Abstract

Objectives

Mandatory audiological testing before autism spectrum disorder (ASD) assessment is common practice. Hearing impairment (HI) in the general paediatric population is estimated at 3%; however, hearing impairment prevalence among children with ASD is poorly established. Our objective was to determine which children referred for ASD assessment require preliminary audiological assessment.

Methods

Retrospective chart review of children (n=4,173; 0 to 19 years) referred to British Columbia’s Autism Assessment Network (2010 to 2014). We analyzed HI rate, risk factors, and timing of HI diagnosis relative to ASD referral.

Results

ASD was diagnosed in 53.4%. HI rates among ASD referrals was 3.3% and not significantly higher in children with ASD (ASD+; 3.5%) versus No-ASD (3.0%). No significant differences in HI severity or type were found, but more ASD+ females (5.5%) than ASD+ males (3.1%) had HI (P<0.05). Six HI risk factors were significant (problems with intellect, language, vision/eye, ear, genetic abnormalities, and prematurity) and HI was associated with more risk factors (P<0.01). Only 12 children (8.9%) were diagnosed with HI after ASD referral; all males 6 years or younger and only one had no risk factors. ASD+ children with HI were older at ASD referral than No-ASD (P<0.05).

Conclusions

Children with ASD have similar hearing impairment rates to those without ASD. HI may delay referral for ASD assessment. As most children were diagnosed with HI before ASD referral or had at least one risk factor, we suggest that routine testing for HI among ASD referrals should only be required for children with risk factors.

Keywords: Age of diagnosis, Audiological assessment, Autism spectrum disorder, Hearing impairment, Paediatric

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with deficits in reciprocal social interaction, communication, and restrictive and repetitive behaviours and interests. ASD prevalence is rising, currently estimated as high as 1:54 children in the USA, with male predominance (1) and reported to be higher in children with neurological disorders, visual or hearing impairment (HI) (2). Many ASD assessment centres therefore require audiological evaluation before developmental-behavioural assessment for ASD; however, studies examining HI rates in children with ASD are conflicting and primarily rely on small sample sizes (3).

We therefore examined HI prevalence in a large population-based sample of ASD referrals. Our study aimed to evaluate whether audiology testing is required for every child referred for ASD assessment, by identifying risk factors (commonly reported during ASD assessment) that increase the likelihood of HI. We hypothesized that HI rates from the general paediatric population (estimated around 3%) (4) would not differ for children with ASD, as long as there are no other risk factors. In addition, we investigated whether audiology testing with ASD assessment contributes to the recognition of HI, or if HI is diagnosed prior, regardless of ASD diagnosis.

METHODS

With approval from the University of British Columbia (BC) Research Ethics Board, Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of BC Research Review Committee (H14-02084), data were collected from 4,213 assessments for children 0 to 19 years referred from BC’s Lower Mainland to the British Columbia Autism Assessment Network (BCAAN) between January 2010 and December 2014. Our dataset included ICD (International Classification of Diseases) and DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) codes entered by clinicians in the BCAAN database and were confirmed and supplemented by an independent chart reviewer. Most (98%) assessment reports were available for review and no significant differences in ASD status or gender existed between those available versus unavailable for review. Children with unavailable reports were significantly older (median 7 years versus 6 years) at diagnosis. Two unavailable reports included children with HI, so all assessments were analyzed. Children assessed more than once through BCAAN had their previous assessments excluded (n=39). One assessment was excluded for non-completion resulting in 4,173 assessments.

As part of the standard of care for the BCAAN assessment program, following referral, all children are required to undergo a hearing assessment by a qualified practitioner before ASD assessment. BCAAN also requires standardized testing for all children including the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised (ADI–R) (5) and appropriate level Autism Diagnosis Observation Schedule (ADOS/ADOS-2) (6,7). If diagnoses are unclear, additional age appropriate tests (e.g., intellectual disability, language, genetics) are administered by qualified practitioners. ASD diagnosis is made by a BCAAN qualified specialist using assessments and clinical judgment.

