Abstract

Introduction

COVID-19 has spread worldwide since its appearance at the end of 2019. In Spain, 99-day long home confinement was set from March 15th 2020. Previous studies about events requiring situations of isolation suggested that mental health problems may occur among the general population and, more specifically, vulnerable groups such as individuals with serious mental illness (SMI). This study aims to assess the psychological effect of confinement in patients with mental illness admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Method

In this longitudinal study, IDER (State-Trait Depression Inventory) and STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) questionnaires were used at two different times (at the beginning and after the lockdown) of the pandemic to evaluate the depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively, in a population of patients who had been previously admitted to the Psychiatry Unit of the Basurto University Hospital.

Results

95 participants completed the IDER questionnaire in the first measurement, with a mean score of 24.56 (SD = 8.18) for state and 23.57 (SD = 8.14) for trait. In the case of STAI, the mean score was 27.86 (SD = 15.19) for the state and 30.49 (SD = 14.71) for the trait. No differences between the first and the second time were found in anxiety and depression levels. People with personality disorders presented high levels of anxiety.

Conclusions

Individuals with a personality disorder showed the highest scores in anxiety and depression. Nevertheless, strict confinement did not affect this population, despite the literature that evidences that the pandemic has worsened people's mental health with SMI.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Serious mental illness, Mental health

Abstract

Introducción

El COVID-19 se ha extendido ampliamente desde su aparición a finales del año 2019. En España se estableció un confinamiento domiciliario que comenzó el 15 de marzo de 2020 y tuvo una duración de 99 días. Estudios previos sobre situaciones que implican aislamiento indican un empeoramiento en la salud mental de la población general, y específicamente en personas con un trastorno mental grave. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar el efecto psicológico del confinamiento en pacientes con trastorno mental grave.

Método

Se emplearon los cuestionarios IDER (State-Trait Depression Inventory) y STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) al inicio del confinamiento y después del mismo, para evaluar síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, respectivamente, en una población de pacientes que habían precisado previamente un ingreso hospitalario en la unidad de hospitalización psiquiátrica en el Hospital universitario de Basurto.

Resultados

En la primera evaluación, 95 participantes completaron el cuestionario IDER, obteniendo una puntuación media de 24,56 (DE = 8,18) para el estado y 23,57 (DE = 8,14) para el rasgo. En el cuestionario STAI se obtuvo una puntuación media de 27,86 (DE = 15,19) para el estado y de 30,49 (DE = 14,71) para el rasgo. No se hallaron diferencias entre los niveles de ansiedad y depresión de las 2 evaluaciones. Los individuos con trastorno de la personalidad presentaron altos niveles de ansiedad.

Conclusiones

Los individuos con trastorno de la personalidad obtuvieron los resultados más altos en ansiedad y depresión. El confinamiento estricto no afectó a esta población, a pesar de la evidencia existente sobre un empeoramiento en la salud mental en pacientes con trastorno mental grave durante la pandemia.

Palabras clave: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Trastorno mental grave, Salud mental

Introduction

COVID-19 has spread rapidly worldwide since its appearance at the end of 2019.1 By January 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, and afterwards characterized as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 2020.2 According to the latest data from the WHO, as of January 5th 2022, more than 290 million people have been infected worldwide and over 5.4 million deaths have been reported.3

When it comes to mental health, a higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms have been noticed among the general population when compared to the prevalence before the pandemic.4 Nevertheless, regional differences existed due to varying outbreak severity, national economy, government preparedness, availability of medical supplies/facilities, and proper dissemination of COVID-related information.4 For instance, in a study that compared mental health outcomes in different countries during the COVID-19 outbreak, Poland proved to be one of the countries with high levels of anxiety, depression and stress, whereas Vietnam had the lowest mean scores in that dimensions.5

When focusing on developing countries, countries with a low number of cases and deaths showed high scores in depression.6 Moreover, the high educational background was associated with more adverse psychiatric symptoms, and family support played a relevant role in symptom reduction.7

In order to contain the infection and prevent the virus from spreading further, government responses were rapidly implemented in most countries. Surprisingly, those stringent measures benefited the physical health of population and their mental health.8 It was found out that countries that waited to implement stringent lockdown measures showed a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms compared to countries that implemented these measures soon,8 as they helped to increase certainty and resilience9, 10 and avoided chronic uncertainty, which is related to begetting anxiety and depressive disorders.11 In addition, as the post-COVID-19 syndrome has been studied, it should be remarked that depressive symptoms have been closely related, even though it still cannot be said that depression is more frequent in patients suffering from this syndrome than in the general population.12

