Summary

Fungal infections affect over a billion people and are responsible for more than 1.5 million deaths each year. Despite progress in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, the management of severe fungal infections remains a challenge. Recently, the reprogramming of cellular metabolism has emerged as a central mechanism through which the effector functions of immune cells are supported to promote antifungal activity. An improved understanding of the immunometabolic signatures that orchestrate antifungal immunity, together with the dissection of the mechanisms that underlie heterogeneity in individual immune responses, may therefore unveil new targets amenable to adjunctive host-directed therapies. In this review, we highlight recent advances in the metabolic regulation of host–fungus interactions and antifungal immune responses, and outline targetable pathways and mechanisms with promising therapeutic potential.

Keywords: immunometabolism, fungal disease, host-directed therapy, antifungal immunity, immunotherapy

An improved understanding of the immunometabolic signatures that orchestrate antifungal immunity is expected to unveil new targets amenable to adjunctive host-directed therapies against fungal infection.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Fungal infections affect over a billion people and are responsible for more than 1.5 million deaths each year [1]. Recent advances in critical care medicine, including solid organ and stem-cell transplantation, chemotherapy, and broad-spectrum antibacterial or immunomodulatory therapy, are contributing to the increasing incidence of severe fungal infections. In developing countries, the immune dysfunction resulting from HIV infection is also associated with susceptibility to fungal disease, while endemic primary fungal pathogens can also cause disease in immunocompetent individuals. In addition, the frequency of life-threatening fungal infections that occur in the context of viral pneumonia, e.g. influenza or COVID-19, is also rapidly expanding [2, 3]. Licensed vaccines are still not available, and despite progress in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, the management of severe fungal infections remains a challenge associated with high mortality rates [4] and healthcare costs [5]. These numbers emphasize the urgent need to further elucidate the pathogenetic mechanisms involved in susceptibility to infection and foster the development of more effective diagnostic and control measures for fungal infections.

In recent years, the identification of several factors and mechanisms related to the immune response has provided exciting developments to our understanding of the pathogenesis of fungal infections [6, 7]. The reprogramming of cellular metabolism has recently emerged as a central mechanism through which the effector functions of immune cells are supported during host antifungal defense [8]. An improved understanding of the immunometabolic signatures that orchestrate antifungal immunity may therefore reveal new targets amenable to adjunctive host-directed therapies, which are currently limited to cytokines, monoclonal antibodies, or cellular immunotherapy [9]. In this review, we discuss recent findings on the immunometabolic signatures activated in response to fungal infection and highlight targetable pathways and mechanisms that show promising potential as adjuncts for host-directed therapies.

Metabolic regulation of the host–fungus interaction

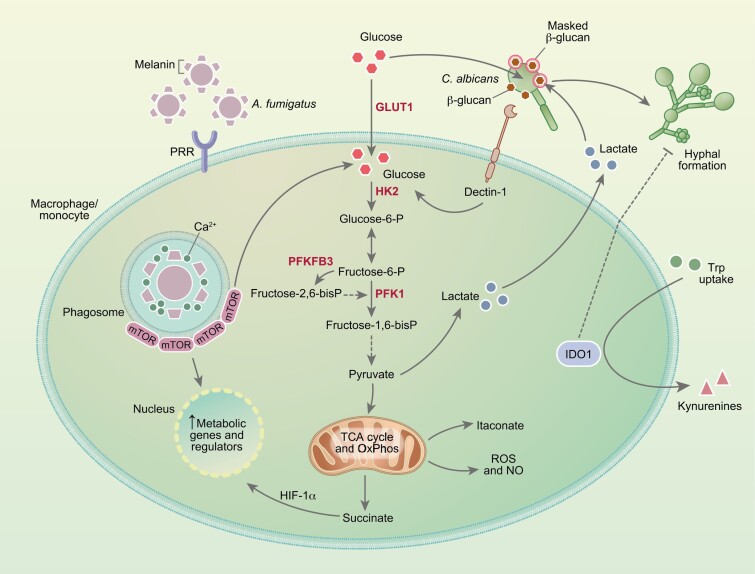

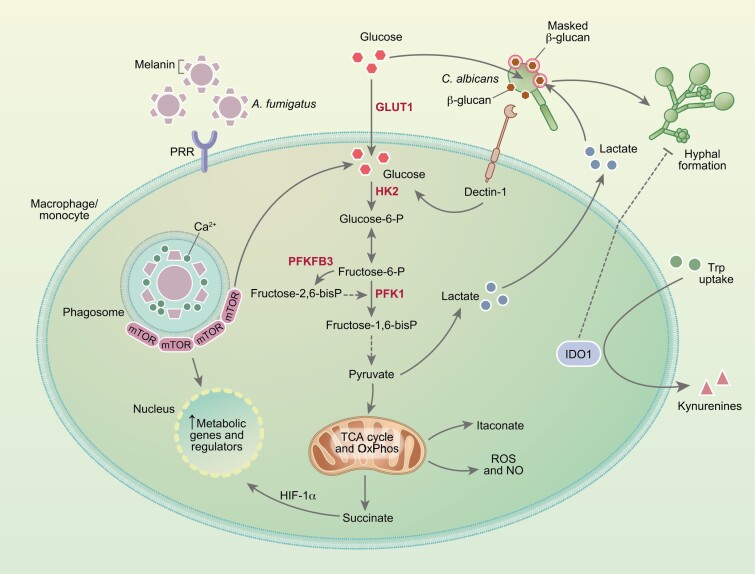

Metabolism is a determining factor of immune cell function [10]. Upon infection, immune cells sense molecular patterns from pathogens and remodel their metabolic outputs beyond their normal energy requirements (Fig. 1). Different metabolites are used as signaling molecules, enzymatic cofactors, and substrates that support the activation of immune effector functions, including phagocytosis, cytokine production, cell surface receptor expression, antigen presentation, and the control of long-term responses. In turn, pathogens can sense the metabolites produced by activated immune cells and reshape their ligand repertoire to hide from or subvert the immune response [11]. These observations highlight the profound impact of coordinated metabolic networks on the outcome of the host–pathogen interaction.

Fig. 1.

Metabolic reprogramming of myeloid cells in response to fungal infection. Recognition of fungal pathogens by pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) is accompanied by the upregulation of glycolysis and production of lactate. In these conditions, the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) are often repressed, resulting in the accumulation of intermediates such as succinate and itaconate, and enhancing the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. In response to C. albicans, the activation of glycolysis is triggered by the recognition of β-glucan by dectin-1, a process that can be in turn exploited by the fungus through its ability to compete for glucose and ultimately promote macrophage death. Sensing of lactate secreted by immune cells also drives the masking of β-glucans in the fungal cell wall and immune evasion. The activation of glycolysis during infection with A. fumigatus is instead triggered by the release of melanin during germination. By sequestering calcium within the phagosome, melanin promotes the recruitment of mTOR which, in turn, mediates the activation of downstream metabolic genes and regulators. The catabolism of tryptophan (Trp) by the indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) enzyme also regulates antifungal immune responses and controls fungal morphology through its downstream catabolites, collectively referred to as kynurenines (Kyn).

Glucose metabolism of immune cells is at the center of antifungal immune responses, potentiating the production of proinflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory mediators, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8]. In the context of fungal infections, this metabolic route in immune cells has been predominantly studied in response to Candida albicans [12–16] but has also recently been shown to occur during infection with Aspergillus fumigatus [17] and Cryptococcus gattii [18]. Although glycolysis is often induced in a context of reduced oxidative phosphorylation, leading to the so-called Warburg effect [16], human monocytes challenged with C. albicans are nonetheless endowed with functional oxidative phosphorylation [13]. This implies that immunometabolic signatures vary in intensity and nature according to the microbial insult or the receptor involved [19]. Likewise, the metabolic remodeling in response to infection with C. albicans also depends on the fungal morphotype [13]. While monocytes stimulated with the yeast form rely on glycolysis and glutaminolysis to mount cytokine responses, hyphal stimulation primarily drives the activation of glycolysis. These divergent profiles are likely due to the variable expression of the β-glucan polysaccharide in the yeast and hyphal cell wall. In this regard, β-glucan masking was shown to be induced by lactate-mediated signals that control the expression of cell wall-related genes [20]. Moreover, by taking advantage of its efficient metabolic fitness, C. albicans exploits the terminal commitment of macrophages to glycolysis by competing for and depleting available glucose, ultimately leading to rapid cell death [16]. These findings depict crucial virulence traits from fungi that, by exploiting or subverting host metabolism, contribute to evasion from the immune system (Fig. 1).

In contrast to C. albicans, the expression of β-glucan in the cell wall of A. fumigatus appears instead to be largely dispensable to the activation of glycolysis in macrophages [17]. Instead, the phagosomal release of melanin from the surface of conidia was shown to regulate calcium-dependent signals leading to enhanced glycolysis through the activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) (Fig. 1). These findings are in line with the requirement for HIF-1α to the modulation of cytokine release by human dendritic cells upon infection with A. fumigatus [21] and the non-redundant role of HIF-1α in mouse models of aspergillosis [22]. Of note, the metabolic reprogramming induced by fungal melanin appears to occur regardless of its recently identified receptor MelLec [23]. Instead, the germination process associated with the active removal of melanin within the phagosome is required for host cells to rewire their metabolism. In support of this, germination has been shown to promote fungal clearance, as faster-growing CEA10-derived strains are cleared more efficiently in vivo than slower-growing Af293-derived strains [24]. This enhanced fungal elimination could thus be explained by cell wall rearrangements culminating with melanin release during germination and the activation of host glycolysis. Whatever the mechanism(s), the efficient regulation of glycolysis is required for resistance to aspergillosis in humans. This is illustrated by the recent finding that genetic variation in 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), a critical regulator of glucose metabolism, was found to impair antifungal effector functions of macrophages and predispose recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation to the development of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis [25]. PFKFB3 is upregulated in bacterial infections and PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in macrophages is critical for antiviral defense [26], pinpointing this gene as a possible therapeutic target across infectious diseases. Moreover, the similar regulation of glycolysis in immune cells in response to different infectious agents [27] highlights the attractive possibility of exploiting genetic variants in metabolic genes and their effects on immunometabolic signatures as a tool to identify and stratify the patients most at risk of infectious diseases.

Immunoregulatory functions of host metabolites in fungal infection

The metabolic switch to glycolysis results in the accumulation of several intermediates of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle that act as signals to link metabolism and immunity. In recent years, the metabolite itaconate has been explored for its broad immunomodulatory properties. Activated myeloid cells display enhanced expression of the immune-responsive gene 1 (IRG1) mitochondrial enzyme, which catalyzes the decarboxylation of the TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate to itaconate [28]. The molecular mechanisms under control by itaconate vary, but the net function is thought to be anti-inflammatory. Itaconate inhibits the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), which is both an enzyme of the TCA cycle and the complex II of the electron transport chain, leading to succinate accumulation and impaired mitochondrial respiration, and suppressing the production of inflammatory cytokines [29]. Moreover, itaconate enables the activation of the transcription factors NRF2 and ATF3, and the increased expression of downstream genes with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, and the modulation of type I interferon responses [30].

