Abstract

Building the next generation of telehealth enabled professionals requires a mixture of team-based, interprofessional practice with novel technologies that connect providers and patients. Effective telehealth education is critical for the development of multidisciplinary training curricula to ensure workforce preparedness. In this study, we evaluated the impact of a formal telehealth education curriculum for interprofessional students through an online elective. Over 12 semesters, 170 students self-selected to enroll in the 3-credit hour interprofessional elective and took part in structured didactic, experiential and interprofessional learning opportunities. Mixed-method assessments show significant knowledge and confidence gains with students reflecting on their roles as future healthcare providers. The results from five years’ worth of course data shows not only an opportunity to advance the individual knowledge of trainees, but a larger movement to facilitate changes in practice towards population health goals. Recent global health events have further highlighted the need for a rapid response to public health emergencies by highly trained provider teams who are able to utilize technology as the cornerstone for the continuity of care.

Keywords: Telehealth, curriculum, interprofessional, training, health professions, academic medical

Introduction:

Telehealth, the provision of clinical, research and health education services through technology, has shifted from a future state concept to an integral part of the healthcare delivery landscape (Smith et al., 2020). In addition to supporting care through the connectivity of providers and patients, telehealth enables the advancement of interprofessional practice as a corner stone for future healthcare delivery. By weaving the concepts of team-based care with the opportunities afforded by technological innovation, training programs are able to cross long established lines in order to support the needs of an interoperable healthcare system (Rutledge, Hawkins, Bordelon, & Gustin, 2020). There are established roles, opportunities and risks that have to be factored in to an academic medicine telehealth program (King & Shipman, 2019). A key to improving telehealth quality, efficiency, and adoption across training programs is integrating effective telehealth education into established multidisciplinary training curricula, so that team members enter the workforce prepared to lead telehealth initiatives.

Building the next generation of telehealth enabled professionals requires a mixture of team-based, interprofessional practice with technologies that are interoperable. There is clear recognition that health professions training programs provide an important means to prepare future providers and leaders to adapt in a changing telehealth landscape (Papanagnou, Sicks, & Hollander, 2015; Pourmand et al., 2020). Still, fully integrated curricula are rare within the literature as are robust research studies tracing the training efficacy (Chike-Harris, Durham, Logan, Smith, & DuBose-Morris, 2020; Kirkland, DuBose-Morris, & Duckett, 2019). Little in the way of formal research has been conducted showing the process for the development of telehealth curriculum or giving guidelines for implementation (Chike-Harris, Durham, et al., 2020). While it is established that telehealth education should be included in formal training programs, significant gaps exist within the literature regarding the consistency in which health professions training programs incorporate formal telehealth curriculum (Chike-Harris, Harmon, & Van Ravenstein, 2020; Rutledge et al., 2020).

In this study, we administered pre- and post-course surveys to interprofessional students to evaluate the impact of a formal telehealth education curriculum on self-perception of students’ expertise in, comfort with, and potential for integrating telehealth into interprofessional practice. With multi-professional participation from six different Colleges at the Medical University of South Carolina, this evaluation provides an assessment of the impact of telehealth education on a broad and diverse group of students.

Background:

Course Description

In the summer of 2014, a group of faculty experts at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) were offered the opportunity to extend out their knowledge of telehealth best practices through an interprofessional elective that would become a part of the reoccurring course offerings. Based off of Kern’s established six-step curriculum development model for medical education (Thomas, Kern, Hughes, & Chen, 2015), an interprofessional education elective was piloted in person to address the growth of telehealth as a modality of healthcare delivery and the need to integrate curriculum into formal programs for healthcare professionals. The faculty team applied Kern’s model to: identify the education problem (need to train rising generation of providers and healthcare team members); conduct a targeted needs assessment (who was being taught and in what environment); establish the goals and objectives of the course (increase knowledge and comfort levels with telehealth modalities); design the educational strategies (hybrid course focusing on telehealth champion experiences and evolving best-practices in clinical care); implementing the curriculum (through an iterative approach); and finally, evaluating the learners and course in order to achieve and maintain efficacy.