Moreover, the influence of mood disorders in the risk of COVID-19 infection has also been studied, and higher odds of hospitalization and death have been identified in individuals with mood disorders13 since this population is associated with factors -such as economic insecurity, insufficient access to primary preventive health care – that may potent COVID-19 risk.14 Furthermore, symptoms of mood disorders – apathy, abolition, cognitive deficits – may be related with unhealthy behaviors.13

Many precautionary measures have been enacted to fight the pandemic, most of which have been proved to have an impact in physical and mental health during the pandemic: social distancing,15 face mask use,16, 17, 18 lockdown or mobility restrictions.19 In Spain, 99-day long home confinement was set from March 15th 2020 onwards.20

There were no precedents for a confinement of these characteristics in the number of affected people or duration. Previous studies on the health impact of outbreaks of infectious diseases which required situations of isolation, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS),21 Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS),22 and Ebola virus,23 suggested that mental health problems may occur among the general population and, more specifically, vulnerable groups. There is already some evidence of the relevant effect of the pandemic in mental health on different populations around the world,24 and specifically in Spain.25

A significant increase in psychopathology has been reported for healthcare workers worldwide,9, 26 for pregnant women27, 28 as well as for the child and adolescent population29 due to confinement. However, less is known about the effects of the lockdown and isolation in patients who meet criteria for serious mental illness, being understood as a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.11

The aim of this study is to assess the psychological effect of confinement in patients with a serious mental illness who had required a psychiatric admission to an inpatient care unit in a general hospital over the previous two years.

Methods

Study design

An observational study was conducted. A total of 7 interviewers, previously trained through the joint conduct of 5 interviews to standardize the collection and administration of inventories, collected the data by telephone.

The first measurement interval took place between April 1st and May 15th 2020. During this period, the total number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Spain was around 209.465, with 23.521 national deaths attributed to COVID-19.30 Spanish population was in strict confinement, and it was only legal to leave home for fundamental reasons (employment, essential purchases or assistance to pharmacies and medical settings).

A second measurement period was carried out between June 1st and July 31st 2020. Over that period, the total number of cases and deaths from COVID-19 in Spain were 278,782 and 28,434, respectively.31 Home confinement had come to an end, but there were some restrictions in place (related to the use of public transport, the opening and capacity of bars and restaurants, among others) according to the evolution of the epidemiological situation.

This study was approved by the Basurto University Hospital Research Ethics Committee. In compliance with Organic Law 3/2018 of December 5th on protecting personal data and guaranteeing digital rights, personal data was collected and analyzed in a pseudonymized manner using a code assigned to each medical record number. The study is compliant with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) with the changes revised in Fortaleza, Brazil (2013), in the Council of Europe Convention on human rights and biomedicine, and the regulations on biomedical research and personal data protection (Law 14/2017).

Study population

For the present study, all those patients admitted to the Psychiatry Unit of the Basurto University Hospital (HUB) in the two years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic were included. The HUB is a public hospital located in Bilbao, Biscay. It serves a total population of 370,000 inhabitants and has 42 beds for hospitalization of acute psychiatric pathology in adult patients.

The inclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients between 18 and 85 years old; (2) who have had at least one hospital admission lasting more than 24 h in the inpatient service of the HUB between April 1st 2018 and April 1st 2020; (3) diagnosed at discharge with any of the disorders included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5);32 (4) providing active consent to participate in the study.

The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) patients who, between the two interviews, were admitted to a hospitalization unit; (2) patients who, in the first measurement interval, were in a situation of acute psychopathological decompensation according to the latest information collected by their reference clinician; (3) patients with cognitive impairment or intellectual difficulty that make it impossible to understand the administered questionnaire; (4) patients who had abandoned the interview prior to completing at least one of the questionnaires included in the study.

Outcomes

Demographic data (age, sex, employment status), information regarding the lockdown situation (type of residential environment, cohabitants, dependents, strict compliance with quarantine, number of weekly departures from home) and their psychiatric disorder (principal diagnosis included in the discharge report of the last hospital admission using DSM-5 or ICD-10 coding) were collected.

Anxious symptomatology was evaluated through the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). This scale is a psychological inventory that assesses state anxiety and trait anxiety on a 4-point Likert scale. It includes 40 items, with a total administration time of around 15 min. The score ranges from 20 to 80 points for each of the two domains (state anxiety and trait anxiety), where a higher score is equivalent to greater severity in the anxious symptomatology. There are no predefined cut-off points, and each score must be weighted according to demographic and clinical characteristics to obtain the percentile. The questionnaire has been validated in Spanish for the general population.33 Depressive symptomatology was evaluated through the State-Trait Depression Inventory (IDER). It consists of 20 items, with a total administration time of 10 min. The score ranges from 10 to 40 points for each of the two domains (state and trait), where a higher score is equivalent to greater severity of depressive symptoms. It has been validated in Spanish for both the clinical and general populations.34

Statistical analysis

Only the questionnaires in which the participant had given his or her informed consent, and had completed at least one of the neuropsychological tests included in it, were analyzed. The baseline characteristics of the sample were described by mean and standard deviation in the case of quantitative variables; and frequency and percentages in the categorical variables. Outcomes of STAI and IDER inventories were described by mean and standard deviations of the plain score and population percentiles.

