Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has strongly impacted our society, producing drastic changes in people’s routines and daily mobility, and putting public spaces under a new light. This paper starts with the premise that the use of urban forests and green spaces - where and for who they were available and accessible - increased, when social restrictions were most stringent. It takes an explorative approach to examine changes in attitude towards urban forests and urban green spaces in terms of attraction (i.e., as the actual use behaviour), intended use (i.e., intention of going to green spaces), and civic engagement in relation to green spaces. In particular, it analyses the responses to a survey of 1987 respondents in Belgium and statistically examines the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, urbanisation characteristics, actual and intended green space use, and changes in attitudes towards green spaces and civic engagement. The findings show that highly educated citizens experienced an increase in actual and intended use of green spaces during the pandemic, but that this increase differs among sociodemographic profiles such as impact of age or access to private green, and depends on their local built environment characteristics. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic has strongly impacted citizens’ attitudes, as well as (intended) behaviour and civil engagement with respect to the green spaces in their area.

Keywords: Attitude changes, Civic engagement, Coronavirus pandemic, Green space

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is having significant impacts on society. In particular, a combination of governmental restrictions on social behaviour and concerns about infection has resulted in a drastic change in the way people use urban green spaces (UGS). Being part of the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy of the EU (European Commission (EC), 2020), UGS contribute to both mitigation and adaptation of climate change, support biodiversity conservation, and are key for ensuring and maintaining physical and mental health and human wellbeing (van den Bosch and Sang, 2017; Rall et al., 2017). Providing a full range of ecosystem services (Haase et al., 2014), these areas are places of recreation, encounter or physical activity, provide heat and noise mitigation and air filtration, and promote social networking and inclusion (Kaplan and Kaplan, 2011; European Commission (EC), 2013; Wei, 2017). The 2030 EU Biodiversity Strategy (European Commission (EC), 2020) foresees a larger role for urban green spaces and urban forestry to restore biodiversity and strengthen physical and mental well-being supporting a green recovery after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2020 and 2021 economic and societal lockdowns have been associated with physical and mental health risks to those confined to their homes or home offices. In this situation of confinement, the importance of spending time in UGS has become more apparent than ever and contact with UGS is expected to have a bigger role in individual’s mental and physical health than before the pandemic. Where available and accessible, UGS have been (re)discovered during the COVID-19 pandemic, with increased use for both physical exercise, stress reduction and mental calming (European Commission (EC), 2020; Grima et al., 2020; Natural England, 2020; Ugolini et al., 2020). Among others, Google Maps data showed an impressive increase of mobility to places like national parks, public beaches, marinas, dog parks, plazas, and public gardens, amidst a general fall in mobility trends (see Geng et al., 2021). For New York, for instance, Lopez et al. (2020) showed that respondents considered urban green spaces more important for mental and physical health during the pandemic. Similarly, the study of Grima et al. (2020) showed that residents of Vermont (USA) greatly increased their visitation rate to natural areas and urban forests, but also perceived importance of these areas become greater than before. These areas were identified as important both because of wide range of activities that they provide, but also because of their value to reduce stress in a time of global chaos. Maintaining good health and wellbeing are the main reasons why people spend more time in nature such as gardens, parks, or woodlands than before the pandemic (Natural England, 2020). In some countries – including Belgium – governmental policies encouraged people to spend as much time outdoors as possible, while still respecting social distancing guidelines and travel restrictions (Gray and Kellas, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic and the policy counter measures, however, have also produced either uneven or even unjust accessibility options to UGS for certain sociodemographic groups. It has been well-documented in literature that access to UGS is unevenly distributed, particularly in urban areas, and thus increases social and environmental injustice (Haase, 2020; Honey-Roses et al., 2020; Simon, 2020). Vulnerable groups tend to have less access to green spaces, public or private (Honey-Roses et al., 2020) and are disproportionately affected by the impacts of COVID-19 (Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020). Additionally, research shows that highly educated individuals and households generally followed a healthier lifestyle, including regular green space use, compared to the average population (Kabisch et al., 2016a, 2016b). With the pandemic restrictions, these households are able to make more frequent use of the home office option and could access private or public UGS more easily. In contrast, lower income households were fixed at their workplaces, since residents with lesser educational attainment more often work in jobs that cannot shift to home office easily (e.g., essential caring jobs and retail distribution). For instance, a study by Natural England (2020) reports that one third of respondents did not visit a natural space in a two-week period. These responses were associated with the respondents’ socioeconomic status: people who live alone or in an area of high deprivation, with a low income or a low level of education, or are not working, are less likely to have visited UGS (Ibid.). Moreover, groups who are most susceptible to poor mental health include elderly people, children, ethnic minorities, those with a long-term illness or condition, and those without children (McNeil et al., 2020; Brooks et al., 2020). Of course, besides limited opportunities of using UGS, an individual’s sense of safety of contracting or spreading the coronavirus, anti-social behaviour, and the lack of facilities further influence the frequency of visiting UGS (Natural England, 2020; Lopez et al., 2020).

Besides these socioeconomic differences, there are spatial differences in the way residents have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and responded to restrictions due to different forms of mobility, social network and interactions, and preventive behaviour between urban and rural areas. Honey-Roses et al. (2020) question what spatial and temporal changes in the use of public spaces (incl. urban green spaces) might be observed as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic. They hypothesise that practices of planning public spaces based on pedestrian counting and modelling may undergo a major upheaval following the pandemic. Similar changes are expected in the temporal patterns and spacing of users over the day, as people try to avoid peak hours.

Against this background, this explorative paper questions to what extent increased use of UGS during the pandemic goes along with sociodemographic and spatial differences. In particular, it examines the impact of the place of residence on the (intended) green space use and changes in attitude. This research explores the results from a survey of 1987 respondents in Belgium, distributed during the pandemic's first wave. It statistically examines the relationship between socio-demographics (gender, age, care giving responsibilities), (intended) green space use and changes in attitudes towards green spaces in terms of attraction (i.e., as the actual use behaviour), and civic engagement with UGS. The paper is structured as follows. A contextual narrative on the relationship between green space use and personal characteristics provides a background to the case study context during the 2020 spring lockdown. This is followed by an explanation of the applied methodology and a description of the main findings of the research. Finally, in the conclusion and discussion section, we evaluate these findings with respect to the context and research questions and highlight possible follow-ups to the research.

2. Literature review and context

2.1. Attitudes towards green spaces: a review of the literature

This section illustrates the state of the academic literature on the attitudes of urban residents towards urban green spaces (UGS) in Europe and their use of these spaces, as well as how attitudes and use are connected to residents’ sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age), living environment (whether they live in urban or periurban areas), and access to public or private UGS.

