Abstract

Efficient adsorbents are critical to the purification of liquefied natural gas (LNG) by the adsorption method. In this study, the physiochemical properties of JLOX-500 and 13X were examined. JLOX-500 with more Al content had a more compact unit cell, a larger surface area and pore volume, a smaller average pore size, and more microchannels on the surface than 13X. The separation performance of the two adsorbents was evaluated by the adsorption experiment. The CO2 adsorption capacity of JLOX-500 was higher than that of 13X, while the equilibrium and ideal selectivity and separation factor of CO2/CH4 were also larger for JLOX-500. Especially in dynamic adsorption, the CO2 adsorption capacities at 50 ppm of the gas mixture at the outlet were 3.46 and 1.64 mmol/g for JLOX-500 and 13X, respectively. The adsorption heats of CO2 and CH4 on JLOX-500 were 40.50 and 18.77 kJ/mol, whereas these values were 31.49 and 18.50 kJ/mol for 13X, respectively. A better separation performance for JLOX-500 was observed because of fewer binders and a lower Si/Al ratio (1.34). The Toth adsorption isotherm model described best the experimental data. According to the results of this study, JLOX-500 was a more efficient adsorbent used in purification for LNG production at high pressure with low CO2 concentration.

1. Introduction

Natural gas is generally considered the best bridge fuel between fossil fuels and the renewable energy to cope with the challenges of increasing energy demands and environmental protection.1 To meet the requirements of pipeline transportation, storage, and energy content of the commercial natural gas for the civil and industrial utility, the raw natural gas must be processed to decrease the amount of incombustible gases, especially the removal of CO2 because of the erosion and damage to pipes caused by its acidity.2 The separation and purification technologies for the CO2/CH4 gas mixture generally include absorption, cryogenic distillation, membrane technology, and adsorption.3 Compared with other three methods, adsorption technology is one of the most promising alternative processes for energy-intensive separation, especially in the small scale, with the advantages of a simple process, easy operation requirements, low investment costs, and energy conservation in regeneration.4−7

The CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity of adsorbents are crucial to the adsorption process.8 Zeolites widely used in gas separation have several positive features such as high temperature and pressure stability and low energy consumption in regeneration.9 The adsorption and separation of the zeolites are determined by many elements such as their microstructure, the nature and number of balanced cations, the silicon-to-aluminum (Si/Al) ratio, and so on.10−12 There are more cations in the framework in the case of the lower Si/Al ratio, which are preferred adsorption sites and would enhance the electrostatic field.11,12 Remy et al. compared the performance of Na-KFI having a low Si/Al ratio with ZK-5 having a high Si/Al ratio and reported that the former’s working capacity was larger than that of the latter because of the enhanced electrostatic interaction with the quadrupole moment of CO2, which does not exist in CH4.13 Palomino et al. synthesized a series of LTA zeolites with different Al contents in the framework to optimize zeolites’ thermodynamic adsorption properties for the CO2/CH4 separation and found that the selectivity strongly depended on the Al content.14 Pour et al. investigated the adsorption capacity and selectivity of 13X and clinoptilolite and claimed that 13X was a more promising adsorbent for CO2/CH4 separation, which was due to the larger surface area, larger pore volume, and lower Si/Al ratio.15 Among the zeolites, 13X with a faujasite-type framework, a low silicon-to-aluminum ratio (Si/Al = 1–1.7), large cavities (cage diameter: 11.6 Å), and windows (window diameter: 7.4 Å) has been considered the most promising adsorbent for CO2 separation and capture.13

The feed gas for the liquefied natural gas (LNG) is generally the pipeline natural gas, which is at high pressure with low CO2 concentration and must reduce the CO2 content from 3% to 50 ppm.16 Although the reports about the adsorption of gases above the critical temperature are abundant, the studies at high pressure are poorly reported,12 especially with low CO2 concentration. Moreover, in the comparison with low or medium pressure and high CO2 concentration, the adsorbents used in purification for LNG production must be more efficient with higher CO2 adsorption capacity and CO2/CH4 selectivity because of the high CH4 partial pressure in the feed.3 The improvements of the preparation and dehydration processes for the zeolites are convenient ways to enhance the separation performance. Campo et al. investigated the adsorption performance of an improved 13X zeolite and claimed that it was very appealing in the VSA process for methane upgrade.17 Finding a more efficient adsorbent and studying its CO2 separation at high pressure with low CO2 concentration are very important in the purification of LNG production.

This study is based on the previous dynamic experiments for adsorbent screening seen in Figure S1 and Table S1(Supporting Information), indicating that JLOX-500 among 6 X zeolites performed best in purification for LNG production. The main objectives of this work are to examine the relationship between the physiochemical properties and the adsorption and separation performance of X zeolites by systematically evaluating the CO2 separation performance of 13X, the benchmark X zeolite, and JLOX-500. First, the crystalline phase, chemical composition, and microstructure of the experimental samples were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD), energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis. Second, the adsorption isotherms of the pure gas at different temperatures were measured and fitted by the Langmuir, Freundlich, Sips, and Toth models. The adsorption capacity and selectivity were analyzed. Finally, the breakthrough curves were measured, and the adsorption capacity and separation factor were analyzed.

2. Experiment and Methods

2.1. Materials

13X and JLOX-500 particles were provided by Luoyang Jalon Micro-Nano New Materials Co. Ltd. (China). Table 1 lists their properties, and especially JLOX-500 was an improved X zeolite using fewer binders and an Al-richer X powder than 13X, which had the required mechanical strength.17 The information of the gases used in this study is shown in Table 2. Prior to the experiment, the samples were activated in a vacuum tube furnace for 2 h at 530 °C with a heat rate of 10 °C/min to remove the impurities and cooled down to ambient temperature in the vacuum environment.