The curriculum sets the stage for student engagement by explaining how the evolution of telehealth factors into changing models of care; the progression of technical, legal and regulatory guidelines; and utilizes a team-based approach that is supported by health informatics technologies. Video interviews with content experts are offered as examples of how service development occurs and prompts students to focus on resource identification, knowledge acquisition and continual learning for career preparation. Students are provided with a tour of the on-campus Telehealth Learning Commons which is a living laboratory for training and technology integration. To demonstrate the application of knowledge and skills gained, students work as interprofessional teams to develop case presentations that address a specific clinical diagnosis process from treatment planning through care coordination. End of module assignments required students to post responses to an online discussion forum, ask the faculty directors and/or their fellow students pertinent questions and review the collective submissions.

In order to expand the course so that it was fully available for students across the six colleges (see Tables 1 and 2), the course was translated into an online, asynchronous learning experience (Moodle™) modeled after the delivery of telehealth services (Weinstein et al., 2010). Over 12 semesters, 170 students self-selected to enroll in the 3-credit hour interprofessional elective and took part in structured didactic, experiential and interprofessional learning opportunities as their academic program schedules allowed. Programs of study included disciplines in medicine, nursing, pharmacy, dentistry, therapeutics, administration, and clinical research. Due to variances among the grading systems across the six colleges, the course is graded as pass/fail to standardize grading.

Table 1.

Program Participants by Academic Year and College

| College | Program Name | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College of Dental Medicine | Doctor of Dental Medicine | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| College of Graduate Studies | MS in Clinical Research | 1 | 1 | ||||

| PhD in Biostatistics | 1 | 1 | |||||

| GP.BMTRY: PhD in Biometry & Epidemiology | 1 | 1 | |||||

| College of Health Professions | MS in Health Informatics | 10 | 4 | 3 | 17 | ||

| Master of Health Administration - Executive | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | |

| Master of Health Administration - Residential | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 11 | |

| MS in Physician Assistant Studies | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| MS in Occupational Therapy | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Doctor of Health Administration | 5 | 2 | 6 | 13 | |||

| Doctor of Physical Therapy | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| College of Medicine | Doctor of Medicine | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 22 |

| Master of Public Health - Epidemiology | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Master of Public Health - Health Behavior & Health Promotion | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Master of Public Health - Biostatistics | 1 | 1 | |||||

| College of Nursing | MS in Nursing - Family Nurse Practitioner: PostB | 1 | 1 | ||||

| DNP - Advanced Practice Nurse: PostM | 1 | 1 | |||||

| DNP - Family Nurse Practitioner: PostB | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| DNP - Psychiatric Mental Health: PostB | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Accelerated BS in Nursing | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| RN to BSN | 1 | 1 | |||||

| College of Pharmacy | Doctor of Pharmacy | 8 | 9 | 13 | 15 | 45 |

Table 2.

Number of Respondents by Year, Semester and Pre/Post Survey Status

| Year and Semester | Pre | Post |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 2015 | ||

| Fall | 13 | 9 |

|

| ||

| 2016 | ||

| Spring | 12 | 6 |

| Summer | 3 | 2 |

| Fall | 10 | 10 |

|

| ||

| 2017 | ||

| Spring | 16 | 14 |

| Summer | 19 | 15 |

| Fall | 14 | 10 |

|

| ||

| 2018 | ||

| Spring | 12 | 13 |

| Summer | 20 | 18 |

| Fall | 5 | 3 |

|

| ||

| 2019 | ||

| Spring | 21 | 18 |

| Summer | 18 | 14 |

|

| ||

| Total | 163 | 132 |

Materials and Methods:

