Abstract

Aim

Develop a robust and user-friendly software tool for the prediction of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (RO) in patients with schizophrenia treated with either olanzapine or risperidone, in order to facilitate clinician exploration of the impact of treatment strategies on RO using sparse plasma concentration measurements.

Methods

Previously developed population pharmacokinetic (PPK) models for olanzapine and risperidone were combined with a pharmacodynamic (PD) model for D2 RO and implemented in the R programming language. Maximum a posteriori (MAP) Bayesian estimation was used to provide predictions of plasma concentration and RO based on sparse concentration sampling. These predictions were then compared to observed plasma concentration and RO.

Results

The average (standard deviation) response times of the tools, defined as the time required for the application to predict parameter values and display the output, were 2.8 (3.1) and 5.3 (4.3) seconds for olanzapine and risperidone, respectively. The mean error (95% confidence interval) and root mean squared error (RMSE, 95% CI) of predicted versus observed concentrations were 3.73 ng/mL (−2.42 – 9.87) and 10.816 ng/mL (6.71 – 14.93) for olanzapine, and 0.46 ng/mL (−4.56 – 5.47) and 6.68 ng/mL (3.57 – 9.78) for risperidone and its active metabolite (9-OH risperidone). Mean error and RMSE of RO were −1.47% (−4.65 – 1.69) and 5.80% (3.89 – 7.72) for olanzapine and −0.91% (−7.68 – 5.85) and 8.87% (4.56 – 13.17) for risperidone.

Conclusion

Our monitoring software predicts concentration-time profiles and the corresponding D2 RO from sparsely-sampled concentration measurements in an accessible and accurate form.

Keywords: Olanzapine, risperidone, population pharmacokinetic model, target concentration intervention

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a psychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of roughly 0.5-1% of the population worldwide, with similar rates amongst males and females [1]. Onset of the disease typically occurs during early adulthood and generally requires maintenance antipsychotic therapy throughout the lifetime of the patient [2]. While the etiology of the disease is not completely understood, the current consensus suggests an abnormally excessive dopaminergic activity in the striatum [3] in a subset of patients [4].

The treatment of schizophrenia poses a challenge to clinicians as poor clinical outcomes can arise both from under- and over-treatment. In the former scenario, patients receiving a subtherapeutic dose will continue to experience psychotic symptoms assumed to be due to insufficient striatal dopamine D2 receptor occupancy (RO) . In the latter scenario, patients receiving a supratherapeutic dose may experience extrapyramidal adverse events from excessive RO [5]. Positron emission tomography (PET) studies have identified a link between striatal dopamine D2 RO and successful clinical outcomes, with a therapeutic window identified as 65 - 80% D2 RO [6,7]: RO below 65% is associated with poor symptomatic response and RO above 80% is associated with extrapyramidal side effects as a result of excessive receptor antagonism. However, due to challenges associated with availability and high cost, it is not feasible to routinely measure RO with PET in clinical settings. Thus, antipsychotics are titrated based on clinical effectiveness and tolerability on a trial-and-error basis, leading to suboptimal clinical outcomes [8,9].

Previous studies have described the relationship between plasma concentrations of several antipsychotics and dopamine D2 RO by use of the Hill equation, drug-specific maximal binding values, and dissociation rate constant parameters for each drug [7,10]. These models allow prediction of RO from assayed plasma concentrations, potentially reducing the need for PET scans.

Olanzapine and risperidone are commonly used antipsychotics indicated for the treatment of schizophrenia [11]. Both antipsychotics act as antagonists of dopamine D2 receptors [12]. This antagonism of dopamine activity is required for their efficacy, but it is also responsible for various side effects. The pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of olanzapine and risperidone have been well characterized. Population PK (PPK) models exist for both drugs [13,14]. PPK modeling is a mathematical framework that can identify the central tendencies of PK parameters in a population, the variability in those parameters across individuals, and the sources of the variability [15]. PPK models can be used to generate individual estimates of PK parameters based on a patient’s demographics and sparsely sampled plasma drug concentrations. Maximum-a-posteriori Bayesian estimation maximizes the likelihood of predicting an individual’s PK parameters given their observed sparsely-sampled drug concentrations and demographics, while taking into account the prior distribution of population parameters. With these individual parameters, one can use the model to predict doses to achieve target drug concentrations. Combined with pharmacodynamic models that relate plasma concentrations to D2 RO, these PPK models can be used to predict RO with various dosages and to determine the optimal dosage for an individual patient. The presence of a well-defined therapeutic window for RO and the ability to reliably predict RO in a patient make these two drugs excellent candidates for model guided dosage optimization.

