Abstract

Objectives

Good social connection is associated with better health and wellbeing. However, social connection has distinct considerations for people living in long-term care (LTC) homes. The objective of this scoping review was to summarize research literature linking social connection to mental health outcomes, specifically among LTC residents, as well as research to identify strategies to help build and maintain social connection in this population during COVID-19.

Design

Scoping review.

Settings and Participants

Residents of LTC homes, care homes, and nursing homes.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE(R) ALL (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (Ovid), Scopus, Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Embase and Embase Classic (Ovid), Emcare Nursing (Ovid), and AgeLine (EBSCO) for research that quantified an aspect of social connection among LTC residents; we limited searches to English-language articles published from database inception to search date (July 2019). For the current analysis, we included studies that reported (1) the association between social connection and a mental health outcome, (2) the association between a modifiable risk factor and social connection, or (3) intervention studies with social connection as an outcome. From studies in (2) and (3), we identified strategies that could be implemented and adapted by LTC residents, families and staff during COVID-19 and included the articles that informed these strategies.

Results

We included 133 studies in our review. We found 61 studies that tested the association between social connection and a mental health outcome. We highlighted 12 strategies, informed by 72 observational and intervention studies, that might help LTC residents, families, and staff build and maintain social connection for LTC residents.

Conclusions and Implications

Published research conducted among LTC residents has linked good social connection to better mental health outcomes. Observational and intervention studies provide some evidence on approaches to address social connection in this population. Although further research is needed, it does not obviate the need to act given the sudden and severe impact of COVID-19 on social connection in LTC residents.

Keywords: Social integration, social networks, social engagement, social support, social isolation, social capital, loneliness, nursing homes, long-term care

Coronavirus (COVID-19) has taken a disproportionate toll on people living in long-term care (LTC) homes. To protect LTC residents from COVID-19 infection, infection control measures have included prohibiting visitors and restricting activities and interactions with other residents and staff in the home. Although these measures may have reduced risk of infection, they have also presented their own health risks through the devastating impact on resident's social connection.1 , 2

Social connection is good for health and well-being3, 4, 5 and important to quality of life in LTC homes.6, 7, 8 Social connection also has distinct considerations for those living in LTC homes. Most LTC residents are older adults, and many have complex health needs, including sensory, cognitive,9 or mobility impairment that can impact social connection.10, 11, 12 For many residents, families play an integral role, including participating in care, representing the resident's perspective and history, and maintaining family connections.13 , 14 Within LTC homes, residents share space, have daily interactions with staff and take part in congregate activities. Communities surrounding LTC homes, including volunteers and care professionals, also participate in the lives of many LTC home residents. Taken together, LTC residents are a population with unique needs and opportunities for building and maintaining social connection.

The current scoping review was undertaken to provide LTC residents, families, and staff with (1) a summary of research evidence linking social connection to mental health outcomes for LTC residents; and (2) strategies they may implement quickly, during COVID-19, to address social connection in this population. These objectives align with the needs of stakeholders representing or supporting LTC as well as COVID-19 research priorities identified internationally.15 , 16

Methods

This is a substudy of a larger scoping review,17 conducted to address a broad set of research questions, with a flexible and iterative approach.18 We followed the 6-stage approach19 , 20 and report our results in accordance with the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews.21

Step 1: Identifying the Research Questions

Our questions were developed to support a rapid knowledge synthesis and mobilization of current evidence on the needs of mental health services, delivery, and related guidelines in the COVID-19 context. Our questions were directed by stakeholders (see Step 6, below):

-

(1)

What mental health outcomes are associated with social connection for people living in LTC homes?

-

(2)

What interventions and strategies might support social connection for people living in LTC homes in the context of infectious disease outbreaks like COVID-19?

Step 2: Searching for Relevant Studies

We selected studies identified from the larger scoping review whereby published journal articles reporting results of observational and intervention studies were eligible if they reported a quantitative measure of social connection in a population of adult residents of LTC homes.

We included research on aspects of social integration that have been identified specifically for research in LTC homes,22 including social networks,23 social engagement23 , 24 and disengagement,25 social support,23 social isolation,26 and social capital.22 , 27 The subjective experience of social integration, including loneliness,28 perceived isolation29 and social connectedness,30 were also included. Given the diversity of terminology used in this area of research, our search strategy used a broad list of terms.17 In this article, we refer to all these above-listed concepts collectively as social connection.

We included studies reporting results specifically for residents of LTC homes, nursing homes or care homes (ie, adults living in residential facilities, whose staff provide help with most or all daily activities and 24-hour care and supervision). These terms reflect differences in terminology between countries, but were chosen for their overlap with the international consensus definition of nursing home.31 We hereafter refer to them collectively as LTC homes.

To identify studies, we developed a comprehensive search strategy17 with an experienced information specialist who first conducted the search in MEDLINE(R) ALL (in Ovid, including Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily) and then translated it into CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycINFO (Ovid), Scopus, Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), Embase and Embase Classic (Ovid), Emcare Nursing (Ovid), and AgeLine (EBSCO). All searches were conducted from the databases’ inception through to the date the search was executed (July 2019), limited to English language. Covidence (www.covidence.org) and Endnote were used to manage the review process, including the deduplication of database results.32

Step 3: Selecting Studies

As part of the larger review, in the first and second phase of study selection, 2 reviewers independently screened article titles and abstracts then full articles to identify potentially relevant studies (ie, studies that quantified social connection in an adult population living in LTC homes). In both selection steps, any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. For the current subanalysis, 2 reviewers independently analyzed the full-text articles to identify the subset that reported the:

-

(1)

association between any measure of social connection and a mental health outcome,

-

(2)

association between a modifiable risk factor(s) and any measure of social connection, or

-

(3)

results of intervention study (randomized and nonrandomized) whereby the outcome was any measure of social connection.

We also checked our list against 3 recent systematic reviews of interventions to address social connection in LTC homes.33, 34, 35 No formal quality assessment of the studies was undertaken. To be more inclusive of studies of residents with dementia, we included articles that reported social interaction as a measure of social connection, but we did not include measures of social response,36 social behavior,37 social interest,38 social communication (eg, eye contact, facial expressions, body language, etc)39 or engagement40 that was not explicitly characterized as social.

Step 4: Charting the Data

Two reviewers then independently extracted data from these studies.17 We summarized studies according to study characteristics and reported a narrative synthesis and mapping of the results.19 , 20 We reported the results in 2 parts, in alignment with the 2 questions guiding the review.

Step 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

We took an iterative approach to reporting our results. The first author reported consolidated results back to the study team who reviewed the results, suggested refinements, and provided insights on the findings. From the studies identified in criteria (2) and (3) (see Step 3, above), the study team identified strategies that were seen to be potentially quick and relatively low-cost to implement and adapt by LTC residents, families, and staff in the COVID-19 pandemic; the articles informing these strategies were included in our review.

Step 6: Consulting With Stakeholders

In our initial protocol,17 we had described opportunities to present to LTC residents, families, and staff in a LTC home. COVID-19 made these consultations impractical. However, community participation is critical in the COVID-19 context41; communities can help identify solutions and are well placed to devise collective responses.42 Thus, for this review, we worked with partners from organizations who represent these stakeholder groups: Behavioral Supports Ontario, Family Councils Ontario, and the Ontario Association of Residents’ Councils. These members of our study team were involved in priority-setting (defining the review questions), analyzing data, interpreting and contextualizing the results, and coauthoring the current review and related reports and presentations.