Survey Instruments

A conceptual framework for the evaluation of the curriculum allowed for an examination of this multi-faceted learning experience based on Kirkpatricks’ revised model (Kirkpatrick & Kirpatrick, 2016). To obtain a baseline of students’ self-perceived knowledge and comfort level with telehealth as outlined in Kirkpatrick’s model (reaction and learning), data was collected through a REDCap Survey prior to starting coursework (Harris et al., 2009). The survey items were developed by the team of interprofessional course instructors to assess student self-perceived knowledge and comfort with telehealth, with 5-point Likert scale response choices. Students self-evaluated their participation in the final group project based off teamwork effectiveness. Upon the conclusion of the semester, students also self-completed a post-course evaluation to again gauge their self-perceived knowledge and comfort level with telehealth concepts and application. To achieve the higher levels of Kirkpatrick’s model for evaluation (behavior and results), students were encouraged to adjust their behaviors within their training programs as well as their clinical or administrative practice to apply the content to experiential opportunities. Post-course survey analysis gauged their achievement of the desired learning outcomes through open-ended responses. These open-ended responses were then subjected to thematic qualitative analysis.

Per Table 3, course topics, learning methods in the evaluation of student deliverables is outlined. A 3- to 4-person faculty team serves as facilitators for the course, helping to direct activities and answer required student poised questions at the end of each module. Utilizing Creswell et al. (2003), we chose a concurrent transformative mixed method design, meaning that we concurrently collected quantitative and qualitative data and that the priority of those are equal. The quantitative and qualitative data are integrated during the interpretation phase. This mixed-method study design was essential to the ongoing development of the curriculum as it highlighted areas where the curriculum needed to be refined or expanded based on the individual and interprofessional perspectives provided each semester. The study was considered a quality improvement project and was determined exempt from IRB review by the academic medical center.

Table 3.

Course Topics, Learning Methods Student Deliverables

| Topic | Learning Methods | Student Deliverables | Learning Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Course Introduction | Pre-Survey, Student Self-Introduction | RedCap Survey | Baseline Knowledge Assessment |

| Module 1: History & Changing Models of Care | Recorded Subject-Matter Expert Interviews, Academic Publications & Digital Content | Discussion Forum Post | Faculty Scoring of Post & Feedback |

| Module 2: Access & Population Health | Discussion Forum Post | Faculty Scoring of Post & Feedback | |

| Module 3: Technology: Infrastructure and Applications | Discussion Forum Post & Mobile App Review | Faculty Scoring of Post, Scoring of Mobile App Review & Feedback | |

| Module 4: Legislation & Regulation | Discussion Forum Post & Telehealth Experience Reflection | Faculty Scoring of Post & Feedback | |

| Module 5: Team-Based Care & Community Partnerships | Discussion Forum Post | Faculty Scoring of Post & Feedback | |

| Final Project & Course Conclusion | Group Presentation Based on Interprofessional Case | Group Presentation, Discussion Forum Post, and RedCap Survey | Student-Team Evaluation, & Discussion Forum Posting & Post-Survey |

Data Analysis

The data were unable to be matched on an individual level between pre- and post-assessment due to the anonymous nature of responses. Pre and post self-assessment of knowledge results of survey questions were explored using chi-squared and Fishers exact tests as appropriate. We tested for differences between cohorts across the variables using Fishers exact test. The answers to the open-ended questions were analyzed using conventional content analysis. This qualitative research method aims to interpret the content of text through coding, systematic classification, and theme identification (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Through an inductive approach, two researchers independently developed a code set for each open-ended question. These codes were then grouped into themes and reviewed as a team. Any discrepancies in codes and their definitions were discussed and reconciled until a final coding scheme and a hierarchy was established. This final coding scheme was then applied by a single researcher to the text (Supplement 1).

Results:

No significant differences were found between cohorts across time in any questions of pre- or post-assessments using Fishers exact test (data not shown). Therefore, all pre-responses were combined, as well as optional post-course survey responses. While the growth of telehealth and direct to consumer technologies over time would seem to lead to incoming students having a higher level of self-professed knowledge, competency and comfort related to telehealth and interprofessional practice, the data show that not to be the case. Over the multiple course offerings, students do not enter with a greater knowledge of the evolution of telehealth as the change in pre-test baseline scores is not statistically significant (p=0.952).