Nakajima et. al. have shown that the population modeling approach, using the nonlinear mixed effects modeling program NONMEM, was able to adequately predict RO [16]. However, although considered the gold standard for population modeling, NONMEM is difficult to use at the point of care by clinicians. NONMEM requires specialized training to execute, is expensive, and is inconvenient to use in the clinic due to the lack of a graphical user interface. Thus, the objective of the current work was to extend on the approach of Nakajima et. al. by developing and validating a convenient, yet robust and accurate, software tool allowing physicians to explore different levels of RO using sparse blood concentration measurements of olanzapine or risperidone. This tool can facilitate the investigation of optimal dosage strategies. An ancillary, but important goal, is for said tool to be accessible and readily usable in a clinical trial setting. To accomplish this, the tool has been implemented using free, open-source software.

2. Methods

All drug and molecular target names referenced in this manuscript conform to IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY nomenclature classification [17].

2.1. Settings and Participants

The details of the study have been previously reported [18,19]. In brief, PET imaging was carried out at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Toronto, between August 2007 and July 2013. The participants were recruited among clinically stable outpatients aged 50 or older who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and who had received a continuous olanzapine dosage of at least 10 mg/day or a risperidone dosage of at least 2 mg/day. In total, data from 32 participants was used in the analysis: 20 receiving olanzapine and 12 receiving risperidone. The study was approved by the CAMH Research Ethics Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Study Design

As previously described, blood samples from 2 separate time points were measured for plasma concentrations of either olanzapine or risperidone with its active metabolite (9-hydroxy risperidone: 9-OH risperidone). The lower limits of quantitation were 2.3 ng/mL for olanzapine, 1.0 ng/mL for risperidone, and 2.1 ng/mL for 9-OH risperidone. Typical assay precisions were (%CV) 5.3 – 8.2% for olanzapine, 6.1 – 6.6% for risperidone, and 3.1 – 10.5% for 9-OH risperidone [16]. Daily dosage of olanzapine or risperidone was then reduced by up to 40%, while ensuring that the dosage was above the lowest dose recommended in clinical guidelines, specifically 7.5 mg/day for olanzapine and 1.5 mg/day for risperidone. Participants underwent a [11C]-raclopride PET scan prior to dose reduction and a minimum of two weeks after dosage reduction, at which point an additional blood sample was taken. Plasma concentrations of olanzapine, risperidone, and 9-hydroxyrisperidone were quantified by tandem LC/MS/MS using analytical methods developed by the CAMH Clinical Laboratory [16].

2.3. Olanzapine and Risperidone Population Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Models

Population pharmacokinetic models have previously been developed for olanzapine and risperidone [13,14]. To summarize, 1527 olanzapine concentrations from 523 patients and 1236 risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone concentrations from 490 patients were used for the respective analyses. The best fitting models, using goodness-of-fit plots and objective function values as selection criteria, were a one compartment model with first order absorption for olanzapine and a one-compartment, parent-metabolite model with first order absorption for risperidone and its active metabolite. Risperidone clearance was found to be most adequately described by a tri-modal mixture distribution, likely arising from differing phenotypes (extensive, intermediate, and poor metabolizers) of the CYP2D6 enzyme, although genotyping was not performed. Smoking status, race, and sex were found to be significant covariates of olanzapine drug clearance and age was found to be a significant covariate of 9-OH risperidone clearance. The effects of smoking status, race (Black/African American vs not Black/African American), and sex on olanzapine clearance were modeled using the following additive relationship:

where TVCLcov is the population mean of clearance when covariate effects are incorporated, TVCL is the mean clearance value for the entire population, CLSmoke, CLRace, and CLSex are the estimated fixed effects due to smoking status, race, and sex, respectively, and COVSmoke, COVRace, and COVSex indicate an individual’s smoking status (1 for smokers, 0 for nonsmokers), race (1 for Black/African American, 0 for not Black/African American), and sex (1 for males, 0 for females), respectively. The effect of age on the clearance of 9-OH risperidone was modeled using a centered exponential relationship:

where TVCLMcov is the clearance of 9-OH risperidone (CLM) when covariate effects are incorporated, TVCLM is the mean CLM for the entire population, CLMAge is the fixed effect of age on CLM, Age is the age of the individual, and Ageref is a reference value for Age, set to a nominal value that approximates the population median age, in this case set to 50 years old.

All PK parameters were assumed to follow a log-normal distribution. An individual’s parameter values can be described as follows:

where Pik is the kth parameter in the ith individual, TVPk is the population mean of the kth parameter, and ɳik represents the difference between the natural log of the individual’s parameter value and the natural log of TVPk, and comes from a normal distribution with mean 0 and variance Ωk.

For olanzapine, the most appropriate residual error model was found to be an additive error model. For risperidone and its active metabolite, an additive plus proportional error model was used.

A previously published study describes the pharmacodynamic relationships between a variety of antipsychotic drugs and dopamine D2 RO [10]. Briefly, the study pooled literature data from studies reporting plasma concentration data of antipsychotic drugs and the corresponding RO data. RO data was derived from PET scans primarily through use of the simplified reference tissue model (SRTM) [20]. The concentration-RO relationships were modeled using a one-site binding model of the form:

where Emax is the maximum receptor occupancy due to a given drug, Cplasma is the concentration of drug in plasma, and EC50 is the drug concentration associated with 50% of the maximum receptor occupancy. In the case of risperidone, Cplasma and EC50 refer to the combined concentration of risperidone plus 9-OH risperidone.

The previously developed olanzapine and risperidone population PK models were fitted using plasma concentration measurements from the CATIE study. This analysis was performed in NONMEM version 7.3.0. The olanzapine model was implemented using the subroutine ADVAN2 TRANS2 (1-compartment model with first-order absorption) while risperidone was implemented using ADVAN5 (general linear kinetics model). Both models were evaluated using first-order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCE-I). Plasma concentrations and ROs measured during the CAMH PET study were then used to validate the models and compare the predictive performance of the Shiny app to that of NONMEM.

2.4. Dose Optimization and Companion Tools

2.4.1. Estimating Maximum A Posteriori (MAP) Bayes Parameters

Bayes theorem is fundamentally important in obtaining individual estimates of PK parameters in the context of population modeling. Using the theorem, the likelihood of an individual’s PK parameter random effect (ɳ) values given their observed concentrations can be derived:

where ɳ represents the vector of all ɳk for an individual, D represents the observed data for a participant, and C is a constant. The probability of an individual’s random effect parameters given their observed data is proportional to the probability of the observed data given a set of random effect parameters multiplied by the probability of the set of random effects. After some manipulation and simplification, we obtain the MAP Bayes objective function that we seek to minimize by optimizing the participant’s parameters:

where yobs,j is the jth observed concentration, ypred, j is the jth model predicted observation, σ2j is the variance associated with the jth predicted concentration, and m is the number of observed concentrations for an individual. In the case of risperidone, rather than using an explicit MIX subroutine for the mixture distribution on clearance as one would in NONMEM, in the Bayesian method we evaluate the objective function with all three population clearance values (poor metabolizer, intermediate metabolizer, and extensive metabolizer), then select the clearance value that results in the best likelihood.

2.4.2. Analysis Platform

R programming version 3.3.1 [21] was used for implementing the PPK model, optimizing parameters, and user interface design and functionality. R package mrgsolve version 0.8.6 [22] was used to solve model differential equations. The package implements a modified version of the Livermore Solver for Ordinary Differential Equations known as LSODA [23].

Gradient descent was used to optimize parameters from the optim R package. This function utilizes the quasi-newton method, which updates parameters using the inverse Hessian matrix to determine the direction of parameter search and the gradient of the objective function with respect to the parameters.

