Abstract

It has long been suggested that dimorphic female-limited Batesian mimicry of two closely related Papilio butterflies, Papilio memnon and Papilio polytes, is controlled by supergenes. Whole-genome sequencing, genome-wide association studies and functional analyses have recently identified mimicry supergenes, including the doublesex (dsx) gene. Although supergenes of both the species are composed of highly divergent regions between mimetic and non-mimetic alleles and are located at the same chromosomal locus, they show critical differences in genomic architecture, particularly with or without an inversion: P. polytes has an inversion, but P. memnon does not. This review introduces and compares the detailed genomic structure of mimicry supergenes in two Papilio species, including gene composition, repetitive sequence composition, breakpoint/boundary site structure, chromosomal inversion and linkage disequilibrium. Expression patterns and functional analyses of the respective genes within or flanking the supergene suggest that dsx and other genes are involved in mimetic traits. In addition, structural comparison of the corresponding region for the mimicry supergene among further Papilio species suggests three scenarios for the evolution of the mimicry supergene between the two Papilio species. The structural features revealed in the Papilio mimicry supergene provide insight into the formation, maintenance and evolution of supergenes.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Genomic architecture of supergenes: causes and evolutionary consequences’.

Keywords: supergene, transposon, chromosomal inversion, linkage disequilibrium, female-limited polymorphic mimicry, Papilio butterflies

1. General introduction

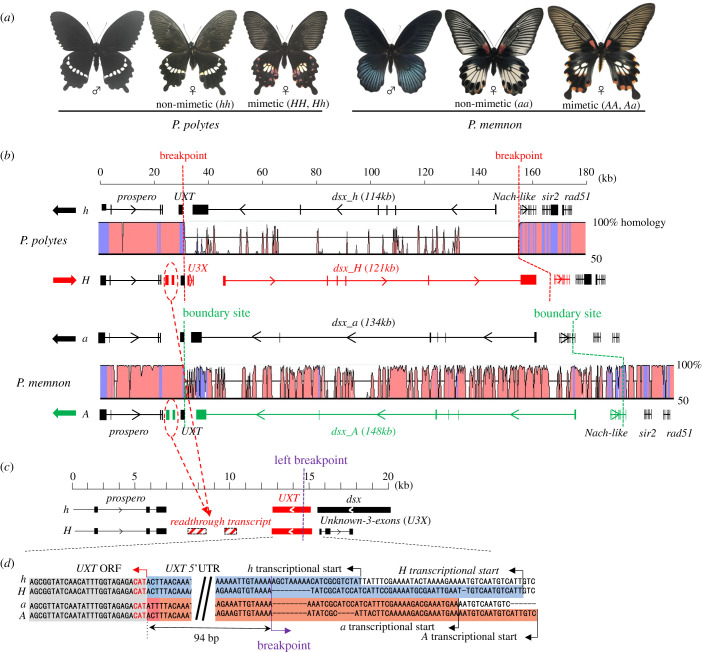

Batesian mimicry, in which non-toxic species resemble distantly related toxic species in terms of colour patterns, morphology and other traits, such as behaviour, is found in a wide range of organisms [1]. Since the era of Darwin and Wallace, polymorphic Batesian mimicry in Papilio butterflies, Papilio memnon and Papilio polytes, has been of widespread interest [2–7]. Only a portion of the female butterflies (mimetic type) mimic the poisonous model butterflies, whereas the other females (non-mimetic type) and males have different patterns (figure 1a). Genetic studies have shown that the causative locus for mimicry is predicted to be at an autosomal location (H locus for P. polytes and A locus for P. memnon), and the mimetic allele (H or A) is dominant over the non-mimetic allele (h or a) [3–5]. In addition, the above mimicry coordinates with multiple traits such as wing colour, wing shapes (absence or presence of hind-wing tails), and behaviour [10–14], which inspired early geneticists such as Fisher and Ford to hypothesize that the locus is composed of multiple flanking genes in a chromosomal locus, which is called a supergene [15,16].

Figure 1.

(a) Wing patterns of adult males and non-mimetic and mimetic females of Papilio polytes and Papilio memnon. Mimicry is regulated by the H locus for P. polytes and A locus for P. memnon, with the mimetic allele (H or A) dominant over the non-mimetic allele (h or a). (b) Comparison of the detailed structure of mimicry highly divergent regions (HDRs) in P. polytes and P. memnon [8,9]. The direction of the dsx-HDR is reversed between h and H of P. polytes, but is the same between a and A of P. memnon. Putative breakpoints of the HDRs in P. polytes or boundary sites in P. memnon are indicated using red or green dotted lines, respectively. Graphical overview of the homology between heterozygous regions is also shown. Exon regions are shown in blue. (c) Enlarged view of the 20 kb region around the left breakpoint in P. polytes. U3X is transcribed only from H. The two dotted boxes with red shaded lines indicate the read-through transcripts of prospero. Some RNA-sequencing reads were mapped on H but not on h in this region [8]. (d) An enlarged view of the 200 bp region near the left breakpoint/boundary site in P. polytes and P. memnon. UXT crosses the breakpoint/boundary site at its 5'-untranslated region (UTR) in P. polytes and P. memnon (blue and red boxes, respectively); therefore, the sequences between the transcriptional start point and 95 bp region upstream of a translational start are very different [9].

Many empirical and theoretical studies have been conducted on supergenes [15–19]. Recently, Thompson & Jiggins [20, p.3] proposed a new definition of a supergene as ‘a genetic architecture involving multiple linked functional genetic elements that allows switching between discrete and complex phenotypes maintained in a stable local polymorphism’. This new definition is broad enough to include not only multiple functional genes in a tightly linked region but also multiple genetic elements, such as cis regulatory elements, which control a single gene and switch phenotypic polymorphisms. In Papilio dardanus, for example, there is an inversion in the regulatory region between engrailed and invected, which is thought to be involved in the regulation of polymorphism in Batesian mimicry limited to females and is thought to be one of the supergenes [21]. Although there are examples which have shown that multiple genes or elements are included in the causal supergene region, there are few examples in which functional analysis or other methods have directly shown that multiple genetic elements in supergenes are involved in the regulation of phenotypic polymorphism.

It has been proposed that supergene identity is maintained by suppression of homologous chromosome recombination. Unless the recombination rate is low in regions such as the centromere, the mechanism of recombination suppression is thought to be mainly owing to genomic structural variations, such as chromosome inversions and large genomic insertions/deletions [19,22]. Chromosome inversions, ranging from approximately 100 kb to 10 Mb, occur in many intraspecific polymorphisms (table 1 in [22]). In some species, such as pea aphids and stick insects, genomic insertions occur from 100 kb to 5 Mb (table 1 in [22]). It is hypothesized that these genomic structural variants not only lead to recombination suppression and maintenance of the polymorphism but also cause new mutations responsible for adaptive supergene development [23].

