Abstract

Fe3O4@SiO2-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane-1,8-bis (3-chloropropoxy) anthracene-9,10-dione was synthesized as a new, sustainable, and environmentally friendly adsorbent for magnetic solid-phase extraction of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions. The structure of the adsorbent was characterized by FTIR, XRD, SEM, EDX, and TEM analysis. Optimum conditions for Cu(II) adsorption were determined as adsorbent dose 0.04 g, pH 5.0, contact time 120 min, and beginning concentration of 30 mg/L in the adsorption process. The adsorption capacity for Cu(II) ions was 43.67 mg/g and the removal efficiency was 84.72 percent. The Langmuir isotherm and the pseudo-second-order model fit the experimental data better. Adsorption was a spontaneous and endothermic process based on the obtained thermodynamic properties such as ΔG°, ΔH°, and ΔS°. The results showed that the sorbent has good selectivity in the presence of competing ions. The method was determined to be accurate and effective using real water samples and CRM.

Keywords: Adsorption, Cu(II), Isotherm, Kinetic, Magnetic

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2-3-aminopropyl-trimethoxysilane-1,8-bis(3-chloropro-poxy) anthracene-9,10-dione was synthesized as a new, sustainable, and environmentally friendly adsorbent for magnetic solid-phase extraction of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions.

-

•

The results showed that the presence of competitor ions did not have a significant effect on the sorption of Cu(II) ion and the sorbent had good selectivity.

-

•

Using real water samples and CRM, the method was found to be accurate and effective.

Adsorption, Cu(II), isotherm, kinetic, magnetic.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of industry and production, heavy metals are thrown into water bodies and causing environmental water pollution to increase. Thus, the removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions has become an important field of study [1]. Heavy metals are non-biodegradable and stable [2]. Most heavy metal ions are carcinogenic or mutagenic. With heavy metals increasing concentration in the environment, they can accumulate in the human body through the food chain and threaten human health if they exceed the normal range [3]. Copper (Cu) is a necessary element in the human body and many biological systems. About 40 μg/L of copper is required for the normal metabolism of many living organisms, but higher amounts of copper cause serious deterioration in human health [4, 5]. Cu(II) can produce chronic anemia, cirrhosis, hemolysis as well as nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic side effects such as cramps, gastrointestinal diseases, vomiting, convulsions, and even death [6, 7]. Additionally, copper is a common heavy metal that is classified as a priority pollutant by the US Environmental Protection Agency [8, 9]. It is important to develop a sensitive and reliable analytical method to efficiently separate and enrich Cu(II) ions from environmental waters.

Until today, many methods such as adsorption, membrane filtration, ion exchange, chemical precipitation, and electrochemical treatment technologies have been used in this regard [10, 11, 12]. Adsorption is one of the most widely used and efficient techniques because of cheap processing costs, simplistic properties, and processes for removing lower heavy metal ion concentrations [13, 14, 15]. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) is also a method of interest for the removal of heavy metals, and magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) has been frequently used in many applications for the enrichment of heavy metal ions [16, 17, 18].

Nanocomposite materials are known as more efficient and attractive sorbents due to their multifunctionality in sample preparation techniques. Nanomaterials such as carbon-based sorbents [19, 20, 21], low-cost lignocellulosic substrates [22, 23], metal oxide composites [24, 25], and mesoporous silica [26, 27] have attracted attention to removing heavy metal ions. Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), especially with superparamagnetic properties, are frequently used in MSPE techniques for the concentration, departure, and removal of diverse analytes [28]. Magnetic nanoparticles are utilized as the extraction medium in the MSPE method, which is a modified model of the SPE method. The magnetic sorbent can be disseminated directly into the sample solution without any extra treatment, reducing sample handling processes. The contact surface between the analytes and the magnetic sorbent is particularly large because the magnetic sorbent is rapidly disseminated in solution, resulting in rapid extraction and a fast balance of mass transfer. The analyte-loaded magnetic sorbent is readily allocated from the sample solution by utilizing a magnet except for the sample solution. Because of its high, efficient, and quick extraction efficiency, MSPE is frequently regarded as an excellent sample preparation procedure. MNPs, have gotten a lot of interest in the last years because of their unique magnetic features, as well as their biocompatibility, high activity, low toxicity, high surface, simple, and cost-effective production procedure [29, 30]. Because of its chemical stability superior, ease of surface modification, and biocompatibility, silica has been recognized as an appropriate coating layer for Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles. For example, earlier research on U(VI) adsorption on SiO2@Fe3O4 magnetic composite demonstrated that the composite particles' adsorption capability is quick and strong [31]. Surface modification can be performed to increase the chemical-thermal stability, reaction activities, adsorption efficiency, selectivity and binding capacity of the analyte on the surface of nanoparticles [32, 33, 34, 35]. The PVA/Fe3O4/SiO2/APTES magnetic nanohybrid was found to be an excellent adsorbent for Th(IV) adsorption in another study [36]. In another study, Fe3O4-GO@SiO2 nanocomposite was successfully applied for the simultaneous and sensitive determination of chrome(III), cobalt(II), and copper(II) ions in environmental water samples [1].

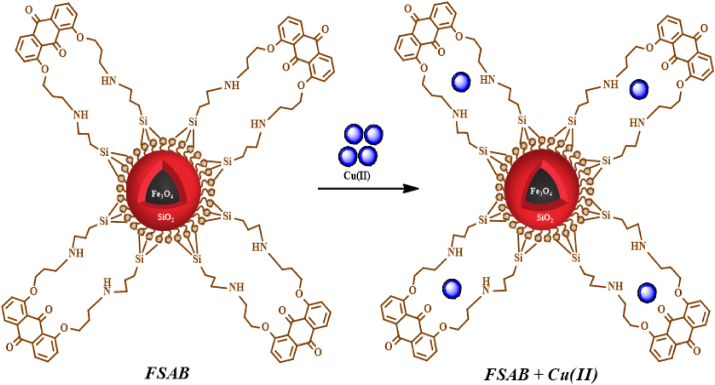

As far as we know, a new and selective adsorbent Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS-BCAD (FSAB) was used for the first time for the adsorption of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions (Figure 1). The commonly utilized co-precipitation technique was employed to prepare superparamagnetic magnetite nanoparticles (Fe3O4) in this work, and then the surface was coated with tetraethyl orthosilicate (SiO2). Modification of magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles on the surface was performed by APTMS and BCAD. The modification is aimed to increase the chemical stability, selectivity, reproducibility, extraction efficiency, and active binding sites of Cu(II) ions. The chemical and physical features of the prepared FSAB nanoparticle were determined by SEM, FT-IR, EDX, TEM, and XRD analysis. Optimum conditions were determined by examining the effects of adsorption parameters on the adsorption process. Adsorption kinetics, thermodynamics, and mechanism were analyzed. In addition, the reusability and selectivity of magnetic FSAB were also researched.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticle, and the magnetic FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and apparatus

Toluene (99.8%), iron(II) chloride tetra hydrate (FeCl2.4H2O, >99%) (3-Aminopropyl) trimethoxysilane (APTMS, 97%), ammonia (25%), methanol (≥99.9%), tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, ≥99.0%), hydrochloric acid (37%), nitric acid (≥65%) (ethanol (99%), sodium hydroxide (≥98%), iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O, 99%), and acetone (99.5%) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Molecularsieve (4 Å beads 8–12 mesh), isopropyl alcohol ((2-propanol) ≥99.7%), triethylamine (TEA), and 1,8–bis(3-chloropropoxy) anthracene-9,10-dione (BCAD) were supplied from Sigma-Aldrich. 1000 mg/L metal standard solutions in 0.5% HNO3 were purchased from Merck.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100F (JEOL), X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker-D8 Advance with Davinci), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, HITACHI (SU5000), and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR, Bruker Vertex 70 ATR-FTIR) were used to characterize the nanoparticle samples generated in each stage. The pH of the studies was adjusted using a Jenway 3010 digital pH meter. Using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry, the residue copper(II) concentrations in the solutions after adsorption were determined (ICP-OES, Agilent-720).