2.4.3. Search for Parameters

The search for parameters is an iterative process and can be described as follows:

Initially set all PK parameters to the population mean values by setting all ETAs to 0.

Simulate concentration-time profiles using the PK model.

Obtain vector of predicted concentrations at times in which concentrations were measured and calculate objective function value.

Use gradient descent optimization function to update ETA parameter values.

Return to step 2 and repeat process until convergence (no improvement in objective function)

2.4.4. Development of User Interface

The user interface for the application was developed using the R programming package, shiny [24]. This package allows for the creation of an HTML web application that can run R functions in the background. Input elements, known as control widgets, are included in the user interface which the clinical researcher can interact with. These inputs are then sent into the population pharmacokinetic model, parameter optimization is performed in R, and results are sent back to the user interface for the clinical researcher to review and to inform dosing. The application is open-source and can be downloaded from https://github.com/TomStraubinger/Olanz-Risp-App.

2.4.5. Application Workflow – Treatment Naïve

The application is divided into two major sections. The first section can be used to guide dosing in treatment naive patients using population mean parameters. The clinician can select to either simulate for a specific dosage, target a steady state trough concentration, or target a steady-state percent D2 RO. After specifying the dosing frequency in hours and pertinent patient characteristics described in section 2.3, the program displays the predicted pharmacokinetic and RO profiles in separate tabs. An example of the user interface for the olanzapine application is shown in Figure 1. If the clinician has selected to target a concentration or RO, the program will display a suggested dosage to achieve this level. Under the “Parameters” tab, the user can view population clearance and volume parameters, as well as exposure parameters such as AUC, peak, and trough concentrations.

Figure 1.

User interface of the olanzapine application initial dosing. This dashboard can be used to simulate dosing regimens or target specific exposures in treatment naïve patients with specific patient characteristics found to influence the PK of olanzapine (sex, race, and smoking status).

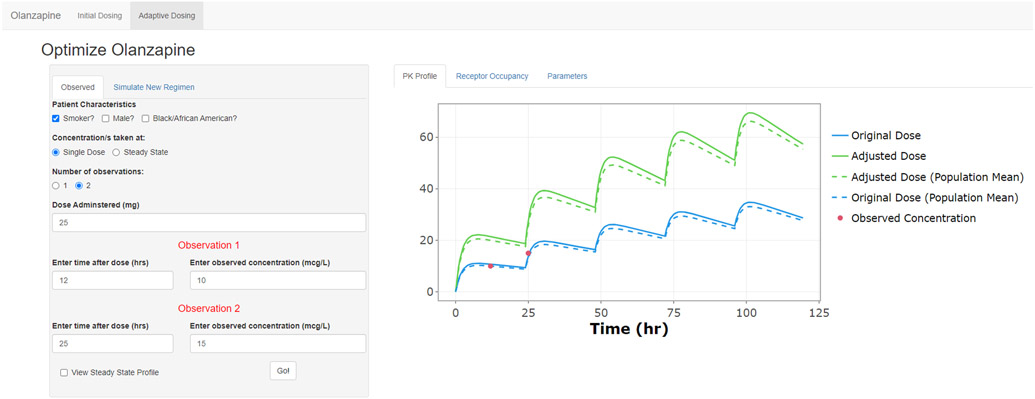

2.4.6. Application Workflow – Adaptive Dosing

While the first screen uses population mean PK parameters to make predictions, the second screen, shown in Figure 2, allows the clinician to fit the pharmacokinetic model to a patient’s observed plasma drug concentrations and obtain individual PK parameter estimates. Again, in this section, clinicians must enter pertinent patient demographics. However, they must also provide some information about plasma concentration measurements. Based on the model’s ability to utilize sparse sampling data, the user can provide one or two plasma drug concentration measurements, must specify whether the measurements were taken at steady state or after a single dose, and how long after the last dose each observation was taken. Once the observed data are entered, the program applies the population model to the individual’s data and generates empirical Bayes pharmacokinetic parameter estimates. The optimized parameter values can be viewed under the “Parameters” tab. Under the “New Regimen” tab, the clinician can now optimize dosing with these new parameters. Again, a specific dose can be simulated, or a steady-state trough concentration, or RO can be targeted, and the dosage will be suggested. The output plot under the “PK Profile” tab shows the predicted concentration vs. time profiles of the original regimen and the adjusted regimen, overlaid with the raw observed data. Under the “Receptor Occupancy” tab, the clinician can view the predicted RO profiles for the original and adjusted regimens.