In this review, we focus on mimicry in two Papilio species (i.e. P. memnon and P. polytes), which contain the most well studied supergene system from the era of Darwin and Wallace [1–9,24,25]. The two Papilio species are related to the subgenus Menelaides of the genus Papilio, and show a similar pattern of female-limited mimicry. The subgenus Menelaides also contains other female-limited mimetic polymorphisms, such as those in Papilio rumanzovia and Papilio aegeus [25]. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) using whole-genome sequencing and functional analyses have recently revealed that the causative loci and constitutive multiple genes for the mimicry supergene of P. polytes and P. memnon are nearly the same; however, their genomic architecture and gene structure are quite contrasting (e.g. P. polytes has an inversion, but P. memnon does not) [8,9,24]. There are no other examples of such a supergene in the same genomic region among closely related species, where a structural difference in the presence or absence of an inversion has been found. Therefore, Papilio mimicry in the subgenus Menelaides is an excellent system that provides important insights into the substance, origin, and evolution of supergenes. In addition, functional analyses of several genes in the causal region have recently been performed, and the details of the supergene are becoming clearer [26]. We reconsider the definition, function and origin of the supergene by reviewing the genomic architecture, conceptual unit and evolutionary processes in the mimicry supergene of Papilio species.

2. Genomic architecture of the mimicry supergene in two Papilio butterflies

The H locus responsible for Batesian mimicry in P. polytes was independently identified near the doublesex (dsx) gene in chromosome 25 (Chr.25) by two research groups [8,24]. Whole-genome sequences of a heterozygous Hh female indicated that Chr.25 includes highly divergent regions (HDRs), which represent sequence polymorphisms between homologous chromosomes. The HDR on Chr.25, which includes a whole dsx, coincides with the region identified as the H locus by means of linkage analyses using single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [8,24]. Analysis of whole-genome sequences of heterozygote individuals aided the identification of HDRs showing intraspecific polymorphisms, representing the possibility of a supergene [8]. This method has also been applied to detect HDR in the P. memnon genome. A GWAS clarified that an HDR containing dsx on Chr.25 is responsible for the A locus, which corresponds to the location of the P. polytes H locus [9]. A Harr plot, which is often used to detect inversion and gene duplication, along with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis over HDR boundary sites have revealed that mimicry HDR is not an inversion in P. memnon [9]. To clarify the genomic architecture of mimicry supergenes in P. polytes and P. memnon, we compared the HDR structures of the respective alleles (H, h, A and a), while focusing mainly on sequence homology, breakpoints/boundary sites, linkage disequilibrium (LD) and repetitive sequences.

HDR at the mimicry locus, which will be referred to as the mimicry HDR hereafter, contains a full-length dsx gene (consisting of six exons), of approximately 100 kb [8,9,24,25]. Nucleotide sequences of chromosomal regions other than HDR have nearly 100% homology between homologous chromosomes; however, there is only approximately 50–70% homology (i.e. sequence similarity) in the entire HDR (figure 1b). The breakpoint/boundary site on the left side of both mimicry HDRs in the two species is located inside the 5'-untranslated region (UTR) of the ubiquitously expressed transcript (UXT) gene (figure 1b,c,d); however, the breakpoint/boundary site on the right side is different between the two mimicry HDRs, just on the outer side of dsx in P. polytes, but inside Nach-like in P. memnon (figure 1b) [9]. The boundary site in P. memnon was manually determined by means of sequence comparison [9]. Because of this difference in breakpoint/boundary site position and the degree of repetitive sequence insertion, the mimicry HDRs of the two species differ considerably in length (H-137 kb, h-123 kb; A-168 kb, a-150 kb) [8,9] (figure 1b). In P. polytes, the HDR of the H-allele and that of h-allele are in opposite directions across the left and right breakpoints, owing to a simple inversion. The upstream of dsx is on the Nach-like side of the h-allele and on the UXT side of the H-allele (figure 1b). The h-allele type-chromosomal direction was conserved among most lepidopteran species, suggesting that the H-allele appeared from the h-allele by means of inversion. Even when the H-allele region was compared with the h-allele region in the same direction, the homology of the sequences inside HDR was low [8], suggesting that the alleles have diverged after the inversion occurred and the recombination suppression was established. By contrast, the direction of dsx in the P. memnon A-allele and a-allele is the same as that in other lepidopterans, indicating that highly diversified sequences appeared in the mimicry HDR even without chromosomal inversion in this species [9]. The presence or absence of an inversion in the above alleles has been confirmed using multiple sequencing methods for mate-pair genomic libraries, fosmid libraries, genome walking and PCR over breakpoints/boundary sites [8,9,24].

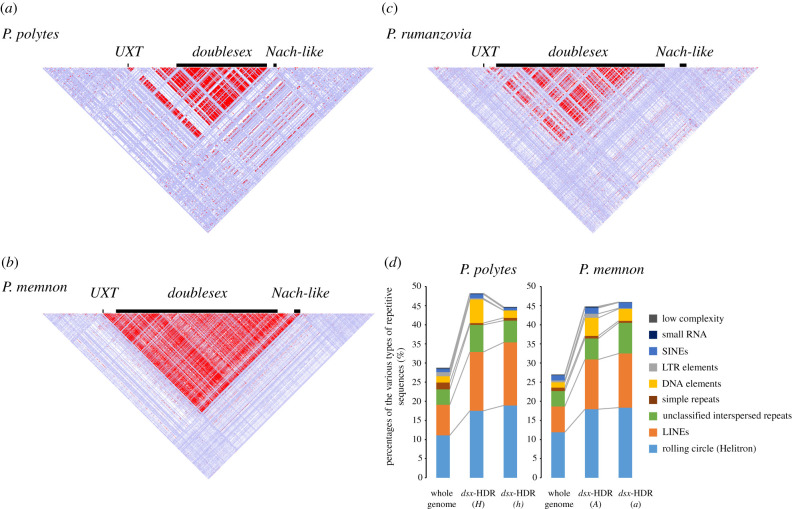

An estimated high LD, which suggests the repression of chromosomal recombination, is clearly observed around the mimicry HDR in P. polytes and P. memnon; it occurs in the region containing full-length dsx genes [8,9,24,25]. Based on whole genome sequencing data, we re-analysed the detailed positions of mimicry HDRs. The left end of the LD in the two Papilio species was similarly observed within the 5'-UTR of UXT, which is consistent with the left breakpoint/boundary site of mimicry HDRs described above (figure 2a,b). By contrast, the right end of LD was observed at the just outer side of dsx in P. polytes; however in P. memnon, LD extended to the Nach-like gene, which is located outside dsx, whose position is also similar to the right breakpoints/boundary sites in the mimicry HDRs of P. memnon described above (figure 2a,b). Furthermore, LD was observed around dsx and extended to UXT in a closely related species of P. memnon, P. rumanzovia, which shows a similar female-limited mimicry polymorphism [25] (figure 2c). However, in P. rumanzovia, the right end of the LD region was located within the dsx region (figure 2c).

Figure 2.