Students do reflect clear growth in knowledge and confidence over the course of the semester (Figure 1). In the pre-assessment scores (n=163), only 6.1% of students felt comfortable explaining three different telehealth tools while post course 78% could. Post-test scores (n=132) show high levels of perceived utilization in future clinical, educational or research practice (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of “Above Average” Responses to Items by Pre- and Post-Curriculum Administration (all values are p<0.001 using Fisher’s exact tests)

Figure 2.

I would rate my ability to utilize telehealth as part of my current or future clinical, educational or research practice as… (p<0.001 using a Fisher’s exact test)

Open-Ended Survey Questions – Qualitative Thematic Counts

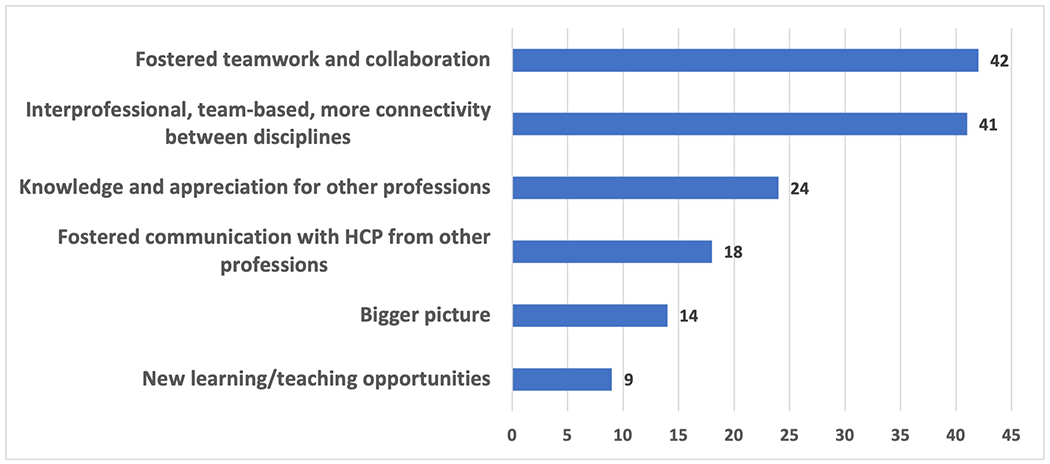

In addition to analyzing quantitative student survey data, we also conducted qualitative thematic counts on the open-ended student responses. These counts revealed themes related to the students’ self-perceived roles as healthcare providers (Figure 3) highlighting an increase in teamwork and collaboration due to interprofessional connectivity. The knowledge gained from working with other disciplines and understanding the potential for improved communication across professions were key influencers students perceived in their roles as health care professionals. Student quotes illustrate each of the primary themes (Table 4). In addition, students clearly interpreted their roles as leveraging telehealth to increase the quality of care for their patients, and therefore, positively affecting the patients experience and outcomes (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Course Influenced Role Among Health Care Professionals

Table 4.

Qualitative Themes and Quotes

| Project Completion Practices Learned That I Will Use in the Future | ||

| “Through interprofessional collaboration, patient-centered care can truly occur. With telehealth connecting both patients and a team of health care providers, patients become the center of their own “ring of care” with the providers encircling him or her….With telehealth, patient-centered care, including education, can realistically be practiced continuously in real-time, all the time.” | “Aspects of each teamwork competencies of knowledge, skills, and attitudes identified in the MUSC Team Competencies were used within my team throughout our final project. All team members acknowledged understanding effective teamwork including use of group dynamic processes of communication, decision making, group problem solving, and group development strategies….Overall, the group implemented many teamwork competencies to produce a well-informed final project.” | |