Hearing impairment

Classification of HI was based on audiological reports in patient charts. Certified audiologists using developmentally appropriate assessment techniques tested the children and interpreted the findings. All types and degrees of HI (mild to profound, bilateral and unilateral) were included. The hearing status of the poorer ear was used to classify each patient’s overall degree of HI. These decisions were based on the literature showing all HI levels may be clinically significant and even mild or unilateral HI might influence a child’s language development and function (8–11).

Risk factors

We examined factors available in our dataset that have been associated with HI (12–18). These included prematurity, neonatal ventilation, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, structural brain abnormality, genetic anomalies, vision impairment and ocular abnormality, history of ear infections, otitis media or ventilation tubes, language impairment, cerebral palsy, and intellectual disability. ‘Intellectual disability’ refers to diagnoses by qualified clinicians using age appropriate standardized tests. ‘Genetic conditions’ include genetic anomalies, whether associated with HI or not, including genetic syndromes, chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations, and deletions/duplications. ‘Language impairment’ includes disorders or delays in speech or language that were formally diagnosed or suspected (noted to be ruled out in future).

Analysis

Rates of co-morbid HI and ASD were analyzed with Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, z-score or Mann–Whitney tests. Multiple comparisons were corrected with the Bonferroni method. Logistic regression and Univariate Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were used to identify and characterize HI risk factors. Effect size was demonstrated with Cramer’s V, Partial eta squared (ηp2), or Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) where appropriate. SPSS version 26 was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

ASD was diagnosed in 53.4% (n=2,228) of our cohort (ASD+), and 46.6% (n=1,945) were negative for ASD (No-ASD). In our entire cohort, 3.3% of the patients (n=137) had a HI diagnosis. HI in the ASD+ group was 3.5% (n=78), which did not significantly differ from the No-ASD group (3.0%, n=59; Fisher’s exact test P=0.43, OR=0.86, CI=0.61 to 1.22).

Age

Children were assessed for ASD at 1 to 19 years with most children assessed at younger ages (median age 5.7 years). Those diagnosed ASD+ compared to No-ASD, had significantly lower median ages of referral (4.1 versus 6.0 years, Mann–Whitney P<0.05) and diagnosis (4.8 versus 6.8 years, Mann–Whitney P<0.05). The median age of both referral and diagnosis of children with HI in our sample was higher in the ASD+ group, but lower in the No-ASD group (Table 1).

Table 1.

ASD and hearing impairment according to gender and age

| ASD Status | Hearing Impairment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | No HI | HI | x2Sig. | Odds Ratio M/F (95% CI) | |

| No-ASD | Female: n (%) | 392 (95.8%) | 17 (4.2%) | 0.14 | 1.54 (0.87–2.74) |

| Male: n (%) | 1,494 (97.3%) | 42 (2.7%) | |||

| ASD+ | Female: n (%) | 375 (94.5%) | 22 (5.5%) | *0.02 | 1.86 (1.12–3.08) |

| Male: n (%) | 1,775 (96.9%) | 56 (3.1%) | |||

| Total | Female: n (%) | 767 (95.2%) | 39 (4.8%) | *0.01 | 1.70 (1.16–2.48) |

| Male: n (%) | 3,269 (97.1%) | 98 (2.9%) | |||

| ASD Referral Age(years) |

No HI | HI | Mann–Whitney Sig. |

Percentile | |

| 25th–75th | |||||

| No-ASD | Median (range 0–19) | 6.1 | 4.8 | *0.01 | 4.00–9.50 |

| ASD+ | Median (range 0–19) | 4.1 | 5.2 | *0.02 | 2.75–7.17 |

| Total | Median (range 0–19) | 5 | 5.2 | 0.81 | 3.17–8.50 |

| ASD Diagnosis Age(years) |

No HI | HI | Mann–Whitney Sig. | Percentile | |

| 25th–75th | |||||

| No-ASD | Median (range 1–19) | 6.8 | 5.7 | *0.02 | 4.75–10.17 |

| ASD+ | Median (range 1–19) | 4.8 | 5.7 | *0.02 | 3.42–7.83 |

| Total | Median (range 1–19) | 5.8 | 5.7 | 0.62 | 3.92–9.17 |

Rates of hearing impairment according to ASD status, gender, ASD referral age and ASD diagnosis age.

ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder; CI Confidence Intervals; HI Hearing impairment; Sig. Significance.

*P<0.05.

Gender

The male:female ratio in our cohort was 4.18:1 (n=3,367:806). Significantly more females than males were diagnosed with HI, but when split according to ASD status, only the ASD+ group had significantly more females than males with HI (Table 1).

Type of hearing impairment

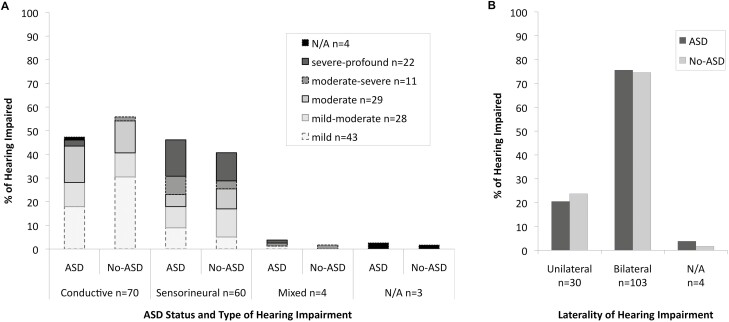

Chi-square analyses showed no significant differences between the ASD+ and No-ASD groups for HI level (x2=2.07, df=4, P=0.72; Figure 1a), type (conductive, sensorineural, mixed; x2=1.23, df=2, P=0.54; Figure 1a) or unilateral versus bilateral HI; x2=0.15, df=1, P=0.70; Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Hearing impairment according to ASD group status divided by (A) Level (mild-profound) and Type (Conductive or Sensorineural) and (B) Unilateral versus Bilateral. ASD Autism spectrum disorder. ‘Mixed’ refers to children with both conductive and sensorineural hearing impairment and ‘N/A’ refers to data that was not available.

Risk factors for hearing impairment

A logistic regression analyzing HI (adjusting for ASD status, gender, and age of referral) with 12 risk factors available in our dataset found six significant for HI in our population: intellectual disability, language impairment, vision/eye abnormalities, ear abnormalities/recurrent otitis media or ear infections/history of ventilation tubes, genetic conditions, and prematurity (all P<0.05; Table 2). In our entire cohort, 33.3% had none of our identified risk factors. In our HI sample, 94.2% had at least one of our risk factors.

Table 2.

Factors associated with hearing impairment.

| B | SE | Sig. | Exp(B) | **Adjusted 95% CI-Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Prematurity | 0.55 | 0.25 | *0.03 | 1.73 | 1.05 | 2.84 |

| Neonatal ventilation/CPAP/intubation | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 1.2 | 0.43 | 3.37 |

| Phototherapy | 0.2 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 1.22 | 0.51 | 2.91 |

| Brain abnormality | 0.58 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 1.79 | 0.86 | 3.72 |

| Macrocephaly | 0.5 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 1.65 | 0.7 | 3.9 |

| Microcephaly | 0.29 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 1.34 | 0.49 | 3.67 |

| Genetic anomaly | 1.75 | 0.23 | *<0.001 | 5.75 | 3.7 | 8.95 |

| Vision/eye disorder | 0.73 | 0.23 | *<0.001 | 2.07 | 1.33 | 3.22 |

| Ear infections/otitis media/ventilation tubes | 1.29 | 0.22 | *<0.001 | 3.63 | 2.38 | 5.54 |

| Language impairment | 0.45 | 0.19 | *0.02 | 1.57 | 1.09 | 2.28 |

| Cerebral palsy | 1.18 | 1.07 | 0.27 | 3.27 | 0.4 | 26.63 |

| Intellectual disability | 0.85 | 0.21 | *<0.001 | 2.34 | 1.55 | 3.53 |

| Constant | −2.75 | 0.95 | 0 | 0.06 |

Results of multivariate logistic regression analysis examining factors associated with hearing impairment available in our dataset.

ASD Autism spectrum disorder; CI Confidence interval; SE Standard error; Sig. Significance.