Results

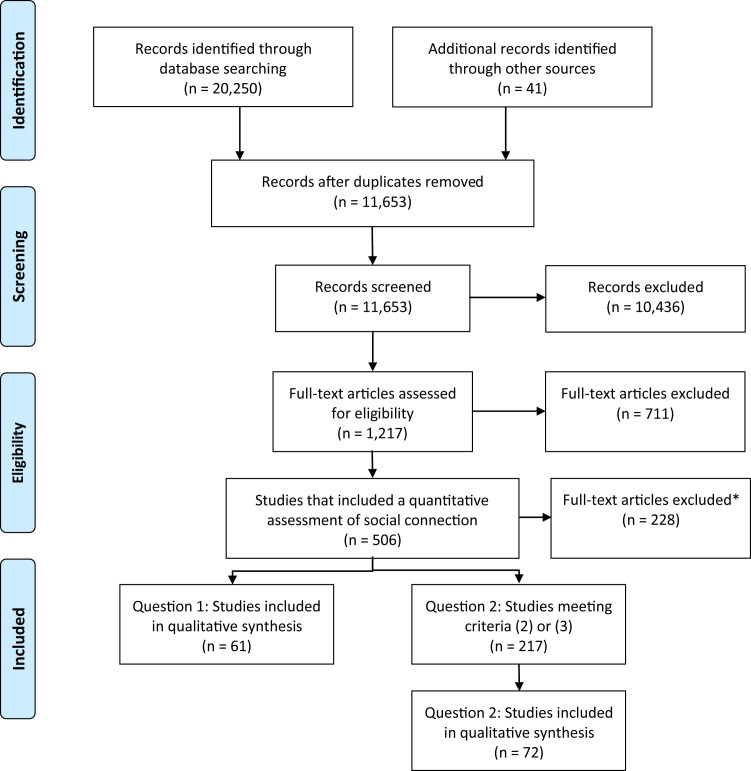

Our initial search yielded 20,291 titles, which reduced to 11,653 after deduplication. We distilled this list to 133 articles after full-text review (Figure 1 ). The characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1 . More than half (n=81; 61%) of the studies were published after 2010. The largest proportion of studies were from North America (n=52; 39%), mostly the United States (n=46). Overall, roughly one-third (n=49; 37%) of studies included fewer than 100 LTC residents in the sample; however, smaller studies made up a larger proportion of intervention studies (n=32; 65%) compared with observational studies in question 1 (n=13; 21%) and question 2 (n=4; 17%). The most commonly investigated aspects of social connection were social engagement (n=41; 31%), social support (n=34; 26%), and loneliness (n=32; 24%), and some studies investigated multiple measures.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram that describes the flow of information through the review's study search and selection. ∗ Exclusions: social connection assessed but descriptive or psychometric studies or studies with other outcomes (eg, physical health, quality of life, etc).

Table 1.

Description of Published Research Articles Included in Scoping Review

| Study Characteristics | Question 1 (N=61) |

Question 2 |

Total (N=133) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational (N=23) |

Intervention (N=49) |

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Year of publication | ||||||||

| Pre-1990 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 5 |

| 1990-1999 | 8 | 13 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 8 |

| 2000-2009 | 16 | 26 | 6 | 26 | 13 | 27 | 35 | 26 |

| 2010-2019 | 36 | 59 | 14 | 61 | 31 | 63 | 81 | 61 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Asia | 20 | 33 | 3 | 13 | 16 | 33 | 39 | 29 |

| Europe | 11 | 18 | 9 | 39 | 9 | 18 | 29 | 22 |

| North America | 24 | 39 | 10 | 43 | 18 | 37 | 52 | 39 |

| Other/multiple | 6 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 13 | 10 |

| Study design | ||||||||

| Cross-sectional | 47 | 77 | 20 | 87 | NA | NA | 67 | 50 |

| Cohort | 11 | 18 | 3 | 13 | NA | NA | 14 | 11 |

| Other/not stated | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Quasi-experimental | NA | NA | NA | NA | 29 | 59 | 29 | 22 |

| Randomized controlled trial | NA | NA | NA | NA | 17 | 35 | 17 | 13 |

| Sample size (LTC home residents) | ||||||||

| <100 | 13 | 21 | 4 | 17 | 32 | 65 | 49 | 37 |

| 100-249 | 26 | 43 | 5 | 22 | 11 | 22 | 42 | 32 |

| 250-499 | 10 | 16 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 6 | 17 | 13 |

| ≥500 | 12 | 20 | 10 | 43 | 2 | 4 | 24 | 18 |

| Not stated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Aspect(s) of social connection∗ | ||||||||

| Loneliness | 11 | 18 | 3 | 13 | 18 | 37 | 32 | 24 |

| Social capital | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Social engagement | 23 | 38 | 12 | 52 | 6 | 12 | 41 | 31 |

| Social interaction | 6 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 17 | 13 |

| Social isolation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| Social network | 10 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 14 | 11 |

| Social participation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| Social relations | 0 | 0 | 5 | 22 | 8 | 16 | 13 | 10 |

| Social support | 26 | 43 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 34 | 26 |

| Social withdrawal | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

NA, not applicable.

Column percentage adds to more than 100% because some studies investigated multiple aspects of social connection.

What Mental Health Outcomes Are Associated With Social Connection for People Living in LTC Homes?

We identified 61 studies that tested the association between social connection and mental health outcomes. The most commonly investigated aspects of social connection were social support (n=26; 43%), social engagement (n= 23; 38%), loneliness (n= 11; 18%), and social network (n=10; 16%). We categorized these studies according to the reported mental health outcomes: depression; responsive behaviors; mood, affect, and emotions; anxiety; medication use; cognitive decline; death anxiety; boredom; suicidal thoughts; psychiatric morbidity; and daily crying (see Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1)—although we acknowledge overlap between these categories.

Table 2.

Summary of Studies Included in Question 1, Total Number of Studies Included and Number of Studies With Statistical Evidence of Positive Impact of 1 (or More) Measures of Social Connection on the Mental Health Outcome

| Mental Health Outcome | Number of Studies Reporting |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mental Health Outcome | Positive Impact of Social Connection∗ | |

| Depression | 35 | 28 |

| Responsive behaviors | 9 | 7 |

| Mood, affect, and emotions | 8 | 7 |

| Anxiety | 3 | 2 |

| Medication use | 3 | 0 |

| Cognitive decline | 2 | 2 |

| Death anxiety | 2 | 2 |

| Boredom | 2 | 2 |

| Suicidal thoughts | 2 | 2 |

| Psychiatric morbidity | 1 | 1 |

| Daily crying | 1 | 1 |

Some studies included multiple outcomes; total does not reflect number of studies included in review.

Where studies report unadjusted and adjusted estimates, classified by adjusted estimates; where studies report cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses, classified by longitudinal analysis.