The health benefits experienced by and the well-being of people who visit UGS are widely acknowledged (Vujičić et al., 2019; Douglas et al., 2017; Tomao et al., 2016; World Health Organization (WHO), 2016; Carrus et al., 2015; Davies et al., 2015; Pietilä et al., 2015; Tamosiunas et al., 2014). The positive health and well-being effects of green space over a lifespan (in the prenatal period and in all age-groups) have been identified in many studies (Douglas et al., 2017). The frequency of visits and length of stay in UGS may have an effect on visitors’ perceived well-being. For instance, a representative study conducted in Italy and the UK showed that the higher the frequency and duration of UGS visits, the greater the benefits and well-being reported by respondents (Lafortezza et al., 2009). The scientific literature acknowledges the importance for urban residents of having accessible and well-maintained green areas (especially public) that provide spaces for a variety of activities (Giannico et al., 2021; Fischer et al., 2018; Krajter Ostoić et al., 2017; Kabisch et al., 2016a, 2016b; Jurkovic, 2014). However, in the case of lack of access to public green space, access to private green space may compensate for health and well-being benefits (e.g., Tu et al., 2016). Recent research shows that this need for accessible and safe green space was especially emphasised during the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular during the lockdown (Ugolini et al., 2021, 2020; Derks et al., 2020). The same is valid for accessible private green space (Poortinga et al., 2021).

Actual use of UGS, personal motivations for visiting UGS and visiting behaviour (time of visit, with whom, how visitors reach their destination, duration of stay, what they do there) may be related to many variables. For instance, a representative national Danish survey investigated factors influencing the use of UGS (Schipperijn et al., 2010a). Almost half of respondents visited UGS daily and more than 90 % at least once a week. The most important reasons were to enjoy the weather and fresh air, to reduce stress/to relax, and to exercise. Gender, age, education, marital status and ethnic background were all significantly associated with UGS use in this study. Indeed, studies show that especially gender and age are important predictors of UGS use and people’s visiting behaviour (Mertens et al., 2019; Fischer et al., 2018; Ode Sang et al., 2016; Schipperijn et al., 2010b). In some studies female visitors tend to be more involved in passive activities (Mertens et al., 2019), but this is not a rule (Ode Sang et al., 2016). Even a movement of visitors through local UGS may depend on age and gender, as a recent Swedish study has shown (Ode Sang et al., 2020). In this study the movement pattern differed significantly between men and women as well as between young adults and old adults. In a study on park use in several European cities, physical activity was the most frequently reported use of UGS, especially taking a walk (Fischer et al., 2018). The study also emphasised the importance of sociocultural and geographic contexts for park use. Perceived distance to UGS may also be the main reason for visiting or not visiting certain UGS in a sense that longer perceived distance is the reason for infrequent visits (Žlender and Ward Thompson, 2017). Peri-urban green spaces in this study were appreciated by urban residents for similar reasons. Respondents expressed preference for semi-natural features in comparison to formal parks and playing fields. Convenience of access and frequency of visits are strongly connected to green space planning policies (green wedges strategy in Ljubljana vs. green belt strategy in Edinburgh).

Availability of accessible UGS may influence the place where people choose to live (Czembrowski and Kronenberg, 2016; Tu et al., 2016). This means that people may opt to pay more for their home if it is in a greener neighbourhood. However, this choice is a result of many other factors, while accessibility of green space is only one of these factors. People in lower-density neighbourhoods were found to experience their living environment more positively than those in higher-density neighbourhoods (Jurkovic, 2014). However, the compact city policy that is common across Western countries may conflict with people’s desire to live in lower-density neighbourhoods with private gardens, as a Dutch study shows (Coolen and Meesters, 2012). The same study shows that public and private green spaces are both meaningful but different settings and not simple substitutes for each other. On the contrary, a French choice experiment study conducted in Nancy showed that ownership of a private garden may reduce the willingness to pay to live closer to an urban park, indicating that substituting one with the other may work in some cases (Tu et al., 2016).

Urban residents may become involved in green space governance initiatives with a variety of objectives in mind, and these initiatives may play a major role in planning, protecting or managing green space (Mattijssen et al., 2018). The analysis of trends and practices in participatory governance across the European Union based on 20 case studies in 14 countries shows that participatory governance practice varies (van der Jagt et al., 2017). Local governments in some cities in Northern and Western Europe may have a range of policy tools and instruments to enable participatory governance (involve people), while this is not the case in cities in Southeast Europe.

2.2. The Belgian context during the 2020 spring lockdown

This paper focuses on the Belgian context. Belgium is a densely populated country, with 374 inhabitants per km² on average, reaching up to 7501 inhabitants per km² in the Brussels Capital Region (Statistics Belgium, 2020). Not only is the population density high, but the historic lack of a long-term spatial planning has resulted in a large spread of the population outside of concentrated town centres, in what could be described as one big suburb, sometimes referred to as “nevelstad” (fog city or dispersed city) (Bruggeman, 2016; Poelmans and Van Rompaey, 2009).

Belgium has a relatively low forest cover index (22 %), ranging between 2.3 % in the province of West-Flanders to over 50 % in the southern province of Luxembourg. Moreover, 55 % of the forests are privately owned, and while some are accessible to the public, a large share is not. High population density is correlated with heavy forest use (cf. Roovers et al., 2002; Hunziker et al., 2020), meaning that the few publicly accessible forests can get overcrowded. The need for more public UGS, especially in urban environments, is clear, and in recent years many towns and cities have been working on the creation of accessible urban or peri-urban forests (Van Herzele, 2015). In contrast to (peri-)urban nature reserves, which have long since been established and mainly aim for biodiversity targets, these forest parks primarily have a recreational function, as do inner city parks and playgrounds.

In March 2020, the federal government of Belgium announced a state of “lockdown” to curb the spread of the virus. Similar to many European countries, the measures that were taken drastically impacted citizens’ mobility and routines. The main restrictions that directly or indirectly affected people’s leisure time during the first lockdown are summed up in Table 1 . A more detailed and extensive description of the main lockdown restrictions is available in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Main restrictions during the Spring 2020 lockdown in Belgium.

|

The grey shade shows the period when the survey was distributed.

Importantly, two of the few activities that were continuously allowed were regional walks and bicycle rides, which led to large crowds (re)discovering the area where people live. This is in contrast to neighbouring countries like France, for instance, where people could venture no more than one kilometre from their home, or Germany, where people were still allowed to use the car for non-essential transportation purposes. The logical consequence was that - especially in urban areas - the pressure on UGS rose. This effect was exacerbated by the fact that some local authorities decided to close specific public UGS out of fear of mass gatherings, as well as by the fact that playgrounds were closed. Combined with a general increase in forest use during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, this led to a significantly increased pressure on (urban) forests in Belgium and beyond (cf. Derks et al., 2020).

3. Methods and data

3.1. European-wide survey on UGS use and civic engagement

This research was conducted in the context of the CLEARING HOUSE project, an international project bringing together researchers and practitioners in Europe and China to provide evidence and tools that facilitate the mobilisation of the full potential relating to UGS including parks and forest areas for rehabilitating, reconnecting and restoring urban ecosystems. We developed an online survey to understand the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on people’s use and relationship to UGS. The survey consisted of six main sections. In section one, respondents were asked to provide information on their place of residence and their access to UGS. Section two asked respondents to compare their use of UGS before and during the lockdown. Respondents were asked how often they visited UGS and for what reason(s), whether there were barriers preventing them from using UGS, and whether they think UGS should be a service that is prioritised by their local government. For each question, respondents were asked to indicate what their answer would have been before the lockdown and how they answered at the time of the survey during the lockdown. In section three, we further delved into the changes in UGS use during the lockdown. In this section, respondents were asked whether and how their frequency of UGS use had changed, why they visited UGS during the lockdown, and, if applicable, why they visited UGS less or more frequently during the lockdown. Section four asked respondents to reflect on their intended change in attitude and behaviour in the long run after the lockdown. Respondents were asked how often they intend to use UGS once restrictions are lifted (in relation to how often they used UGS before the lockdown), whether their attitude towards UGS will change, and whether they feel their local government should prioritise UGS once restrictions have been lifted. In section five, respondents provided basic background information, such as gender, age, educational qualifications, employment status, whether they had caretaking responsibilities during lockdown, and if so, how their employment situation had changed during lockdown. Finally, in section six, respondents were given the opportunity to provide additional thoughts in an open-ended question.