(a–c) Linkage disequilibrium (LD) heatmaps around the mimicry HDRs in P. polytes (a), P. memnon (b) and P. rumanzovia (c). LD across the mimicry HDR and the flanking 50 kb region. Standard colour scheme: D < 1, LOD < 2 (white); D'=1, LOD < 2 (blue); D' ≤ 1, LOD ≥ 2 (pink and red). Re-analyses were conducted using publicly available genome sequencing data [8,9,24,25,27]. Platanus-allee (v. 2.3.2) [27] was used to perform whole genome assembly using individuals of dsx genotypes Hh in P. polytes (accession number: SAMD00131361) and Aa in P. memnon (accession number: SAMD00074273). Using these as the reference genome, mapping was performed using six individuals (accession numbers: SRR1118145, SRR1118150, SRR1118152, SRR1111718, SRR1112070 and SRR1112619) for P. polytes, and 11 individuals (accession numbers: SAMD00074266–SAMD00074276) for P. memnon. Reads were mapped using BWA (v. 0.7.17-r1188) [28], single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were detected using GATK (v. 4.2.2.0) [29], and the file format of the SNV detection result was converted for Haploview [30] using PLINK (v. 1.90b6.24) [31]. The number of SNVs was set to 2000. In P. rumanzovia, LD was calculated by mapping 46 samples (accession numbers: SAMN13265081–SAMN13265107 and SAMN13265109–SAMN13265127) to the reference genome of P. memnon. (d) Percentages of the various types of repetitive sequences in the whole genome and within the mimicry HDR. The proportion of repetitive sequences was calculated using the same whole genomes, as in (a–c), with RepeatMasker (v4.0.9; www.repeatmasker.org/).

The left-side breakpoint/boundary site of the HDR is commonly located among these three species, although an inversion is present in P. polytes and absent in P. memnon and P. rumanzovia [8,9,24,25]. The conserved location of the left-side breakpoint/boundary site of HDR suggests that it plays an important role in the maintenance and function of the supergene in female-limited mimicry in this group. A review by Villoutreix et al. [23] revealed that the breakpoint of the supergene itself results in adaptive mutations. In a new gene, the long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) gene, Unknown 3 eXons (U3X), was thought to have arisen owing to an inversion in P. polytes (see §7 for more detail).

Since there is a structural difference between P. polytes and P. memnon, namely, the presence or absence of an inversion, the proportion and composition of the accumulated repetitive sequences may be different. Therefore, we re-estimated the proportion of repetitive sequences in the mimicry HDR based on newly assembled genome data. We found that the proportion of repetitive sequences in the HDRs of both P. polytes and P. memnon was 40–50% higher than that of the whole genome (figure 2d). The most common types of repetitive sequences were long interspersed nuclear elements (LINES; non-long terminal repeat retrotransposons) and rolling circle (Helitron) transposons. While there was a difference between the two species, in terms of the presence or absence of an inversion, there was no significant difference in the proportion and type of repetitive sequences: the number of repetitive sequence elements in the mimicry HDR is 368 and 433 for P. polytes and P. memnon, respectively (chi-square test: p = 0.68; figure 2d). It has been reported that transposable elements accumulate in regions where recombination is suppressed [32,33].

It is possible that in the common ancestor of P. polytes and P. memnon, an inversion occurred and mutations such as repetitive sequences accumulated, but only in P. memnon did re-inversion occur, so that the proportion and composition of repetitive sequences were similar (see §7 for more details on this evolutionary process). However, it is unknown whether the accumulation of mutations is the cause or result of supergene formation. The absence of inversions in P. memnon and P. rumanzovia suggests that recombination is suppressed by other factors, such as insertions or deletions. Although there are no major structural variations, such as large insertions of greater than or equal to 100 kb, as seen in other supergene examples, some reports have suggested that transposable elements and repetitive sequences are involved in recombination suppression [34].

The supergene of these two Papilio mimicry systems is one of the most closely studied systems, as shown above, and we have now clarified the LD region. Compared with other supergenes, the region considered to be a supergene is much smaller and contains fewer genes. The LD region is expected to be larger and contain more genes that are not related to phenotypic polymorphism, when recombination suppression mechanisms are established later owing to mutations in multiple genes than when mutations occur in multiple genes that were originally linked and evolved to act as supergenes [35]. For example, in Drummond's rockcress, Boechera stricta, 1591 genes are contained within the 8.4 Mb inversion region, and different quantitative trait loci in the inversion are involved in three different traits, which is an example of a later occurrence of inversion (i.e. recombination suppression) [36]. By contrast, in the case of the Papilio mimicry supergene, the small size of the HDR suggests that multiple mutations arose later in a region that was originally linked. Initially, recombination-suppressing structural variants (e.g. inversions) may have occurred around dsx, and multiple mutations forming the mimetic form may have arisen. In the following sections (§§3–6), we review the characteristics and expression of genes in and flanking the HDR, as well as the functional analysis using RNA interference (RNAi), to examine the functional units of the supergene.

3. Detailed characterization of genes involved in the mimicry supergene of Papilio polytes and Papilio memnon

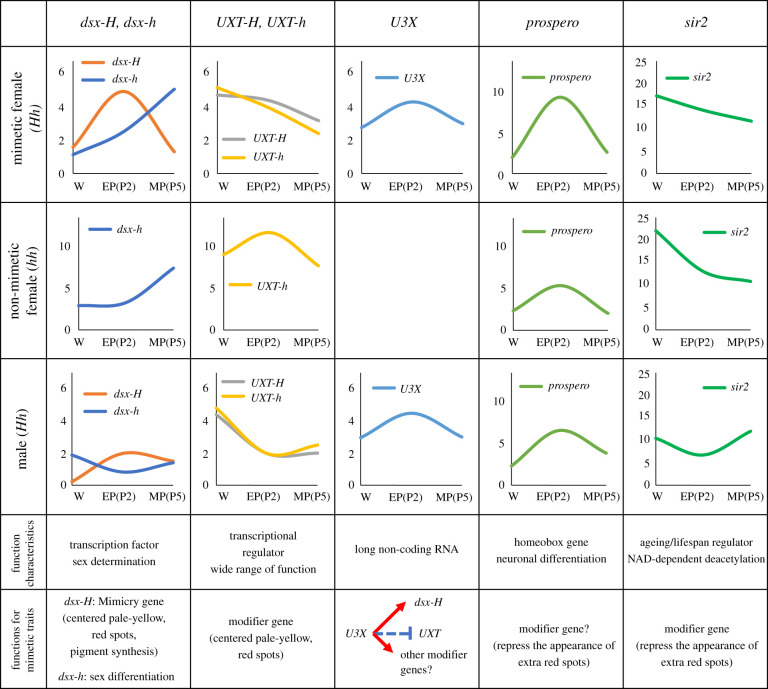

Genes in (dsx, UXT, U3X and Nach-like) and adjacent to (prospero and sir2) the HDR that may be involved in the formation of mimetic traits will be reviewed in this section, including their characteristics and the differences between mimetic and non-mimetic alleles (figure 3). The genes adjacent to the mimicry HDR (prospero and sir2) may be regulated by the influence of some enhancer or cis element inside the HDR, and have been shown to be involved in the formation of mimetic traits (see §5).

Figure 3.

Summary of expression and function of genes within and flanking the mimicry HDR in P. polytes. The expression levels of dsx-H, dsx-h, UXT-H, UXT-h, U3X, prospero and sir2 in mimetic and non-mimetic females and males of hindwings are summarized based on Komata et al. [26]. W indicates the wandering stage of the late last instar larvae; EP (P2) indicates the early pupa (2 day after pupation: P2); MP (P5) indicates the middle pupa (5 day after pupation: P5). In addition, the genetic functions and characteristics were shown. Nach-like was not included in the table because its expression in the wing has not been confirmed and its function is not known [9,26].

