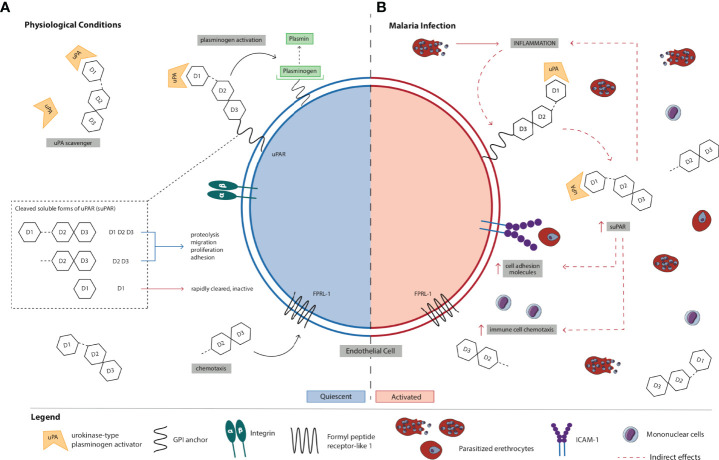

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the (A) normal physiological role of suPAR in inflammation and immune activation vs. (B) proposed mechanism of action of suPAR in the pathogenesis of severe malaria. (A) uPAR is a three-domain (D1, D2, and D3) GPI-anchored protein expressed on the cell surface of immune, endothelial, epithelial, and smooth muscle cells. Full-length suPAR is involved in a variety of cellular processes including proteolysis, migration, proliferation, and adhesion through its interactions with ECM proteins such as integrins and vitronectins as well as other receptors. Also, suPAR is a regulator of the plasminogen activation system since it can scavenge and bind the serine protease uPA in the ECM thereby competitively inhibiting uPAR. Cleaved suPAR interacts with FPRL-1 to induce chemotaxis of immune cells (e.g., monocytes, neutrophils). suPAR D1 is rapidly cleared from circulation and is biologically inactive. suPAR is released into circulation during infection, and therefore, the circulating concentrations of suPAR reflect the extent of immune activation and inflammation in an individual. Under normal physiological conditions, low levels of circulating suPAR are detected in the healthy population. (B) During P. falciparum infection, PEs bind to and sequester in microvascular endothelial cells. Recognition and binding of parasite products (e.g., PfGPI) to Toll-like receptors on monocytes and ECs activates them to produce and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α) and chemokines, and there is upregulation of the expression of cell-adhesion molecules on endothelial cells (e.g., ICAM-1) to which PEs bind. Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and immune activation stimulate uPAR-expressing cells (e.g., monocytes) to produce and secrete suPAR. Initially, increased local levels of suPAR in children with malaria may promote protective innate immune responses in the host defense by promoting the recruitment of immune cells (e.g., neutrophils and monocytes) to acute sites of infection via its chemotactic effector functions. Through its interactions with other ECM proteins and receptors (e.g., integrins), suPAR can also trigger downstream signaling resulting in the upregulation and expression of adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1). In the absence of early treatment, parasite numbers continue to increase and PEs further accumulate and sequester in microvascular ECs due to the upregulated expression of adhesion molecules. As a result, the production and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines are exacerbated, ultimately resulting in a systemic increase in inflammation and immune activation. Elevated circulating suPAR may amplify the release of cytokines/chemokines and the recruitment of immune cells, which contributes to sustained systemic inflammation and immune activation. Excessive inflammation in malaria could also trigger biological processes leading to marked increases in circulating suPAR. Although further studies are needed to elucidate its role, suPAR may contribute to enhanced chemokine and cytokine secretion that culminates in endothelial dysfunction, multiorgan failure, and death in children with malaria. High circulating concentrations of suPAR in children with malaria may therefore reflect excessive activation of immune cells, adhesion of PEs at sites of inflammation, disturbances in hemostasis, or a combination of these. Collectively, suPAR may be involved in a positive feedback loop that results in high levels of local and systemic immune activation and inflammation through its own pro-inflammatory properties and by activating and recruiting other chemokines and cytokines via chemotaxis. Also, the pathobiology of severe falciparum malaria is associated with upregulation of coagulation pathways. Elevated suPAR levels may indirectly exert pro-coagulant effects by enhanced binding to uPA and competitive inhibition of membrane-bound uPAR thereby indirectly inhibiting uPA-dependent fibrinolysis or by stimulating activation of coagulation mechanisms via intrinsic and extrinsic pathways. Elevated levels of suPAR in children with malaria may reflect the degree to which some or all of these processes occur. EC, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; P. falciparum, Plasmodium falciparum; PfGPI, GPI, Plasmodium falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositol; GPI, glycosylphosphatidylinositol; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; PE, parasitized erythrocyte; SM, severe malaria; suPAR, soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor; uPA, urokinase or urokinase-type plasminogen activator; uPAR, urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor.