Table 6.

Summary of characteristics of different ORP types and their suggested interpretation and potential clinical implications

| ORP-Architecture Type* | Suggested Underlying Physiological Mechanism | Clinical Associations | Suggested Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

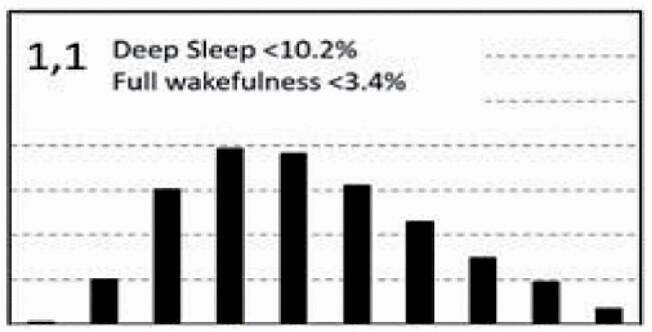

Little deep sleep suggests either low sleep drive or sleep-fragmenting disorder (OSA, other sources). Little full wakefulness and low ORPWAKE (Table 5) favor high, not low, sleep drive. Conclusion: Likely sleep fragmenting disorder ® high sleep pressure. | Rare at all ages in the general community (Figure 9). Frequency increases with OSA severity (Table 3). Associated with poor sleep quality (Table 5) and low QOL in unadjusted analysis (Table 4). |

Suggestive of a severe sleep-fragmenting disorder. Warrants investigation of cause. Cause may be evident in PSG (OSA, PLMs) or arousal stimuli may originate from other sources (pain, itching, etc.). If associated with OSA sleep is likely to improve with RX. |

|

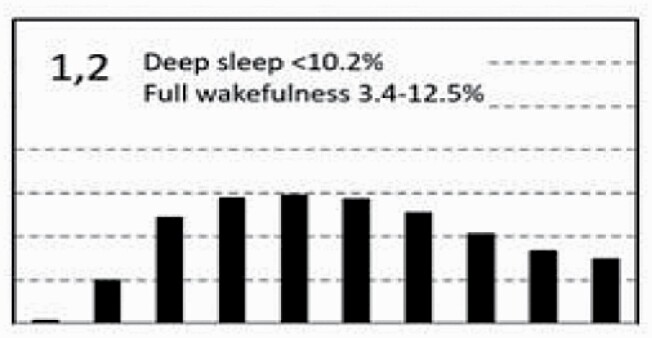

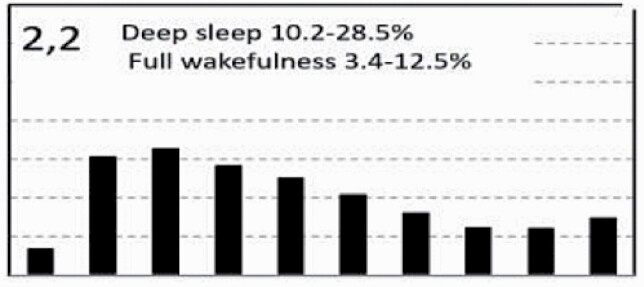

Little deep sleep suggests low sleep drive or sleep-fragmenting disorder. But average full wakefulness and normal ORPWAKE (Table 5) argue against low sleep drive. Conclusion: Likely sleep-fragmenting disorder. | Not uncommon in people with no OSA/insomnia (Table 3). Frequency increases with age (Figure 9) and OSA severity (Table 3). Associated with poor sleep quality (Table 5) and reduced QOL (Table 4). | Same as type 1,1, but less likely to be sleepy. May represent a mild form of type 1,3 (low sleep drive) particularly in the absence of an organic sleep-fragmenting disorder. |

|

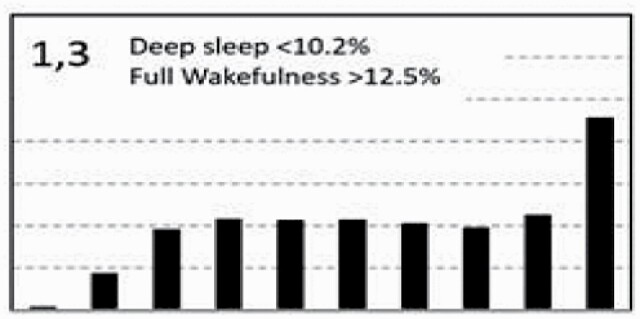

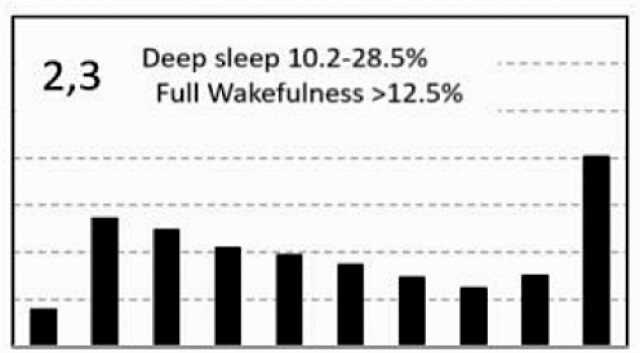

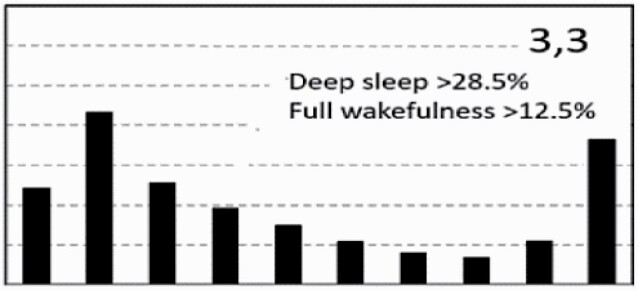

Little deep sleep suggests either low sleep drive or sleep-fragmenting disorder (OSA, other sources). But increased amount of full wakefulness and high ORPWAKE and ORP-9 (Table 5) strongly suggest low sleep drive. | Rare in young subjects but frequency increases with age (Figure 9) and markedly in very severe OSA, insomnia SSD and COMISA (Table 3). Associated with very poor sleep quality (Table 5) and reduced QOL (Table 4). | Normal in old people, particularly if asymptomatic. Occurrence in younger people or symptomatic older people is suggests a hyperarousal state. Frequently associated with severe OSA where concurrent Rx of insomnia may be considered. |