| Course Influenced Role as a Professional in a Career Field | ||

| “The nature of telehealth creates an environment of communicability. It eliminates barriers such as distance and time management. Referrals, consultations, and team-based care are all facilitated by telehealth. As such, it will greatly benefit patients and their care as well as providers whose goal should be to improve quality of and access to care.” | “This course has taught me that it is not different professions of healthcare pitted against each other. I am not a one-man team and it is okay to seek advice/collaboration between other professionals for the greater good. I think that I perceived that in the future, I would- for a lack of a better phrase, be carrying the weight of the world on my shoulders. That is not the case, there are a lot of us out there with big dreams and goals that are more than willing to help. Diverse backgrounds and educations just make your team more well-rounded.” | |

| Telehealth Impact on Collaboration with Regard to Healthcare in General | ||

| “This course has influenced my perceived role as a healthcare professional and the role of other professionals in a very positive way. It has helped to instill in me an excitement for utilizing telehealth to advance healthcare solutions in the future. The course has supported my belief that it takes ALL members of a team to provide the best outcomes for our patients and I am thrilled to be entering a field where telehealth and telerehab are fostering healthcare delivery improvements within a collaborative space.” | “If anything, this course has made me feel more empowered, I now feel like I can bring an innovative prospective to any work site that others may not readily consider. This exposure to telehealth and telemedicine can help me to improve access and quality of care to patient populations who are in need. I could also use what I have learned here to aid in creating cost-effective solutions for health care institutions I may work for. This course has also inspired me to do more research into telepharmacy.” | |

| Telehealth Impact for Patients | ||

| “Not being a healthcare professional yet, I can only comment on how this course has influenced my view of healthcare in general. Since the start of this course I’ve looked at every medical encounter myself or my family has had with a new perspective. At every encounter I find myself thinking: How could telehealth be utilized for this service?; How much more convenient would this be for me as a patient?; and How much time/money/frustration would a telehealth solution have saved me in this situation? Particularly in the age of Patient and Family Centered Care having more healthcare professionals think in this way would be hugely beneficial for all involved in the healthcare industry.” | “I still perceive my role to be vital in my future patients’ medical care. I now believe that I am responsible for integrating the input from many different healthcare professionals so that my patients are getting the best care possible.” | |

| Telehealth Impact for Healthcare System | ||

| This course has taught me that telehealth is a group sport and with a little innovation (and technology), we can bring high quality healthcare to those that need it the most. I also believe telehealth can help to expand relationships as we see them today and make people think differently as we attempt to enhance the way we approach health delivery in the future. | The advantages of telehealth will extend my ability to collaborate and coordinate with other professionals by allowing me and my patients easier access to them. By making telemedicine as ubiquitous and boring as light bulbs, patients and providers will become more connected than ever before. | This course convinced me of the power and viability of telehealth services. As a future healthcare administrator, I want to ensure the organizations I work for are cognizant of this emerging technology and use it to improve their patients’ quality of care. As these services become reimbursed more consistently, I believe it will be crucial for organizations to account for telehealth in their strategic and business planning. |

Figure 4.

