Abstract

Tertiary lymphoid organs (TLOs) are collections of immune cells resembling secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) that form in peripheral, non-lymphoid tissues in response to local chronic inflammation. While their formation mimics embryologic lymphoid organogenesis, TLOs form after birth at ectopic sites in response to local inflammation resulting in their ability to mount diverse immune responses. The structure of TLOs can vary from clusters of B and T lymphocytes to highly organized structures with B and T lymphocyte compartments, germinal centers, and lymphatic vessels (LVs) and high endothelial venules (HEVs), allowing them to generate robust immune responses at sites of tissue injury. Although our understanding of the formation and function of these structures has improved greatly over the last 30 years, their role as mediators of protective or pathologic immune responses in certain chronic inflammatory diseases remains enigmatic and may differ based on the local tissue microenvironment in which they form. In this review, we highlight the role of TLOs in the regulation of immune responses in chronic infection, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, cancer, and solid organ transplantation.

Keywords: Tertiary lymphoid structures, Inflammation, Autoimmune diseases, Transplantation immunology, Tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Lymphoid organs can broadly be classified into three categories. Primary lymphoid organs develop during embryogenesis and include the bone marrow and thymus which are responsible for the production of lymphoid cells [1, 2]. Secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) regulate antigen-driven lymphocyte expansion resulting in production of memory T cells, effector B cells, and plasma cells and include lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils, Peyer’s patches of the gut, and certain mucosal lymphoid tissues that develop independent of antigen [1, 2]. While lymphoid organogenesis (SLO formation) generally occurs during embryogenesis, certain mucosal lymphoid tissues, including mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), nose-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT), and tear duct-associated lymphoid tissue (TALT), develop after birth [2–4]. TLOs, also known as tertiary lymphoid tissues, tertiary lymphoid structures, or ectopic lymphoid structures, are collections of immune cells that resemble secondary lymphoid organs organized into a follicular structure, often with germinal centers, that form in peripheral, non-lymphoid tissues in response to chronic inflammation or tissue injury [2, 5, 6]. While the signaling pathways involved in the formation and maintenance of TLOs generally mimic SLO formation, TLOs regulate immune responses in a disease- and tissue-specific manner, and thus can lead to protective or pathologic responses depending on the tissue microenvironment in which they form [2, 7, 8]. These structures have proven to be critical for the regulation of immune responses in the periphery in several chronic inflammatory conditions. In this review, we highlight the role of TLOs in the regulation of immune responses in chronic infection, chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, cancer, and solid organ transplantation.

Formation of TLOs

TLOs are formed at sites of chronic inflammation or tissue injury in a process known as lymphoid neogenesis (Fig. 1) [2, 6, 9, 10]. The structure of TLOs can vary depending on inflammatory stimulus and tissue type from clusters of B and T lymphocytes to structures organized in a manner similar to SLOs with B cell follicles and germinal centers, T cell compartments, LVs, and HEVs, but generally lack a defined capsule [2, 6, 11, 12]. Unlike lymphoid organogenesis which is programmed, lymphoid neogenesis is inducible and occurs in response to local inflammation [2, 4, 6, 13]. However, while lymphoid neogenesis has largely been shown to follow similar signaling pathways as lymphoid organogenesis, the events precipitating TLO formation have not been fully elucidated and may differ by disease process and tissue of origin [2, 5, 14].

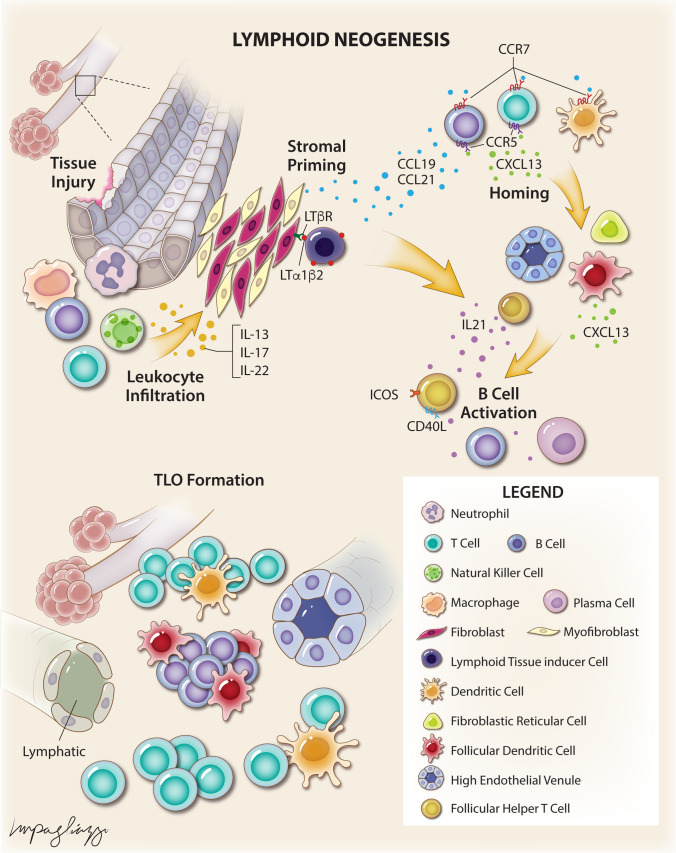

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustrating mechanisms of lymphoid neogenesis

Local inflammatory responses to tissue injury trigger secretion of cytokines, such as IL-13, IL-17, and IL-22, by infiltrating immune cells and resident fibroblasts resulting in priming of local stromal cells, including fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and endothelial cells [9, 15, 16]. The immune cells that produce this signal can differ based on the inflammatory stimulus and the tissue in which the inflammation occurs [9, 17, 18]. These signals result in local fibroblast proliferation and expression of lymphoid stromal chemokines, such as CXCL13, CCL19, and CCL21 [9]. CXCL13 is a chemokine that binds to the CXCR5 receptor on B cells and subsets of T cells and is critical for the homing of these cells and structural organization of lymphoid organs [19]. CCL19 and CCL21 are chemokines that bind the CCR7 receptor on B and T lymphocytes as well as dendritic cells (DCs) and are critical for the trafficking of these cells into lymphoid organs [20]. Expression of these chemokines by local fibroblasts results in recruitment of immune cells and further expression of chemokines (CXCL13, CCL19, CCL21) and cytokines (IL-17, IL-22). In addition, infiltrating immune cells and lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells can express cytokines from the TNF superfamily such as TNF-α, lymphotoxins [LTα (also known as TNF-β), LTα1β2, LTα2β1)], and lymphotoxin-like inducible protein that competes with glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry on T cells (LIGHT) [21, 22]. LTα1β2 and LIGHT can bind and activate the lymphotoxin β receptor (LTβR) on stromal cells. LTβR signaling mediates the differentiation of fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) and follicular dendritic cells (FDCs), formation of HEVs, and organization of B and T lymphocyte compartments [23]. In addition, production of TNF-α by M1 macrophages has been shown to induce aortic TLOs in a LTβR-independent fashion in a murine model of atherosclerosis. These signaling cascades result in a positive feedback loop wherein more immune cells are recruited and chemokine and cytokine production increase. As more immune cells are recruited, localization of CXCL13 and CCL21 expression can result in separate B and T cell compartments [24, 25]. LVs and HEVs form and express CCL21 which may allow naïve B and T lymphocytes to enter the TLO [11]. While lymphangiogenesis in TLOs remains poorly understood, studies have implicated LTβR signaling, differentiation of peri-venular and preexisting LV endothelial cells, and even transdifferentiation of macrophages in this process [11]. FDCs produce CXCL13 in B cell compartments and recruit follicular helper T (TFH) cells to form functional germinal centers [26]. TFH cells secrete IL-21, a B cell stimulatory cytokine, and express costimulatory signals including inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS) and CD40L which together result in B cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation into antibody-producing plasma cells [27–29]. Sustained signaling by CD11c+ DCs appears to be critical to the maintenance and function of these structures as selective depletion of these cells in murine models of TLO formation results in dissolution of TLOs [30, 31].