Depression

There were 35 studies that tested the association between social connection and depression. Most (n=28) of the studies were cross-sectional. Better social connection was associated with less depression in 28 studies.43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 One study showed a cross-sectional association at baseline but not in the longitudinal (1-month follow-up) analysis.71 Five studies did not find statistically significant associations,72, 73, 74, 75, 76 and 1 found social support was associated with increased depression among new nursing home residents.77

Responsive Behaviors

Nine studies tested the association between social connection and responsive behaviors, typically reporting physical and verbal expression outcomes. Six studies found that social connection was associated with a decrease in some responsive behaviors,50 , 78, 79, 80, 81, 82 but one study found number of family visits was not associated with agitation83 and another found high social interaction was associated with increased agitation.84 One study found that social engagement was associated with a decrease in responsive behavior only among residents without dementia.85

Mood, Affect, and Emotions

Eight studies tested the association between social connection and mood, affect, and emotion outcomes. All provide some evidence that social connection was associated with better mood, affect, and emotions45 , 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91 although one study showed cross-sectional associations at baseline did not extend to longitudinal analysis (with 1-month follow-up)71 and 2 studies reported that, among residents with dementia, social interaction was associated with both positive and negative affect88 and expressions (and the quality of interaction, positive, negative or neutral, may differentiate positive and negative expressions).89

Anxiety

Three cross-sectional studies tested the association between social connection and anxiety. Two studies reported that better social connection was associated with less anxiety,43 , 46 whereas 1 study of new residents found that higher informational social support was associated with more anxiety.77

Cognitive Decline

Two cohort studies, both using data from the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI), tested the association between social engagement and cognitive performance; both found that more social engagement was associated with less cognitive decline.92 , 93

Other Mental Health Outcomes

Three studies used RAI data to test the association between social engagement and (antipsychotic or hypnotic) medication use but produced mixed results.50 , 94 , 95 Two cross-sectional studies reported associations between social support and lower death anxiety.96 , 97 Two cross-sectional studies reported impacts of social support, loneliness, and social engagement in relation to suicidal ideation.98 , 99 Two cross-sectional studies reported that better social connection was associated with less boredom.100 , 101 Studies also linked social connection to daily crying102 and psychiatric morbidity.103

What Interventions/Strategies Support Social Connection for People Living in LTC Homes in the Context of Infectious Disease Outbreaks Like COVID-19?

After reviewing the studies that met criterion 2 or 3, our team identified 12 interventions and strategies as potentially quick and relatively low-cost to implement and adapt in the current COVID-19 pandemic. There were 23 observational studies and 49 intervention studies that reported social connection outcomes and were relevant to these 12 strategies (see Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). Among observational studies, the most commonly investigated aspect of social connection was social engagement (n=12; 52%), most often using health administrative data and the RAI index of social engagement. Among intervention studies, the most commonly investigated aspect of social connection was loneliness (n= 18; 37%), most often using the UCLA Loneliness Scale.

Table 3.

Summary of Studies Included in Question 2, Total Number of Studies Included and Number of Studies With Statistical Evidence of Positive Impact of Strategy on 1 (or More) Measures of Social Connection, by Study Type (Observational or Intervention)

| Question 2: Interventions or Strategies to Support Social Connection | Total (nstudies) | Number of Observational Studies Reporting |

Number of Intervention Studies Reporting |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Associated With Social Connection | Intervention | Positive Impact on Social Connection | ||

| Manage pain | 13 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Address vision and hearing loss | 9 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| Sleep at night, not during the day | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Find opportunities for creative expression | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Exercise | 8 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 3 |

| Maintain religious and cultural practices | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Garden, either indoors or outside | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 |

| Visit with pets | 14 | 1 | 1 | 13 | 10 |

| Use technology to communicate | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Laugh together | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Reminisce about events, people, and places | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Address communication impairments and communicate nonverbally | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

Some studies included multiple exposures/interventions; total does not reflect number of studies included in review.

Manage pain

Eight observational studies tested the association between pain and social relationships or loneliness.104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111 Two studies found that pain was associated with reduced social relationships scores106 and increased loneliness.109 Another study showed that, among residents with persistent pain, analgesic use was associated with improved social engagement.111 Five studies found no association between pain and social connection.104 , 105 , 107 , 108 , 110 However, 3 of these studies reported that the association between pain and social connection only disappeared after adjusting for other variables,104 , 105 , 107 including in a study that suggested influence of pain on social engagement may depend on the level of cognitive impairment.104 Of the 5 intervention studies addressing pain, 4 showed beneficial impact on social interaction and involvement,112 social relations,113 and loneliness114 , 115 whereas 1 showed no impact on loneliness.116

Address vision and hearing loss

Seven observational studies, all using RAI-MDS data, consistently showed an association between visual impairment and lower social engagement.117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123 For residents with cataracts, cataract surgery was associated with improvements in social interaction.124 One randomized controlled trial, assessing the effect of treating uncorrected refractive error (getting glasses), showed improved social interaction.125 Although fewer studies linked hearing impairment to social engagement,122 , 123 and some find no association,117 , 119 , 121 taken in context with the apparent influence of dual sensory loss,120 hearing loss should also be addressed.

Sleep at night, not during the day

One observational study found that sleep disturbances were associated with lower levels of social engagement126 whereas another found no association between sleep difficulties and social relationships.106 One intervention study tested the impact of a sleep intervention and reported increased participation in social activities.127

Find opportunities for creative expression

Five intervention studies tested the impact of creative expression programs, such as art, music, and storytelling, on social connection; 3 reported improvements in social engagement128 and social interaction,129 but there were mixed results for social relations and social isolation.130, 131, 132

Exercise

Two observational studies found the associations between physical activity or participation in physiotherapy and social connection were not statistically significant.133 , 134 Six intervention studies tested the impact of exercise programs. Of the 2 studies that tested the impact of tai chi, one reported improvement in social relationships135 and the other found no impact on social support.136 For other physical activity interventions, one study reported no change in social relations,137 another reported improvements in social participation,138 and the third, carried out among residents with chronic pain, found decreased loneliness.139 Another study that tested the combination of qigong and art suggested that only the art intervention affected social relationships.132

Maintain religious and cultural practices

Three observational studies tested associations between social connection and religious activities, spirituality, and faith. One reported that, for both African American and white nursing home residents, preference for religious activities and drawing strength from faith were associated with higher social engagement.119 Another showed that religious coping was positively associated with social support.140 The third study reported that the association between spirituality and social engagement was not statistically significant.118

Garden, either indoors or outside

Five studies tested the effect of horticulture and indoor gardening programs for LTC residents. Three studies that compared the program to usual care found that the gardening programs were associated with improvements in social relationship and loneliness outcomes.141, 142, 143 However, the 2 studies that compared the programs with other interventions found no effect.144 , 145

Visit with pets

Twelve studies assessed the impact of pet interactions and animal-assisted therapy on social connection, and 2 more studied robotic animals. Pet interaction and animal assisted therapy studies showed beneficial impacts on social connection (including reducing loneliness,146, 147, 148, 149 and social interaction)148 , 150, 151, 152, 153, 154 except in 2 studies.155 , 156 Another study suggested that any visits (ie, with or without pets) increased social interaction.157 Two studies assessing the impact of robotic animals reported beneficial impacts on loneliness158 , 159 and 1 found that the impact of a robotic dog was similar to that of a live dog.158

Use technology to communicate

Four studies assessed the impact of communication technology, but 2 were small-scale pilot studies.160 , 161 The 2 quasi-experimental studies that tested the effect of regular videoconferencing with family members showed beneficial effects for both social support and loneliness.162 , 163

Laugh together

Three intervention studies reported the impact of humor therapy; one study of laughter therapy (using laughter and yoga breathing techniques) reported decreased emotional and social loneliness,164 whereas the other 2 interventions were not found to reduce loneliness165 or social disengagement.166

Reminisce about events, people, and places

Seven interventions studies tested reminiscence therapy or programs. These studies showed increases in social participation,167 , 168 social engagement,169 , 170 social interaction,171 social network,170 and decreases in loneliness172 but not social relationships167 , 168 or social support.170 One study found no effect of the intervention on social engagement.173

Address Communication Impairments and Communicate Nonverbally

Five observational studies showed that impaired receptive (understanding others) and/or expressive (making oneself understood) communication was associated with reduced social connection. Three studies used RAI-MDS data to examine communication among LTC residents overall118 , 122 , 123 whereas 2 studies used assessments of expressive and receptive communication in individuals with dementia.174 , 175

Discussion

Our systematic search of published research on social connection in LTC residents identified 133 studies. We found 61 studies that assessed the association between social connection and mental health outcomes; overall, these studies suggest social connection is possibly associated with better mental health in LTC residents. We used 72 observational and intervention studies, combined with stakeholder experience and advice, to highlight 12 strategies that might be used and adapted by LTC residents, families, and staff to help build and maintain social connection in LTC residents.