Course Influenced Role with Regard to Direct Patient Care

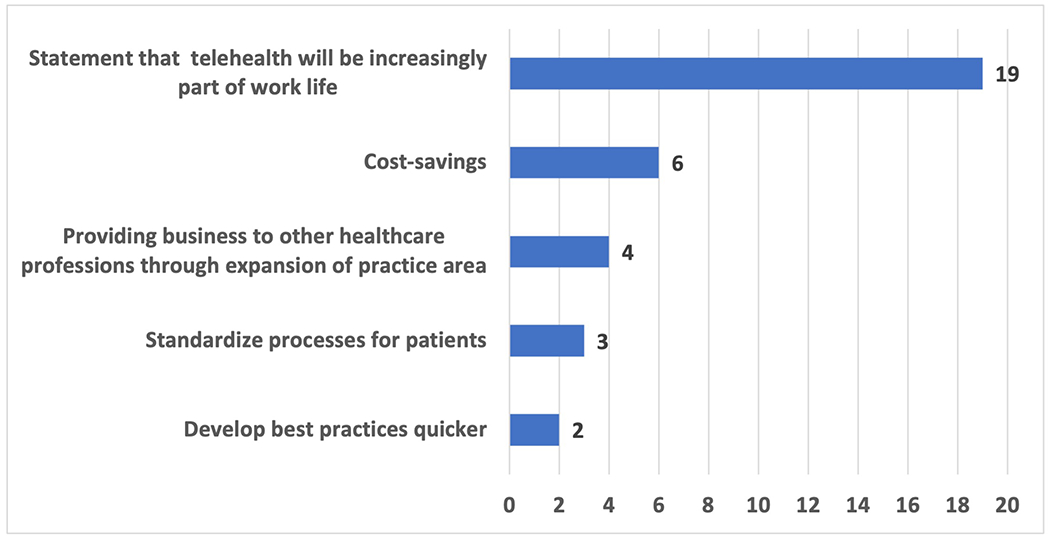

Given the mix of student tenure within their training programs, students’ perceptions of what their impact could be as providers or administrators in the healthcare system varied, but a common recognition was the universal possibility of what telehealth affords providers now and, in the future (Figure 5). This expanded their career perceptions and left them better prepared to care for patients (Figure 6). Some even described telehealth as a way to “get back” to the patient. Overall, students identified telehealth as a method to provide better quality of care for patients through several factors (Figure 7) and that telehealth would be a part of their careers moving forward (Figure 8).

Figure 5.

Course Influenced Role in the Healthcare System

Figure 6.

Course Influenced Role as a Professional in a Career Field

Figure 7.

Telehealth Impact for Patients

Figure 8.

Telehealth Impact for Healthcare System

Discussion:

The results from five years’ worth of course data shows not only an opportunity to advance the individual knowledge of trainees, but a larger movement to facilitate changes in practice towards population health goals. Students enter the course expecting to learn about technology, but instead learn more about what type of provider they expect to be and how best to structure their remaining training for a telehealth infused future practice. In addition to self-exploration, students better understand the C3 collaborative principals. This includes increased knowledge of other professions as well as how the students can partner across disciplines to create practice structures that support patients across health care delivery and translational research contexts (Blue, 2010). Empowered with foundational telehealth concepts, students are encouraged to be active drivers of the implementation of informatics within their practice settings in order to reduce burnout and professional isolation (Arora et al., 2007).

The focus of this training is made possible by the frameworks established by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and other accrediting bodies (Hübner et al., 2019; Krupinski & Weinstein, 2013) and by the structures afforded academic health systems that serve as the hub of specialty services. As telehealth has developed, so too have the competencies and need to translate established guidelines for physical examinations into virtual consultations (Ansary, Martinez, & Scott, 2019). More recently, higher order training to prepare providers to engage in telehealth etiquette, or “webside manner,” has addressed the need for mindful implementation of complex interpersonal communications that ensure quality care (Gustin, Kott, & Rutledge, 2020).

As public health and telehealth intersect in the pandemic response, it is increasingly important to build systems that can be implemented quickly and effectively (Agate, 2017). Telehealth education is also a way to develop education for patients and community members. An example is seen with the pharmacy and nursing students who complete this didactic course and then transition into teleprecepted experiences within local health centers where they work directly with patients under limited supervision (Fowler, Durham, Sterrett, Smith, & VanRavenstein, 2019). Initial findings show this training continuum allows for students to move into practice quicker with less need for onsite training within an interprofessional setting.

Similar success has been seen in telehealth educational interventions for residents based on this foundational course structure (Kirkland et al., 2019). Curriculum based on this IP model is tailored to meet residents at their levels of practice with 1st-years getting high-level overviews, 2nd-years engaging in an online didactic course and 3rd-years shadowing and demonstrating proficiency with telehealth services. Residents plan to pay it forward and “use [the course] to train fellow physicians and support staff”.