One of the major unresolved issues in TLO biology is whether TLO formation always occurs due to an antigen-dependent immune response. Antigen-dependent immune responses have been implicated in the formation of TLOs in human and animal models of certain conditions, including microbial antigens in infection and vaccination [32], the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis [33], multiple thyroid antigens in autoimmune thyroiditis [34], tumor-associated antigens in malignancy [35], and alloantigens after transplantation [36]. However, TLOs have been observed to form in conditions in which the driving antigen is not readily apparent, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [37] and atherosclerosis [38]. In addition, Fleig and colleagues recently showed in a mouse model that loss of endothelial Notch signaling alone can induce perivascular TLO formation indicating that these structures can form in an antigen-independent fashion [39]. These observations have led to the development of the inflammation-driven TLO hypothesis (as coined by Yin and colleagues) in which TLO formation occurs due to signaling cascades induced by chronic, un-resolving inflammation in an antigen-independent manner [40].

Role in infection and chronic inflammation

TLOs can form as a protective immune response during infection with certain bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens. Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTb) results in granuloma formation followed by infiltration of immune cells and their organization into TLOs known as inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in both humans and animal models [41–43]. Formation of iBALT is associated with IL-17, IL-22, IL-23, CXCL13, CCL19/CCL21, and CCR5 signaling in animal models of MTb infection [42, 44–47]. iBALT may play an important role in the control of MTb infection given its presence in patients with latent TB and absence in patients with reactivated TB [48]. In addition to bacteria, iBALT has shown similar protective immune responses to fungal and viral pathogens. In a mouse model of Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, iBALT formation was dependent on CXCL13 and resulted in a reduced fungal burden [49]. In animal models of influenza virus infection, iBALT formation results in improved viral clearance and reduced mortality [8, 50–52]. Also, induction of BALT with virus-like particles results in improved viral clearance in influenza-naïve mice [53]. Vaccine strategies that induce BALT have been shown to elicit effective immune responses to bacterial and viral pulmonary pathogens in animal models [54–56]. These studies illustrate that TLOs can play a protective role during infection with certain bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens.

TLOs have also been implicated in facilitating pathologic immune responses to certain infectious pathogens. iBALT has been shown to induce hypersecretion of mucus, exacerbate inflammation, and induce asthma exacerbation in mouse models of respiratory syncytial virus infection [57, 58]. iBALT has also been found in humans and animal models of cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis where chronic infection with bacterial pathogens is common, though their role as protective or pathologic structures is poorly understood [59, 60]. Animal models of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection show iBALT formation is dependent on IL-17 production and results in production of anti-Pseudomonal IgM and IgA antibodies, but can also result in narrowing of small airways potentially contributing to obstructive lung diseases in which chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection is common [61–63]. Human peptic Helicobacter pylori infection results in development of ectopic MALT in the gastric mucosa and is associated with gastritis and development of MALT lymphoma [64–66]. TLOs have further been associated with pathologic immune responses to infectious pathogens in the liver (Propriobacterium acnes, Helicobacter hepaticus, hepatitis C virus), kidney (Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona), synovium (Borrelia burgdorferi), and central nervous system (Borrelia burgdorferi) in humans and animal models [67–75].

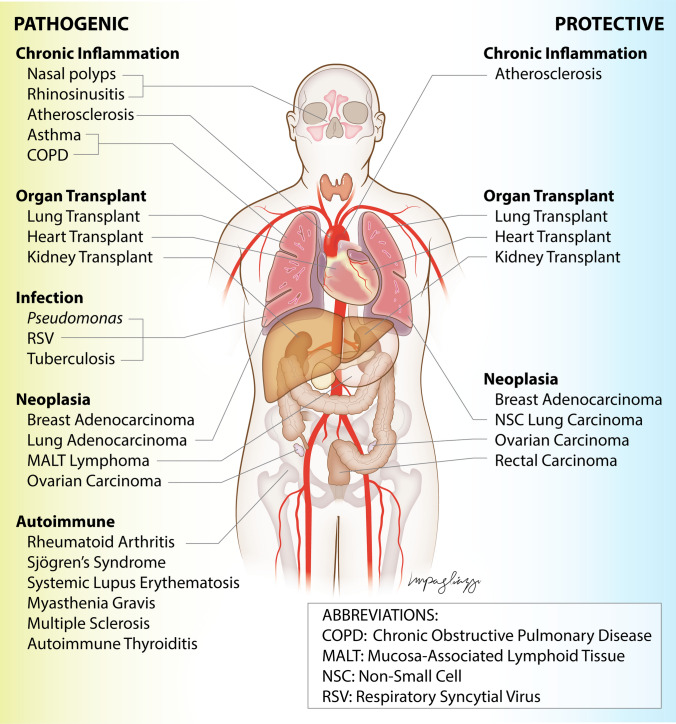

TLOs can also propagate pathologic immune responses in chronic inflammatory diseases. Formation of iBALT is associated with vascular inflammation in humans and animal models of pulmonary hypertension [76, 77] and airway inflammation associated with asthma and COPD [78–83]. TLO formation results in mucosal inflammation and nasal polyp formation in human chronic rhinosinusitis [84–87]. CXCL13 and CCL21 have also been implicated in bowel mucosal TLOs and mesenteric fat inflammation in humans and animal models of inflammatory bowel disease [88–93]. Interestingly, TLOs have been shown to promote vascular inflammation in some human studies and animal models of aortic atherosclerosis but prevent atherosclerosis and plaque rupture in others [23, 94–97]. Collectively, these studies point to disease- and tissue-specific roles of TLOs in mediating protective or pathologic responses in chronic inflammatory diseases (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Schematic showing tissue- and disease-specific roles of TLOs in regulating pathogenic or protective immune responses

Table 1.

Summary of the tissue- and disease-specific roles of TLOs in regulating peripheral immune responses

| Condition | Location | Species | Role | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoimmune disease | ||||

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | Thyroid | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [34, 102, 111] |

| Diabetes mellitus, type I | Pancreas | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [21, 22, 101] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Meninges | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [15, 16, 18] |

| Myasthenia gravis | Thymus | Human | Pathologic | [33, 119] |

| Myositis | Muscle | Human | Pathologic | [109, 110] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Synovium, lung | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [24, 90, 91, 98, 103, 104, 112–114, 116, 120–124, 128, 131–134, 136–139] |

| Sjogren syndrome | Salivary gland | Human | Pathologic | [25, 29, 99, 105, 106, 115, 118, 125–127, 129, 130, 135, 140, 141] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Kidney | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [100, 107, 108] |

| Chronic inflammatory disease | ||||

| Asthma | Lung | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [78, 79] |

| Atherosclerosis | Artery | Human, mouse | Both | [23, 38, 39, 94–97] |

| Bronchiectasis | Lung | Human, mouse | Unknown | [59] |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Lung | Human, mouse | Pathologic | [37, 80–83] |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | Nasal mucosa | Human | Pathologic | [84–87] |

| Cystic fibrosis | Lung | Human, mouse | Unknown | [59, 60] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Intestinal mucosa | Human | Pathologic | [88–93] |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | Lung | Human, rat | Pathologic | [76, 77] |

| Infection | ||||

| Borrelia burgdorferi | Synovium, central nervous system | Human, Rhesus macaque | Pathologic | [73–75] |

| Francisella tularensis | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [32] |