3.2. Data collection logit models

The survey was distributed in Spring 2020 (available between April 25 and July 10) in 10 European countries when the pandemic was reaching its first peak and severe social restrictions were adopted in many countries. It was available in multiple languages (English, French, Dutch, German, Italian, Polish and Finnish). The survey was shared via mailing lists, social media, traditional media and snowball sampling via the network of the researchers. Appendix B presents the English version of the survey.

Because most of the respondents were based in Belgium, we decided to focus on Belgium for this paper. However, the distribution strategy implied a degree of self-selection bias, which resulted in focusing the research only around the questions for which the sample was deemed appropriate. In addition, the digital nature of the survey excluded possible respondents with limited access to internet (e.g., the digital divide). We acknowledge that this methodology leads to a sampling bias. However, involving the most vulnerable population groups (i.e., lower income households or elderly) during lockdown times is extraordinarily complex and the limited contact opportunities has resulted in this primarily virtual way of contacting respondents. Although a clear limitation, it does exhibit innovative results at least for the sample group and provides insights in ways to study other groups.

3.3. Survey analysis

The collected survey data were statistically analysed through descriptive statistics and regression analysis to identify the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown impacted respondents’ use and attitudes towards UGS. First, descriptive statistics were used to analyse stated change in UGS frequency of use (before versus) during the pandemic, and whether respondents perceived a shift in their prioritisation of UGS as a service provided by local governments. Additionally, we identified how respondents intended to change their behaviour following the pandemic in terms of civic engagement and intention to move to a greener neighbourhood or to a home with private green.

We then applied ordinal and binary logistic regression analyses to explore whether foreseen changes in attitude toward UGS, use of UGS, and prioritisation of UGS as a service were linked to certain independent variables. The independent variables studied include sociodemographic characteristics (gender and age), caregiving responsibilities during the lockdown, characteristics of respondents’ built environment (urban, peri-urban, rural), and respondents’ access to private and public UGS. Characteristics of the built environment were based on an urban gradient analysis at the municipality level for Belgium conducted by Vanderstraeten and Van Hecke (2019), using information on population movements in terms of residence, work and school commute; income; and employment and regional development. Table 2 outlines the independent variables included in the research, as well as the corresponding survey question, possible responses, and coding of these responses for the regression analysis.

Table 2.

Independent variables included in the research, and corresponding survey question, possible responses, and coding of the responses for the regression analysis.

| Survey question | Survey response | Coding | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Q6.2 Gender | Male | 0 |

| Female | 1 | ||

| Age | Q6.3 Age | Less than 18 years old | 0 |

| 18 to 29 | 1 | ||

| 30 to 39 | 2 | ||

| 40 to 49 | 3 | ||

| 50 to 59 | 4 | ||

| 60 to 69 | 5 | ||

| 70 to 79 | 6 | ||

| More than 80 | 7 | ||

| Care responsibilities | Q6.6 – Did you have care giving responsibilities during the COVID quarantine (e.g. young children, elderly, people with disabilities…)? | No | 0 |

| Yes/Yes, shared | 1 | ||

| Urbanisation | Q2.4 What is your zip code? | Rural | 0 |

| Urban | 1 | ||

| Access to private green | Q2.5 What green spaces are normally available to you? | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 | ||

| Access to public green within 500 m from respondent’s residence | Q2.5 What green spaces are normally available to you? | No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify significant independent variables related to intended changes in frequency of UGS use and foreseen changes in prioritisation of UGS. Responses to questions 5.1 (“How often will you visit green spaces after the coronavirus restrictions are lifted?) and 5.3 (“Do you consider green spaces and urban forests a service that your local government should prioritize after the quarantine restrictions are lifted?”) were included in this analysis. Possible responses to these questions were presented as five-point Likert scales from “considerably less than before the quarantine” to considerably more than before the quarantine” for question 5.1 and “very low priority” to “very high priority” for question 5.3. Goodness of fit for the ordinal logistic regression models was tested with a Lipsitz test (Lipsitz et al., 1996).

Next, binary logistic regression was used to identify significant variables related to foreseen changes in attitude, including whether respondents planned to join a movement, ask for action from the local government, move to a greener neighbourhood, or move to a house with access to private green This was based on responses to question 5.2, “Will there be any changes in your attitude toward green spaces?”. Binary logistic regression is used here because we consider each possible response to the question as a dependent variable. For example, we test whether the aforementioned independent variables (e.g. gender, age, care responsibilities) correspond with a singular intended change in behaviour/attitude (e.g. “I intend to move to a new residence with a private green space”). In this case, (1) indicates that particular response to question 5.2 was selected by respondents, while (0) indicates that it was not. As we are only interested in intended changes in attitude, we do not include the response “I do not foresee any change” in our analysis. Goodness of fit for the binary logistic regression models was tested with a Hosmer-Lemeshow test (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2013).

In the following section, we present the results of the ordinal and binary logistic regressions. The results, presented in tables, include the regression coefficient, standard error (SE), p-value, and the odds ratio (OR). The regression coefficient indicates the log odds change of each outcome for a one-unit increase in the predictor variable. The standard error indicates the uncertainty of the coefficients. The p-value tells us whether the relationship is statistically significant, and the odds ratio tells us about the strength of the observed relationships.

