either in the singlet or in the triplet state. Since the combination of a doublet alkali metal atom with a singlet lowest state of alkaline earth metal results in a doublet state of the molecule, X2Σ+ is the ground state of the two molecules CaCs and CaNa. Now, the combination between the doublet state of Cs and Na atoms with the triplet state of a Ca atom results in the quartet states 4Σ+ of the two molecules.

The P.E.C.s of the doublet electronic states of the CaCs molecule are shown in Figure 1 (2Σ+ and 2Δ electronic states) and Figure 3 (2Π electronic states). The P.E.C.s of the quartet states of the CaCs molecule are shown in Figure 2 (4Σ(±) and 4Δ electronic states) and Figure 4 (4Π electronic states). The P.E.C.s of the doublet electronic states of the CaNa molecule are shown in Figure 5 (2Σ+ and 2Δ electronic states) and Figure 7 (2Π electronic states). The P.E.C.s of the quartet states of the CaNa molecule are shown in Figure 6 (4Σ(±) and 4Δ electronic states) and Figure 8 (4Π electronic states). The P.E.C.s for the molecule CaNa obtained with the Aug-cc-pVQZ basis sets for the Na atom are displayed in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 2Π electronic states of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 2.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 4Σ(±) and 4Δ electronic states of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 4.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 4Π electronic states of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 5.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 2Σ+ and 2Δ electronic states of the CaNa molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 7.

P.E.C.s of the lowest 2Π electronic states of the CaNa molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 6.

P.E.C.s of the lowest 4Σ(±) and 4Δ electronic states of the CaNa molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Table 1 presents the lowest dissociation limits of the calculated low-lying electronic states of the two molecules CaCs and CaNa compared to the combination of atomic orbital values obtained from the National Institute of Standards and Technology website (NIST).36 As a result of the fluctuations and oscillations in the P.E.C at the long-range of the internuclear distance R, the dissociation limits of some of the higher excited molecular states are not achieved, and consequently, these higher molecular states are not considered. A good clarification of these fluctuations in the P.E.C is the Born–Oppenheimer approximation breakdown. The comparison of the dissociation limits of the investigated P.E.C with those obtained with the NIST database agrees well with a relative difference of 14% for the first dissociation limit and 10.9% for the second of the CaCs molecule. For the molecule CaNa, a good agreement is also attained between the values of the dissociation limits obtained with NIST and our calculated values with a relative difference of 0.38 < ΔDe/De < 8.35, except for the fourth dissociation limit where the relative difference is 19.64%. The corresponding values of the dissociation energies De are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 1. Lowest Dissociation Limits of CaCs and CaNa Molecules.

| dissociation of atomic levels Ca + Cs | dissociation energy limit of CaCs levels (cm–1) | molecular states of CaCs | total dissociation energy limit of Ca + Cs atoms (cm–1) | relative error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca (3p64s2, 1S) + Cs (5p66s, 2S) | 0a | X2Σ+ | 0b | 0.0 |

| Ca (3p64s2, 1S) + Cs (5p66p, 2P0) | 9832a | (2)2Σ+, (1)2Π | 11 455b | 14 |

| Ca (3p64s4p, 3P0) + Cs (5p66s, 2S) | 13 561a | (2)2Π, (3)2Σ+, (1)4Π, (1)4Σ+ | 15 228b | 10.9 |

| configuration of Ca + Na | dissociation energy limit of CaNa levels (cm–1) | molecular states of CaNa | total dissociation energy limit of Ca + Na atoms (cm–1) | relative error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca (3p64s2, 1S) + Na (2p63s, 2S) | 0.00a | X2Σ+ | 0.00b | 0.00 |

| Ca (3p64s4p, 3P0) + Na (2p63s, 2S) | 13 891.6a | (2)2Σ+, (1)2Π, (1)4Σ+, (1)4Π | 15 157.9b | 8.35 |

| Ca (3p64s2, 1S) + Na (2p63p, 2P0) | 15 908.2a | (3)2Σ+, (2)2Π | 16 956.1b | 6.18 |

| Ca (3p64s4p, 1P0) + Na (2p63s, 2S) | 23 744.1a | (4)2Σ+, (3)2Π | 23 652.3b | 0.38 |

| Ca (3p63d4s, 3D) + Na (2p63s, 2S) | 25 307.4a | (5)2Σ+, (6)2Σ+, (4)2Π, (1)2Δ, (2)4Σ+, (7)2Σ+, (2)4Π, (2)2Δ, (1)4Δ | 20 335.3b | 19.64 |

| Ca (3p64s4p, 3P0) + Na (2p63p, 2P0) | 29 922.8a | (3)4Σ+, (3)4Π, (1)2Σ–, (3)2Δ, (4)4Σ+, (4)4Π, (1)4Σ–, (2)4Δ | 32 114.0b | 6.82 |

| Ca (3p64s6s, 3S) + Na (2p63s, 2S) | 37 737.3a | (2)4Σ– | 40 474.2b | 6.76 |

Present work.

Experimental data from the NIST atomic spectra database.

Table 2. Spectroscopic Parameters for the X2Σ+ and 13 Excited States of the CaCs Molecule.

| states (2s+1Λ) | method | Te (cm–1) | ΔTe/Te % | Re (Å) | ΔRe/Re % | ωe (cm–1) | Δωe/ωe % | Be (cm–1) | ΔBe/Be % | De (cm–1) | |μe| (au) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2Σ+ | MRCI | 0 | 4.978 | +3.6 | 41.44 | –23.9 | 0.0221 | –6.8 | 894.192 | 3.762 | |

| perturbation | 0 | 5.156 | 31.52 | 0.0206 | |||||||

| (1)2Π | MRCI | 4034.09 | +8.2 | 4.254 | –0.3 | 84.00 | +1.9 | 0.0302 | +0.7 | 6691.755 | 11.222 |

| perturbation | 4366.76 | 4.240 | 85.62 | 0.0304 | |||||||

| (2)2Σ+ | MRCI | 6824.70 | +6.9 | 4.899 | +0.08 | 59.37 | +3.9 | 0.0228 | 0.0 | 3890.082 | 4.189 |

| perturbation | 7295.34 | 4.903 | 61.68 | 0.0228 | |||||||

| (2)2Π | MRCI | 10 912.00 | +1.8 | 4.990 | +2.5 | 41.38 | –7.7 | 0.0220 | –5.0 | 3545.286 | 2.779 |

| perturbation | 11 110.40 | 5.113 | 38.17 | 0.0209 | |||||||

| (1)4Π | MRCI | 11 855.64 | +1.0 | 4.711 | +1.2 | 60.39 | –6.0 | 0.0248 | –2.8 | 2600.873 | 9.495 |

| perturbation | 11 970.20 | 4.767 | 56.79 | 0.0241 | |||||||

| (4)2Σ+ | MRCI | 13 624.61 | +13.4 | 4.802 | –4.3 | 78.07 | +26.9 | 0.0237 | +9.3 | 6994.970 | 0.482 |

| perturbation | 15 458.38 | 4.596 | 99.04 | 0.0259 | |||||||

| (1)2Δ | MRCI | 14 747.09 | +5.7 | 4.200 | –0.4 | 81.19 | +2.7 | 0.0310 | +1.0 | 9382.437 | 11.967 |

| perturbation | 15 586.57 | 4.183 | 83.42 | 0.0313 | |||||||

| (3)2Π | MRCI | 14 819.56 | +7.5 | 4.516 | +0.4 | 67.55 | –14 | 0.0268 | –3.0 | 6104.507 | 6.275 |

| perturbation | 15 928.58 | 4.589 | 58.08 | 0.0260 | |||||||

| (1)4Δ | MRCI | 14 987.06 | +5.36 | 4.077 | +0.2 | 82.63 | +12.5 | 0.0329 | –0.3 | 9174.208 | 10.343 |

| perturbation | 15 790.82 | 4.086 | 92.94 | 0.0328 | |||||||

| (4)2Π | MRCI | 17 737.17 | +2.0 | 5.204 | –2.8 | 57.06 | +13.7 | 0.0202 | +6.0 | 6503.924 | 1.307 |

| perturbation | 18 092.90 | 5.056 | 64.91 | 0.0214 | |||||||

| (2)4Π | MRCI | 19 238.21 | +0.08 | 5.412 | –0.6 | 40.12 | +14 | 0.0187 | +1.1 | 4886.337 | 2.304 |

| perturbation | 19 254.39 | 5.379 | 45.75 | 0.0189 | |||||||

| (3)4Π | MRCI | 21 112.83 | +1.2 | 5.154 | +3.5 | 48.97 | –1.5 | 0.0206 | –5.8 | 3130.329 | 5.347 |

| perturbation | 21 370.67 | 5.334 | 48.23 | 0.0194 | |||||||

| (5)2Π | MRCI | 22 048.66 | +0.8 | 4.857 | +5.9 | 55.01 | –23.3 | 0.0232 | –10.8 | 2232.292 | 1.929 |

| perturbation | 22 226.51 | 5.142 | 42.20 | 0.0207 | |||||||

| (1)4Σ– | MRCI | 22 747.93 | +2.0 | 4.911 | +10.7 | 36.86 | –33.0 | 0.0227 | –18.5 | 1540.725 | 7.521 |

| perturbation | 23 197.12 | 5.437 | 24.69 | 0.0185 |

Table 3. Spectroscopic Parameters for the X2Σ+ and 26 Excited States of the CaNa Molecule (Na Atom: cc-pVQZ and aug-cc-pVQZ).

| states Λ2s+1 | method [reference] | Te (cm–1) | ΔTe/Te % | Re (Å) | ΔRe/Re % | ωe (cm–1) | Δωe/ωe % | Be (cm–1) | ΔBe /Be % | De (cm–1) | ΔDe/De % | |μe| (au) | Δμe/μe % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis)[this work] | 0.00 | 3.759 | 101.3 | 0.0817 | 1721 | 1.38 | ||||||