| Helicobacter hepaticus | Liver | Mouse | Pathologic | [68] |

| Helicobacter pylori | Gastric/duodenal mucosa | Human | Pathologic | [64–66] |

| Hepatitis C virus | Liver | Human | Pathologic | [69–71] |

| Influenza virus | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [30, 50–53, 56] |

| Leptospira interrogans serovar Pomona | Kidney | Pig | Pathologic | [72] |

| Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [61] |

| Mouse-adapted SARS coronavirus | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [56] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Lung | Human, mouse | Protective | [41–48, 54, 55] |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [49] |

| Pneumovirus of the mouse | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [56] |

| Propionibacterium acnes | Liver | Mouse | Pathologic | [67] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Lung | Mouse, rat | Unknown | [62, 63] |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Lung | Mouse | Protective | [57, 58] |

| Malignancy | ||||

| Bladder cancer | Intratumoral | Human | Protective | [176, 177] |

| Breast cancer | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human | Both | [27, 35, 144, 146, 147, 151, 159, 165, 173, 174] |

| Colorectal cancer | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human | Both | [142, 158, 167, 168] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human, mouse | Both | [148, 152, 153, 170] |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human | Both | [163] |

| Lung cancer | Intratumoral | Human, mouse | Both | [145, 154, 157, 178] |

| Melanoma | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human, mouse | Both | [143, 155, 156, 160, 166, 175] |

| Ovarian cancer | Intratumoral | Human | Protective | [150, 161, 162] |

| Pancreatic cancer | Intratumoral, peritumoral | Human | Both | [164, 169] |

| Transplantation | ||||

| Heart transplantation | Heart | Human, mouse | Both | [36, 181–183, 185, 186, 199] |

| Kidney transplantation | Kidney | Human, mouse | Both | [36, 199, 202–205] |

| Lung transplantation | Lung | Human, mouse, rat | Both | [36, 194–198, 200, 201] |

Role in autoimmune disease

TLOs have been observed in the target tissues of several autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis [98], Sjögren’s syndrome [99], systemic lupus erythematosus [100], myasthenia gravis [33], type I diabetes mellitus [101], autoimmune thyroiditis [34, 102], and multiple sclerosis [18]. While TLOs have been observed in the majority of autoimmune diseases, their prevalence varies widely in published reports, both among diseases and even within populations having a particular autoimmune disease [98, 103–111].

Autoimmune disease-associated TLOs are theorized to develop in response to disease-specific autoantigens in the target tissues and result in local autoantibody production [112]. The events that trigger the release of autoantigens in the formation of TLOs remain elusive. Prior studies have implicated viral infections, stromal cell antigen release, and cell death pathways, with a particular focus on the production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), or NETosis [112–115]. Regardless of the source of autoantigens, autoimmune disease-associated TLOs can develop functional germinal centers that express activation-induced cytidine deaminase (the enzyme implicated in immunoglobulin gene affinity maturation by somatic hypermutation and isotype class switch recombination) resulting in proliferation of B cell clones and their differentiation into plasma cells that produce autoantibodies against local autoantigens [98, 113, 116]. Furthermore, autoimmune disease-associated TLOs allow germinal center entry of autoreactive B cells whereas they are excluded from entry into germinal centers in SLOs [117, 118].

The development of TLOs in autoimmune disease can result in sustained immune activation and production of autoantibodies. Transplantation of TLO-containing tissues from patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren’s syndrome into severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice resulted in production of human anti-citrullinated peptide antibody or human anti-SSA (anti-Ro) and anti-SSB (anti-La) antibodies, respectively [98, 115]. In addition, transplantation of thymic tissue fragments, but not dissociated thymic cells, from patients with myasthenia gravis into SCID mice resulted in sustained production of human anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies [119]. These studies illustrate the importance of the structural organization of autoimmune disease-associated TLOs to the maintenance of autoantigen-directed responses.

The presence of TLOs has been associated with variable disease severity and clinical outcomes in autoimmune diseases [5, 12]. While some reports in rheumatoid arthritis patients show no effect on disease severity [104, 120], others have shown an association between TLO formation and increased autoantibody and inflammatory cytokine production along with more erosive disease [121–124]. In patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, the presence of TLOs is associated with increased autoantibody and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, clinical disease severity, and risk of development of lymphoma [125–127]. TLOs can also be found in the lungs (BALT) of patients with pulmonary involvement of rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren’s syndrome [128]. These TLOs are associated with increased expression of CXCL13, CCL21, ICOSL, and lymphotoxin and correlate with tissue damage and fibrosis in the lungs of patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease [128]. The role of TLOs in clinical disease severity is less well established in other autoimmune diseases. Thus, autoimmune disease-associated TLO formation affects clinical severity in a disease- and tissue-specific manner.

The sustained immune activation associated with TLO formation may have implications for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Sjögren’s syndrome have shown conflicting results regarding the role of TLOs in clinical responses to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) including rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody), abatacept (CTLA4-Ig fusion protein, co-stimulatory signal inhibitor), and anti-TNF therapies [129–135]. Studies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis show that treatment with rituximab is associated with elimination of circulating B cells and reduction in circulating anti-rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies [136–138]. However, rituximab treatment has been shown to deplete but not eliminate synovial B cells, especially those found in lymphoid aggregates, and does not affect synovial autoantibody production suggesting that TLOs in rheumatoid arthritis may serve as a protective niche for autoreactive B cells [132, 136, 137, 139]. Furthermore, non-responders to rituximab treatment were more likely to have residual synovial plasma cells along with higher levels of CXCL13 and B cell repopulation [131, 136, 138]. Similarly, studies have shown that rituximab significantly reduces systemic B cell biomarkers but does not affect clonal expansion of autoantibody-producing cells in salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome, and does not affect parotid enlargement or tissue expression of B cell-activating factor (BAFF) in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome-associated MALT lymphoma [140, 141]. These findings have led to a focus on therapies that target signals critical to TLO formation and maintenance including IL-17, IL-21, lymphotoxin, ICOS-ICOSL, CD40-CD40L, and BAFF [5, 12]. Thus, autoimmune disease-associated TLOs play a role in the maintenance of peripheral immune responses.

Role in cancer

The microenvironment of tumorigenesis shares similarities to that of chronic inflammation due to the constant infiltration of immune cells, providing an inflammatory milieu for tumor progression and metastasis. Active recruitment of lymphocytes to tumor-associated TLOs (TA-TLOs) has been demonstrated in humans and preclinical mouse models of colorectal cancer [142]. Additionally, TA-TLOs have been shown to drive oligo-clonal B cell responses as well as T cell priming and expansion in animal models of breast cancer and melanoma [35, 143]. However, the precise mechanisms regulating TA-TLO formation remain unknown. Many of the cytokines and lymphoid chemokines associated with TA-TLOs (e.g., CCL21, CXCL13, TNF-α) are shared with other non-neoplastic inflammatory processes. Similar to chronic infections and inflammatory diseases, the presence of TLOs in solid, non-lymphoid tumors has been associated with variable outcomes [142, 144–149]. The role of TA-TLOs in promoting pro- or anti-tumoral immune responses is disease-specific and likely depends on a variety of factors including cellular composition and location (intra-tumoral vs peri-tumoral).