4. Results

4.1. Description of survey respondents

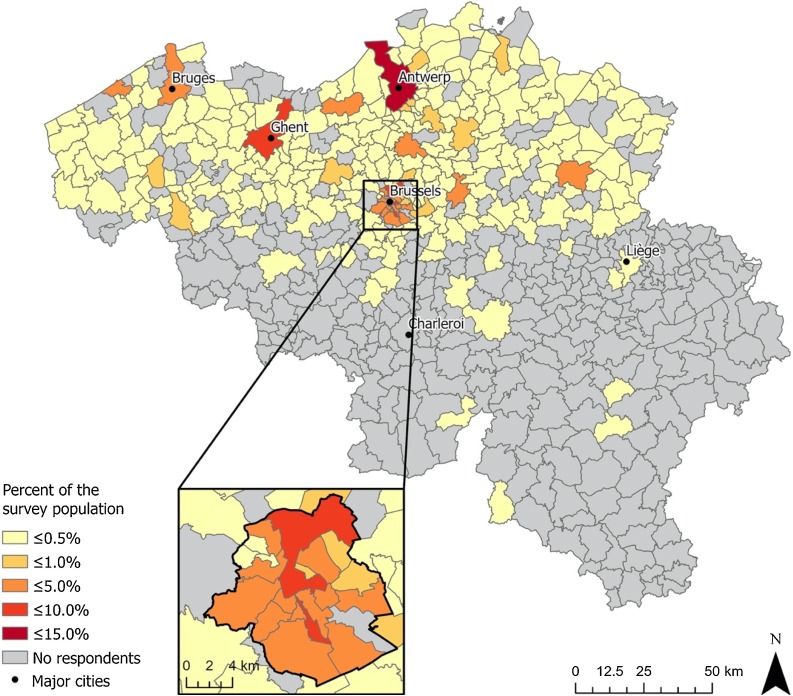

Following the processing of the survey response data for Belgium, there were 2042 complete responses and 321 partial responses. Of the total 2363 responses, 1987 were considered valid. Table 3 shows that this subset of the sample includes 1178 female (59.28 %), 787 male (39.60 %) and 24 respondents that answered ‘other’ or ‘prefer not to say’ (1.11 %). In terms of age, we received responses from all age groups, although the sample was skewed towards people between 30 and 49 years of age (48.36 %). Looking at education and occupation, there was a significant overrepresentation of respondents with university diploma or higher (85.91 % versus 32.86 % for the Belgian population, Statistics Belgium, 2020) and employed respondents (77.80 % versus 70.20 % in the global Belgian population between 20 and 64 years, Statistics Belgium, 2020). A varied picture emerged in terms of work-related changes due to the pandemic (52.11 % started to mainly work from home, 32.33 % of the respondents’ situation did not change and 8.23 % stopped working because of the pandemic). While the sample may not reflect the sociodemographic composition of all regions where the survey was distributed, we did receive a significant number of answers from a series of subgroups (e.g., retired people, 13.89 %, or people with a secondary school diploma only, 12.33 %). Respondents were largely concentrated in the northern Flemish region (n = 1359) of Belgium and in the Brussels Capital Region (n = 583), whereas the number of respondents in the southern Walloon region was limited (Fig. 1 ).

Table 3.

Comparison of the survey population distribution with respect to the Belgian population. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Survey Population (%) | Belgium (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 39.60 | 49.25 |

| Female | 59.29 | 50.75 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 18 years old | 0.10 | 20.12 |

| Between 18 and 29 | 15.25 | 14.49 |

| Between 30 and 39 | 26.93 | 12.98 |

| Between 40 and 49 | 21.44 | 13.09 |

| Between 50 and 59 | 17.56 | 13.84 |

| Between 60 and 69 | 15.40 | 11.72 |

| Between 70 and 79 | 3.12 | 8.04 |

| More than 80 | 0.20 | 5.71 |

| Educational qualification | ||

| Primary education or no diploma | 0.65 | 11.34 |

| Secondary education | 12.33 | 55.80 |

| University graduate or similar | 71.97 | 16.15 |

| Post-university graduate | 13.94 | 16.71 |

| Other | 1.11 | – |

| Employment | ||

| Employed (public/private, freelance) | 77.80 | 69.6 |

| Unemployed | 2.68 | 2.9 |

| Resident's built environment | ||

| Core agglomeration | 36 % | 30 % |

| Rest of agglomeration | 21 % | 15 % |

| Suburbs | 22 % | 11 % |

| Commuting residential zone | 11 % | 19 % |

| Outside of urban living complexes | 10 % | 25 % |

Fig. 1.

Percentage of survey respondents per municipality (n = 1987). Responses are concentrated in Flanders, particularly around major cities.

4.2. Changes in stated UGS use and stated attitude towards UGS

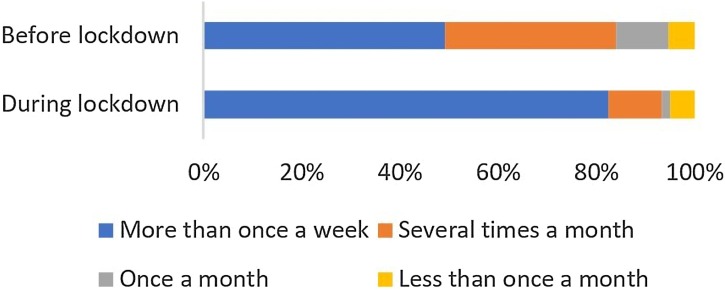

Fig. 2 shows that most respondents more frequently used UGS during the lockdown. Prior to the lockdown, 49 % of respondents visited a UGS more than once a week. During the lockdown, over 80 % of respondents indicated to use a UGS more than once a week. Of these 80 %, 35 % previously indicated using UGS several times a month, 8% indicated using UGS once a month, and 4% indicated using UGS less than once a month.

Fig. 2.

Responses to the question “How often did you visit green spaces?”. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of use before and during the lockdown (n = 1987).

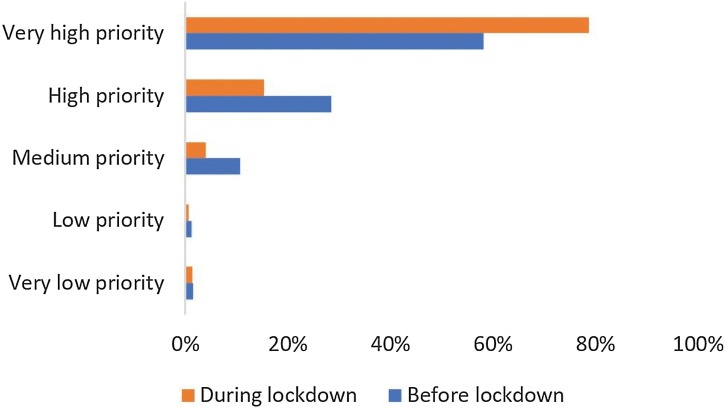

When asked to reflect on whether they feel the local government should have prioritised UGS before the lockdown, the majority of respondents (58 %) indicated that they felt local government should give UGS “very high” priority (Fig. 3 ). This increased during the lockdown, with a large majority of respondents indicating that local governments should give UGS “very high” priority (79 %). Most of the change in priority to “very high” occurred for those already giving “medium” (4%) or “high” (22 %) priority to UGS before the lockdown.

Fig. 3.

Responses to the question “Do you consider green spaces and urban forests a service that your local government should prioritise?”. Respondents were asked to rank their prioritisation of UGS before and during the lockdown (n = 1987).

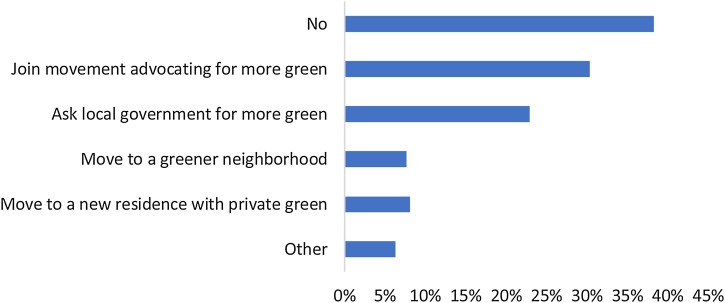

Fig. 4. Responses to the question “Will there be any changes in your attitude towards green spaces?” (n = 1987). Illustrates that 38 % of respondents indicated not to foresee any changes in their civic engagement or their living situation following the lockdown. However, 30 % indicated that they intend to join a movement to advocate for more UGS and 23 % will ask their local government for more UGS. Fewer respondents indicated that they intend to move to a greener neighbourhood (8%) or to a residence with more private green (8%). Four percentage of the respondents indicated that they want to move to a greener neighbourhood as well as intend to move to a residence with more private green.

