Revised Abstract

Study Aims and Hypotheses:

The Adelante intervention, implemented between 2013–2018, addressed an important syndemic health disparity for Central American immigrant youth approaching or in high school -- the co-occurrence of substance abuse, sex risk (pregnancy, STIs, HIV), and interpersonal violence. Adelante was implemented and evaluated by the Avance Center for the Advancement of Immigrant/Refugee Health, which built on a university-community partnership that has been in place since 2005. Using a tailored, ecological positive youth development (PYD) approach, Adelante employed intervention strategies across ecological levels, including individual, family, peer, and community levels, with the use of social marketing and digital media strategies to link activities under one aspirational identity and support community engagement.

Methods:

Using a Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) approach with multiple community partners involved in the effort, the research assessed changes in co-occurring behavioral outcomes and tested hypotheses concerning relationships between PYD mediators and these outcomes. Multiple methods were used in collaboration with partners to assess intervention inputs and outcomes – detailed implementation process records; pre-post surveys to assess changes in PYD assets, risk behavior knowledge, and prevention skills; a community survey in the intervention and comparison communities (total n=3600) at baseline and two follow-up waves; surveys of a high risk cohort (n=238) at baseline and follow-up, and social marketing campaign surveys (n=1,549) at baseline with two follow-up waves.

Results:

Analysis showed multiple improvements in PYD mediators and risk behavior outcomes, including an overall 70% increase in knowledge and a 15% increase in prevention skills. Preliminary analysis of risk behavior outcomes demonstrated, for example, a significant, inverse effect on reported sexual activity (past 3 months) for both Adelante intervention community and cohort samples. In addition, self-reported exposure to the social marketing campaign was associated with positive effects on multiple outcomes, including drug use risk and violence attitudes, and improvement in violence/sexual risk behavior outcomes in the intervention vs. comparison community.

Conclusions:

There are few models in the literature that provide a roadmap for how to address multiple, related health conditions in marginalized, immigrant communities, even as most health disparities are associated with complex social ecologies. The Adelante intervention adds a useful model of this nature to the evidence base, and provides support for the ecological approach to positive youth development with respect to such communities.

Short Statement:

The Adelante project was a collaboration between a university-based center and multiple community organizations to address the co-occurrence of substance use, sex risk and violence among Central American immigrant youth in a marginalized community setting. The multilevel intervention was designed to increase resilience assets in youth, parents, and community organizations to improve the environment for youth to succeed and avoid risk behavior. Results from this preliminary study show that the model was effective in building resilience across multiple dimensions, changing attitudes about violence and sex risk, and in changing some self-reported risk behaviors.

Introduction/Background

This paper describes an effort to understand and address a health disparity issue for Central American immigrant youth -- the co-occurrence of substance abuse, sex risk and interpersonal violence. Immigrants now constitute 13.7% of the total U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017), and immigrants and their U.S.-born children now number approximately 84.3 million people, or 27% of the overall U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). There are a number of health conditions that are particularly salient for immigrants (CDC, 2018, 2013; Commodore-Mensah et al., 2018; Kirmayer, et al., 2011; Migrants Clinicians Network; WHO, 2018; Yang & Hwang, 2016; Yun et al., 2012), some of which represent distinct health disparities because of their higher prevalence among immigrants compared to the general population. From our perspective, health disparities in general are the outcomes of shared contributing factors that, over time, create “pathways” or trajectories of health and vulnerability that may be unique to specific population groups (Edberg, Cleary & Vyas, 2010; Starfield, 2007). Because these are clusters of health disparities with shared contributing factors, they can be seen as syndemic (Singer & Clair, 2003).

The intervention model outlined in this paper, called Adelante, focuses on Latino immigrant youth from Central America and their particular immigration context. Latinos comprise a significant component of the immigrant population, though of course not all Latinos are immigrants, and the demographic category of Hispanic/Latino encompasses a wide diversity of population groups, including those who pre-date the original settlers from England and non-Iberian Europe. Latinos are also the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, expected to make up 29% of the nation’s population by 2060 (Colby & Ortman, 2015), and Latino youth (ages 10–19) are one of the fastest growing youth segments of the U.S. population. The number of foreign-born Latinos has been declining as immigration from Central and Latin America has slowed (Lopez & Patten, 2015), but Latinos remain the youngest ethnic group in the country: 32% of Latinos are less than 18 years old, and 26% are between 18 and 33 years of age.

Although, in general, Latinos who migrate to the US are likely to be exposed to higher levels of violence and other stressful life experiences than those who are U.S.-born (Porter & Haslam, 2005), those from Central America share a unique set of historical and political circumstances that place them at greater risk for violence exposure. Prior to the 1970s, Central American migration patterns were seasonal and intra-regional (Castles, de Haas, & Miller, 2014). However, by the late 1970s through the 1990s and including the recent waves of unaccompanied youth and now families, migration from this region has reflected U.S. policy, including support for repressive authoritarian regimes, and neoliberal economic policies that contributed to significant economic insecurity. These factors led in part to the wave of Central American migrants fleeing to the U.S. beginning in the late 1970s (Castles, de Haas, & Miller, 2014; ECLAC, 2011; Mahler & Ugrina, 2006). While often fleeing from violence, they faced difficult circumstances in the U.S., one consequence of which was the founding the MS-13 gang, and appropriation of the 18th Street gang, both in Los Angeles. Due to deportations and erratic immigration policy, both gangs were effectively exported to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. In an environment of high poverty, government corruption and instability, as well as proximity to Mexican drug cartels, the two gangs grew precipitously. Now, they are mega-gangs1, and responsible for most of the violence from which youth and families are now fleeing. The plight of these migrants belies the negative stereotypes often presented in the public media. Moreover, in the migration process itself, Central American migrants are often exposed to multiple traumas and adverse circumstances, including physical and sexual violence, witnessing violence, involuntary confinement, extortion, detention, and lack of food and water (Edberg et al., 2018). When they relocate in the U.S., they are frequently faced with legal barriers, economic hardship, discrimination, a hostile political climate, family reunification difficulties, language barriers, and difficulties accessing services – though for some, their situations are still better than what they left (Edberg et al., 2018). This context forms a key element of the vulnerability faced by Central American immigrant youth.