Itaconate plays an important role across several infections, decreasing tissue injury in a mouse model of tuberculosis [31] and enhancing the bactericidal activity of macrophage-lineage cells in zebrafish [32]. During infection with the Zika virus, itaconate was found to alter the neuronal metabolism to suppress viral replication [33], indicating that its modulatory effects are not restricted to myeloid cells. The direct antimicrobial functions of itaconate are thought to rely largely on the inhibition of isocitrate lyase, an enzyme of the glyoxylate shunt that is essential for growth under glucose-poor conditions, and that is required for the virulence of several pathogens, including C. albicans [31, 34, 35]. In contrast, bacteria often harbor genes involved in itaconate degradation, allowing them to counter the inhibitory mechanisms deployed by itaconate and survive inside the host [36]. Moreover, pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were recently shown to adapt to itaconate-rich environments and use this metabolite as a carbon source for the production of biofilms, contributing to the establishment and progression of infection [37, 38]. The therapeutic administration of inhaled itaconate has been shown to improve pulmonary fibrosis in mice [39], a disease that often develops due to exposure to airborne fungi [40] and that, in turn, further potentiates the development of respiratory fungal infections [41]. Whether itaconate plays a role in the immune response to fungal pathogens other than C. albicans remains to be explored, although the metabolism of acetate, a carbon source metabolized also through the glyoxylate shunt, impacts virulence traits and the pathogenicity of A. fumigatus [42].

In response to inflammatory stimuli, macrophages accumulate succinate that, in turn, acts as a proinflammatory redox signal to the transcription factor HIF-1α and the production of IL-1β [43]. Succinate oxidation also potentiates the generation of mitochondrial ROS [44], which represent critical effectors required for antifungal immunity [45]. Indeed, the balance between the production of ROS and reactive nitrogen species by the host and the fungal stress response is a key feature of the host–fungus interaction [46]. The production of nitric oxide (NO) is modulated by the metabolism of amino acids, which also plays an important role in macrophage polarization [47]. In this regard, C. albicans was shown to upregulate arginase activity and limit NO production in macrophages via chitin-mediated signals, skewing macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory profile which ultimately restrains antimicrobial functions and mediates fungal survival [48]. In contrast, granulocyte-mediated clearance of A. fumigatus occurred independently of arginine availability [49], a finding that supports distinct pathogen-driven metabolic strategies to subvert antifungal immune responses.

The catabolism of tryptophan via the activity of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) also represents an essential mechanism in the modulation of antifungal immunity [50]. IDO1 acts as a physiological checkpoint that controls immune homeostasis through its downstream catabolites – referred to as kynurenines – and provides the host with adequate protective immune mechanisms [51]. In particular, IDO1 activity induces differentiation of T regulatory cells, while inhibiting the development of T helper 17 cells, thus playing a central role in cell lineage commitment across experimental fungal infections in the context of detrimental inflammation, including chronic granulomatous disease and cystic fibrosis [52, 53]. The airway expression of IDO1 was also found to inhibit pathogenic T cells in response to fungal antigens [54], a finding consistent with the requirement for IDO1 activity in the non-hematopoietic cell compartment for protective tolerance against A. fumigatus [55]. Tryptophan-derived metabolites may also be produced through the activity of bacterial communities in the intestinal microbiota, which establishes a highly tolerant immunological microenvironment allowing the commensalism of C. albicans in the gut [56]. Of note, IDO1 activity was found to be required to inhibit the yeast-to-hyphae transition of C. albicans [57].

The expression and function of IDO1 are influenced by common human genetic variation [58]. Accordingly, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in IDO1 that impair its expression were found to influence the risk of developing recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis [59], as well as aspergillosis in patients with cystic fibrosis and recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation [60]. Remarkably, A. fumigatus was recently found to harbor genes encoding fungal IDO1-like enzymes and their deletion resulted in increased virulence in a mouse model of aspergillosis [61], thus highlighting the crucial role of the interplay between fungal and host tryptophan metabolic routes in shaping host-fungus interactions. Collectively, the bulk of available data suggests that drugs capable of potentiating IDO1 expression and activity may represent valuable therapeutic tools and that IDO1-based immunotherapeutics could be more effective if tailored to the genetic profile of individual patients [62].

Trained immunity as a therapeutic strategy to rescue immune impairments

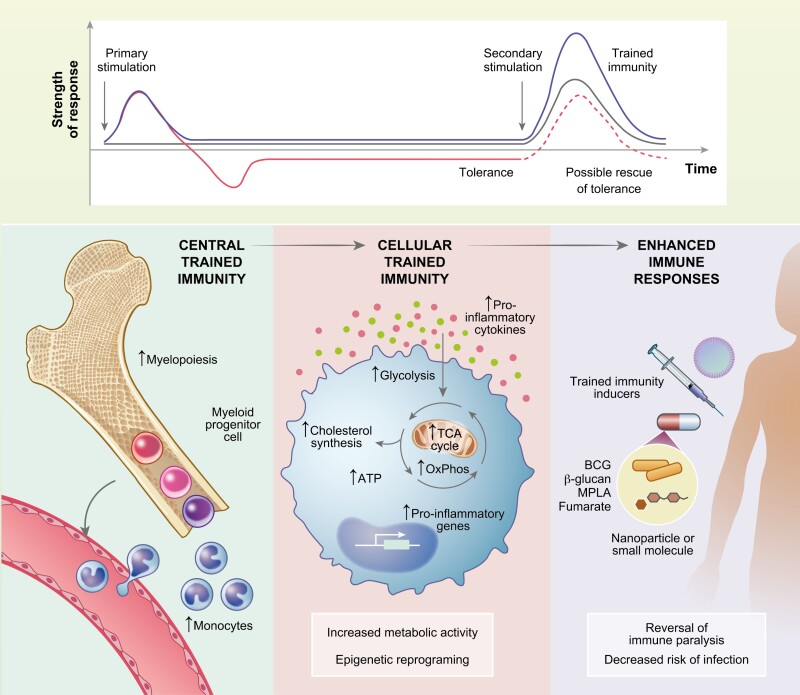

A growing body of evidence has revealed alterations of the innate immune system that potentiate responses and ultimately generate characteristics of memory [63]. Trained immunity, a de facto innate immune memory, allows for a long-lasting and broad-spectrum resistance to pathogens. In this context, macrophage exposure to the vaccine Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), fungal β-glucan, or oxidized low-density lipoprotein enhanced effector functions toward subsequent heterologous stimuli, while it conferred protection against secondary lethal infections in mouse models, namely by C. albicans [15,64,65].

