Abstract

BACKGROUND

Paradoxical transtentorial herniation is a rare but life-threatening complication of cerebrospinal fluid drainage in patients with large decompressive craniectomy. However, paradoxical transtentorial herniation after rapid intravenous infusion of mannitol has not been reported yet.

CASE SUMMARY

A 48-year-old male suffered from a right temporal vascular malformation with hemorrhage. In a coma, the patient was given emergency vascular malformation resection, hematoma removal, and the right decompressive craniectomy. The patient woke up on the 1st d after the operation and was given 50 g of 20% mannitol intravenously every 8 h without cerebrospinal fluid drainage. On the morning of the 7th postoperative day, after 50 g of 20% mannitol infusion in the Fowler’s position, the neurological function of the patient continued to deteriorate, and the right pupils dilated to 4 mm and the left to 2 mm. Additionally, computed tomography revealed an increasing midline shift and transtentorial herniation. The patient was placed in a supine position and given 0.9% saline intravenously. A few hours later, the patient was fully awake with purposeful movements on his right side and normal communication.

CONCLUSION

Paradoxical herniation may occur, although rarely, after infusing high-dose mannitol intravenously in the Fowler’s position in the case of a large craniectomy defect. An attempt should be made to place the patient in the supine position because this simple maneuver may be life-saving. Do not use high-dose mannitol when the flap is severely sunken.

Keywords: Decompressive craniectomy, Intracranial hypotension, Paradoxical herniation, Transtentorial herniation, Mannitol, Case report

Core Tip: The paradoxical herniation is a rare but life-threatening complication in patients with large decompressive craniectomies. This case report suggests that mannitol treatment after a large decompressive craniectomy can cause a paradoxical herniation. Early recognition and proper treatment can save a patient's life.

INTRODUCTION

The paradoxical herniation is a rare but life-threatening complication of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage in patients with large decompressive craniectomies. This result is due to a combined effect of brain gravity, atmospheric pressure, and intracranial hypotension[1,2]. Paradoxical herniation has been reported after craniotomy in the context of CSF hypovolemia, usually ascribed to intraoperative or postoperative CSF drainage or spinal CSF fistula[1,3-5]. Currently, only a few cases have been reported that paradoxical herniation may occur in the absence of CSF drainage, which is somewhat different from our case[6-8]. We describe a unique case of spontaneous paradoxical herniation after intravenous infusion of mannitol and decompressive craniectomy.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 48-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with sudden weakness in his left limb.