Intervention Community

Langley Park, MD, the community in which the Adelante intervention was developed and implemented through a university-community partnership under the Avance Center for the Advancement of Immigrant/Refugee Health (Avance Center), is a primarily Central American immigrant community facing multiple challenges of the sort just described. It is a community within the Washington, DC metropolitan area that continues to be a top destination for immigrants from Central America. In 1990, foreign-born U.S. residents represented 12% of the population and by 2010, the proportion increased to 22%, a growth of approximately 820% (Singer, 2013), and much of that increase was driven by Central American immigrants. According to U.S. Census data, the 2013 per capita income in Langley Park was approximately $19,126 (in 2017 dollars), about half the Maryland state average (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017).At the local high school, 70% of students were eligible for a free lunch in 2015–16, almost double the state average (Public School Review, data from NCES and the Maryland Department of Education).

While more organizations and services have come into the community in recent years, health services remain minimal. According to a local health assessment done at the time the intervention was implemented (Urban Institute study, Scott et al., 2014), as well as data from the Avance Center, there were no medical specialists, pediatricians, or psychiatrists in the zip codes for Langley Park. The ratios of primary care physicians and nurse practitioners per person, compared to the county at large, were exceedingly low. For example, in Langley Park, the ratio of primary care physicians was 5/100,000 people, compared to 54/100,000 in surrounding Prince George’s County as a whole (Scott et al., 2014), or less than 1/10 the average County access level. In addition, the Urban Institute data showed that nearly 60% of Langley Park residents did not have health insurance. Moreover, about 75% of households are primarily Spanish-speaking (DataUSA, 2017, using data from the American Community Survey), and some residents from Guatemala do not even speak Spanish as a first language, but Mayan languages such as Mam.

Prior Community Collaboration as a Foundation for the Adelante Intervention

Our previous community collaborative work began with the development of knowledge about contributing mechanisms for health disparities that informed the subsequent Adelante intervention. Prior to the formation of the Avance Center, Adelante researchers and partners worked together in the community on a project called SAFER Latinos (2005–2009, funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC), designed to address youth and gang-related violence. In collaboration with community partners, four key domains were identified as mediators for youth violence (family cohesion problems; school-related barriers; lack of community cohesion and efficacy; and the effects of gang presence), and thus targets of the multilevel, community-based SAFER Latinos intervention (Edberg, Cleary, Klevens, Collins, Andrade, Leiva, et al., 2010;Edberg, Cleary, Andrade, Leiva, Bazurto, et al., 2010).

This pilot intervention reduced favorable attitudes towards violence and engagement in violence for young adults in the intervention vs a comparison community (Edberg et al., 2011). Based on intervention study findings, a social ecology of risk was conceptualized in which substance abuse was a “connector” associated with other risks (e.g., familiarity with gangs), nested within a marginalized community context (Cleary, 2014; Edberg et al., 2010).

The role of substance abuse as a risk factor “node” was supported by other literature. Substance abuse plays a key role in contributing to vulnerabilities for negative outcomes including family or partner violence, sexual risk, and youth violence (Edberg, Cleary et al., 2017), and is more prevalent among Latinos who are more acculturated or born in the U.S. (Edberg et al., 2009; Martinez, 2006; Martinez, Eddy & DeGarmo, 2003; Vega & Gil, 1999). Alcohol and drug use can also contribute to interpersonal and gang violence (Edberg et al., 2010) and to a higher risk for contracting HIV/AIDS (Collins et al., 2005).

However, the role of substance abuse acting as a risk factor node is incomplete as a causal explanation. In a community like the intervention site described above, substance use/abuse occurs within a pattern of immigration and associated stressors that includes a concurrent set of contributing factors linked to a cluster of health issues. The level of trauma-related mental health problems, for example, is high among immigrant Central American youth. An Avance Center pilot study of 104 youth from Langley Park who had lived in the US for three or fewer years found that two-thirds had experienced at least one traumatic event during the migration process (Cleary et al., 2017). Another Avance Center pilot study examining transnational contributors to immigrant Latino health disparities (Edberg et al., 2018) documented violence in Central American hometowns, and multiple traumatic exposures and health issues experienced during migration, as well as insecurity related to the current political environment in the U.S. Moreover, an additional, small community definition research effort (Edberg et al., 2015) suggested that residents were well-aware of multiple problems in the community and that community self-image was low.. Yet few interventions or research efforts have captured or addressed broader contextual factors and community dynamics for immigrant Latinos that occur at the community level (see Edberg et al., 2017). Moreover, few substance abuse prevention studies have focused on Latino adolescents (Goldbach, 2011); few studies of family and neighborhood youth violence have focused on Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods (Estrada-Martinez, 2013); and there is a notable lack of sexual health interventions focusing specifically on Latino adolescents (Cardoza et al., 2012).

Program Approach and Theory

Based on the literature, our sustained interaction with and input from community organizations, our own previous research results, and the community context as described, the Avance Center and community partners began development of the Adelante intervention as a means to address the vulnerability cluster of substance abuse and co-occurring heath behavior risks (interpersonal violence, risky sexual behavior) among youth as these issues presented in this Central American immigrant community. Adelante was developed with the understanding that if the substance abuse-related cluster is syndemic in nature, the appropriate intervention must address shared contributing factors as an integrated whole, rather than as analytically distinct factors that happen to occur within a community. It was implemented from 2013–2018.

Adaptation and tailoring of Positive Youth Development theory.