Among the studies linking social connection to mental health outcomes, many had methodological limitations. In particular, some studies did not incorporate strategies to account for confounding and most were cross-sectional, making it impossible to establish temporal order. For example, with respect to the latter, studies included here considered social connection as a predictor of depression whereas others identified in our search considered it an outcome176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181—in reality, bidirectional relationships are likely.182 Further, studies that described and compared populations within LTC were infrequent; few studies reported stratified results (eg, by race or ethnicity,119 , 122 age,97 sex,94 or level of cognitive impairment)48 , 85 , 92 or restricted to certain populations (eg, new residents).77 , 95 Research assessing differences by resident-level demographic and clinical factors and other characteristics (eg, distinguishing new and established residents) would inform the development of interventions, as would incorporating measures of home-level characteristics.

We identified 12 strategies that may help build and maintain social connection in LTC residents during COVID-19. Our review builds on previous reviews of interventions to address social connection among LTC residents33, 34, 35 by also considering observational research and contextualizing findings through consultation with organizations representing LTC residents, families, and staff. However, similar to those reviews, we found limited research evidence and that most intervention studies were not randomized and often excluded residents with cognitive impairment. We also found no studies conducted in the context of infectious disease outbreaks. Although our stakeholders provided insights into the applicability of these strategies during COVID-19, given the frequency of disease outbreaks in LTC homes, more research is needed to address the specific challenges such scenarios present to LTC.

We also note 2 important caveats to the strategies we identified. First, some represent fundamental aspects of resident care whereas others will not be relevant to every LTC resident or home. In particular, pain is reported as a measure of nursing home quality,183 and the importance of addressing sleep,184 hearing,185 and vision186 have previously been highlighted for this population. For other strategies, each resident's needs, values, family situation and circumstances will be distinct just as every LTC home context will present unique challenges and opportunities for implementation; for example, some strategies rely partly or entirely on technology, which presents its own challenges to residents, families, and homes.1 Second, enacted in the catastrophically common scenario of infection control measures that exclude families and isolate residents from others in the home, all strategies rely on a healthy, sustained LTC workforce. Without these vital interactions with families and other residents, problems of deteriorating mental health among residents are compounded by already-strained LTC staff who are now further challenged to provide care, including social connection, to residents. LTC homes worldwide must be supported to address problems of chronic understaffing187 and a workforce crisis in LTC.188

Our scoping review used a comprehensive search strategy to identify published literature that quantified aspects of social connection in LTC residents. Still, we acknowledge certain limitations. First, we did not review intervention studies using social connection as a means of addressing some other outcome (eg, responsive behaviors).189, 190, 191, 192 Although we had intended to include such studies,17 in practice, categorizing interventions as targeting social connection was difficult to operationalize. We acknowledge that characterizing these studies would have been useful to delineate the associations between social connection and mental health. Second, we did not describe associations among the different social connection variables, that is, how concepts such as social networks, social support, social engagement, loneliness, and social capital relate to one another. Studies that clarify the conceptual underpinnings and relationships among these factors22 , 27 and the mechanisms by which interventions/strategies might impact social connection193 will advance knowledge in this area. Third, our definition of social connection excluded outcomes such as eye contact, facial expressions, and body language and this may have disproportionately excluded studies of persons with advanced dementia. New measures of social connection, developed specifically for persons with dementia (and at different dementia severities),194 , 195 will be helpful for future research in this area. Finally, we initiated this scoping review, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,17 to describe the literature but not to make recommendations for practice.196 As such, we did not include an assessment of the quality of the studies included in our review,19, 20, 21 and this may limit interpretation for policy and practice.

Conclusions and Implications

Our study underscores the importance of social connection for the mental health of residents of LTC homes and identifies strategies that may help build and maintain social connection in this population during COVID-19. Although these findings rely on incomplete evidence, this apparent limitation does not diminish the imperative to address social connection within LTC homes—both during COVID-19 and beyond. Still, further research is needed to explore the role of social connection over time and for different populations within LTC homes as well as in the context of infectious disease outbreaks.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to Ellen Snowball, Kaitlyn Lem, Omar Farhat, Jenny Jing, Souraiya Kassam, and David Jagroop for their assistance selecting the studies and charting the data. Ellen Snowball also created the infographic art summarizing results available at http://www.encoarteam.com/index.html.

Footnotes

This research was supported by a “Knowledge Synthesis: COVID-19 in Mental Health and Substance Use” operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). JB, AI, and KM are supported by the Walter & Maria Schroeder Institute for Brain Innovation and Recovery. They are also members of the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA). The study sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of the article.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Table 1.

Summary of Studies Used to Address Question 1, Presented According to Mental Health Outcome

| First Author, Year | Country | Population (N=) | Inclusion/Exclusion Related to Cognition | Study Design | Social Exposure | Mental Health Outcome | Study Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (n=35 studies) | |||||||

| Ahmed, 2014∗ | Egypt | Geriatric home residents (N=240) | Exclusion: cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 25) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using a 3-item loneliness scale | Depression, using the shorter version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) | Loneliness often (OR 5.02, 95% CI 1.96-12.90; P = .001) or sometimes (OR 3.79, 95% CI 1.35-10.66; P = .011) associated with depression |

| Chau, 2019 | Australia | Long-term care residents (N=81) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 18) | Cohort | Social support, using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Depression, using Geriatric Depression Scale short form (GDS-15) | Worse perceived social support was associated with increased depression over time (P < .001) |

| Cheng, 2010 | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=71) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 18) | Cross-sectional | Social network, using the network mapping procedure Social support (received and provided) Social engagement (visits), using contact frequency |

Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Number of contacts with and social support from staff and fellow residents and support provided to all network members were all inversely associated with depression (P < .05) |

| deGuzman, 2015 | The Philippines | Nursing home residents (N=151) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Social Support Scale and support from family and health care providers or from other personnel | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Social support, from either family or staff, was not associated with depression |

| Drageset, 2013∗ | Norway | Nursing home residents (N=227) | Inclusion: “cognitively intact” [0.5 or less on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR)] | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the revised Social Provision Scale (SPS): attachment, social integration, opportunity of nurturance, and reassurance of worth | Depression, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Social support subdimensions of social integration (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93-0.99; P = .02) and reassurance of worth (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.91-0.99; P = .006) were associated with less depression |

| Farber, 1991 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=70) | Exclusion: moderate-to-severe dementia | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Quality of Relationship Scale Social engagement (visits and phone calls), using family-reported information on frequency of visits and phone calls |

Depression, using Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale | Quality of relationships (P = .001) but not frequency of interaction (P = .23) were inversely associated with depression |

| Fessman, 2000 | United States | Nursing facility residents (N=170) | Inclusion: sufficient cognitive ability | Cross-sectional | Social network, using assessment of close friends Social engagement (visits), using who, and how often, outsiders visited them (number of visitors/month) Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale |

Depression, using the Zung depression scale | The number of visits per month from friends and relatives was unrelated to depression; however, the number of close friends was inversely associated with depression (P < .01). Loneliness was positively associated with depression, but statistically significant only for those with Alzheimer's disease. |

| Gan, 2015 | China | Nursing home residents (N=71) | None specified | Cohort | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale | Depression, using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale | Loneliness was associated with depression (P < .05); mediation analysis indicated that rumination did not mediate the relationship between loneliness and depression |

| Hjaltadóttir, 2012∗ | Iceland | Nursing home residents (N=3694) | None specified | Not stated | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Depression, using RAI Depression Rating Scale (DRS) | Compared to residents with higher social engagement, moderate (OR 5.14, 95% CI 4.26-6.19; P < .001) and low (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.80-2.67; P < .001) social engagement associated with depression symptoms |

| Hollinger-Smith, 2000 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=130) | None specified | Cohort | Social support, using the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) social resources indicators Social support (affective), using the Perception of Touch Scale |

Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Diagnosed depression, using clinical diagnosis on record |

Using GDS, social resources and affective social support were inversely associated with depression (P < .001) Using diagnosed depression, only affective social support was associated with depression (P < .001) |

| Hsu, 2014 | Taiwan | Long-term care (intermediate care facility and nursing home) residents (N=174) | Inclusion: cognitively intact as assessed by the Short Portable Mental Status. Exclusion: diagnosis of dementia |

Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using the Socially Supportive Activity Inventory (SSAI) evaluating 9 different types of social activities and frequency, meaningfulness, and enjoyment | Depression, using the Chinese Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) | In 8 of 9 social activities, the more meaningful and enjoyable the resident rated the activity, the more significant the correlation for fewer depressive symptoms (P < .05); of all the activities, only the “pleasure trips” showed no association with depressive symptoms |

| Jongenelis, 2004 | The Netherlands | Nursing home residents (N=350) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 15) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the de Jong Loneliness Scale Social support, using the shortened version of the Social Support List–Interaction (SSL12-I) scale |

Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Schedule of Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) | Loneliness was found to be associated with subclinical (OR 3.38, 95% CI: 1.72-6.63), minor depression (OR 4.52, 95% CI 2.06-9.90), and major depression (OR 22.32, 95% CI 2.55-195.66); lack of social support (OR 3.32, 95% CI 1.01-10.94) was associated with major depression |

| Keister, 2006∗ | United States | New nursing home residents (N=114) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Modified Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors assessing 4 dimensions of social support (informational, tangible, emotional, and integration support) | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | One dimension of social support was positively associated with depressive symptoms; as tangible support increased, depressive symptoms increased (P < .05) |

| Kim, 2009 | Korea and Japan | Nursing home residents (N=184) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Depression, using the shorter version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) | Loneliness was a significant predictor of depression for the Korean (P < .01) and Japanese residents (P < .01) |

| Kroemeke, 2016∗ | Poland | Nursing home residents (N=180) | Exclusion: diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairments | Cross-sectional (at baseline) and longitudinal (after 1 mo) | Social support (received and provided), using the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) | Depression, using Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale | In cross-sectional analysis, there was an inverse relationship between receiving support and depression; in longitudinal analysis, neither received support nor given support were associated with depressive symptoms |

| Krohn, 2000 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=29) | Inclusion: “cognitively intact" | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | There was a positive association between loneliness and depression (P = .020). |

| Kwok, 2011 | China | Nursing home residents (N=187) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 18) | Cross-sectional | Social support (perceived institutional peer support and perceived family support), using modified version of the Lubben Social Network Scale | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | No association between perceived family support and depressive symptoms; higher level of perceived institutional peer support was significantly correlated with a lower level of depressive symptoms (P < .001) |

| Leedahl, 2015 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=140) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MDS 3.0 Brief Interview for Mental Status < 13 or MDS 2.0 Cognitive Scale score > 2) | Cross-sectional | Social network, using the concentric circle (ie, egocentric network) approach Social capital, using the indicators norms of reciprocity and trust Social support, using a modified version of the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors Social engagement, using Likert scale questions about participation in various social activities within and outside the nursing home and a question about group/organization participation |

Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Social networks had a positive indirect relationship with mental health, primarily via social engagement; social capital had a positive direct relationship on mental health |

| Lin, 2007 | Taiwan | Nursing home residents (N=138) | Inclusion: “cognitively intact" Exclusion: score of 4 or less on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SMPSQ) |

Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Social Support Scale to measure perceived social support from nurses, nurse aides, family, and roommates | Depression, using Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale | Lack of social support from nurses (P = .034), family (P < .001), and roommates (P = .012) were correlated with depressive symptoms; in adjusted analysis, social support from family was inversely associated with depression (P < .001) |

| Lou, 2013 | Hong Kong | Long-term care residents (N=1184) | None specified | Cohort | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Depression, using the RAI Depression Rating Scale (DRS) | At baseline, social engagement was inversely associated with depressive symptoms; increases in social engagement had a significant inverse association with changes in depressive symptom scores over time |

| McCurren, 1999 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=85) | Exclusion: diagnosis and symptom progression consistent with advanced irreversible dementia | Cross-sectional | Social network, using the Salamon-Conte Life Satisfaction in the Elderly Scale (LSES) social contacts subscale | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Social contact was inversely correlated with depression (P = .001) |

| Nikmat, 2015 | Malaysia | Nursing home residents (N=149) | Inclusion: cognitive impairment (Short Mini Mental State Examination (SMMSE) < 11) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness/social isolation, using the Friendship Scale (FS) | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Loneliness/social isolation was associated with depression (P < .001) |

| Patra, 2017 | Greece | Nursing home residents (N=170) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) Social engagement (visits), using frequency of visits by relatives |

Depression, using the shorter version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) | Social support was inversely associated with depression (P < .001); fewer visits from relatives was associated with depression (P < .001) |

| Potter, 2018 | United Kingdom | Care home residents (N=510) | None specified | Cohort | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement | Depression, using the shorter version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) | Controlling for home-level covariates, social engagement was not associated with depression |

| Pramesona, 2018 | Indonesia | Nursing home residents (N=181) | Exclusion: diagnosed with severe cognitive impairment or dementia |

Cross-sectional | Social support, using a classification: from spouse, family, staff or others or no one; and type of support, using a classification: psychological or financial or no support | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | In univariate analysis, lack of social support was associated with depression (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.15-3.87; P = .15) but not in adjusted analysis (OR 2.11, 95% CI 0.48-9.32; P = .33); type of support was not associated with depression |

| Segal, 2005 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=50) | Exclusion: cognitive impairment | Cross-sectional | Social support, using Social Support List of Interactions (SSL12-I) | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Correlation between social support and depression was not statistically significant |

| Somporn, 2012 | Thailand | Nursing home residents (N=237) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale Social engagement, using scheduled social activities |