*P<0.05, **Adjusted for ASD status, gender, and age at referral

Follow-up analysis of each of our six identified risk factors with multivariate logistic regression examined ASD status, gender, age of referral (<6 or >6 years) and HI. Among the ASD+, intellectual disability, and genetic conditions were more frequently observed compared to the No-ASD group, while ear conditions and language impairment were more frequent in the No-ASD versus ASD+ group (all P<0.05; Table 3). More frequent among females than males were intellectual disability, vision/eye, and genetic conditions (all P<0.05; Table 3). Children referred for ASD assessment under age 6 years were more likely to have language impairment, while children referred over age 6 years had more vision/eye conditions (all P<0.05; Table 3). Children with HI had significantly more of each risk factor than children without HI (all P<0.05; Table 3).

Table 3.

Hearing impairment risk factors according to ASD status, gender, ASD referral age, and presence of hearing impairment

| B | SE | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intellectual Disability | ASD status = ASD+ | 0.64 | 0.09 | *<0.001 | 1.89 | 1.58 | 2.26 |

| Gender = Female | 0.61 | 0.10 | *<0.001 | 1.85 | 1.52 | 2.24 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.21 | 1.12 | 0.94 | 1.34 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 1.49 | 0.18 | *<0.001 | 4.43 | 3.11 | 6.32 | |

| Language Impairment | ASD status = ASD+ | −0.42 | 0.07 | *<0.001 | 0.66 | 0.58 | 0.75 |

| Gender = Female | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | 1.10 | 0.07 | *<0.001 | 3.01 | 2.63 | 3.44 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 0.39 | 0.18 | *0.03 | 1.48 | 1.04 | 2.12 | |

| Ear Conditions | ASD status = ASD+ | −0.30 | 0.11 | *0.01 | 0.74 | 0.60 | 0.92 |

| Gender = Female | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 1.22 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.47 | 0.92 | 0.74 | 1.15 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 1.50 | 0.20 | *<0.001 | 4.49 | 3.05 | 6.60 | |

| Vision/Eye Conditions | ASD status = ASD+ | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.14 | 1.16 | 0.95 | 1.40 |

| Gender = Female | 0.70 | 0.11 | *<0.001 | 2.02 | 1.63 | 2.50 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | −1.04 | 0.10 | *<0.001 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.43 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 1.24 | 0.20 | *<0.001 | 3.44 | 2.34 | 5.06 | |

| Genetic Conditions | ASD status = ASD+ | 0.52 | 0.14 | *<0.001 | 1.67 | 1.27 | 2.21 |

| Gender = Female | 0.95 | 0.14 | *<0.001 | 2.59 | 1.96 | 3.42 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | −0.10 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 1.19 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 2.33 | 0.20 | *<0.001 | 10.32 | 7.02 | 15.18 | |

| Premature | ASD status = ASD+ | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 1.08 | 0.87 | 1.33 |

| Gender = Female | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 1.18 | 0.92 | 1.51 | |

| Referral Age =< 6 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 1.38 | |

| Hearing Impaired = yes | 0.88 | 0.22 | *<0.001 | 2.40 | 1.56 | 3.68 |

Multivariate regression analyses of each of our six identified Risk Factors (for hearing impairment) showing differences for ASD group status, gender, ASD referral age and hearing impairment.

ASD Autism spectrum disorder; CI Confidence interval; SE Standard error; Sig. Significance.

*P<0.05.

The number of risk factors for each child was examined using a univariate ANOVA with ASD status, gender, and hearing impairment. Interaction terms were included for ASD status and gender as well as ASD status and HI. Main effects were found for both gender and HI, but not ASD status. Females had significantly more risk factors (1.2) than males (0.9) (F(5,4167)=44.99, P<0.001,ηp2=0.01), and those with HI had significantly more risk factors (2.2) than those without HI (1.0) (F(5,4167)=219.55, P<0.001, ηp2=0.05). No significant interactions were found between ASD status and gender or ASD status and HI.