To address the issues described above, Adelante was designed as a multilevel community approach based on what we have called the ecological or integrated stream of Positive Youth Development (PYD) thinking influenced by Richard Lerner and colleagues (Edberg et al., 2017; Lerner et al., 2011; Silbereisen & Lerner 2007; Lerner 2005; Theokas et al., 2005). PYD approaches generally emphasize individual assets or protective factors as the key to prevention of negative behavior; however, in this broader version of PYD a key change mechanism stems from individual interaction with a multilayered ecological web, a person-context relationship that promotes thriving among youth by combining individual-level gains and the harnessing of developmental assets within a community to support the actualization of these gains towards a corresponding reduction in risk behavior (Edberg et al., 2017). Adelante’s PYD foundation focused on four key PYD constructs (called “Cs”): competence, confidence, connection, and contribution. We selected these PYD constructs because it was our shared view that due to the challenges faced by a community like Langley Park, the other two PYD “Cs” (character and caring) were less immediately relevant, and in any case were defined in ways that overlapped with the constructs of confidence and connection.

The Adelante PYD approach was tailored to this Central American immigrant community through an extensive participatory process, in which researchers and community partners collaboratively sought to operationally define the PYD constructs to better reflect community and population characteristics. For example, unlike other community settings where PYD approaches have been implemented, some of the extant socioecological supports for youth (e.g., clubs, organized youth activities) were minimal in this community and would have to be developed or fostered. Definitions, therefore, did not assume such supports. The community collaboration during this developmental phase was significant, as there were few ready models for effective programs that support PYD among Latino youth in a marginalized community context (Lesser, Vacca, & Pineda, 2015).

Incorporation of branding and communications theory to support PYD and intervention goals.

PYD intervention goals were significantly supported by the application of branding theory (Evans & Hastings, 2008), in which behavior change goals are facilitated by association with a unifying identity that increases motivation and values linked to positive, preventive behaviors. For Adelante, branding theory informed the components that used social marketing, digital technologies, and social media outreach to engage youth in the Adelante program identity, which emphasized aspirations for overcoming perceived and real barriers faced by Latino immigrant youth through development of PYD assets and making decisions consistent with Adelante ideals (Andrade et al., 2015; Evans et al., 2015). These communications and engagement activities were intended to connect all Adelante components under one aspirational identity (an affiliation tested in a small study, see Evans et al., 2018).

Implementation of the Program

Theory to practice.

Translation of the tailored PYD theory into program components involved an extensive collaboration between university-based Avance Center faculty, staff and students and the directors and staff of our key community partner, the Maryland Multicultural Youth Center (MMYC), as well as ongoing input from members of the project’s Community Advisory Board (CAB). In order to identify components that would address each selected construct of the PYD theory base, it was necessary to undertake the following steps: 1) Collaboratively review the definitions of each construct and how success should be defined for this community and population – an effort that was also a key part of identifying process and outcome measures; 2) Search available best practice databases for programs or program components that would address the selected PYD constructs and other salient contributing factors, and for any communications/branding efforts implemented for youth at risk; 3) Assess relevant program components successfully employed by our key community partner, the Maryland Multicultural Youth Center, or its parent organization, the Latin American Youth Center (Washington, DC), and; 4) Search available sources and literature for validated scales and measures that might be applicable with respect to program evaluation; this included some scales developed and used for the previous SAFER Latinos intervention. If none of these steps resulted in an acceptable program component or activity, the other option was development of a new component/activity, to be tested during implementation of the intervention.

Because PYD constructs were not yet well-defined, we re-framed them with more precision in order to identify relevant intervention components, activities, and evaluation measures. While the four PYD constructs used in Adelante were initially defined with reference to the literature (e.g., from Bloomquist 2010: Lerner et al. 2005; Zarrett & Lerner 2008), this was followed by operationalizing the selected PYD assets to individual, peer, family, school, and community levels, in order to reflect community circumstances and be useful as guides for intervention components at different levels. These definitions are listed in Supplement 1, available on-line.

Program components.

Specific program components were developed with the PYD person-context framework as a guide. These components included in-person individual-level activities for youth and for parents, multi-level activities involving individuals interacting with larger social contexts (peer, family, school, community engagement and social media/communications), components that were designed to develop and harness community-level structures (Community Advisory Board, Youth Pathways, Drop-in Center), and a case management component for youth and families with especially high need. There was some trialand-error involved, and some activities were discontinued.

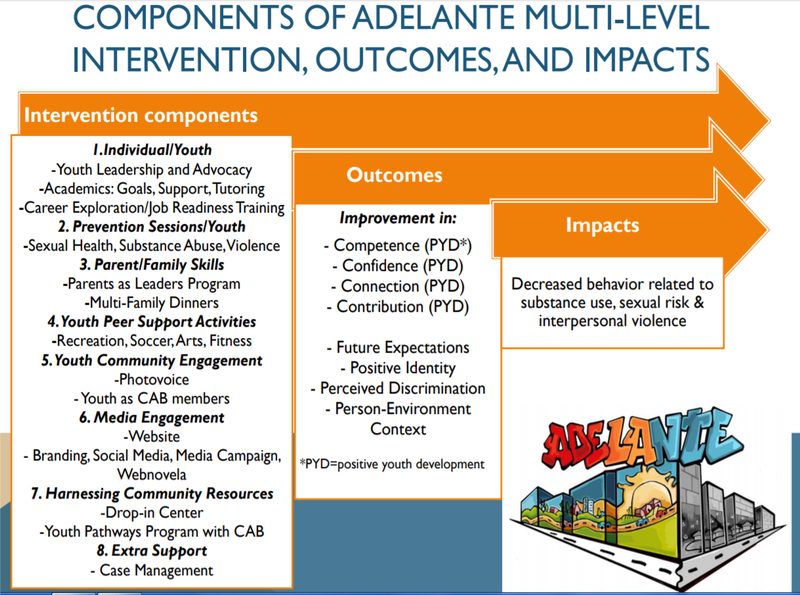

The following is a brief overview of the final set of components/activities in each category. Note that many components overlapped levels – for example, a curriculum-based component designed to increase individual youth knowledge and skills related to prevention of sexual risk behavior also involved peer engagement and support, because the curriculum was delivered in a group setting. In addition, it is important to understand that the components described below were not just a collection of activities, but that they were selected and organized to build PYD and related competencies at multiple ecological levels, and that they were organized under one program brand, whereby activities were framed as part of a coherent movement by participants to overcome barriers and “turn the corner” to succeed and move forward (in Spanish, translated as Adelante – hence the name of the intervention). Figure 1 depicts the overall program logic with activities by category, outcomes (including mediators) and impacts. The program logo is also displayed.