TA-TLOs can be enriched in regulatory T cells (Tregs) that can inhibit anti-tumor responses and promote tumor growth. Tumor infiltration by Tregs has been associated with worse prognosis in various types of cancer [146, 150–153]. In patients with ovarian carcinoma, tumor-associated Tregs suppressed tumor-specific T cell immunity to promote the growth of human tumors in vivo [150]. Similarly, a study utilizing a genetically engineered mouse lung adenocarcinoma model showed that tumor bearing mice have a significant increase in tissue-infiltrating Tregs accumulating in TA-TLOs compared with controls [154]. These Tregs can suppress anti-tumor responses by modulating interactions between T cells and DCs [154]. Notably, depletion of Tregs enhanced DC costimulatory ligand expression and resulted in the increased proliferation of T cells, stimulating tumor destruction. Related findings have been demonstrated in studies of patients with breast cancer, which showed that high numbers of Tregs within TA-TLOs, rather than in the tumor bed, are predictive of relapse and death [146]. In contrast to other T cells, Tregs were found to be selectively activated locally with proliferation in situ, resulting in suppression of effector T cell activation, immune escape, and tumor progression. While the complex regulatory mechanisms and function of tumor-associated Tregs remain to be elucidated, inhibition of these responses may serve as a potential therapeutic target to promote adaptive anti-tumor immune responses.

While Tregs inhibit anti-tumoral responses in TA-TLOs, other T cell subsets, along with DCs and B cells, promote anti-tumoral immune responses. Previous studies utilizing mouse models which lack lymph nodes demonstrated that effective T cell priming can occur locally at the tumor site [143, 155]. TLO induction within the tumor in a murine model of metastatic melanoma has been shown to provoke naïve T cell infiltration and differentiation, which is associated with the generation of tumor-specific T cells [156]. Additionally, the density of mature DCs in TA-TLOs is highly associated with a strong and coordinated Th1 and cytotoxic T cell response in patients with non-small cell lung cancer [157]. TA-TLOs enriched in DCs and CD8+ T cells are associated with improved survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and rectal cancer [157, 158]. Higher density of DC and CD4+ TFH cell infiltration in TA-TLOs in breast cancer patients was associated with higher rates of metastasis- and disease-free survival [27, 159]. In addition, B cells in TA-TLOs have been implicated in anti-tumor responses in patients with melanoma and ovarian cancer [160, 161]. B cell follicles within TA-TLOs may serve as a site for the local generation of humoral immunity against tumor antigens. In a study of human non-small cell lung cancer, germinal centers within tumors exhibited activated somatic hypermutation and class switch recombination, which was associated with antibody reactivity against tumor antigens [145]. In addition, a high density of follicular B cells within TA-TLOs correlated with long-term survival [145]. In a study of patients with serous ovarian cancer, tumor-associated B cells produced polyclonal IgA that was able to bind receptors universally expressed on ovarian cancer cells, sensitizing tumor cells to cytolytic killing by T cells and hindering malignant progression [162]. Taken together, these findings suggest that specific immune cells in TA-TLOs can be key regulators of local adaptive immune responses at the tumor site.

TA-TLOs can be found within the tumor (intra-tumoral) or outside the tumor margin (peri-tumoral) and their specific location may be predictive of immune responses to the tumor. While the presence of intra-tumoral TLOs has been associated with anti-tumoral responses, peri-tumoral TLOs have been associated with pro-tumoral responses and worse clinical outcomes in certain solid tumors. Peri-tumoral TLOs were associated with worse overall survival compared with intra-tumoral TLOs in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic ductal carcinoma [163, 164]. In breast cancer patients, peri-tumoral TLOs were associated with higher-grade tumors and reduced disease-free and overall survival [165]. Melanoma metastases were more likely to have peritumoral TLOs than primary melanoma tumors [166], and in colorectal cancer patients, peritumoral TLOs were associated with advanced disease, tumor progression, and worse prognosis [167]. However, introduction of Helicobacter hepaticus into the intestinal tract in a mouse model of colorectal cancer resulted in development of peritumoral TLOs and increased immune infiltration and tumor control [168]. The presence of peritumoral TLOs was also associated with a favorable prognosis in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [169], and with improved overall and relapse-free survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma [170]. While the precise mechanisms by which peritumoral TLOs promote pro-tumoral responses remain unknown, animal models have suggested that TLOs may provide a supportive niche for tumor progenitors and could provide a route for cancer dissemination through HEVs [148, 171, 172]. These findings suggest that the location of TA-TLOs may influence the type of immune responses generated and affect clinical outcomes in a disease-specific fashion.

The presence of TA-TLOs may also impact response to various forms of antineoplastic treatment. Studies in patients with breast cancer have shown that TA-TLOs predict a favorable response to chemotherapy alone and in combination with the HER2-targeting monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab [27, 173, 174]. In addition, TA-TLOs were shown to predict long-term survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy [145]. Furthermore, TA-TLOs have been implicated in responses to cancer immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. The presence of TA-TLOs in biopsy specimens from patients with melanoma was associated with increased survival after treatment with immune checkpoint blockade [175], and the presence of TA-TLOs and expression of CXCL13 were associated with response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer [176]. Moreover, immunotherapy may induce tumor regression by induction of TA-TLOs. As an example, a study of immunotherapy for loco-regionally advanced urothelial carcinoma found no association between the presence of TA-TLOs at baseline and treatment response; however, complete response was associated with a significant increase in TA-TLOs [177]. Additionally, a post hoc analysis of a clinical trial of neoadjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy showed that responders were significantly more likely to develop TLOs in the tumor regression bed [178]. While these studies suggest a correlation between the development of TA-TLOs and response to immunotherapy, the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain elusive. In a study of melanoma treatment with immune checkpoint inhibition, patients who responded to treatment demonstrated significantly different B cell marker expression compared to non-responders in a single-cell and bulk RNA analysis [179]. Corroborating these findings using a computational method to estimate the immune composition in patients with melanoma and renal cell carcinoma who were treated with immune checkpoint blockade, clonal B cells were found to be localized within TA-TLOs, and switched memory B cells were enriched in tumors of responders. These findings have sparked interest in therapies that can induce TLO formation in immunotherapy-resistant neoplasms. As an example, LIGHT-VTP fusion protein (targets LIGHT to angiogenic tumor vessels using a vascular targeting peptide) therapy triggers TA-TLO formation and improves survival when combined with immunotherapy in a mouse model of immunotherapy-resistant tumor formation [180]. While these data suggest induction of TA-TLOs may improve responsiveness to immunotherapy in resistant tumors, mechanisms underlying these phenomena remain unclear. It is evident that TA-TLOs have a significant impact on the neoplastic microenvironment and clinical outcomes, and understanding these molecular determinants will help provide key insights into the dynamic interactions between the immune system, tumor progression, and response to treatment.

Role in solid organ transplantation

Transplantation remains the only therapeutic option for many patients who develop end-stage organ failure. The clinical practice of organ transplantation consists of surgically transferring an organ from a donor of the same species who is genetically different from the recipient. Both innate and adaptive immune responses are mounted in response to the allograft, as well as to other injurious events which may accompany the transplantation procedure (e.g., release of endogenous ligands during inflammation associated with ischemia–reperfusion injury). These immunologic processes provide an environment of chronic inflammation which may facilitate the ectopic organization of lymphoid cells within the graft tissue.

Evidence of TLO formation in transplanted solid organs was first reported in cardiac allografts in 1985 as aggregates of structured lymphoid cells located within the endocardium of allografts, which were termed “Quilty lesions” [181]. These lesions, composed of B lymphocytes, T lymphocytes, macrophages, FDCs, and HEVs were initially attributed to viral infections or cyclosporine therapy as triggers for their formation [182]. However, these associations were subsequently called into question by studies which demonstrated an absence of endocardial lesions in other patients treated with cyclosporine, as well as lesion formation in myocardial biopsies with negative viral genomic testing [183, 184]. Thus, it was suggested that Quilty lesion formation was potentially linked to rejection. Conversely, recent findings have suggested that Quilty lesions may play a protective role in cardiac allografts [185]. To this end, 42 human cardiac allograft biopsies were evaluated for the presence of Quilty lesions and histologic findings of rejection, and results showed that the presence of Tregs and TGF-β+ cells within Quilty lesions was associated with higher rates of cardiac allograft acceptance [185]. In a study conducted by Baddoura in 2005, examination of 319 murine cardiac transplants revealed lymphoid neogenesis in 25% of allografts and the presence of these structures was generally associated with acute or chronic rejection [186]. While it remains unclear how TLO formation in cardiac allografts may impact alloimmunity and graft acceptance, understanding the local immune interactions within a transplanted heart will clarify potential avenues for developing novel therapeutic strategies to prolong graft survival.