Timing of hearing impairment diagnosis

Among those with HI, 8.9%(12/135) were diagnosed with HI following their referral for ASD assessment (Timing of HI diagnosis unavailable for one patient with ASD and one patient without ASD). Of those, 5.2%(4/77) had ASD+ and 13.8%(8/58) had No-ASD, with no significant difference between ASD+ and No-ASD (Fisher’s exact test P=0.13). All four ASD+ had conductive HI, (two mild, one mild-moderate and one moderate), one was unilateral. By the time of ASD assessment, HI for two patients had resolved. In the No-ASD group, half (n=4) had conductive HI (two mild, one mild-moderate, and one moderate) and half had sensorineural HI (two mild-moderate, one moderate, and one severe), one was unilateral.

All 12 patients diagnosed with HI after the ASD referral were males age 6 years or younger at ASD diagnosis. Seven had language impairment, six had intellectual disability, two had genetic abnormalities, one had ventilation tubes, none had vision/eye conditions, one had a history of prematurity, two had seizure disorders, and one had microcephaly. Six had one of our identified risk factors, four had two risk factors, and one had three risk factors. Only one patient had no risk factors, and had mild conductive bilateral HI, but not ASD.

Age of ASD referral

We followed up on our finding that children with ASD+ and HI were referred at significantly older ages than children with ASD+ but without HI (Table 1). Age of referral was investigated because we were interested in the age at which concerns about development prompted referral for ASD assessment. To prevent biasing our data, results were calculated without children diagnosed with HI following ASD referral (n=12) or where timing of hearing testing was unavailable (n=2). Only children with HI diagnoses before referral for ASD were analyzed (n=123).

We divided referral age into 4-year blocks, ages 0 to 3, 4 to 7, 8 to 11, 12 to 15, and 16+. Chi-square analyses examining age of referral and HI according to ASD status showed a significant difference between ages in the ASD+ group (x2=11.15, df=4, P=0.025, Cramer’s V=0.07), but not the No-ASD group (x2=1.62, df=4, P=0.805, Cramer’s V=0.03; Figure 2). Follow-up z-score analysis showed significantly more ASD+ children with HI were referred between ages 8 to 11 compared to ASD+ children without HI (P<0.05, Bonferroni corrected; Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Number of children referred for ASD assessment grouped according to age and divided by hearing impairment status for (A) Children with ASD, (B) Children without ASD. ASD Autism spectrum disorder; HI Hearing impairment. *P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

At the time of ASD assessment, HI rates in children with ASD were similar to those without ASD and the general paediatric population (4). No differences were found for type of HI, severity or ears affected between ASD+ and No-ASD groups. Most children were diagnosed with HI before referral for ASD assessment. More children with HI and ASD were referred for ASD assessment at an older age.

HI prevalence in the general paediatric population varies with age and mild HI is found in 3.1% of children and adolescents (4), similar to the rates in our study. Prevalence of HI among children with ASD is debated, as some studies demonstrate higher rates of HI among children with ASD, while others denied such elevation (3). A review of 2,568 health records for children with ASD found 1.7% had hearing loss (19). Studies comparing typically developing children to those with ASD who are high functioning (20), or have varying cognitive function (21) found no differences in hearing. Rosenhall and colleagues (22) estimated prevalence of pronounced to profound hearing loss at 3.5% in children with ASD.

We identified six risk factors associated with HI, including intellectual disability; language impairment; vision impairment/eye abnormality; recurrent ear infections/otitis media or history of ventilation tubes; genetic disorders; and history of prematurity. More risk factors per child were associated with higher incidence of HI.

In our cohort, females with ASD had higher rates of HI and were more likely to have intellectual disability, vision/eye abnormalities, and genetic disorders. Females with ASD may have higher rates of HI, as differences in clinical ASD characteristics exist between females and males (23,24). Variations in brain function and connectivity (25), and possibly higher rates of neurological comorbidities exist in females with ASD (26).

Our data shows children with HI and ASD were older when referred for ASD assessment, and this corresponds with studies reporting later age of ASD diagnosis in the presence of co-morbid HI (19,27–29). HI features may delay referral and subsequent diagnosis of ASD as similarities exist between ASD features and HI (30–33). It should not be assumed that ‘autistic’ traits are a consequence of HI, and referral for ASD assessment should be made as early as possible if in doubt.