Table 1. Properties of 13X and JLOX-500.

| zeolites | CAS reg. no. | pellet size (mm) | packing density (g/mL) | Si/Al ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13X | 1318-02-1 | 1.6–2.5 | ≥0.64 | 1–1.5 |

| JLOX-500 | 1318-02-1 | 1.6–2.5 | 0.62–0.66 | 1–1.5 |

Table 2. CAS Number, Purity, and Supplier of Gases.

| gases | CAS Reg. No. | supplier | mass fraction purity | molecular weight (g/mol) | analysis method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 124-38-9 | Qingdao Xinkeyuan Technology Co., LTD. | 99.999% | 44.01 | none |

| CH4 | 74-82-8 | Qingdao Xinkeyuan Technology Co., LTD. | 99.999% | 16.04 | none |

| N2 | 7727-37-9 | Qingdao Xinkeyuan Technology Co., LTD. | 99.999% | 28.01 | none |

| He | 7440-59-7 | Qingdao Xinkeyuan Technology Co., LTD. | 99.999% | 2.00 | none |

| 3%CO2 and 97%CH4 | Qingdao Xinkeyuan Technology Co., LTD. | 16.88 | CO2 concentration measuring device |

The texture properties of the experimental samples were analyzed using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 detector. The equilibrium adsorption isotherms of N2 on the zeolites were measured at −196 °C. The XRD patterns of samples were obtained at room temperature on Bruker D2-Phaser equipment using Cu-kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), 0.02° step width, and 4°/min scan speed.

2.2. Experimental Setup

The equilibrium and dynamic adsorption were constructed on the experimental setup at 30, 50, and 70 °C, shown in Figure 1. The empty column (EC), equilibrium adsorption column (EAC), and dynamic adsorption column (DAC) were made of a titanium alloy and could bear a maximum pressure of 6 MPa. The former two columns (EC and EAC) had the same dimension, length of 200 mm, and internal diameter of 25 mm, and the last one (DAC) had a length of 200 mm, an internal diameter of 12 mm, and a height to diameter ratio of 16.7 (>10).18

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for gas adsorption: 1,14-CO2, CH4, He, or gas mixture; 2,15-Pressure reducing valve; 3,16-Pressure gauge; 4,7,9,18,20-Needle valve; 5-Empty column (EC); 6-Venting; 8-Equilibrium adsorption column (EAC); 10-Vacuum pump; 11-Pressure transmitter; 12-Temprature sensor; 13-PC; 17-Mass flow controller; 19-Dynamic adsorption column (DAC); 21-Back-pressure valve; 22-CO2 concentration measuring device.

The measurement of the equilibrium adsorption isotherms was based on the volumetric method, and the adsorption capacity of the pure gas was calculated by the pressure difference before and after the equilibrium.19−22 The volumes of the column with connecting stainless tubes were 109 and 102 cm3 for EC and EAC measured with He, respectively. EC and EAC with activated samples were immersed in a water bath tank to keep the temperature constant measured by the temperature sensor. A certain amount of pure gas first entered EC. When the pressure measured by the pressure sensor was invariable for at least 30 min, opening the ball valve introduced the gas into EAC. When the pressure was balanced for at least 30 min, the equilibrium was regarded to be finished. With a certain pressure step, the procedure was repeated until the final pressure was reached.

The DAC with activated samples was equipped in the electric heating jacket to maintain the temperature constant. The pressure was regulated by the back-pressure valve. The flow rate was controlled by the mass flow controller. The CO2 concentration of the gas mixture at the outlet was in real-time measured by the CO2 concentration measuring device with a range of 0–5%VOL and a resolution of 0.01%VOL. When the CO2 concentration reached 3% in at least 10 min, the dynamic adsorption was regarded completed.

2.3. Theories and Methods

2.3.1. Isotherm Model

There were four adsorption isotherms commonly used to fit the adsorption data on zeolites: Langmuir, Freundlich, Sips, and Toth models. The Langmuir isotherm model was one of the most common adsorption isotherm models, which had been used to describe the monolayer adsorption behavior on the ideal surface given by eq 1.23 The Freundlich model was a semiempirical model and had been used to describe the adsorption behavior in a certain pressure region given by eq 2.24 The Sips isotherm model, a combination of Langmuir and Freundlich models, had been used to describe the heterogeneous systems, where each adsorbate molecule occupied more than one adsorption site given by eq 3.25 Another three-parameter isotherm model was the Toth model, which had good fitness to the experimental data in both low and high-pressure regions and had a wider application than the Sips model given by eq 4.24

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

where q is the equilibrium adsorption capacity (mmol/g), qm is the monolayer saturated adsorption capacity (mmol/g), and k is the affinity constant (kPa–1).

The parameter k was the constant of the adsorbent–adsorbate system at a specific temperature, which indicated how strong the interaction between the adsorbent and adsorbate was. The parameter n in the Freundlich model was usually more than unity, which was related to the nonlinear degree of the adsorption isotherm. When the parameter n was equal to unity, the Sips and Toth models were reduced to the Langmuir model of the ideal surface, so the parameter n in Sips and Toth could be used to represent the heterogeneity of the system.10

2.3.2. Henry’s Constant and Selectivity

Henry’s law constant was an affinity constant for the adsorbate molecules toward the adsorbent and correlated with their interaction between each other, the accurate calculation of which was critical to the design of the PSA, TSA, and column.15,26 When the pressure was sufficiently low (i.e., in Henry’s law region), the Langmuir equation usually used to obtain Henry’s constant was reduced to the linear Henry’s law equation given by eq 5.15,27

| 5 |

The Van’t Hoff equation showed the relationship between temperature and Henry’s constant given by eq 6.19

| 6 |

where KH is the Henry’s law constant (mmolg–1 kPa–1), KH0 is the constant of the Van’t Hoff equation (mmolg–1 kPa–1), ΔH is the adsorption heat (kJ/mol), R is gas constant, and T is temperature (K).