Shapiro–Wilk Test was used to verify normality of the sample, and paired student T-test was used to analyze differences obtained between the scales of the two different assessments (time 1 and 2) in the case of normal distribution of the sample. When data did not meet the normality criteria, Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was performed.

Results

In total, 164 participants were contacted, where all the potential responders were included. After exclusion of patients who did not give consent or met other exclusion criteria, the final sample included 95 individuals. Those were patients with pre-pandemic psychiatric diagnosis and need of hospital admission at least once in the last two years. There were no differences between responders and non-responders regarding age, sex and diagnosis at discharge.

The mean age of the final sample was 48.30 years (SD = 1.47). Socio-demographic and clinical variables are detailed in Table 1 . 48 participants were female participants. The group of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders was the most common diagnosis (45.26%) followed by depressive disorders (25.26%).

Table 1.

Description of demographic variables.

| Variables | Data n (%)/mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.30 ± 1.47 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 47 (49.47) |

| Female | 48 (50.53) |

| Diagnosis (ICD-10) | |

| Disorders due to psychoactive substance use (F10-19) | 9 (9.47) |

| Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders (F20-29) | 43 (45.26) |

| Bipolar disorder (F30-31) | 10 (10.53) |

| Depressive disorders (F32-39) | 24 (25.26) |

| Anxiety and stress-related disorders (F40-49) | 3 (3.16) |

| Personality disorders (F60) | 5 (5.26) |

| Other diagnosis | 1 (1.05) |

In Table 2 , variables related to lockdown characteristics have been described. Most interviewed participants (61.05%) lived in their family home, and a majority (68.89%) was living with other family members or their couple. Only 13.68% of the participants were responsible for a dependent person during the confinement. A large part of the sample (92.63%) indicated to respect completely house confinement, and 44.68% were responsible for shopping since the beginning of the confinement.

Table 2.

Description of lockdown variables.

| Household type | |

| Family home | 58 (61.05) |

| Own home | 33 (34.73) |

| Residential center | 3 (3.15) |

| Other (no residence stability, street-living…) | 1 (1.05) |

| Living status | |

| Family/couple | 65 (68.89) |

| Flatmate | 11 (11.83) |

| Alone | 17 (18.28) |

| Responsible for dependent person | |

| Yes | 13 (13.68) |

| No | 82 (86.32) |

| Are you respecting house confinement? | |

| Yes, completely | 88 (92.63) |

| Yes, with some exceptions | 6 (6.32) |

| No answer | 1 (1.05) |

| How many times did you go out in the last week? | |

| Everyday | 31 (32.63) |

| 3–4 times | 23 (24.21) |

| Once or twice | 20 (21.05) |

| Never | 21 (22.11) |

| Employment | |

| Employed, on-site work | 5 (5.38) |

| Employed, telework | 2 (2.15) |

| Employed, temporarily suspended due to pandemic | 7 (7.53) |

| Recently unemployed due to pandemic | 2 (2.15) |

| Unemployed/pensioner | 76 (81.72) |

| No answer | 1 (1.08) |

| Responsible for shopping (food, essential products…) since confinement was stablished | |

| Yes, always | 43 (44.68) |

| Sometimes | 17 (18.09) |

| Never | 35 (37.23) |

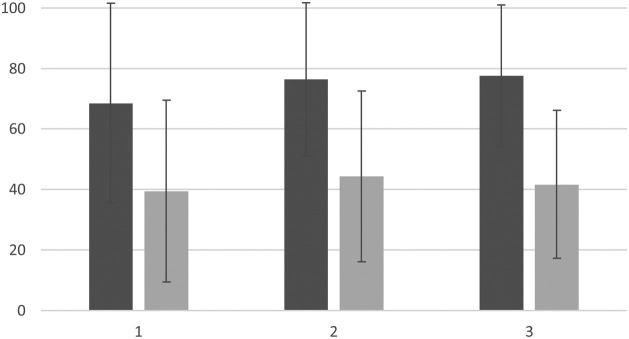

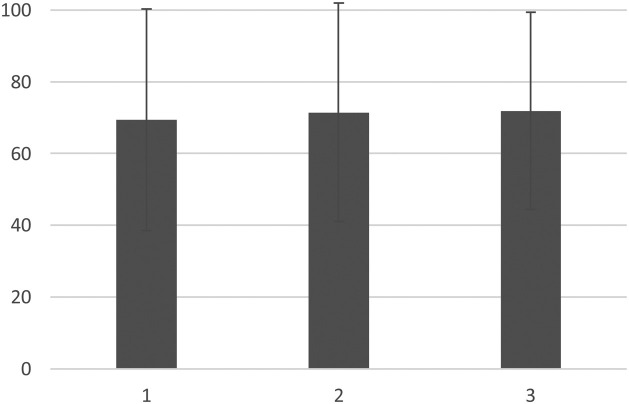

95 participants completed the IDER questionnaire in the first assessment, with a mean score of 23.57 (SD = 8.14) for trait and 24.56 for state (SD = 8.18). This trait score correlates to a 68.52 percentile if it is scaled according to the general Spanish population (where the average score is 17.68) and a 39.44 percentile in the scale of the clinical population. The state punctuation in the first measurement correlates to a 76.41 percentile if it is scaled according to the general Spanish population (where the average score is 16.99) and a 44.34 percentile in the scale of the clinical population. 95 participants completed the STAI questionnaire. In this case, the mean score was 27.86 for the state (71.52 percentile) and 30.49 for the trait (69.45 percentile). These results are exposed in Figure 1, Figure 2 .

Figure 1.

Percentile mean and SD obtained in IDER questionnaire at time 1. 1: Trait. 2: State. 3: State in the time 2. Black: percentiles in general population. Gray: percentiles in clinical population.

Figure 2.

Percentile mean and SD obtained in STAI questionnaire. 1: Trait. 2: state at time 1. 3: state at time 2.

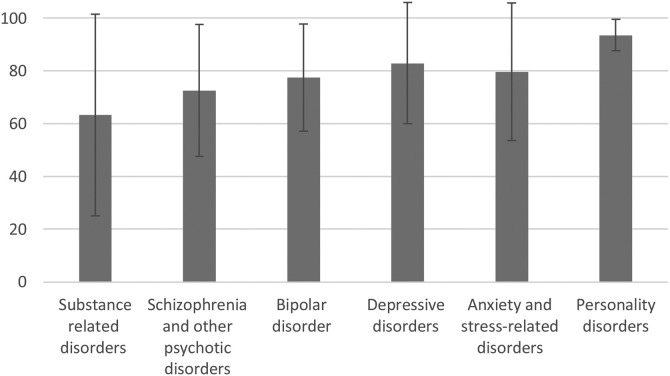

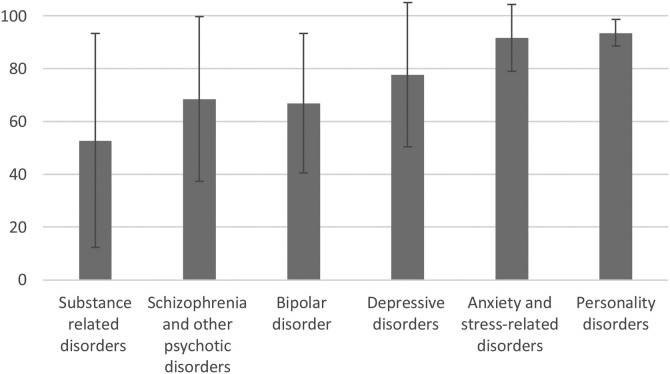

Statistically significant differences were obtained in results of IDER scale (p = 0.038) and STAI sale (p = 0.016) when taking into account the main diagnosis at discharge, results are exposed in Figure 3, Figure 4 . The correction for the rest of the variables analyzed (age, pharmacological treatment, factors related to the situation of confinement) did not offer statistically significant differences.

Figure 3.

IDER questionnaire percentiles at time 1, classified by diagnosis at discharge. Means and SD.

Figure 4.

STAI questionnaire percentiles at time 1, classified by diagnosis at discharge. Mean and SD.

Discussion

Individuals with SMI scored above the 70th percentile of the general population, as expected, showing higher anxiety and depression symptoms rates than the general population. Besides, participants with personality disorders tended to score higher in both anxiety and depression, followed by depressive disorders in the case of depression and by anxiety-related disorders in anxiety assessments. No significant differences were found when comparing assessments between time 1 and 2. Individuals with SMI are not the only population with an increase in psychological symptoms,35 in particular, the Spanish population results in worse depression and anxiety outcomes compared to China population.24 Additional symptoms have been previously reported, for instance, elevated feelings of paranoia36 and isolation,37 self-harm and suicidal ideation.38 Fatigue was more severe in those with a lower quality of life, related to severe depressive symptoms, insomnia, and pain.39 Individuals with SMI are in an especially vulnerable position to suffer from psychiatric symptoms; due to many risk factors40 such as cognitive deficits,41 a poor education,42 severe psychiatric illness episodes and a consequent need of hospitalization.43

