For its 125th anniversary issue, the editors of Science highlighted 125 big questions that continue to perplex humankind. The question at the heart of neuroscience and the core of anesthesiology about the biological basis of consciousness is listed just after “What is the Universe Made of.” Anesthetics annually ablate consciousness in just under 4% of humanity. As if that estimate were not astounding enough, time and again, the human brain journeys back from the abyss of general anesthesia with a renewed ability to sense the world. Henry Beecher’s challenge, issued 75 years ago,1 was to utilize anesthesia’s second power to probe the neural substrates enabling mental processes and to explore the variety of ways in which distinct general anesthetics transiently alter or ultimately extinguish perception. Placed into a more modern context, general anesthetics have the power to disconnect the salience of incoming sensory stimuli. Even under deep anesthesia, primary sensory cortex remains appropriately responsive; nevertheless, anesthetics fracture higher order perceptual representations consistent with cognitive unbinding.2 Remarkably, upon discontinuing anesthetic drug exposure, the brain spontaneously hops among meta-stable intermediate states as emergence proceeds.3 Neurophysiologic and behavioral functions recover,4 coherent experiences re-bind, and consciousness itself rebounds. The magic afforded by anesthesia’s second power thus continues to captivate philosophers and physicians, neuroscientists and naturalists.

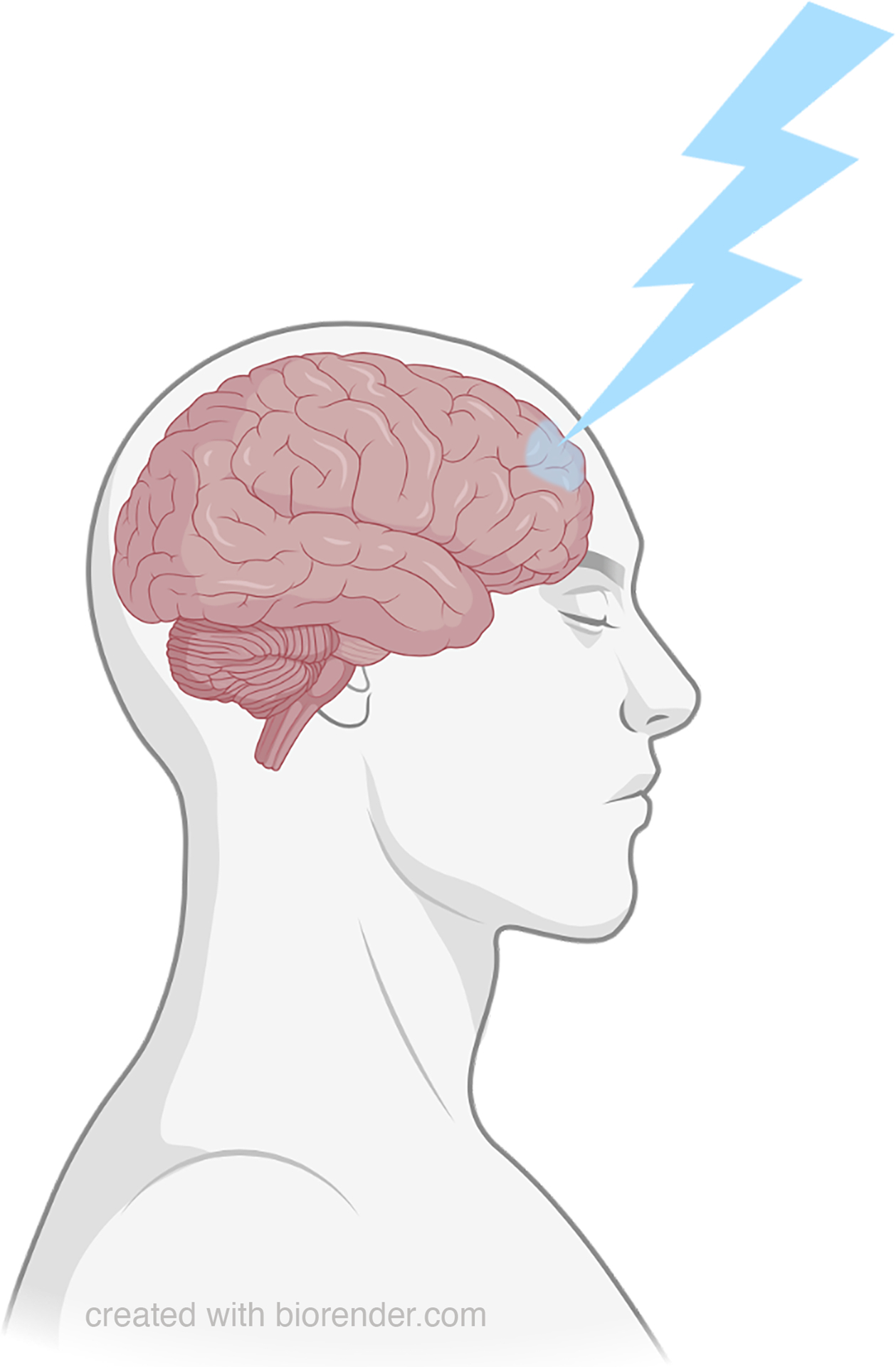

In this centennial year issue of Anesthesia & Analgesia, readers are treated to submissions that address anesthetic drug modulation of the content and/or level of consciousness.5–7 In an updated roadmap for the specialty, Dr. George Mashour, who founded the University of Michigan Center for Consciousness Science, issues an impassioned call for anesthesiology to provide fundamental neuroscientific insights,5 echoing and updating Beecher’s challenge. Mashour highlights leading, and at times competing, theoretical frameworks explaining consciousness, and focuses on the prefrontal cortex as a crucial node (figure 1).

Figure 1:

Schematic Reactivation of the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex encompasses a broad array of anatomically-heterogeneous subregions. Each has its own widespread, yet distinct pattern of cortical and subcortical connectivity. The prefrontal cortex sends reciprocal projections to arousal-promoting targets in the brain stem and diencephalon, supporting the notion that it can modulate the level of consciousness. Moreover, at least one prefrontal subregion is a requisite member in all of the six large-scale brain networks: the default-mode, dorsal attention, ventral attention, frontoparietal, cingulo-opercular and salience networks.8 From rodents up through humans, multiple lines of evidence identify a central role of the prefrontal cortex in supporting cognition. In humans, prefrontal circuits enable complex executive functions such as problem solving or decision-making that require planning of goal-directed behaviors, creative thinking, mind wandering, and even ruminating.9 Hence, it is not surprising that general anesthetic-induced modulation of prefrontal function has been hypothesized as an essential mechanism by which sedative hypnotics erode the content of consciousness. However, it is important to point out that since each distinct prefrontal cortical node is reciprocally connected to a corresponding node in the parietal cortex, some question the primary importance of prefrontal, as opposed to posterior parietal, hot spots supporting cognition. See for example the work of Ihalainen et al.10