Figure 1.

Adelante Multi-level Intervention Model Components, Outcomes, and Impacts

Specifically, the components and activities were as follows, by category (a more detailed table of components is available in Supplement 1, on-line):

1. Individual-level youth capacity building

Leadership and advocacy.

A curriculum-based activity to promote youth leadership/advocacy addressing the nature of leadership, leadership in the community context, circles of influence, definitions of advocacy, youth as advocates, and advocacy strategies.

Academic support/job readiness.

In partnership with the George Washington University volunteer student group, Puentes, a Saturday morning bilingual academic tutoring group was implemented that served both middle and high school students in Langley Park to provide academic support and tutoring. In addition, job readiness/career training activities were implemented for youth and adults, including small business management. For program youth, the Reaching Excellence program was used to promote academic goal-setting and achievement.

2. Individual-level prevention information and skills for youth:

Sexual health.

For this component, we used two curricula: ¡Cuídate!, a culturally-based group intervention focused on education and skills to reduce HIV sexual risk behavior (developed by ETR, at www.etr.org), and SHAPE (Sexual Health Advocacy through Peer Education, developed by Planned Parenthood and Brown University). ¡Cuídate! and SHAPE were combined to train youth in content, skills, and the ability to serve as peer educators.

Substance abuse prevention.

This component utilized two curricula: Storytelling Powerbook (from the WHEEL Council, www.wheelcouncil.org) and Brain Power (from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, at www.drugabuse.gov). Storytelling PowerBook focused on narrative examples and exploration of substance abuse impacts, while Brain Power focused on the brain and nervous system, drug use impacts and resistance skills.

Violence prevention.

As part of the ¡Cuídate! and SHAPE curricula, selected sessions focused on interpersonal violence knowledge, consent, and prevention skills through roleplaying.

3. Parent/family skills building and cohesion:

Parents as Leaders.

This parent-oriented training (Adapted from the Padres Comprometidos curriculum, National Council of La Raza, www.unidosus.org) was intended to help parents advocate for and promote better policies/practices to improve their children’s education.

Family dinners.

A series of 10 dinner meals were held with Adelante youth and their parents/families, focusing on improving parenting skills to reduce risk factors for substance use and problem behaviors, provide ecological support for positive behaviors, and increase communication capabilities between youth and parents.

4. Peer social support (youth):

Recreational and summer activities.

A number of unique cultural and recreational activities were offered to youth program participants over the course of the intervention, including arts and performance, dance (“Move this World”), summer soccer, and softball for girls. The soccer activity also incorporated discussions of sexual health and community activism, and the softball program included mentoring and discussions of Latina history, skill building, and empowerment.

5. Youth community engagement:

Photovoice.

Youth were trained to use cameras to highlight positive aspects of their community and (negative) aspects that they would like to see changed (see Cubilla-Batista et al., 2017). Photos were exhibited publicly and the youth photographers were present at the exhibit to explain their photos.

Youth membership on the Community Advisory Board (CAB).

Several youth involved in the Adelante program also became members of the CAB and in that role participated in CAB meetings to offer their views on youth needs and planned activities.

6. Engagement through social media and communication:

Website.

The project website (during project operation, linked through www.avancegw.org), was used as an overall information source and site for posting updates, photos, and activities.

Brand development.

Early in the implementation of Adelante, formative research was conducted with youth to identify key elements of an Adelante brand that would be associated with program activities and desired outcomes (Evans et al., 2015; Evans et al., 2018). The brand aimed to position Adelante involvement as a way to rise above challenges faced by these youth and to succeed. The logo itself (see Figure 1) came from youth focus groups in which the goal of “turning the corner” was repeatedly voiced.

Webnovela.

Program youth, with advice and support from MMYC and research staff, developed an innovative webnovela series, available on YouTube, called Victor and Erika (V&E) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=893xP1cSnM0). The V&E webnovela is a six-episode, webbased series that follows the struggles, choices and successes in the lives of two immigrant Latino teenagers living in Langley Park.

Social marketing campaign.

Social marketing was employed to augment the Adelante in-person program’s impact on Latino adolescent attitudes, norms, and prevention behaviors associated with the program brand. The 12-month campaign, launched in August of 2015, included print ads and posters throughout the community; social media promotion with prevention messaging, videos, and contests; text messaging with prevention messages and resource information; and blog posts (see Andrade et al., 2018a; Evans et al., 2019; Barrett et al., 2017).

Social media engagement.

The Adelante program established a Facebook fan page, and the Adelante social marketing campaign utilized this platform for a portion of the campaign’s activities. The Facebook fan page was used extensively for program communication, interactive activities, information dissemination related to the target health disparity issues, and, importantly, to increase youth engagement (Barrett et al., 2017).

7. Harnessing community organizations as resources:

The MMYC Drop-in Center.

The primary community partner, MMYC, had offices in Langley Park, which were the site for some program activities, and also served as a drop-in center for community members to access program staff and related support services such as immigration assistance and counseling.

Youth Pathways.

This component, not implemented as fully as planned during the intervention period, was an attempt to link youth who gained individual capacities through other Adelante components to organizations and even businesses in or near the community that might use their new skills, as interns or even paid employees.

8. Extra support for youth and families at higher risk:

Case management (for higher risk youth and families).

Case management was implemented for youth and parent/guardians who expressed extensive needs. Case management interventions were time intensive, often difficult, and sought to link youth/families to services if possible, provide ongoing support, reduce risk factors and behaviors, and increase PYD assets and capabilities for youth and parents. Case management recipients typically participated in other Adelante activities as well, and then participated in the cohort study described below.

These intervention components were provided at multiple community locations, including the MMYC drop-in center, the “Casita” (a small building in one apartment complex that was dedicated to the Adelante project via an agreement with the apartment management company), the Langley Park Community Center, recreational fields, and other community sites. Social media engagement occurred primarily through the Adelante Facebook fan page, and the social marketing campaign messages were delivered via social media, online, and using outdoor advertising and print media at multiple community sites.