2.2. Preparation of FSAB nanoparticle

As in our earlier work, we synthesized superparamagnetic magnetite (Fe3O4), silica-coated Fe3O4@SiO2, and modified Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticles [37, 38]. Figure 1 depicts the possible configurations of superparamagnetic magnetite (Fe3O4), silica-coated Fe3O4@SiO2, and modified Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS. 2.0 g of modified Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticles were introduced to a 100 mL reaction container with 60 mL of thirsty toluene and sonicated for 15 min to make the magnetic FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent. After, this suspension solution was added to 1.2 g of BCAD compound and 0.6 mL of triethylamine and refluxed for 76 h with continuous stirring under N2 gas. After the reflux period, the solid nanoparticle adsorbent in the suspension mixture was separated using an externally applied magnet, washed with copious amounts of methanol-toluene, and dried at 80 °C overnight, like in our previous study [39]. The magnetic FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent likely structure is depicted in Figure 1.

2.3. Experiments on adsorption

Batch adsorption works were realized to define the efficacy of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent in removing Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions. Adsorption experiments were applied in a shaking incubator (JSR JSSI-300xx Series) at 250 rpm. For batch adsorption works, a stock solution including 100 mg/L Cu(II) was prepared and diluted into various concentrations with deionized water. 0.1 M NaOH and HCl were used to set the pH of the Cu(II) solution at the start. In all studies, the samples were separated using a magnet to separate the FSAB absorbent and the amount of Cu(II) remaining in the solution was measured by ICP-OES technique. The percent removal of Cu(II) ions by FSAB adsorbent (% Removal) and adsorption capacity (qe (mg/g)) were computed by Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively [40, 41, 42].

| (1) |

| (2) |

Here, Co (mg/L) is the beginning concentration of solution; m (g) is the weight of FSAB; Ce (mg/L) is the concentration of remaining Cu(II) ions after adsorption or at equilibrium, and V (L) is the volume of the solution.

From the adsorption experiments, the effect of the adsorbent dose was carried out by shaking various dosages of FSAB adsorbent ranging from 0.01 to 0.06 g with a 30 mg/L concentration of Cu(II) solution (50 mL) at 25 °C. The initial pH effect on adsorption was carried out by shaking Cu(II) solution of 30 mg/L concentration (50 mL) at distinct (1–7) pH values with 0.04 g FSAB at 25 °C.

Shaking at different time intervals (5–180 min), 0.04 g FSAB, 30 mg/L concentrated Cu(II) solution (50 mL) pH = 6, and at 25 °C were used to investigate the impact of contact time on adsorption. The results of this investigation were utilized to test extensively usage pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic models. Table S1 in supplementary material lists the equations and parameter constants for various kinetic models.

With varying beginning copper concentrations (10–50 mg/L) and shaking at 0.04 g of FSAB, pH = 6, and 25 °C, studies of the impact of beginning Cu(II) concentration on adsorption were carried out. The data obtained from the study were applied to the widely used Freundlich, Dubinin–Radushkevich (D-R), Langmuir and Temkin isotherm models. The equations and parameter constants of these adsorption isotherm models are shown Table S1 in supplementary material.

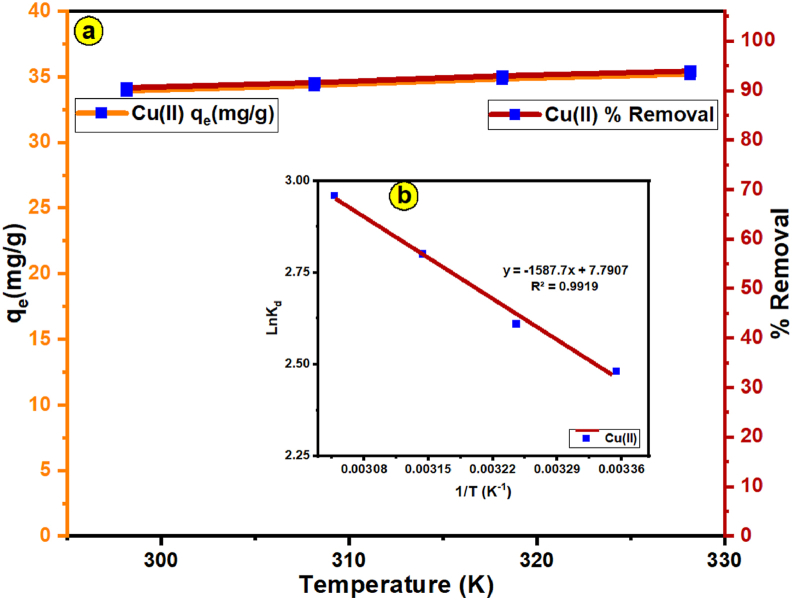

The studies of the impact of temperature on adsorption were realized at different temperatures (298–328 K) with 0.04 g of FSAB adsorbent and 30 mg/L concentration of Cu(II) solution (50 mL) by shaking at pH = 6. Thermodynamic parameters were calculated using the data obtained from this study. Equations and constants of thermodynamic parameters are given Table S1 in supplementary material.

Calibration curves were developed at 5 distinct concentrations for the sample analysis, and an external calibration method was applied. The instrumental parameters are given Table S2 in supplementary material. The analytical characterization of the technique used was carried out under optimized conditions for Cu(II) (Table S3 in supplementary material). 10 independent analyses (n = 3) of an empty metal-added solution were done for the minimum concentration grade of the analytical graph, linear ranges were utilized for calibration, and coefficients of specification (R2) were used to evaluate linearity (R2 > 0.99). The standard deviation (σ) and slope (m) of these results were used to compute the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) (LOD = 3.σ/m and LOQ = 10.σ/m).

In the selectivity studies, the distribution of Cu(II) relative to the competitor ions and the selectivity coefficients were calculated from the equilibrium binding data according to Eqs. (3) and (4) [43]. A higher selectivity coefficient indicates a better separation effect, such as increased selectivity [44]. 10.0 mL of 2.0 mg/L Cu(II) solution and each competitor ion solution were added onto the sorbent and shaken (pH 5.0). After sorption equilibrium was established, competitor ion (As, Al, B, Be, Ba, Cd, Ca, Cr, Hg, Fe, Li, K, Mn, Mg, Ni, Na, Pb, P, Se, Sc, Sr, Zn, Ti) and copper amounts in the remaining solutions were analyzed by ICP-OES.

| (3) |

| (4) |

Here, Kd is the distribution coefficient, k is the selectivity coefficient, Xn+ represents competitor ions and Mm+ is the target ion.

The performance of the proposed method has been studied using tap water, ultrapure water, and bottled drinking water samples under optimum conditions. Tap water from Karaman, Turkey, and bottled drinking water in Bursa was acidified to pH 2.0 with HNO3 immediately after sampling. It was stored in polyethylene bottles until analysis (n = 3). In addition, for the accuracy of the method, certified reference material (CRM) G3RM-1201, UME (spring water) and Cu(II) ion were analyzed (n = 3) and verified.

2.4. Desorption and reusability experiments

To evaluate the reusability potential of FSAB, consecutive adsorption-desorption cycles were performed. Cu(II) adsorption experiments on FSAB were repeated at optimum equilibrium conditions. 0.04 g of Cu(II)-loaded FSAB was shaken in the desorbing agent HNO3 (50 mL of 0.1 M) in a 100 mL erlenmeyer at 250 rpm in a shaker for 2 h at 298 K. Magnetic separation was employed to extract the FSAB adsorbent from the acidic solution, which was then completely cleaned with deionized water and reused in the next reuse-regeneration cycle. Cu(II) concentration in an acidic solution was defined using ICP-OES.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization

3.1.1. FT-IR analysis

Figure 2 shows the results of FT-IR spectra to verify the structural composition of the BCAD compound and the nanoparticle samples obtained. In the FT-IR spectrum of pure Fe3O4 obtained (Figure 2a), the peak at wavenumber 540 cm−1 indicates typical Fe–O stretching vibrations [45]. The peak at 1636 cm−1 represents water adsorbed on the surface of Fe3O4 nanoparticle, and the wide-stretching vibration peak seen at 3405 cm−1 represents the stretching vibrations of –OH on the surface of Fe3O4 nanoparticle [46, 47]. In the FT-IR spectrum of SiO2@Fe3O4 particles formed after the surface of the Fe3O4 nanoparticle is coated with the SiO2 shell (Figure 2b), new peaks appeared at 442, 797, 952, and 1084 cm−1. The bending vibration of O–Si–O, symmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si, the telescoping vibration of Si–OH [48], and asymmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si, respectively, are represented by these peaks [46, 49]. These findings reveal that silica (SiO2) was successfully coated onto the surface of Fe3O4 nanoparticles.