Fig. 4.

Responses to the question “Will there be any changes in your attitude towards green spaces?” (n = 1987).

4.3. Changes in use and attitude in relation to variables related to sociodemographics and living environment

Ordinal logistic regression was used to identify the relationship between several independent variables and intended changes in frequency of UGS use following the lockdown. This analysis showed that gender, age, access to public green and caregiving responsibilities were identified as significant variables (Table 4 , p-value 0.364). The results show that women as well as respondents with caregiving responsibilities are more likely to anticipate that they will increase their UGS visiting (with a factor of 0.198 and 0.462 respectively). In addition, as age increases, the likelihood of intent to increase UGS use decreases by a factor of 0.451. If a respondent has access to public green, the likelihood of an intended increase in UGS use increases by a factor of 0.502.

Table 4.

Ordinal logistic regression analysis based on the question “How often will you visit green spaces after the coronavirus restrictions are lifted?” Respondents rated their intended frequency on a 5-point Likert scale from “considerably less than before the quarantine” to “considerably more than before the quarantine”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | 0.181 | 0.085 | 0.033** | 1.198 |

| Age | −0.599 | 0.102 | 0.000*** | 0.549 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | 0.380 | 0.194 | 0.051* | 1.462 |

| No | 0.178 | 0.188 | 0.345 | 1.194 |

| Urbanisation | −0.041 | 0.106 | 0.701 | 0.960 |

| Access to private green | −0.149 | 0.095 | 0.117 | 0.861 |

| Access to public green | 0.407 | 0.114 | 0.000*** | 1.502 |

LR statistics (Lipsitz) = 9.8314, df = 9, p-value 0.364 | AIC: 5371.831.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

Respondents were asked the degree to which they feel their local government should prioritise UGS and urban forests as a service. Age and urbanisation level of the place of residence were found to significantly correspond to intent to change prioritisation of UGS as a service provided by local governments (Table 5 , p-value 0.018). An increase in age corresponds with a decrease in prioritisation by a factor of 0.242. Respondents with access to a private green space prioritised UGS less than those without private green by a factor of 0.221. However, a low p-value for the model indicates a relatively poor model fit (Lipsitz test p-value < 0.05).

Table 5.

Ordinal logistic regression analysis based on the question “Do you consider green spaces and urban forests a service that your local government should prioritise after the quarantine restrictions are lifted?” Respondents rated their prioritisation on a 5-point Likert scale from “very low priority” to “very high priority”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.047 | 0.103 | 0.649 | 0.954 |

| Age | −0.277 | 0.112 | 0.023** | 0.758 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | 0.052 | 0.229 | 0.822 | 1.053 |

| No | −0.064 | 0.221 | 0.774 | 0.938 |

| Urbanisation | 0.074 | 0.132 | 0.576 | 1.077 |

| Access to private green | −0.250 | 0.112 | 0.026** | 0.779 |

| Access to public green | −0.121 | 0.138 | 0.380 | 0.886 |

LR statistics (Lipsitz) = 16.901, df = 7, p-value 0.018 | AIC: 3017.467.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

Next, binary logistic regression was used to identify which independent variables predict intended changes in behaviour following the lockdown. First, we explored which factors explain intention to join a movement advocating for more green space in the city. We found that age, urbanisation, and access to public green are all useful predictors of intent to join a movement (Table 6 , p-value = 0.8083). An increase in age corresponds with an increased intent to join a movement by a factor of 0.411. Respondents in more urbanised environments were less likely to intend to join a movement by a factor of 0.332.

Table 6.

Binary logistic regression analysis based on the response “I will join a movement that is advocating for more green space in my city” to the question “Will there be any other changes in your attitude towards green spaces?”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | 0.087 | 0.098 | 0.374 | 1.091 |

| Age | 0.344 | 0.118 | 0.004** | 1.411 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | −0.022 | 0.214 | 0.918 | 0.978 |

| No | −0.133 | 0.206 | 0.519 | 0.875 |

| Urbanisation | −0.404 | 0.131 | 0.002** | 0.668 |

| Access to private green | 0.019 | 0.107 | 0.856 | 1.020 |

| Access to public green | −0.219 | 0.130 | 0.093° | 0.803 |

X-squared (Hosmer-Lemeshow) = 0.97095, df = 3, p-value = 0.8083 | AIC: 2578.5.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

In terms of intent to ask the local government for more green space, gender, age, and urbanisation level of place of residence were found to be significant variables (Table 7 , p-value = 0.4427). Intent to ask the local government for more green space decreased by a factor of 0.292 for female compared to male respondents, by a factor of 0.082 for every one (1) unit increase in age, and by a factor of 0.447 for respondents in more urbanised areas.

Table 7.

Binary logistic regression analysis based on the response “I will ask my local government for more green space in my city” to the question “Will there be any other changes in your attitude towards green spaces?”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.346 | 0.107 | 0.000*** | 0.708 |

| Age | −0.086 | 0.131 | 0.001** | 0.918 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | −0.162 | 0.230 | 0.481 | 0.850 |

| No | −0.206 | 0.222 | 0.351 | 0.813 |

| Urbanisation | −0.593 | 0.152 | 0.000*** | 0.553 |

| Access to private green | 0.116 | 0.115 | 0.315 | 1.123 |

| Access to public green | 0.082 | 0.150 | 0.585 | 1.085 |

X-squared (Hosmer-Lemeshow) = 2.6856, df = 3, p-value = 0.4427 | AIC: 2255.7.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

Finally, respondents were asked to indicate whether they intended to move to a new residence to (a) be in a greener neighbourhood (Table 8 , p-value = 0.6708) or (b) live in a residence with more private green space (Table 9 , p-value = 0.1793). Age, urbanisation, and access to private green were all found to be significant. Respondents who already have access to private green were less likely to indicate that they will move to a new residence with more private green space by a factor of 0.731. They were also less likely to want to move to a greener neighbourhood (factor 0.571). As age increased, intent to move decreased by a factor of 0.580 for intent to move to a greener neighbourhood and by 0.777 for intent to move to a residence with access to private green space. Respondents in more urbanised areas were also less likely to indicate that they intend to move to either a greener neighbourhood (factor 0.590) or to a new residence with more private green space (factor 0.551).

Table 8.

Binary logistic regression analysis based on the response “I intend to move to a new residence in a greener neighbourhood” to the question “Will there be any other changes in your attitude towards green spaces?”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.234 | 0.167 | 0.160 | 0.791 |

| Age | −0.868 | 0.237 | 0.000*** | 0.420 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | 0.086 | 0.373 | 0.818 | 1.080 |

| No | −0.037 | 0.361 | 0.919 | 0.964 |

| Urbanisation | −0.892 | 0.321 | 0.005** | 0.410 |

| Access to private green | −0.847 | 0.175 | 0.000*** | 0.429 |

| Access to public green | 0.200 | 0.230 | 0.384 | 0.818 |

X-squared (Hosmer-Lemeshow) = 1.5497, df = 3, p-value = 0.6708 | AIC: 1127.9.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

Table 9.