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 0.00 | 3.749 | 0.3 | 103.4 | 2.1 | 0.0821 | 0.5 | ||||||

| perturbation [this work] | 3.851 | 2.4 | 91.8 | 9.4 | 0.0778 | 4.8 | |||||||

| CASSCF/MRCI36 | 3.670 | 2.3 | 103.0 | 1.6 | 0.0830 | 1792 | 3.9 | 1.18 | 14.5 | ||||

| CCSD(T)27 | 3.720 | 1.0 | 97.0 | 4.2 | 1.5 | 1453 | 15.5 | 1.01 | 26.8 | ||||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 3.665 | 2.5 | 103.0 | 1.6 | 1802 | 4.4 | 1.17 | 15.2 | |||||

| CASPT237 | 3.666 | 2.4 | 102.6 | 1.2 | 1752 | 1.7 | 1.09 | 21.0 | |||||

| CCSD37 | 3.720 | 1.0 | 88.5 | 12.6 | 1264 | 26.5 | |||||||

| (1)2Π | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis)[this work] | 6572.57 | 2.6 | 3.323 | 0.00 | 164.4 | 0.7 | 0.1045 | 0.00 | 9034 | 12.0 | 2.85 | 20.0 |

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 6401.98 | 3.6 | 3.323 | 0.69 | 163.3 | 2.6 | 0.1045 | 1.3 | 10 275 | 11.4 | 2.28 | 18.9 | |

| perturbation [this work] | 6807.73 | 3.6 | 3.346 | 2.97 | 160.1 | 4.5 | 0.1031 | 10 199 | 3.4 | 2.31 | |||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 6825 | 4.0 | 3.224 | 2.94 | 172.2 | 4.5 | 9360 | ||||||

| CASPT237 | 6851 | 8.8 | 3.225 | 2.25 | 172.2 | 6.1 | |||||||

| CCSD37 | 7211 | 3.248 | 175.1 | ||||||||||

| (2)2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 9374.00 | 0.3 | 3.919 | 0.2 | 119.8 | 0.4 | 0.0751 | 0.4 | 6226 | 8.6 | 0.99 | 45.4 |

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 9344.73 | 1.1 | 3.927 | 0.7 | 120.3 | 1.2 | 0.0748 | 1.5 | 6815 | 7.3 | 0.54 | 1.0 | |

| perturbation [this work] | 9472.78 | 8.6 | 3.948 | 3.1 | 118.4 | 3.8 | 0.0740 | 6721 | 2.4 | 0.98 | |||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 10 261 | 9.0 | 3.795 | 3.0 | 124.6 | 4.0 | 6076 | ||||||

| CASPT237 | 10 305 | 10.4 | 3.800 | 5.6 | 124.9 | 7.9 | |||||||

| CCSD37 | 10 472 | 3.696 | 130.1 | ||||||||||

| (1)4Π | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 13 065.21 | 1.5 | 3.734 | 1.34 | 109.7 | 6.6 | 0.0828 | 2.6 | 2515 | 11.1 | 3.08 | 19.5 |

| perturbation [this work] | 12 872.69 | 8.2 | 3.784 | 2.75 | 102.4 | 2.9 | 0.08060 | 2832 | 10.1 | 2.48 | 19.8 | ||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 14 238 | 8.1 | 3.631 | 2.78 | 113.0 | 3.0 | 2800 | 0.9 | 2.47 | ||||

| CASPT237 | 14 220 | 6.6 | 3.630 | 2.46 | 113.1 | 0.7 | 2540 | ||||||

| CCSD37 | 13 998 | 3.64 | 110.5 | ||||||||||

| (2)2Π | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 13 708.69 | 0.7 | 3.570 | 0.14 | 124.2 | 2.1 | 0.0905 | 0.4 | 3920 | 21.6 | 3.25 | 29.5 |

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 13 611.21 | 2.7 | 3.565 | 3.00 | 126.8 | 9.5 | 0.0909 | 5.7 | 5003 | 17.8 | 4.61 | 16.9 | |

| perturbation [this work] | 14 080.64 | 0.5 | 3.677 | 4.98 | 112.4 | 11.6 | 0.0853 | 4773 | 14.2 | 3.91 | |||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 13 786 | 1.8 | 3.392 | 4.92 | 140.6 | 11.4 | 4573 | ||||||

| CASPT237 | 13 966 | 0.1 | 3.394 | 7.31 | 140.3 | 15.1 | |||||||

| CCSD37 | 13 688 | 3.309 | 146.4 | ||||||||||

| (3)2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 13 894.96 | 0.3 | 4.065 | 0.54 | 100.5 | 2.7 | 0.0699 | 0.8 | 3682 | 11.9 | 0.52 | 30.8 |

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 13 849.72 | 1.9 | 4.043 | 2.36 | 97.8 | 16.7 | 0.0705 | 4.7 | 4180 | 10.0 | 0.36 | 3.9 | |

| perturbation [this work] | 14 162.47 | 4.7 | 4.161 | 4.32 | 117.3 | 8.0 | 0.0666 | 4094 | 7.3 | 0.50 | |||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 14 585 | 4.9 | 3.889 | 4.37 | 92.4 | 4.9 | 3413 | ||||||

| CASPT237 | 14 622 | 6.2 | 3.887 | 6.10 | 95.1 | 22.2 | |||||||

| CCSD37 | 14 814 | 3.817 | 78.1 | ||||||||||

| (1)4Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 15 390.75 | 4.4 | 6.041 | 7.2 | 22.9 | 12.2 | 0.0316 | 14.2 | 176 | 25.7 | 1.67 | 3.0 |

| perturbation [this work] | 14 708.90 | 8.2 | 6.474 | 4.9 | 25.7 | 4.5 | 0.0271 | 237 | 29.8 | 1.62 | 4.8 | ||

| CASSCF/MRCI36 | 16 775 | 8.2 | 5.740 | 5.0 | 24.0 | 3.3 | 251 | 12.0 | 1.59 | 10.1 | |||

| CASSCF/MRCI37 | 16 775 | 5.5 | 5.735 | 3.3 | 23.7 | 4.8 | 200 | 14.5 | 1.50 | ||||

| CASPT237 | 16 288 | 5.838 | 2.6 | 21.8 | 7.4 | 206 | |||||||

| CCSD37 | 5.882 | 21.2 | |||||||||||

| (4)2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 17 800.28 | 3.588 | 156.5 | 0.0897 | 7665 | 0.03 | ||||||

| (1)4Σ– | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 20 017.54 | 0.3 | 3.221 | 0.6 | 162.3 | 2.5 | 0.1111 | 1.1 | 11 463 | 1.27 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 20 086.76 | 3.241 | 166.4 | 0.1099 | |||||||||

| (3)2Π | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 21 289.08 | 2.5 | 3.754 | 0.6 | 114.4 | 5.1 | 0.0819 | 1.2 | 4227 | 4.85 | ||

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 20 755.62 | 3.775 | 108.5 | 0.0809 | |||||||||

| (4)2Π | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 21 670.05 | 0.5 | 3.761 | 0.6 | 82.3 | 5.1 | 0.0816 | 0.9 | 5311 | 2.65 | ||

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 21 561.58 | 3.737 | 86.5 | 0.0823 | |||||||||

| (5)2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 22 223.91 | 3.726 | 117.1 | 0.0832 | 4692 | 4.04 | ||||||

| (2)4Π | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 22 242.86 | 0.1 | 4.037 | 1.3 | 107.0 | 1.9 | 0.0709 | 2.7 | 4792 | 2.36 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 22 266.68 | 4.089 | 105.0 | 0.0690 | |||||||||

| (2)4Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 23 797.06 | 0.2 | 3.964 | 3.9 | 92.4 | 17.0 | 0.0734 | 7.3 | 3183 | 4.17 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 23 847.03 | 4.119 | 76.7 | 0.0680 | |||||||||

| (6)2Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 24 767.42 | 3.926 | 39.5 | 0.0744 | 2169 | 12.27 | ||||||

| (3)4Π | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 25 841.54 | 0.3 | 4.222 | 3.0 | 74.8 | 6.9 | 0.0648 | 5.8 | 5428 | 1.36 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 25 771.95 | 4.348 | 69.6 | 0.06104 | |||||||||

| (2)2Δ | CASSCF/MRCI (Na: cc-pVQZ basis) [this work] | 26 034.51 | 1.6 | 3.978 | 3.4 | 64.0 | 28.3 | 0.0730 | 7.0 | 915 | 3.61 | ||

| CASSCF/MRCI (Na: Aug-cc-pVQZ) [this work] | 25 605.11 | 3.842 | 82.1 | 0.0781 | |||||||||

| (1)4Δ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 26 267.05 | 4.355 | 45.3 | 0.0608 | 789 | 2.24 | ||||||

| (3)2Δ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 28 307.45 | 3.616 | 121.3 | 0.0883 | 3251 | 0.77 | ||||||

| (2)4Δ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 29 435.36 | 0.5 | 3.634 | 0.2 | 142.0 | 6.5 | 0.0874 | 0.3 | 2103 | 1.83 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 29 595.75 | 3.628 | 132.8 | 0.0877 | |||||||||

| (4)4Π 2nd min | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 29 554.57 | 4.626 | 56.3 | 0.0540 | 1921 | 4.43 | ||||||

| (4)4Π 1st min | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 29 652.33 | 3.412 | 148.0 | 0.0991 | 1761 | 0.55 | ||||||

| (3)4Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 29 914.75 | 1.2 | 3.610 | 3.5 | 105.0 | 6.3 | 0.0886 | 6.8 | 1584 | 1.74 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 30 268.02 | 3.738 | 98.4 | 0.0826 | |||||||||

| (1)4Φ | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 30 830.53 | 3.267 | 171.5 | 0.1073 | 0.92 | |||||||

| (4)4Σ+ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 31 135.44 | 4.6 | 4.027 | 3.5 | 114.1 | 31.0 | 0.0712 | 6.9 | 492 | 2.97 | ||

| perturbation [this work] | 32 584.45 | 4.170 | 78.7 | 0.0663 | |||||||||

| (2)2Σ– | CASSCF/MRCI [this work] | 32 086.31 | 0.7 | 3.687 | 0.7 | 106.0 | 15.5 | 0.0850 | 1.5 | 1.97 | |||

| perturbation [this work] | 32 299.26 | 3.713 | 122.4 | 0.0837 | |||||||||

| (5)4Σ+ 1st min | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 33 283.47 | 4.569 | 65.0 | 0.0553 | 7.44 | |||||||

| (5)4Σ+ 2nd min | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 34 600.65 | 8.002 | 88.2 | 0.0168 | 11.67 | |||||||

| (3)4Δ | CASSCF/MRCI[this work] | 35 205.66 | 4.082 | 89.0 | 0.0692 | 5226 | 5.17 |

In Figures 1–8, one can notice some shallow potential energy wells, which are the evidence of the dominant Coulomb repulsive forces over the attractive ones. In these figures, for the two considered molecules, the avoided crossings that occur between the adiabatic states are the results of an interplay between the ionic state and all other states. Crossings are also generated due to the strong repulsive behavior of the electronic states. The positions of crossing and avoided crossing are provided in Table S1 in the Supporting Information with their corresponding energy gaps ΔE. As a result, the appearance of a barrier potential and multiple wells are due to the avoided crossing behavior corresponding to a crossing in the diabatic picture.