Trained cells harbor altered metabolic programs that sustain the rewiring of the epigenetic landscape and allow for enhanced immune effector functions. Trained macrophages rely on a highly energetic metabolism characterized by enhanced glycolysis, TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation [64]. In accordance, the mTOR/HIF-1α axis was demonstrated to mediate the metabolic and functional reprogramming of β-glucan-trained macrophages [12]. Cholesterol biosynthesis is also a central pathway for trained immunity as shown by its induction by the intermediate mevalonate [66]. Trained immunity is also conferred by the epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming of hematopoietic stem cells and their skewing toward myelopoiesis [67, 68]. The broad clinical relevance of this molecular process was emphasized in a recent randomized clinical trial that showed that BCG vaccination of elderly individuals decreased the incidence of new respiratory infections [69]. The induction of trained immunity thus represents an interesting tool to harness the potential of innate immunity in patients with immune impairments (Fig. 2). However, increasing immune responses may be particularly challenging in selected pathologies. Not only can immune cells be epigenetically encoded to dampen responses to inflammatory stimuli, but also the decreased number of circulating immune cells might not be sufficient even if their activity is potentiated.

Fig. 2.

Trained immunity as a tool to potentiate host defense. Microbial or endogenous stimuli activate innate immune cells. Depending on the dose or stimuli, innate immune function may be increased when encountering a secondary stimulation (trained immunity) or cells may become unresponsive or anti-inflammatory (tolerance). Trained immunity confers long-term protection thought the myelopoietic skewing of hematopoietic stem cells, giving rise to monocytes with enhanced effector functions. They rely on metabolic changes, such as increased glycolysis and OxPhos, which supports epigenetic rewiring that promotes the expression of proinflammatory genes culminating in the increased secretion of cytokines. Thus, trained immunity inducers may be an attractive therapeutic tool to revert tolerance, possibly rescuing states of immune paralysis in sepsis and decreasing the risk of secondary infections.

In patients under intensive care, fungal infections often give rise to sepsis, which involves the hyperactivation of the immune system followed by tolerance or immune paralysis. Immune paralysis also comprehends epigenetic and metabolic changes [70] but, in contrast to trained immunity programs, these changes ultimately increase the susceptibility to secondary infections [71, 72]. Exposure to β-glucan restored the responsive phenotype of human monocytes tolerized with LPS, a finding that was confirmed in a human endotoxemia model [73]. The integrity of the TCA cycle in LPS-stimulated macrophages was maintained by β-glucan through the inhibition of IRG1 expression [74]. Of note, while the anti-inflammatory properties of itaconate make it an interesting target for the reversal of immune paralysis, at the same time, itaconate may also represent a valuable therapeutic tool to decrease detrimental and exacerbated antifungal immune responses.

Another functional feature of patients with sepsis regards the defective activation of LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), a non-canonical autophagy pathway that plays a non-redundant role in the resistance to infection with A. fumigatus [75–77]. Recently, monocytes from patients with sepsis were found to display a defective activation of LAP, which was reversed by the administration of recombinant IL-6 [78]. It is thus tempting to consider the modulation of LAP as a promising immunotherapeutic intervention in sepsis, particularly given the ability of β-glucan to increase the expression of Rubicon [79], a critical effector molecule of LAP. The induction of trained immunity could thus also represent a promising avenue for the treatment of fungal sepsis.

Several trained immunity inducers are already under clinical use. For example, muramyl tripeptide is employed in the treatment of osteosarcoma and BCG is in clinical use for bladder cancer [80]. Notably, trained immunity was found to be elicited by dimethyl fumarate [81], a drug currently under use for the management of multiple sclerosis [82]. Also approved for human use is the vaccine adjuvant and TLR4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid A (MPLA). MPLA has been shown to not only improve resistance to several pathogens, including C. albicans [83] but also to induce the metabolic rewiring of macrophages characterized by a sustained increase in glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation [83] in a similar manner to other inducers of trained immunity. Collectively, these molecules represent attractive candidates for repurposing toward the induction of trained immunity in immunocompromised patients.

Targeting metabolic homeostasis at the host–fungus interface

During infection, the host and the pathogen compete for limiting levels of nutrients, such as glucose. It is thus not surprising that a glucose-rich diet has been found to improve the survival of mice in a model of disseminated candidiasis [16]. Importantly, induction of trained immunity may also prevent macrophage death due to glucose starvation. Trained macrophages not only present increased glycolysis but also display increased oxidative phosphorylation, and thus trained cells might not be committed to glycolysis for energy production. A benefit of the enhanced glucose uptake is also envisaged in uremic individuals, who exhibit a hyperinflammatory state and are at increased risk of developing fungal infections. Uremia downregulates the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway, causing hyperactivation of the glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and thus inhibiting glucose uptake [84]. Accordingly, the pharmacological blockade of GSK3β using the specific inhibitor SB415286 or lithium chloride restored glucose uptake, but also ROS production and the candidacidal activity of neutrophils, in a mouse model of kidney disease with systemic fungal infection. The preclinical efficacy of GSK3β inhibition was confirmed by the rescue of the fungal killing capacity in neutrophils isolated from hemodialysis patients. Nutritional supplementation was also protective against influenza infection and viral sepsis, but it was instead detrimental in bacterial sepsis by Listeria monocytogenes [85]. Therefore, although favoring glucose metabolism may represent a promising therapeutic possibility, the opposing effects of fasting metabolism on different infections suggest its utility on a pathogen-dependent basis.