Figure 2.

FT-IR spectra of (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4@SiO2, (c) Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticles, (d) FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent and (e) BCAD compound.

The absorption peak detected at 2926 cm−1 in the FT-IR spectra of Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS (Figure 2c) expresses the C–H stretching vibrations of the propyl group, indicating the existence of the APTMS linker [50]. Also, the absorption peaks appearing at 1481 cm−1 and 1572 cm−1 show twist and tensile vibrations of amino groups, respectively [51]. The absorption peak appearing at 1328 cm−1 represents a Si–C group in the magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticle structure. These findings show that the Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticle surface has been changed by the APTMS chemical. In the FT-IR spectrum of the magnetic FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent (Figure 2d), the peak appearing at 1291 cm−1 represents the tensile vibration of the C–N bond (amide) after BCAD bonding to the Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS surface, and the peak at 1649 cm−1 shows the C=O groups in BCAD. The absorption peaks at 1467 cm−1 and 1601 cm−1 are observed to be associated with aromatic C=C bending and aromatic C=C stretching mode, respectively. These findings, as well as the novel peaks and changes in the spectrum in Figure 2d, show that the magnetic FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent was successfully synthesized.

3.1.2. TEM analysis

Figure 3 indicates the TEM images of produced Fe3O4, Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS, and FSAB nanoparticles, as well as the diameter distribution analysis of nanoparticles. As seen in Figure 3a, Fe3O4 particles are approximately the same size, spherically formed, and homogeneously dispersed. Fe3O4 nanoparticles had sizes ranging from 6 to 18 nm, with an average diameter of 9 nm, in accordance with the particle size distribution analysis result in Figure 3a (inner picture). As seen in the Fe3O4@SiO2 TEM image (Figure 3b), which is formed after the surface of Fe3O4 nanoparticles is coated with silica (SiO2), it is seen that the surface of Fe3O4 nanoparticles is covered with a thin flat layer (amorphous structure of SiO2) [52]. The main goal of forming the outer silica shell is to prevent Fe3O4 particles from corroding. As shown in Figure 3b, basically a core-shell structure (dark core for Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles) was obtained. Fe3O4@SiO2 particles had sizes ranging from 8 to 20 nm, with a mean diameter of 11 nm, according to the results in Figure 3b (interior view). According to the results of the TEM image and particle size distribution analysis of Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS in Figure 3c, it was determined that its particles were between 8 and 20 nm and its average diameter was 11.5 nm. According to the TEM image (Figure 3d) and particle size distribution analysis result (Figure 3d inner image) of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent formed after the BCAD compound immobilization on the surface of Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticles, its particles were determined to be between 8 and 21 nm and the average diameter was 13 nm. The monodispersed magnetic nanoparticles have a consistent shape and a nearly spherical structure without any agglomeration, according to TEM measurements. These results, confirm that the designed FSAB nanoparticle adsorbents were successfully synthesized.

Figure 3.

TEM images of (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4@SiO2, (c) Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS and (d) FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

3.1.3. XRD analysis

XRD analysis was made to specify the crystallographic properties of the synthesized FSAB nanoparticles, Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS, Fe3O4@SiO2, Fe3O4, and the XRD patterns are shown in Figure 4a-d.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4@SiO2, (c) Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS and (d) FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

In the XRD model of Fe3O4 nanoparticles in Figure 4a, the peaks at 29.98 (220), 35.43 (311), 43.44 (400), 53.33 (422), 57.12 (511), and 62.69 (440) degrees correspond to the standard data of the Fe3O4 diffraction peak (JCPDS No. 75-0449) [53, 54, 55, 56, 57]. In the XRD model of Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles (Fig. 4b), a wide peak in the range of 2θ = 15°–30° was formed, confirming the formation of an amorphous silica shell (SiO2) surrounding Fe3O4 nanoparticles [58]. After coating Fe3O4 nanoparticles with silica (Figure 4b), modification of Fe3O4@SiO2 with APTMS functional group (Figure 4c), and immobilization of Fe3O4@SiO2- APTMS with BCAD compound (Figure 4d), the crystal structure of Fe3O4 nanoparticle appears to be preserved. It is seen that there is only an increase-decrease or expansion-contraction in the intensity of these diffraction peaks. The XRD data show that the intended FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent was successfully manufactured. According to the Debye–Scherrer equation [59, 60, 61], the average particle size of the prepared nanoparticle materials was 13.41, 12.86, 12.23 and 9.12 nm for FSAB, Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS, Fe3O4@SiO2, and Fe3O4 respectively.

3.1.4. SEM and EDX analysis

SEM and EDX results of Fe3O4, silica-coated Fe3O4@SiO2, modified Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS nanoparticle, and FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent are shown in Fig. 5a-d. As illustrated in Figure 5a, the differences between the SEM and EDX results of the nanoparticles prepared in each step are visible. The morphology of the produced nanoparticle was evaluated and its chemical compound was determined using SEM and EDX analyses. The nanostructure has iron (Fe), carbon (C), oxygen (O), silicon (Si), and nitrogen (N) according to EDX analysis. Figure 5a shows that the Fe3O4 particles were all monodispersive and spherical. A clear gray silica sheet on the Fe3O4 surface is obviously evident for Fe3O4@SiO2 (Figure 5b). After coating with the APTMS complex, the microspheres bond together, and its surface becomes rougher than the Fe3O4@SiO2 surface (Figure 5c). After immobilization of BCAD complex on modified Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS, particle size changed (Figure 5d). These findings show that the planned FSAB adsorbent nanoparticles were successfully manufactured.

Figure 5.

(a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4@SiO2, (c) Fe3O4@SiO2-APTMS, and (d) FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent SEM images and EDX data.

3.2. Adsorption studies

3.2.1. The effect of adsorbent dosage

Before deciding on the amount of adsorbent to utilize, we examined the impact of adsorbent quantity on the adsorption removal rate and capacity. The results are given in Figure 6. As shown in Figure 6, as the adsorbent dose increases, the adsorption capacity falls. On the other hand, increasing the dose of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent results in an increase in adsorption effectiveness up to a certain point. Therefore, active sites develop as the number increases [62]. It was determined that low adsorbent dosage and high adsorption capacity for the removal of toxic copper ions from aqueous samples are appropriate in order to usage in the adsorption operation of FSAB. When the amount of adsorbent is 0.04 g, more than 82.67% of Cu(II) is removed, together with the impact of Cu(II) concentration on adsorption capacity. Therefore, other adsorption studies were realized by taking 0.04 g as a dose and it is lower than many studies in the literature [63, 64, 65].

Figure 6.

Effects of adsorbent dose on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

3.2.2. The effect of pH on Cu(II) adsorption

The pH of the solution can change the chemical state of the active groups in the adsorbent, the charge distribution on the adsorbent surface, and the presence of metal ions in the solution, all of which can affect the adsorbent affinity [66]. Figure 7 shows the impact of solution pH on Cu(II) adsorption on FSAB. The adsorption efficiency and capacity were observed to have an increasing trend from pH 1 to 5 and reduced from 5 to 7 as indicated in Figure 7. The chemical environment has a significant impact on the existence of amine groups and O-including functional groups on the adsorbent surface, as well as the acidity and alkalinity of these groups [67]. When Cu(II) is adsorbed on FSAB, it can form complexes with oxygen-containing functional groups and surface structural amine groups. The existence of free amine groups in the solution improves the adsorption between metal ions and protons as the pH rises, lowering electrostatic repulsion. The ability of FSAB to adsorb Cu(II) ions has been substantially increased [68]. As a result, for the other adsorption experiments, the optimal pH value (5.0) was chosen. This result is in agreement with previous studies [11, 64, 69].

Figure 7.

Effect of pH on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

3.2.3. The effect of contact time

The impact of contact duration on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent is shown in Figure 8. The adsorption capacity and removal efficiency increase over the first 120 min, as shown in Figure 8. After this (120 min) time, it is seen that the adsorption curve reaches equilibrium. Because the active sites are bigger and more scattered in the early phases of adsorption, this result shows that toxic metal ion adsorption is faster. This is in line with our previous work and literature [25, 70, 71]. As a result, the contact time of 120 min was chosen for other adsorption experiments.