History of present illness

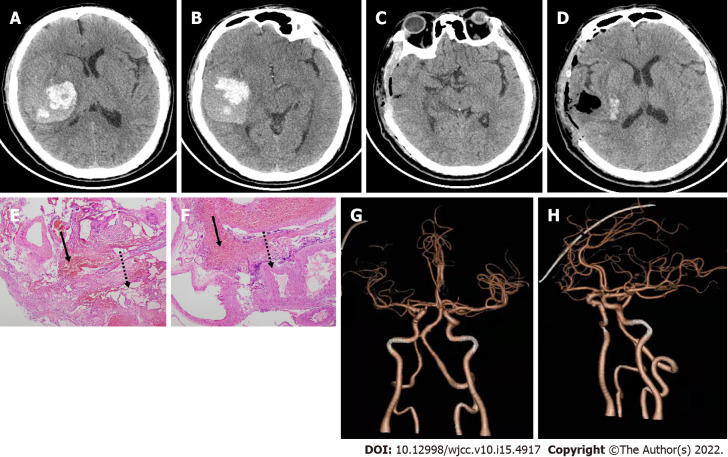

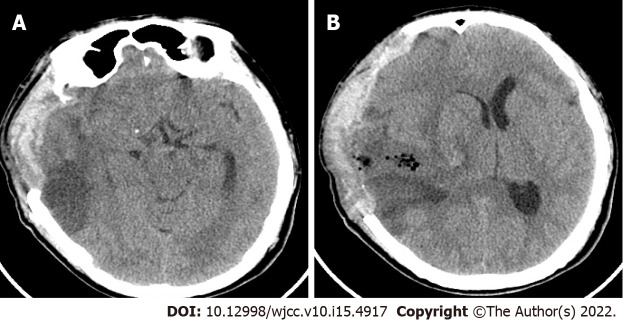

Two hours before his arrival, he suddenly developed weakness in his left limb and was unable to stand while working. The neurological examination showed a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8 and a left hemiparesis. An urgent head computed tomography (CT) examination revealed massive right temporal hemorrhage (Figure 1A and B). The patient underwent an emergent frontoparietal decompressive craniectomy with a duraplasty, and the hematoma was completely evacuated. A mass of abnormal blood vessels founded in the hematoma cavity during the operation was removed. Postoperative pathological examination revealed malformed blood vessels (Figure 1E and F). On the 1st d after the operation, the patient was fully awake with normal communication and directional movement of the right limb but had left hemiplegia. The head CT shows that the hematoma has been completely cleared, and the midline is almost in the middle (Figure 1C and D). The CT angiography shows normal cerebral vessels (Figure 1G and H). Although the flap pressure was not high, 50 g of 20% mannitol was given every 8 h to reduce local edema. On the morning of the 7th d after the operation, after an intravenous drip of 50 g of mannitol in the Fowler’s position, the neurological function of the patient continued to deteriorate, the right pupil dilated to 4 mm and the left to 2 mm. An urgent head CT revealed increasing midline shift, transtentorial herniation, and brainstem compression (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Axial computed tomography scans, postoperative computed tomography angiography and histopathology. A and B: Tight temporal hemorrhage on the day of admission; C and D: Hematoma is completely cleared on the 1st d after the operation; E and F: Histopathology (E and F, hematoxylin and eosin stain), original × 40 magnification. Dashed arrows indicate vascular malformations with an uneven thickness of the blood vessel wall and varying size of the blood vessel cavity. Solid arrows indicate many red cells in the blood; G and H: Computed tomography angiography showing normal cerebrovascular after the operation.

Figure 2.

Axial computed tomography images. A and B: Transtentorial herniation on the 7th d after the operation.

History of past illness

The patient had no history of systemic diseases.

Physical examination

Neurologic examination revealed a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 8, with no eyes open. The pupils dilated to 4 mm on the right and 2 mm on the left, with left hemiplegia.

Laboratory examinations

On the 7th d after the operation, the patient underwent a blood cell analysis and examinations of blood electrolyte, liver function, and renal function. The test results were all normal, except for a slight decrease in the blood sodium concentration (130.3 mmol/L) and chlorine concentration (94.3 mmol/L). On the 8th d after the operation, examination of blood electrolyte showed sodium concentration (132 mmol/L) and chlorine concentration (95.6 mmol/L).

Imaging examinations

An urgent head CT revealed increasing midline shift, transtentorial herniation, and brainstem compression (Figure 2).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with paradoxical herniation.

TREATMENT

Aggressive medical treatment was immediately initiated to lower intracranial pressure (ICP), including 30° Fowler’s position and 20 mg intravenous bolus of furosemide. However, neurological symptoms continued to worsen, and the patient went into lethargy. During the active preparation for the operation, a significant phenomenon was found: regular brain beats could be seen under his obviously sinking flap. Therefore, we considered that the brain herniation was caused by the brain sag due to low ICP, and therefore, instead of operating, the patient was therefore placed in a supine position and quickly replenished with 9% saline intravenously.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