Exacerbated immune responses to infection may also drive fungal sepsis. In this scenario, it might be advantageous to combine antifungal agents with inhibitors of glucose uptake and glycolysis to ultimately decrease inflammation. In this regard, the glucose analog 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) that blocks glucose metabolism was found to decrease cytokine production in mouse models of infection with C. albicans [13] and A. fumigatus [17]. Moreover, metformin, a widely used drug in the treatment of type 2 diabetes as a glucose-lowering agent, which activates the AMP kinase and inhibits mTOR, or the mTOR blockade itself, decreased cytokine production and survival in experimental disseminated candidiasis [13, 16]. Other inhibitors of glucose uptake or glycolysis, such as the HIV-protease inhibitor ritonavir [86], the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitor dichloroacetate [87], and the small-molecule competitive lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor FX11 [88] might also be of future interest in the context of fungal infections.

The rewiring of metabolic pathways may consume or compartmentalize metabolites, restricting pathogen access to nutrients, as depicted for glucose accessibility during infection. Interestingly, the pulmonary niche was found to impose a decreased responsiveness of alveolar macrophages, by impairing glycolysis and promoting pathways of lipid metabolism [89]. These findings highlight the crucial role of the tissue milieu for both immune responses and the virulence of pathogens, including fungi. Moreover, the metabolic profiles differ at different tissues, providing substrates that regulate not only fungal fitness, but also immune cell function and their interaction. Another example of compartmentalization derives from anemia of inflammation, which arises due to infections or autoimmune disorders that promote a proinflammatory state [90]. Host and invading pathogens compete for iron availability, as it is an essential co-factor for several proteins relevant for a myriad of processes, such as DNA replication and mitochondrial function. Iron is especially relevant for highly proliferative cells, and lack of iron blunts T- and B-cell responses [91]. Systemic immune activation of the host induces changes in iron intestinal absorption, trafficking, and cellular retention, thus decreasing iron availability to pathogens. To counter this, fungi produce siderophores that capture iron from host iron-binding proteins in human serum, while restricting iron access to host immune cells and modulating their activity [92]. Accordingly, elevated circulating iron levels have been associated with an increased risk of systemic fungal infection in hematological patients [93]. Moreover, the iron chelator deferiprone was shown to decrease fungal burden in a mouse model of cornea infection by A. fumigatus [94] and improve survival of mice infected with the mucormycete Rhizopus oryzae [95]. Ciclopirox, a potent topical antifungal agent, exerts its effects partly by chelating polyvalent metal cations such as iron [96]. Inhibition of fungal iron uptake, namely via targeted iron chelation therapies, represents thus an interesting therapeutic strategy.

Iron is not only a limiting nutrient for pathogen virulence [97, 98], but it also plays a regulatory role in host immune responses [99]. For example, iron-loaded macrophages exhibited a proinflammatory phenotype in diverse disease contexts, such as spinal cord injury [100], multiple sclerosis [101], and cancer [102]. On the other hand, acute iron chelation promotes an anti-inflammatory shift, as seen by the decrease in LPS-induced cytokine production by human macrophages [103]. This acute iron deprivation also enhanced glycolysis and lipid droplet formation while it downregulated oxidative phosphorylation, possibly due to the disruption of the iron-containing complex II of the respiratory chain. Interestingly, labile heme induces a trained immunity program that confers protection against LPS-induced sepsis in mice [104]. Thus, the targeted modulation of iron accessibility, be it by iron chelation when a proinflammatory phenotype is maladaptive, or by the delivery of iron in nanoparticles or heme to promote inflammation [105] is an attractive avenue to tailor immune metabolism and function.

Concluding remarks

The goal of host-direct approaches targeting immunometa-bolism is ultimately the exploitation of intrinsic metabolic pathways in the treatment of disease, including fungal infections. The targeting of host metabolism instead of fungal traits would decrease selective pressure and consequently diminish the development of unwanted resistance to antifungals. Selected metabolic pathways may be harnessed to potentiate immune responses or dampen them when they become maladaptive, while considering the pathogen involved, the affected tissue, and the disease state. Importantly, a rational strategy to identify and interpret immunometabolic signatures of susceptibility to fungal infection through the immune profiling by multi-omics approaches, including genomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, holds the promise to identify patients at high risk of infection that would benefit the most from targeted preventative measures. To achieve this goal, further studies are needed to better understand the pathogenesis of fungal diseases, their progression profile in time and space, and the host–fungus interplay in the context of effector immune cells. The exploitation of new approaches to study the diverse metabolic programs of specific cells, tissues, and diseased states is ultimately necessary to pave the way toward the effective clinical modulation of immunometabolism in the field of fungal disease.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 2-DG

2-deoxy-D-glucose

- AMP

Adenosine monophosphate

- ATF3

Activating transcription factor 3

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- GSK3β

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IDO1

Indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1

- IL

Interleukin

- IRG1

Immune-responsive gene 1

- LAP

LC3-associated phagocytosis

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MPLA

Monophosphoryl lipid A

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NO

Nitric oxide

- NRF2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- PFKFB3

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SDH

Succinate dehydrogenase

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

Contributor Information

Samuel M Gonçalves, Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), School of Medicine, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Guimarães/Braga, Portugal.

Anaísa V Ferreira, Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), School of Medicine, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Guimarães/Braga, Portugal; Department of Internal Medicine and Radboud Center for Infectious Diseases (RCI), Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar (ICBAS), Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal.

Cristina Cunha, Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), School of Medicine, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Guimarães/Braga, Portugal.

