Abstract

Background

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) is a malignant soft tissue tumor that has been reclassified from malignant fibrous histiocytoma with the development of the pathological diagnosis. It principally occurs in the extremities but rarely occurs in the rectum. We herein report a rare case of UPS arising in the rectum.

Case presentation

A 85-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a complaint of anal pain, which had persisted for several months. Computed tomography (CT) showed a 53 × 58 × 75 mm mass on the left side of the rectum. Colonoscopy revealed a submucosal elevation in the rectum without any exposure of the tumor to the surface. Contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging revealed an 80-mm mass that originated in the rectal muscular propria, and we suspected a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. No lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis was observed. We performed a laparoscopic Hartmann’s operation. Intraoperatively, severe adhesion around the tumor caused tumor injury and right ureteral dissection. Thus, laparoscopic right ureteral anastomosis and ureteral stenting were additionally performed. The operation time was 6 h and 3 min, and the estimated blood loss was small. The patient was discharged without complications 25 days after surgery. A pathological examination showed that the tumor was composed of highly heterogeneous cells with no specific differentiation traits, leading to a diagnosis of UPS. Contrast-enhanced CT performed 2 months after surgery showed bilateral pelvic lymph node enlargement, which indicated recurrence. Considering the patient’s age, we performed radiotherapy (50 Gy/25 Fr targeting the pelvic region). At present, 16 months have passed since the completion of radiotherapy. Contrast-enhanced CT shows that the recurrent lymph nodes have disappeared, and no new distant metastasis has been observed.

Conclusions

We reported a case of UPS arising in the rectum. The surgical procedure and indication of preoperative therapy should be carefully selected because complete removal of the tumor is desirable in UPS.

Keywords: Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS), Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), Rectum, Surgery, Radiotherapy, Chemotherapy

Background

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) is a malignant soft tissue tumor that was reclassified from malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2002 and 2013 due to changes in the pathologic diagnosis [1]. Although the cells of origin of UPS have not been identified, it can occur anywhere in the body, most commonly in the extremities, but can also occur in the retroperitoneal space [2]. The occurrence of UPS in the rectum is very rare and has only been reported in a few cases. We herein report a rare case of UPS arising in the rectum of an adult female.

Case presentation

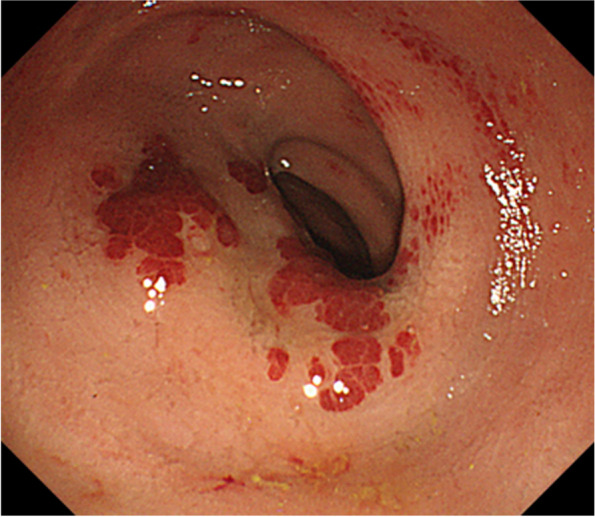

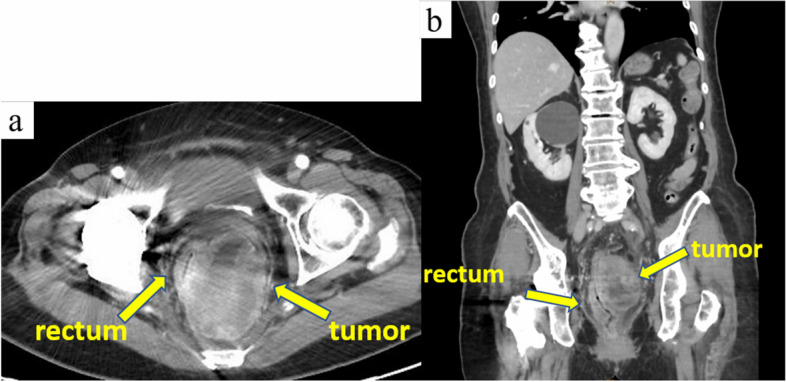

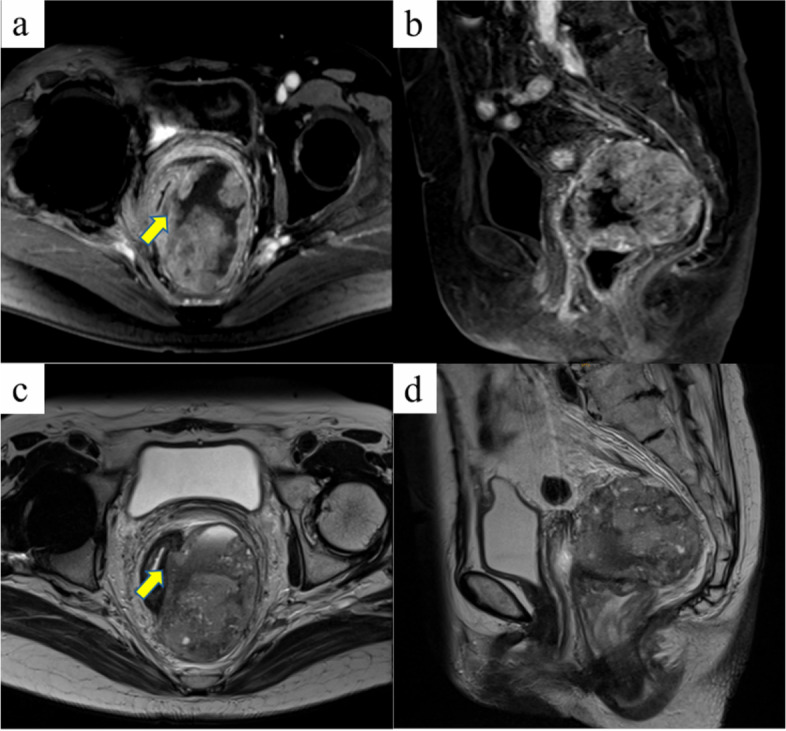

In 2020, an 85-year-old woman presented to her family doctor with a complaint of anal pain that had persisted for months. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a 53 × 58 × 75 mm mass on the left side of the rectum. She was admitted to our hospital for further examination and treatment. She had a medical history of open appendicectomy for appendicitis, open total hysterectomy for uterine fibroids, femoral head replacement for right femoral neck fracture, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. None of her family had a clear history of cancer. A hematological examination showed no elevation in tumor or inflammation markers, with the exception of CA125 (55 U/mL). On visual examination, there were no obvious abnormalities of the anus. On digital anorectal examination, an elastic hard mass was palpated on the left side of the rectum, and tenderness was present in the same region. Colonoscopy showed submucosal elevation and reddening of the mucosal surface in the central and lower rectum, but no obvious exposure of the tumor to the mucosal surface (Fig. 1). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a 53 × 58 × 75 mm mass lesion on the left side of the rectum with well-defined margins and heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Fluid accumulation was observed in the center of the mass, which suggested necrotic tissue (Fig. 2 a and b). No lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis was observed. Contrast-enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that the tumor was continuous with the muscular propria on the left side of the rectum (Fig. 3 a, b, c, and d). According to the imaging findings, we suspected that the tumor was a gastrointestinal stromal tumor, and we planned to obtain a pathological diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration. However, since the anal pain worsened rapidly and was uncontrollable despite the introduction of opioids, we decided to perform early surgery without a preoperative pathological diagnosis. A laparoscopic Hartmann’s operation was planned.

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopy showed submucosal elevation of the middle and lower rectum with mucosal surface erythema, but no exposure of the tumor to the mucosal surface

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a 53 × 58 × 75 mm mass with well-defined boundaries and a heterogeneous contrast effect on the left side of the rectum. Fluid accumulation was observed in the center of the mass, which suggested necrotic tissue

Fig. 3.

Contrast-enhanced pelvic magnetic resonance images. Coronal fat-suppressed T1-weighted (a), sagittal fat-suppressed T1-weighted (b), coronal T2-weighted (c), and sagittal T2-weighted images (d) are presented. The tumor was continuous with the muscular propria on the left side of the rectum (indicated by an arrow)

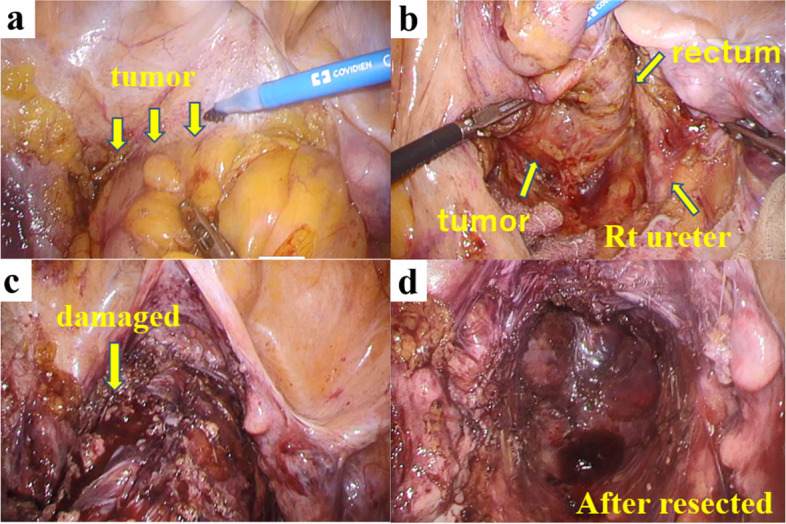

After administering general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position and underwent laparoscopic surgery using 5 ports. As in rectal surgery, the retroperitoneum was dissected caudally from the promontorium using a medial approach, and the rectal mesentery was mobilized. The tumor was located caudal to the peritoneal reversal and occupied the pelvic cavity (Fig. 4a). The tumor was so large that the rectum was pushed to the right side, and the border was unclear due to the surrounding inflammation (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Intraoperative findings. The tumor was located caudal to the peritoneal reversal and firmly adherent to the bladder and the vagina (a). The tumor was so large that the rectum was pushed to the right side (b). The tumor was damaged in the region, causing the leakage of dark red tumor contents (c). The rectum and tumor were removed by a Hartmann operation (d)

Therefore, dissection of the right side of the tumor was so difficult that the right ureter was misidentified and accidentally separated. The ventral side of the tumor was firmly adherent to the bladder, and the tumor was damaged at the region, causing the leakage of dark red tumor contents (Fig. 4c). The lower rectum with 6 cm of the anal verge was dissected using a linear stapler (Signia™, Medtronic, Tokyo, Japan) (Fig. 4d). The rectum was elevated outside the body, and the sigmoid colon was resected at a distance of 10 cm from the tumor. A sigmoid colon colostomy was constructed in the left lower abdomen. Finally, the right ureter was reconstructed, and a double-J catheter was placed. The operation time was 6 h and 3 min, and the amount of blood loss was small. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 25th postoperative day.

Macroscopic observation of the resected specimen revealed that the rectum and sigmoid colon were 300 mm in length. On the serous aspect, there was a 110 × 83 × 30 mm solid tumor with intraoperative damage and no obvious exposure to the mucosal surface (Fig. 5 a and b). The cut surface was white solid with necrosis and hemorrhage in the center (Fig. 6a). Histopathologically, tumor cell growth was mainly observed in the muscularis propria to the subserosal layer of the rectum with inflammatory cell infiltration, hemorrhage, and necrotic tissue at the center (Fig. 6b). The tumor cells were composed of pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, and many typical and atypical mitotic figures were observed (Fig. 7a). On immunostaining, the tumor cells were focally positive for cluster of differentiation (CD) 117/KIT, α-smooth muscle actin, AE1/AE3, and EMA and negative for CD34, DOG1, h-caldesmon, desmin, S100 protein, and CD45. Ki-67/MIB1 proliferation index was very high (Fig. 7b-l). Immunostaining indicated that the tumor was composed of highly heterogeneous cells with no specific differentiation traits. Therefore, the diagnosis of UPS was made with the exclusion of diseases such as epithelial malignant tumor, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, melanoma, atypical lymphoma, and other undifferentiated/unclassified sarcoma. Lymphatic and venous invasion of the tumor was observed, but no lymph node metastasis was found.

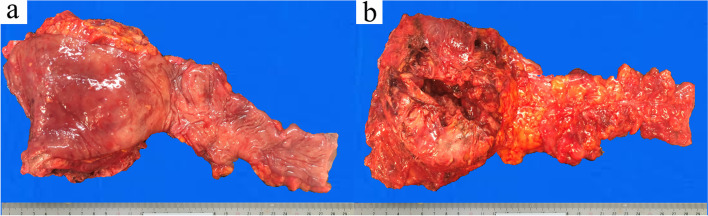

Fig. 5.

Macroscopic findings of the specimen. The mucosal aspect (a) and serous aspect (b) are presented. There was a 110 × 83 × 30 mm solid tumor with intraoperative damage and no obvious exposure to the mucosal surface

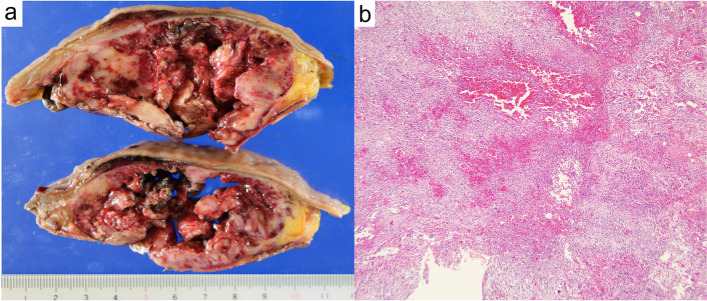

Fig. 6.

The cut surface of the tumor after fixation in formalin. The tumor consisted of a white solid with necrosis and hemorrhage in the center (a). Histopathologically, tumor cell growth was mainly observed in the muscularis propria to the subserosal layer of the rectum with inflammatory cell infiltration, hemorrhage, and necrotic tissue at the center (b, ×40 magnification).

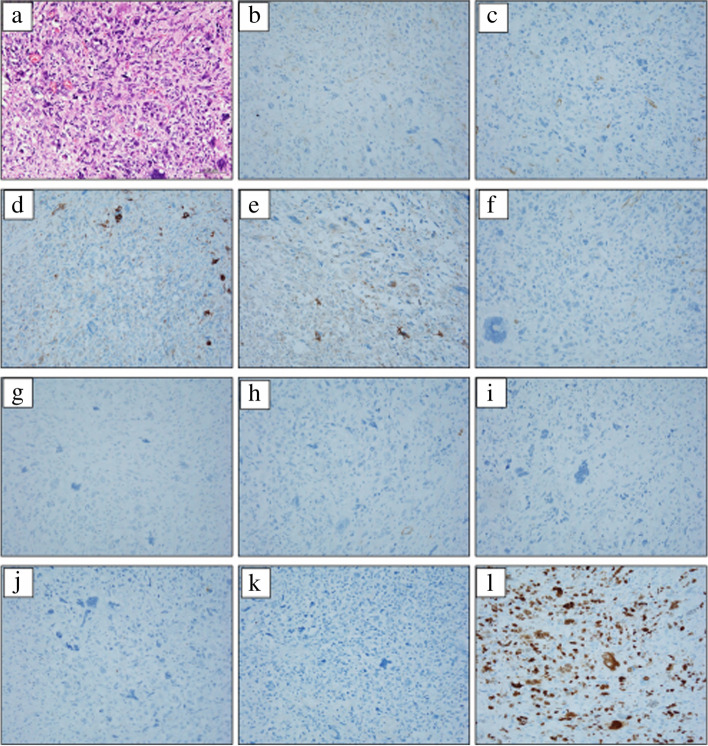

Fig. 7.

The histopathological findings and immunostaining. The tumor cells were composed of pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, and many typical and atypical mitotic figures were observed (a). On immunostaining, the tumor cells were focally positive for cluster of differentiation (CD) 117/KIT (b), α-smooth muscle actin (c), AE1/AE3 (d), and EMA (e) and negative for CD34 (f), DOG1 (g), h-caldesmon (h), desmin (i), S100 protein (j), and CD45 (k). Ki-67/MIB1 proliferation index was very high (l). (a ×100 magnification, b–l ×200 magnification)

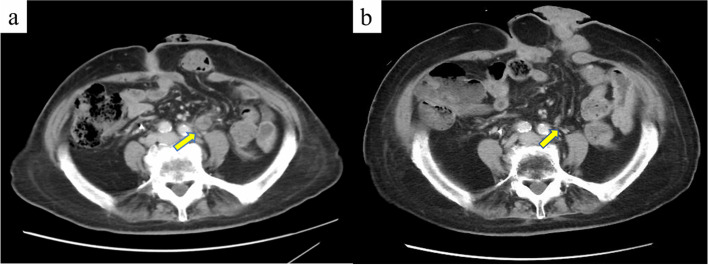

Contrast-enhanced CT performed 2 months after surgery showed bilateral pelvic lymph node enlargement and recurrence (Fig. 8a). Considering the patient’s age, we performed radiotherapy (50 Gy/25 Fr targeting the pelvic region). At present, 20 months have passed since the surgery, and 16 months have passed since the completion of radiotherapy. CT shows that the recurrent lymph nodes have disappeared, and no new distant metastasis has been observed (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows pelvic lymph node recurrence (a, indicated by an arrow). After radiotherapy, the metastatic lymph nodes disappeared (b, indicated by an arrow)

Discussion

UPS is a malignant soft tissue sarcoma (STS) that has been reclassified from MFH with the development of the pathological diagnosis. MFH was first documented as malignant histiocytoma and fibrous xanthoma by Ozello et al. in 1963 and was described as malignant fibrous xanthoma by O'Brien and Stout in the same group in the following year [3, 4]. In 1978, Weiss and Enzinger analyzed the clinicopathological features of 200 cases of MFH and established the concept of MFH. At that time, MFH was considered to be a malignant tumor derived from pleomorphic spindle cells that can differentiate into histiocytes and fibroblasts [2]. However, the accumulation of cases and pathological studies suggest that the histogenesis of MFH is undifferentiated mesenchymal cells. Furthermore, in recent years, STSs have been classified according to their tendency to differentiate, rather than the histogenesis. Therefore, the concept of MFH disappeared from the WHO disease classification in 2002 and 2013. In these WHO classifications, the major category of undifferentiated/unclassified sarcoma was created and further divided into five subtypes: undifferentiated round cell sarcoma, undifferentiated spindle cell sarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, undifferentiated epithelioid sarcoma, and undifferentiated sarcoma. MFH corresponds to the UPS [1]. UPS/MFH is frequently seen in individuals of 50–70 years of age, is more often seen in males, and is more frequent in Whites in comparison with Asians and Blacks. UPS/MFH occurs in the extremities and retroperitoneum, similarly to other soft tissue tumors, and rarely occurs in the gastrointestinal tract [5]. The clinical manifestations of colorectal UPS/MFH are nonspecific, and fever, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, weight loss, hemorrhage, and anorectal pain have been reported. The preoperative diagnosis of colorectal UPS/MFH is very challenging because of the rarity and variety of differential diseases [6]. CT images of UPS/MFH show it as a large soft tissue density mass that is relatively well-defined, segmental, and sometimes infiltrative. The center of the tumor frequently shows low attenuation, indicating necrosis, hemorrhage, and mucous degeneration [7]. MRI findings often demonstrate a heterogeneous signal on all sequences due to the various components. The solid components of the tumor exhibit enhancement after contrast agent administration [8].

The primary treatment for UPS is complete resection of the tumor, with the widest possible margins. Complete resection of the tumor has been reported to be closely related to the prognosis [9]. However, many STSs arising in the abdomen, including UPS, are very large and frequently invade vital organs at the time of the diagnosis. Therefore, the local recurrence rate and overall survival rate of STSs are inferior to those of extremity lesions because it is difficult to secure sufficient margins [10]. For UPS arising in the abdomen, it is more important to combine preoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy in comparison with UPS that occurs on the surface of the body. Preoperative treatment of UPS must be discussed comprehensively with other STSs because of the rarity of the disease and the relative newness of the disease concept. The benefits of preoperative radiotherapy are a reduction in tumor size, preservation of the adjacent organs, and reduction of the risk of local recurrence. Several large retrospective analyses have reported that preoperative radiotherapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma contributes to the control of local recurrence and the prognosis [11, 12]. On the other hand, randomized STRASS trials have shown no clear benefit of preoperative radiotherapy [13]. In each trial, liposarcomas accounted for the majority of soft tissue sarcomas enrolled, and UPS accounted for a small proportion. Therefore, the efficacy of preoperative radiotherapy for UPS has not been established, but it may be effective only if the indications are carefully considered. Preoperative chemotherapy for retroperitoneal sarcoma is also controversial. Retrospective studies have indicated that it may have an adverse effect on the prognosis, presumably because of the characteristics of sarcoma, which is associated with a high risk of local recurrence. At present, a prospective, randomized phase III trial (NCT04031677) is underway in high-risk retroperitoneal sarcomas, and the results are awaited [14]. Cytotoxic therapy consisting of doxorubicin and ifosfamide is recommended for unresectable STS with distant metastasis. Recent progress in the analysis of the molecular pathogenesis of the genome, the development of novel-targeted therapies, and the accumulation of cases have also clarified the treatment of each subtype of STS [15]. The multi-kinase inhibitor sunitinib has been reported to have some antitumor efficacy against previously treated UPS in a phase II study [16]. UPS showed the higher expression of genes related to antigen presentation and T-cell infiltration in comparison with other STSs. Therefore, meaningful responses to nivolumab-ipilimumab combination therapy and pembrolizumab therapy have been reported in pretreated UPS [17, 18]. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and radiotherapy for UPS that was refractory to conventional chemotherapy achieved complete response (CR) in a case report [19]. Currently, the effects of preoperative radiotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy on retroperitoneal UPS are being explored [20].

A search of PubMed revealed that 28 cases of MFH/UPS occurring in the colorectum and anus were reported in the relevant English literature. Including our case, a total of 29 cases were reviewed. The male to female ratio of incidence was 20:9. The average age of the patients was 58 years (12–85 years). It occurred in all sites of the colorectum and anus, and this was the eighth case in the anorectal region. All patients were symptomatic, and the most common symptoms were abdominal pain, abdominal mass, abdominal distension, bloody stool, and diarrhea. The median diameter of the tumor was 7.2 cm (1.7–19 cm). All cases were treated by surgery with the exception of one autopsy case. Almost all surgery was performed by laparotomy, probably due to the large size of the tumor at the diagnosis. Our case is the first report of laparoscopic surgery for MFH/UPS in the colorectum and anus. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered in 4 cases, adjuvant radiotherapy was administered in 3 cases, and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was administered in 1 case; however, no patients had received neoadjuvant therapy. Among the nine patients with local or distant recurrence, mortality was reported in all but our case (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of MFH/UPS in the colorectum and anus

| Author | Age | Sex | Site | Size (cm) | Symptom | Primary treatment | Adjuvant | Recurrence | Prognosis (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verma P. 1979 [21] | 38 | M | Rectum | 12 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 14 M |