The equilibrium selectivity was the ratio of the Henry’s Law constant of adsorbate i to that of the adsorbate j at a certain temperature, which was an important parameter to evaluate the separation potential of an adsorbent for the different species of adsorbates.28

| 7 |

Ideal selectivity was the ratio of the equilibrium adsorption capacity of adsorbate i to that of the adsorbate j at the same pressure and temperature.29,30

| 8 |

2.3.3. Breakthrough Curve

The CO2 breakthrough curve represented the CO2 concentration of the gas mixture at the outlet of DAC with respect to time.15 The CO2 adsorption capacity on zeolites in dynamic adsorption could be calculated by the integration of CO2 breakthrough curves given by eq 9.31−34 With the difference in zeolite mass before and after the saturation, the CH4 adsorption capacity could be obtained given by eq 10.

| 9 |

| 10 |

where q1 and q2 are the adsorption capacity of CO2 and CH4, respectively (mmol/g); f is the flow rate of the feed gas at inlet (L/min); C0 and C are the CO2 concentration of the gas mixture at inlet and outlet, respectively (mmol/L); m is the mass of the adsorbent; tf is the breakthrough time (min); and Δm is the mass change of the zeolite (g). When the CO2 concentration at the outlet is 50 ppm, the tf is called the breakthrough time at beginning, and q1 is called CO2 adsorption capacity at beginning (CO2@50 ppm); when the CO2 concentration at the outlet is 3%, the tf is called the breakthrough time at saturation, and q1 is called CO2 adsorption capacity at saturation (CO2@3%).

The separation factor represented the ability to remove CO2 from the gas mixture.29

| 11 |

where Si,j is the separation factor of the adsorbate i over the adsorbate j; qi and qj are the adsorption capacity of the adsorbates i and j (mmol/g) in the dynamic adsorption; yi and yj are the concentration of the components i and j in the gas mixture.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterization

3.1.1. Chemical Composition

The chemical composition of the samples was determined by EDS given in Table 3. Both 13X and JLOX-500 consisted of the same species of elements, and O, Na, Al, and Si were the main elements found in experimental samples. Moreover, the percentage of each element in 13X and JLOX-500 differed from each other, and the Si/Al ratio was 1.34 and 1.44 for JLOX-500 and 13X, respectively.

Table 3. Chemical Composition of 13X and JLOX-500 Obtained by EDS.

| atom percentage/% |

Si/Al | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zeolites | O | Na | Mg | Al | Si | K | Ca | Fe | |

| 13X | 64.93 | 8.86 | 0.78 | 9.98 | 14.38 | 0.19 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 1.44 |

| JLOX-500 | 64.59 | 9.87 | 0.85 | 10.29 | 13.99 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 1.34 |

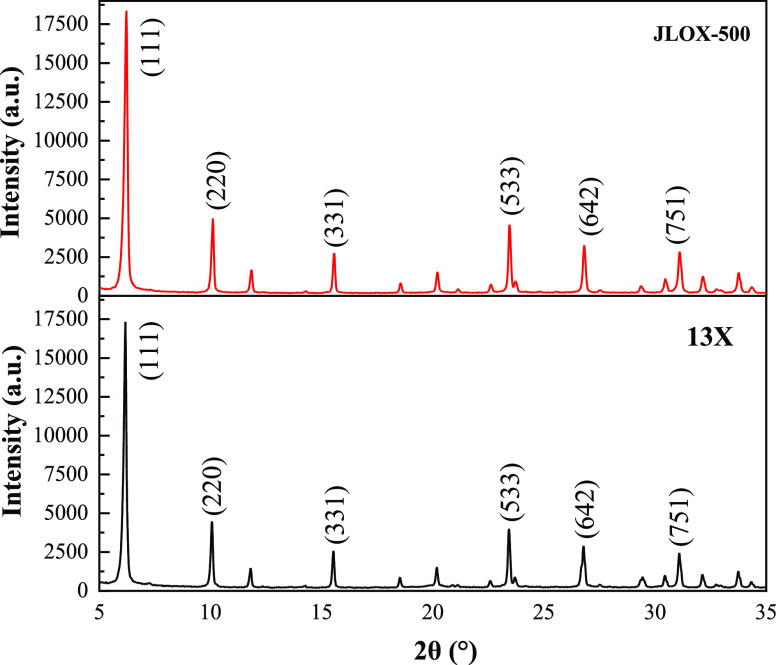

3.1.2. XRD Analysis

The XRD patterns of 13X and JLOX-500 are shown in Figure 2. The diffraction angles and intensities of the characteristic peak for the main crystallographic planes of both X zeolites are listed in Table 4. The crystalline phase was identified by the comparison with standard reference patterns,2 indicating that they both exhibited characteristic peaks of X zeolites without other impurity phases. The intensities of the characteristic peak for JLOX-500 were larger than those of 13X because the local electrostatic field changed by the different amounts of Na+. The fact that the improvement of the adsorption performance could be enhanced by the increase of intensity was concluded by some authors.33

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of 13X and JLOX-500.