Furthermore, continuing education models have been developed for practicing providers who need certification for privileging and credentialing (DuBose-Morris, Cochran, & Epps, 2013). Providers are required to demonstrate proficiency in basic telehealth concepts as well as in equipment and processes specific to their disciplines and program areas. The faculty members responsible for the ongoing development of these initiatives view telehealth education as a continuing education imperative for future practice.

There are several limitations to this study. First historical survey system restraints prevented the tracking of individual student survey data. Therefore, we were able to assess impact on self-perceived knowledge only at the aggregate level. Since completion of the survey was voluntary, totals for those students who completed the initial pre-evaluation and those who voluntarily complete the post-evaluation are not equal. Finally, these survey instruments were designed for quality improvement purposes and customized to meet the course needs but not based on a previously validated instrument. Since, the survey has been validated as part of graduate medical education curriculum offerings across multiple institutions.

Conclusions:

As this study shows, the baseline of perceived knowledge in telehealth has not significantly changed over time for learners. The formal development of competencies to guide the current and future provision of education and certification should be of upmost importance for training programs and their accrediting bodies. As evidenced by this course, significant improvements of confidence and knowledge metrics are attainable over the course of a single semester. These interventions have been supported through an interprofessional context as a way to support the next generation of healthcare providers and administrators. Recent global events have further highlighted the need for a rapid response to public health emergencies utilizing technology as the cornerstone for continuity of care.

Continuing education to support learners as they acquire skills and competency with the processes being provided for their use in clinical and research settings is of paramount importance. Additional data are needed to determine optimal training program configurations that account for multiple disciplines and for the realities of a changing healthcare climate. Telehealth education is fundamental to that solution.

Supplementary Material

Supplement 1: Open-Ended Comments Coding Hierarchy

IP 717: Telehealth Teams of the Future Syllabus (updated link for publication will be provided)

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to a collaborative group of educators, evaluators, and content experts for helping to advance telehealth education as part of health professions training programs. The development of the course was encouraged by Dr. Mary Mauldin who identified early the need for telehealth education within an interprofessional context. A special thanks goes to all the students who help to make this course a part of their future practice and inform the development of additional resources for interprofessional teams. Finally, a sincere thanks goes out to every student now serving as a provider utilizing telehealth to better serve their patients.

Funding:

The development of this manuscript was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of the National Telehealth Center of Excellence Award (U66 RH31458-01-00). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. This publication was also supported in part by NIH/NCATS SPROUT-CTSA Collaborative Telehealth Network Grant Number U01TR002626. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement:

The authors have no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Contributor Information

Ragan DuBose-Morris, Academic Affairs Faculty, Center for Telehealth, Medical University of South Carolina, 169 Ashley Avenue, Suite 268, MSC 332, Charleston, SC 29425.

S. David McSwain, Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Medical University of South Carolina, 261 Calhoun St, Suite 305, MSC 186, Charleston, SC 29425.

James T. McElligott, Medical University of South Carolina, 169 Ashley Avenue, Suite 268, MSC 332, Charleston, SC 29425.

Kathryn L. King, Center for Telehealth, Medical University of South Carolina, 169 Ashley Avenue, Suite 268, MSC 332, Charleston, SC 29425.

Sonja Ziniel, Pediatrics-Pediatric Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, 13123 East 16th Ave, Box 302, Aurora, CO 80045.

Jillian Harvey, Doctor of Health Administration Division, Department of Healthcare Leadership and Management, Medical University of South Carolina, 151B Rutledge Ave, MSC 962, Charleston, SC 29425.