A large proportion of the individuals in our study stated that they complied accurately with the confinement rules, and nearly half of them were responsible for shopping during the restrictions. According to the literature, most individuals with SMI expressed interest in preventing COVID-19, which was related to marital status and level of education.44 However, this population was, in general, not as acquainted with COVID-19 and preventive measures as the general population.45 This lack of knowledge was associated with a lower socioeconomic status, level of education, and poor social support. Furthermore, mental disorders have been associated with more worries about COVID-19-related impacts on health and the economy.46

In our sample, patients with bipolar disorder (BD) did experience more depressive symptoms than general population (77th percentile) and placed 4th in the IDER questionnaire score, right after those with a depressive and anxiety disorder. Surprisingly, they coped better than the rest of the subgroups (except substance use disorders) when it comes to anxiety. There is clinical evidence that patients with affective disorders reported higher psychological distress than healthy controls. In contrast to the findings in our research, other studies suggest that individuals with BD experienced more stress and depressive symptoms than individuals with depression. Also stated that men with BD had more symptoms of distress and depression than women.47 Stress and distress during lockdown were related to a longer duration of psychiatric illness, living alone during the lockdown, the habit of smoking,48 and frustration-directly associated with unemployment.49 Loneliness, absence of children, and a passive coping style were associated with a more important manifestation of psychiatric symptoms.50 On the other hand, presence of acute maniac symptoms seemed to be a protective factor.51 Among individuals with affective disorders, 25% had been reported to suffer from sleeping problems,52 even though it is not clear if that is related to stress or a developing acute maniac episode. Particularly, some authors pointed out that in patients with BD, negative life events, such as job loss, bereavement, or personal issues, could worsen not only depressive symptoms but also maniac one.51

Individuals with a depressive disorder pointed high in IDER questionnaire, being second after patients with a personality disorder. They were in third place in the ranking of STAI questionnaire. In a report in the USA about adults with pre-existing depression, most of the studied individuals forecasted that their mental health would deteriorate as physical distancing continued. However, participants coped well during the first months of lockdown, giving an example of the “honeymoon phase” phenomenon, described in acute disasters. Nevertheless, as the COVID-19 pandemic was likely to last months or years, continued follow-up could indicate of worsening mental health in this population.53 As for gender, one study found that men had depressive symptoms to a greater extent than women.47

Outcomes in anxiety and depression of patients with schizophrenia and related disorders also showed an elevated psychopathology (around 70th percentile in both questionnaires) during lockdown. Nevertheless, they happen to deal better with confinement than many other individuals on the sample. Existing evidence indicates that individuals with schizophrenia living in isolation due to a suspected COVID-19 infection were more stressed, anxious, depressed, and had a worse quality of sleep than individuals with schizophrenia who were not quarantined. After the quarantine, this symptomatology continued.54 Living on communal residences during lockdown may have been an important factor in limiting these patients’ increase in depressive, anxious, and stressful symptoms, even though participants still showed higher levels of anxiety relative to healthy controls. They were supported by both their cohabitants and mental health professionals, and on average remained adherent to their treatment and possessed knowledge about the consequences of COVID-19.55

As for anxiety-related disorders, according to literature and to results in this research, these individuals experienced more stress and depression than other populations (90th and 80th percentile, respectively). They also experienced more PTSD symptoms than individuals with affective disorders and the general population. In addition, individuals with anxiety-related disorders had a bigger tendency to self-isolate and to make more active efforts at coping with self-isolation distress. Moreover, due to continuous reports about the pandemic in mass media, fear activation is likely to stay high in anxiety sufferers. During the pandemic, a common recommendation for coping with stress has been to limit one's exposure to news reports. However, even if individuals with self-reported anxiety problems applied this strategy, they inevitably may be more sensitive to information, with subsequent anxious reactions.56

Within the spectrum of personality disorders and the pressure of lockdown, different outcomes could be expected from expecting individuals to react differently to the pressure of lockdown. For example, it would be expected that those with pre-existing borderline/histrionic personality disorders would present more frequently to psychiatric services during lockdown due to an increase of interpersonal conflicts. In contrast, narcissistic and antisocial show a bigger chance of contracting COVID-19, as they could be less likely to follow guidelines and measures imposed during the lockdown. On the other hand, cluster C individuals would be expected to have higher adherence to regulations.57 In our sample, most people included in personality disorder subgroup were suffered specifically from borderline personality disorder (BPD), and as exposed, they obtained the highest scores both in anxiety and depression, maybe due to elevated sensitivity and paranoid preoccupations.