Spectroscopic Parameters

The spectroscopic constants ωe, Re, Be, Te, and De of the two molecules CaCs and CaNa electronic states have been calculated by fitting the P.E.C values around the minimum of the internuclear distance Re to a polynomial in terms of R. These constants are obtained by using CASSCF/MRCI and perturbation RSPT2-rs2 methods for 14 electronic states of the molecule CaCs and 27 electronic states for the molecule CaNa. They are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. For the molecule CaCs, no comparison can be made between our calculated values and those of the literature since they are presented here for the first time. However, there is an important agreement between the results we obtained using CASSCF/MRCI and RSPT2-rs2 methods.

Our calculated equilibrium bond distance Re and harmonic frequency ωe for the ground state X2Σ+ of the CaNa molecule overlap well with those in the three references,28,37,38 with relative differences of 1% ≤ ΔRe/Re ≤ 2.5% and 1.2% ≤ Δωe/ωe ≤ 4.2%, respectively, except for a larger relative difference Δωe/ωe = 10.5%38 calculated by using the CCSD method. Our calculated value of Be is very close to that calculated by Gopakumar et al.28 with a relative difference ΔBe/Be = 1.5%.

For the excited states, our values of Te compare well with those in the literature for seven excited electronic states, where the relative differences vary as 0.1%(2)2Π38 < ΔTe/Te < 10.4%(2)2∑+.38 Similarly, the internuclear distance Re also shows a very good agreement when compared with published data, with a relative difference of 2.25%38 ≤ ΔRe/Re ≤ 7.31%.38 The comparison of our results with the values of ωe obtained by different techniques in the literature shows a good agreement with the relative difference of 7%(1)4Π38 ≤ Δωe/ωe ≤ 1.6%(1)2Π.38 The comparison of our calculated values of ωe with those obtained by using the CCSD method38 shows a relative difference of 22.2%. There is no comparison for the other investigated states since they are calculated here first.

The comparison of our calculated values of the spectroscopic constants by using the Aug-cc-pVQZ basis sets for Na atom in Table 3 with those calculated by using the cc-pVQZ basis set for the same atom shows an excellent agreement with the average relative differences of the ground and the studied excited states ΔTe/Te = 0.97%, ΔRe/Re = 0.29%, Δωe/ωe = 1.32%, and Δωe/ωe = 0.52%. Given these values, we estimate that the use of the diffuse Gaussian basis functions (aug-) for the Na atom has no real effect on the investigated data of the molecule CaNa.

The absence of spectroscopic constants of some electronic states is referred to the presence of avoided crossing near the minima of these states. As a verification of the accuracy of our results given in Tables 2 and 3, the trend of the spectroscopic constants is presented in Table 4, where Te, ωe, and Be decrease for each electronic state with the decrease of the electronegativity and Re increases as we go from CaNa to CaCs.

Table 4. Study of the Trend of the Spectroscopic Constants of the Different Electronic States of the Molecules CaNa and CaCs.

Permanent Dipole Moment

The permanent dipole moment of a diatomic molecule is an important parameter since it clarifies the type of bonding (ionic/covalent) and the polarity of a given molecular interaction. As stated in the Introduction, the importance of polar ultra-cold molecules lies in using long-life interactions among their permanent dipole moments in specific applications. We have estimated the dipole moment curves (D.M.C.s), representing the molecular permanent dipole moment variation with the internuclear distance R, for the 25 lowest doublet and quartet electronic states of CaCs and the 32 lowest doublet and quartet electronic states of the CaNa molecule. These curves are plotted in the Supporting Information, in Figures S2–S9. The electron density distribution controls the values of the dipole moments. The geometry of the investigated systems is such that the calcium atom is chosen to be at the origin for both CaNa and CaCs molecules. Consequently, a charge transfer from Ca to Cs and from Ca to Na leads to negative dipole moment values when the charge density is closer to the Cs and Na atoms. This polarity is indicated as Caδ+Csδ− and Caδ+Naδ− for CaCs and CaNa molecules, respectively.

The permanent dipole moment (PDM) curves for the ground state X2Σ+ of the two molecules CaCs and CaNa are positive with maximum values |μe| = 1.78 au at R = 4.14 Å and |μe| = 0.691 au at R = 2.92 Å, respectively. The curves reach zero at a large distance (R = 10 Å), indicating the molecule’s breaking into a neutral fragment. The absolute values of μe were calculated for both molecules’ ground and excited states and are tabulated in Tables 2 and 3. It should be noted here that the abrupt gradient change of the PDM curves is due to the occurrence of an avoided crossing between the P.E.C.s of two states of the same symmetry. The positions of the avoided crossings concur with those of the D.M.C. polarity shifts.

The comparison of our calculated PDM(μe) values for the ground state (X)2∑+ of the molecule CaNa shows an almost acceptable agreement with the values present in the literature with a relative error 14.5%37 ≤ Δμe/μe ≤ 21%.38 The first excited quartet state (1)4∑– shows a good agreement with a relative error 3%37 ≤ Δμe/μe ≤ 10.1%.38 The comparison of our calculated values of (μe) for the excited states (1)2Π, (2)2∑+, (1)4Π, (2)2Π, (3)2∑+ with those published by Pototschnig et al.38 shows an acceptable agreement with a relative error 1% ≤ Δμe/μe ≤ 19.8%. The exception goes when the calculations were performed by using the ab initio CASPT2 method, with a relative error 19.5% ≤ Δμe/μe ≤ 45.4%.

Transition Dipole Moment Curves and Radiative Lifetimes

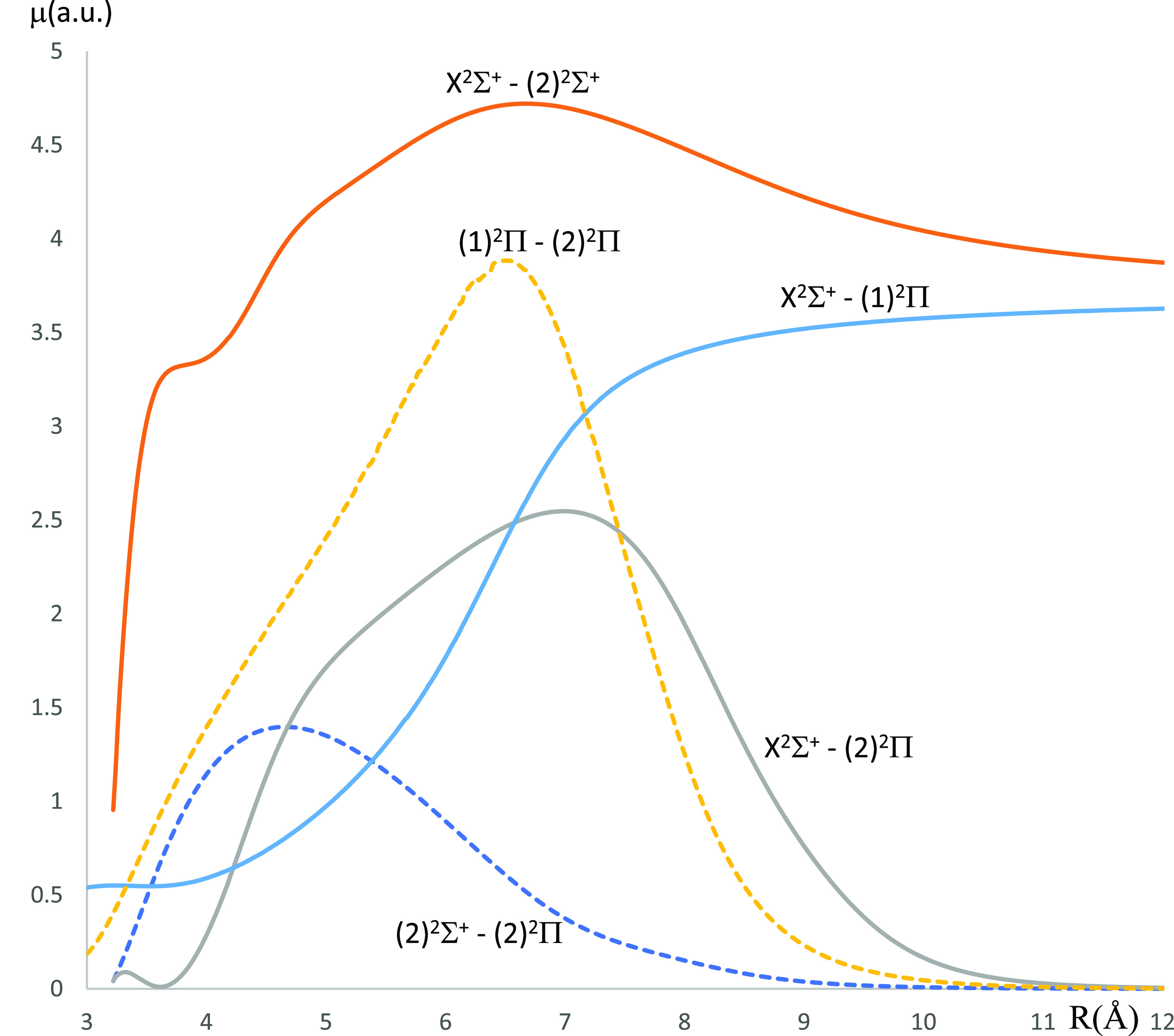

The T.D.M. is useful for predicting the possible transitions that are likely to occur between certain electronic states. In our work, we investigated and show in Figures 9 and 10 the transition dipole moment curves (TDMCs) of the allowed transitions from the lowest excited to the ground X2Σ+ states for the molecules CaCs and CaNa as a function of the internuclear distance.