Table 4. Diffraction Angles and Intensities of the Characteristic Peak for the Main Crystallographic Planes of Both X Zeolites.

| 13X |

JLOX-500 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| crystallographic plane index | 2θ (°) | intensity (a.u.) | 2θ (°) | intensity (a.u.) |

| (1, 1, 1) | 6.17 | 17,317 | 6.22 | 18,376 |

| (2, 2, 0) | 10.06 | 4469 | 10.10 | 4985 |

| (3, 3, 1) | 15.52 | 2554 | 15.56 | 2755 |

| (5, 3, 3) | 23.43 | 3992 | 23.45 | 4587 |

| (6, 4, 2) | 26.79 | 2891 | 26.81 | 3262 |

| (7, 5, 1) | 31.10 | 2445 | 31.10 | 2846 |

The diffraction angles of the characteristic peak for JLOX-500 were slightly larger than those of 13X. The calculated crystallite sizes of 13X and JLOX-500 were 91.6 and 78.7 nm by the Scherrer equation, respectively.2 JLOX-500 contained more Na+ in the unit cell than 13X, which could generate larger tensile force of the four-membered ring,33 making the framework of JLOX-500 more compact and the unit cell smaller than 13X.

3.1.3. SEM Analysis

The surface microstructures of 13X and JLOX-500 at different amplification factors were probed by SEM shown in Figure 3, respectively. This suggested that the particles of 13X and JLOX-500 contained the typical crystalline state of X zeolite, with a similar octahedral structure and nearly orbicular appearance.2 However, it could be seen from Figure 3a,c that the particle of JLOX-500 was more uniform with more dispersion, and had larger gaps between each other than 13X, because of the more compact structure resulting from more Al content consistent with XRD analysis. There were more microchannels and fewer binders on the surface of JLOX-500 than 13X because of the less amount of binders used in the granule process, which benefited the transportation and adsorption of adsorbates on JLOX-500.22,35

Figure 3.

SEM images of zeolites: (a), 13X at 15,000×; (b), 13X at 40,000×; (c), JLOX-500 at 15,000×; (d), JLOX-500 at 40,000×.

3.1.4. Pore Structure

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of 13X and JLOX-500 are shown in Figure 4. The adsorption isotherms were the combination of type IV and type I from the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) classification, and a type H4 hysteresis loop for p/p0 values of 0.4–1.0 was observed, which represented a complex pore structure consisting of micropores and mesopores.35 N2 adsorption on JLOX-500 was always larger than 13X at the same p/p0, and the area of the hysteresis loop for 13X was obviously larger than that of JLOX-500, which indicated that the ratio of mesopores to the micro-mesopores was larger. The pore size distributions (PSDs) of 13X and JLOX-500 are shown in Figure 5. The pore size interval of the peak for JLOX-500 was 0.84–0.98 nm and the peak appeared at 0.92 nm. These values for 13X were 0.88–1.02 and 0.95 nm. This fact would be due to the larger amount of Na+ in the framework of JLOX-500, which made the unit cell more compact and the blockage of the pore more obvious.33

Figure 4.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of zeolites at −196 °C: red, JLOX-500; blue, 13X; solid, adsorption; circle, desorption.

Figure 5.

PSDs of zeolites: (a) 13X; (b) JLOX-500.

The specific surface areas, pore volumes, and average pore sizes of 13X and JLOX-500 are shown in Table 5, which showed that the BET-specific surface area and total- and micropore volume of JLOX-500 were larger than those of 13X and that the average pore size of JLOX-500 was smaller than that of 13X, which was consistent with the PSDs. The ratio of the micropore volume to the total pore volume for JLOX-500 and 13X was 75.7 and 72.7%, respectively. Although the increase in Na+ and Al content would make the powder JLOX-500 more heavier than that of 13X,14 the decrease in the amount of the binder could benefit the particle JLOX-500 in the specific surface and pore volume.

Table 5. Specific Surface Areas, Pore Volumes, and Pore Diameters of X Zeolites.

| specific surface area (m2/g) | pore volume (m3/g) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| zeolites | BET | total | micropores | average pore diameter (nm) |

| 13X | 585 | 0.2908 | 0.2115 | 1.9902 |

| JLOX-500 | 626 | 0.3047 | 0.2306 | 1.9465 |

3.2. Equilibrium Adsorption

The adsorption isotherms of pure CO2 and CH4 on 13X and JLOX-500 were measured at 30, 50, and 70 °C at pressure up to 1000 kPa for CO2, and up to 4000 kPa for CH4. The CO2 adsorption capacities on 13X in this study at 50 and 70 °C at 100 kPa were 3.08 and 2.56 mmol/g, respectively. These values were respectively equal to those reported by Cavenati et al. (50 °C)36 and Mulgundmath et al. (70 °C),37 and the more information of comparison of adsorption capacity with other reported data is listed in Table S2. The trend of adsorption data was the same with other literature studies.15 The adsorption isotherms of CO2 and CH4 on 13X and JLOX-500 and their fitness to isotherm models are illustrated in Figure 6. According to IUPAC classification, the adsorption isotherms of CO2 and CH4 were classified as type I.22 The adsorption capacity of CO2 and CH4 on 13X was 4.96 and 2.07 mmol/g at 30 °C at 1000 kPa, respectively, whereas these values on JLOX-500 were 6.30 and 2.58 mmol/g under the same conditions.

Figure 6.