Figure 2.

User interface of the olanzapine application adaptive dosing. Inputs are available for measured plasma concentrations taken at steady state of after a single dose. Displayed in the plot area are the original regimen (blue), observed plasma concentration/s (red), and predicted profile for regimen with adjusted dosage (green).

2.4.7. Evaluation of Performance and Statistical Analyses

Each participant had 3 blood samples collected at separate time points for either olanzapine or risperidone and its metabolite, 9-hydroxyrisperidone. For each participant, the concentrations from the first 2 time points were used in optimizing the individual’s parameter values. The third blood sample was used for external validation. External validation of a model allows for the qualification of the model’s predictive performance using data that were not used to fit the model. Additionally, since participants had a dosage reduction of 40% or less after the second blood sample time point, external validation allows for assessment of model performance for the prediction of receptor occupancy and plasma concentration when extrapolating to new dosage regimens.

Statistical analyses were performed using R. The following analyses were performed for predicted concentrations and D2 RO for both olanzapine and risperidone. To assess model performance in a quantitative manner, the mean prediction error (difference of predicted values and observed values) was used to detect the presence of any systemic bias in the model predictions. The mean root squared error (RMSE) was used as a measure of the model’s precision. A two-tailed Pearson’s correlation (r) analysis at an alpha level of 0.05 was performed to test the null hypothesis, H-null: r = 0, and the alternate hypothesis H-a: r ≠ 0. The mixture distribution for risperidone clearance was addressed in the analysis by evaluating the likelihood of the random effect at each of the three modes with respect to the clearance of risperidone. The optimal likelihood value resulting from this evaluation was then used as the basis for selecting the “population-mode” for clearance of risperidone out of the three possible models.

2.5. Nomenclature of Targets and Ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 [25].

3. Results

3.1. Application Speed

The developed applications were fast performing, taking an average (standard deviation) of 2.8 (3.1) and 5.3 (4.3) seconds for olanzapine and risperidone, respectively, to optimize the individual parameter values, simulate the concentration-time RO-time profiles, output final parameter values, and render a plot of the concentration-time profile for an individual. The slightly slower performance of the risperidone model is due to the higher complexity of this model.

3.2. Predictive Performance

The mean error (95% CI) of predicted versus observed olanzapine plasma concentrations was 3.73 ng/mL (−2.42 – 9.87). The RMSE (95%CI) of olanzapine plasma concentrations was 10.82 (6.71-14.93). The mean error of predicted versus observed D2 RO (95% CI) following treatment with olanzapine was −1.47% (−4.65 – 1.69) and the RMSE (95% CI) was 5.80 (3.89 – 7.72).

The mean error (95% CI) of predicted versus observed risperidone plus 9-OH risperidone plasma concentrations was 0.46 ng/mL (−4.56 – 5.47), and the RMSE (95%CI) was 6.68 (3.57 – 9.78). The mean error of predicted versus observed D2 RO (95% CI) following treatment with risperidone was −0.91% (−7.68 – 5.85) and the RMSE (95% CI) was 8.87 (4.56 – 13.17).

Visual comparisons of the predicted versus observed values for the concentration of both drugs are shown in Figure 3. Similarly, comparisons of observed versus predicted D2 RO are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the observed and predicted plasma concentrations of olanzapine (left) and risperidone + 9-OH risperidone (right) in patients receiving either olanzapine (n=20) or risperidone (n = 12).

Figure 4.

Relationship between the observed and predicted D2 receptor occupancy in patients receiving either olanzapine (n=20) or risperidone (n = 12).