Most children with HI in our cohort were diagnosed with HI before, and regardless of, their referral for ASD assessment. Interestingly, with over 4,000 patients, limiting audiology testing to children with at least one of our six risk factors would have missed only one child with mild conductive HI. Additionally, one third of our sample would have not required audiological testing. This study is not meant to replace current recommendations for audiology assessment in the general paediatric population but, rather, question the need for a routine assessment for every child with suspected ASD.

This study’s strength is cohort size, examining HI in a large population assessed for ASD, including most children referred for ASD assessment in BC’s lower mainland over 5 years. We also accessed the children’s audiological assessments to determine HI characteristics and timing of diagnosis.

Our retrospective study is, however, limited by information obtained during ASD assessment, including lack of information on the type of audiological assessment measures, whether impairment was permanent, transient or fluctuating, as well as clinician reporting biases and some parental recall. However, these biases were present in both groups and should not influence differences found between ASD+ and No-ASD subgroups. When comparing HI rates, we did not include a ‘typically developing’ group, but compared our findings to literature from the general paediatric population. While many risk factors for HI were available in our dataset, other important possible risk factors (12–18) such as family history of HI and medications like aminoglycosides and chemotherapy were not available in our dataset. Further, our results may not generalize to all individual practitioners as they are from a population-based government funded network.

While our findings indicate that most children were diagnosed with HI before referral, this may be biased. The BC provincial newborn hearing screening program was introduced at the end of 2007 and was in place in most hospitals/clinics by 2009 (http://www.phsa.ca/our-services/programs-services/bc-early-hearing-program). We are unaware of which children underwent newborn screening, but the number would be limited. Only 17(12.4%) children with HI were born in 2008, and 26(19.0%) in 2009 or later. Of those, seven were diagnosed with HI ‘after’ ASD referral (i.e., not detected as newborn).

CONCLUSIONS

At the time of ASD assessment, HI rates are similar for both children with and without ASD. Children with both ASD and HI were older at referral for ASD assessment, suggesting HI may delay ASD referral. Most children had been diagnosed with HI before ASD referral and had at least one of six identified risk factors. Future research could investigate the potential for a decrease in wait time for ASD assessment by limiting the requirement of audiological assessment to those children with risk factors. Our aim is not to change current recommendations regarding hearing assessment for risk groups in the general paediatric population. Rather, our aim is to ensure audiologic assessment for any child with a known risk factor and discourage mandatory audiologic assessment based on ASD referral only. Guidelines for referral to audiology before ASD assessment should be established and follow-up research is needed to assess effects of such guidelines.

Contributor Information

Ram A Mishaal, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Whitney M Weikum, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Beth Brooks, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; School of Audiology and Speech Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Karen Derry, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; School of Audiology and Speech Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Nancy E Lanphear, Sunny Hill Health Centre for Children, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

FUNDING

All phases of this study were supported by the Sunny Hill Foundation for Children (which is part of the BC Children’s Hospital Foundation).