In general, people with pre-existing psychiatric disorders have been more likely to show more severe symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, stress, and insomnia for the first months of the pandemic. Psychiatric patients might have found a reduction in mental health services during the COVID-19 epidemic due to several factors: first, psychiatric patients’ immediate mental health care needs were a lower priority when the incidence of COVID-19 cases rose sharply during the different waves. Second, psychiatric patients were encouraged to avoid visiting the hospital as health services were committed to managing terminally ill patients and cases of COVID-19. Furthermore, the lockdown measures made it difficult for patients to see psychiatrists due to insufficient healthcare resources and fear of contracting COVID-19 in hospitals.58

For these reasons, telemedicine has been an efficient alternative during the pandemic,59 as it opens the possibility to provide an accurate service to patients while diminishing the risk of spreading COVID-19. As for mental health, the efforts to curb the spread of COVID-19 that may result from face-to-face attention and therapy, several centers have used online psychotherapy on video conferencing platforms such as Zoom,60 especially based on internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT), since it is one of the most evidence-based treatment during the pandemic.61 There is evidence that I-CBT can mitigate maladaptive coping behaviors by enhancing abilities to manage stress60 and that it is particularly helpful when treating concrete symptoms like insomnia.62 Thus, online psychotherapy, especially I-CBT, should be considered a treatment option. Other therapies, like mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), help alleviate stress in the clinical population and healthy individuals.63

As the amount of information about the COVID-19 and its consequences in physical and mental health grows exponentially and defeats the initial uncertainty, population's attitude changes toward the virus. It would be interesting to explore if psychiatric patients’ standpoint varies from general populations’. For instance, elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and insomnia could affect perception toward COVID-19 vaccination, resulting in vaccine hesitancy. Hao et al. reported high rates of willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in people with depression and anxiety disorder.64 Results were postulated to be associated with educational level, perceived risk of the virus and confidence in public healthcare system and in government.65 In this context, further study should be performed to obtain data about the population with mental health problemś perception of the pandemic situation in Spain.

In conclusion, the pandemic has been leading to a worsening in the mental health situation of individuals with SMI. Symptoms of anxiety and depression were more ubiquitous in contrast with general population. In this research, individuals with a personality disorder showed the highest scores in anxiety and depression. Nevertheless, no differences were found between the two assessments, so it can be concluded that the strict confinement did not have effect this population, despite the literature that evidences that the pandemic has worsened mental health of people with SMI. Thus, this situation requires a reinforcement of mental health services, including the establishment of online treatments. When it comes to scientific evidence, there is a need to develop long-term follow-up studies, as well as standardizations to generalize the effect of pandemic in people with SMI.

Funding

This research received funding from the OSI Bilbao Basurto Research Commission.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare none.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) [Internet]. Who.int. 2022 [cited 6.1.22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov).

- 3.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) – World Health Organization [Internet]. Who.int. 2022 [cited 5.1.22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?gclid=Cj0KCQjw7MGJBhD-ARIsAMZ0eesjMiAoiau_iEk-616CPVWtErNDSN1hu6TMGslv2w7FlHfb07j7yYEaAg-8EALw_wcB.

- 4.Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M.W., Gill H., Phan L., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang C., Chudzicka-Czupała A., Tee M.L., Núñez M.I.L., Tripp C., Fardin M.A., et al. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci Rep. 2021;11:6481. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85943-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, Tee M, Roy AE, Fardin MA, Srichokchatchawan W, Habib HA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: a study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. PLOS ONE. 2021;16:e0246824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Li S., Xu Q. Family support as a protective factor for attitudes toward social distancing and in preserving positive mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Health Psychol. 2022;27:858–867. doi: 10.1177/1359105320971697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y., Lui L.M.W., Chen-Li D., Liao Y., Mansur R.B., Brietzke E., et al. Government response moderates the mental health impact of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of depression outcomes across countries. J Affect Disord. 2021;290:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tee M.L., Tee C.A., Anlacan J.P., Aligam K.J.G., Reyes P.W.C., Kuruchittham V., et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Hara L., Abdul Rahim H.F., Shi Z. Gender and trust in government modify the association between mental health and stringency of social distancing related public health measures to reduce COVID-19: a global online survey [Internet] Public Global Health. 2020 Available from: http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.07.16.20155200 [cited 16.3.22] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakioğlu F., Korkmaz O., Ercan H. Fear of COVID-19 and positivity: mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty, depression, anxiety, and stress. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2021;19:2369–2382. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00331-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Renaud-Charest O., Lui L.M.W., Eskander S., Ceban F., Ho R., Di Vincenzo J.D., et al. Onset and frequency of depression in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review. J Psychiatric Res. 2021;144:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ceban F., Nogo D., Carvalho I.P., Lee Y., Nasri F., Xiong J., et al. Association between mood disorders and risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:1079. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams E.M., Szefler S.J. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:659–661. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tran B.X., Nguyen H.T., Le H.T., Latkin C.A., Pham H.Q., Vu L.G., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on economic well-being and quality of life of the vietnamese during the national social distancing. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565153. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.565153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C., Chudzicka-Czupała A., Grabowski D., Pan R., Adamus K., Wan X., et al. The association between physical and mental health and face mask use during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison of two countries with different views and practices. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569981. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng S., Shen C., Xia N., Song W., Fan M., Cowling B.J. Rational use of face masks in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:434–436. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung C.C., Lam T.H., Cheng K.K. Mass masking in the COVID-19 epidemic: people need guidance. Lancet. 2020;395:945. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30520-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le H.T., Lai A.J.X., Sun J., Hoang M.T., Vu L.G., Pham H.Q., et al. Anxiety and depression among people under the nationwide partial lockdown in Vietnam. Front Public Health. 2020;8:589359. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.589359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Real Decreto 463/2020, de 14 de marzo, por el que se declara el estado de alarma para la gestión de la situación de crisis sanitaria ocasionada por el COVID-19. BOE n, 67 de 14 Mar 2020.