(a) . Internal genes within the mimicry highly divergent regions

(i) . dsx

dsx is a transcription factor that preserves some domain structures from insects to humans and controls sexual differentiation [37]. The overall length of the genomic dsx region was larger in case of the mimetic dsx (121 kb in H, 148 kb in A) than that in case of the non-mimetic dsx (114 kb in h, 134 kb in a), in both the species (figure 1b). This could be caused by the more frequent insertion of repetitive sequences into intron regions in the mimetic dsx. The sequence identities of dsx between the mimetic (H, A) and non-mimetic (h, a) alleles of the two butterflies were significantly lower in the intron and exon regions (figure 1b). Their amino acid sequences were conserved in the DNA binding and dimerization domains, but considerably divergent in other regions: 14 substitutions between H and h, and four substitutions between A and a [8,9,38]. Mutations were observed more frequently in dsx-H and dsx-h, but not in dsx-A and dsx-a. Since we could not find the same mutation residue commonly introduced between H and A, no evidence currently suggests that a specific amino acid is involved in the mimetic trait. Furthermore, since the mutated residues do not match in alignment between dsx-H and dsx-A, both mimicry traits seemed to have evolved independently in parallel or via ancestral polymorphism, and the mutations may have accumulated after speciation (allelic turnover, see §7) [9,25,38]. The dsx genes consist of six exons and five introns. There is only one isoform for dsx in males, but three isoforms (F1, F2 and F3) in females.

(ii) . UXT

UXT, also known as ART-27, was originally named for its constant expression in human and mouse tissues [39,40]. UXT is a prefoldin-like protein family that forms a folding complex of proteins and is a transcriptional regulator that has an extremely wide range of functions, such as interaction with androgen receptors, transcriptional regulation of NF-kB and induction of angiogenesis by attenuation of the Notch-signalling pathway; however, its common function that is preserved in many organisms is unknown [41,42]. Papilio polytes and P. memnon UXT have 149 amino acid residues with the same sequence, whereas the sequence homology of UXT is quite low when compared among insects. Upon comparing Papilio UXT amino acid sequences with those of human and mouse UXT, some highly conserved sequences (RYE-NFI, IGCNFF—VPDTS, KAHI-ML, etc.) have been found to be scattered. The left-side breakpoints/boundary sites of HDRs in P. polytes and P. memnon are located within the 5'-UTR of UXT. However, the upstream region sequences of UXT that are inside the HDR vary between H and h, or A and a, suggesting that transcriptional regulation is significantly different between mimetic UXT and non-mimetic UXT.

(iii) . U3X

In the HDR of the P. polytes H allele, an lncRNA gene, U3X, consisting of three exons (99b, 236b and 265b), resides between UXT and dsx-H [8]. U3X is 2.2 kb in total length, located only 871 bp upstream from the transcription start site of UXT in the opposite direction, and upstream of dsx-H in the same direction, suggesting that U3X may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of both genes. The lncRNA upstream of dsx in Daphnia magna is involved in regulating dsx expression, suggesting a similar function for U3X [43,44]. In fact, U3X may regulate dsx and UXT expression in P. polytes (§6). Since no homologous sequence of U3X is found in h-HDR and other genomic regions of P. polytes, U3X appears to be a new-born gene formed at the time of H-HDR appearance or afterwards. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses have shown that U3X has several isoforms based on alternative splicing; however, the second exon is commonly included in all transcripts.

(iv) . Nach-like

Nach-like was initially unannotated in the P. polytes genome analyses, but was later identified as a gene similar to the nach (sodium channel) family between dsx and sir2 genes [19]. Nach is also known as the super family gene degenerin/epithelial sodium channels (DEG/ENaC) and as pick pocket (ppk) family genes (approx. 600 genes found in insects), which are involved in broader functions primarily related to nerves and behaviour, including the detection of mechanical and chemical stimuli [45,46]. Nach-like is considered to have a relatively close homology to Drosophila ppk5, whose function has not yet been clarified. In P. memnon, the amino acid sequence of Nach-like between the A-allele and a-allele is changed at 10 sites up to the first seven exons, but is the same after the eighth exon, which coincides with the fact that the right end of the HDR resides in the seven introns. The amino acid sequence of Nach-like is relatively conserved between P. polytes and P. memnon; however, the sequence and length of Nach-like are considerably different, even among Papilio species such as Papilio machaon, Papilio xuthus and P. dardanus [9].

(b) . Flanking genes in mimicry highly divergent regions

(i) . prospero

Downstream of the transcriptional direction of UXT (left side of UXT) is a homeobox gene, prospero. It is known that prospero controls the expression of other genes, such as ftz, eve, en and Dfd, diverse proper neuronal differentiation, axonal outgrowth and neuronal pathfinding in the central and peripheral nervous systems [47]. Between UXT and prospero, we found read-through transcripts of prospero, which are expressed only in the mimetic alleles (H and A), but not in the non-mimetic alleles (h and a) (figure 1c), suggesting that they may be involved in the mimicry trait [8]. To clarify the functional role of the above mimicry-specific transcripts, it could be relevant to study their expression and function in the brain.

(ii) . sir2

Adjacent to Nach-like, in the downstream direction of its transcription, is the sir2 gene, which is known as an ageing/lifespan regulator in a wide range of animals [48,49]. Sir2 has NAD-dependent deacetylation activity, interacts with the insulin-signalling pathway, and converts the energy state of cells into a chromatin-regulated state in the genome [50].

4. Expression patterns of genes in and flanking the mimicry supergene in Papilio polytes

The well-studied expression patterns of the above six genes in P. polytes have been reviewed in this section. In P. polytes, the formation and pigmentation of mimetic traits begin around the ninth day after pupation (P9) [51], so the expression in the late last instar larvae and early pupal stage may be related to the formation of mimetic traits [8]. Therefore, we will outline the expression data generated using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RNA-seq, mainly in the wandering stage (W) when pre-pupa starts, early pupal stage (2 days after pupation: P2), and mid-pupal stage (5 days after pupation: P5) (figure 3).

(a) . dsx expression pattern and mimicry traits

In the hind wings of P. polytes, both dsx-H and dsx-h are rarely expressed in males (Hh), from the pre-pupal to pupal stages (figure 3) [8,52]. However, in mimetic female (Hh) hind wings, dsx-H, whose expression pattern is responsible for inducing mimetic traits, is strongly expressed in early pupal stages, although dsx-h is expressed in later pupal stages, suggesting that some cis factors inside the mimicry HDR induce mimetic dsx expression in hind wings in a female-specific manner (figure 3) [8,26]. Three female isoforms of dsx, F1, F2 and F3, are almost uniformly expressed, although F3 tends to be relatively large in the hind wings of P. polytes [8,26,52]. No male-specific isoform of dsx is expressed in the female wings [52]. dsx expression is very high in the gonads (ovaries or testes) and has been observed in flight muscles and brains [53], whereas the involvement of the latter in behavioural mimicry should be further studied.

(b) . Expression patterns of other genes in and flanking the mimicry highly divergent regions

Both UXTs, transcribed from H and h alleles, are constantly expressed and tend to be higher in the wandering and earlier pupal stages in the mimetic female (Hh) hind wings of P. polytes (figure 3) [26]. U3X is also constantly expressed and tends to be higher in the earlier pupal stages in Hh female wings (figure 3). The H-specific gene U3X is not expressed in non-mimetic hh females [8,26]. Nach-like expression is not detected during pupal stages in wings and tissues other than the gonads (ovaries or testes) [9,26]. prospero in Hh female wings of P. polytes shows strong expression in the early pupal stages (figure 3) [26]. In addition, sir2 is constantly expressed and tends to be higher in the wandering stage, when pre-pupa starts, and in earlier pupal stages, in mimetic female (Hh) hind wings of P. polytes (figure 3) [26]. The higher expression of UXT and sir2 suggests that they may be involved in mimetic traits in stages earlier than pupation.