Figure 8.

Effect of contact time on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

3.2.4. Influence of initial Cu(II) concentration

Figure 9 shows the influence of different beginning Cu(II) concentrations on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent. As shown in Figure 9, Cu(II) removal effectiveness declined as the original concentration increased. However, the adsorption capability when the starting concentration of the heavy metal utilized was increased. As shown in Figure 9, we may conclude that 30 mg/L is the optimal concentration for maximal removal efficiency and the best adsorption capacity and it is lower than many studies in the literature [11, 63, 69].

Figure 9.

The influence of initial Cu(II) concentration on copper adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

3.3. Adsorption kinetics

The kinetic study is critical for determining the adsorbate absorption rate in the adsorption operation and controlling the total process time [72]. The pseudo-second-order (PSO) and pseudo-first-order (PFO) equations Table S1 in supplementary material were applied to investigate the behavior of Cu(II) adsorption kinetics for FSAB. The kinetic models' graphs are shown in Fig. 10a-b, and the computed kinetic parameters are included in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, it is clearly observed that the correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.998) of the PSO kinetic model is higher than that of the PFO kinetic model (R2 = 0.9618). Also, the equilibrium adsorption capacity calculated from the PSO equation (qe (cal) = 38.760 mg/g) is more approximate to the experimental data (qe (exp) = 34.620 mg/g), indicating that the PSO model is more apt to predict the kinetic properties of Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent. The applicability of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model reveals that Cu(II) ion adsorption on the FSAB is dependent on chemical interactions such as ionic and chemical bonds involving electron exchange among the adsorbent and the adsorbate. Metal ions chemically bond to the adsorbent surface and seek out places with the highest number of coordination [73].

Figure 10.

Plots of Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent using (a) pseudo-first-order (PFO) and (b) pseudo-second-order (PSO) kinetic models.

Table 1.

Parameter results of kinetic adsorption models.

| qe(exp) (mg/g) | Pseudo-first-order (PFO) |

Pseudo-second-order (PSO) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1 min−1 |

qe(cal) (mg/g) |

R2 | k2 g/(mg min) |

qe(cal) (mg/g) |

R2 | |

| 34.620 | 0.021 | 26.194 | 0.9618 | 0.0011 | 38.760 | 0.998 |

3.4. Adsorption isotherm

Experimental isotherm data were applied to the isotherm model equations Table S1 in supplementary material and the acquired adsorption isotherm curves and isotherm parameter constant values are shown Fig. S1 in supplementary material and Table 2, respectively. When the R2 values of the Langmuir isotherm model and the other isotherm models are compared in Table 2, the R2 value of the Langmuir isotherm model is greater than the other isotherm models, showing that the Langmuir isotherm model is more compatible with the other models. A dimensionless separation factor (RL) is a vital feature of the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model. RL, defines the isotherm type to be either unfavorable (RL > 1), irreversible (RL0), linear (RL = 1) or favorable (0 < RL< 1) [74,75]. In the calculations, RL values (0.073–0.016) were found in the range of 0–1, and this result shows that it fits the Langmuir isotherm model. When the results were examined, it was understood that the adsorption process of Cu(II) ions by FSAB was monolayer adsorption [76]. According to the Langmuir isotherm model, the maximum adsorption capacity (qm) is 43.67 mg/g. E (the adsorption energy) calculated from the Dubinin-Radushkevich model is 3.163 kJ/mol. The kinetic research was utilized to evaluate the adsorbate absorption rate in the adsorption operation, control the overall process time, and determine if chemisorption is the rate-limiting phase in the adsorption process. As a result, it was plausible to conclude that chemisorption, which contained valency strengths through the exchange or sharing of electrons among the metal ions and the adsorbent, was the rate-limiting phase during the adsorption of Cu(II) ions onto FSAB. Moreover, the mean free energy (E) for Cu(II) ions was less than 8 kJ/mol (based on the D-R isotherm) [77, 78], showing that physical adsorption was also engaged in the adsorption operation.

Table 2.

Parameter results of the four adsorption isotherms.

| Temkin isotherm model | Freundlich isotherm model | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| bT (J/mol) | 364.0 | n | 3.610 |

| AT (L/g) | 34.232 | KF (mg/g) | 3.795 |

| R2 |

0.9855 |

R2 |

0.9519 |

|

Langmuir isotherm model |

Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherm model |

||

| R2 | 0.9984 | qm (mg/g) | 35.538 |

| qm (mg/g) | 43.67 | R2 | 0.8873 |

| RL | 0.073–0.016 | E (kJ/mol) | 3.163 |

| KL (L/mg) | 1.251 | β (mol2/kJ2) | -5E-08 |

3.5. Investigation of adsorption capacities of different adsorbents

The FSAB adsorbent's highest adsorption capacity for Cu(II) removal was compared to that of other adsorbents in the literature (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, When compared to other adsorbents, the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent has a high adsorption capacity, meaning that it has a significant adsorption ability against Cu(II) ions.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Langmuir adsorption capacity of magnetic or different adsorbents for Cu(II) removal.

| Adsorbent | qm (mg/g) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 nanomaterial | 11.5 | [79] |

| Magnetic nanoparticles with diethylenetriamine functionalization | 12.4 | [80] |

| Sulfhydryl functionalized hydrogel by magnetism | 15.6 | [81] |

| Fe3O4/kaolin clay | 16.5 | [82] |

| Bent-2.0/Fe3O4 | 19.6 | [83] |

| Diatomite from Algeria | 20.3 | [84] |

| Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles linked to chitosan | 21.5 | [85] |

| Amino-functionalized magnetic nano sorbent | 25.8 | [86] |

| Immobilized microorganisms on polyurethane (IPU) foam | 28.7 | [87] |

| Chitosan/SiO2/Fe3O4 | 31.7 | [88] |

| Xanthate-modified magnetic chitosan | 34.5 | [89] |

| Magnetic chitosan nanoparticles | 35.5 | [90] |

| Poly (methyl methacrylate)-grafted alginate/Fe3O4 nanocomposite | 35.7 | [91] |

| LDH-Cl | 36.0 | [92] |

| Treating Fe3O4 nanoparticles with gum arabic | 38.5 | [93] |

| Modified activated carbon | 38.1 | [94] |

| Baker's yeast biomass/Fe3O4 | 41.0 | [95] |

| A-LDH | 42.0 | [96] |

| Nano chitosan/sodium alginate/microcrystalline cellulose beads | 43.3 | [97] |

| FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent | 43.67 | This work |

3.6. Effect of temperature and thermodynamic studies

The influence of temperature (298–328 K) on Cu(II) adsorption by FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent was researched with the findings seen in Figure 11a. As indicated in Figure 11a, the adsorption efficiency and capacity of Cu(II) ions on FSAB increased slightly as the temperature increased from 298 to 328 K. The stronger interplay among the Cu(II) ion and the active sites of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent is responsible for the increase in Cu(II) adsorption. As a result, it shows that the adsorption operation of Cu(II) ions on FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent is endothermic in nature. Thermodynamic parameters like a change in enthalpy (ΔHo), entropy (ΔSo) and free energy (ΔGo) were defined using the thermodynamic equations presented in Table S1 in supplementary material to describe the thermodynamic behavior of Cu(II) adsorption onto the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent. The Van't Hoff graph obtained from this equation is given in Figure 11b and the obtained thermodynamic parameter values are dedicated in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, the values (−6.11, −6.76, −7.41, and −8.05 kJ mol−1) of the calculated ΔG° are negative, showing the spontaneous nature of Cu(II) adsorption on FSAB [98]. In addition, since the ΔGo values obtained in this study are between −20 and 0 kJ mol−1 [99], we can say that Cu(II) adsorption on FSAB occurs by a physisorption mechanism. On the other hand, as shown in Table 4, the values of ΔS° and ΔH° are positive, showing that the adsorption reaction is endothermic and randomness improves at the solid-solution interface in the course of the Cu(II) adsorption by FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent, respectively.

Figure 11.