Documenting Intervention Delivery

Because an important goal was to improve the evidence base with respect to multi-level, community prevention efforts directed to risk behaviors among Latino immigrant youth, and thus to document the intervention so that it could be replicated and refined, the process data effort was assigned a high priority. The Adelante team developed and implemented a range of process and short-term outcome tracking procedures and metrics. We used the Efforts to Outcomes (ETO) software (https://www.socialsolutions.com/software/eto/) for tracking inputs, intervention delivery, program reach and intensity, and short-term outcomes. The amount of data collected and degree of follow-up with participants were then categorized to reflect the highest level of intensity to the lowest. For example, the highest level of intensity (Level 1) included multiple forms of data from case records, while the lowest level (Level 5) included only minimal data on, for example, numbers of materials (e.g., flyers) distributed where it was not feasible to collect more extensive data. The specific activity categories were: Level 1- case management; Level 2 - sequential curriculum-based activities with a continuous cohort; Level 3 - sequential non-curriculum based activities, not necessarily a continuous cohort; Level 4 – ongoing, non-sequential, non-cohort activities (e.g., regular academic support hours); and Level 5 – activities or events (e.g., health fairs), not targeted to specific individuals or groups. Pre-post tests were conducted for sequential, cohort-based activities – focused on risk behavior prevention content and PYD assets addressed. Case management data included case notes, case management hours, topics, and referrals.

These extensive process evaluation data were used to develop an intervention exposure measure.

Data Collection and Analysis

The Adelante evaluation encompassed multiple forms of data collection, including pre-post surveys to assess short-term changes in PYD assets, risk behavior knowledge, and prevention skills; a community survey in the intervention and comparison communities (total n=3,600) at baseline and two follow-up waves to assess PYD, attitude and behavior changes; surveys of a high risk cohort (n=238) of youth-parent dyads at baseline and follow-up; and social marketing campaign surveys (n=1,549) at baseline with two follow-up waves. The comparison community for both the community survey and social marketing campaign survey was Culmore, Virginia, a concentrated Central American immigrant community also located in the Washington, DC metropolitan area, but in a different state. These data collection efforts are briefly described below to show the rigor and breadth of information gathered.

Pre-Post Surveys for Short-Term Outcomes

Brief surveys were conducted for all program components rated at Level 2, which, as noted, were curriculum-based and delivered sequentially to a continuous cohort. The pre-post surveys for these components were aligned with the PYD and other competencies planned for each component, and included both PYD and content assessment. PYD assessments were also linked to measurement definitions outlined in Supplement 2.

Community-level Study

Surveys were administered In Langley Park (intervention community) and Culmore (comparison community) at baseline (in 2012), with follow-up waves in 2014 and 2016. Each wave included a sample of 1,200 youth (ages 12–17) and young adults (18–24), for a total sample of 3,600 participants, based on a randomized two-stage cluster sample methodology. Community surveys used a repeated cross-sectional design, so difference-in-differences analyses were used (Bertrand, Duflo & Mullainathan, 2004) to assess significant changes in PYD, attitude, and behavioral outcomes. The survey instrument included measures of PYD constructs (confidence, connection, competence, contribution) at multiple social-ecological levels; attitudes, perceived risk, and self-reported substance use, sexual risk, and violence behaviors; perceived social support (emotional and instrumental); future expectations and aspirations; acculturation and acculturative stress; multicultural efficacy; religion/spirituality, depression; stressful life events; and socio-demographic information (details of measures described elsewhere). The young adult survey was similar to the youth survey, but included age-appropriate adjustments, such as items related to career pursuit instead of career readiness (competence-workforce). All measures were standardized across surveys, with high internal consistency and reliability (alphas >0.80)

Cohort Study

As described above, the Adelante case-management component enrolled a total of 238 higher risk parent-youth dyads in three sequential cohort groups. Case management was provided to participants for an average of 18 months per group – in addition to regular Adelante program activities. For each cohort group, we administered baseline and two follow-up surveys for youth and baseline and follow-up surveys for parents. The cohort youth survey included the same measures as the community survey. The parent survey was abbreviated and focused only on PYD constructs relevant to parents. Of the baseline youth sample, 80% (n=190) of youth completed one follow-up and 176 completed two follow-up surveys for an overall retention rate of 74%. For the cohort study, drawing from the process data, we developed a participant exposure dose measure for PYD constructs based on the frequency (0–8), duration (16 hours), and intensity (27%−87% of time) of PYD covered per intervention activity.

Social Marketing Campaign Study

The social marketing campaign was evaluated for effects on Adelante program outcomes, including PYD variables. Repeated cross-sectional surveys were conducted pre, mid, and post-campaign to evaluate campaign exposure and changes in perceptions and PYD outcomes. Results in Langley Park were compared to those in Culmore, VA, the comparison community. The sample consisted of 1,549 Latino and immigrant youth (ages 12–17) in the intervention and comparison communities. Surveys measured exposure to traditional media, online, and social media use; self-reported exposure to campaign promotions; receptivity to Adelante messages; PYD constructs, using validated scales; and risk behavior attitudes/perceptions – perceived substance use risk, sexual risk taking attitudes, and proviolence attitudes. These outcomes were regressed on campaign exposure to examine doseresponse effects of the Adelante campaign over time, and outcomes were compared between the two communities.

Results

Selected results of the evaluation data analysis are briefly summarized below in sections corresponding to the type of data collected. For consistency, survey results will focus on the data collected from youth samples (ages 12–17). PYD constructs are italicized to distinguish them from other measures.