| Sewell R. 1980 [22] | 74 | M | Transverse | 8.5 × 5 ×5 | Anorexia, diarrhea | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 12 M |

| Levinson M. M. 1981 [23] | 17 | M | Transverse, rectosigmoid | 10, 8.3 × 2 | Abdominal pain, fever | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | ND | ND |

| Waxman M. 1983 [24] | 52 | F | Sigmoid | 7.5 × 6 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | Yes (local) | Dead 9M |

| Rubbini M. 1983 [25] | 60 | M | Sigmoid | 7 | Bloody stool | Surgery (laparotomy) | Chemotherapy | Yes (liver, lymph node) | Dead 26 M |

| Spagnoli L. G. 1984 [26] | 52 | F | Anorectal | 2.6 × 1.6 × 1 | Bloody stool | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | Yes (lung, local) | Dead 24 M |

| Kukora J. S. 1985 [27] | 73 | M | Transverse | 2.5 × 2 | Abdominal pain, constipation | Surgery (laparotomy) | ND | No | Alive 48 M |

| Baratz M. 1986 [28] | 73 | M | Transverse | 15 × 7 × 4, 8 × 4 × 1 | Anorexia, anemia | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 6 M |

| Satake T. 1988 [29] | 62 | M | Ascending, transverse | 17 × 10 × 8, 19 × 7 × 7 | Abdominal mass | No (autopsy) | ND | ND | ND |

| Flood H. D. 1989 [30] | 41 | M | Anal canal | 6 | Abdominal mass | Surgery (laparotomy) | Radiotherapy | No | Alive 16 M |

| Katz R. N. 1990 [31] | 62 | F | Cecum | 2 × 1.8 × 1.1 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 3 M |

| Murata I. 1993 [32] | 50 | M | Ascending | 9.65 × 6.0 × 5.0 | Abdominal distention, anorexia | Surgery (laparotomy) | Chemotherapy | No | Alive 10 M |

| Huang Z. 1993 [33] | 12 | M | Ascending | 3.5 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 16 M |

| Makino M. 1994 [34] | 72 | M | Transverse | 7.5 × 5.0 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | Yes (peritoneum) | Dead 4 M |

| Hiraoka N. 1997 [35] | 64 | M | Cecum | 4 × 5 × 3 | Abdominal distention | Surgery (laparotomy) | Chemotherapy | Yes (lymph node) | Dead 4 M |

| Kawashima H. 1997 [36] | 50 | F | Descending | 4 × 3.2 | Abdominal pain, diarrhea | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 84 M |

| Udaka T. 1999 [37] | 47 | M | Ascending | 7 × 5 × 4 | Abdominal mass | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 13 M |

| Singh D. R. 1999 [38] | 55 | M | Rectum | 4 × 2.5 | Tenesmus, perineal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | Chemoradiotherapy | No | Alive 46 M |

| Okubo H. 2005 [39] | 66 | M | Ascending | 14.5 × 8.0 × 4.5 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 33 M |

| Gupta C. 2006 [40] | 46 | F | Cecum, ascending | 17 | Abdominal distention, anorexia | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 36 M |

| Fu D. L. 2007 [41] | 70 | M | Cecum | 12 × 10 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | Yes (lung) | Dead 1 M |

| Bosmans B. 2007 [42] | 73 | M | Sigmoid | 3.2 | Anemia | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 22 M |

| Kim B. G. 2008 [43] | 63 | F | Anal canal | 1.7 × 1.3 × 0.3 | Bloody stool, anal mass | Surgery (TAE) | Radiotherapy | No | Alive 15 M |

| Azizi R. 2011 [44] | 80 | M | Rectum | 5 × 4 × 2.5 | Rectal bleeding | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | ND | ND |

| Wang YJ 2012 [45] | 55 | M | Sigmoid | 6 | Abdominal pain | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | Yes (local) | Dead 5 M |

| Ji W. 2016 [46] | 68 | F | Ascending | 8 × 6 | Fever | Surgery (laparotomy) | Radiotherapy | Yes (local) | Dead 60 M |

| Kazama 2019 [47] | 50 | M | Ascending | 7.2 × 6.0 | Abdominal pain, numbness | Surgery (laparotomy) | Chemotherapy | No | Alive 6 M |

| Han X. 2022 [48] | 65 | F | Descending | 10 × 8 × 5 | Fever, fatigue | Surgery (laparotomy) | No | No | Alive 12 M |

| Our case 2022 | 85 | F | Rectum | 11 × 8.3 × 3 | Anal pain | Surgery (laparoscopy) | No | Yes (lymph node) | Alive 12 M |

MFH malignant fibrous histiocytoma, UPS undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, ND not described

In our case, the resection of other pelvic organs should have been considered to achieve complete resection of the tumor. However, extended surgery is controversial because it is expected to impair quality of life. Preoperative treatment could have been considered if the pathological diagnosis had been obtained preoperatively. With the accumulation of evidence, preoperative treatment with a combination of radiotherapy, cytotoxic chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and molecular targeted agents may be performed in cases similar to ours.