Performance of the application was compared to results from Nakajima et. al., in which NONMEM was used to predict plasma concentrations and D2 RO at a third time point based on two sparsely-sampled plasma concentration measurements. Mean and standard deviation (SD) of plasma concentrations, dosages, and D2 RO are reported in Table 1. A summary of the predicted population pharmacokinetic parameters used in the model can be found in Table 2. The comparison between the application and the published predictions using NONMEM is summarized in Table 3 and Table 4, and suggests that the bias and precision of the application are comparable to that of NONMEM.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for observed dose, concentration, and D2 receptor occupancy.

| Parameter | Units | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | Dose | mg | 14.56 | 8.23 |

| Concentration | ng/mL | 36.01 | 29.52 | |

| D2 Receptor Occupancy | % | 65.65 | 24.03 | |

| Risperidone | Dose | mg | 3.26 | 2.02 |

| Concentration | ng/mL | 4.31 | 5.60 | |

| 9-OH Risperidone | Concentration | ng/mL | 32.33 | 21.06 |

| Risperidone + 9-OH Risperidone | Concentration | ng/mL | 34.23 | 22.88 |

| D2 Receptor Occupancy | % | 65.39 | 12.16 |

Table 2.

Summary of population PK parameter values. CL, clearance of olanzapine or risperidone; ka, first-order absorption rate constant; V, volume of distribution of olanzapine or risperidone; VM, volume of distribution of 9-OH risperidone; CLM, clearance of 9-OH risperidone; KF, fraction of risperidone clearance to 9-OH risperidone; ω, inter-individual variability coefficient for the corresponding parameter; Emax, maximum drug effect; EC50, drug concentration producing 50% of maximum effect; PM, poor metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; EM, extensive metabolizer [13,14].

| Parameter | Units | Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | CL | L/h | 16.2 |

| ka | h−1 | 0.5 | |

| V | L | 2230 | |

| Smoking on CL | 8.74 | ||

| Sex on CL | 5.14 | ||

| Race on CL | 4.28 | ||

| ωCL | % CV | 46.04 | |

| ωV | % CV | 72.66 | |

| Emax | % Occupancy | 100 | |

| EC50 | ng/mL | 10.4 | |

| Risperidone | CLPM | L/h | 13.7 |

| CLIM | L/h | 77.7 | |

| CLEM | L/h | 158 | |

| V, VM | L | 444 | |

| ka | h−1 | 1.7 | |

| CLM | L/h | 8.83 | |

| Age on CLM | −0.378 | ||

| KFPM | 0.96 | ||

| KFIM | 1.0 | ||

| KFEM | 0.595 | ||

| ωCL, PM | % CV | 59.16 | |

| ωCL, IM | % CV | 51.96 | |

| ωCL, EM | % CV | 62.45 | |

| ωV | % CV | 54.77 | |

| ωCLM | % CV | 73.45 | |

| Emax | % Occupancy | 88 | |

| EC50 | ng/mL | 8.2 |

Table 3.

A comparison of the predictive performance between the R-based Shiny application optimization and NONMEM for olanzapine or risperidone plasma concentrations.

| Shiny Dashboard Application |

NONMEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | Mean error (ng/mL) | 3.73 | 3.23 |

| Root mean squared error (ng/mL) | 10.80 | 13.96 | |

| Risperidone | Mean error (ng/mL) | 0.46 | 3.23 |

| Root mean squared error (ng/mL) | 6.68 | 9.30 |

Table 4.

A comparison of the predictive performance between the R-based Shiny application optimization and NONMEM for D2 receptor occupancy (%) following administration of olanzapine or risperidone.

| Shiny Dashboard Application |

NONMEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | Mean error (RO %) | −1.47 | −1.76 |

| Root mean squared error (RO %) | 5.80 | 7.21 | |

| Risperidone | Mean error (RO %) | 0.91 | 0.64 |

| Root mean squared error (RO %) | 8.87 | 10.40 |

4. Discussion

Previous work has identified a putative therapeutic range of D2 RO for the treatment of schizophrenia with olanzapine or risperidone. The establishment of a therapeutic window, in theory, allows for dosage adjustment based on a target drug concentration, an approach known as target concentration intervention (TCI), which could be superior to the current trial and error approach. However, TCI presents its own challenges. The logistics and costs associated with repeated blood sampling needed for TCI makes it impractical in most clinical settings. Furthermore, advanced training is required to use software platforms on which population PK/PD models run, presenting additional barriers to their clinical use.