CO2 and CH4 adsorption isotherms on zeolites: (a) CO2 on 13X; (b) CO2 on JLOX-500; (c) CH4 on 13X; (d) CH4 on JLOX-500; square, 30 °C; circle, 50 °C; triangle, 70 °C; line, Toth with the best fitness.

The CO2 adsorption capacity was significantly higher than that of CH4 under the same conditions, which indicated the preferential adsorption of CO2 by X zeolites,38 because the quadrupole moment in CO2 molecules interacted with the surface of adsorbents more strongly than CH4, which did not have the quadrupole moment.36 The adsorbed amount of gas adsorbates would be reduced as the pressure decreased and temperature increased, owing to the faster desorption of gas molecules from the surface of zeolites at high temperature and low pressure.10 The adsorption capacities of CO2 and CH4 on JLOX-500 were both higher than those of 13X due to the larger space and more sites to accommodate more gas molecules in JLOX-500, which could be attributed to the larger specific surface area, larger pore volume, and lower Si/Al ratio.13,39

The isotherm model parameters for 13X and JLOX-500 are listed in Table S3. The order of the correlation coefficient value (R2) decreased as Toth > Sips > Langmuir > Freundlich. The Toth model had the best fitting behavior to the adsorption experiment data in both low- and high-pressure regions.24 The fitting behavior of the Sips model was not as good as that of the Toth model because Sips had no proper Henry’s law limits.10

The qm and k of CO2 were both larger than those of CH4 at the same temperature, owing to the stronger electrostatic interaction of CO2 with X zeolite as stated earlier. The qm values of CO2 and CH4 on JLOX-500 were larger than those of 13X, which could be attributed to the larger space and more sites of the JLOX-500 to accommodate more gas adsorbates.39 The k values of CO2 and CH4 on JLOX-500 were larger than those of 13X because more cations in the JLOX-500 created stronger electrostatic field in the framework, resulting in a stronger interaction of the adsorbates with JLOX-500.15,38 The qm and k decreased as temperature increased, showing that high temperature was harmful to gas adsorption and helpful to gas desorption, owing to the fact that the physical adsorption was an exothermic reaction.40

The positive value of the n parameter in the Freundlich model suggested that the adsorption on zeolites was physical adsorption.24 Parameter n decreased as temperature increased, indicating that high temperature reduced the nonlinear degree of the adsorption isotherm.10 The n parameter of CO2 on 13X in the Sips model was mostly equal to JLOX-500, and the same results were observed in the Toth model. However, Pour et al. found that in the Sips model, the heterogeneity of the system comprising CO2 and 13X was obviously higher than the system of clinoptilolite and CO2, owing to the lower Si/Al ratio for 13X.15 The different result could be attributed to the fact that 13X and JLOX-500 both belonged to the same species, X zeolite, and the difference in the Si/Al ratio between them was not as obvious as that between 13X and clinoptilolite.15 With the increase in temperature, n of the Sips model decreased and the n of the Toth model increased, which indicated that the heterogeneity of the system reduced at high temperature, which was the same as that in the study by Pour et al.15

3.3. Henry’s Constant and Selectivity

The Henry’s law constant for CO2 and CH4 on 13X and JLOX-500 was calculated from the Langmuir equation with the low-pressure adsorption data,15,27 and then equilibrium selectivity of CO2/CH4 was obtained. Like the k parameter in the adsorption isotherm models, Henry’s law constant, KH, also represented the affinity between the adsorbate and adsorbent. The large value of Henry’s constant represented that their interaction was strong.28 Henry’s law constant and equilibrium selectivity are listed in Table 6. KH for CO2 was larger than that of CH4 because of the quadrupole moment of CO2 as stated above. KH for CO2 and CH4 on JLOX-500 was larger than that for 13X, owing to the stronger electric field resulting from the lower Si/Al ratio and larger content of cations. With the increase in temperature, Henry’s law constant decreased because the physical adsorption was an exothermic reaction.40

Table 6. Henry’s Law Constant and Equilibrium Selectivity for CO2 and CH4.

|

KH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| zeolites | T(°C) | CO2 | CH4 | KH (CO2)/KH(CH4) |

| 13X | 30 | 0.3626 | 0.0044 | 82 |

| 50 | 0.1756 | 0.0030 | 58 | |

| 70 | 0.0857 | 0.0019 | 46 | |

| JLOX-500 | 30 | 0.8121 | 0.0062 | 131 |

| 50 | 0.3153 | 0.0040 | 79 | |

| 70 | 0.1245 | 0.0026 | 48 | |

The equilibrium selectivity represented the difference in affinity of different species of adsorbates concentrated on the adsorbent, which was an important parameter to evaluate the potential of an adsorbent in the separation and purification.41 The equilibrium selectivity of CO2/CH4 on JLOX-500 was larger than that of 13X at the same temperature, because of the lower Si/Al ratio in JLOX-500 generating stronger electric field, which interacted more strongly with the quadrupole moment of CO2 than 13X. The equilibrium selectivity decreased as the temperature increased because the adsorption heat of CO2 was larger than that of CH4.10,15

The adsorption heats for CO2 and CH4 on 13X and JLOX-500 were obtained by the Van’t Hoff equation.15,36 Ln(KH) with respect to the reciprocal of temperature (1/T) is plotted in Figure S2. The adsorption heats were 31.49 and 18.50 kJ/mol for CO2 and CH4 on 13X, respectively. These values were 40.50 and 18.77 kJ/mol on JLOX-500. The adsorption heat of CO2 was significantly higher than that of CH4, which was also due to the stronger electrostatic interaction. The CO2 adsorption heat on JLOX-500 was obviously higher than 13X owing to the lower Si/Al ratio, suggesting that the adsorption heat of CO2 increased as the Si/Al ratio decreased in X zeolites.14,15 However, the CH4 adsorption heat was mostly the same because there was no quadrupole moment in CH4 interacting with the electrostatic field, suggesting that the effect of the Si/Al ratio was little on CH4 adsorption heat on X zeolites.14 Palomino et al. obtained the same results for CO2 and CH4 adsorption heats on LTA zeolites.14