Conclusions

We reported a case of UPS arising in the rectum. The surgical procedure for UPS should be carefully selected because complete removal of the tumor is desirable. Indications for preoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy should also be considered.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all people involved in this work.

Abbreviations

- UPS

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma

- MFH

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

- WHO

World Health Organization

- CT

Computed tomography

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- STS

Soft tissue sarcoma

Authors’ contributions

KK wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. MH revised the manuscript. KE supervised the writing of the manuscript. ST, SH, MK, RH, TI, MI, and MO discussed the content of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

We have obtained consent to publish from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Keita Kodera, Email: keitakodera1001@jikei.ac.jp.

Masato Hoshino, Email: h-masato@jikei.ac.jp.

Sumika Takahashi, Email: sumika1124@jikei.ac.jp.

Suguru Hidaka, Email: suguru.0925@gmail.com.

Momoko Kogo, Email: niente0pesca@gmail.com.

Ryosuke Hashizume, Email: hashihide@jikei.ac.jp.

Tomonori Imakita, Email: imakita0626@gmail.com.

Mamoru Ishiyama, Email: mamoru.mamoru@hotmail.co.jp.

Masaichi Ogawa, Email: masatchmo1962@yahoo.co.jp.

Ken Eto, Email: etoken@jikei.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: an analysis of 200 cases. Cancer. 1978;41:2250–2266. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2250::AID-CNCR2820410626>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozzello L, Stout AP, Murray MR. Cultural characteristics of malignant histiocytomas and fibrous xanthomas. Cancer. 1963;16:331–344. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196303)16:3<331::AID-CNCR2820160307>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien JE, Stout AP. Malignant fibrous xanthomas. Cancer. 1964;17:1445–1455. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196411)17:11<1445::AID-CNCR2820171112>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldblum JR. An approach to pleomorphic sarcomas: can we subclassify, and does it matter? Mod Pathol. 2014;27(Suppl 1):39–46. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, Kang DB, Park WC. Primary undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the colon mesentery. Ann Coloproctol. 2019;35:152–154. doi: 10.3393/ac.2018.03.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy AD, Manning MA, Miettinen MM. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the abdomen and pelvis: radiologic-pathologic features, part2-uncommon sarcomas. Radiographics. 2017;37:797–812. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Li Y, Zhao Y, Qiao J. CT and MRI of superficial solid tumors. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8:232–251. doi: 10.21037/qims.2018.03.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen S, Huang W, Luo P, Cai W, Yang L, Sun Z, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: long-term follow-up from a large institution. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10001–10009. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S226896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roeder F. Radiation therapy in adult soft tissue sarcoma-current knowledge and future directions: a review and expert opinion. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:3242. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toulmonde M, Bonvalot S, Meeus P, Stoeckle E, Riou O, Isambert N, et al. Retroperitoneal sarcomas: patterns of care at diagnosis, prognostic factors and focus on main histological subtypes: a multicenter analysis of the French sarcoma group. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25:735–742. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nussbaum DP, Rushing CN, Lane WO, Cardona DM, Kirsch DG, Peterson BL. Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy versus surgery alone for retroperitoneal sarcoma: a case-control, propensity score-matched analysis of a nationwide clinical oncology database. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:966–975. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30050-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonvalot S, Gronchi A, Le Pechoux C, Swallow CJ, Strauss D, Meeus P, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for patients with primary retroperitoneal sarcoma (EORTC-62092: STRASS): a multicenter, open-label, randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1366–1377. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma SJ, Oladeru OT, Farrugia MK, Shekher R, Iovoli AJ, Singh AK. Evaluation of preoperative chemotherapy or radiation and overall survival in patients with nonmetastatic, resectable retroperitoneal sarcoma. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025529. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolle MA, Szkandera J, Andreou D, Palmerini E, Bergovec M, Leithner A. Treatment options in unresectable soft tissue and bone sarcoma of the extremities and pelvis - a systematic literature review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:799–814. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.200069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmood ST, Agresta S, Vigil CE, Zhao X, Han G, D'Amato G, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib malate, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with relapsed or refractory soft tissue sarcomas. Focus on three prevalent histologies: leiomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:1963–1969. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Angelo SP, Mahoney MR, Tine BAV, Atkins J, Milhem MM, Jahagirdar BN, et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): two open-label, non-comparative, randomized, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:416–426. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tawbi HA, Burgess M, Bolejack V, Tine BAV, Schuetze SM, Hu J, et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): a multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1493–1501. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30624-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guram K, Nunez M, Einck J, Mell LK, Cohen E, Sanders PD, et al. Radiation therapy combined with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy for metastatic undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma of the maxillary sinus with a complete response. Front Oncol. 2018;8:435. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keung EZ, Lazar AJ, Torres KE, Wang WL, Cormier JN, Guadagnolo BA, et al. Phase II study of neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade in patients with surgically resectable undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:913. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verma P, Chandra U, Bhatia PS. Malignant histiocytoma of the rectum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF02586815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sewell R, Levine BA, Harrison GK, Tio F, Schwesinger WH. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the intestine: intussusception of a rare neoplasm. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:198–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02587627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levinson MM, Tsang D. Multicentric malignant fibrous histiocytomas of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1982;25:327–331. doi: 10.1007/BF02553607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waxman M, Faegenburg D, Waxman JS, Janelli DE. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon associated with diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:339–343. doi: 10.1007/BF02561712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubbini M, Marzola A, Spanedda R, Scalco GB, Zamboni P, Guerrera C, et al. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the sigmoid colon: a case report. Ital J Surg Sci. 1983;13:299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spagnoli LG, Dell'Isola C, Sportelli G, Mauriello A, Rizzo F, Casciani CU. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of storiform-pleomorphic type: a case report of an ano-rectal localization. Tumori. 1984;70:567–570. doi: 10.1177/030089168407000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kukora JS, Bagnato J, Gatling R, Maher JW. Fibrous histiocytoma of colon and pancreas. Dig Surg. 1985;2:180–184. doi: 10.1159/000171701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baratz M, Ostrzega N, Michowitz M, Messe G. Primary inflammatory malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1986;29:462–465. doi: 10.1007/BF02561588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Satake T, Matsuyama M. Cytologic features of ascites in malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1988;38:921–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1988.tb02363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flood HD, Salman AA. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the anal canal. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:256–259. doi: 10.1007/BF02554541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz RN, Waye JD, Batzel EL, Reiner MA, Freed JS. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the gastrointestinal tract in a patient with neurofibromatosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1527–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murata I, Makiyama K, Miyazaki K, Kawamoto AS, Yoshida N, Muta K, et al. A case of inflammatory malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1993;28:554–563. doi: 10.1007/BF02776955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang Z, Wei K. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the ascending colon in a child. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:972–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makino M, Kimura O, Kaibara N. Radiation-induced malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the transverse colon: case report and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:767–771. doi: 10.1007/BF02349285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiraoka N, Mukai M, Suzuki M, Maeda K, Nakajima K, Hashimoto M, et al. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the cecum: report of a case and review of the literature. Pathol Int. 1997;47:718–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1997.tb04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawashima H, Ikeue S, Takahashi Y, Kashiyama M, Hara T, Yamazaki S, et al. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the descending colon. Surg Today. 1997;27:851–854. doi: 10.1007/BF02385277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Udaka T, Suzuki Y, Kimura H, Miyashita K, Suwaki T, Yoshino T. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the ascending colon: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:160–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02482242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh DR, Aryya NC, Sahi UP, Shukla VK. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the rectum. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:447–448. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okubo H, Ozeki K, Tanaka T, Matsuo T, Mochinaga N. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the ascending colon: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005;35:323–327. doi: 10.1007/s00595-004-2915-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta C, Malani AK. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu DL, Yang F, Maskay A, Long J, Jin C, Yu XJ, et al. Primary intestinal malignant fibrous histiocytoma: two case reports. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1299–1302. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i8.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bosmans B, Graaf EJR, Torenbeek R, Tetteroo GWM. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the sigmoid: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:549–552. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim BG, Chang IT, Park JS, Choi YS, Kim GH, Park ES, Choi CH. Transanal excision of a malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the anal canal: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1459–1462. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Azizi R, Mahjoubi B, Shayanfar N, Anaraki F, Shoolami LZ. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma of rectum: report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:111–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang YJ, Tang SS, Zhao Y. Contrast-enhanced sonographic appearance of malignant fibrous histiocytoma in the sigmoid colon: a case report. J Clin Ultrasound. 2012;40:439–442. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ji W, Zhong M, You Y, Hu KE, Wu B. Primary malignant fibrous histiocytoma of the colon: a case report and review of the literature. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:1006–1008. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kazama S, Gokita T, Takano M, Ishikawa A, Nishimura Y, Ishii H, et al. G-CSF-producing undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma adjacent to the ascending colon and in the right iliopsoas muscle: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2019;58:2783–2789. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.2762-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Han X, Zhao L, Mu Y, Liu G, Zhao G, He H, et al. Undifferentiated high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma of the colon: a rare case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:115. doi: 10.1186/s12876-022-02189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.