Agostinho Carvalho, Life and Health Sciences Research Institute (ICVS), School of Medicine, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Guimarães/Braga, Portugal.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) (PTDC/SAU-SER/29635/2017, PTDC/MED-GEN/28778/2017, UIDB/50026/2020, and UIDP/50026/2020), the Northern Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020), under the Portugal 2020 Partnership Agreement, through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000039), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 847507, and the “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) and FCT under the agreement LCF/PR/HR17/52190003. Individual support was provided by FCT (SFRH/BD/136814/2018 to S.M.G., PD/BD/135449/2017 to A.V.F., and CEECIND/04058/2018 to C.C.).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author contributions

Conception: S.M.G., A.V.F., C.C., and A.C. Preparation of figures: S.M.G. and A.V.F. Writing and literature review: S.M.G. and A.V.F. Critical revision of the article: C.C. and A.C. All authors have read, edited, and approved the final version of the article.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- 1. Bongomin F, Gago S, Oladele RO, Denning DW.. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J Fungi (Basel) 2017, 3, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verweij PE, Rijnders BJA, Brüggemann RJM, et al. Review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and proposal for a case definition: an expert opinion. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 1524–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arastehfar A, Carvalho A, van de Veerdonk FL, et al. COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA)-from immunology to treatment. J Fungi (Basel) 2020, 6, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA, et al. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 760–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benedict K, Jackson BR, Chiller T, Beer KD.. Estimation of direct healthcare costs of fungal diseases in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2019, 68, 1791–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Netea MG, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ, van de Veerdonk FL.. Immune defence against Candida fungal infections. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 630–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van de Veerdonk FL, Gresnigt MS, Romani L, Netea MG, Latge JP.. Aspergillus fumigatus morphology and dynamic host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2017, 15, 661–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weerasinghe H, Traven A.. Immunometabolism in fungal infections: the need to eat to compete. Curr Opin Microbiol 2020, 58, 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams TJ, Harvey S, Armstrong-James D.. Immunotherapeutic approaches for fungal infections. Curr Opin Microbiol 2020, 58, 130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Neill LA, Pearce EJ.. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J Exp Med 2016, 213, 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Traven A, Naderer T.. Central metabolic interactions of immune cells and microbes: prospects for defeating infections. EMBO Rep 2019, 20, e47995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 2014, 345, 1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Domínguez-Andrés J, Arts RJW, Ter Horst R, et al. Rewiring monocyte glucose metabolism via C-type lectin signaling protects against disseminated candidiasis. PLoS Pathog 2017, 13, e1006632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hellwig D, Voigt J, Bouzani M, et al. Candida albicans induces metabolic reprogramming in human NK cells and responds to perforin with a zinc depletion response. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JHA, et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 12, 223–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tucey TM, Verma J, Harrison PF, et al. Glucose homeostasis is important for immune cell viability during candida challenge and host survival of systemic fungal infection. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 988–1006.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonçalves SM, Duarte-Oliveira C, Campos CF, et al. Phagosomal removal of fungal melanin reprograms macrophage metabolism to promote antifungal immunity. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rosa RL, Berger M, Santi L, et al. Proteomics of rat lungs infected by Cryptococcus gattii reveals a potential warburg-like effect. J Proteome Res 2019, 18, 3885–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lachmandas E, Boutens L, Ratter JM, et al. Microbial stimulation of different Toll-like receptor signalling pathways induces diverse metabolic programmes in human monocytes. Nat Microbiol 2016, 2, 16246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ballou ER, Avelar GM, Childers DS, et al. Lactate signalling regulates fungal β-glucan masking and immune evasion. Nat Microbiol 2016, 2, 16238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fliesser M, Morton CO, Bonin M, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha modulates metabolic activity and cytokine release in anti-Aspergillus fumigatus immune responses initiated by human dendritic cells. Int J Med Microbiol 2015, 305, 865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shepardson KM, Jhingran A, Caffrey A, et al. Myeloid derived hypoxia inducible factor 1-alpha is required for protection against pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus infection. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10, e1004378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stappers MHT, Clark AE, Aimanianda V, et al. Recognition of DHN-melanin by a C-type lectin receptor is required for immunity to Aspergillus. Nature 2018, 555, 382–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosowski EE, Raffa N, Knox BP, Golenberg N, Keller NP, Huttenlocher A.. Macrophages inhibit Aspergillus fumigatus germination and neutrophil-mediated fungal killing. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gonçalves SM, Antunes D, Leite L, et al. Genetic variation in PFKFB3 impairs antifungal immunometabolic responses and predisposes to invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. mBio 2021, 12, e0036921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiang H, Shi H, Sun M, et al. PFKFB3-driven macrophage glycolytic metabolism is a crucial component of innate antiviral defense. J Immunol 2016, 197, 2880–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ayres JS. Immunometabolism of infections. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O’Neill LAJ, Artyomov MN.. Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lampropoulou V, Sergushichev A, Bambouskova M, et al. Itaconate links inhibition of succinate dehydrogenase with macrophage metabolic remodeling and regulation of inflammation. Cell Metab 2016, 24, 158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mills EL, Ryan DG, Prag HA, et al. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 2018, 556, 113–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nair S, Huynh JP, Lampropoulou V, et al. Irg1 expression in myeloid cells prevents immunopathology during M. tuberculosis infection. J Exp Med 2018, 215, 1035–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall CJ, Boyle RH, Astin JW, et al. Immunoresponsive gene 1 augments bactericidal activity of macrophage-lineage cells by regulating β-oxidation-dependent mitochondrial ROS production. Cell Metab 2013, 18, 265–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Daniels BP, Kofman SB, Smith JR, et al. The nucleotide sensor ZBP1 and kinase RIPK3 induce the enzyme IRG1 to promote an antiviral metabolic state in neurons. Immunity 2019, 50, 64–76.