Binary logistic regression analysis based on the response “I intend to move to a new residence with a private green space” to the question “Will there be any other changes in your attitude towards green spaces?”. Survey population included 1987 respondents.

| Regression coefficient | SE | p-value | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male = 0, female = 1) | −0.043 | 0.166 | 0.797 | 0.958 |

| Age | −1.500 | 0.259 | 0.000*** | 0.223 |

| Care responsibilities | ||||

| Yes, shared | 0.079 | 0.367 | 0.831 | 1.082 |

| No | −0.263 | 0.357 | 0.460 | 0.768 |

| Urbanisation | −0.802 | 0.348 | 0.021** | 0.449 |

| Access to private green | −1.313 | 0.179 | 0.000*** | 0.269 |

| Access to public green | 0.036 | 0.247 | 0.885 | 1.036 |

X-squared (Hosmer-Lemeshow) = 4.8994, df = 3, p-value = 0.1793 | AIC: 1101.3.

Signif. codes: 0.001 ‘***’ 0.01 ‘**’ 0.05 ‘*’ 0.1 '°'.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This explorative study has examined changes to urban green space (UGS) use and attitudes before, during and after the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 in Belgium. A survey was distributed in spring 2020 and the response of 1987 respondents were analysed. The results showed that respondents’ understanding of their visit to and civic engagement around UGS have increased during the lockdown. In addition, it also highlighted differences between sociodemographic groups. The increase in the frequency of visits to natural areas during the COVID-19 sanitary restrictions was observed as well in other studies around the globe (Grima et al., 2020; Derks et al., 2020; Venter et al., 2020; Mackenzie and Goodnow, 2020).

The study has demonstrated that the respondents ascribed a heightened importance to recreation in green spaces and urban forests and seems to confirm general trends found in several previously published papers, while adding a distinct focus on changes in behaviour and attitude. The results of this study suggest that, while the value attributed to UGS has increased during the pandemic, it was already high before among the different groups of respondents. This finding seems to confirm the results of other studies that have found nature to be an important priority mainly for people with a higher level of education, and more so for women than for men (Lin et al., 2014; Schipperijn et al., 2010a). The findings indicate that most respondents have not altered their view on nature during the COVID-19 pandemic, but that the situation merely reinforced their beliefs. For instance, many people seemed to have shifted from giving “high priority” to UGS to “very high priority”. “Low priority” and “very low priority” hardly showed up in the results, confirming the assumption that those who took part in the survey were already sensitive to environmental topics before. The question remains as to whether this increased self-proclaimed engagement for the creation and management of UGS and nature as a place for recreation will last. Research indicates that the drastic increase in (urban) forest visits at the start of the lockdown maybe temporary effect, as counts in one study went back to normal after the first lockdown ended (Derks et al., 2020). This observed behaviour seems to contrast with the expressed intentions to go out into nature more often, also after the pandemic. Although currently difficult to prove, the quantitative evidence could be used as an indication that the self-declared behavioural changes were temporary.

We found that gender, care responsibilities, and access to a public green space were significant predictors of intended changes in UGS use, but not in attitudes towards UGS. Age was associated with both intended change in use and attitude. However, older respondents were consistently found to be less likely to change their actions or attitude but were more likely to indicate they intend to join a movement advocating for more green space in their city. Comparing population groups was possible on some levels, but due to the skewed sample this could only be done to a limited extent. The change in priority attributed to UGS was most marked in young urban populations. The expressed intent to move to a green area on the other hand was more prevalent among non-urban young people. While the study results are not decisive on the role of accessibility of UGS to underprivileged groups, they do confirm the high importance attached to them by highly educated people (cf. Kabisch et al., 2016a, 2016b). The lack of representation of respondents from different societal layers is an issue that could be addressed in a follow-up studies.

The degree of urbanisation was not found to be a significant predictor in terms of change in use but was a significant predictor of change in attitude. Respondents living in more urbanised areas were less likely to indicate they intend to join a movement, ask their local government for more green provision, or move to a new residence. Respondents who already have a private garden were less likely to say they intend to move to a new residence in a greener neighbourhood or with a private garden. They were also less likely to say they think urban green should be given high priority by the local government following the pandemic. The fact that much of Flanders can be considered an urban continuum (cf. Bruggeman, 2016) and that most of the respondents live in big and medium-sized cities may skew the detected influence of urbanity on attitude changes.

Despite the large number of responses, the generated data cannot be considered as representative for the entire Belgian population. The survey was distributed through mailing lists, social and traditional media, relying on the researchers’ social networks. This means that the sampling method was not randomised but relied on people’s personal interest and their motivation to participate in the survey. This has led to a significant overrepresentation of woman (59.29 %), 30−49-year-old respondents (48.37 % versus 26.07 % in Belgium), and higher-level educated people (85.91 % of the sample had a university degree or higher; versus 32.86 % for the Belgian population) (see Table 3, Statistics Belgium, 2020). Nonetheless, in Brussels, the living conditions of the affluent and often higher educated strongly differ from the less well educated (Degrande et al., 2014), especially when it comes to access to UGS.

Virtually, all the respondents (98 %) were from the Flemish and the Brussels region. The limited response in the southern, mostly French-speaking region of Wallonia is related to the social networks of the researchers and the limited success in outreach to French-speaking media. The shortage of respondents from different layers of society may imply a smaller interest in the matter among men, people with lesser educational attainment, or people in the younger or older age classes. An additional but untested assumption could be that the media channels that were selected to distribute the survey have more appeal among working-age educated women or that people are more positive about greening if they are convinced of its importance. The low rate of participants from lower income households limits the possibilities to make comprehensive conclusions on the impact of sociodemographic factors. The findings should be clearly interpreted with these demographic limitations in mind.

It should be considered that the study was largely exploratory, trying to discover timely information on a novel phenomenon. The exploratory nature of the research partly explains some of its limitations. Since respondents were not surveyed before the lockdown but were only asked to reflect on their use and attitudes prior to the lockdown, we cannot say whether our findings accurately reflect an actual change in use or behaviour or a self-perceived change (Fisher and Grima, 2020). Similarly, this statement remains true when referring to expressed intention to change their way of life, for instance by joining an environmental movement or by moving to a greener neighbourhood. When interpreting the data, a differentiation should be made between expressed intent and actual behavioural change. Hence a follow up of this survey would be to resample the survey population once the COVID-19 pandemic has ended to see if respondents’ anticipated changes in use and behaviour were accurate.

The general findings align with those in other studies stressing the importance of UGS in difficult times (Grima et al., 2020; Venter et al., 2020; Mackenzie and Goodnow, 2020). Still, some of the findings may be specific for the Belgian geographical and political landscape, with a highly spread-out urban tissue (cf. Poelmans and Van Rompaey, 2009). Moreover, the context of the specific measures is highly relevant to studies on COVID-19 and recreation. People in countries where outside recreation was virtually prohibited, such as Italy, Spain, France or Poland (cf. Ugolini et al., 2020), may have experienced a similar desire for nature recreation but were not able to act upon it. On the other hand, in countries with fewer limitations, such as Sweden or the Netherlands, the urge for nature recreation as the only possible leisure activity may have been less pronounced (Arslanovic and Flygt, 2020).