Depression, using the Thai Geriatric Depression Scale (TGDS-30) | Loneliness (P < .001), and lack of social activity (P < .001) were associated with depressive symptoms |

| Tank Buschmann, 1994 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=50) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support (affective), using the Perception of Touch Scale | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Affective social support was associated with reduced depression (P < .001) |

| Tiong, 2013 | Singapore | Nursing home residents (N=375) | Exclusion: uncommunicative or unable to respond meaningfully (eg, dementia) | Cross-sectional | Social engagement (visits), using questions about frequency of visitors | Depression, using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria | Lack of social contact was associated with depression (OR 2.33, 95% CI 1.25-4.33) |

| Tosangwarn, 2018 | Thailand | Care home residents (N=128) | Exclusion: severe cognitive impairment | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Thai Version of Multidimensional Scale of the Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Depression, using the Thai Geriatric Depression Scale (TGDS-30) | Perceived social support was inversely associated with depression (OR 0.969, 95% CI 0.939-0.999; P = .044). |

| Tsai, 2005 | Taiwan and Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=364) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 16 for participants with no formal education; MMSE score < 20 for primary school graduates or higher) | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Social Support Scale (including social support network, quantities of social support, and satisfaction with social support subscales) | Depression, using the Chinese Geriatric Depression Scale–Short Form | Satisfaction with social support and social support network were significantly and negatively related to depressive symptoms (P < .01) |

| Tu, 2012 | Taiwan | Long-term care residents (N=307) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Social Support Scale (assessing social companionship, emotional support, instrumental support, and informational support) | Depression, using Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale | Among social support subscales, only social companionship was inversely associated with depression in adjusted analysis (P < .05); all were associated with depression in unadjusted analysis |

| Vanbeek, 2011 | The Netherlands | Long-term care dementia unit (nursing and residential home) residents (N=502) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using the Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Depression, using the MDS Depression Rating Scale (DRS) | Association between social engagement and depression was not statistically significant |

| Yeung, 2011 | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=187) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using a questionnaire about family support; residential social support; and residential social participation | Depression, using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Only residential social support was associated with depression (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.24-0.53) |

| Zhao, 2018 | China | Nursing home residents (N=323) | Exclusion: severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 10) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using a Chinese version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale Social support, using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) |

Depression, using the Hospital Depression Scale (HDS) | The association between loneliness and depressive symptoms was partially mediated by resilience; the indirect effect of the mediation model was moderated by social support |

| Responsive behaviors (n=9 studies) | |||||||

| Chen, 2000 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=129) | Exclusion: no cognitive impairment (MMSE score > 24) | Cross-sectional | Social interaction, using the Social Interaction Scale (SIS) subscales: Institutional Interaction and Family/Community Interaction | Aggressive behavior, using the Ryden aggression scale 2 (RAS2) with 3 subscales: physically aggressive behavior); verbally aggressive behavior; sexually aggressive behavior | Social interaction was inversely associated with physical aggression (P < .05) but not verbal or sexual aggression |

| Choi, 2018 | Korea | Nursing home residents (N=1447) | None specified (but results stratified by dementia) | Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Aggressive behaviors, using RAI data on physical abuse, verbal abuse, socially inappropriate or destructive behaviors and/or resistance to care in the last 3 d | Social engagement was associated with less aggressive behavior among those without dementia (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.15-0.62; P < .001) but not among those with dementia (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.51-1.08) |

| Cohen-Mansfield, 1990 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=408) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social network (quality and size/density), using the Hebrew Home Social Network Rating Scale (HHSNRS) | Screaming, using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) | Poor quality of the social network was associated with screaming (P < .01) |

| Cohen-Mansfield, 1992 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=408) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social network, using a questionnaire developed by research team—frequency of contact with staff, visitors, and others; intimacy with staff and visitors; frequency of visitors | Agitation, using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI): aggressive behavior, physically nonaggressive behavior and verbally agitated behavior | Intimacy of social network inversely associated with total number of agitated behaviors (P < .01), aggressive behavior (P < .01), and verbally agitated behavior (P < .01); the size and density of the social network did not differentiate agitated individuals from other residents |

| Draper, 2000 | Australia | Nursing home residents (n=25 cases and n=25 controls) | None specified | Case-control | Social engagement, using the Social Activity Inventory (SAI) items on group activities, hobbies, independent ADL, physical activities, culture-specific programs, visitors, and the involvement of family and friends in the nursing home | Vocally disruptive behavior | Participation in group activities (P = .005), hobbies (P = .004), and culture-specific programs (P = .005) less common among cases |

| Hjaltadóttir, 2012∗ | Iceland | Nursing home residents (N=3694) | None specified | Not stated | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Behavioral symptoms, using RAI | Compared to residents with higher social engagement, moderate social engagement was associated with behavioral symptoms (OR 1.38, 95% CI 1.15-1.66; P < .001) but not those with lowest social engagement (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.73-1.09) |

| Kolanowski, 2006 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=30) | Inclusion: dementia diagnosis that met DSM-IV criteria, and MMSE score <24 | Cross-sectional | Social interaction, using the Passivity in Dementia Scale (PDS) Social withdrawal, using the withdrawal subscale of the Multidimensional Observation Scale for Elderly Subjects (MOSES) |

Agitation, using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) | Agitation was significantly greater under high social interaction as compared with low social interaction (P < .001) regardless of the extraversion score |

| Livingston, 2017 | England | Care home residents (N=1489) | Inclusion: diagnosis of dementia or screened positive for dementia | Cross-sectional | Social engagement (visits), using the number of family visits | Agitation, using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) Neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation), using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) |

Number of family visits was not associated with CMAI agitation caseness (OR 0.984, 95% CI 0.914-1.059) or NPI agitation caseness (OR 0.990, 95% CI 0.976-1.005) |

| Marx, 1990 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=408) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social network (quality and size/density), using the Hebrew Home Social Network rating Scale (HHSNRS) | Aggression (physical, verbal, sexual, and self-abuse), using the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) | Poor quality of social network associated with aggression, including physical, verbal, and self-abuse (P < .05) |

| Mood, affect, and emotion (n=8 studies) | |||||||

| Beerens, 2018 | The Netherlands | Long-term care residents with dementia (N=115) | Inclusion: a formal diagnosis of dementia | Cross-sectional | Social interaction, using the Maastricht Electronic Daily Life Observation-tool (MEDLO-tool) | Mood, using the Maastricht Electronic Daily Life Observation-tool (MEDLO-tool) | Social interaction was associated with higher (positive) mood (P < .001) |

| Cheng, 2010∗ | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=71) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 18) | Cross-sectional | Social network, using the network mapping procedure Social support (received and provided) Social engagement (visits), using contact frequency |

Positive affect, using the Chinese Affect Scale | Network size, contact with family, support from family, support from staff and fellow residents, and support provided to all network members were all associated with positive affect (P < .05) |

| Cohen-Mansfield, 1993 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=408) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social network, using the Hebrew Home Social Network Rating Scale | Depressed affect, using the Depression Rating Scale. | Poor quality of social networks associated with depressed affect |

| Gilbart, 2000 | Canada | Continuing care and long-term care residents (N=385) | None specified | Not stated | Social support, using questions about type and level of support provided by a number of possible significant others Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) |

Affect, using the Short Happiness and Affect Research Protocol (SHARP) Positive and negative affectivity, using the Measure of the Intensity and Duration of Affective States (MIDAS) Mood state, using RAI Mood State Resident Assessment Protocols |