By considering mechanistic overlap among physiologic, pharmacologic, and pathologic states in which consciousness is compromised, Mashour emphasizes the immense opportunity anesthesiology affords. Leveraging the ability of chemically and mechanistically distinct general anesthetics to reversibly perturb, indefinitely impair, and yet, remarkably permit cognitive reassembly, investigators have an incredible set of tools to objectively interrogate the circuit activity patterns that permit or prohibit perception. Study of the forward state transition into, and the reverse state transition out of anesthetic-induced unresponsiveness, along with the careful inclusion of sub-hypnotic dosing schemes offer added rigor in the quest to identify critical neural correlates of consciousness. The capacity to study recovery of consciousness during emergence differentiates anesthetic states from comatose ones in which recovery proceeds unpredictably, incompletely, or not at all. Nevertheless, despite this distinction, metabolic markers, neurophysiological imaging, and electrophysiological complexity of cortical activity all suggest that common correlates can distinguish states of (un)consciousness arising from neurologic disorders of consciousness, natural nightly “disorders” of consciousness found during sleep, and pharmacologic states of altered consciousness.11–15 Translational opportunities abound to mechanistically test these and other neural correlates with the full suite of modern neuroscientific tools in animal models.

Work in rodents by Pal, Mashour, and colleagues uses the righting reflex as a gold standard behavioral surrogate for the return of consciousness, along with spectral analysis of the electroencephalogram (EEG) to determine cortical activation. They previously demonstrated that cholinergic stimulation of prefrontal cortex rouses rats stably anesthetized and continuing to inhale 1.9%−2.4% sevoflurane.16 Such impressive antagonism of the anesthetized state can occur with successful targeting of prelimbic and infralimbic regions of the prefrontal cortex, but not with cholinergic stimulation of the medial or posterior parietal cortex and not with noradrenergic stimulation. Moreover, in an attempt to address the necessity of activation of the prefrontal cortex on anesthetic state transitions, Huels and colleagues targeted injections of the sodium channel blocker, tetrodotoxin, into prelimbic cortex, barrel cortex, or parietal association cortices.17 While putative dysregulation of action potential signaling in all cortical areas facilitated induction of sevoflurane anesthesia, only inactivation of the prefrontal cortex impaired emergence from sevoflurane,17 supporting a role for the prefrontal cortex in modulating the level of consciousness.18