(a) Impact of temperature on Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB,(b) The Van't Hoff plot for Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameter values for Cu(II) adsorption by the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent.

| Temperature (K) | ΔGo (kJ mol−1) | ΔSo (J K−1 mol−1) | ΔHo (kJ mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | −6.11 | 64.77 | 13.20 |

| 308 | −6.76 | ||

| 318 | −7.41 | ||

| 328 | −8.05 |

3.7. Adsorption mechanism

Magnetic nanoparticles of Fe3O4 provide excellent magnetic separation carriers and are frequently employed to improve separation efficiency [100]. Especially in acidic solutions, Fe3O4 nanoparticles have easy oxidation/dissolution [101]. To solve this problem, SiO2 provided a suitable shell structure [102]. SiO2 is known as an ideal coating layer for MNPs with its chemical stability, easy surface modification, and good biocompatibility [11]. 1,8-bis (3-chloropropoxy) anthracene-9,10-dione (BCAD) and 3–aminopropyltrimethoxysilane (APTMS) was used to functionalize the Fe3O4@SiO2 MNPs. The modification of the magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles with APTMS and BCAD on the surface increased the density of the functional groups. Thus, it is thought that Cu(II) ions greatly increase the active binding sites [39]. Cu(II) or other metal ions are well known to be adsorbed onto adsorbent via coordination and electrostatic attraction [103]. The potential of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent used in this study plays an important role in Cu(II) adsorption. As seen in Figure 12, Cu(II) adsorption by FSAB is due to the coordination between -NH- (amine) groups and divalent Cu(II) ions on the FSAB surface. The donor functional groups on FSAB (N-atoms), are generally connected to the Cu(II) ions, resulting in a donor-acceptor interaction between Cu(II) and the FSAB [104, 105]. The other way of binding can be said that its adsorption takes place because of the electrostatic attraction among positive Cu(II) ions and negative FSAB.

Figure 12.

The probable reaction mechanism underlying the adsorption process.

3.8. Regeneration and reusability of the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent

The ability of an effective adsorbent to regenerate is a key aspect in determining its economic viability. Figure 13 depicts the regeneration and recycling characteristics of FSAB as measured across four regeneration cycles. The adsorption capacity of FSAB decreased only a little after each adsorption–regeneration loop, and after four cycles, it was >82 percent of its original adsorption capacity. It shows that the FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent is highly durable during the repeated regeneration process and is promising for Cu(II) adsorption from aqueous solutions.

Figure 13.

The FSAB nanoparticle adsorbent's adsorption efficiency and capacity for Cu(II) after four successive adsorption–regeneration cycles.

3.9. Selectivity study

The presence of different metal ions in actual contaminated water might poison the adsorbent. Therefore, selective pollutant removal will be very important for practical applications [106]. The effect of the presence of different metal ions on Cu(II) removal with FSAB was investigated.

The sorption selectivity for Cu(II) was investigated against various ions (As, Al, B, Be, Ba, Cd, Ca, Cr, Hg, Fe, Li, K, Mn, Mg, Ni, Na, Pb, P, Se, Sc, Sr, Zn, and Ti). 10.0 mL of 2.0 mg/L Cu(II) solution and each competitor ion solution were added onto the sorbent and shaken (pH 5.0). Competitor ion and copper concentrations in solutions were analyzed by ICP-OES after sorption equilibrium was established. Then, Cu(II) and the sorption percentage of these ions, selectivity coefficients (k), and distribution coefficients (Kd) were calculated according to Eqs. (3) and (4). These coefficients are frequently used to assess a sorbent's ability to bind sorbates [43].

The decreasing order of selectivity for Cu(II) ions is Al > B > As > Fe > Hg > Pb > Cr > Be > Se > Mg > Ni > Na > Sr > Zn > Mn > Ti > Ba, Ca, Cd, Li, P, Sc (Table 5). In the presence of competitor ions, FSAB preferentially removed Cu(II) ions with ≥99% removal rate. Overall, in agreement with previous literature reports, the FSAB nanomaterial showed good selectivity towards Cu(II) adsorption [106, 107]. The results show that the presence of the corresponding competing ions under the reported circumstances had no important impact on the sorption of Cu(II) ions. The good selectivity of the Cu ion is due to the good affinity of the amine groups for Cu(II) ions and the ability to form stable metal chelates [106]. As a result, it was determined that FSAB has good selectivity for the adsorption of Cu(II) ions.

Table 5.

Percent sorption, Kd and k values of Cu(II) with respect to competitor ions. (0.04 g sorbent, pH of 5.0, 10.0 mL solution volume, 120.0 min contact time, n = 3).

| Ion∗ | Sorption (%) | Kd (mL/g) | k |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | 99 | 24.75 | - |

| Al | 87 | 21.75 | 31.11 |

| As | 77 | 19.25 | 35.15 |

| B | 85 | 21.25 | 31.84 |

| Ba | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Be | 51 | 12.75 | 94.80 |

| Ca | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Cd | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Cr | 65 | 16.25 | 45.66 |

| Fe | 72 | 18.0 | 37.60 |

| Hg | 69 | 17.25 | 43.01 |

| Li | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Mg | 39 | 9.75 | 154.0 |

| Mn | 14 | 3.50 | 653.7 |

| Na | 19 | 4.75 | 481.6 |

| Ni | 35 | 8.75 | 167.0 |

| P | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Pb | 68 | 17.0 | 43.64 |

| Sc | 1.0 | 0.25 | 8855 |

| Se | 45 | 11.25 | 112.1 |

| Sr | 17 | 4.25 | 538.0 |

| Ti | 11 | 2.75 | 832.0 |

| Zn | 16 | 4.0 | 572.0 |

Co = 125.0 μg/L for Cu(II), B, Ba, Cr, Cd, Fe, Li, Ti, Zn, 1.25 mg/L for Al, As, Ca, Na, P, Pb, Se, 31.25 μg/L for Be, Mg, Mn, Sc, Sr, and 62.5 μg/L for Hg, Ni ions.

3.10. Real sample analysis

Because of the variability of the adsorbent, the complexity of the actual samples, and cleaning effectiveness, heavy metals in laboratory-created standards may be distinct from environmental water samples. For this reason, it is important to research the effectiveness of the adsorbent below real environmental examples [108]. Tap water, ultrapure water, and bottled drinking water were used to test the feasibility of the proposed sorbent. The chemical and physical properties of these samples are given Table S4 in supplementary material. Analysis of real samples was evaluated by adding 5.0, 10.0, and 50.0 μg/L Cu(II) at optimum conditions (120 min contact time, pH of 5, 0.04 g adsorbent dose, 50 mL sample volume). Blind samples were equipped in a similar way and analyzed by ICP-OES and it was determined that the results were below the detection limit. As can be seen from Table 6, FSAB was determined to have a good affinity for Cu(II) removal with absorption efficiencies greater than 97.1%. It is clear from the results that the developed method is appropriate for the removal of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions. In addition, CRM-UME G3RM-1201 (spring water) was used and the accuracy of the proposed technique was confirmed by identifying target metal ions. The measured values were found to be in good agreement with the certified values and the analytical results are seen in Table 6.

Table 6.

Removal of Cu(II) by FSAB using real water samples (50 mL solution volume, pH of 5.0, 120 min contact time, 0.04 g sorbent) and analytical results of CRM (n = 3).