Figure 9.

Transition D.M.C.s between the ground state X2Σ+ and the lowest-excited doublet states of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

Figure 10.

Transition D.M.C.s between the ground state X2Σ+ and the lowest-excited doublet states of the CaNa molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

For the molecule CaCs, the TDMCs for the transitions X2Σ+–(2)2Π, (1)2Π–(2)2Π, and (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π vanish when R is larger than 10.5 Å where the occurrence of these

transitions

is at a very low probability. For the two transitions X2Σ+–(1)2Π and X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, the

transitions are maximal for R greater than 11 and

5.54 Å, respectively. The TDMCs for the X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, X2Σ+–(1)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, and (1)2Π–(2)2Π transitions of the CaNa molecule vanish when R is larger than 9 Å. The transition X2Σ+–(2)2Π is the highest for R greater than 16 Å. We have considered the T.D.M.

values at the equilibrium position Re of

the upper state for each electronic transition to calculate the emission

coefficients proposed by Hilborn39 for

the two considered molecules, CaCs and CaNa. The T.D.M. value|μ21| and the radiative lifetime τ21 ( where j runs for the underlying

states of the i state), the emission angular frequency

ω21, the Einstein coefficients of spontaneous emissions A21, the oscillator strength constant |f21|, and the classical radiative decay rate

of the single-electron oscillator γcl are presented

in Table 5. The emission

coefficients for the allowed electronic transitions are given below,

where νij is the transition frequency

between the two states, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity,

and me is the mass of an electron

where j runs for the underlying

states of the i state), the emission angular frequency

ω21, the Einstein coefficients of spontaneous emissions A21, the oscillator strength constant |f21|, and the classical radiative decay rate

of the single-electron oscillator γcl are presented

in Table 5. The emission

coefficients for the allowed electronic transitions are given below,

where νij is the transition frequency

between the two states, ε0 is the vacuum permittivity,

and me is the mass of an electron

| 1.1 |

| 1.2 |

| 1.3 |

| 1.4 |

Table 5. Transition Dipole Moment Values of the Upper State at its Equilibrium Position |μ|, the Emission Angular Frequency ω21, the Einstein Spontaneous Coefficients A21, the Spontaneous Radiative Lifetime τspon, the Classical Radiative Decay Rate of the Single-Electron Oscillator γcl, and the Emission Oscillator Strength f21 of Some Transitions among the Doublet States of CaCs and CaNa Molecules.

| transition | |μ21| (au) | ω21 × 10–15 (rad s–1) | A21 (s–1) | τ21 (ns) | γcl × 10–6 (s–1) | |f21| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaCs | ||||||

| X2Σ+–(1)2Π | 0.655 | 0.760 | 56 934.23 | 17 564.12 | 3.61 | 0.00526 |

| X2Σ+–(2)2Π | 1.698 | 2.055 | 7 573 195.06 | 132.04 | 26.41 | 0.09557 |

| (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π | 1.355 | 0.768 | 253 461.85 | 3945.37 | 3.70 | 0.02280 |

| (1)2Π–(2)2Π | 2.386 | 1.295 | 3 743 637.51 | 267.12 | 10.49 | 0.11893 |

| X2Σ+–(3)2Σ+ | 2.471 | 2.343 | 23 763 471.39 | 42.08 | 34.32 | 0.23078 |

| X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+ | 4.595 | 1.286 | 13 572 618.85 | 73.68 | 10.33 | 0.43783 |

| CaNa | ||||||

| X2Σ+–(1)2Π | 0.037 | 1.238 | 769.05 | 1 300 317.3 | 9.57 | 0.000027 |

| X2Σ+–(2)2Π | 1.018 | 2.581 | 5 389 790.30 | 185.6 | 41.65 | 0.043144 |

| (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π | 0.159 | 0.817 | 4120.94 | 242 666.3 | 4.17 | 0.000329 |

| (1)2Π–(2)2Π | 0.968 | 1.344 | 686 368.83 | 1456.7 | 11.29 | 0.020275 |

| X2Σ+–(3)2Σ+ | 3.881 | 2.616 | 81 540 743.90 | 12.3 | 42.79 | 0.635332 |

| X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+ | 1.668 | 1.765 | 4 621 351.20 | 216.4 | 19.48 | 0.079116 |

The comparison of our data with previous work is absent since it is calculated here for the first time.

The oscillator strength expresses the probability of absorption or emission of electromagnetic radiation in transitions between energy levels of a molecule. If an emissive state has a small oscillator strength, nonradiative decay will outpace radiative decay. Conversely, “bright” transitions will have large oscillator strengths. From Table 5, we found that the largest oscillator strength belongs to the (X)2Σ+–(3)2Σ+ transition of the molecule CaNa and the most considerable value of the radiative lifetime is for the transition (X)2Σ+–(1)2Π of the same molecule. Since we are interested in the transition (X)2Σ+–(1)2Π for the laser cooling of the molecule CaCs, one can notice that the oscillator strength of this molecule is larger than that of the molecule CaNa, while the radiative lifetime is shorter. With these two conditions, the molecule CaCs is more advantageous for experimental laser cooling than the molecule CaNa.

Vibration–Rotation Calculation

The vibrational energy Ev, the rotational constant Bv, and the centrifugal distortion constant Dv for the ground and many excited electronic states of the CaCs and CaNa molecules are determined by using the canonical functions approach40,41 and the cubic spline interpolation between each two consecutive points of the P.E.C obtained from the ab initio calculation of the molecule. Then, the calculated vibrational eigenvalues of energy and the P.E.C of the investigated states are used to determine the abscissas of the turning points Rmin and Rmax for each vibrational level. The calculations were done for a large number of vibrational levels up to v = 100 for deep well potential, while few vibrational levels were calculated for shallow well potentials. However, these calculations cannot be achieved for some electronic states due to crossings and avoided crossing in the P.E.C near the minima, the existence of double minima, and for very shallow potentials.

The vibrational constants of the investigated electronic states of the two molecules CaCs and CaNa are collected and presented in Tables S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information. There is no comparison with other data for the ground and the excited states of the molecules CaCs since they are investigated here for the first time. For the ground state (Χ)2∑+ of the CaNa molecule, the rotational constants Bv of five vibrational levels have been found in the literature. The comparison of our calculated values of these constants with those given in the literature shows a very good agreement with the relative difference 0.02%28 ≤ ΔBv/Bv ≤ 2.2%.28 The comparison for the other vibrational constants of the investigated electronic states of the molecule CaNa is absent since they are calculated here for the first time. These theoretical data will be a good guide for the spectroscopic experimentalists, particularly the values of Rmin and Rmax that will be compared with the values of the experimental Rydberg–Klein–Rees potentials.

Laser-Cooling Study

Laser-Cooling Viability of CaCs Molecule

The small difference in equilibrium positions ΔRe between the two electronic X2Σ+ and (2)2Σ+ states and X2Σ+ and (2)2Π states of the CaCs molecule directed our attention to study the laser-cooling feasibility for this molecule. The primary criteria for direct laser cooling is a highly diagonal Franck–Condon factors (FCFs) between the ground and a low-lying excited electronic state. This allows the use of a limited number of lasers to keep the molecule in a closed-loop cycle.42 The second criterion that affects a molecule’s laser-cooling viability is a short radiative lifetime between the vibrational levels of the involved electronic states. In the present work, a direct laser cooling is studied between the two electronic X2Σ+ and (2)2Π states in the presence of the intervening electronic states (1)2Π and (2)2Σ+ between them.

An examination of the table of the spectroscopic constants of the CaNa molecule shows a large difference between the values of the internuclear distance at equilibrium Re for the ground electronic state and that of higher excited states. Such a large difference usually implies a non-diagonal FCF between the involved states. Consequently, we aborted further investigations of CaNa laser cooling at this stage.