Short-term Outcomes -- Adelante PYD and Knowledge/Skill Changes

Adelante in-person activity pre-post tests indicated significant improvement in PYD constructs by program. Examples of change related to specific program components include the following: For the sexual health (Cuidate) program, results among those that completed (n=9) the pre- (M=7.1, SD=2.13) and post-test (M=8.0, SD=2.4) indicate a significant increase in knowledge (paired t-test diff=0.9, t-value=1.42, effect size=0.41, p=0.184). For the Family Dinners, increases among youth (n=7) were observed for PYD constructs of confidence (+8.99%), connection to family (+6.10%), and family competence (+7.62%). Parents participating in the Parents as Leaders (PAL) component (n=12) improved with respect to PYD constructs of confidence (pre: M=19.92, SD=6.0; post: M=21.17, SD=6.4; paired t-test diff=1.25, t-value=0.72, effect size=0.21, p=0.49), connection to school (pre: M=16.17, SD=4.9; post: M=19.75, SD=5.9; paired t-test diff=3.6, t-value=2.27, effect size=0.65, p<0.045), and contribution to school (pre: M=15.25, SD=4.6; post: M=19.67, SD=5.9; paired t-test diff=4.42, tvalue=2.94, effect size=0.85, p<0.013).

Cohort Study Results (Youth)

Youth cohort participants were largely (57%) male, and from El Salvador (40%), Guatemala (37%), and Honduras (22%). Most (69%) had been in the U.S. three years or less, and 28% were born in the U.S. Correlational analysis of baseline cohort youth survey data (n=238) indicated significant patterns of PYD and other personal characteristics prior to intervention involvement. Acculturative stress, not surprisingly, was inversely related to school competence (r = −0.087, p=0.18) and positively related to family competence (r = 0.18, p=0.005). Multicultural efficacy (feeling confident about interacting in multiple cultural spheres), for example, was significantly correlated with several other positive characteristics that could support resilience, including confidence (r = 0.34, p<0.0001), connection to social groups (r = 0.46, p<0.0001), and school competence (r = 0.25, p<0.0001). Higher future expectations was significantly related to connection to school (r = 0.38, p<0.0001) and confidence (r = 0.34, p<0.0001). This was useful information as the Adelante intervention was intended to build on these and other assets.

Using the measure of exposure (EXP: 54% of youth), to any Adelante intervention, we compared changes in PYD constructs over time after adjusting for gender, age, U.S.- born status, years in the U.S., and education level to those with no exposure (NEXP) to the intervention. Results indicate an increase in competence in civic action (EXP: M=27.73, SE=1.12; NEXP: M=24.14, SE=1.00; p<.013), greater connection to the community (EXP: M=12.17, SE=0.28; NEXP: M=11.67, SE=0.22; p=0.16), and an increase in contribution (EXP: M=27.17, SE=1.17; NEXP: M=25.89, SE=1.56; p=0.22). Preliminary analysis of intervention risk behavior outcomes demonstrated an inverse effect on reported sexual activity during the past 3 months for the exposed cohort (EXP: M=0.73, SE=0.15; NEXP: M=1.02, SE=0.14; p=0.17) compared to non-exposed; in other words a higher exposure to the Adelante intervention and intensive case management reduced reported risky sexual behaviors, although not statistically significant.

Community-level Study Results (Youth)

The following are selected results across the three waves of data. Means (M; Standard Error SE) are adjusted for language, gender, age, U.S.- born status, years in the U.S., and education level. Results indicate significantly higher adjusted mean levels in Langley Park (LP) after implementation of the intervention versus the comparison community, Culmore (C), with respect to the PYD constructs of confidence (LP: M=3.89, SE=0.02; C: M=3.74, SE=0.03; p<.0001), connection to school (LP: M=3.94, SE=0.02; C: M=3.82, SE=0.03; p<.003), and school competence (LP: M=3.82, SE=0.02; C: M=3.60, SE=0.04; p<.0001), as well as multicultural efficacy (LP: M=33.01, SE=0.39; C: M=30.10, SE=0.58; p<.0001), future expectations (LP: M=42.89, SE=0.60; C: M=39.93, SE=0.90; p<.005), friend instrumental support (LP: M=17.01, SE=0.14; C: M=16.37, SE=0.21; p<.011) and school instrumental support (LP: M=15.30, SE=0.15; C: M=14.55, SE=0.22; p<.0045). However, these outcomes were attenuated in the final survey period, possibly due to reductions in exposure as the intervention closed down in the final year. Selected results also indicate lower adjusted mean levels of depression (LP: M=17.41, SE=0.29; C: M=18.82, SE=0.42; p<.0053) in Langley Park versus Culmore, suggesting a possible and important intervention effect that needs further exploration. Preliminary analysis of intervention risk behavior outcomes also demonstrated a significant, inverse effect on the reported mean number of drugs used during the past year for the Adelante intervention community sample (LP: M=0.34, SE=0.10; C: M=0.56, SE=0.16; p<.019), suggesting that higher exposure to the Adelante intervention reduced reported risky substance use behaviors. No significant differences by community were found for other measures.

Social Marketing Campaign Study Results (Youth)

Analysis showed positive effects of self-reported campaign exposure on multiple outcomes, with some exceptions. In the Adelante intervention community, there was improvement in violence and sexual risk attitudinal outcomes vs. the comparison community between study waves 1–3. However, results were mixed regarding attitudes towards substance use (perceived risk). While higher perceived risks of regular drug use were indeed associated with greater exposure to Adelante ads, the overall perceived risks of both occasional and regular drug use were lower in the intervention vs. comparison community – a result that needs further exploration but could be an iatrogenic effect or due to other factors (see Evans et al., 2019).

Summary and Discussion

As an ecological, community collaborative approach tailored to the circumstances of a Central American immigrant community that faces multiple barriers and levels of marginalization, the Adelante intervention aimed to promote an interaction between “person” components that build individual assets for youth, parents, and other adults and “environment” components that establish linkages between these capacity-building activities and community resources that can help foster the development and manifestation of those assets (i.e., thriving) and thus improve attitudinal and behavioural outcomes/impacts (Edberg et al., 2017).This approach follows the interpretation of Positive Youth Development theory outlined earlier in this article. The individual and family capacity building components were designed to build specific competencies in multiple areas including communication skills, knowledge concerning substance abuse, sex risk, violence prevention, advocacy skills, leadership skills and school competency, and to build positive connections to family, peers and school. Community activities were designed to build community connections, community leadership/advocacy skills, youth competencies regarding community engagement, and increased capabilities among community adults and organizations to foster youth development. The Adelante intervention uniquely combined these components with branding and social media activities intended to strengthen the attitude and behavior change effects through the association of all activities with a community-generated positive identity and by amplifying participation and involvement through highly salient communication channels.