- 21.Wing Y.K., Leung C.M. Mental health impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome: a prospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2012;18(Suppl. 3):24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong H., Yim H.W., Song Y.-J., Ki M., Min J.-A., Cho J., et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016048. doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisely S., Warren N., McMahon L., Dalais C., Henry I., Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C., López-Núñez M.I., Pan R., Wan X., Tan Y., Xu L., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health in China and Spain: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5:e27818. doi: 10.2196/27818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Fernández L., Romero-Ferreiro V., Padilla S., López-Roldán P.D., Monzó-García M., Rodriguez-Jimenez R. The impact on mental health patients of COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aymerich C., Pedruzo B., Pérez J.L., Laborda M., Herrero J., Blanco J., et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects on health workers’ mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry. 2022;21:1–20. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen L.H., Nguyen L.D., Ninh L.T., Nguyen H.T.T., Nguyen A.D., Dam V.A.T., et al. COVID-19 and delayed antenatal care impaired pregnant women's quality of life and psychological well-being: What supports should be provided? Evidence from Vietnam. J Affect Disord. 2022;298:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.10.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan S., Guan J., Cao L., Wang M., Zhao H., Chen L., et al. Psychological effects caused by COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Asian J Psychiatry. 2021;56:102533. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panda P.K., Gupta J., Chowdhury S.R., Kumar R., Meena A.K., Madaan P., et al. Psychological and behavioral impact of lockdown and quarantine measures for COVID-19 pandemic on children, adolescents and caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Trop Pediatr. 2021;67:fmaa122. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Actualización no 88. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19). 27.04.2020 [Internet]. Sanidad.gob.es. 2022 [cited 25.1.22]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_88_COVID-19.pdf.

- 31.Actualización no 171. Enfermedad por el coronavirus (COVID-19). 27.07.2020 [Internet]. 2022 [cited 25.1.22]. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_171_COVID-19.pdfhttps://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/Actualizacion_171_COVID-19.pdf.

- 32.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2017.