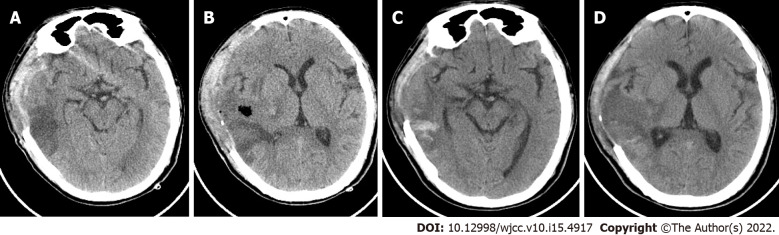

A few hours later, with the sinking skin flap relieving, the neurological function of the patient was significantly improved, and consciousness returned. However, the left side remained hemiplegia, and the right pupil dilated to 4 mm. The next day, the head CT showed resolution of transtentorial herniation, a significant decrease in midline shift, and reappearance of basal cisterns (Figure 3A and B). The neurological function of the patient continued to improve, and the patient was successfully changed from a supine position to the Fowler’s position within a few days. Two weeks later, he was able to stand and walk with the help of others. The right pupil contracted to 3 mm and the left pupil 2 mm, with a restored light reflection. The head CT shows that hematoma and edema have been absorbed entirely (Figure 3C and D). He was eventually transferred to a rehabilitation facility, waiting for the next skull repair surgery. The 2-mo follow-up revealed a good prognosis with mild hemiplegia on the left side (muscle strength grade 4).

Figure 3.

Axial computed tomography images. A and B: Resolution of transtentorial herniation the day after transtentorial herniation; C and D: Hematoma and edema are completely absorbed 2 wk after the operation.

DISCUSSION

Paradoxical herniation, a rare complication of patients who have undergone craniotomy, refers to transtentorial herniation in the context of intracranial hypotension[3,6]. This life-threatening complication has been reported after various types of CSF depletion and drainage, including CSF leakage, lumbar puncture, lumbar drain, CSF shunt, and ventriculostomy in patients undergoing a decompressive craniectomy[4,9-11]. The pathological mechanism of this rarely reported complication is unclear and may be related to atmospheric pressure, cerebral gravity, positional changes, and CSF exhaustion[3,6,7]. Interestingly, there are many reports of sinking skin flap syndromes after large craniectomy, with a series of symptoms, including motor dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, headache, mood disorders, and sensory disturbance, most of which can be improved by cranioplasty[12,13]. The syndromes have a similar pathological mechanism with paradoxical herniation; however, the difference is that the symptoms are mild, slow to deteriorate, not life-threatening, and usually occur several months after decompressive craniectomy[14,5].

So far, there are only a few cases of paradoxical herniation without CSF drainage. If a patient begins rebleeding after intracranial hematoma removal, reoperation should be performed to remove the hematoma and cranioplasty; if paradoxical herniation occurs after surgery, the possibility of CSF loss during multiple operations should be considered[8]. Another report of paradoxical herniation that occurred 1 h after removing acute subdural hematoma was suspected to be due to the loss of a large amount of CSF during the operation; the patient improved after an immediate cranioplasty[6]. Interestingly, a patient with massive cerebral infarction caused by middle cerebral artery embolization developed paradoxical herniation 8 d after decompressive craniectomy, and the neurological function in the upright position continued to deteriorate. These symptoms were resolved by placing the patient in the Trendelenburg position and hydrating the patient quickly, considering the location changes of the patient[7].

Our case is unique in that paradoxical herniation occurred after a rapid intravenous drip of 50 g of 20% mannitol in the Fowler’s position, without CSF drainage. Importantly, we found that the skin flap significantly sank after mannitol. In this case, the paradoxical herniation caused by brain sag. This may be due to the loss of the close attachment of the dura mater to the skull, the brain to sag from its own gravity and the differences in the intracranial and extracranial pressure. Additionally, patients with low flap pressure cannot handle large doses of mannitol, as this can lead to life-threatening paradoxical herniation. In this case, the patient's life was quickly saved by changing their position, which avoided reoperation in the short term. Interestingly, several hours after the treatment, including supine position, intravenous rehydration, and stopping mannitol, the depressed flaps gradually protruded with the improvement of the nerve function, indicating ICP had increased.

Treatment of paradoxical herniation should include immediately placing the patient in the supine or Trendelenburg position, providing intravenous fluids, and discontinuing all medications designed to reduce ICP[7,8]. In addition, by clamping all CSF drainage tubes or performing CSF leakage repair to solve the underlying cause of CSF loss, clinical improvement is usually expected within a few hours[4]. Emergency cranioplasty is also a treatment option[6].