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

WMW disclosed that the Sunny Hill Foundation for Children (which is part of the BC Children’s Hospital Foundation) funds a portion of her salary. All other authors had no conflicts to declare. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1. Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2020;69(4):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Do B, Lynch P, Macris EM, Smyth B, Stavrinakis S, Quinn S, Constable PA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association of autism spectrum disorder in visually or hearing impaired children. Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics. 2017;37(2):212–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beers AN, McBoyle M, Kakande E, Dar Santos RC, Kozak FK. Autism and peripheral hearing loss: A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78(1):96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehra S, Eavey RD, Keamy DG Jr. The epidemiology of hearing impairment in the United States: Newborns, children, and adolescents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140(4):461–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Le Couteur A, Rutter M, Lord C.. The Autism Diagnostic Interview V Revised (ADI-R). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S.. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule V Generic. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lord C, DiLavore PC, Gotham K, Guthrie W, Luyste RJ.. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, second edition (ADOS-2). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tharpe AM. Unilateral and mild bilateral hearing loss in children: past and current perspectives. Trends Amplif 2008;12(1):7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Demopoulos C, Lewine JD. Audiometric profiles in autism spectrum disorders: Does subclinical hearing loss impact communication? Autism Res 2016;9(1):107–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winiger AM, Alexander JM, Diefendorf AO. Minimal hearing loss: From a failure-based approach to evidence-based practice. Am J Audiol 2016;25(3):232–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rohlfs AK, Friedhoff J, Bohnert A, et al. Unilateral hearing loss in children: A retrospective study and a review of the current literature. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176(4):475–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kountakis SE, Skoulas I, Phillips D, Chang CY. Risk factors for hearing loss in neonates: A prospective study. Am J Otolaryngol 2002;23(3):133–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herer GR. Intellectual disabilities and hearing loss. Communication Disorders Quarterly 2012;33(4):252– 60. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lasak JM, Allen P, McVay T, Lewis D. Hearing loss: Diagnosis and management. Prim Care 2014;41(1):19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wroblewska-Seniuk K, Greczka G, Dabrowski P, et al. Hearing impairment in premature newborns-Analysis based on the national hearing screening database in Poland. PLoS One 2017;12(9):e0184359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weir FW, Hatch JL, McRackan TR, Wallace SA, Meyer TA. Hearing loss in pediatric patients with cerebral palsy. Otol Neurotol 2018;39(1):59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vanneste P, Page C. Otitis media with effusion in children: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. A review. J Otol 2019;14(2):33–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing. Year 2019 position statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. The journal of early hearing impairment and intervention 2019;4(2):1–44. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levy SE, Giarelli E, Lee LC, et al. Autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring developmental, psychiatric, and medical conditions among children in multiple populations of the United States. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2010;31(4):267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gravel J, Dunn M, Lee W, Ellis M. Peripheral audition of children on the autistic spectrum. Ear Hear 2006;27(3):299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tharpe AM, Bess FH, Sladen DP, Schissel H, Couch S, Schery T. Auditory characteristics of children with autism. Ear Hear 2006;27(4):430–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rosenhall U, Nordin V, Sandström M, Ahlsén G, Gillberg C. Autism and hearing loss. J Autism Dev Disord 1999;29(5):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hull L, Mandy W, Petrides KV. Behavioural and cognitive sex/gender differences in autism spectrum condition and typically developing males and females. Autism 2017;21(6):706–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ratto AB, Kenworthy L, Yerys B, et al. What about the girls? Sex-based differences in autistic traits and adaptive skills. J Autism Dev Disord 2018;48(5):1698–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smith REW, Avery JA, Wallace GL, Kenworthy L, Gotts SJ, Martin A. Sex differences in resting-state functional connectivity of the cerebellum in autism spectrum disorder. Front Hum Neurosci 2019;13:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ben-Itzchak E, Ben-Shachar S, Zachor DA. Specific neurological phenotypes in autism spectrum disorders are associated with sex representation. Autism Res 2013;6(6):596–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2005;116(6):1480–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kancherla V, Van Naarden Braun K, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Childhood vision impairment, hearing loss and co-occurring autism spectrum disorder. Disabil Health J 2013;6(4):333–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Szarkowski A, Flynn S, Clark T. Dually diagnosed: A retrospective study of the process of diagnosing autism spectrum disorders in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Semin Speech Lang 2014;35(4):301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grindle CR. Pediatric hearing loss. Pediatr Rev 2014;35(11):456–63; quiz 464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meinzen-Derr J, Wiley S, Bishop S, Manning-Courtney P, Choo DI, Murray D. Autism spectrum disorders in 24 children who are deaf or hard of hearing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78(1):112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miller M, Iosif AM, Hill M, Young GS, Schwichtenberg AJ, Ozonoff S. Response to name in infants developing autism spectrum disorder: A prospective study. J Pediatr 2017;183:141–146.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rashid SMU, Mukherjee D, Ahmmed AU. Auditory processing and neuropsychological profiles of children with functional hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2018;114:51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]