- 33.Buela-Casal G., Guillén-Riquelme A. Short form of the Spanish adaptation of the state-trait anxiety inventory. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2017;17:261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guillot-Valdés M., Guillén-Riquelme A., Buela-Casal G. A meta-analysis of the generalization of the reliability of state/trait depression inventory scores. Psicothema. 2020:476–489. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2020.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iasevoli F., Fornaro M., D’Urso G., Galletta D., Casella C., Paternoster M., et al. Psychological distress in patients with serious mental illness during the COVID-19 outbreak and one-month mass quarantine in Italy. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1054–1056. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720001841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costa M., Pavlo A., Reis G., Ponte K., Davidson L. COVID-19 concerns among persons with mental illness. PS. 2020;71:1188–1190. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jefsen O.H., Rohde C., Nørremark B., Østergaard S.D. COVID-19-related self-harm and suicidality among individuals with mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;142:152–153. doi: 10.1111/acps.13214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou S., Liu Z.-H., Yan X., Wang H., Li Y., Xu X., et al. Prevalence and correlates of fatigue and its association with quality of life among clinically stable older psychiatric patients during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Global Health. 2020;16:119. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00644-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sukut O., Ayhan Balik C.H. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on people with severe mental illness. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57:953–956. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheffield J.M., Karcher N.R., Barch D.M. Cognitive deficits in psychotic disorders: a lifespan perspective. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28:509–533. doi: 10.1007/s11065-018-9388-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tempelaar W.M., Termorshuizen F., MacCabe J.H., Boks M.P.M., Kahn R.S. Educational achievement in psychiatric patients and their siblings: a register-based study in 30 000 individuals in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 2017;47:776–784. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mutlu E., Anıl Yağcıoğlu A.E. Relapse in patients with serious mental disorders during the COVID-19 outbreak: a retrospective chart review from a community mental health center. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021;271:381–383. doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01203-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu J.-H., Li W., Huo X.-N., Jin H.-M., Zhang C.-H., Yun J.-D., et al. The attitude towards preventive measures and knowledge of COVID-19 inpatients with severe mental illness in economically underdeveloped areas of China. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matei V., Pavel A., Giurgiuca A., Roșca A., Sofia A., Duțu I., et al. Knowledge of prevention measures and information about coronavirus in Romanian male patients with severe mental illness and severe alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:2857–2864. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S278471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winkler P., Formanek T., Mlada K., Kagstrom A., Mohrova Z., Mohr P., et al. Increase in prevalence of current mental disorders in the context of COVID-19: analysis of repeated nationwide cross-sectional surveys. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2020;29:e173. doi: 10.1017/S2045796020000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Rheenen T.E., Meyer D., Neill E., Phillipou A., Tan E.J., Toh W.L., et al. Mental health status of individuals with a mood-disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: initial results from the COLLATE project. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Di Nicola M., Dattoli L., Moccia L., Pepe M., Janiri D., Fiorillo A., et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and psychological distress symptoms in patients with affective disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;122:104869. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franchini L., Ragone N., Seghi F., Barbini B., Colombo C. Mental health services for mood disorder outpatients in Milan during COVID-19 outbreak: the experience of the health care providers at San Raffaele hospital. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113317. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orhan M., Korten N., Paans N., de Walle B., Kupka R., van Oppen P., et al. Psychiatric symptoms during the COVID-19 outbreak in older adults with bipolar disorder. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36:892–900. doi: 10.1002/gps.5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carmassi C., Bertelloni C.A., Dell’Oste V., Barberi F.M., Maglio A., Buccianelli B., et al. Tele-psychiatry assessment of post-traumatic stress symptoms in 100 patients with bipolar disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic social-distancing measures in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:580736. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frank A., Fatke B., Frank W., Förstl H., Hölzle P. Depression, dependence and prices of the COVID-19-crisis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamm M.E., Brown P.J., Karp J.F., Lenard E., Cameron F., Dawdani A., et al. Experiences of American older adults with pre-existing depression during the beginnings of the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicity, mixed-methods study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma J., Hua T., Zeng K., Zhong B., Wang G., Liu X. Influence of social isolation caused by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on the psychological characteristics of hospitalized schizophrenia patients: a case-control study. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:411. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burrai J., Roma P., Barchielli B., Biondi S., Cordellieri P., Fraschetti A., et al. Psychological and emotional impact of patients living in psychiatric treatment communities during Covid-19 lockdown in Italy. J Clin Med. 2020;9:E3787. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Asmundson G.J.G., Paluszek M.M., Landry C.A., Rachor G.S., McKay D., Taylor S. Do pre-existing anxiety-related and mood disorders differentially impact COVID-19 stress responses and coping? J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74:102271. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davies M., Hogarth L. The effect of COVID-19 lockdown on psychiatric admissions: role of gender. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e112. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hao F., Tan W., Jiang L., Zhang L., Zhao X., Zou Y., et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case–control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tran B.X., Hoang M.T., Vo L.H., Le H.T., Nguyen T.H., Vu G.T., et al. Telemedicine in the COVID-19 pandemic: motivations for integrated, interconnected, and community-based health delivery in resource-scarce settings? Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:564452. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.564452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho C.S., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49:155–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang M.W.B., Ho R.C.M. Moodle: the cost effective solution for Internet cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) interventions. THC. 2017;25:163–165. doi: 10.3233/THC-161261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soh H.L., Ho R.C., Ho C.S., Tam W.W. Efficacy of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2020;75:315–325. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yeun Y.-R., Kim S.-D. Psychological effects of online-based mindfulness programs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. IJERPH. 2022;19:1624. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hao F., Wang B., Tan W., Husain S.F., McIntyre R.S., Tang X., et al. Attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination and willingness to pay: comparison of people with and without mental disorders in China. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e146. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hudson A., Montelpare W.J. Predictors of vaccine hesitancy: implications for COVID-19 public health messaging. IJERPH. 2021;18:8054. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]