The ideal selectivity of CO2/CH4 for 13X and JLOX-500 at 30 °C was obtained and is shown in Figure 7. The highest ideal selectivity was achieved on JLOX-500, 9.03, at ambient pressure. This value for 13X was 8.58 and was similar to the value (8.47) obtained from the study by Pour et al..15 The more information of comparison of ideal seletivity with other reported data is listed in Table S2, indicating that JLOX-500 was a more efficient adsorbent than 13X. With the increase in pressure, ideal selectivity decreased and reached a constant value finally. This could be attributed to the fact that CO2 was more easily attracted to the surface of adsorbents in the low-pressure region than CH4, and then the finite adsorption sites reached the saturation as the pressure increased.15,20,42

Figure 7.

Ideal selectivity of CO2/CH4 on zeolites at 30 °C: orange, 13X; green, JLOX-500.

3.4. Dynamic Adsorption

The dynamic adsorption experiments were performed in DAC at 30, 50, and 70 °C at 4000 kPa with a flow rate of 1000 mL/min of the binary gas (3% CO2 and 97% CH4) as feed gas. The breakthrough curves of CO2 and CH4 on 13X and JLOX-500 are plotted in Figure 8. The breakthrough time, dynamic adsorption capacity of CO2 and CH4, and separation factors are listed in Table 7. When the feed gas entered DAC, the concentration of CO2 dropped to zero immediately, while CH4 increased to 100% until the column was breakthrough. Moreover, the adsorption capacity of CO2 was larger than that of CH4 except the case of the adsorption on 13X at 70 °C, even though the partial pressure of CO2 in the gas mixture was significantly less than CH4. Both of them indicated that these two zeolites, 13X and JLOX-500, had excellent separation of CO2 from the gas mixture in purification for LNG production at high pressure with low CO2 concentration.15,38 The CO2 adsorption capacity and separation factor on JLOX-500 were higher than those of 13X, which indicated that it was a better adsorbent to remove CO2 from the gas mixture than 13X in purification for LNG production. This could be attributed to the larger specific surface area, larger pore volume, and a lower Si/Al ratio.

Figure 8.

Breakthrough curves of CO2 and CH4 on zeolites: (a) 13X; (b) JLOX-500; square, 30 °C; circle, 50 °C; triangle, 70 °C. Experimental conditions: initial column condition = vacuumed for 30 min; feed composition = 3%CO2, 97%CH4; amounts of adsorbent = 11.507 g for 13X and 12.531 g for JLOX-500; feed flow rate = 1000 mL/min; the radius of particles = 1.6–2.5 mm; column dimensions = length of 200 mm and internal diameter of 12 mm.

Table 7. Adsorption Capacity of CO2 and CH4 and Separation Factor in the Dynamic Adsorption on 13X and JLOX-500.

| time (min) |

adsorption capacity (mmol/g) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zeolites | T/°C | beginning | saturation | CO2@50 ppm | CO2@3% | CH4 | separation factor |

| 13X | 30 | 14 | 44 | 1.64 | 3.02 | 2.34 | 42 |

| 50 | 11 | 37 | 1.28 | 2.60 | 2.36 | 37 | |

| 70 | 8 | 33 | 0.93 | 2.20 | 2.30 | 31 | |

| JLOX-500 | 30 | 32 | 45 | 3.46 | 4.01 | 2.12 | 62 |

| 50 | 25 | 40 | 2.70 | 3.55 | 2.20 | 52 | |

| 70 | 23 | 35 | 2.45 | 3.07 | 2.20 | 45 | |

The gas partial pressure was 120 kPa for CO2 in the gas mixture. The CO2 adsorption capacities in equilibrium adsorption on 13X were 3.71, 3.25, and 2.73 mmol/g at 120 kPa at 30, 50, and 70 °C, respectively. These values for JLOX-500 were 4.90, 4.10, and 3.39 mmol/g. It was clear that the CO2 adsorption capacity in a pure gas experiment was higher than CO2@3% (Table 7) in the gas mixture experiment at the same pressure, suggesting the existence of the competitive adsorption between CO2 and CH4, which was attributed to the fact that CH4 molecules at higher partial pressure accommodated more adsorption sites that would be accommodated by CO2 in pure gas adsorption. The CO2 adsorption capacity (CO2@3% and CO2@50 ppm) increased as the temperature decreased as the same as the separation factor of CO2/CH4, which indicated that the utility of the low-temperature environment in LNG plants could improve the adsorption process performance.3

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the combination of X powder with a lower Si/Al ratio and the less amount of binders is significantly effective in improving the adsorption and separation properties of X zeolites in purification for LNG production with low CO2 concentration in the feed gas and at high pressure. The improved changes in material characteristics were observed on JLOX-500 zeolite, such as higher intensities of a characteristic peak and smaller crystallite size in XRD, more microchannels on surface particles with a more uniform and higher dispersion degree in SEM, narrower pore size interval of the peak in PSDs, and larger surface area and pore volume in BET. The adsorption performance of X zeolites mainly depended on the specific surface area and pore volume especially at high pressure, while the CO2/CH4 separation performance was more closely related to the difference in affinity between CO2 and adsorbents because of the low Si/Al ratio affecting little to the interaction between CH4 and adsorbents. JLOX-500 was a better adsorbent in purification for LNG production in terms of higher adsorption capacity of CO2 and CH4, higher equilibrium and ideal selectivity, and higher separation facor in the lab experiment. A further investigation to identify the efficiency of JLOX-500 in the pilot experiment is underway.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support received from CNOOC Gas & Power Group Research & Development Center of China.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c01211.