| Sample | Cu(II) Spike (μg/L) | Removal % |

|---|---|---|

| Tap water | 1 | 98.3 ± 3 |

| 50 | 97.1 ± 1 | |

| 100 | 97.2 ± 2 | |

| Ultrapure water | 1 | 99.3 ± 2 |

| 50 | 99.2 ± 4 | |

| 100 | 99.5 ± 2 | |

| Bottled drinking water | 1 | 97.5 ± 1 |

| 50 | 97.1 ± 3 | |

| 100 |

97.7 ± 2 |

|

|

Elements |

UME G3RM-1201 Found (μg/L) |

Certified(μg/L) |

| Cu(II) | 83.25 ± 0.97 | 83.1 ± 2.6 |

4. Conclusion

As a result of the experimental studies, FSAB nanoparticle adsorbents used in the batch adsorption of Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions were successfully prepared. Under optimum conditions, the removal efficiency (R) was determined as 84.72% and the adsorption capacity (qe) was 43.67 mg/g. The pseudo-second-order model may successfully define the adsorption kinetics. The Langmuir model best explained the equilibrium data. Thermodynamic studies indicate that the adsorption is endothermic, spontaneous and the adsorbent has a high affinity for Cu(II) ions. The sorption selectivity for Cu(II) has been studied against ions such as As, Al, B, Ba, Be, Cd, Ca, Cr, Hg, Fe, Li, Mn, K, Mg, Ni, Na, Pb, P, Se, Sc, Sr, Zn, and Ti. FSAB has a high sorption percentage for Cu(II)) ions selectively and effectively removed. Also, after five continuous cycles, the FSAB magnetic nanoparticle showed an acceptable decrease in removal efficiency. FSAB showed that the method for Cu(II) ions performed under optimum conditions in ultrapure, tap, and bottled drinking water samples has high accuracy, selectivity, and easy applicability with its high adsorption capacity. In addition, since the synthesized magnetic nanoparticle is a recyclable, environmentally friendly, and non-toxic adsorbent, it is recommended to be used to remove various pollutants such as heavy metals and pesticides from the environment.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Ali Bilgiç, Hacer Sibel Karapınar: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the management of the Department of Chemistry and Scientific and Technological Research & Application Center of Karamanoglu Mehmetbey University for providing the necessary facilities for carrying out this work.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Suo L., Dong X., Gao X., Xu J., Huang Z., Ye J., Lu X., Zhao L. Silica-coated magnetic graphene oxide nanocomposite based magnetic solid phase extraction of trace amounts of heavy metals in water samples prior to determination by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Microc. J. 2019;149 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su S., Chen B., He M., Hu B. Graphene oxide–silica composite coating hollow fiber solid phase microextraction online coupled with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry for the determination of trace heavy metals in environmental water samples. Talanta. 2014;123:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2014.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srivastava N., Majumder C. Novel biofiltration methods for the treatment of heavy metals from industrial wastewater. J. Hazard Mater. 2008;151:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.09.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahaghin Z., Mousavi H.Z., Boutorabi L. Application of magnetic ion-imprinted polymer as a new environmentally-friendly nonocomposite for a selective adsorption of the trace level of Cu (II) from aqueous solution and different samples. J. Mol. Liq. 2017;243:380–386. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabrizi A.B. Development of a cloud point extraction-spectrofluorimetric method for trace copper (II) determination in water samples and parenteral solutions. J. Hazard Mater. 2007;139(2):260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Türkdoğan M.K., Karapinar H.S., Kilicel F. Serum trace element levels of gastrointestinal cancer patients in an endemic upper gastrointestinal cancer region. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2022;72 doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2022.126978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngah W.W., Hanafiah M. Adsorption of copper on rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) leaf powder: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. Biochem. Eng. J. 2008;39(3):521–530. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peng H., Gao P., Chu G., Pan B., Peng J., Xing B. Enhanced adsorption of Cu (II) and Cd (II) by phosphoric acid-modified biochars. Environ. Pollut. 2017;229:846–853. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta M., Gupta H., Kharat D. Adsorption of Cu (II) by low cost adsorbents and the cost analysis. Environ. Technol. Innovat. 2018;10:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghorbani F., Younesi H., Ghasempouri S.M., Zinatizadeh A.A., Amini M., Daneshi A. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of cadmium biosorption in an aqueous solution by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chem. Eng. J. 2008;145:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanati A.M., Kamari S., Ghorbani F. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of cadmium adsorption from aqueous solutions by Fe3O4@ SiO2@ APTMS core–shell magnetic nanohybrid. Surface. Interfac. 2019;17 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harinath Y., Reddy D.H.K., Sharma L.S., Seshaiah K. Development of hyperbranched polymer encapsulated magnetic adsorbent (Fe3O4@ SiO2–NH2-PAA) and its application for decontamination of heavy metal ions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017;5(5):4994–5001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie Y., Yuan X., Wu Z., Zeng G., Jiang L., Peng X., Li H. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of Mg/Fe layered double hydroxide with Fe3O4-carbon spheres on the removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;536:440–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zubair M., Daud M., McKay G., Shehzad F., Al-Harthi M.A. Recent progress in layered double hydroxides (LDH)-containing hybrids as adsorbents for water remediation. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017;143:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li G., Zhang J., Li Y., Liu J., Yan Z. Adsorption characteristics of Pb (II), Cd (II) and Cu (II) on carbon nanotube-hydroxyapatite. Environ. Technol. 2021;42:1560–1581. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2019.1674385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilar-Arteaga K., Rodriguez J., Barrado E. Magnetic solids in analytical chemistry: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2010;674(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pyrzynska K., Kubiak A., Wysocka I. Application of solid phase extraction procedures for rare earth elements determination in environmental samples. Talanta. 2016;154:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He M., Huang L., Zhao B., Chen B., Hu B. Advanced functional materials in solid phase extraction for ICP-MS determination of trace elements and their species-a review. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;973:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kettum W., Tran T.T.V., Kongparakul S., Reubroycharoen P., Guan G., Chanlek N., Samart C. Heavy metal sequestration with a boronic acid-functionalized carbon-based adsorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018;6:1147–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashemi B., Rezania S. Carbon-based sorbents and their nanocomposites for the enrichment of heavy metal ions: a review. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3668-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kılıçel F., Karapınar H.S. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon produced from eriobotrya japonica seed by chemical activation with ZnCl2. Asian J. Chem. 2018;30:1823–1828. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vintila T., Negrea A., Barbu H., Sumalan R., Kovacs K. Metal distribution in the process of lignocellulosic ethanol production from heavy metal contaminated sorghum biomass. J. Chem. Technol. Biot. 2016;91:1607–1614. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakur V., Sharma E., Guleria A., Sangar S., Singh K. Modification and management of lignocellulosic waste as an ecofriendly biosorbent for the application of heavy metal ions sorption. Mater. Today Proc. 2020;32:608–619. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H., Gao B., Wang S., Fang J., Xue Y., Yang K. Removal of Pb (II), Cu (II), and Cd (II) from aqueous solutions by biochar derived from KMnO4 treated hickory wood. J. Bior. Tec. 2015;197:356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karapinar H.S., Kilicel F., Ozel F., Sarilmaz A. Fast and effective removal of Pb (II), Cu (II) and Ni (II) ions from aqueous solutions with TiO2 nanofibers: synthesis, adsorption-desorption process and kinetic studies. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta R., Gupta S.K., Pathak D.D. Selective adsorption of toxic heavy metal ions using guanine-functionalized mesoporous silica [SBA-16-g] from aqueous solution. J. Micro. Meso. 2019;288 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vojoudi H., Badiei A., Bahar S., Ziarani G.M., Faridbod F., Ganjali M.R. A new nano-sorbent for fast and efficient removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions based on modification of magnetic mesoporous silica nanospheres. J. Magn. Magn Mater. 2017;441:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L., Qiu H., Liang C., Song P., Han Y., Han Y., Gu J., Kong J., Pan D., Guo Z. Electromagnetic interference shielding MWCNT-Fe3O4@ Ag/epoxy nanocomposites with satisfactory thermal conductivity and high thermal stability. Carbon. 2019;141:506–514. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang T., Zheng L., Liu Y., Tang W., Fang T., Xing B. A novel ternary magnetic Fe3O4/g-C3N4/Carbon layer composite for efficient removal of Cr (VI): a combined approach using both batch experiments and theoretical calculation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akman E. Enhanced photovoltaic performance and stability of dye-sensitized solar cells by utilizing manganese-doped ZnO photoanode with europium compact layer. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;317 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan F.-L., Qin Z., Bai J., Rong W.-D., Fan F.-Y., Tian W., Wu X.-L., Wang Y., Zhao L. Rapid removal of uranium from aqueous solutions using magnetic Fe3O4@ SiO2 composite particles. J. Environ. Radioact. 2012;106:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boruah P.K., Borah D.J., Handique J., Sharma P., Sengupta P., Das M.R. Facile synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4 nanopowder and Fe3O4/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for methyl blue adsorption: a comparative study. J. Environ. Chem.l Eng. 2015;3(3):1974–1985. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alothman Z.A., Apblett A.W. Metal ion adsorption using polyamine-functionalized mesoporous materials prepared from bromopropyl-functionalized mesoporous silica. J. Hazard Mater. 2010;182(1-3):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J.-M., Zhai S.-R., Zhai B., An Q.-D., Tian G. Crucial factors affecting the physicochemical properties of sol–gel produced Fe3O4@ SiO2–NH2 core–shell nanomaterials. J. Sol. Gel Sci. Technol. 2012;64(2):347–357. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akman E., Karapinar H.S. Electrochemically stable, cost-effective and facile produced selenium@ activated carbon composite counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Sol. Energy. 2022;234:368–376. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirzabe G.H., Keshtkar A.R. Application of response surface methodology for thorium adsorption on PVA/Fe3O4/SiO2/APTES nanohybrid adsorbent. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;26:277–285. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bilgic A. Cimen, Synthesis, characterisation, adsorption studies and comparison of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) with three different amine groups functionalised with BODIPY for the removal of Cr (VI) metal ions from aqueous solutions. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilgiç A., Çimen A. A highly sensitive and selective ON-OFF fluorescent sensor based on functionalized magnetite nanoparticles for detection of Cr (VI) metal ions in the aqueous medium. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;312 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karapınar H.S., Bilgiç A. A new magnetic Fe3O4@ SiO2@ TiO2-APTMS-CPA adsorbent for simple, fast and effective extraction of aflatoxins from some nuts. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022;105 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Çimen A., Torun M., Bilgiç A. Immobilization of 4-amino-2-hydroxyacetophenone onto silica gel surface and sorption studies of Cu (II), Ni (II), and Co (II) ions. Desalination Water Treat. 2015;53:2106–2116. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang N., Yang D., Wang X., Yu S., Wang H., Wen T., Song G., Yu Z., Wang X. Highly efficient Pb (II) and Cu (II) removal using hollow Fe 3 O 4@ PDA nanoparticles with excellent application capability and reusability. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018;5:2174–2182. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karapınar H.S. Adsorption performance of activated carbon synthesis by ZnCl2, KOH, H3PO4 with different activation temperatures from mixed fruit seeds. Environ. Technol. 2022;43:1417–1435. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2021.1968507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yayayürük A.E., Yayayürük O. Facile synthesis of magnetic iron oxide coated Amberlite XAD-7HP particles for the removal of Cr (III) from aqueous solutions: sorption, equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019;7 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma L., Wang Q., Islam S.M., Liu Y., Ma S., Kanatzidis M.G. Highly selective and efficient removal of heavy metals by layered double hydroxide intercalated with the MoS42–ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138(8):2858–2866. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karimi B., Ghaffari B., Vali H. Synergistic catalysis within core-shell Fe3O4@ SiO2 functionalized with triethylene glycol (TEG)-imidazolium ionic liquid and tetramethylpiperidine N-oxyl (TEMPO) boosting selective aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021;589:474–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.12.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu L., Su G., Liu X., Dong W., Niu M., Kuang Q., Tang A., Xue J. Fabrication of magnetic core–shell Fe3O4@ SiO2@ Bi2O2CO3–sepiolite microspheres for the high-efficiency visible light catalytic degradation of antibiotic wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innovat. 2021;22 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L., Zhao L., Liu J., Yang Z., Su G., Song H., Xue J., Tang A. Preparation of magnetic Fe3O4@ SiO2@ CaSiO3 composite for removal of Ag+ from aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;299 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miao J., Zhao X., Zhang Y.-X., Liu Z.-H. Feasible synthesis of hierarchical porous MgAl-borate LDHs functionalized Fe3O4@ SiO2 magnetic microspheres with excellent adsorption performance toward Congo red and Cr (VI) pollutants. J. Alloys Compd. 2021;861 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao L., Liu H., Wang F., Zeng L. Design of yolk–shell Fe3O4@PMAA composite microspheres for adsorption of metal ions and pH-controlled drug delivery. J. Mater. Chem. 2014;2:7065–7074. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheykhan M., Yahyazadeh A., Ramezani L. A novel cooperative Lewis acid/Brønsted base catalyst Fe3O4@ SiO2-APTMS-Fe (OH) 2: an efficient catalyst for the Biginelli reaction. Mol. Catal. 2017;435:166–173. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L., Hu S., Sun H., Guo H., Zhu H., Liu M., Sun H. Malachite green adsorption onto Fe 3 O 4@ SiO 2-NH 2: isotherms, kinetic and process optimization. RSC Adv. 2015;5:11837–11844. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiziltaş H., Tekin T., Tekin D.J.C.E.C. Preparation and characterization of recyclable Fe3O4@ SiO2@ TiO2 composite photocatalyst, and investigation of the photocatalytic activity. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hou X., Zhao C., Tian Y., Dou S., Zhang X., Zhao J. Preparation of functionalized Fe 3 O 4@ SiO 2 magnetic nanoparticles for monoclonal antibody purification. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2016;32:889–894. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Safaei-Ghomi J., Shahbazi-Alavi H., Babaei P. One-pot multicomponent synthesis of furo [3, 2-c] coumarins promoted by amino-functionalized Fe3O4@ SiO2 nanoparticles. Z. Naturforsch. B. 2016;71:849–856. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu X., Dong Y., Pan F., Xiang Z., Liu Z., Deng B., Zhang X., Shi Z., Lu W. Covalent organic framework-derived hollow core-shell Fe/Fe3O4@ porous carbon composites with corrosion resistance for lightweight and efficient microwave absorption. Compos. Commun. 2021;25 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foroutan R., Peighambardoust S.J., Ahmadi A., Akbari A., Farjadfard S., Ramavandi B. Adsorption mercury, cobalt, and nickel with a reclaimable and magnetic composite of hydroxyapatite/Fe3O4/polydopamine. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021;9 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foroutan R., Mohammadi R., Ahmadi A., Bikhabar G., Babaei F., Ramavandi B. Impact of ZnO and Fe3O4 magnetic nanoscale on the methyl violet 2b removal efficiency of the activated carbon oak wood. Chemosphere. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kamari S., Shahbazi A. Biocompatible Fe3O4@ SiO2-NH2 nanocomposite as a green nanofiller embedded in PES–nanofiltration membrane matrix for salts, heavy metal ion and dye removal: long–term operation and reusability tests. Chemosphere. 2020;243 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khoshnam M., Salimijazi H. Synthesis and characterization of magnetic-photocatalytic Fe3O4/SiO2/a-Fe2O3 nano core-shell. Surface. Interfac. 2021;26 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saikia D., Borah J. Investigations of doping induced structural, optical and magnetic properties of Ni doped ZnS diluted magnetic semiconductors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2017;28:8029–8037. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu H., Wang C., Qin Y., Huang Y., Xiao C. Oriented structure design and evaluation of Fe3O4/o-MWCNTs/PVC composite membrane assisted by magnetic field. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021;120:278–290. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu D., Tan X., Chen C., Wang X. Adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solution to MX-80 bentonite: effect of pH, ionic strength, foreign ions and temperature. Appl. Clay Sci. 2008;41:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhou Y.-T., Nie H.-L., Branford-White C., He Z.-Y., Zhu L.-M. Removal of Cu2+ from aqueous solution by chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles modified with α-ketoglutaric acid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009;330(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mahdavi M., Ahmad M.B., Haron M.J., Gharayebi Y., Shameli K., Nadi B. Fabrication and characterization of SiO2/(3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane-coated magnetite nanoparticles for lead (II) removal from aqueous solution. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2013;23(3):599–607. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kobylinska N., Kostenko L., Khainakov S., Garcia-Granda S. Advanced core-shell EDTA-functionalized magnetite nanoparticles for rapid and efficient magnetic solid phase extraction of heavy metals from water samples prior to the multi-element determination by ICP-OES. Microchim. Acta. 2020;187(5):1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00604-020-04231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saleh T.A., Tuzen M., Sarı A. Polyethylenimine modified activated carbon as novel magnetic adsorbent for the removal of uranium from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2017;117:218–227. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang J., Lu X., Ng P.F., Lee K.I., Fei B., Xin J.H., Wu J.-y. Polyethylenimine coated bacterial cellulose nanofiber membrane and application as adsorbent and catalyst. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;440:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Annadurai G., Ling L.Y., Lee J.-F. Adsorption of reactive dye from an aqueous solution by chitosan: isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. J. Hazard Mater. 2008;152:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bao S., Tang L., Li K., Ning P., Peng J., Guo H., Zhu T., Liu Y. Highly selective removal of Zn (II) ion from hot-dip galvanizing pickling waste with amino-functionalized Fe3O4@ SiO2 magnetic nano-adsorbent. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;462:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taghipour T., Karimipour G., Ghaedi M., Asfaram A. Mild synthesis of a Zn (II) metal organic polymer and its hybrid with activated carbon: application as antibacterial agent and in water treatment by using sonochemistry: optimization, kinetic and isotherm study. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;41:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bilgic A., Cimen A., Kursunlu A.N., Karapınar H.S. Novel fluorescent microcapsules based on sporopollenin for removal and detection of Cu (II) ions in aqueous solutions: eco-friendly design, fully characterized, photophysical&physicochemical data. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022;330 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nejadshafiee V., Islami M.R. Adsorption capacity of heavy metal ions using sultone-modified magnetic activated carbon as a bio-adsorbent. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2019;101:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Abbas M. Modeling of adsorption isotherms of heavy metals onto Apricot stone activated carbon: two-parameter models and equations allowing determination of thermodynamic parameters. J. Mat. Pr. 2021;43:3359–3364. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Behbahani E.S., Dashtian K., Ghaedi M. Fe3O4-FeMoS4: promise magnetite LDH-based adsorbent for simultaneous removal of Pb (II), Cd (II), and Cu (II) heavy metal ions. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;410 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fan S., Wang Y., Li Y., Tang J., Wang Z., Tang J., Li X., Hu K. Facile synthesis of tea waste/Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticle composite for hexavalent chromium removal from aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2017;7:7576–7590. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mubarak M., Jeon H., Islam M.S., Yoon C., Bae J.-S., Hwang S.-J., San Choi W., Lee H.-J. One-pot synthesis of layered double hydroxide hollow nanospheres with ultrafast removal efficiency for heavy metal ions and organic contaminants. Chemosphere. 2018;201:676–686. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ngah W.W., Fatinathan S. Adsorption characterization of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions onto chitosan-tripolyphosphate beads: kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2010;91(4):958–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xie J., Lin R., Liang Z., Zhao Z., Yang C., Cui F. Effect of cations on the enhanced adsorption of cationic dye in Fe3O4-loaded biochar and mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ebrahim S.E., Sulaymon A.H., Saad Alhares H. Competitive removal of Cu2+, Cd2+, Zn2+, and Ni2+ ions onto iron oxide nanoparticles from wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2016;57:20915–20929. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huang S.-H., Chen D.-H. Rapid removal of heavy metal cations and anions from aqueous solutions by an amino-functionalized magnetic nano-adsorbent. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;163:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hua R., Li Z. Sulfhydryl functionalized hydrogel with magnetism: synthesis, characterization, and adsorption behavior study for heavy metal removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2014;249:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qin L., Yan L., Chen J., Liu T., Yu H., Du B. Enhanced removal of Pb2+, Cu2+, and Cd2+ by amino-functionalized magnetite/kaolin clay. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016;55:7344–7354. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feng G., Ma J., Zhang X., Zhang Q., Xiao Y., Ma Q., Wang S. Magnetic natural composite Fe3O4-chitosan@ bentonite for removal of heavy metals from acid mine drainage. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;538:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Safa M., Larouci M., Meddah B., Valemens P. The sorption of lead, cadmium, copper and zinc ions from aqueous solutions on a raw diatomite from Algeria. Water Sci. Technol. 2012;65:1729–1737. doi: 10.2166/wst.2012.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang Y.-C., Chen D.-H. Preparation and adsorption properties of monodisperse chitosan-bound Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles for removal of Cu (II) ions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005;283:446–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hao Y.-M., Man C., Hu Z.-B. Effective removal of Cu (II) ions from aqueous solution by amino-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles. J. Hazard Mater. 2010;184:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhou L.-C., Li Y.-F., Bai X., Zhao G.-H. Use of microorganisms immobilized on composite polyurethane foam to remove Cu (II) from aqueous solution. J. Hazard Mater. 2009;167:1106–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Venkateswarlu S., Kumar B.N., Prathima B., SubbaRao Y., Jyothi N.V.V. A novel green synthesis of Fe3O4 magnetic nanorods using Punica Granatum rind extract and its application for removal of Pb (II) from aqueous environment. Arab. J. Chem. 2019;12:588–596. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu Y., Hu J., Wang J. Competitive adsorption of Pb (II), Cu (II) and Zn (II) onto xanthate-modified magnetic chitosan. J. Hazard Mater. 2012;221:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuwei C., Jianlong W. Preparation and characterization of magnetic chitosan nanoparticles and its application for Cu (II) removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2011;168:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mittal A., Ahmad R., Hasan I. Poly (methyl methacrylate)-grafted alginate/Fe3O4 nanocomposite: synthesis and its application for the removal of heavy metal ions. Desalination Water Treat. 2016;57:19820–19830. [Google Scholar]