5. Functional analyses of genes in and flanking the mimicry supergene in Papilio polytes

Recently, we developed a rapid technique to analyse gene function and phenotypic changes in butterfly wings using RNAi with small interfering RNA (siRNA) injection, and then transferring siRNA into cells by means of electroporation, immediately after pupal ecdysis [53,54]. When mimetic dsx-H was knocked down using this method in the hind wings of mimetic females of P. polytes, the wing phenotype changed into a non-mimetic pattern: the centred pale-yellow region changed to a top flattened shape, with appearance of pale-yellow spots characteristic of the non-mimetic pattern, while peripheral red spots were shrunken [8]. Among the three female dsx-H isoforms, only F3 knockdown was effective in switching the patterns [26]. This result indicates that mimetic traits are suppressed and non-mimetic traits are induced, and that the patterns can be converted even after pupal ecdysis.

Notably, the colour, shape and UV response of the pale-yellow region in P. polytes hind wings differ between mimetic and non-mimetic phenotypes. The former reflects UV light, while the latter absorbs UV light and emits blue fluorescence. The non-mimetic pale-yellow pigment is mainly composed of papiliochrome II, a compound of kynurenine and N-beta alanyl dopamine (NBAD) [51,55,56]. It absorbs UV light and emits a blue fluorescent colour, whereas the mimetic pale-yellow pigment is chemically different and has not yet been clearly identified. Knockdown of dsx-H switches the UV response from mimetic to non-mimetic types, indicating that pigment synthesis pathways are regulated mainly by dsx-H [57]. It is difficult to distinguish between male and non-mimetic females by observing the visible colour of hind wings in P. polytes; however, the number of pale-yellow spots with UV response differs between them [26]. Double knockdown of dsx-H and dsx-h in mimetic females (Hh) or knockdown of dsx-h in non-mimetic females (hh) caused hind wings with male-type pale yellow spots [26]. This suggests that dsx-h alters the male-type wings to a non-mimetic female pattern and that dsx-H causes the mimetic female pattern in P. polytes (figure 3). In addition, in P. polytes mimetic forewings, Dsx antibody staining shows a localization pattern in the many white streaks that resemble the poisonous model [24]. Thus, dsx is likely to be the most important function in mimicry formation in P. polytes. Charlesworth [35] called such a gene a mimicry gene and predicted that it arose as the initial mutation during the evolution of mimicry. By contrast, genes that improve mimicry and make minor adjustments to mimetic traits are known as modifier genes [35].

Knockdown of genes in and flanking the mimicry HDR, other than dsx, cause some changes in the mimetic traits of the mimetic wings [26]. Knockdown of UXT changed the pale-yellow region from mimetic- to non-mimetic-like patterns and shrank the peripheral red spots [26]. Knockdown of U3X elongated the pale-yellow region and red spots, mostly inside the mimetic hind wings [26]. prospero knockdown showed no remarkable change in wing patterns, with red spots possibly becoming slightly larger [26]. sir2 knockdown elongated the red spots, mostly inside the mimetic hind wings [26]. UXT, sir2 and prospero may function as modifier genes to improve mimetic traits (figure 3). However, the changes caused by lncRNA U3X knockdown may be owing to the regulation of the expression of other genes (figure 3). Some lncRNAs regulate gene expression through diverse mechanisms [58].

6. Gene networks among dsx, UXT, U3X and their downstream genes in Papilio polytes

Three genes in the mimicry HDR, a transcription factor dsx-H, a transcriptional regulator UXT, and an unknown lncRNA U3X, are considered to induce mimetic traits. A recent RNA-seq analysis showed that although dsx-H and UXT knockdown did not change the expression levels of other genes in and flanking the HDR, U3X knockdown decreased the expression of dsx-H and increased the expression of UXT (figure 3) [26]. This suggests that U3X is involved in the formation of mimetic traits, by regulating dsx-H and UXT expression.

In addition, their downstream target genes were investigated to clarify the molecular mechanism and evolution of female-limited Batesian mimicry. Among the genes whose expression was repressed by dsx-H, UXT and U3X knockdown (i.e. dsx-H-, UXT- and U3X-inducible genes), functional analyses showed that some Wnt family genes, wnt1 and wnt6, are involved in the formation of pale yellow and red spots [59]. In addition, a zinc-finger transcription factor family gene, rotund (rn), is involved in pigment synthesis pathways: knockdown of rn switched the UV response from mimetic to non-mimetic types, in pale yellow spots [26]. Some homeobox genes, such as aristaless, cut and empty spiracles, are involved in the mimetic wing patterns. By contrast, the homeobox gene abdA, whose expression is induced by dsx-H knockdown, is involved in non-mimetic wing pattern formation [59].

As described above, some genes in pigment-forming pathways are also regulated by the mimetic dsx. When dsx-H is knocked down in the mimetic female wings, the expression of genes involved in NBAD synthesis, ebony, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and dopa decarboxylase (DDC), and genes involved in kynurenine, kynurenine formamidase (Kf) and vermilion, are upregulated [57]. This indicates that dsx-H represses papiliochorome II synthesis genes in the mimetic female wings. Its repression is released in non-mimetic female wings, which causes a difference in UV responses between the two types of female wings. dsx-H has dual functional roles through downstream gene pathways, in the formation of mimetic wings and suppression of non-mimetic wings.

7. Origin and evolution of supergenes in Papilio polytes and Papilio memnon

Functional analysis of genes revealed that genes in the HDR and flanking genes are involved in mimicry type formation in P. polytes. In this section, we examine the evolutionary scenario of mimicry supergenes based on the available information (i.e. phylogenetic tree of dsx, presence or absence of an inversion and differences in LD regions) for the subgenus Menelaides.

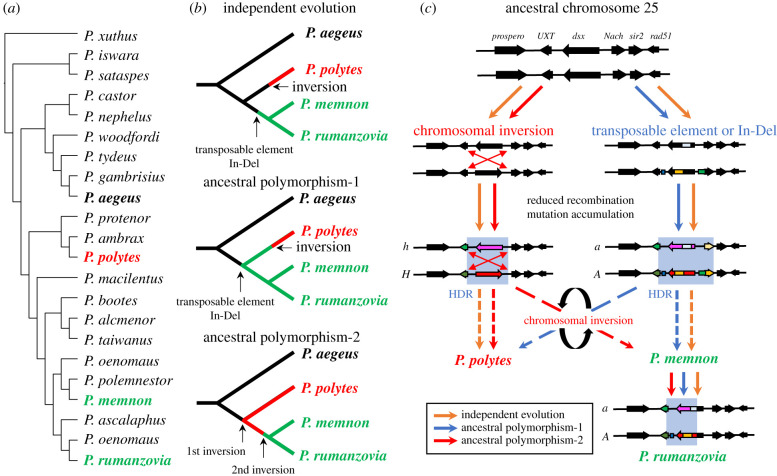

The subgenus Menelaides includes P. polytes and P. memnon, as well as P. rumanzovia and P. aegeus, which show similar types of female-limited mimicry polymorphisms and are an interesting group for exploring the evolution of the supergene [6,25,60] (figure 4a). Although dsx is also reported to be involved in the regulation of polymorphism in P. rumanzovia, which is closely related to P. memnon, there is no inversion involving the entire dsx, as seen in P. polytes [25]. However, it is unclear whether dsx is involved in mimicry polymorphisms in P. aegeus [25]. In P. dardanus, a distant relative of the same genus, the female-limited mimicry polymorphism is regulated in a completely different genomic region, other than that around the dsx gene [21,61–64], suggesting that the regulation of mimicry polymorphism around dsx is unique to the subgenus Menelaides.