Preliminary screening results of the commercial X zeolites, figures of the adsorption heat, literature review about the adsorption capacity of CO2 and CH4, and the isotherm model parameters (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhang X.; Myhrvold N. P.; Hausfather Z.; Caldeira K. Climate Benefits of Natural Gas as a Bridge Fuel and Potential Delay of Near-Zero Energy Systems. Appl. Energy 2016, 167, 317–322. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. J.; Fu Y.; Huang Y. X.; Tao Z. C.; Zhu M. Experimental Investigation of CO2 Separation by Adsorption Methods in Natural Gas Purification. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 329–337. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.06.146. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rufford T. E.; Smart S.; Watson G. C. Y.; Graham B. F.; Boxall J.; Diniz da Costa J. C.; May E. F. The Removal of CO2 and N2 from Natural Gas: A Review of Conventional and Emerging Process Technologies. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 94–95, 123–154. 10.1016/j.petrol.2012.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su F.; Lu C.; Chung A. J.; Liao C. H. CO2 Capture with Amine-Loaded Carbon Nanotubes via a Dual-Column Temperature/Vacuum Swing Adsorption. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 706–712. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2013.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J.; Nam Y. S.; Kang Y. T. Study on a Numerical Model and PSA (Pressure Swing Adsorption) Process Experiment for CH4/CO2 Separation from Biogas. Energy 2015, 91, 732–741. 10.1016/j.energy.2015.08.086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavenati S.; Grande C. A.; Rodrigues A. E. Removal of Carbon Dioxide from Natural Gas by Vacuum Pressure Swing Adsorption. Energy Fuels 2006, 20, 2648–2659. 10.1021/ef060119e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira M. A.; Ribeiro A. M.; Ferreira A. F. P.; Rodrigues A. E. Cryogenic Pressure Temperature Swing Adsorption Process for Natural Gas Upgrade. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 173, 339–356. 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.09.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Zhang J.; Wang L.; Cui X.; Liu X.; Wong S. S.; An H.; Yan N.; Xie J.; Yu C.; Zhang P.; Du Y.; Xi S.; Zheng L.; Cao X.; Wu Y.; Wang Y.; Wang C.; Wen H.; Chen L.; Xing H.; Wang J. Self-Assembled Iron-Containing Mordenite Monolith for Carbon Dioxide Sieving. Science 2021, 373, 315–320. 10.1126/science.aax5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackley M. W.; Rege S. U.; Saxena H. Application of Natural Zeolites in the Purification and Separation of Gases. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 61, 25–42. 10.1016/S1387-1811(03)00353-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Do D. D.Adsorption Analysis: Equilibria and Kinetics; Imperial College Press, 1998; vol. 2, pp. 11–69. [Google Scholar]