Social engagement was positively associated with SHARP (P = .0001) and MIDAS scores (P = .0001) but inversely associated with mood state problems (P = .0002) |

| Jao, 2018 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=126) | Inclusion: diagnosis of dementia following Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and MMSE scores between 7 and 24 | Cohort | Social interaction, using the Passivity in Dementia Scale (PDS) | Affect, using the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Apparent Affect Rating Scale; 2 positive affect states (interest and pleasure) and 3 negative affect states (anxiety, anger, and sadness) were included | Social interaction was associated with higher interest and pleasure at within- and between-person levels (P < .001); increased social interaction significantly predicted higher sadness (P = .01) and anxiety (P < .001) at the within-person level; social interaction was not associated with anger |

| Kroemeke, 2016∗ | Poland | Nursing home residents (N=180) | Inclusion: no cognitive disorder (no diagnosis of dementia or mild cognitive impairments) | Cross-sectional (at baseline) and longitudinal (after 1 mo) | Social support (received and provided), using the Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS) | Positive affect, using 3 items (joy, satisfaction, and optimism) from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | In cross-sectional analysis, there was a significant positive relationship between providing and receiving support and positive affect; in longitudinal analysis, neither received support nor given support were associated with positive affect |

| Lee, 2017 | United States | Nursing home and assisted living residents (N=110) | Inclusion: diagnosis of dementia following Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and MMSE score < 24 | Cross-sectional | Social interaction, using observations of interaction between nursing staff and nursing home residents (verbal or nonverbal; positive, negative, or neutral) | Positive and negative emotional expressions, using observations | Verbal (P < .01) and verbal + nonverbal (P < .01) interactions were associated with positive emotional expressions; verbal + nonverbal (P = .01) interactions were associated with negative emotional expressions. Positive (P < .01) and neutral interactions (P < .01) were associated with positive emotional expression; neutral (P = .00) and negative interactions (P = .02) were associated with negative emotional expression |

| Sherer, 2001 | Israel | Nursing home residents (N=43) | Exclusion: Alzheimer's disease | Cross-sectional | Social network, using 25 open-ended questions about number of friends, whether they visit them, when, frequency of visits, duration, content of visits, what was good or bad about them, satisfaction from visits, and frequency of other communications | Morale, using the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Sub-Scales for agitation (anxiety and dysphoric mood), attitudes toward own aging, and lonely dissatisfaction | Number of friends had a positive association with attitudes toward aging (P < .05); meeting friends had a positive association with the 3 morale variables (P < .05); duration of visits was not related to morale levels |

| Anxiety (n=3 studies) | |||||||

| Ahmed, 2014∗ | Egypt | Geriatric home residents (N=240) | Exclusion: cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 25) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using a 3-item loneliness scale | Anxiety, using the Arabic version of the Hamilton Anxiety Scale | Loneliness often (OR 4.46, 95% CI 1.36-14.68; P = .014) was associated with anxiety but not loneliness sometimes OR 2.47, 95% CI 0.64-9.54; P = .19) |

| Drageset, 2013∗ | Norway | Nursing home residents (N=227) | Inclusion: “cognitively intact” [0.5 or less on the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR)] | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the revised Social Provision Scale (SPS): attachment, social integration, opportunity of nurturance and reassurance of worth | Anxiety, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | The social support subdimension of attachment was associated with less anxiety (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.94, 0.99; P = .019) |

| Keister, 2006∗ | United States | New nursing home residents (N=114) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Modified Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors assessing 4 dimensions of social support (informational, tangible, emotional, and integration support) | Anxiety, using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | One aspect of social support was positively associated with anxiety; as informational support increased, anxiety increased (P < .05) |

| Medication use (n=3 studies) | |||||||

| Foebel, 2015 | Canada | Long-term care residents (N=47,768) | None specified | Cohort | Social engagement, using RAI | New antipsychotic medication use, using RAI measure of drugs in the 7 d prior to assessment | Reduced social engagement associated with lower risk of new antipsychotic use (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.71-0.87; P < .001) |

| Hjaltadóttir, 2012∗ | Iceland | Nursing home residents (N=3694) | None specified | Not stated | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Hypnotic drug use, using RAI data on drug use for more than 2 d in past week | Compared to residents with higher social engagement, moderate (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93-1.22) and low (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80-1.06) social engagement not associated with hypnotic drug use |

| Saleh, 2017 | Canada | Newly admitted residents (N = 2639) | Inclusion: diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease or other dementias | Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Antipsychotic medication use, using RAI measure of drugs in the 7 d prior to assessment | Social engagement was associated with antipsychotic use when controlling for sociodemographic variables (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.82-0.90; P <.001) but association disappeared when controlling for health variables (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.97-1.00; P = .21) |

| Cognitive decline (n=2 studies) | |||||||

| Freeman, 2017 | Canada | Nursing home residents (N=111,052) | Included, results stratified by diagnosis of dementia | Cohort | Social engagement, using the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Cognitive performance, using the RAI Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) | Social engagement was protective against cognitive decline (P < .001), and more pronounced for residents without a diagnosis of dementia |

| Yukari, 2016 | Czech Republic, England, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, and the Netherlands | Nursing home residents (N=1989) | None specified | Cohort | Social engagement, using 7 items, similar to the RAI Index of Social Engagement (ISE) | Cognitive performance, using the RAI-MDS Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) | Lower social engagement associated with a greater cognitive decline; the greatest cognitive decline observed among socially disengaged residents with dual sensory impairment (1.87; 1.24:2.51). |

| Death anxiety (n=2 studies) | |||||||

| Azaiza, 2010 | Israel | Nursing home residents (N=65) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Social Support Scale | Death and dying anxiety, using 2 scales based on Carmel and Mutran (1997) | Higher social support was associated with lower death anxiety (P < .05) |

| Mullins, 1982 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=228) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social support, using subjective assessment of the extent of the social support the resident received from others | Death anxiety, using the Death Anxiety Scale | Among younger residents (age < 75 y), lack of social support associated with higher death anxiety |

| Boredom (n=2 studies) | |||||||

| Ejaz, 1997 | United States | Nursing home residents (N=175) | Inclusion: cognitively alert | Cross-sectional | Social engagement (inside the nursing home), using RAI-MDS variable for group activities that involve social interaction and time spent alone Social network (inside the nursing home), using the total number of people (residents and staff) to whom the resident felt close and friendship with other residents Social interaction (inside the nursing home), using positive interactions and negative interactions Social engagement (outside the nursing home), using variables for each of the number of visits from family and friends in past month |

Boredom, using interview item that asked subjects to rate how often they were bored in the nursing home | Negative social relationships associated with boredom (P < .01) |

| Slama, 2000 | United States | Veterans Home residents (N=35) | Inclusion: cognitively intact per Section B (Cognitive Patterns) of the Minimum Data Set (MDS) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale | Boredom, using question from Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Loneliness was correlated with boredom (P = .009) |

| Suicidal thoughts (n=2 studies) | |||||||

| Zhang, 2018 | China | Nursing home residents (N=205) | Exclusion: a diagnosis of “dementia” or moderate to severe cognitive deficit (MMSE score < 16 for participants with no formal education and a MMSE score <20 for primary school graduates or above) | Cross-sectional | Social support, using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Suicidal thoughts, using item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | In univariate analysis, those with suicide thoughts reported lower social support from family (P < .001), friends (P < .001), and significant others (P < .001); perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others moderated the relationship between physical health and suicidal thoughts |

| Zhang, 2017 | China | Nursing home residents (N=205) | Exclusion: a diagnosis of “dementia” or moderate to severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score < 16 for participants with no formal education and an MMSE score <20 for primary school graduates or above) | Cross-sectional | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale Social engagement, using the frequency of visits with their children, and the numbers of different types of social activities in which they engaged |

Suicidal ideation, using item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) | In univariate analysis, those who had higher loneliness, fewer visits from their children, and participated in fewer social activities all had higher suicidal ideation scores (P < .05); in path analysis, results suggest loneliness can impact suicidal ideation, mediated by depression and hopelessness; frequency of visits and engagement in social activities can also affect suicidal ideation (mediated by loneliness or self-esteem, respectively) |

| Psychiatric morbidity (n=1 study) | |||||||

| Andrew, 2005 | England | Care home residents (N = 2493) | None specified (but use of proxy respondents based on the results of a cognitive function screen) | Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using group participation Social support, using the Social Support Index (SSI) |

Psychiatric morbidity, using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), where scores ≥4 were taken to define a “case” of psychiatric morbidity, and scores <4 a “non-case” | Severe lack of social support associated with increased odds of psychiatric morbidity (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.05-2.52) but not moderate lack of social support (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.53-1.41); no association between group participation and psychiatric morbidity (OR 0.95, 95% 0.88-1.03) |

| Daily crying (n=1 study) | |||||||

| Palese, 2018 | Italy | Nursing home residents (N=8875) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Social engagement, using involvement in socially based activities | Daily crying, defined as the occurrence of at least 1 episode of crying daily over the last month | Residents involved in socially based activities were less likely to cry on a daily basis (OR 0.882, 95% CI 0.811-0.960) |

Study reports more than 1 mental health outcome.