We have developed an app to provide clinicians with a rapid, user-friendly way to assess prospectively the impact of dosage changes of olanzapine or risperidone or to estimate the dosage needed to reach a target concentration or D2 RO. To this end, the app offers two main functions. First, the ability to simulate PK profiles in treatment-naïve patients and offer dosing recommendations for targeting specific trough concentrations or D2 RO. Second, the adaptive dosing function, wherein the app can generate a PK profile based on one or two plasma concentration measurements, and can simulate new dosing regimens or, again, suggest a dosage that targets a specific trough concentration or D2 RO. Both functions incorporate prior information on population pharmacokinetic parameters and covariate effects to offer predictions based on limited data.

App performance was assessed both on speed and accuracy. In terms of speed, the app was able to complete model simulations in a matter of seconds, which may be important from the standpoint of ease of use and accessibility. In terms of accuracy, the predictions of the app had comparable bias and precision to that reported by Nakajima et al when using NONMEM [16]. This supports the predictive ability of the app. However, at this stage, its predictions should not yet be used to make clinical decisions. Until our results have been confirmed and extended, the app should be used only in research studies to quickly and conveniently investigate hypothetical, “what if” scenarios.

The ultimate, ongoing goal of this work is the development of a clinically useful tool for guiding the dosing of antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. In its current form, the app is limited to the scope of its underlying models in terms of what it can and cannot predict. The app can only offer predictions for two antipsychotics, olanzapine or risperidone. It is based on the relationships among dosages, concentrations, and D2 RO. While in turn, D2 RO has been linked to clinical outcomes (i.e., effectiveness and tolerability), the app does not offer direct predictions about clinical outcomes.

In summary, this study demonstrates that an app can provide rapid predictions and simulations using sparse data, with accuracy levels on par with complex population modeling software. This proof of concept supports the feasibility of implementing clinically individualized predictive dosing. Further testing and validation is needed to develop an app that could be used by clinicians. In particular, before an app can provide specific clinical recommendations, additional research is needed about the relationships between D2 RO and specific clinical outcomes. This work represents an important step towards the development of personalized, adaptive dosing of antipsychotics, a paradigm which could impact the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia.

What is already known about this subject.

Treatment with olanzapine or risperidone for schizophrenia requires close monitoring and careful titration to reach therapeutic concentrations

Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy is linked to clinical outcomes, and provides a targetable therapeutic window

Population PK models incorporating maximum a-posteriori Bayesian estimation can provide predictions of individual drug concentration and receptor occupancy

What this study adds.

A robust, rapid, and user-friendly software tool was developed for predicting olanzapine and risperidone drug concentrations and D2 receptor occupancy based on sparse sampling.

An easy-to-use user interface provides predictions that can be used to adjust olanzapine or risperidone dosages.

Funding Sources:

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Mental Health, grant R01AG031348, the National Institute on Aging, and the Peter and Shelagh Godsoe Chair in Late Life Mental Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Mulsant currently receives research support from Brain Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the CAMH Foundation, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the US National Institute of Health (NIH), Capital Solution Design LLC (software used in a study founded by CAMH Foundation), and HAPPYneuron (software used in a study founded by Brain Canada). Within the past three years, he has also received research support from Eli Lilly (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial) and Pfizer (medications for a NIH-funded clinical trial). He has been an unpaid consultant to Myriad Neuroscience.

Dr. Suzuki has received manuscript or speaker’s fees from Astellas, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Elsevier Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Yakuhin, Lundbeck, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, MSD, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, Shire, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tsumura, Wiley Japan, and Yoshitomi Yakuhin, and research grants from Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma and Shionogi.

Dr. Uchida has received grants from Eisai, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, and Meiji-Seika Pharma; speaker’s honoraria from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma, Eisai, and Meiji-Seika Pharma; and advisory panel payments from Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharma within the past three years.

No other authors reported potential conflicts of interest.