- Walton K. S.; Abney M. B.; LeVan M. D. CO2 Adsorption in Y and X Zeolites Modified by Alkali Metal Cation Exchange. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 91, 78–84. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2005.11.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talu O.; Zhang S. Y.; Hayhurst D. T. Effect of Cations on Methane Adsorption by NaY, MgY, CaY, SrY, and BaY Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. 1993, 97, 12894–12898. 10.1021/j100151a043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remy T.; Peter S. A.; van Tendeloo L.; van der Perre S.; Lorgouilloux Y.; Kirschhock C. E. A.; Martens J. A.; Xiong Y.; Baron G. V.; Denayer J. F. Adsorption and Separation of CO2 on KFI Zeolites: Effect of Cation Type and Si/Al Ratio on Equilibrium and Kinetic Properties. Langmuir 2013, 29, 4998–5012. 10.1021/la400352r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomino M.; Corma A.; Rey F.; Valencia S. New Insights on CO2-Methane Separation Using LTA Zeolites with Different Si/Al Ratios and a First Comparison with MOFs. Langmuir 2010, 26, 1910–1917. 10.1021/la9026656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pour A. A.; Sharifnia S.; NeishaboriSalehi R.; Ghodrati M. Performance Evaluation of Clinoptilolite and 13X Zeolites in CO2 Separation from CO2/CH4 Mixture. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 26, 1246–1253. 10.1016/j.jngse.2015.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sage V.; Hazewinkel P.; Khamphasith M.; Young B.; Burke N.; May E. F. High-Pressure Cryogenic Distillation Data for Improved LNG Production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 229, 115804 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.115804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campo M. C.; Ribeiro A. M.; Ferreira A. F. P.; Santos J. C.; Lutz C.; Loureiro J. M.; Rodrigues A. E. Carbon Dioxide Removal for Methane Upgrade by a VSA Process Using an Improved 13X Zeolite. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 143, 185–194. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2015.11.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malek A.; Farooq S. Determination of Equilibrium Isotherms Using Dynamic Column Breakthrough and Constant Flow Equilibrium Desorption. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1996, 41, 25–32. 10.1021/je950178e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pakseresht S.; Kazemeini M.; Akbarnejad M. M. Equilibrium Isotherms for CO, CO2, CH4 and C2H4 on the 5A Molecular Sieve by a Simple Volumetric Apparatus. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2002, 28, 53–60. 10.1016/S1383-5866(02)00012-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rad M. D.; Fatemi S.; Mirfendereski S. M. Development of T Type Zeolite for Separation of CO2 from CH4 in Adsorption Processes. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2012, 90, 1687–1695. 10.1016/j.cherd.2012.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.; Ju Y.; Park D.; Lee C. H. Adsorption Equilibria and Kinetics of Six Pure Gases on Pelletized Zeolite 13X up to 1.0 MPa: CO2, CO, N2, CH4, Ar and H2. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 292, 348–365. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.02.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golipour H.; Mokhtarani B.; Mafi M.; Khadivi M.; Godini H. R. Systematic Measurements of CH4 and CO2 Adsorption Isotherms on Cation-Exchanged Zeolites 13X. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2019, 64, 4412–4423. 10.1021/acs.jced.9b00473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Irving L. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica and Platium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. 10.1021/ja02242a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kareem F. A. A.; Shariff A. M.; Ullah S.; Dreisbach F.; Keong L. K.; Mellon N.; Garg S. Experimental Measurements and Modeling of Supercritical CO2 Adsorption on 13X and 5A Zeolites. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 50, 115–127. 10.1016/j.jngse.2017.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sips R. On the Structure of a Catalyst Surface. II. J. Chem. Phys. 1950, 18, 1024–1026. 10.1063/1.1747848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loughlin K. F.; Abouelnasr D. Critical Evaluation of Henry’s Law Constants for Nitrogen on the NaX (13X) Zeolite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 12970–12983. 10.1021/acs.iecr.1c01466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha D.; Bao Z.; Jia F.; Deng S. Adsorption of CO2, CH4, N2O, and N2 on MOF-5, MOF-177, and Zeolite 5A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1820–1826. 10.1021/es9032309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H.; Yi H.; Tang X.; Yu Q.; Ning P.; Yang L. Adsorption Equilibrium for Sulfur Dioxide, Nitric Oxide, Carbon Dioxide, Nitrogen on 13X and 5A Zeolites. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 188, 77–85. 10.1016/j.cej.2012.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D. A.; Mujčin M.; Trudeau E.; Tezel F. H. Pure and Binary Adsorption Equilibria of Methane and Nitrogen on Activated Carbons, Desiccants, and Zeolites at Different Pressures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2016, 61, 3163–3176. 10.1021/acs.jced.6b00245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy D. A.; Mujčin M.; Abou-Zeid C.; Tezel F. H. Cation Exchange Modification of Clinoptilolite −Thermodynamic Effects on Adsorption Separations of Carbon Dioxide, Methane, and Nitrogen. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 274, 327–341. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.08.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Vicario A.; Ochoa-Gómez J. R.; Gil-Río S.; Gómez-Jiménez-Aberasturi O.; Ramírez-López C. A.; Torrecilla-Soria J.; Domínguez A. Purification and Upgrading of Biogas by Pressure Swing Adsorption on Synthetic and Natural Zeolites. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2010, 134, 100–107. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2010.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. M.; Lim Y. H.; Jo Y. M. Evaluation of Moisture Effect on Low-Level CO2 Adsorption by Ion-Exchanged Zeolite. Environ. Technol. 2012, 33, 77–84. 10.1080/09593330.2011.551837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. J.; Zhu M.; Fu Y.; Huang Y. X.; Tao Z. C.; Li W. L. Using 13X, LiX, and LiPdAgX Zeolites for CO2 Capture from Post-Combustion Flue Gas. Appl. Energy 2017, 191, 87–98. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.01.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia L. G. T.; Agustini C. B.; Perez-Lopez O. W.; Gutterres M. CO2 Adsorption Using Solids with Different Surface and Acid-Base Properties. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103823 10.1016/j.jece.2020.103823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. J.; Tao Z. C.; Fu Y.; Zhu M.; Li W. L.; Li X. D. CO2 Separation from Offshore Natural Gas in Quiescent and Flowing States Using 13X Zeolite. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 1435–1446. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.09.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavenati S.; Grande C. A.; Rodrigues A. E. Adsorption Equilibrium of Carbon Dioxide on Zeolite 13X at High Pressures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2004, 49, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgundmath V. P.; Jones R. A.; Tezel F. H.; Thibault J. Fixed Bed Adsorption for the Removal of Carbon Dioxide from Nitrogen: Breakthrough Behaviour and Modelling for Heat and Mass Transfer. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 85, 17–27. 10.1016/j.seppur.2011.07.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardane R. V.; Shen M. S.; Fisher E. P.; Poston J. A. Adsorption of CO2 on Molecular Sieves and Activated Carbon. Energy Fuels 2001, 15, 279–284. 10.1021/ef000241s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Zhang W.; Chen X.; Xia Q.; Li Z. Adsorption of CO2 on Zeolite 13X and Activated Carbon with Higher Surface Area. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 710–719. 10.1080/01496390903571192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; Tezel F. H. Adsorption Separation of N2, O2, CO2 and CH4 Gases by β-Zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2007, 98, 94–101. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2006.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue M.; Farrusseng D.; Valencia S.; Aguado S.; Ravon U.; Rizzo C.; Corma A.; Mirodatos C. Natural Gas Treating by Selective Adsorption: Material Science and Chemical Engineering Interplay. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 155, 553–566. 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herm Z. R.; Krishna R.; Long J. R. Reprint of: CO2/CH4, CH4/H2 and CO2/CH4/H2 Separations at High Pressures Using Mg2(Dobdc). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 157, 94–100. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.