Supplementary Table 2.

Summary of Studies Used to Address Question 2, Presented According to Strategy and Study Type (Observational or Intervention)

| 1. Manage Pain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | |||||||

| First Author, Year | Country | Population (N=) | Inclusion/Exclusion Related to Cognition | Study Design | Exposure | Social Outcome | Study Finding |

| Almenkerk, 2015 | The Netherlands | Nursing home residents with chronic stroke (N=274) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Pain, using Resident Assessment Instrument- Minimum Data (RAI-MDS) | Social engagement, using RAI-MDS Revised Index for Social Engagement (RISE) | Substantial pain was associated with low social engagement (OR 4.25, 95% CI 1.72-10.53; P < .05), but only in residents with no/mild or severe cognitive impairment; this relation disappeared adjusted for Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire score (OR 1.95, 95% CI 0.71-5.39) |

| Klapwijk, 2016 | The Netherlands | Nursing home residents with dementia (N=288) | Inclusion: moderate to very severe dementia, using the Reisberg Global Deterioration Scale (Reisberg GDS) 5-7 | Cross-sectional | Pain, using the Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC-D) | Social relations, using the QUALIDEM Social isolation, using the QUALIDEM |

In unadjusted analysis, pain was associated with social relations (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.83-0.94; P < .01) and social isolation (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.82-0.94; P < .01). Associations were no longer statistically significant in multivariable analysis. |

| Lai, 2015∗ | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=125) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Pain | Social relationships, using the WHOQOL-BREF | Pain associated with lower social relationships score (P < .001) |

| Lood, 2017 | Sweden | Nursing home residents (N=4451) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Pain, using the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale | Social engagement, using a list of study-specific items on participation (eg, going on an outing/excursion, having everyday conversations with staff not related to care) | Pain was correlated with less participation in social occupations (P < .01); however, it was no longer statistically significant in the adjusted model |

| Tse, 2013 | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=535) | Exclusion: mental disorder or cognitive impairment | Cross-sectional | Pain, using an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale | In unadjusted analysis, pain was not associated with loneliness (P = .557). |

| Tse, 2012 | Hong Kong | Nursing home residents (N=302) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Pain, using the Geriatric Pain Assessment | Loneliness, using the UCLA Loneliness Scale | In unadjusted analysis, pain associated with higher loneliness (P = .05). |

| Van Kooten, 2017 | The Netherlands | Nursing home residents (N=199) | Inclusion: diagnosis of dementia Exclusion: Parkinson disease dementia, alcohol-related dementia, cognitive deficits due to psychiatric disorders |

Cross-sectional | Pain, using the Mobilization Observation Behavior Intensity Dementia (MOBID-2) Pain Scale |

Social relations, using the QUALIDEM | The association between pain and social relations was not statistically significant for mild (P = .25) or moderate-severe pain (P = .25) |

| Won, 2006 | United States | Nursing home residents with persistent pain (N=10,372) | Exclusion: moderate to severe cognitive impairment based on a Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) score of >2 (equivalent of <19 in MMSE) | Cohort | Analgesic use, standing long-acting opioids (vs standing-acting opioids; standing nonopioids; and no analgesics) | Social engagement, using RAI-MDS Index of Social Engagement | Standing long-acting opioids (vs standing nonopioids) were associated with improvements in social engagement (propensity adjusted rate ratio 1.60; 95% CI, 1.02-2.48) |

| Intervention studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Author, Year | Country | Population (N=) | Inclusion/Exclusion Related to Cognition | Randomized (Yes/No) | Study Design | Intervention | Social Outcome | Study Finding |

| Chibnall, 2005 | United States | Nursing home residents with moderate-to-severe dementia (N=25) | Inclusion: moderate-to-severe dementia indicated by a stage 5 or 6 on the Functional Assessment Staging (FAST) | Yes | Randomized controlled trial, crossover | Analgesic medication, 4 weeks of acetaminophen (3000 mg/d) (vs placebo) | Social interaction (direct and passive social involvement), using Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) Social withdrawal, using DCM |

Acetaminophen intervention group exhibited significant increases in direct social interaction (P = .05) and passive social involvement (P = .006) |

| Husebo, 2019 | Norway | Nursing home residents (N=723) | None | Nursing homes randomized | Cluster-randomized controlled trial | Staff education and training on communication, systematic pain management, medication review, and activities (vs usual care) | Social relations, using the QUALIDEM Social isolation, using the QUALIDEM |

During the follow-up (month 4-9), there was an intervention effect for social relations (P < .05) |

| Tse, 2012 | China | Nursing home staff (N=147) and residents (N=535) | Exclusion: cognitive impairment and history of mental disorders | Nursing homes randomized | Cluster-randomized controlled trial | Integrated pain management program including a physical exercise program and multisensory stimulation art and craft therapy, 1 h/wk for 8 wk (vs usual care) | Loneliness, using the Chinese version of Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Intervention group showed significantly lower loneliness after the program (P < .001). There was no change in the control group. |

| Tse, 2013 | China | Nursing home staff (n=60) and residents (n=90) | Inclusion: oriented to time and place | Nursing homes randomized | Pretest-posttest (2 groups) | Integrated pain management program that included garden therapy and physiotherapy exercise for the residents, 1 h/wk for 8 wk (vs usual care) | Loneliness, using the Chinese version of Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale | Intervention group showed significant improvement in loneliness after the program (P < .05) but not in the control group |

| Tse, 2016 | China | Nursing home residents (N=50) | Inclusion: score ≥6 in the Abbreviated Mental Test. Exclusion: cognitive impairment or mental disorders | Nursing homes randomized | Pretest-posttest (2 groups) | Group-based pain management program that included physical exercise, interactive teaching and sharing of pain management education, 1 h twice per wk for 8 wk (vs usual care) | Loneliness, using the Chinese version of Loneliness Scale | Loneliness decreased in both intervention and control groups; no significant difference in loneliness between the 2 groups at baseline or week 12 |

| 2. Address Vision and Hearing Impairments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | |||||||

| First Author, Year | Country | Population (N=) | Inclusion/Exclusion Related to Cognition | Study Design | Exposure | Social Outcome | Study Finding |

| Achterberg, 2003 | The Netherlands | Newly admitted nursing home residents (N=562) | None specified | Cross-sectional | Vision impairment, using the Resident Assessment Instrument–Minimum Data Set 2.0 (RAl-MDS) Hearing impairment, using RAI-MDS |

Social engagement, using RAI-MDS Index of Social Engagement | Vision impairment associated with low social engagement (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.1-2.5; P = .011) but not hearing impairment (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.7-1.6; P = .85) |

| Bliss, 2017∗ | United States | New nursing home residents followed to 1 y (N=15,927) | None specified | Cohort | Vision impairment, using RAI-MDS | Social engagement, using RAI-MDS Index of Social Engagement 1 y after admission | Vision impairment associated with lower social engagement at 1-y follow-up (P < .001) |