Hyperlinks used:

dopamine D2

Olanzapine

risperidone

9-OH risperidone

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, Welham J. Schizophrenia: A Concise Overview of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):67–76. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goff DC, Falkai P, Fleischhacker WW, et al. The Long-Term Effects of Antipsychotic Medication on Clinical Course in Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(9):840–849. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howes OD, Kapur S. The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: Version III--The Final Common Pathway. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):549–562. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwata Y, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Glutamatergic Neurometabolite Levels in Patients With Ultra-Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia: A Cross-Sectional 3T Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Study. Biol Psychiatry. 2019;85(7):596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwata Y, Nakajima S, Caravaggio F, et al. Threshold of Dopamine D2/3 Receptor Occupancy for Hyperprolactinemia in Older Patients With Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(12):e1557–e1563. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapur S, Zipursky R, Jones C, Remington G, Houle S. Relationship Between Dopamine D2 Occupancy, Clinical Response, and Side Effects: A Double-Blind PET Study of First-Episode Schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):514–520. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uchida H, Takeuchi H, Graff-Guerrero A, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, Mamo DC. Dopamine D2 Receptor Occupancy and Clinical Effects: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(4):497–502. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3182214aad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida H, Pollock BG, Bies RR, Mamo DC. Predicting Age-Specific Dosing of Antipsychotics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(4):360–362. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozawa C, Bies RR, Pillai N, Suzuki T, Mimura M, Uchida H. Model-Guided Antipsychotic Dose Reduction in Schizophrenia: A Pilot, Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(4):329–335. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000001046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchida H, Takeuchi H, Graff-Guerrero A, Suzuki T, Watanabe K, Mamo DC. Predicting Dopamine D2 Receptor Occupancy From Plasma Levels of Antipsychotic Drugs: A Systematic Review and Pooled Analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(3):318–325. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318218d339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai H, Yasui-Furukori N, Suzuki T, et al. Pharmacological Treatment of Schizophrenia: Japanese Expert Consensus. Pharmacopsychiatry. Published online 12 January 2021. doi: 10.1055/a-1324-3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeman P Atypical Antipsychotics: Mechanism of Action. FOCUS. 2004;2(1):48–58. doi: 10.1176/foc.2.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng Y, Pollock BG, Coley K, et al. Population pharmacokinetic analysis for risperidone using highly sparse sampling measurements from the CATIE study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(5):629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03276.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigos KL, Pollock BG, Coley KC, et al. Sex, Race, and Smoking Impact Olanzapine Exposure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(2):157–165. doi: 10.1177/0091270007310385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheiner LB, Stanski DR, Vozeh S, Miller RD, Ham J. Simultaneous modeling of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: Application to d-tubocurarine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1979;25(3):358–371. doi: 10.1002/cpt1979253358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima S, Uchida H, Bies RR, et al. Dopamine D 2/3 Receptor Occupancy Following Dose Reduction Is Predictable With Minimal Plasma Antipsychotic Concentrations: An Open-Label Clinical Trial. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(1):212–219. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong JF, Faccenda E, Harding SD, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2020: extending immunopharmacology content and introducing the IUPHAR/MMV Guide to MALARIA PHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D1006–D1021. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graff-Guerrero A, Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, et al. Evaluation of Antipsychotic Dose Reduction in Late-Life Schizophrenia: A Prospective Dopamine D2/3 Receptor Occupancy Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(9):927–934. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchida H, Graff-Guerrero A, Pollock BG, Rajji TK. Therapeutic Window for Striatal Dopamine D2/3 Receptor Occupancy in Older Patients with Schizophrenia: A Pilot PET Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. Published online 2014:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lammertsma AA, Hume SP. Simplified reference tissue model for PET receptor studies. NeuroImage. 1996;4(3 Pt 1):153–158. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron KT. Mrgsolve: Simulate from ODE-Based Models.; 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mrgsolve [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petzold L Automatic Selection of Methods for Solving Stiff and Nonstiff Systems of Ordinary Differential Equations. SIAM J Sci Stat Comput. 1983;4(1):136–148. doi: 10.1137/0904010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang W, Cheng J, Allaire JJ, Xie Y, McPherson J. Shiny: Web Application Framework for R.; 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=shiny [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexander SPH, Christopoulos A, Davenport AP, et al. THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176(S1):S21–S141. doi: 10.1111/bph.14748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.