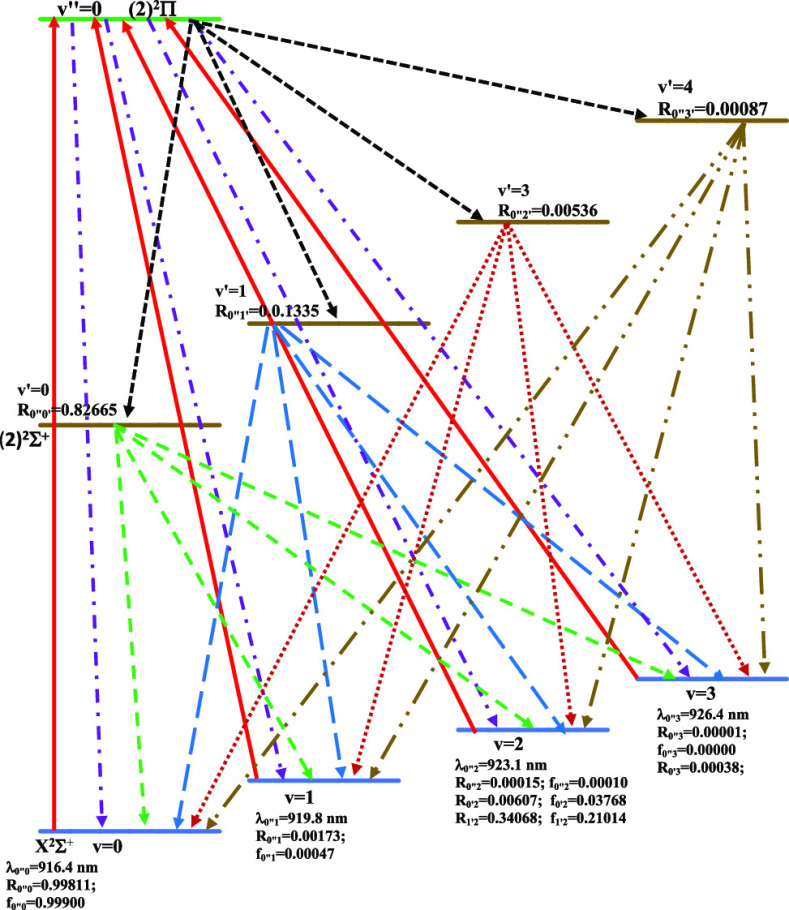

By using the LEVEL 11 program,43 we have calculated the FCFs for the transitions X2Σ+–(1)2Π, X2Σ+–(2)2Π, X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, (1)2Π–(2)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(1)2Π of the CaCs molecule at the vibrational levels 0 ≤ v″ ≤ 5 of the upper states (2)2Π and 0 ≤ v ≤ 5 of the lower states X2Σ+. The graphical representation of the FCF for the cited transitions is shown in Figure 11, and their corresponding values are set in Table S4 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 11.

FCF plotting for the transitions (a) (2)2Σ+–X2Σ+, (b) (2)2Π(2)–2Σ+, (c) X2Σ+–(2)2Π, (d) (2)2Σ+–(1)2Π, (e) (2)2Π–(1)2Π, and (f) X2Σ+–(1)2Π of the CaCs molecule using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons.

We can notice by checking Figure 11c and the values in Table S5 in the Supporting Information that the FCFs for the six lowest vibrational levels of the transition (2)2Π → X2Σ+ of the molecule CaCs are diagonal (f00 = 0.998, f11 = 0.999, f22 = 0.998, f33 = 0.991, f44 = 0.972, and f55 = 0.935). This diagonal nature has also been proven experimentally and theoretically.28,38,44 Based on these values of FCFs, we study the direct laser cooling for this transition (2)2Π → X2Σ+. The intermediate state (1)2Π has no effect on the cycling cooling of this transition since the FCFs for the transitions (2)2Σ+–(1)2Π, X2Σ+–(1)2Π, and (2)2Π–(1)2Π shown in Figure 11d–f, respectively, are minimal for the lowest vibrational levels. The intermediate (2)2Σ+ state cannot be ignored since the FCFs for the transitions X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+ (Figure 11a) and (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π (Figure 11b) are significant for the first three vibrational levels. The laser cooling of molecules with a non-intervening intermediate electronic state between the cycling levels has been confirmed for several molecules, with specific requirements.42−46 These include a higher transition probability and a smaller radiative lifetime for transitions between the electronic excited and the ground states than the intermediate one. Completing these criteria would assure that an intermediate state does not hinder the laser-cooling cycle. Recently, however, Yuan et al.,47 Nguyen and Odom,48 and Li et al.49 have proposed laser-cooling schemes involving intervening electronic intermediate states in the cooling cycle. In the following, we show that within the approximation of spin-free calculations, the CaCs molecule is suitable for laser cooling through the cycle X2Σ+–(2)2Π with the involvement of the intermediate state (2)2Σ+ in the laser-cooling process.

To apply a three-step cooling scheme, one has to investigate the radiative lifetime, the value of the FCFs, and vibrational loss ratio between the ground, excited, and intervening states. We denote by v the vibrational states belonging to the ground state X2Σ+, ν′ are the ones belonging to the intermediate state (2)2Σ+, and ν″ belongs to the excited states involved in the cooling loop (2)2Π. To obtain the values of the radiative lifetime τ, the LEVEL program can be used to calculate the Einstein coefficients42 of the ro–vibrational transitions through the formula45

| 2 |

μ(r) is the electronic T.D.M. (in debye),46Aν″ν is the Einstein coefficient in s–1, ΔE is the emission frequency (in cm–1), J is the rotational quantum number, and S(J′, J″) is the Hönl–London factor whose values vary with the nature of the electronic transition. The present version of the program calculates A only in the case of singlet–singlet transitions. Given that the states we are dealing with are doublets, we will be using the following vibrational approximation instead (consider Λ as the projection of the angular momentum of an electronic state on the internuclear axis). For the parallel transitions with ΔΛ = 0, such as the transition X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, we use

| 3 |

For the perpendicular transitions with ΔΛ = ±1, such as X2Σ+–(2)2Π and (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, the recommended definition of the perpendicular T.D.M.50 is usually represented by

| 4.1 |

| 4.2 |

In the present work, however, we used the T.D.M. functions in MOLPRO software as μx, μy, and μz where the calculated T.D.M. is vertical (given with respect to x, y, and z). In this case, the Einstein coefficients50 are divided by 2 and given by

| 5 |

The calculated values of the radiative

lifetime  for the transitions

X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, (2)2Π–(2)2Σ+, and X2Σ+––(2)2Π are given

in Table 5. We find

a strong correspondence between the value of τ among electronic

transitions (calculated in Table 5) and the vibrational state transitions τ0 (Table 6).

More specifically, for the transitions X2Σ+–(2)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, and X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, the electronic transition

radiative lifetimes τ are 132.04, 3945.37, and 73.68 ns, respectively;

the values of τ0 for the same transitions are 136.5,

4050, and 71.8 ns. The highly diagonal FCF (Table S5) for the transition X2Σ+–(2)2Π (Figure 11c) and the short value of the radiative lifetime 68.3 <

τ0 < 71.4 ns are indicative of a possible laser-cooling

scheme involving these two states.

for the transitions

X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, (2)2Π–(2)2Σ+, and X2Σ+––(2)2Π are given

in Table 5. We find

a strong correspondence between the value of τ among electronic

transitions (calculated in Table 5) and the vibrational state transitions τ0 (Table 6).

More specifically, for the transitions X2Σ+–(2)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, and X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, the electronic transition

radiative lifetimes τ are 132.04, 3945.37, and 73.68 ns, respectively;

the values of τ0 for the same transitions are 136.5,

4050, and 71.8 ns. The highly diagonal FCF (Table S5) for the transition X2Σ+–(2)2Π (Figure 11c) and the short value of the radiative lifetime 68.3 <

τ0 < 71.4 ns are indicative of a possible laser-cooling

scheme involving these two states.

Table 6. Radiative Lifetimes τ of the Vibrational Transitions between the Electronic States X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, X2Σ+–(2)2Π, and (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π of the CaCs Molecule.

| X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | ν′(22Σ+) = 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| ν (X2Σ+) = 0 | Avv′ | 1.151437 × 107 | 1.962532 × 106 | 5.683341 × 105 | 1.114800 × 105 | 2.341589 × 104 | 4.344481 × 103 | 8.972812 × 102 |

| Rvv′ | 8.266503 × 10–1 | 1.400070 × 10–1 | 4.046544 × 10–2 | 7.914280 × 10–3 | 1.868120 × 10–3 | 7.091100 × 10–4 | 1.613200 × 10–4 | |

| 1 | Avv′ | 2.317422 × 106 | 6.674955 × 106 | 3.148351 × 106 | 1.573059 × 106 | 4.793907 × 105 | 1.421461 × 105 | 3.500623 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 1.663744 × 10–1 | 4.761911 × 10–1 | 2.241629 × 10–1 | 1.116759 × 10–1 | 3.824573 × 10–2 | 2.320121 × 10–2 | 6.293740 × 10–3 | |

| 2 | Avv′ | 8.454822 × 104 | 4.775409 × 106 | 2.473803 × 106 | 2.889758 × 106 | 2.520671 × 106 | 1.148000 × 106 | 4.570333 × 105 |

| Rvv′ | 6.069960 × 10–3 | 3.406776 × 10–1 | 1.761350 × 10–1 | 2.051521 × 10–1 | 2.010988 × 10–1 | 1.873776 × 10–1 | 8.216958 × 10–2 | |

| 3 | Avv′ | 5.354361 × 103 | 5.721896 × 105 | 6.013017 × 106 | 2.735225 × 105 | 1.570320 × 106 | 2.758580 × 106 | 1.884728 × 106 |

| Rvv′ | 3.844000 × 10–4 | 4.081999 × 10–2 | 4.281274 × 10–1 | 1.941813 × 10–2 | 1.252799 × 10–1 | 4.502579 × 10–1 | 3.388535 × 10–1 | |

| 4 | Avv′ | 6.403610 × 103 | 4.299750 × 10–1 | 1.752144 × 106 | 5.339973 × 106 | 1.515287 × 105 | 2.990324 × 105 | 1.983343 × 106 |

| Rvv′ | 4.597300 × 10–4 | 3.000000 × 10–8 | 1.247528 × 10–1 | 3.790998 × 10–1 | 1.208894 × 10–2 | 4.880833 × 10–2 | 3.565834 × 10–1 | |

| 5 | Avv′ | 8.483919 × 102 | 2.365979 × 104 | 5.973875 × 104 | 3.435269 × 106 | 3.099584 × 106 | 9.225905 × 105 | 6.341689 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 6.091000 × 10–5 | 1.687890 × 10–3 | 4.253410 × 10–3 | 2.438794 × 10–1 | 2.472844 × 10–1 | 1.505860 × 10–1 | 1.140166 × 10–2 | |

| 6 | Avv′ | 3.535833 × 100 | 8.639941 × 103 | 2.953637 × 104 | 4.628698 × 105 | 4.689579 × 106 | 8.519738 × 105 | 1.137650 × 106 |

| Rvv′ | 2.500000 × 10–7 | 6.163700 × 10–4 | 2.102990 × 10–3 | 3.286043 × 10–2 | 3.741340 × 10–1 | 1.390599 × 10–1 | 2.045370 × 10–1 | |