Despite some shortcomings, the results of this exploratory study do shed a light on the complaints and desires of (mainly urban) people during a crisis, and the role UGS play in alleviating their discomfort. In this perspective, the results could be relevant for other urbanised regions that face many of the same challenges in terms of population density and limited number of UGS and unequal access to UGS during crises yet to come. Finally, there is a strong case for on-going research with a representative sample of people who can be interviewed on an on-going basis to see how attitudes change post COVID-19.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yole DeBellis and Christiane Düring for editorial support and background research. This research was done in the frame of the CLEARING HOUSE project, which has received funding from the European H2020 Research and Innovation programme under the Grant Agreement n° 821242. Several Chinese CLEARING HOUSE partners have also contributed to the funding. The content of this document reflects only the author’s view. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Handling Editor: Wendy Chen

Appendix A. Main lockdown restrictions in Belgium

|

Appendix B. Survey questions used for this research

| Code | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Q2.2 | Which country do you live in? | |

| Q2.4 | What is your zip code/postal code? | |

| Q2.5 | What green spaces are normally available to you? | None |

| Private green | ||

| Public green | ||

| Q3.2 | How often did you visit green spaces? | |

| Before and during the quarantine | ||

| Q3.4 | For what reasons did you visit green spaces? | Not applicable |

| Before and during quarantine | ||

| Meeting people | ||

| Physical exercise | ||

| Taking kids outdoor | ||

| Reading or relaxing | ||

| Enjoying nature | ||

| Walk the dog | ||

| Getting away from the city | ||

| Other | ||

| Q3.8 | What were the barriers preventing you from visiting green spaces? | Not applicable |

| Before and during quarantine | ||

| Do not have the time | ||

| Not interested | ||

| Too far away | ||

| Do not like the available green spaces | ||

| Feel unsafe | ||

| Other | ||

| Q3.10 | Do you consider green spaces and urban forests a service that your local government should prioritize? | |

| Before, during and after quarantine | ||

| Q4.2 | How did the number of times you visited green spaces change during the time the COVID-19 pandemic affected your region? | |

| Q5.1 | How often will you visit green spaces after the coronavirus restrictions are lifted? | Considerably less than before the quarantine |

| Less than before | ||

| The same | ||

| More than before | ||

| Considerably more than before the quarantine | ||

| Q5.2 | Will there be any other changes in your attitude toward green-spaces? | I do not foresee any change |

| I intend to move to a new residence with a private green space | ||

| I intend to move to a new residence in a greener neighborhood | ||

| I will ask my local government for more green space in my city (letter, social media,…) | ||

| I will join a movement that is advocating for more green space in my city | ||

| Other | ||

| Q5.3 | Do you consider green spaces & urban forests a service that your local government should prioritize after the quarantine restrictions are lifted? | Very low priority |

| Low priority | ||

| Medium priority | ||

| High priority | ||

| Very high priority | ||

| Q6.2 | Gender | |

| Q6.3 | Age | |

| Q6.4 | Educational qualification | |

| Q6.5 | Employment | |

| Q6.6 | Did you have care giving responsibilities during the COVID quarantine? |

References

- Arslanovic A., Flygt M. 2020. Skogen – en tillflyktsort för många i virustider.https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/sodertalje/skogenblir-en-undanflykt-for-manga-i-virustider Retrieved April 6, 2020, from. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrus G., Scopelliti M., Lafortezza R., Colangelo G., Ferrini F., Salbitano F., Agrimi M., Portoghesi L., Semenzato P., Sanesi G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015;134:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- Coolen H., Meesters J. Private and public green spaces: meaningful but different settings. J Hous Built Env. 2012;27:49–67. doi: 10.1007/s10901-011-9246-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czembrowski P., Kronenberg J. Hedonic pricing and different urban green space types and sizes: insights into the discussion on valuing ecosystem services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016;146:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Davies Clive, Hansen Rieke, Rall Emily, Pauleit Stephan, Lafortezza Raffaele, Bellis Yole, Santos Artur, Tosics Iván. 2015. Green Infrastructure Planning and Implementation - The Status of European Green Space Planning and Implementation Based on an Analysis of Selected European City-Regions. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derks J., Giessen L., Winkel G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. For. Policy Econ. 2020;118(September):102253. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas O., Lennon M., Scott M. Green space benefits for health and well-being: a life-course approach for urban planning, design and management. Cities. 2017;66:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) 2013. Green Infrastructure (GI) - Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital COM (2013) 249 Final, Brussels. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (EC) COM; Brussels: 2020. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back Into Our Lives. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer L.K., Honold J., Botzat A., Brinkmeyer D., Cvejić R., Delshammar T., Elands B., Haase D., Kabisch N., Karle S.J., Lafortezza R., Nastran M., Nielsen A.B., van der Jagt A.P., Vierikko K., Kowarik I. Recreational ecosystem services in European cities: sociocultural and geographical contexts matter for park use. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018;31:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher B., Grima N. 2020. The Importance of Urban Natural Areas and Urban Ecosystem Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng D.C., Innes J., Wu W., Wang G. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on urban park visitation: a global analysis. J. For. Res. 2021;32(2):553–567. doi: 10.1007/s11676-020-01249-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannico V., Spano G., Elia M., D’Este M., Sanesi G., Lafortezza R. Green spaces, quality of life, and citizen perception in European cities. Environ. Res. 2021;196:110922. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.110922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S., Kellas A. 2020. Covid-19 Has Highlighted the Inadequate, and Unequal, Access to High Quality Green Spaces. Comment and Opinion from the BMJ’s International Community of Readers, Authors, and Editors. July 3, 2020.https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/07/03/covid-19-has-highlighted-the-inadequate-and-unequal-access-to-high-quality-green-spaces/ (Accessed 03.11.2020) [Google Scholar]