Figure 4.

(a) A sketch of the phylogeny and occurrence of female-limited mimicry polymorphism in the subgenus Menelaides of the genus Papilio. The cladogram is drawn based on [25]. Species in bold show female-limited mimicry polymorphism. The inversion in the mimicry HDR is present in P. polytes (red) and absent in P. memnon (green) and P. rumanzovia (green). Papilio xuhus is an outgroup. (b) Three possible genealogies under female-limited mimicry polymorphism in the subgenus Menelaides. The causative locus for polymorphism in P. aegeus is not clear, and the evolutionary scenarios among P. polytes, P. memnon, and P. rumanzovia are shown. (c) Model diagram of the evolutionary process in the mimicry HDR of P. polytes, P. memnon and P. rumanzovia. There are three processes depending on when the inversion occurs. In the case of independent evolution, the mimetic allele (H/A) first arises independently with a chromosome inversion or without an inversion (by transposable element or In-Del) at chromosome 25. The differentiation of the mimetic allele by a chromosome inversion is in P. polytes, while the differentiation without an inversion is in P. memnon and P. rumanzovia. In terms of the ancestral polymorphism-1, the mimetic alleles initially differentiate without an inversion in the common ancestor of the three species, followed by a chromosome inversion, resulting in the P. polytes mimetic allele. Furthermore, in ancestral polymorphism-2, the first inversion in the common ancestor, followed by re-inversion, is considered to be the mimetic allele of P. memnon. The left breakpoint/boundary site of the HDR is preserved, as shown in §2 and figure 2. In P. rumanzovia, the right boundary site is shifted to the left, resulting in a smaller HDR than in P. memnon. Red arrows indicate independent evolution, blue arrows indicate ancestral polymorphism-1, and red arrows indicate ancestral polymorphism-2, as discussed in figure 4b.

Iijima et al. [9] predicted that the two Papilio species, P. polytes and P. memnon, may have evolved independently based on the comparison of genome structures (i.e. presence or absence of an inversion), amino acid substitutions, and the presence or absence of U3X. On the other hand, Palmer & Kronforst [25] compared the whole genome sequences and dsx sequences of about 20 species of butterflies in the subgenus Menelaides and argued that ancestral polymorphism was plausible and allelic turnover occurred as an evolutionary process [25,65]. The phylogenetic tree of dsx has the same genealogy as that of independent evolution; however, the branch length of dsx in mimetic and non-mimetic alleles is longer, which is consistent with the prediction of allelic turnover [25]. Nevertheless, there are other factors to be considered when estimating the evolutionary process of the supergene in the subgenus Menelaides, such as the presence or absence of an inversion and differences in gene composition (i.e. the presence or absence of U3X). In addition, for example in P. rumanzovia, there are few SNPs associated with wing polymorphisms in the region corresponding to the coding region (open reading frame) of dsx (exons 1–4) [25], and the region is not in LD (figure 2c). Therefore, it is unclear whether dsx is involved in maintaining wing polymorphism in P. rumanzovia. Regarding the three species, P. polytes, P. memnon, and P. rumanzovia, we believe that we should first divide them into two groups: P. polytes and P. memnon + P. rumanzovia groups. As mentioned above, P. polytes have an inversion and U3X, but P. memnon and P. rumanzovia do not have an inversion and U3X. In addition, it has been reported that the mimetic and non-mimetic alleles in P. memnon and P. rumanzovia have many common SNPs in dsx (but most SNPs are likely to be in introns). Based on these facts, there are three main scenarios for the evolutionary process of female-limited mimicry in the Menelaides subgenus (figure 4b). In the first scenario, P. memnon + P. rumanzovia and P. polytes groups evolved independently (figure 4b: independent evolution). As mentioned above, there are no common amino acid substitutions between P. polytes and P. memnon, and differences such as the presence or absence of inversions corroborate the independent evolution theory. The other two scenarios are ancestral polymorphisms, which are similar to the allelic turnover hypothesis proposed by Palmer & Kronforst [25], but have been divided into two groups on the basis of the type of recombination suppression mechanism: a female-limited mimicry polymorphism may have evolved in the common ancestor of the three species and an inversion may have occurred only in P. polytes (figure 4b: ancestral polymorphism-1), or an inversion may have occurred in the common ancestor of the three species and then inversed again only in the P. memnon and P. rumanzovia groups (figure 4b: ancestral polymorphism-2). All three scenarios are plausible (figure 4c). Regarding ‘ancestral polymorphism-2’, it is conceivable that an inversion could occur again at the same site if the inversion is caused by ectopic homologous recombination at transposons or other duplicated sequences [66,67]. Although we showed more accumulated repetitive sequences in the HDR (figure 2d), it would be necessary to consider the arrangement and type of repetitive sequences around the HDR in more detail. The origin of U3X is also an indispensable factor that explains the evolutionary process of mimicry supergenes. U3X is present only in P. polytes with inversions, suggesting that the recombination-suppressing region may have first formed without inversions (i.e. HDR in P. memnon), and later inversions occurred only in P. polytes. To date, U3X has not been found in any species other than P. polytes, and thus, it is necessary to investigate whether U3X is present in closely related species.

8. Conclusion

The Papilio mimicry supergene may be more complex than previously thought, both in concept and evolutionary models. Thompson & Jiggins [20] proposed that multiple genetic elements in linkage are supergenes, but functional analysis in P. polytes suggested that not only recombination-suppressed regions but also genes in recombination-unsuppressed regions are involved in mimicry traits. These genes are thought to be modifiers. These modifier genes may play a role in improving the mimicry phenotype, which is consistent with the new supergene evolutionary model proposed by Charlesworth [35]. Upon a review of theoretical models of supergene evolution, Charlesworth [35] presented two models for the Batesian mimicry supergene. She thought that the first mutation (in the mimicry gene) produced an initial mimetic phenotype, followed by one or more further genetic changes involving mutations (in the modifier gene), thus improving the initial mimicry. The first classical model states that multiple genes (e.g. mimicry and modifier genes) in the recombinant suppressed region control mimetic traits (fig. 1a in [35]). The other, newer model suggests that a single mimicry gene (mimicry gene) and the modifier genes are not linked (fig. 1b in [35]). Whether the modifier gene is included in the recombination-suppressed region depends on whether the recombinant genotypes suffer some disadvantages [35]. However, sir2 and prospero, which are outside the recombination-suppressed region, may be regulated by elements in the HDR region, because these genes are located around dsx-HDR. Although no difference in sir2 and prospero expression has been reported between mimetic and non-mimetic females, it is possible that the expression level varies slightly depending on the developmental stage and wing region, and a more detailed analysis is needed.