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen M, Sun H, Boot M, et al. Itaconate is an effector of a Rab GTPase cell-autonomous host defense pathway against Salmonella. Science 2020, 369, 450–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lorenz MC, Fink GR.. The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 2001, 412, 83–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sasikaran J, Ziemski M, Zadora PK, Fleig A, Berg IA.. Bacterial itaconate degradation promotes pathogenicity. Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tomlinson KL, Lung TWF, Dach F, et al. Staphylococcus aureus induces an itaconate-dominated immunometabolic response that drives biofilm formation. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Riquelme SA, Liimatta K, Wong Fok Lung T, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa utilizes host-derived itaconate to redirect its metabolism to promote biofilm formation. Cell Metab 2020, 31, 1091–106.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ogger PP, Albers GJ, Hewitt RJ, et al. Itaconate controls the severity of pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Immunol 2020, 5, eabc1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fukuda Y, Homma T, Suzuki S, et al. High burden of Aspergillus fumigatus infection among chronic respiratory diseases. Chron Respir Dis 2018, 15, 279–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar N, Mishra M, Singhal A, Kaur J, Tripathi V.. Aspergilloma coexisting with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a rare occurrence. J Postgrad Med 2013, 59, 145–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ries LNA, Alves de Castro P, Pereira Silva L, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus acetate utilization impacts virulence traits and pathogenicity. mBio 2021, 12, e0168221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature 2013, 496, 238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mills EL, Kelly B, Logan A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase supports metabolic repurposing of mitochondria to drive inflammatory macrophages. Cell 2016, 167, 457–70.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hatinguais R, Pradhan A, Brown GD, Brown AJP, Warris A, Shekhova E.. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate immune responses of macrophages to Aspergillus fumigatus. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 641495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warris A, Ballou ER.. Oxidative responses and fungal infection biology. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2019, 89, 34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kieler M, Hofmann M, Schabbauer G.. More than just protein building blocks: how amino acids and related metabolic pathways fuel macrophage polarization. FEBS J 2021, 288, 3694–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wagener J, MacCallum DM, Brown GD, Gow NA.. Candida albicans chitin increases arginase-1 activity in human macrophages, with an impact on macrophage antimicrobial functions. mBio 2017, 8, e01820–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kapp K, Prüfer S, Michel CS, et al. Granulocyte functions are independent of arginine availability. J Leukoc Biol 2014, 96, 1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Carvalho A, Cunha C, Bozza S, et al. Immunity and tolerance to fungi in hematopoietic transplantation: principles and perspectives. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Proietti E, Rossini S, Grohmann U, Mondanelli G.. Polyamines and kynurenines at the intersection of immune modulation. Trends Immunol 2020, 41, 1037–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Iannitti RG, Carvalho A, Cunha C, et al. Th17/Treg imbalance in murine cystic fibrosis is linked to indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase deficiency but corrected by kynurenines. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 187, 609–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Romani L, Fallarino F, De Luca A, et al. Defective tryptophan catabolism underlies inflammation in mouse chronic granulomatous disease. Nature 2008, 451, 211–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paveglio SA, Allard J, Foster Hodgkins SR, et al. Airway epithelial indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibits CD4+ T cells during Aspergillus fumigatus antigen exposure. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2011, 44, 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Luca A, Bozza S, Zelante T, et al. Non-hematopoietic cells contribute to protective tolerance to Aspergillus fumigatus via a TRIF pathway converging on IDO. Cell Mol Immunol 2010, 7, 459–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zelante T, Iannitti RG, Cunha C, et al. Tryptophan catabolites from microbiota engage aryl hydrocarbon receptor and balance mucosal reactivity via interleukin-22. Immunity 2013, 39, 372–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bozza S, Fallarino F, Pitzurra L, et al. A crucial role for tryptophan catabolism at the host/Candida albicans interface. J Immunol 2005, 174, 2910–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Orabona C, Mondanelli G, Pallotta MT, et al. Deficiency of immunoregulatory indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1in juvenile diabetes. JCI insight 2018, 3, e96244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. De Luca A, Carvalho A, Cunha C, et al. IL-22 and IDO1 affect immunity and tolerance to murine and human vaginal candidiasis. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Napolioni V, Pariano M, Borghi M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms affecting IDO1 or IDO2 activity differently associate with aspergillosis in humans. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zelante T, Choera T, Beauvais A, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus tryptophan metabolic route differently affects host immunity. Cell Rep 2021, 34, 108673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mondanelli G, Iacono A, Carvalho A, et al. Amino acid metabolism as drug target in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 2019, 18, 334–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ferreira AV, Domiguez-Andres J, Netea MG.. The role of cell metabolism in innate immune memory. J Innate Immun 2022, 14, 42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Arts RJW, Carvalho A, La Rocca C, et al. Immunometabolic pathways in BCG-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep 2016, 17, 2562–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Riksen NP.. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 34, 1731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bekkering S, Arts RJW, Novakovic B, et al. Metabolic induction of trained immunity through the mevalonate pathway. Cell 2018, 172, 135–46.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kaufmann E, Sanz J, Dunn JL, et al. BCG educates hematopoietic stem cells to generate protective innate immunity against tuberculosis. Cell 2018, 172, 176–90.e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mitroulis I, Ruppova K, Wang B, et al. Modulation of myelopoiesis progenitors is an integral component of trained immunity. Cell 2018, 172, 147–61.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Tsilika M, Moorlag S, et al. Activate: randomized clinical trial of BCG vaccination against infection in the elderly. Cell 2020, 183, 315–23.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cheng SC, Scicluna BP, Arts RJ, et al. Broad defects in the energy metabolism of leukocytes underlie immunoparalysis in sepsis. Nat Immunol 2016, 17, 406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP.. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science 2012, 335, 936–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shalova IN, Lim JY, Chittezhath M, et al. Human monocytes undergo functional re-programming during sepsis mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Immunity 2015, 42, 484–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Novakovic B, Habibi E, Wang SY, et al. β-Glucan reverses the epigenetic state of LPS-induced immunological tolerance. Cell 2016, 167, 1354–68.e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dominguez-Andres J, Novakovic B, Li Y, et al. The itaconate pathway is a central regulatory node linking innate immune tolerance and trained immunity. Cell Metabolism 2019, 29, 211–20 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kyrmizi I, Ferreira H, Carvalho A, et al. Calcium sequestration by fungal melanin inhibits calcium-calmodulin signalling to prevent LC3-associated phagocytosis. Nat Microbiol 2018, 3, 791–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kyrmizi I, Gresnigt MS, Akoumianaki T, et al. Corticosteroids block autophagy protein recruitment in Aspergillus fumigatus phagosomes via targeting dectin-1/Syk kinase signaling. J Immunol 2013, 191, 1287–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Martinez J, Malireddi RK, Lu Q, et al. Molecular characterization of LC3-associated phagocytosis reveals distinct roles for Rubicon, NOX2 and autophagy proteins. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 893–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 78. Akoumianaki T, Vaporidi K, Diamantaki E, et al. Uncoupling of IL-6 signaling and LC3-associated phagocytosis drives immunoparalysis during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1277–93.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sun Z, Qu J, Xia X, et al. 17β-Estradiol promotes LC3B-associated phagocytosis in trained immunity of female mice against sepsis. Int J Biol Sci 2021, 17, 460–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Mourits VP, Wijkmans JC, Joosten LA, Netea MG.. Trained immunity as a novel therapeutic strategy. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2018, 41, 52–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, et al. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab 2016, 24, 807–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Carlström KE, Ewing E, Granqvist M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of dimethyl fumarate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis associates with ROS pathway in monocytes. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fensterheim BA, Young JD, Luan L, et al. The TLR4 agonist monophosphoryl lipid A drives broad resistance to infection via dynamic reprogramming of macrophage metabolism. J Immunol 2018, 200, 3777–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Jawale CV, Ramani K, Li DD, et al. Restoring glucose uptake rescues neutrophil dysfunction and protects against systemic fungal infection in mouse models of kidney disease. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12, eaay5691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Wang A, Huen SC, Luan HH, et al. Opposing effects of fasting metabolism on tissue tolerance in bacterial and viral inflammation. Cell 2016, 166, 1512–25.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Noor MA, Flint OP, Maa JF, Parker RA.. Effects of atazanavir/ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir on glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity: demonstrable differences in vitro and clinically. AIDS 2006, 20, 1813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. James MO, Jahn SC, Zhong G, Smeltz MG, Hu Z, Stacpoole PW.. Therapeutic applications of dichloroacetate and the role of glutathione transferase zeta-1. Pharmacol Ther 2017, 170, 166–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Krishnamoorthy G, Kaiser P, Abu Abed U, et al. FX11 limits Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth and potentiates bactericidal activity of isoniazid through host-directed activity. Dis Models Mech 2020, 13, dmm041954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Svedberg FR, Brown SL, Krauss MZ, et al. The lung environment controls alveolar macrophage metabolism and responsiveness in type 2 inflammation. Nat Immunol 2019, 20, 571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weiss G, Ganz T, Goodnough LT.. Anemia of inflammation. Blood 2019, 133, 40–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Frost JN, Tan TK, Abbas M, et al. Hepcidin-mediated hypoferremia disrupts immune responses to vaccination and infection. Med (N Y) 2021, 2, 164–79.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hissen AH, Chow JM, Pinto LJ, Moore MM.. Survival of Aspergillus fumigatus in serum involves removal of iron from transferrin: the role of siderophores. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 1402–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Iglesias-Osma C, Gonzalez-Villaron L, San Miguel JF, Caballero MD, Vazquez L, de Castro S.. Iron metabolism and fungal infections in patients with haematological malignancies. J Clin Pathol 1995, 48, 223–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Leal SM Jr, Roy S, Vareechon C, et al. Targeting iron acquisition blocks infection with the fungal pathogens Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium oxysporum. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Andrianaki AM, Kyrmizi I, Thanopoulou K, et al. Iron restriction inside macrophages regulates pulmonary host defense against Rhizopus species. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Subissi A, Monti D, Togni G, Mailland F.. Ciclopirox: recent nonclinical and clinical data relevant to its use as a topical antimycotic agent. Drugs 2010, 70, 2133–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Almeida RS, Brunke S, Albrecht A, et al. the hyphal-associated adhesin and invasin Als3 of Candida albicans mediates iron acquisition from host ferritin. PLoS Pathog 2008, 4, e1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Potrykus J, Stead D, Maccallum DM, et al. Fungal iron availability during deep seated candidiasis is defined by a complex interplay involving systemic and local events. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ludwiczek S, Aigner E, Theurl I, Weiss G.. Cytokine-mediated regulation of iron transport in human monocytic cells. Blood 2003, 101, 4148–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kroner A, Greenhalgh AD, Zarruk JG, Passos Dos Santos R, Gaestel M, David S.. TNF and increased intracellular iron alter macrophage polarization to a detrimental M1 phenotype in the injured spinal cord. Neuron 2014, 83, 1098–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gillen KM, Mubarak M, Nguyen TD, Pitt D.. Significance and in vivo detection of iron-laden microglia in white matter multiple sclerosis lesions. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Costa da Silva M, Breckwoldt MO, Vinchi F, et al. Iron induces anti-tumor activity in tumor-associated macrophages. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Pereira M, Chen TD, Buang N, et al. Acute iron deprivation reprograms human macrophage metabolism and reduces inflammation in vivo. Cell Rep 2019, 28, 498–511.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Jentho E, Novakovic B, Ruiz-Moreno C, et al. Heme induces innate immune memory. bioRxiv 2019, 2019:12.12.874578. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zanganeh S, Hutter G, Spitler R, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles inhibit tumour growth by inducing pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization in tumour tissues. Nat Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 986–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.