- Grima N., Corcoran W., Hill-James C., Langton B., Sommer H., Fisher B. The importance of urban natural areas and urban ecosystem services during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase A. Covid-19 as a social crisis and justice challenge for cities. Front. Sociol. 2020;5:583638. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2020.583638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase D., Larondelle N., Andersson E., Artmann M., Borgström S., Breuste J., et al. A quantitative review of urban ecosystem service assessments: concepts, models, and implementation. Ambio. 2014;43(4):413–433. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0504-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honey-Roses J., Anguelovski I., Bohigas J., Chireh V., Daher C., Konijnendijk C., Litt J., Mawani V., McCall M., Orellana A., Oscilowicz E., Sánchez U., Senbel M., Tan X., Villagomez E., Zapata O., Nieuwenhuijsen M. 2020. The Impact of COVID-19 on Public Space: A Review of the Emerging Questions. Cities & Health. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer David W., Lemeshow Stanley. Wiley; New York: 2013. Applied Logistic Regression. ISBN 978-0-470-58247-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jurkovic N.B. Perception, experience and the use of public urban spaces by residents of urban neighbourhoods. Urban Izziv. 2014;25(1):107–125. doi: 10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2014-25-01-003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch N., Haase D., Annerstedt van den Bosch M. Adding natural areas to social indicators of intra-urban health inequalities among children: a case study from Berlin, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2016;13:783. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13080783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch N., Strohbach M., Haase D., Kronenberg J. Urban green space availability in European cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016;70:586–596. doi: 10.1016/J.ECOLIND.2016.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan R., Kaplan S. Well‐being, reasonableness, and the natural environment. Appl. Psychol. Health Well. 2011;3:304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Krajter Ostoić S., Konijnendijk van den Bosch C.C., Vuletić D., Stevanov M., Živojinović I., Mutabdžija-Bećirović S., Lazarević J., Stojanova B., Blagojević D., Stojanovska M., Nevenić R., Pezdevšek Malovrh Š. Citizens’ perception of and satisfaction with urban forests and green space: results from selected Southeast European cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017;23:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lafortezza R., Carrus G., Sanesi G., Davies C. Benefits and well-being perceived by people visiting green spaces in periods of heat stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2009;8:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lin B., Fuller R., Bush R., Gaston K., Shanahan D. Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz S.R., Fitzmaurice G.M., Molenberghs G. Goodness‐of‐fit tests for ordinal response regression models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C Appl. Stat. 1996;45:175–190. doi: 10.2307/2986153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez B., Kennedy C., McPhearson T. 2020. Parks Are Critical Urban Infrastructure: Perception and Use of Urban Green Spaces in NYC During COVID-19. Preprints 2020, 2020080620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie S.H., Goodnow J. Adventure in the age of COVID-19: embracing microadventures and locavism in a post-pandemic world. Leis. Sci. 2020;0(0):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mattijssen T., Buijs A., Elands B., Arts B. The ‘green’ and ‘self’ in green self-governance – a study of 264 green space initiatives by citizens. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2018;20:96–113. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2017.1322945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil C., Parkes H., Statham R., Hochlaf D., Jung C. Institute of Public Policy Research; London: 2020. Children of the Pandemic. March 2020, https://www.ippr.org/files/2020-03/1585586431_children-of-the-pandemic.pdf (Accessed 03.11.2020) [Google Scholar]

- Mertens L., Van Cauwenberg J., Veitch J., Deforche B., Van Dyck D. Differences in park characteristic preferences for visitation and physical activity among adolescents: a latent class analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natural England . 2020. The People and Nature Survey for England: Adult Data Y1Q1 (April - June 2020) (Experimental Statistics) Official Statistics, Updated 29 October 2020.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-people-and-nature-survey-for-england-adult-data-y1q1-april-june-2020-experimental-statistics/the-people-and-nature-survey-for-england-adult-data-y1q1-april-june-2020-experimental-statistics (Accessed 03.11.2020) [Google Scholar]

- Ode Sang Å., Knez I., Gunnarsson B., Hedblom M. The effects of naturalness, gender, and age on how urban green space is perceived and used. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016;18:268–276. doi: 10.1016/J.UFUG.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ode Sang Å., Sang N., Hedblom M., Sevelin G., Knez I., Gunnarsson B. Are path choices of people moving through urban green spaces explained by gender and age? Implications for planning and management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020;49 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietilä M., Neuvonen M., Borodulin K., Korpela K., Sievänen T., Tyrväinen L. Relationships between exposure to urban green spaces, physical activity and self-rated health. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015;10:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Poelmans L., Van Rompaey A. Detecting and modelling spatial patterns of urban sprawl in highly fragmented areas: a case study in the Flanders-Brussels region. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009;93(1):10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga W., Bird N., Hallingberg B., Phillips R., Williams D. The role of perceived public and private green space in subjective health and wellbeing during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021;211:104092. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rall E., Bieling C., Zytynska S., Haase D. Exploring city-wide patterns of cultural ecosystem service perceptions and use. Ecol. Indic. 2017;77:80–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schipperijn J., Ekholm O., Stigsdotter U.K., Toftager M., Bentsen P., Kamper-Jørgensen F., Randrup T.B. Factors influencing the use of green space: Results from a Danish national representative survey. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010;95:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2009.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schipperijn J., Stigsdotter U.K., Randrup T.B., Troelsen J. Influences on the use of urban green space - a case study in Odense, Denmark. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010;9:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2009.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simon D. 2020. Cities Are at Centre of Coronavirus Pandemic – Understanding This Can Help Build a Sustainable, Equal Future. Online Article at the Conversation.https://theconversation.com/cities-are-at-centre-of-coronavirus-pandemic-understanding-this-can-help-build-a-sustainable-equal-future-136440 (Accessed 03.11.2020) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Belgium . 2020. Statistieken Bevolkingsdichtheid. Online database at StatBel – België in cijfers.https://statbel.fgov.be/nl/themas/bevolking/bevolkingsdichtheid (Accessed 05.01.2020) [Google Scholar]

- Tamosiunas A., Grazuleviciene R., Luksiene D., Dedele A., Reklaitiene R., Baceviciene M., Vencloviene J., Bernotiene G., Radisauskas R., Malinauskiene V., Milinaviciene E., Bobak M., Peasey A., Nieuwenhuijsen M.J. Accessibility and use of urban green spaces, and cardiovascular health: findings from a Kaunas cohort study. Environ. Health. 2014;13(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomao A., Secondi L., Corona P., Carrus G., Agrimi M. Exploring individuals’ well-being visiting urban and peri-urban green areas: a quantile regression approach. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia. 2016;8:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Tu G., Abildtrup J., Garcia S. Preferences for urban green spaces and peri-urban forests: an analysis of stated residential choices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016;148:120–131. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini F., Massetti L., Calaza-Martinez P., Carinanos P., Dobbs C., Krajter Ostoić S., Marin A.M., Pearlmutter D., Saaroni H., Šauliene I., Simoneti M., Verlič A., Vuletić D., Sanesi G. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: an international exploratory study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020;(56) doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini F., Massetti L., Pearlmutter D., Sanesi G. Usage of urban green space and related feelings of deprivation during the COVID-19 lockdown: lessons learned from an Italian case study. Land Use Policy. 2021;105:105437. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch M., Sang Å.O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health–a systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 2017;158:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Jagt A.P.N., Elands B.H.M., Ambrose-Oji B., Gerőházi E., Steen Møller M., Buizer M. Participatory governance of urban green spaces: trends and practices in the EU. Nord. J. Archit. Res. 2017;28:11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderstraeten L., Van Hecke E. De Vlaamse stadsgewesten, update 2017. Ruimte & Maatschappij. 2019;10(4):10–37. [Google Scholar]

- Venter Z., Barton D., Gundersen Vegard, Figari H., Nowell M. 2020. Urban Nature in a Time of Crisis: Recreational Use of Green Space Increases during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Oslo, Norway. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vujičić M., Tomićević-Dubljević J., Živojinović I. Connection between urban green areas and visitors’ physical and mental well-being. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019;40:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- Wei F. Greener urbanization? Changing accessibility to parks in China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017;157:542–552. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) WHO Regional Office for Europe; Copenhagen: 2016. Urban Green Spaces and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Žlender V., Ward Thompson C. Accessibility and use of peri-urban green space for inner-city dwellers: a comparative study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017;165:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]