CONCLUSION

After large bone craniectomy and decompression, long-term treatment with large amounts of mannitol may cause a rare paradoxical herniation. Paradoxical herniation should be considered if flaps are severely sunken, the brain beating under the skin flap is normal, and head CT excludes secondary intracranial hypertension. Placing the patient in the supine or Trendelenburg position, along with rehydration therapy, may quickly save lives without the need for another operation.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: September 19, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Article in press: April 3, 2022

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chrastina J, Czech Republic; Moshref RH, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Chuan Du, Neurosurgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University, Chengdu 610000, Sichuan Province, China.

Hua-Juan Tang, Neurology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610000, Sichuan Province, China.

Shuang-Ming Fan, Neurosurgery, the Affiliated Hospital of Chengdu University, Chengdu 610000, Sichuan Province, China. 297551802@qq.com.

References

- 1.Cholet C, André A, Law-Ye B. Sinking skin flap syndrome following decompressive craniectomy. Br J Neurosurg. 2018;32:73–74. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2017.1390065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebastianelli L, Stoll V, Versace V, Martignago S, Obletter S, Lavoriero M, Malfertheiner K, Gisser G, Saltuari L. Short-Term Memory Impairment and Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Dysfunction in the Orthostatic Position: A Single Case Study of Sinking Skin Flap Syndrome. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2015;2015:318917. doi: 10.1155/2015/318917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creutzfeldt CJ, Vilela MD, Longstreth WT Jr. Paradoxical herniation after decompressive craniectomy provoked by lumbar puncture or ventriculoperitoneal shunting. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:1170–1175. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS141810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gschwind M, Michel P, Siclari F. Life-threatening sinking skin flap syndrome due to CSF leak after lumbar puncture - treated with epidural blood patch. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19:e49. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2012.03672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schievink WI, Palestrant D, Maya MM, Rappard G. Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leak as a cause of coma after craniotomy for clipping of an unruptured intracranial aneurysm. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:521–524. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiruta R, Jinguji S, Sato T, Murakami Y, Bakhit M, Kuromi Y, Oda K, Fujii M, Sakuma J, Saito K. Acute paradoxical brain herniation after decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury: A case report. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:79. doi: 10.25259/SNI-235-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michael AP, Espinosa J. Paradoxical Herniation following Decompressive Craniectomy in the Subacute Setting. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2016;2016:2090384. doi: 10.1155/2016/2090384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahme R, Bojanowski MW. Overt cerebrospinal fluid drainage is not a sine qua non for paradoxical herniation after decompressive craniectomy: case report. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:214–215; discussion 215. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000370015.94386.1F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender PD, Brown AEC. Head of the Bed Down: Paradoxical Management for Paradoxical Herniation. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:208–210. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2019.4.41331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chughtai KA, Nemer OP, Kessler AT, Bhatt AA. Post-operative complications of craniotomy and craniectomy. Emerg Radiol. 2019;26:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1647-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen L, Qiu S, Su Z, Ma X, Yan R. Lumbar puncture as possible cause of sudden paradoxical herniation in patient with previous decompressive craniectomy: report of two cases. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:147. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-0931-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ji H, Chen W, Yang X, Guo J, Wu J, Huang M, Cai C, Yang Y. Paradoxical Herniation after Unilateral Decompressive Craniectomy: A Retrospective Analysis of Clinical Characteristics and Effectiveness of Therapeutic Measures. Turk Neurosurg. 2017;27:192–200. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.15643-15.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woo PYM, Mak CHK, Mak HKF, Tsang ACO. Neurocognitive recovery and global cerebral perfusion improvement after cranioplasty in chronic sinking skin flap syndrome of 18 years: Case report using arterial spin labelling magnetic resonance perfusion imaging. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Annan M, De Toffol B, Hommet C, Mondon K. Sinking skin flap syndrome (or Syndrome of the trephined): A review. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:314–318. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1012047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Rienzo A, Colasanti R, Gladi M, Pompucci A, Della Costanza M, Paracino R, Esposito D, Iacoangeli M. Sinking flap syndrome revisited: the who, when and why. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43:323–335. doi: 10.1007/s10143-019-01148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]