The results of this model are promising. Exposure to the Adelante intervention was associated with very positive short-term outcomes within multiple components and across multiple domains, with selected positive longer-term impacts also seen in in the broader cohort and community surveys. We experienced some challenges with the community survey data and results (repeated cross-sectional surveys) in terms of responses (e.g., missing data) and specific exposure and outcome items that were likely due to transience and other factors related to the social ecology of the community, including follow-up participation hampered by an increasingly difficult immigration climate. These are issues for which innovative solutions will need to be explored in further research. A more detailed discussion of evaluation instruments used for the cohort data and community survey will be presented in a separate paper, along with more comprehensive results, but general results as reported here were positive. Moreover, the branding and social media components demonstrated substantial additional results in terms of change in hypothesized mediating PYD constructs and in attitudes and perceptions of risk. Clearly, the in-person intervention components benefited from the complementary activities intended to engage youth in the Adelante brand, prevention messages, and digital Adelante interaction.

One of the key goals of the intervention was to develop and test a model that was substantially more ecological in its approach than most of the available intervention models, in line with the whole-community nature of contributing factors and a cluster of risk behaviors. As noted earlier in the paper, the rationale for this goal was that prevention programming in communities with multiple needs and syndemic health conditions should not be narrowly targeted, because there are too many significant contributing factors that interact. This is not a new or unique conclusion. The problem is that there are not enough models documented in the literature that provide a roadmap for how to address such multiple, related health conditions in these kinds of circumstances, even as most health disparities are associated with such complex social ecologies. The Adelante program as described does target multiple health risks and contributing factors within the context of the intervention community as an integrated effort, and in doing so seeks to develop a “fabric of resilience” that will help youth avoid the risk behaviors of concern. Adelante therefore adds a useful model of this nature to the evidence base, and provides support for the community collaborative, ecological approach to Positive Youth Development in marginalized communities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We also want to acknowledge staff members Nicole D Barrett, Idalina Batista-Cubilla, Ryan Snead, Ivonne Rivera, Daniela Dietz-Chavez, Lauren Simmons, Elizabeth Freedman, Emily Putzer, and Carlos Soles, as well as the Maryland Multicultural Youth Center staff, and all the participating families, youth and community members/organizations.

The research discussed herein was supported by grant #1P20MD6898, from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD).

Footnotes

Referring here to gangs that are distributed across entire countries and even transnationally, with large numbers of members.

REFERENCES:

- Andrade EL, Evans WD, Edberg MC, Cleary SD, Villalba R (2015).Victor and Erika webvonela: An innovative generation@ audience engagement strategy for prevention. Journal of Health Communication 20(12):1465–72. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade EL, Evans WD, Barrett ND, Cleary SD, Edberg MC, Alvayero RD, Kierstead EC, Beltran A (2018). Development of the place-based Adelante social marketing campaign for prevention of substance use, sexual risk and violence among Latino immigrant youth. Health Education Research 33(2):125–144. doi: 10.1093/her/cyx076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade EL, Cubilla IB, Simmons LK, Sojo-Lara G, Cleary SD, Edberg MC (2015). Where PYD meets CBPR: A photovoice program for Latino immigrant youth. Journal of Youth Development 10(2):55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade EL, Evans WD, Barrett ND, Edberg MC, Cleary SD (2018b). Exploring strategies to increase Latino immigrant youth engagement in health promotion using social media. JMIR Public Health Surveillance 4(4): e71. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.9332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett ND, Villalba RO, Andrade EL, Beltran A, Evans WD. (2017). Adelante Ambassadors: Using digital media to facilitate community engagement and risk prevention for Latino youth. Journal of Youth Development 20(4). 10.5195/jyd.2017.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in differences estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119(1): 249–275. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist K (2010). Participation in Positive Youth Development programs and 4H: Assessing the impact on self-image in young people Dissertation. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoza VJ, Documét PI, Fryer CS, Gold MA, and Butler III J (2012). Sexual health behavior interventions for U.S. Latino Adolescents: A review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 25(2): 136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castles S, de Haas H, and Miller MM (2014). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world (5th ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Yellow Book 2018. Accessed November 1, 2018, at https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-totravel/hepatitis-b)

- Cleary SD (2014). Que Esta Pasando? Trends in substance use among Latino youth. Paper presented at Avance Center First Annual Latino Health Disparities Conference, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary SD, Snead R, Dietz-Chavez D, Rivera I, Edberg MC (2017). Immigrant trauma and mental health outcomes among Latino youth. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 20(5):1053–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0673-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SL and Ortman JM (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. population: 2014 to 2060. Available at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf (Accessed June 12, 2018) United States Census Bureau, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, and Klein DJ (2005). Isolating the nexus of substance use, violence and sexual risk for HIV infection among young adults in the United States. AIDS & Behavior 9: 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commodore-Mensah Y, Selvin E, Aboagye J, Turkson-Ocran RA, Li X, Himmelfarb CD, Ahima RS, and Cooper LA. (2018). Hypertension, overweight/obesity and diabetes among immigrants in the United States: An analysis of the 2010–2016 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health 18:773, 10.1186/s12889-018-5683-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubilla-Batista I, Andrade EL, Cleary SD, Edberg MC, Evans WD, Simmons LK, Sojo-Lara G (2017). Picturing Adelante: Latino youth participate in CBPR using place-based photovoice. Social Marketing Quarterly 23(1):18–35. 10.1177/1524500416656586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DataUSA (2017), using data from the American Community Survey, at https://datausa.io/profile/geo/langley-park-md/. Accessed June 4, 2019.