|

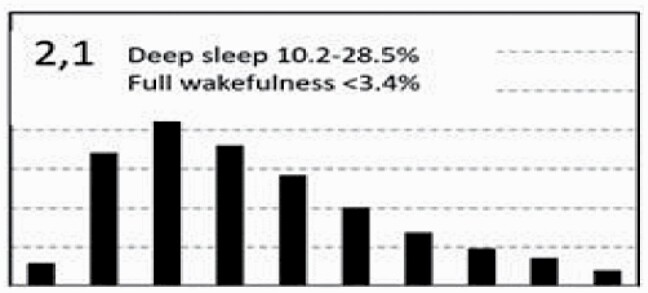

Average amounts of deep sleep and sleep depth (Table 5). Little time in full wakefulness and low ORPWAKE (Table 5) suggest insufficient sleep. | Average frequency with no tendency to increase in OSA or insomnia (Table 3). No association with reduced QOL (Table 4). | Likely normal but may benefit from increasing time in bed if excessively sleepy. |

|

Average deep sleep and normal sleep depth (Table 5) suggest normal sleep. Presence of moderate amount of full wakefulness suggests adequate restorative function. | Most frequent pattern in subjects without OSA or insomnia. Tendency to be lower in severe OSA and insomnia SSD (Table 3). No associated adverse health outcomes (Table 4). | Normal sleep. Symptoms, if any, are likely not related to poor sleep. |

|

Average deep sleep and sleep depth (Table 5) suggest adequate sleep quality. Excessive amount of full wakefulness despite adequate sleep quality suggests reduced sleep need or circadian misalignment. | Frequency increases markedly in old individuals (Figure 9) and dramatically in insomnia-SSD (Table 3). Associated with normal QOL on average (Table 4). Normal in the elderly but circadian misalignment possible if symptoms present. | Suggests decreased sleep need (short sleeper). Normal in the elderly if asymptomatic. Daytime symptoms suggest circadian misalignment or lifestyle issues. May be a common, less malignant form of insomnia-SSD. |

|

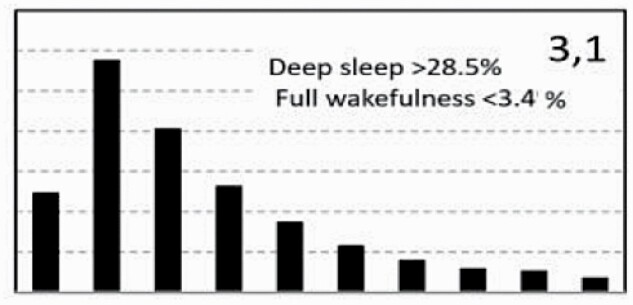

Excessive amount of deep sleep suggests prior sleep deprivation (Figure 5A) or chronic insufficient sleep. Little time in full wakefulness and low ORPWAKE (Table 5) suggest that sleep was not completely restorative. | Most frequent type in healthy young adults (Figure 9). Rare in older subjects (Figure 9). Tendency to lower frequency in severe OSA and insomnia-SSD. Associated with above average QOL (Table 4). | Normal in young adults. Presence in older adults or symptomatic young adults suggests prior sleep deprivation (Figure 5A). In absence of recent sleep loss, excessive sleep need (long sleeper, central hypersomnolence) is suggested. |

|

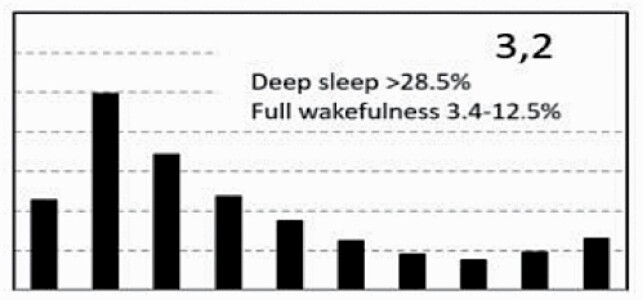

Excessive amounts of deep sleep suggest prior sleep deprivation (Figure 5A) but moderate amount of full wakefulness and average ORPWAKE argue against sleep deprivation. | No association with age (Figure 9) or gender (Supplementary Table S1). Tendency to be less frequent in severe OSA and insomnia SSD (Table 3). No associated adverse health outcomes (Table 4). | Normal sleep. Symptoms, if any, are likely not related to poor sleep. |

|

Combination of increased deep sleep and excessive amount of full wakefulness suggests short sleeper or circadian misalignment (see type 2,3, above). | Rare in all demographics (Figure 9 and Supplementary Table S1) with no association with OSA or insomnia (table 3). Not associated with adverse health outcomes (Table 4). | Suggests decreased sleep need if asymptomatic. Daytime symptoms suggest circadian misalignment or lifestyle issues. |

* Deep sleep refers to epochs with ORP < 0.5. Full wakefulness refers to epochs with ORP > 2.25. ORP, odds ratio product; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PLMs, periodic limb movement. QOL, quality of life. SSD, short sleep duration.