Lung allografts have been considered one of the most highly immunogenic solid organ transplants due to their major role in host defense and prominent intrinsic lymphoid network with constant exposure to aerogenous antigens. BALT has been detected in healthy lungs of rabbits, rats, and guinea pigs, but its presence in human lungs appears to vary according to age [187, 188]. While BALT can be demonstrated in 50% of healthy infants and young children, the frequency of BALT in normal lungs of healthy human adults remains controversial with estimates ranging from 0 to 64% [189–193]. BALT was initially targeted as a possible explanation for the relatively high rate of rejection among lung allografts compared to other solid organ transplants. To further delineate to what extent rejection of lungs differs from that of other organs, Prop studied functional rejection of rat lung allografts and found that lymphocytes that resided in the BALT of donor lungs were associated with an accelerated rate of lung allograft rejection [194]. Interestingly, this was abrogated by donor irradiation prior to transplantation or by re-transplantation from a cyclosporine-treated intermediate host, suggesting that BALT that is present in donor lungs may serve as a trigger for rejection. A study of 77 trans-bronchial biopsies in human lung transplant recipients by Hasegawa’s group found that BALT was induced after transplantation and found no association of BALT with high-grade acute cellular rejection or development of bronchiolitis obliterans [195]. We have made the surprising observation that BALT is induced in tolerant lung allografts, a process that is dependent on IL-22 production by graft-infiltrating γδ T cells and type 3 innate lymphoid cells; interestingly, the iBALT is enriched in Tregs [196, 197]. Subsequent studies have shown that potentially deleterious humoral immune responses are regulated through Tregs that are present in the BALT of tolerant lungs [198]. In addition to chronic stimulation by alloantigen, lymphatic disruption may contribute to BALT formation [13, 199]. In a study utilizing a mouse lung transplant model, Reed demonstrated that transplantation of lungs with obstructed forward flow of pulmonary lymphatics (via C-type lectin domain family 2 (CLEC2) deficiency or ablation of lymphatic endothelial cells) resulted in spontaneous formation of lymphoid aggregates within the lung grafts [200]. Interestingly, although lymphatic function was globally impaired in CLEC2-deficient mice, TLOs were observed specifically within the lungs and were absent in other tissues with a similar magnitude of lymphatic loss as that of the lung, such as the mesentery and intestine, and this effect was independent of transplantation. These findings suggest that lymphatic disruption may play a major role in the induction of TLOs in lung allografts following transplantation. Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that lymphatic egress of Tregs from TLOs within tolerant lung allografts can downregulate immune responses systemically [201]. Thus, intra-graft TLOs appear to serve both beneficial and deleterious roles in lung transplantation and may regulate immune responses within and outside of the graft.

Organized lymphoid structures in renal allografts were reported in 2004 when 35 human renal transplant biopsies and explants from acutely rejecting grafts were evaluated for lymphatic vessel distribution in relation to immune infiltrates [202]. Such grafts were found to have perilymphovascular nodular infiltrates which contained highly proliferative T and B lymphocytes and were densely associated with newly formed lymphatic vessels. The authors speculated that lymphangiogenesis could contribute to the transport of infiltrating immune cells and alloreactive responses. A study by Thaunat reported an association between the presence of TLOs in renal grafts and chronic rejection [199]. A deleterious role for TLOs in renal allografts was the prevailing view until 2011 when the induction of TLO formation was reported in tolerant mouse kidney allografts [203]. In this study, Brown demonstrated that TLOs formed in tolerant renal allografts and the presence of intra-graft TLOs was associated with superior graft function. This was further supported by a study by Miyajima utilizing a mouse kidney transplant model with identification of nodular infiltrates rich in Tregs that were present in spontaneously accepting allografts [204]. Rosales subsequently demonstrated that systemic depletion of Tregs prompted dissolution of these renal lymphoid infiltrates and abolition of tolerance, raising the possibility that Treg-rich structures within grafts may contribute to kidney allograft acceptance [205]. These findings correlate with our findings that graft-resident Tregs residing in the BALT of tolerant lung allografts downregulate local alloimmune responses. In summary, TLO formation within donor organ grafts has been associated with both rejection and tolerance. While traditional dogma suggested that intra-graft TLOs propagate deleterious immune responses, recent data have shown that TLO formation may also play an essential role in modulating graft acceptance.

Future directions

Despite major advancements in understanding the pathways that govern the formation of TLOs, major gaps remain regarding the role they play in regulating peripheral immune responses. Given the reported diversity of both their structure and composition, the establishment of criteria to standardize the staging of TLOs in various disease processes is necessary. While classification systems have been proposed in individual disease processes and model systems, standardized criteria for TLOs in human disease are lacking [10, 36, 206–208]. Establishment of such criteria is important to identify the cell types and signaling pathways required for TLO formation in each disease state and tissue. In addition, such criteria may help reveal structures or cellular components associated with protective or pathologic responses. Indeed, understanding the components making TLOs protective or pathologic in a particular disease process is critical to the identification of targets for pharmacologic intervention. Pharmacologic disruption of pathologic TLOs is an active area of investigation in autoimmune disease, as TLOs have largely been associated with the propagation of autoimmunity and worse clinical outcomes in this realm [5, 12, 208]. Pharmacologic disruption of pathologic TLOs may prove useful in other chronic inflammatory diseases, some forms of solid organ transplant rejection, and as an adjunct to chemo- and immunotherapies in certain malignancies. Furthermore, the identification of signaling pathways leading to the development of protective TLOs is paramount for the development of antineoplastic therapies for some cancers and the development of tolerance after solid organ transplantation. To this end, understanding signaling pathways inducing protective responses may allow the modification of donor organs with ex vivo organ perfusion to set the stage for tolerogenic TLOs. One major challenge in the development of pharmacologic therapies to induce or disrupt TLOs will be route of administration, as systemic therapies could result in unwanted effects in SLOs and other tissues. Thus, the utilization of strategies to localize pharmacologic agents, such as with aerosolized delivery for lungs or nanoparticle delivery targeted at specific tissues, may be necessary. Delineating the requirements for immune cell trafficking entering and exiting TLOs, for example via HEVs, interstitial tissue migration, or lymphatics, may aid with the development of targeted therapeutic approaches for specific disease processes. Finally, future studies should focus on whether the formation of TLOs in a particular disease process is dependent on antigen-driven immune responses or can occur in an antigen-independent fashion, as understanding the factors driving TLO formation could improve strategies to develop targeted therapies to manipulate TLOs in disease.

Conclusion

TLOs have been identified as critical mediators of local disease- and tissue-specific immune responses in chronic inflammatory diseases and organ transplantation. While our understanding of the development and function of these structures has improved significantly over the last 30 years, their role in mediating protective or pathologic immune responses in certain disease processes remains elusive. Future studies should further delineate the role of TLOs in regulating immune responses in infection with certain pathogens, chronic inflammatory diseases, autoimmune diseases, cancer, and solid organ transplantation. Investigation in these areas may provide valuable insight into the mechanisms of disease progression, reveal novel therapeutic targets, and possibly identify biomarkers that predict progression of disease and response to treatment.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anita Impagliazzo for the medical illustrations.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the manuscript. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AB and HS and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

DK is supported by National Institutes of Health grants 1P01AI116501, R01HL094601, R01HL151078, The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. ASK is supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AI145108, I01BX002299 and P01AI116501. AB is supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5T32HL007317-44.