As the major source of cholinergic innervation of the prefrontal cortex originates in the basal forebrain, one might rightly wonder whether enhancing cholinergic input to prefrontal cortex is similarly sufficient to alter arousal and restore wakefulness from states of natural sleep. Indeed, blue light driven optogenetic stimulation of cholinergic basal forebrain neurons induces rapid transitions from non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep to waking or rapid eye movement (REM) sleep states with enhanced cortical activity, in which vivid dreams may occur.19 Using chemogenetic activation or electrical stimulation of the basal forebrain, Dean and colleagues further demonstrate that they can elevate prefrontal acetylcholine levels, elicit EEG activation and behavioral arousal, with concomitant increases in heart and respiratory rates.6 While seemingly less efficacious than reverse dialysis delivery of carbachol into the prefrontal cortex itself,16 the ability of bilateral electrical stimulation of the basal forebrain to destabilize and/or outright antagonize states of sevoflurane anesthesia is partially dependent upon the prefrontal cortex. Local administration of tetrodotoxin into the prefrontal cortex markedly attenuated the efficacy of basal forebrain stimulation to precipitate arousal during ongoing sevoflurane anesthesia.6 Hence, work in the rodent model supports the conclusion that prefrontal cortical modulation does indeed alter the level of consciousness.

In their ground-breaking publication on consciousness and neuroscience, Crick and Koch suggested that science first focus on the neural correlates of consciousness as a proxy for the content of consciousness itself.20 Their underlying logic was that the content of specific experience must ultimately be encoded by the summated electrical activity of higher order networks. Since this proposition, a variety of neural correlates of consciousness have been postulated in both humans and animals. In the third submission in this 100th anniversary year issue of Anesthesia & Analgesia, Brito and colleagues utilize two well studied neural correlates of consciousness, Lempel-Ziv complexity and normalized symbolic transfer entropy.7 Such measures have previously been shown to track states of consciousness.21,22 When applied to the spontaneous EEG, Lempel-Ziv complexity distinguishes non-responsive wakefulness patients who fail to display any overt signs of awareness, from minimally conscious patients who exhibit intermittent evidence of awareness. Further, as recently reviewed,23 Lempel-Ziv complexity decreases during states of NREM sleep and as individuals enter GABAergic states of anesthetic induced unconsciousness. Symbolic transfer entropy has provided landmark evidence in humans that hypnotic doses of mechanistically distinct general anesthetics—propofol, sevoflurane, and ketamine—produce a common disruption of frontal to parietal feedback connectivity, while leaving feedforward parietal to frontal connectivity intact.24

Returning to the central question of prefrontal acetylcholine levels and neural correlates of consciousness, Brito and colleagues sought to strengthen correlative associations. Using a high density intracranial EEG in rats exposed to sub-hypnotic doses of ketamine or nitrous oxide, they demonstrate increases in prefrontal and parietal acetylcholine levels with increased Lempel-Ziv complexity.7 The profile of acetylcholine release differed markedly between ketamine and nitrous oxide. Ketamine consistently elevated levels, while nitrous oxide only transiently increased acetylcholine during induction, followed by a consistent decrease during maintenance. Despite these agent-specific differences, the roughly linear correlation with complexity remained as extracellular acetylcholine levels varied more than four-fold. The authors’ single chosen sub-hypnotic dose of ketamine or nitrous oxide may leave some readers wanting a fuller characterization of additional doses of these psychedelic anesthetics. Inclusion of hypnotic doses, more easily achieved with ketamine, might best cross-validate the human directional connectivity correlates24 in animal models with simultaneous invasive neurophysiologic sampling.

As we embark upon this 2nd century of research in anesthesiology and consciousness sciences, it will be imperative not only to identify reliable neural correlates of consciousness, but to ultimately uncover the molecular, neuronal, and circuit causes enabling consciousness itself. In heeding Mashour’s charge to the specialty,5 the field could finally realize anesthesia’s second power and ultimately see beyond the pioneering vision of Crick and Koch.

Financial Disclosures:

Supported by R01 GM088156 and by R01 GM144377

Glossary

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- NREM

non-rapid eye movement

- REM

rapid eye movement

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: nothing to declare

References

- 1.Beecher HK. Anesthesia’s Second Power: Probing the Mind. Science 1947;105:164–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mashour GA. Consciousness unbound: toward a paradigm of general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2004;100:428–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hudson AE, Calderon DP, Pfaff DW, Proekt A. Recovery of consciousness is mediated by a network of discrete metastable activity states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:9283–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mashour GA, Palanca BJ, Basner M, Li D, Wang W, Blain-Moraes S, Lin N, Maier K, Muench M, Tarnal V, Vanini G, Ochroch EA, Hogg R, Schwartz M, Maybrier H, Hardie R, Janke E, Golmirzaie G, Picton P, McKinstry-Wu AR, Avidan MS, Kelz MB. Recovery of consciousness and cognition after general anesthesia in humans. Elife 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mashour GA. Consciousness. Anesth Analg 2022;this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean JG, Fields CW, Brito MA, Silverstein BH, Rybicki-Kler C, Fryzel AM, Groenhout T, Liu T, Mashour GA, Pal D. Inactivation of Prefrontal Cortex Attenuates Behavioral Arousal Induced by Stimulation of Basal Forebrain During Sevoflurane Anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2022;this issue? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brito MA, Li D, Fields CW, Rybicki-Kler C, Dean JG, Liu T, Mashour GA, Pal D. Cortical Acetylcholine Levels Correlate with Neurophysiologic Complexity during Subanesthetic Ketamine and Nitrous Oxide Exposure in Rats. Anesth Analg 2022;this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon V, D’Esposito M. The role of PFC networks in cognitive control and executive function. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022;47:90–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zamani A, Carhart-Harris R, Christoff K. Prefrontal contributions to the stability and variability of thought and conscious experience. Neuropsychopharmacology 2022;47:329–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ihalainen R, Gosseries O, de Steen FV, Raimondo F, Panda R, Bonhomme V, Marinazzo D, Bowman H, Laureys S, Chennu S. How hot is the hot zone? Computational modelling clarifies the role of parietal and frontoparietal connectivity during anaesthetic-induced loss of consciousness. Neuroimage 2021;231:117841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodart O, Gosseries O, Wannez S, Thibaut A, Annen J, Boly M, Rosanova M, Casali AG, Casarotto S, Tononi G, Massimini M, Laureys S. Measures of metabolism and complexity in the brain of patients with disorders of consciousness. Neuroimage Clin 2017;14:354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarasso S, Boly M, Napolitani M, Gosseries O, Charland-Verville V, Casarotto S, Rosanova M, Casali AG, Brichant JF, Boveroux P, Rex S, Tononi G, Laureys S, Massimini M. Consciousness and Complexity during Unresponsiveness Induced by Propofol, Xenon, and Ketamine. Curr Biol 2015;25:3099–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frohlich J, Toker D, Monti MM. Consciousness among delta waves: a paradox? Brain 2021;144:2257–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee M, Sanz LRD, Barra A, Wolff A, Nieminen JO, Boly M, Rosanova M, Casarotto S, Bodart O, Annen J, Thibaut A, Panda R, Bonhomme V, Massimini M, Tononi G, Laureys S, Gosseries O, Lee SW. Quantifying arousal and awareness in altered states of consciousness using interpretable deep learning. Nat Commun 2022;13:1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darracq M, Funk CM, Polyakov D, Riedner B, Gosseries O, Nieminen JO, Bonhomme V, Brichant JF, Boly M, Laureys S, Tononi G, Sanders RD. Evoked Alpha Power is Reduced in Disconnected Consciousness During Sleep and Anesthesia. Scientific reports 2018;8:16664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pal D, Dean JG, Liu T, Li D, Watson CJ, Hudetz AG, Mashour GA. Differential Role of Prefrontal and Parietal Cortices in Controlling Level of Consciousness. Curr Biol 2018;28:2145–52 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huels ER, Groenhout T, Fields CW, Liu T, Mashour GA, Pal D. Inactivation of Prefrontal Cortex Delays Emergence From Sevoflurane Anesthesia. Front Syst Neurosci 2021;15:690717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung LS, Luo T. Cholinergic Modulation of General Anesthesia. Curr Neuropharmacol 2021;19:1925–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han Y, Shi YF, Xi W, Zhou R, Tan ZB, Wang H, Li XM, Chen Z, Feng G, Luo M, Huang ZL, Duan S, Yu YQ. Selective activation of cholinergic basal forebrain neurons induces immediate sleep-wake transitions. Curr Biol 2014;24:693–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crick F, Koch C. Consciousness and neuroscience. Cereb Cortex 1998;8:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee U, Blain-Moraes S, Mashour GA. Assessing levels of consciousness with symbolic analysis. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 2015;373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mateos DM, Guevara Erra R, Wennberg R, Perez Velazquez JL. Measures of entropy and complexity in altered states of consciousness. Cogn Neurodyn 2018;12:73–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott G, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics as a treatment for disorders of consciousness. Neuroscience of Consciousness 2019;2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee U, Ku S, Noh G, Baek S, Choi B, Mashour GA. Disruption of frontal-parietal communication by ketamine, propofol, and sevoflurane. Anesthesiology 2013;118:1264–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]