| sum (s–1) = Aν′ν | 1.392895 × 107 | 1.401739 × 107 | 1.404492 × 107 | 1.408593 × 107 | 1.253449 × 107 | 6.126667 × 106 | 5.562074 × 106 | |

| τ (s) = 1/Aν′ν | 7.180000 × 10–8 | 7.130000 × 10–8 | 7.120000 × 10–8 | 7.100000 × 10–8 | 7.980000 × 10–8 | 1.630000 × 10–7 | 1.800000 × 10–7 | |

| τ (ns) | 71.8 | 71.3 | 71.2 | 71.0 | 79.8 | 1163.0 | 180.0 | |

| value | ν′(2)2Π = 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2Σ+–(2)2Π | ||||||||

| ν(X2Σ+) = 0 | Avv′ | 7.307537 × 106 | 1.540002 × 101 | 4.043620 × 102 | 9.457135 × 101 | 6.757200 × 100 | 3.648095 × 10–1 | 7.106915 × 10–1 |

| Rvv′ | 9.653976 × 10–1 | 2.020432 × 10–6 | 2.680556 × 10–5 | 6.233773 × 10–6 | 4.440631 × 10–7 | 2.398561 × 10–8 | 5.021044 × 10–8 | |

| 1 | Avv′ | 1.264076 × 104 | 7.364731 × 106 | 5.969834 × 103 | 1.797929 × 103 | 2.045633 × 102 | 1.655454 × 101 | 1.930394 × 100 |

| Rvv′ | 1.669969 × 10–3 | 9.662287 × 10–1 | 3.957462 × 10–4 | 1.185124 × 10–4 | 1.344329 × 10–5 | 1.088433 × 10–6 | 1.363826 × 10–7 | |

| 2 | Avv′ | 2.258488 × 103 | 1.027514 × 104 | 1.483069 × 107 | 6.272968 × 104 | 9.686437 × 103 | 1.250687 × 103 | 3.088913 × 101 |

| Rvv′ | 2.983685 × 10–4 | 1.348065 × 10–3 | 9.831410 × 10–1 | 4.134895 × 10–3 | 6.365639 × 10–4 | 8.223058 × 10–5 | 2.182321 × 10–6 | |

| 3 | Avv′ | 1.413538 × 102 | 8.786911 × 103 | 4.521870 × 101 | 1.482928 × 107 | 1.908601 × 105 | 2.434150 × 104 | 3.637003 × 103 |

| Rvv′ | 1.867423 × 10–5 | 1.152814 × 10–3 | 2.997592 × 10–6 | 9.774880 × 10–1 | 1.254276 × 10–2 | 1.600413 × 10–3 | 2.569547 × 10–4 | |

| 4 | Avv′ | 2.742864 × 101 | 9.229474 × 101 | 1.918221 × 104 | 3.223685 × 104 | 1.462070 × 107 | 4.422058 × 105 | 5.720593 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 3.623594 × 10–6 | 1.210877 × 10–5 | 1.271608 × 10–3 | 2.124927 × 10–3 | 9.608291 × 10–1 | 2.907429 × 10–2 | 4.041606 × 10–3 | |

| 5 | Avv′ | 5.826010 × 10–1 | 9.546542 × 101 | 3.824662 × 101 | 3.266196 × 104 | 1.738525 × 105 | 1.409420 × 107 | 8.486087 × 105 |

| Rvv′ | 7.696734 × 10–8 | 1.252475 × 10–5 | 2.535406 × 10–6 | 2.152948 × 10–3 | 1.142507 × 10–2 | 9.266697 × 10–1 | 5.995431 × 10–2 | |

| 6 | Avv′ | 2.285418 × 100 | 5.437355 × 100 | 2.191561 × 102 | 1.304577 × 101 | 4.475723 × 104 | 5.057950 × 105 | 1.310403 × 107 |

| Rvv′ | 3.019262 × 10–7 | 7.133633 × 10–7 | 1.452808 × 10–5 | 8.599260 × 10–7 | 2.941312 × 10–3 | 3.325517 × 10–2 | 9.258013 × 10–1 | |

| sum (s–1) = Aν′ν | 7.322607 × 106 | 7.384002 × 106 | 1.485655 × 107 | 1.495881 × 107 | 1.504007 × 107 | 1.506780 × 107 | 1.401352 × 107 | |

| τ (s) = 1/Aν′ν | 1.365634 × 10–7 | 1.354279 × 10–7 | 6.731039 × 10–8 | 6.685022 × 10–8 | 6.648906 × 10–8 | 6.636667 × 10–8 | 7.135968 × 10–8 | |

| τ (ns) | 136.6 | 135.4 | 67.3 | 66.8 | 66.5 | 66.4 | 71.3 | |

| (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π | ||||||||

| ν((2)2Σ+) = 0 | Avv′ | 2.040594 × 105 | 5.247195 × 104 | 2.665403 × 103 | 7.337515 × 101 | 1.493461 × 102 | 2.015362 × 101 | 1.837800 × 10–2 |

| Rvv′ | 8.266518 × 10–1 | 2.203419 × 10–1 | 1.166686 × 10–2 | 3.461200 × 10–4 | 8.452600 × 10–4 | 1.422200 × 10–4 | 1.300000 × 10–7 | |

| 1 | Avv′ | 3.296895 × 104 | 1.129200 × 105 | 9.423539 × 104 | 1.278708 × 104 | 3.367380 × 10–1 | 5.392491 × 102 | 1.804288 × 102 |

| Rvv′ | 1.335584 × 10–1 | 4.741772 × 10–1 | 4.124822 × 10–1 | 6.031886 × 10–2 | 1.900000 × 10–6 | 3.805360 × 10–3 | 1.281980 × 10–3 | |

| 2 | Avv′ | 8.250505 × 103 | 4.673072 × 104 | 4.538750 × 104 | 1.132751 × 105 | 3.195216 × 104 | 6.208191 × 102 | 8.950309 × 102 |

| Rvv′ | 3.342308 × 10–2 | 1.962331 × 10–1 | 1.986678 × 10–1 | 5.343382 × 10–1 | 1.808413 × 10–1 | 4.380990 × 10–3 | 6.359380 × 10–3 | |

| 3 | Avv′ | 1.322416 × 103 | 1.992522 × 104 | 4.203309 × 104 | 9.110008 × 103 | 1.057596 × 105 | 5.718606 × 104 | 4.353858 × 103 |

| Rvv′ | 5.357150 × 10–3 | 8.367061 × 10–2 | 1.839850 × 10–1 | 4.297348 × 10–2 | 5.985731 × 10–1 | 4.035497 × 10–1 | 3.093507 × 10–2 | |

| 4 | Avv′ | 2.140005 × 102 | 4.777781 × 103 | 3.043745 × 104 | 2.584151 × 104 | 1.445372 × 101 | 7.736191 × 104 | 8.060838 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 8.669200 × 10–4 | 2.006301 × 10–2 | 1.332292 × 10–1 | 1.218989 × 10–1 | 8.180000 × 10–5 | 5.459263 × 10–1 | 5.727394 × 10–1 | |

| 5 | Avv′ | 2.971031 × 101 | 1.110592 × 103 | 1.048777 × 104 | 3.421640 × 104 | 9.297499 × 103 | 5.397876 × 103 | 4.271001 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 1.203600 × 10–4 | 4.663630 × 10–3 | 4.590651 × 10–2 | 1.614047 × 10–1 | 5.262153 × 10–2 | 3.809165 × 10–2 | 3.034636 × 10–1 | |

| 6 | Avv′ | 5.437040 × 100 | 2.024822 × 102 | 3.212693 × 103 | 1.668792 × 104 | 2.951271 × 104 | 5.815654 × 102 | 1.199406 × 104 |

| Rvv′ | 2.202000 × 10–5 | 8.502700 × 10–4 | 1.406243 × 10–2 | 7.871980 × 10–2 | 1.670346 × 10–1 | 4.103980 × 10–3 | 8.522031 × 10–2 | |

| sum (s–1) = Aν′ν | 2.468505 × 105 | 2.381388 × 105 | 2.284593 × 105 | 2.119914 × 105 | 1.766862 × 105 | 1.417076 × 105 | 1.407418 × 105 | |

| τ (s) = 1/Aν′ν | 4.050000 × 10–6 | 4.200000 × 10–6 | 4.380000 × 10–6 | 4.720000 × 10–6 | 5.660000 × 10–6 | 7.060000 × 10–6 | 7.110000 × 10–6 | |

| τ (μs) | 4.05 | 4.22 | 4.38 | 4.72 | 5.66 | 7.06 | 7.11 | |

From the calculated Einstein coefficients, we additionally calculate the vibrational branching ratios by taking onto account the intermediate state for the three transitions using the following formulas51,52

| 6.1 |

| 6.2 |

| 6.3 |

The obtained values are given in Table 6.

In setting out a laser-cooling scheme, the number of cycles (N) for photon absorption/emission should be maximized to sufficiently decelerate the molecule in the Doppler laser-cooling beams.52,53 The graphical representation of our proposed scheme is shown in Figure 12, where lasers are represented by red solid lines along with their wavelength. The spontaneous decays are represented by dotted lines with the values of their FCF (fν′ν) and the vibrational branching ratios (Rν′ν). The wavelength of the main pumping laser (2)2Π(v″ = 0) ← X2Σ+(ν = 0) is λ0″ = 916.4 nm. Three re-pumping laser beams are employed to avoid leakage to lower vibrational levels. The wavelength of these repumping lasers for the transitions (2)2Π(v″ = 0) ← X2Σ+(ν = 1), (2)2Π(v″ = 0) ← X2Σ+ (ν = 2), and (2)2Π(v″ = 0) ← X2Σ+(ν = 3) are, respectively, λ0″1 = 918.8 nm, λ0″2 = 923.1 nm, and λ0″3 = 926.4 nm. In this case, N, which is the reciprocal to the total loss, is given by

| 7.1 |

where

| 7.2 |

| 7.3 |

| 7.4 |

| 7.8 |

| 7.9 |

Figure 12.