References:

- Agate S (2017). Unlocking the Power of Telehealth: Increasing access and services in underserved, urban areas telehealth background. Harvard Journal of Hispanic Policy, 29, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ansary AM, Martinez JN, & Scott JD (2019). The virtual physical exam in the 21st century. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1357633X19878330. 10.1177/1357633X19878330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora S, Geppert C. M. a, Kalishman S, Dion D, Pullara F, Bjeletich B, … Scaletti JV (2007). Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Academic Medicine, 82(2), 154–160. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue AV (2010). Creating collaborative care (C3), Medical University of South Carolina. Journal of Allied Health, 39(SUPPL. 1), 2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chike-Harris KE, Durham C, Logan A, Smith G, & DuBose-Morris R (2020). Integration of Telehealth Education into the Health Care Provider Curriculum: A Review. Telemedicine and E-Health, tmj.2019.0261. 10.1089/tmj.2019.0261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chike-Harris KE, Harmon E, & Van Ravenstein K (2020). Graduate nursing telehealth education: Assessment of a one-day immersion approach. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41(5), E35–E36. 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Clark VP, Gutmann ML, & Hanson WE (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Tashakkori A & Teddlie C (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research (pp. 209–240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- DuBose-Morris R, Cochran K, & Epps CC (2013). Applying Statewide Innovation Through Infrastructure and Partnership. Journal of the National AHEC Organization, XXIX(1), 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler T, Durham C, Sterrett J, Smith W, & VanRavenstein K (2019). A Nurse Practitioner Led Interprofessional Chronic Disease Management Model Utilizing Pharmacy Telehealth. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/18850 [Google Scholar]

- Gustin TS, Kott K, & Rutledge C (2020). Telehealth Etiquette Training: A Guideline for Preparing Interprofessional Teams for Successful Encounters. Nurse Educator, 45(2), 88–92. 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hübner U, Thye J, Shaw T, Elias B, Egbert N, Saranto K, … Ball MJ (2019). Towards the TIGER International Framework for Recommendations of Core Competencies in Health Informatics 2.0: Extending the Scope and the Roles. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 264, 1218–1222. 10.3233/SHTI190420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SL, & Shipman SA (2019). Telehealth in Academic Medicine: Roles, Opportunities, and Risks. Academic Medicine, 94(6), 915. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland EB, DuBose-Morris R, & Duckett A (2019). Telehealth for the internal medicine resident: A 3-year longitudinal curriculum. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1357633X1989668. 10.1177/1357633X19896683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick JD, & Kirpatrick WK (2016). Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Training Evaluation. Alexandria, VA: ATD Press. [Google Scholar]

- Krupinski E, & Weinstein RS (2013). Telemedicine in an academic center--the Arizona Telemedicine Program. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 19(5), 349–356. 10.1089/tmj.2012.0285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanagnou D, Sicks S, & Hollander JE (2015). Training the next generation of care providers: Focus on telehealth. Healthcare Transformation, 1(1), 52–63. 10.1089/heat.2015.29001-psh [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pourmand A, Ghassemi M, Sumon K, Amini SB, Hood C, & Sikka N (2020). Lack of Telemedicine Training in Academic Medicine: Are We Preparing the Next Generation? Telemedicine and E-Health, tmj.2019.0287. 10.1089/tmj.2019.0287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge C, Hawkins EJ, Bordelon M, & Gustin TS (2020). Telehealth education: An interprofessional online immersion experience in response to COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Education, 59(10), 570–576. 10.3928/01484834-20200921-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, Haydon H, Mehrotra A, Clemensen J, & Caffery LJ (2020). Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 1357633X2091656. 10.1177/1357633X20916567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetten NE, Hagen MG, Nall RW, Anderson KV, Black EW, & Blue AV (2018). Interprofessional collaboration in a transitional care management clinic: A qualitative analysis of health professionals experiences. Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice, 12, 73–77. 10.1016/j.xjep.2018.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, & Chen BY (2015). Curriculum development for medical education: A six-step approach. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach, Third Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press Books. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein RS, Mcneely RA, Holcomb MJ, Doppalapudi L, Sotelo MJ, Lopez AM, … Barker GP (2010). Technologies for interprofessional education: The interprofessional education-distributed “e-classroom-of the future.” Journal of Allied Health, 39(3), 238–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplement 1: Open-Ended Comments Coding Hierarchy

IP 717: Telehealth Teams of the Future Syllabus (updated link for publication will be provided)