As we have reviewed, the Papilio mimicry supergene is an interesting system in which closely related species show similar mimicry polymorphisms, but different genetic structures. In addition, RNAi methods using in vivo electroporation have been now established, which allow for the functional analysis of wings with relative ease. We believe that the functional units and evolutionary mechanisms of the supergene will be clarified by analysing the genomic structures and gene functions related to the supergene in more Papilio butterflies.

Data accessibility

Re-analyses are conducted using raw sequencing data deposited in NCBI BioProject PRJNA234541 (SRR1118145, SRR1118150, SRR1118152, SRR1111718, SRR1112070, SRR1112619), PRJDB7193 (SAMD00131361), PRJDB5519 (SAMD00074266–SAMD00074276) and PRJNA589019 (SAMN13265081–SAMN13265107, SAMN13265109–SAMN13265127).

Authors' contributions

S.K.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; R.K.: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; T.I.: data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; H.F.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology/Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (20017007, 22128005, 15H05778, 18H04880, 20H04918, 20H00474 to H.F.; 19J00715 to S.K.).

References

- 1.Bates HW. 1862. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley (Lepidoptera: Heliconidae). Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23, 495-556. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace AR. 1865. On the phenomena of variation and geographical distribution as illustrated by the Papilionidae of the Malayan Region. Trans. Linn. Soc. (Lond.) 25, 1-71. ( 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1865.tb00178.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke CA, Sheppard PM. 1972. The genetics of the mimetic butterfly Papilio polytes L. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 26, 431-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke CA, Sheppard PM, Thornton IWB. 1968. The genetics of the mimetic butterfly Papilio memnon L. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 254, 37-89. ( 10.1098/rstb.1968.0013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke CA, Sheppard PM. 1971. Further studies on the genetics of the mimetic butterfly Papilio memnon L. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 263, 35-70. ( 10.1098/rstb.1971.0109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kunte K. 2009. The diversity and evolution of Batesian mimicry in Papilio swallowtail butterflies. Evolution 63, 2707-2716. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00752.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunte K. 2009. Female-limited mimetic polymorphism: a review of theories and a critique of sexual selection as balancing selection. Anim. Behav. 78, 1029-1036. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.08.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishikawa H, et al. 2015. A genetic mechanism for female-limited Batesian mimicry in Papilio butterfly. Nat. Genet. 47, 405-409. ( 10.1038/ng.3241) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iijima T, Kajitani R, Komata S, Lin C-P, Sota T, Itoh T, Fujiwara H. 2018. Parallel evolution of Batesian mimicry supergene in two Papilio butterflies, P. polytes and P. memnon. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao5416. ( 10.1126/sciadv.aao5416) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohsaki N. 2005. A common mechanism explaining the evolution of female-limited and both-sex Batesian mimicry in butterflies. J. Anim. Ecol. 74, 728-734. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00972.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura T, Imafuku M. 2015. Behavioural mimicry in flight path of Batesian intraspecific polymorphic butterfly Papilio polytes. Proc. R. Soc. B 282, 20150483. ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.0483) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westerman EL, Letchinger R, Tenger-Trolander A, Massardo D, Palmer D, Kronforst MR. 2018. Does male preference play a role in maintaining female limited polymorphism in a Batesian mimetic butterfly? Behav. Processes 150, 47-58. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2018.02.014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerman EL, Antonson N, Kreutzmann S, Peterson A, Pineda S, Kronforst MR, Olson-Manning CF. 2019. Behaviour before beauty: signal weighting during mate selection in the butterfly Papilio polytes. Ethology 125, 565-574. ( 10.1111/eth.12884) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komata S, Kitamura T, Fujiwara H. 2020. Batesian mimicry has evolved with deleterious effects of the pleiotropic gene doublesex. Sci. Rep. 10, 21333. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-78055-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher RA. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlesworth D, Charlesworth B. 1975. Theoretical genetics of Batesian mimicry II. Evolution of supergenes. J. Theoretic. Biol. 55, 305-324. ( 10.1016/S0022-5193(75)80082-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joron M, et al. 2011. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477, 203-206. ( 10.1038/nature10341) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang YC, Shoemaker D, Keller L. 2013. A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493, 664-668. ( 10.1038/nature11832) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwander T, Libbrecht R, Keller L. 2014. Supergenes and complex phenotypes. Curr. Biol. 24, R288-R294. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2014.01.056) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson MJ, Jiggins CD. 2014. Supergenes and their role in evolution. Heredity 113, 1-8. ( 10.1038/hdy.2014.20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timmermans MJTN, Srivathsan A, Collins S, Meier R, Vogler AP.. 2020. Mimicry diversification in Papilio dardanus via a genomic inversion in the regulatory region of engrailed–invected. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20200443. ( 10.1098/rspb.2020.0443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutiérrez-Valencia J, Hughes PW, Berdan EL, Slotte T. 2021. The genomic architecture and evolutionary fates of supergenes. Genom. Biol. Evol. 13, evab057. ( 10.1093/gbe/evab057) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villoutreix R, Ayala D, Joron M, Gompert Z, Feder JL, Nosil P. 2021. Inversion breakpoints and the evolution of supergenes. Mol. Ecol. 30, 2738-2755. ( 10.1111/mec.15907) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, Mullen SP, Kronforst MR. 2014. doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature 507, 229-232. ( 10.1038/nature13112) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmer DH, Kronforst MR. 2020. A shared genetic basis of mimicry across swallowtail butterflies points to ancestral co-option of doublesex. Nat. Commun. 11, 6. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-13859-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komata S, Yoda S, KonDo Y, Shinozaki S, Tamai K, Fujiwara H. 2022. Functional involvement of multiple genes as members of the supergene unit in the female-limited Batesian mimicry of Papilio polytes. bioRxiv 2022.02.21.480812. ( 10.10.1101/2022.02.21.480812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Kajitani R, et al. 2019. Platanus-allee is a de novo haplotype assembler enabling a comprehensive access to divergent heterozygous regions. Nat. Commun. 10, 1702. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-09575-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754-1760. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna A, et al. 2010. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next- generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297-1303. ( 10.1101/gr.107524.110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. 2004. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21, 263-265. ( 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Purcell S, et al. 2007. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559-575. ( 10.1086/519795) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolgin ES, Charlesworth B. 2008. The effects of recombination rate on the distribution and abundance of transposable elements. Genetics 178, 2169-2177. ( 10.1534/genetics.107.082743) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kent TV, Uzunović J, Wright SI. 2017. Coevolution between transposable elements and recombination. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 372, 20160458. ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li SF, Zhang GJ, Yuan JH, Deng CL, Gao WJ. 2016. Repetitive sequences and epigenetic modification: inseparable partners play important roles in the evolution of plant sex chromosomes. Planta 243, 1083-1095. ( 10.1007/s00425-016-2485-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charlesworth D. 2016. The status of supergenes in the 21st century: recombination suppression in Batesian mimicry and sex chromosomes and other complex adaptations. Evol. Applica. 