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (2011). Social panorama of Latin America 2011. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC. [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Benavides J, Rivera I, Shaikh H, and Mattiola R (October, 2018). Trauma and other health determinants among recent Central American immigrants: Implications for youth and young adults.” NEOS 10(2): 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Collins E, Harris M, McLendon H, and Santucci P (2009). Patterns of HIV/AIDS, STI, substance abuse and hepatitis risk among selected samples of Latino and African-American youth in Washington, DC. Journal of Youth Studies, 12, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Edberg MC, Cleary SD, Andrade EL, Evans WD, Simmons LK, and Batista I (2017). Applying ecological Positive Youth Development theory to address co-occurring health disparities among immigrant Latino youth. Health Promotion Practice, 18 (4): 488–496. Published on line April 18, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Cleary S, Vyas A (2010). A trajectory model for understanding and assessing health disparities in immigrant/refugee communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 13(3):576–84. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Cleary SD, Klevens J, Collins E, Leiva R, Bazurto M, Calderon M (2010). The SAFER Latinos project: Addressing a community ecology underlying Latino youth violence. Journal of Primary Prevention, 31, 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edberg M, Cleary S, Andrade E, Montero L 2011. Final report, SAFER Latinos: Primary prevention addressing modifiable community factors for Latino youth violence. Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Martínez LM, Caldwell CH, Schulz AJ, Diez-Roux AV, and Pedraza S (2013). Family environment, neighborhood structures, and violent behaviors among Latino, Black, and White adolescents. Youth & Society 45, 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, Andrade E, Villaba R, Cubilla I, Edberg M (2015). Turning the corner: Design and testing of the Adelante health promotion brand for Latino youth. Social Marketing Quarterly 22(1):19–33. DOI: 10.1177/1524500415614838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, Andrade E, Barrett N, Cleary SD, Snider J, Edberg M (2018). The mediating effect of Adelante brand equity on Latino immigrant positive youth development outcomes. Journal of Health Communication 23(7): 606–613. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1496205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, Andrade EL, Barrett ND, Snider J, Cleary SD, Edberg MC (2019). Outcomes of the Adelante community social marketing campaign for Latino youth. Health Education Research cyz016. doi: 10.1093/her/cyz016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, and Hastings G (Eds.) (2008). Public Health Branding: Applying Marketing for Social Change. Oxford University Press. London, United Kingdom. ISBN 9780199237135. [Google Scholar]

- Goldbach JT, Thompson SJ, and Holleran-Steiker LK (2011). Special considerations for substance abuse interventions with Latino youth. The Prevention Researcher, 18(2), 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Lavanya Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder AG, Guzder J, Hassan G, Rousseau C, and Pottie K (2011). Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Canadian Medical Association Journal 183(12): E959–E967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (2005). Promoting positive youth development: Theoretical and empirical bases. White paper prepared for a Workshop on the Science of Adolescent Health and Development, National Research Council, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lerner J, Almerigi JB, Theokas C, Phelps E, Gestsdottir S, Naudeau S, Jelicic H, Alberts A, Ma L, Smith LM, Bobek D, Richman-Raphael D, Simpson I, DiDenti C, and von Eye A (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 17–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, and Lerner JV (2011). The positive development of youth: Report of the findings from the first seven years of the 4-H study on positive youth development. Medford, MA: Tufts University Institute for Applied Research in Positive Youth Development and the National 4-H Council. [Google Scholar]

- Lesser J, Vacca J, and Pineda D (2015) Promoting the positive development of Latino youth in an alternative school setting: A culturally relevant trauma-informed intervention. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 36(5): 388–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López G and Patten E (2015). The impact of slowing Immigration: Foreign-born share falls among 14 largest U.S. Hispanic origin groups. Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler S, and Ugrina D (2006). Central America: Crossroads of the Americas. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-america-crossroads-americas

- Martinez CR Jr. (2006). Effects of differential family acculturation on Latino adolescent substance abuse. Family Problems, 55, 306–317. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR Jr, Eddy JM, and DeGarmo DS (2003). Preventing substance use among Latino youth. In Bukoski WK & Sloboda Z (Eds.), Handbook of drug abuse prevention: Theory, science and practice (365–380). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Migrants Clinicians Network, at https://www.migrantclinician.org/issues/migrant-info/healthproblems.html, accessed 10/30/18.

- Porter M, and Haslam N (2005) Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a metaanalysis. JAMA 294: 602–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public School Review, using data from the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES) and the Maryland Department of Education, at https://www.publicschoolreview.com/high-point-high-school-profile. Accessed June 3, 2019.

- Sampson RJ (2003). The neighborhood context of well-being. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 46(3 Supplement): S53–S64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, MacDonald G, Collazos J, Levinger B, Leighton E, and Ball J (2014). From cradle to career: The multiple challenges facing immigrant families in Langley Park Promise Neighborhood. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Silbereisen RK, and Lerner RM (2007). Approaches to positive youth development. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, and Clair S. (2003). Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17: 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B (2007). Pathways of Influence on Equity in Health. Social Science and Medicine 64:1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theokas C, Almerigi JB, Lerner RM, Dowling EM, Benson PL, Scales PC, and von Eye A (2005). Conceptualizing and modeling individual and ecological asset components of thriving in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). State and County QuickFacts. Accessed May, 2019 at https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/langleyparkcdpmaryland.

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2017). American community survey. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs.html

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). Current Population Survey (CPS). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps.html

- Vega WA, Gil AG. (1999). A model for explaining drug use behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Drugs & Society 14(1–2):57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang PQ and Hwang SH (2016). Explaining immigrant health service utilization: A theoretical framework. Sage Creative Commons April-June 2016: 1–15. DOI: 10.1177/2158244016648137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yun K, Fuentes-Afflick E, and Desai MM (2012). Prevalence of chronic disease and insurance coverage among refugees in the United States.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 14(6): 933–940. 10.1007/s10903-012-9618-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarett N, and Lerner RM (February, 2008). Ways to promote the positive development of children and youth. Research-to-Results Brief. Washington, DC: Child Trends. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.