- 92.González M., Pavlovic I., Barriga C. Cu (II), Pb (II) and Cd (II) sorption on different layered double hydroxides. A kinetic and thermodynamic study and competing factors. Chem. Eng. J. 2015;269:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Banerjee S.S., Chen D.-H. Fast removal of copper ions by gum Arabic modified magnetic nano-adsorbent. J. Hazard Mater. 2007;147:792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sarioglu M., Atay Ü., Cebeci Y. Removal of copper from aqueous solutions by phosphate rock. Desalination. 2005;181:303–311. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu M., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Shen Y., Zhao M., Pan G. Study on the adsorption of Ca2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+ by magnetic Fe3O4 yeast treated with EDTA dianhydride. Chem. Eng. J. 2011;168:737–745. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhu S., Khan M.A., Wang F., Bano Z., Xia M. Rapid removal of toxic metals Cu2+ and Pb2+ by amino trimethylene phosphonic acid intercalated layered double hydroxide: a combined experimental and DFT study. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;392 [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vijayalakshmi K., Gomathi T., Latha S., Hajeeth T., Sudha P. Removal of copper (II) from aqueous solution using nanochitosan/sodium alginate/microcrystalline cellulose beads. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;82:440–452. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singha B., Das S.K. Adsorptive removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solution and industrial effluent using natural/agricultural wastes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2013;107:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rakati K.K., Mirzaei M., Maghsoodi S., Shahbazi A. Preparation and characterization of poly aniline modified chitosan embedded with ZnO-Fe3O4 for Cu (II) removal from aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;130:1025–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Netto C.G., Toma H.E., Andrade L.H. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles as versatile carriers and supporting materials for enzymes. J. Mol. Catal. B. 2013;85:71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yuan X., Chai Y., Yuan R., Zhao Q. Improved potentiometric response of solid-contact lanthanum (III) selective electrode. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2013;779:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhu J., Wei S., Haldolaarachchige N., Young D.P., Guo Z. Electromagnetic field shielding polyurethane nanocomposites reinforced with core–shell Fe–silica nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115(31):15304–15310. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xin X., Wei Q., Yang J., Yan L., Feng R., Chen G., Du B., Li H. Highly efficient removal of heavy metal ions by amine-functionalized mesoporous Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012;184:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen F., Luo G., Yang W., Wang Y. Preparation and adsorption ability of polysulfone microcapsules containing modified chitosan gel. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2005;10(5):535–541. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aryee A.A., Mpatani F.M., Du Y., Kani A.N., Dovi E., Han R., Li Z., Qu L. Fe3O4 and iminodiacetic acid modified peanut husk as a novel adsorbent for the uptake of Cu (II) and Pb (II) in aqueous solution: characterization, equilibrium and kinetic study. Environ. Pollut. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang B., Zhu Y., Bai Z., Luque R., Xuan J. Functionalized chitosan biosorbents with ultra-high performance, mechanical strength and tunable selectivity for heavy metals in wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;325:350–359. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xu J., Xu X., Zhao H., Luo G. Microfluidic preparation of chitosan microspheres with enhanced adsorption performance of copper (II) J. Sens. B. 2013;183:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Luo S., Xu X., Zhou G., Liu C., Tang Y., Liu Y. Amino siloxane oligomer-linked graphene oxide as an efficient adsorbent for removal of Pb (II) from wastewater. J. Hazard Mater. 2014;274:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.