9, 74-90. ( 10.1111/eva.12291) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CR, et al. 2017. Young inversion with multiple linked QTLs under selection in a hybrid zone. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1-13. ( 10.1038/s41559-016-0001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baker BS. 1989. Sex in flies: the splice of life. Nature 340, 521-524. ( 10.1038/340521a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Komata S, Lin CP, Iijima T, Fujiwara H, Sota T. 2016. Identification of doublesex alleles associated with the female-limited Batesian mimicry polymorphism in Papilio memnon . Sci. Rep. 6, 34782 ( 10.1038/srep34782) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schroer A, Schneider S, Ropers H, Nothwang H. 1999. Cloning and characterization of UXT, a novel gene in human Xp11, which is widely and abundantly expressed in tumor tissue. Genomics 56, 340-343. ( 10.1006/geno.1998.5712) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sánchez-Morgan N, Kirsch KH, Trackman PC, Sonenshein GE. 2017. UXT Is a LOX-PP interacting protein that modulates estrogen receptor alpha activity in breast cancer cells. J. Cell Biochem. 118, 2347-2356. ( 10.1002/jcb.25893) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou Y, Ge R, Wang R, Liu F, Huang Y, Liu H, Hao Y, Zhou Q, Wang C. 2015. UXT potentiates angiogenesis by attenuating Notch signaling. Development 142, 774-786. ( 10.1242/dev.112532) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su SK, Li CY, Lei PJ, Wang X, Zhao QY, Cai Y, Wang Z, Li L, Wu M. 2016. The EZH1-SUZ12 complex positively regulates the transcription of NF-kB target genes through interaction with UXT. J. Cell Sci. 129, 2343-2353. ( 10.1242/jcs.185546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato Y, Perez CAG, Ishak NSM, Nong QD, Sudo Y, Matsuura T, Wada T, Watanabe H. 2018. A 5′ UTR-overlapping LncRNA activates the male-determining gene doublesex1 in the crustacean Daphnia magna. Curr. Biol. 28, 1811-1817. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.04.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez CAG, Adachi S, Nong QD, Adhitama N, Matsuura T, Natsume T, Wada T, Kato Y, Watanabe H. 2021. Sense-overlapping lncRNA as a decoy of translational repressor protein for dimorphic gene expression. PLoS Genet. 17, e1009683. ( 10.1371/journal.pgen.1009683) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zelle KM, Lu B, Pyfrom SC, Ben-Shahar Y. 2013. The genetic architecture of degenerin/epithelial sodium channels in Drosophila. G3 3, 441-450. ( 10.1534/g3.112.005272) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Latorre-Estivalis JM, Almeida FC, Pontes G, Dopazo H, Barrozo RB, Lorenzo MG. 2021. Evolution of the insect PPK gene family. Genome. Biol. Evol. 13, evab185. ( 10.1093/gbe/evab185) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan B, Li L, Bremer KA, Chang W, Pinsonneault J, Vaessin H. 1997. Prospero is a panneural transcription factor that modulates homeodomain protein activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 10 991-10 996. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10991) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guarente L. 2001. SIR2 and aging–the exception that proves the rule. Trends Genet. 17, 391-392. ( 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02339-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hoffmann J, Romey R, Fink C, Yong L, Roeder T. 2013. Overexpression of Sir2 in the adult fat body is sufficient to extend lifespan of male and female Drosophila. Aging (Albany NY) 5, 315-327. ( 10.18632/aging.100553) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imai SI, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. 2000. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature 403, 795-800. ( 10.1038/35001622) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishikawa H, Iga M, Yamaguchi J, Saito K, Kataoka H, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Fujiwara H. 2013. Molecular basis of the wing coloration in a Batesian mimic butterfly, Papilio polytes. Sci. Rep. 3, e3184. ( 10.1038/srep03184) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deshmukh R, Lakhe D, Kunte K. 2020. Tissue-specific developmental regulation and isoform usage underlie the role of doublesex in sex differentiation and mimicry in Papilio swallowtails. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 200792. ( 10.1098/rsos.200792) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujiwara H, Nishikawa H. 2016. Functional analysis of genes involved in color pattern formation in Lepidoptera. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 17, 16-23. ( 10.1016/j.cois.2016.05.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ando T, Fujiwara H. 2013. Electroporation-mediated somatic transgenesis for rapid functional analysis in insects. Development 140, 454-458. ( 10.1242/dev.085241) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stavenga DG, Matsushita A, Arikawa K. 2015. Combined pigmentary and structural effects tune wing scale coloration to color vision in the swallowtail butterfly Papilio xuthus. Zool. Lett. 1, 1-10. ( 10.1186/s40851-015-0015-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rembold H, Umebachi Y. 1985. The structure of papiliochrome II, the yellow wing pigment of the Papilionid butterflies. In Progress in tryptophan and serotonin research (eds Schlossberger HG, Kochen W, Linzen B, Steinhart H), pp. 743-746. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoda S, et al. 2021. Genetic switch in UV response of mimicry-related pale-yellow colors in Batesian mimic butterfly, Papilio polytes. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6475. ( 10.1126/sciadv.abd6475) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marchese FP, Raimondi I, Huarte M. 2017. The multidimensional mechanisms of long noncoding RNA function. Genome Biol. 18, 1-13. ( 10.1186/s13059-017-1348-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iijima T, Yoda S, Fujiwara H. 2019. The mimetic wing pattern of Papilio polytes butterflies is regulated by a doublesex-orchestrated gene network.. Commun. Biol. 2, 1-10. ( 10.1038/s42003-019-0510-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zakharov EV, Caterino MS, Sperling FA. 2004. Molecular phylogeny, historical biogeography, and divergence time estimates for swallowtail butterflies of the genus Papilio (Lepidoptera: Papilionidae). Sys. Biol. 53, 193-215. ( 10.1080/10635150490423403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.VanKuren NW, Massardo D, Nallu S, Kronforst MR. 2019. Butterfly mimicry polymorphisms highlight phylogenetic limits of gene reuse in the evolution of diverse adaptations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 2842-2853. ( 10.1093/molbev/msz194) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Clarke CA, Sheppard PM. 1960. The genetics of Papilio dardanus Brown. II. Races dardanus, polytrophus, meseres, and tibullus. Genetics 45, 439-456. ( 10.1093/genetics/45.4.439) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clark R, Brown SM, Collins SC, Jiggins CD, Heckel DG, Vogler AP. 2008. Colour pattern specification in the mocker swallowtail Papilio dardanus: the transcription factor invected is a candidate for the mimicry locus H. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 1181-1188. ( 10.1098/rspb.2007.1762) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Timmermans MJTN, et al. 2014. Comparative genomics of the mimicry switch in Papilio dardanus. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20140465. ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.0465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang W, Westerman E, Nitzany E, Palmer S, Kronforst MR. 2017. Tracing the origin and evolution of supergene mimicry in butterflies. Nat. Commun. 8, 1-11. ( 10.1038/s41467-016-0009-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Caceres M, Ranz JM, Barbadilla A, Long M, Ruiz A. 1999. Generation of a widespread Drosophila inversion by a transposable element. Science 285, 415-418. ( 10.1126/science.285.5426.415) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gray YHM. 2000. It takes two transposons to tango: transposable-element-mediated chromosomal rearrangements. Trends Genet. 16, 461-468. ( 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02104-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Re-analyses are conducted using raw sequencing data deposited in NCBI BioProject PRJNA234541 (SRR1118145, SRR1118150, SRR1118152, SRR1111718, SRR1112070, SRR1112619), PRJDB7193 (SAMD00131361), PRJDB5519 (SAMD00074266–SAMD00074276) and PRJNA589019 (SAMN13265081–SAMN13265107, SAMN13265109–SAMN13265127).