Laser-cooling scheme for the transition X2Σ+–(2)2Π οf the molecule CaCs with the intermediate state (2)2Σ+.

For more experimental detail, the parameters L, amax, V, and T, which are respectively the slowing distance, the maximum acceleration, the initial velocity, and temperature are24,52

| 8.1 |

| 8.2 |

| 8.3 |

| 8.4 |

where Kb and h are the Boltzmann and Planck constants and m is the mass of the considered CaCs molecule.

With this value of N, the experimental parameters given in eq 4.2 are V = 15.16 m/s, amax = 7.37 × 103 m/s2, and L = 1.56 cm. We have considered the ratio of the number of excited states connected to the ground state in the main cycling transition (Ne) to the number of ground states connected to the excited state of the leading cycling transition (Ntot) plus Ne. We have approximated the value of Ne/Ntot = 1/5 by only taking into account the vibrational ground and excited states and ignoring any hyperfine structure. The value of the slowing distance L can be considered as a convenient choice as it is within the range of the experimental values for a typical laser cooling setup. By using the calculated experimental parameters of eq 4.2V = 15.19 m/s, Tini = 2.51 K and amax = 7.37 × 103, we find that the Doppler and Recoil temperatures that can be reached during the cooling process are24,54

| 9 |

The molecule’s initial velocity and temperature imply that one needs to find a cooling process that would lead to the initial temperature of 2.51 K before it reaches the nanokelvin regime. Buffer gas cooling is a flexible method that is applicable to a multitude of molecules. It consists of thermalizing species through collisions with a cold buffer gas, whose role is to dissipate the molecules’ translational energy. Buffer gas cooling of calcium-bearing molecules has been proven successful for species such as CaH, which were cooled to temperatures close to microkelvin.

We model the CaCs molecules to be produced through a typical laser ablation technique before being driven into a buffer cooling cell, to be then sent in the Doppler laser-cooling setup. According to the hard-sphere collision model, after N collisions in the buffer gas cell, the molecules are thermalized to the temperature TN, which is given by52

| 10 |

We consider the initial temperature Ti = 7000 K as the typical temperature of the CaCs molecules as they leave the laser ablation setup, TB = 2 K is the initial temperature of the helium gas in the buffer gas cell, and TN = 2.51 K is the precooling temperature of CaCs molecules. From eq 6.1, one can find the number of collisions in the buffer cell N = 224.

For a low density of CaCs molecules, the average distance λ (mean free path) covered by the molecules between N and N – 1 collisions with the helium gas of the buffer cell is given by52

| 11 |

At a low helium density of nHe = 5 × 1014 atom/cm3 and at low temperature, the scattering cross-sectional value for collisions between CaCs molecules and He atoms is typically close to σX–He = 10–14 cm2, leading to a value of λ = 0.0295 cm. By using the rules of the kinetic theory of ideal gases, the time for thermalizing the molecules of the CaCs in the buffer cell is then given by24

| 12 |

where KB is the

Boltzmann constant and  .

.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have reported ab initio

calculations of 25 doublet

and quartet states of the CaCs molecule and 32 doublet and quartet

low-lying energy states of the CaNa molecule. We studied the P.E.C.s

and D.M.C.s of these molecules with three valence electrons at the

spin-free level by using the CASSCF/MRCI method with the basis sets

ECP46MWB and ECP10MWB for Cs and Ca atoms, respectively, while for

the Na atom, we used the two basis aug-ccpVAZ and ccpVAZ. In addition,

the PDMs for the ground and the excited electronic states have been

calculated and for most of the bound states, the spectroscopic constants Te, ωe, Be, Re, and De have been also obtained. Moreover, the ro-vibrational constants Ev, Bv, and Dv with the abscissas of turning points Rmin and Rmax have

been obtained for different vibrational levels of the ground state

and some low-lying electronic states of the two molecules by means

of the canonical function approach. The T.D.M.s have been also determined

for the lowest electronic transitions, along with the emission angular

frequency ω21 and the oscillator strength f21. The calculation of the FCF, the Einstein

coefficients  , and

the spontaneous radiative lifetime

for the molecule CaCs shows its candidacy for a direct laser cooling

between the two electronic states X2Σ+ and (2)2Π. The study of this cooling has been done

with the intermediate states (1)2Π and (2)2Σ+ by calculating the vibrational branching ratios,

the number of cycles (N) for photon absorption/emission,

the experimental parameters of this cooling, and the recoil and Doppler

temperatures. The values of the initial required temperature show

the need for a precooling buffer gas cell, in a typical experimental

setup. A laser cooling scheme is presented with four pumping and repumping

lasers whose wavelengths are in the infrared region. These results

open the way for an experimental work on the cooling of the transition

X2Σ+–(2)2Π of

the CaCs molecule, with an intermediate state. Cooling polar molecules

such as CaCs to the microkelvin and nanokelvin range of temperature

could lead to phenomena and discoveries far beyond the focus of traditional

molecular science. More precisely, such studies offer promising applications

such as new platforms for quantum computing, precise control of molecular

dynamics, nanolithography, and Bose–Einstein condensate of

a polar molecule. The electric dipole–dipole interaction may

give rise to a molecular superfluid via Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer

pairing, and it leads to fundamentally new condensed-matter phases

and new complex quantum dynamics.55

, and

the spontaneous radiative lifetime

for the molecule CaCs shows its candidacy for a direct laser cooling

between the two electronic states X2Σ+ and (2)2Π. The study of this cooling has been done

with the intermediate states (1)2Π and (2)2Σ+ by calculating the vibrational branching ratios,

the number of cycles (N) for photon absorption/emission,

the experimental parameters of this cooling, and the recoil and Doppler

temperatures. The values of the initial required temperature show

the need for a precooling buffer gas cell, in a typical experimental

setup. A laser cooling scheme is presented with four pumping and repumping

lasers whose wavelengths are in the infrared region. These results

open the way for an experimental work on the cooling of the transition

X2Σ+–(2)2Π of

the CaCs molecule, with an intermediate state. Cooling polar molecules

such as CaCs to the microkelvin and nanokelvin range of temperature

could lead to phenomena and discoveries far beyond the focus of traditional

molecular science. More precisely, such studies offer promising applications

such as new platforms for quantum computing, precise control of molecular

dynamics, nanolithography, and Bose–Einstein condensate of

a polar molecule. The electric dipole–dipole interaction may

give rise to a molecular superfluid via Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer

pairing, and it leads to fundamentally new condensed-matter phases

and new complex quantum dynamics.55

Acknowledgments

This publication is based upon work supported by the Khalifa University of Science and Technology under award no. CIRA-2019-054. The authors would like to acknowledge the use of the Al MISBAR high-power computer for the completion of their work. N.E.-K. is partly supported by the internal grant (8474000336-KU-SPSC), Space and Planetary Science Center, Khalifa University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c01224.