Availability of data and materials

The data and material that support this review are available in the published literature and referenced in the references section.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required for the preparation and publication of this review.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that no consent to publish is required as all data reviewed were from published literature and no individual human research participants were involved in this review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pabst R. Plasticity and heterogeneity of lymphoid organs. What are the criteria to call a lymphoid organ primary, secondary or tertiary? Immunol Lett. 2007;112:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruddle NH. Basics of inducible lymphoid organs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2020;426:1–19. doi: 10.1007/82_2020_218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Pavert SA, Mebius RE. New insights into the development of lymphoid tissues. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:664–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Randall TD, Mebius RE. The development and function of mucosal lymphoid tissues: a balancing act with micro-organisms. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:455–466. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bombardieri M, Lewis M, Pitzalis C. Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:141–154. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gago da Graça C, van Baarsen LGM, Mebius RE. Tertiary lymphoid structures: diversity in their development, composition, and role. J Immunol. 2021;206:273–281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2000873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shipman WD, Dasoveanu DC, Lu TT. Tertiary lymphoid organs in systemic autoimmune diseases: pathogenic or protective? F1000Res. 2017;6:196. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10595.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyron-Quiroz JE, Rangel-Moreno J, Kusser K, et al. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med. 2004;10:927–934. doi: 10.1038/nm1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nayar S, Campos J, Smith CG, et al. Immunofibroblasts are pivotal drivers of tertiary lymphoid structure formation and local pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:13490–13497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905301116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo S, Zhu R, Yu T, et al. Chronic inflammation: a common promoter in tertiary lymphoid organ neogenesis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2938. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruddle NH. Lymphatic vessels and tertiary lymphoid organs. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:953–959. doi: 10.1172/JCI71611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitzalis C, Jones GW, Bombardieri M, Jones SA. Ectopic lymphoid-like structures in infection, cancer and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:447–462. doi: 10.1038/nri3700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thaunat O, Kerjaschki D, Nicoletti A. Is defective lymphatic drainage a trigger for lymphoid neogenesis? Trends Immunol. 2006;27:441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drayton DL, Liao S, Mounzer RH, Ruddle NH. Lymphoid organ development: from ontogeny to neogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:344–353. doi: 10.1038/ni1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters A, Pitcher LA, Sullivan JM, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pikor NB, Astarita JL, Summers-Deluca L, et al. Integration of Th17- and lymphotoxin-derived signals initiates meningeal-resident stromal cell remodeling to propagate neuroinflammation. Immunity. 2015;43:1160–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peduto L, Dulauroy S, Lochner M, et al. Inflammation recapitulates the ontogeny of lymphoid stromal cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5789–5799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pikor NB, Prat A, Bar-Or A, Gommerman JL. Meningeal tertiary lymphoid tissues and multiple sclerosis: a gathering place for diverse types of immune cells during CNS autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:657. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazanietz MG, Durando M, Cooke M. CXCL13 and Its receptor CXCR5 in cancer: inflammation, immune response, and beyond. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019;10:471. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Förster R, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Rot A. CCR7 and its ligands: balancing immunity and tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:362–371. doi: 10.1038/nri2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luther SA, Lopez T, Bai W, et al. BLC expression in pancreatic islets causes B cell recruitment and lymphotoxin-dependent lymphoid neogenesis. Immunity. 2000;12:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80199-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y, Chin RK, Christiansen P, et al. Recruitment and activation of naive T cells in the islets by lymphotoxin beta receptor-dependent tertiary lymphoid structure. Immunity. 2006;25:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gräbner R, Lötzer K, Döpping S, et al. Lymphotoxin beta receptor signaling promotes tertiary lymphoid organogenesis in the aorta adventitia of aged ApoE-/- mice. J Exp Med. 2009;206:233–248. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manzo A, Paoletti S, Carulli M, et al. Systematic microanatomical analysis of CXCL13 and CCL21 in situ production and progressive lymphoid organization in rheumatoid synovitis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1347–1359. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barone F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, et al. Association of CXCL13 and CCL21 expression with the progressive organization of lymphoid-like structures in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1773–1784. doi: 10.1002/art.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu-Trantien C, Loi S, Garaud S, et al. CD4+ follicular helper T cell infiltration predicts breast cancer survival. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2873–2892. doi: 10.1172/JCI67428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Couillault C, Germain C, Dubois B, Kaplon H. Identification of tertiary lymphoid structure-associated follicular helper T Cells in human tumors and tissues. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1845:205–222. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8709-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pontarini E, Murray-Brown WJ, Croia C, et al. Unique expansion of IL-21+ Tfh and Tph cells under control of ICOS identifies Sjögren’s syndrome with ectopic germinal centres and MALT lymphoma. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1588–1599. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.GeurtsvanKessel CH, Willart MAM, Bergen IM, et al. Dendritic cells are crucial for maintenance of tertiary lymphoid structures in the lung of influenza virus-infected mice. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2339–2349. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halle S, Dujardin HC, Bakocevic N, et al. Induced bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue serves as a general priming site for T cells and is maintained by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2593–2601. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chiavolini D, Rangel-Moreno J, Berg G, et al. Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) and survival in a vaccine mouse model of tularemia. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sims GP, Shiono H, Willcox N, Stott DI. Somatic hypermutation and selection of B cells in thymic germinal centers responding to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. J Immunol. 2001;167:1935–1944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armengol MP, Juan M, Lucas-Martín A, et al. Thyroid autoimmune disease: demonstration of thyroid antigen-specific B cells and recombination-activating gene expression in chemokine-containing active intrathyroidal germinal centers. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:861–873. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61762-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coronella JA, Spier C, Welch M, et al. Antigen-driven oligoclonal expansion of tumor-infiltrating B cells in infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. J Immunol. 2002;169:1829–1836. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig A, Thaunat O. Lymphoid neogenesis and tertiary lymphoid organs in transplanted organs. Front Immunol. 2016;7:646. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Demoor T, Bracke KR, Maes T, et al. Role of lymphotoxin-alpha in cigarette smoke-induced inflammation and lymphoid neogenesis. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:405–416. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00101408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mohanta SK, Yin C, Peng L, et al. Artery tertiary lymphoid organs contribute to innate and adaptive immune responses in advanced mouse atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2014;114:1772–1787. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleig S, Kapanadze T, Bernier-Latmani J, et al. Loss of vascular endothelial notch signaling promotes spontaneous formation of tertiary lymphoid structures. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2022. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29701-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin C, Mohanta S, Maffia P, Habenicht AJR. Editorial: tertiary lymphoid organs (TLOs): powerhouses of disease immunity. Front Immunol. 2017;8:228. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi GA, Trusov V, et al. Human tuberculous granulomas induce peripheral lymphoid follicle-like structures to orchestrate local host defence in the lung. J Pathol. 2004;204:217–228. doi: 10.1002/path.1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slight SR, Rangel-Moreno J, Gopal R, et al. CXCR5+ T helper cells mediate protective immunity against tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:712–726. doi: 10.1172/JCI65728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kahnert A, Höpken UE, Stein M, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers formation of lymphoid structure in murine lungs. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:46–54. doi: 10.1086/508894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khader SA, Rangel-Moreno J, Fountain JJ, et al. In a murine tuberculosis model, the absence of homeostatic chemokines delays granuloma formation and protective immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:8004–8014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khader SA, Guglani L, Rangel-Moreno J, et al. IL-23 is required for long-term control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and B cell follicle formation in the infected lung. J Immunol. 2011;187:5402–5407. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khader SA, Bell GK, Pearl JE, et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:369–377. doi: 10.1038/ni1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Treerat P, Prince O, Cruz-Lagunas A, et al. Novel role for IL-22 in protection during chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis HN878 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2017;10:1069–1081. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulrichs T, Kosmiadi GA, Jörg S, et al. Differential organization of the local immune response in patients with active cavitary tuberculosis or with nonprogressive tuberculoma. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:89–97. doi: 10.1086/430621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eddens T, Elsegeiny W, de la Garcia-Hernadez M, L,, et al. Pneumocystis-driven inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue formation requires Th2 and Th17 immunity. Cell Rep. 2017;18:3078–3090. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moyron-Quiroz JE, Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, et al. Persistence and responsiveness of immunologic memory in the absence of secondary lymphoid organs. Immunity. 2006;25:643–654. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang X, Chan CCS, Yang M, et al. A critical role of IL-17 in modulating the B-cell response during H5N1 influenza virus infection. Cell Mol Immunol. 2011;8:462–468. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neyt K, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Deswarte K, et al. Early IL-1 signaling promotes iBALT induction after influenza virus infection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:312. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richert LE, Harmsen AL, Rynda-Apple A, et al. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) synergizes with local lymph nodes during antiviral CD4+ T cell responses. Lymphat Res Biol. 2013;11:196–202. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2013.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaushal D, Foreman TW, Gautam US, et al. Mucosal vaccination with attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces strong central memory responses and protects against tuberculosis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8533. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed M, Smith DM, Hamouda T, et al. A novel nanoemulsion vaccine induces mucosal Interleukin-17 responses and confers protection upon Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge in mice. Vaccine. 2017;35:4983–4989. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiley JA, Richert LE, Swain SD, et al. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue elicited by a protein cage nanoparticle enhances protection in mice against diverse respiratory viruses. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kallal LE, Hartigan AJ, Hogaboam CM, et al. Inefficient lymph node sensitization during respiratory viral infection promotes IL-17-mediated lung pathology. J Immunol. 2010;185:4137–4147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bystrom J, Al-Adhoubi N, Al-Bogami M, et al. Th17 lymphocytes in respiratory syncytial virus infection. Viruses. 2013;5:777–791. doi: 10.3390/v5030777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frija-Masson J, Martin C, Regard L, et al. Bacteria-driven peribronchial lymphoid neogenesis in bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;49:1601873. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01873-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hubeau C, Lorenzato M, Couetil JP, et al. Quantitative analysis of inflammatory cells infiltrating the cystic fibrosis airway mucosa. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;124:69–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fleige H, Ravens S, Moschovakis GL, et al. IL-17-induced CXCL12 recruits B cells and induces follicle formation in BALT in the absence of differentiated FDCs. J Exp Med. 2014;211:643–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iwata M, Sato A. Morphological and immunohistochemical studies of the lungs and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue in a rat model of chronic pulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1514–1520. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1514-1520.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kitazawa H, Sato A, Iwata M. A study of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue in a rat model of chronic pulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. 1997;71:214–221. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.71.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Genta RM, Hamner HW, Graham DY. Gastric lymphoid follicles in Helicobacter pylori infection: frequency, distribution, and response to triple therapy. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Genta RM, Lew GM, Graham DY. Changes in the gastric mucosa following eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Mod Pathol. 1993;6:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mazzucchelli L, Blaser A, Kappeler A, et al. BCA-1 is highly expressed in Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and gastric lymphoma. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:R49–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI7830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoneyama H, Matsuno K, Zhang Y, et al. Regulation by chemokines of circulating dendritic cell precursors, and the formation of portal tract-associated lymphoid tissue, in a granulomatous liver disease. J Exp Med. 2001;193:35–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shomer NH, Fox JG, Juedes AE, Ruddle NH. Helicobacter-induced chronic active lymphoid aggregates have characteristics of tertiary lymphoid tissue. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3572–3577. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3572-3577.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freni MA, Artuso D, Gerken G, et al. Focal lymphocytic aggregates in chronic hepatitis C: occurrence, immunohistochemical characterization, and relation to markers of autoimmunity. Hepatology. 1995;22:389–394. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840220203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sansonno D, Tucci FA, Troiani L, et al. Increased serum levels of the chemokine CXCL13 and up-regulation of its gene expression are distinctive features of HCV-related cryoglobulinemia and correlate with active cutaneous vasculitis. Blood. 2008;112:1620–1627. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sansonno D, De Vita S, Iacobelli AR, et al. Clonal analysis of intrahepatic B cells from HCV-infected patients with and without mixed cryoglobulinemia. J Immunol. 1998;160:3594–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pezzolato M, Maina E, Lonardi S, et al. Development of tertiary lymphoid structures in the kidneys of pigs with chronic leptospiral nephritis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012;145:546–550. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steere AC, Duray PH, Butcher EC. Spirochetal antigens and lymphoid cell surface markers in Lyme synovitis. Comparison with rheumatoid synovium and tonsillar lymphoid tissue. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:487–495. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghosh S, Steere AC, Stollar BD, Huber BT. In situ diversification of the antibody repertoire in chronic Lyme arthritis synovium. J Immunol. 2005;174:2860–2869. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Narayan K, Dail D, Li L, et al. The nervous system as ectopic germinal center: CXCL13 and IgG in lyme neuroborreliosis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:813–823. doi: 10.1002/ana.20486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perros F, Dorfmüller P, Montani D, et al. Pulmonary lymphoid neogenesis in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:311–321. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0927OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Colvin KL, Cripe PJ, Ivy DD, et al. Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue in pulmonary hypertension produces pathologic autoantibodies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1126–1136. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0403OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chvatchko Y, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Herren S, et al. Germinal center formation and local immunoglobulin E (IgE) production in the lung after an airway antigenic challenge. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2353–2360. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shinoda K, Hirahara K, Iinuma T, et al. Thy1+IL-7+ lymphatic endothelial cells in iBALT provide a survival niche for memory T-helper cells in allergic airway inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2842–2851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512600113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Litsiou E, Semitekolou M, Galani IE, et al. CXCL13 production in B cells via Toll-like receptor/lymphotoxin receptor signaling is involved in lymphoid neogenesis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:1194–1202. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1543OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solleti SK, Srisuma S, Bhattacharya S, et al. Serpine2 deficiency results in lung lymphocyte accumulation and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue formation. FASEB J. 2016;30:2615–2626. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500159R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Briend E, Ferguson GJ, Mori M, et al. IL-18 associated with lung lymphoid aggregates drives IFNγ production in severe COPD. Respir Res. 2017;18:159. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0641-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lau A, Lester S, Moraitis S, et al. Tertiary lymphoid organs in recalcitrant chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1371–1373.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paramasivan S, Lester S, Lau A, et al. Tertiary lymphoid organs: a novel target in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1673–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Song J, Wang H, Zhang Y-N, et al. Ectopic lymphoid tissues support local immunoglobulin production in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:927–937. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang Z-Z, Song J, Wang H, et al. B Cell-activating factor promotes b cell survival in ectopic lymphoid tissues in nasal polyps. Front Immunol. 2020;11:625630. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.625630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Surawicz CM, Belic L. Rectal biopsy helps to distinguish acute self-limited colitis from idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:104–113. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(84)90595-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kaiserling E. Newly-formed lymph nodes in the submucosa in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Lymphology. 2001;34:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Weninger W, Carlsen HS, Goodarzi M, et al. Naive T cell recruitment to nonlymphoid tissues: a role for endothelium-expressed CC chemokine ligand 21 in autoimmune disease and lymphoid neogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:4638–4648. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carlsen HS, Baekkevold ES, Morton HC, et al. Monocyte-like and mature macrophages produce CXCL13 (B cell-attracting chemokine 1) in inflammatory lesions with lymphoid neogenesis. Blood. 2004;104:3021–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Randolph GJ, Bala S, Rahier J-F, et al. Lymphoid Aggregates remodel lymphatic collecting vessels that serve mesenteric lymph nodes in Crohn disease. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:3066–3073. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Guedj K, Abitbol Y, Cazals-Hatem D, et al. Adipocytes orchestrate the formation of tertiary lymphoid organs in the creeping fat of Crohn’s disease affected mesentery. J Autoimmun. 2019;103:102281. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Houtkamp MA, de Boer OJ, van der Loos CM, et al. Adventitial infiltrates associated with advanced atherosclerotic plaques: structural organization suggests generation of local humoral immune responses. J Pathol. 2001;193:263–269. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH774>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Srikakulapu P, Hu D, Yin C, et al. Artery tertiary lymphoid organs control multilayered territorialized atherosclerosis B-cell responses in aged ApoE-/-Mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:1174–1185. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kyaw T, Tay C, Krishnamurthi S, et al. B1a B lymphocytes are atheroprotective by secreting natural IgM that increases IgM deposits and reduces necrotic cores in atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res. 2011;109:830–840. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.248542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hu D, Mohanta SK, Yin C, et al. Artery tertiary lymphoid organs control aorta immunity and protect against atherosclerosis via vascular smooth muscle cell lymphotoxin β receptors. Immunity. 2015;42:1100–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Humby F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures support ongoing production of class-switched autoantibodies in rheumatoid synovium. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fonseca VR, Romão VC, Agua-Doce A, et al. The ratio of blood T follicular regulatory cells to T follicular helper cells marks ectopic lymphoid structure formation while activated follicular helper T Cells indicate disease activity in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:774–784. doi: 10.1002/art.40424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dorraji SE, Kanapathippillai P, Hovd A-MK, et al. Kidney tertiary lymphoid structures in lupus nephritis develop into large interconnected networks and resemble lymph nodes in gene signature. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:2203–2225. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Korpos É, Kadri N, Loismann S, et al. Identification and characterisation of tertiary lymphoid organs in human type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2021;64:1626–1641. doi: 10.1007/s00125-021-05453-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marinkovic T, Garin A, Yokota Y, et al. Interaction of mature CD3+CD4+ T cells with dendritic cells triggers the development of tertiary lymphoid structures in the thyroid. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2622–2632. doi: 10.1172/JCI28993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Takemura S, Braun A, Crowson C, et al. Lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatoid synovitis. J Immunol. 2001;167:1072–1080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Thurlings RM, Wijbrandts CA, Mebius RE, et al. Synovial lymphoid neogenesis does not define a specific clinical rheumatoid arthritis phenotype. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1582–1589. doi: 10.1002/art.23505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aziz KE, McCluskey PJ, Wakefield D. Characterisation of follicular dendritic cells in labial salivary glands of patients with primary Sjögren syndrome: comparison with tonsillar lymphoid follicles. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:140–143. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, Jonsson R, Brun JG. Serological implications of germinal center-like structures in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2044–2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chang A, Henderson SG, Brandt D, et al. In situ B cell-mediated immune responses and tubulointerstitial inflammation in human lupus nephritis. J Immunol. 2011;186:1849–1860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shen Y, Sun C-Y, Wu F-X, et al. Association of intrarenal B-cell infiltrates with clinical outcome in lupus nephritis: a study of 192 cases. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:967584. doi: 10.1155/2012/967584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.López De Padilla CM, Vallejo AN, Lacomis D, et al. Extranodal lymphoid microstructures in inflamed muscle and disease severity of new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1160–1172. doi: 10.1002/art.24411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Salajegheh M, Pinkus JL, Amato AA, et al. Permissive environment for B-cell maturation in myositis muscle in the absence of B-cell follicles. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:576–583. doi: 10.1002/mus.21739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mohr A, Trésallet C, Monot N, et al. Tissue infiltrating LTi-like group 3 innate lymphoid cells and T follicular helper cells in Graves’ and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:601. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Corsiero E, Jagemann L, Perretti M, et al. Characterization of a synovial B cell-derived recombinant monoclonal antibody targeting stromal calreticulin in the rheumatoid joints. J Immunol. 2018;201:1373–1381. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Corsiero E, Bombardieri M, Carlotti E, et al. Single cell cloning and recombinant monoclonal antibodies generation from RA synovial B cells reveal frequent targeting of citrullinated histones of NETs. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1866–1875. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Corsiero E, Pratesi F, Prediletto E, et al. NETosis as source of autoantigens in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2016;7:485. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Croia C, Astorri E, Murray-Brown W, et al. Implication of Epstein-Barr virus infection in disease-specific autoreactive B cell activation in ectopic lymphoid structures of Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2545–2557. doi: 10.1002/art.38726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Scheel T, Gursche A, Zacher J, et al. V-region gene analysis of locally defined synovial B and plasma cells reveals selected B cell expansion and accumulation of plasma cell clones in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:63–72. doi: 10.1002/art.27767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ekland EH, Forster R, Lipp M, Cyster JG. Requirements for follicular exclusion and competitive elimination of autoantigen-binding B cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:4700–4708. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Le Pottier L, Devauchelle V, Fautrel A, et al. Ectopic germinal centers are rare in Sjogren’s syndrome salivary glands and do not exclude autoreactive B cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:3540–3547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schönbeck S, Padberg F, Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. Transplantation of thymic autoimmune microenvironment to severe combined immunodeficiency mice. A new model of myasthenia gravis. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:245–250. doi: 10.1172/JCI115843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.van de Sande MGH, Thurlings RM, Boumans MJH, et al. Presence of lymphocyte aggregates in the synovium of patients with early arthritis in relationship to diagnosis and outcome: is it a constant feature over time? Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:700–703. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.139287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Klimiuk PA, Goronzy JJ, Björ nsson J, et al. Tissue cytokine patterns distinguish variants of rheumatoid synovitis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:1311–1319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bugatti S, Manzo A, Vitolo B, et al. High expression levels of the B cell chemoattractant CXCL13 in rheumatoid synovium are a marker of severe disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1886–1895. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Xu X, Hsu H-C, Chen J, et al. Increased expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase is associated with anti-CCP and rheumatoid factor in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Immunol. 2009;70:309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2009.02302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lewis MJ, Barnes MR, Blighe K, et al. Molecular portraits of early rheumatoid arthritis identify clinical and treatment response phenotypes. Cell Rep. 2019;28:2455–2470.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Theander E, Vasaitis L, Baecklund E, et al. Lymphoid organisation in labial salivary gland biopsies is a possible predictor for the development of malignant lymphoma in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1363–1368. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Salomonsson S, Jonsson MV, Skarstein K, et al. Cellular basis of ectopic germinal center formation and autoantibody production in the target organ of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3187–3201. doi: 10.1002/art.11311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Risselada AP, Looije MF, Kruize AA, et al. The role of ectopic germinal centers in the immunopathology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;42:368–376. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, Navarro C, et al. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3183–3194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Delli K, Haacke EA, Kroese FGM, et al. Towards personalised treatment in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: baseline parotid histopathology predicts responsiveness to rituximab treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1933–1938. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pijpe J, Meijer JM, Bootsma H, et al. Clinical and histologic evidence of salivary gland restoration supports the efficacy of rituximab treatment in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3251–3256. doi: 10.1002/art.24903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Teng YKO, Levarht EWN, Toes REM, et al. Residual inflammation after rituximab treatment is associated with sustained synovial plasma cell infiltration and enhanced B cell repopulation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1011–1016. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Thurlings RM, Vos K, Wijbrandts CA, et al. Synovial tissue response to rituximab: mechanism of action and identification of biomarkers of response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:917–925. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.080960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]