Potential energy curves of the lowest 2Σ+, 2Π, and 2Δ electronic states of the CaNa molecule with the Aug-cc-pVQZ basis for the Na atom using the CASSCF/MRCI method with three valence electrons; permanent D.M.C.s of the doublet and quartet states of CaCs and CaNa; position of the crossings Rc and avoided crossing RAC with the energy difference ΔE of the molecule two molecules CaCs and CaNa; vibrational parameters of the excited states of the CaCs and CaNa molecules; and FCF for the lowest transitions X2Σ+–(1)2Π, X2Σ+–(2)2Σ+, (1)2Π–(2)2Π, (2)2Σ+–(2)2Π, and X2Σ+–(2)2Π of the CaCs molecule (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Davis K. B.; Mewes M.-O.; Andrews M. R.; Van Druten N. J.; Durfee D. S.; Kurn D. M.; Ketterle W. Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Gas of Sodium Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 3969–3973. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. H.; Ensher J. R.; Matthews M. R.; Wieman C. E.; Cornell E. A. Observation of Bose-Einstein Condensation in a Dilute Atomic Vapor. Science 1995, 269, 198–201. 10.1126/science.269.5221.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco B.; Jin D. S. Onset of Fermi Degeneracy in a Trapped Atomic Gas. Science 1999, 285, 1703–1706. 10.1126/science.285.5434.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti C.; Lewenstein M.; Lahaye T.; Pfau T.; Campa A.; Giansanti A.; Morigi G.; Labini F. S. Dipolar interaction in ultra-cold atomic gases. AIP Conf. Proc. 2008, 970, 332. 10.1063/1.2839130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan N.; Dalgarno A. Chemistry at ultracold temperatures. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2001, 341, 652–656. 10.1016/S0009-2614(01)00515-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krems R. V. Cold controlled chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 4079–4092. 10.1039/B802322K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheli A.; Brennen G. K.; Zoller P. A toolbox for lattice-spin models with polar molecules. Nat. Phys. 2006, 2, 341–347. 10.1038/nphys287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer T.; Mark M.; Waldburger P.; Danzl J. G.; Chin C.; Engeser B.; Lange A. D.; Pilch K.; Jaakkola A.; Nägerl H.-C.; Grimm R. Evidence for Efimoy quantum states in an ultracold gas of caesium atoms. Nature 2006, 440, 315–318. 10.1038/nature04626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson E. R.; Lewandowski H. J.; Sawyer B. C.; Ye J. Cold Molecule Spectroscopy for Constraining the Evolution of the Fine Structure Constant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 143004. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.143004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flambaum V. V.; Kozlov M. G. Enhanced Sensitivity to the Time Variation of the Fine-Structure Constant and mp/me in Diatomic Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 150801. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.150801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller S. Hydrogenlike Highly Charged Ions for Test of the Time Independence of Fundamental Constants. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 180801. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.180801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelevinsky T.; Kotochigova S.; Ye J. Precision Test of Mass-Ratio Variations with Lattice-Confined Ultracold Molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 043201. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.043201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMille D.; Sainis S.; Sage J.; Bergeman T.; Kotochigova S.; Tiesinga E. Enhanced Sensitivity to Variation of me/mp in Molecular Spectra. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 043202. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.043202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelkovnikov A.; Butcher R. J.; Chardonnet C.; Amy-Klein A. Stability of the Proton-to-Electron Mass Ratio. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 150801. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.150801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson E. R.; Gilfoy N. B.; Kotochigova S.; Sage J. M.; DeMille D. Inelastic Collisions of Ultracold Heteronuclear Molecules in an Optical Trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 203201. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.203201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J. J.; Kara D. M.; Smallman I. J.; Sauer B. E.; Tarbutt M. R.; Hinds E. A. Improved measurement of the shape of the electron. Nature 2011, 473, 493–496. 10.1038/nature10104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett A. J. Bose-Einstein condensation in the alkali gases: Some fundamental concepts. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 307. 10.1103/RevModPhys.73.307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgini S.; Pitaevskii L. P.; Stringari S. Theory of ultracold atomic Fermi gases. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 1215. 10.1103/RevModPhys.80.1215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stellmer S.; Tey M. K.; Huang B.; Grimm R.; Schreck F. Bose-Einstein Condensation of Strontium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 200401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.200401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft S.; Vogt F.; Appel O.; Riehle F.; Sterr U. Bose-Einstein Condensation of Alkaline Earth Atoms: 40Ca. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 130401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.130401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni K.-K.; Ospelkaus S.; De Miranda M. H. G.; Pe’er A.; Neyenhuis B.; Zirbel J. J.; Kotochigova S.; Julienne P. S.; Jin D. S.; Ye J. A high phase-space-density gas of polar molecules. Science 2008, 322, 231. 10.1126/science.1163861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa K.; Akamatsu D.; Hayashi M.; Oasa K.; Kobayashi J.; Naidon P.; Kishimoto T.; Ueda M.; Inouye S. Coherent Transfer of Photoassociated Molecules into the Rovibrational Ground State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 203001. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.203001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr L. D.; DeMille D.; Krems R. V.; Ye J. Cold and Ultracold Molecules: Science, Technology, and Applications. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 055049. 10.1088/1367-2630/11/5/055049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa A.; El-Kork N.; Korek M. Laser Cooling and Electronic Structure Studies ofCaK and Its Ions CaK ±. New J. Phys. 2021, 23, 013017. 10.1088/1367-2630/abd50d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guérout R.; Aymar M.; Dulieu O. Ground state of the polar alkali-metal-atom-strontium molecules: Potential energy curve and permanent dipole moment. J. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 042508. 10.1103/PhysRevA.82.042508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augustovičová L.; Soldán P. Ab initio properties of MgAlk (Alk = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs). J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 136, 084311. 10.1063/1.3690459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou D.; Kuang X.; Gao Y.; Huo D. Theoretical study on the ground state of the polar alkali-metal-barium molecules: Potential energy curve and permanent dipole moment. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142, 034308. 10.1063/1.4906049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopakumar G.; Abe M.; Hada M.; Kajita M. Dipole polarizability of alkali-metal (Na, K, Rb)-alkaline-earth-metal (Ca,Sr) polar molecules: Prospects for alignment. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 224303. 10.1063/1.4881396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krois G.; Pototschnig J. V.; Lackner F.; Ernst W. E. Spectroscopy of Cold LiCa Molecules Formed on Helium Nanodroplets. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 13719–13731. 10.1021/jp407818k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H. J.; Knowles P. J.; Knizia G.; Manby F. R.; Schutz M.; Celani P.; Korona T.; Lindh R.; Mitrushenkov A.; Rauhut G.; Shamasundar K. R.; Adler T. B.; Amos R. D.; Bernhardsson A.; Berning A.; Cooper D. L.; Deegan M. J. O.; Dobbyn A. J.; Eckert F.; Goll E.; Hampel C.; Hesselmann A.; Hetzer G.; Hrenar T.; Jansen G.; Koppl C.; Liu Y.; Lloyd A. W.; Mata R. A.; May A. J.; McNicholas S. J.; Meyer W.; Mura M. E.; Nicklas A.; O’Neill D. P.; Palmieri P.; Peng D.; Pfluger K.; Pitzer R.; Reiher M.; Shiozaki T.; Stoll H.; Stone A. J.; Tarroni R.; Thorsteinsson T.; Wang M.. Version 2010.1, A Package of Ab Initio Programs, 2010. see. http://www.molpro.net/info/users.

- Allouche A.-R. Gabedit-A graphical user interface for computational chemisrty softwares. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 174. 10.1002/jcc.21600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad L.; Chamieh G.; Korek M. Theoretical Electronic Structure with Rovibrational Calculations of Alkali-Beryllium Molecules BeX (X=K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Scr. 2020, 95, 085402. 10.1088/1402-4896/ab9bda. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeid I.; Atallah T.; Kontar S.; Chmaisani W.; El-Kork N.; Korek M. Theoretical Electronic Structure of the Molecules SrX (X= Li, Na, K) toward Laser Cooling Study. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2018, 1126, 16–32. 10.1016/j.comptc.2018.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houalla D.; Chmaisani W.; El-Kork N.; Korek M. Electronic Structure Calculation of the MgAlk (Alk= K, Rb, Cs) Molecules for Laser Cooling Experiments. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2017, 1108, 103–110. 10.1016/j.comptc.2017.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeid I.; Al Abdallah R.; El-Kork N.; Korek M. Ab-initio calculations of the electronic structure of the alkaline earth hydride anions XH– (X = Mg, Ca, Sr and Ba) toward laser cooling experiment. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2020, 224, 117461. 10.1016/j.saa.2019.117461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramida A.; Ralchenko Y.; Reader J.. NIST ASD Team 2018 NIST Atomic Spectra Database. Version 5.6.1; National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2018.

- Pototschnig J. V.; Hauser A. W.; Ernst W. E. Electric dipole moments and chemical bonding of diatomic alkali–alkaline earth molecules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 5964–5973. 10.1039/C5CP06598D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pototschnig J. V.; Meyer R.; Hauser A. W.; Ernst W. E. Vibronic transitions in the alkali-metal (Li, Na, K, Rb) – alkaline-earth-metal (Ca, Sr) series: A systematic analysis of de-excitation mechanisms based on the graphical mapping of Franck-Condon integrals. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 022501. 10.1103/PhysRevA.95.022501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilborn R. C. Einstein coefficients, cross sections, f values, dipole moments, and all that. Am. J. Phys. 1982, 50, 982–986. 10.1119/1.12937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elmoussaoui S.; El-Kork N.; Korek M. Electronic structure of the ZnCl molecule with rovibrational and ionicity studies of the ZnX (X = F, Cl, Br, I) compounds. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2016, 1090, 94–104. 10.1016/j.comptc.2016.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chmaisani W.; El-Kork N.; Elmoussaoui S.; Korek M. Electronic structure calculations with the spin orbit effect of the low-lying electronic states of the YbBr molecule. ACS Omega 20192019, 4, 14987–14995. 10.1021/acsomega.9b01759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa M. D. Laser-cooling molecules. Concept, candidates, and supporting hyperfine-resolved measurements of rotational lines in the A-X(0,0) band of CaH. Eur. Phys. J. D. 2004, 31, 395–402. 10.1140/epjd/e2004-00167-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy R. J.; LEVEL R. J. A Computer Program for Solving the Radial Schrödinger Equation for Bound and Quasibound Levels. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 2017, 186, 167–178. 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2016.05.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerschmann J.; Schwanke E.; Pashov A.; Knöckel H.; Ospelkaus S.; Tiemann E. Laser and Fourier-transform spectroscopy of KCa. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 032505. 10.1103/PhysRevA.96.032505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M.; Huang D.; Shao J.; Yu Y.; Li S.; Li Y. Effects of spin-orbit coupling on laser cooling of BeI and MgI. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 164312. 10.1063/1.4934719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.-S.; Gao Y.-F.; Yu Y.; Gao T. Ab Initio Study of the Feasibility of Laser Cooling of ScO Molecule. Mol. Phys. 2016, 114, 870–875. 10.1080/00268976.2015.1129461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X.; Guo H.-J.; Wang Y.-M.; Xue J.-L.; Xu H.-F.; Yan B. Laser-cooling with an intermediate electronic state : Theoretical prediction on bismuth hydride. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 224305. 10.1063/1.5094367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J. H. V.; Odom B. Prospects for Doppler cooling of three-electronic-level molecules. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 053404. 10.1103/PhysRevA.83.053404. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.-Y.; Yang C.-L.; Sun Z.-P.; Wang M.-S.; Ma X.-G. Theoretical study on the spectroscopic properties of the low-lying electronic states and the laser cooling feasibility of the CaI molecule. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 2021, 270, 107709. 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2021.107709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernath P. F.Spectra of Atoms and Molecules, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: NY, 10016, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lane I. C. Production of ultracold hydrogen and deuterium via Doppler-cooled Feshbach molecules. Phys. Rev. A: At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 2015, 92, 022511. 10.1103/PhysRevA.92.022511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Yuan X.; Liang G.; Wu Y.; Wang J.; Yan B. Laser Cooling of the SiO+ Molecular Ion: A Theoretical Contribution. Chem. Phys. 2019, 525, 110412. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2019.110412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Letokhov V. S.; Minogin V. G.; Pavlik B. D. Cooling and trapping of atoms and molecules by a resonant laser field. J. Opt. Commun. 1976, 19, 72–75. 10.1016/0030-4018(76)90388-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel J. R.; Wang C.; Rodriguez K.; Hemmerling B.; Lewis T. N.; Bardeen C.; Teplukhin A.; Kendrick B. K. Spectroscopy on the X1Σ+ → A1Π Transition of Buffer-Gas Cooled AlCl. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, 012801. 10.1103/PhysRevA.104.012801. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr L. D.; DeMille D.; Krems R. V.; Ye J. Jun Ye, Cold and Ultracold Molecules: Science, Technology, and Applications. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 055049. 10.1088/1367-2630/11/5/055049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.