Abstract

Distinct cellular DNA damage repair pathways have evolved to maintain the structural integrity of DNA and protect it from the mutagenic effects of genotoxic exposures and processes. However, in the context of modern changes to the human environment and diet, there is a burden of DNA damage products without an evolutionarily dedicated cellular defense mechanism. The occurrence of O6-carboxymethylguanine (O6-CMG) has been linked to meat consumption and hypothesized to contribute to the development of colorectal cancer. However, the cellular fate of O6-CMG is poorly characterized and there is data contradictory data in the literature as to how repair pathways may protect cells from O6-CMG mutagenicity. To better address how cells detect and remove O6-CMG, we evaluated the role of two DNA repair pathways in counteracting the accumulation and toxic effects of O6-CMG. We found that cells deficient in either the direct repair protein O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT), or key components of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway, accumulate higher levels O6-CMG DNA adducts than wild type cells. Furthermore, repair-deficient cells were more sensitive to carboxymethylating agents and displayed an increased mutation rate. These findings suggest that a combination of direct repair and NER circumvent the effects O6-CMG DNA damage.

Keywords: O6-carboxymethylguanine, azaserine, mutagenesis, DNA repair, nucleotide excision repair, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

1. Introduction

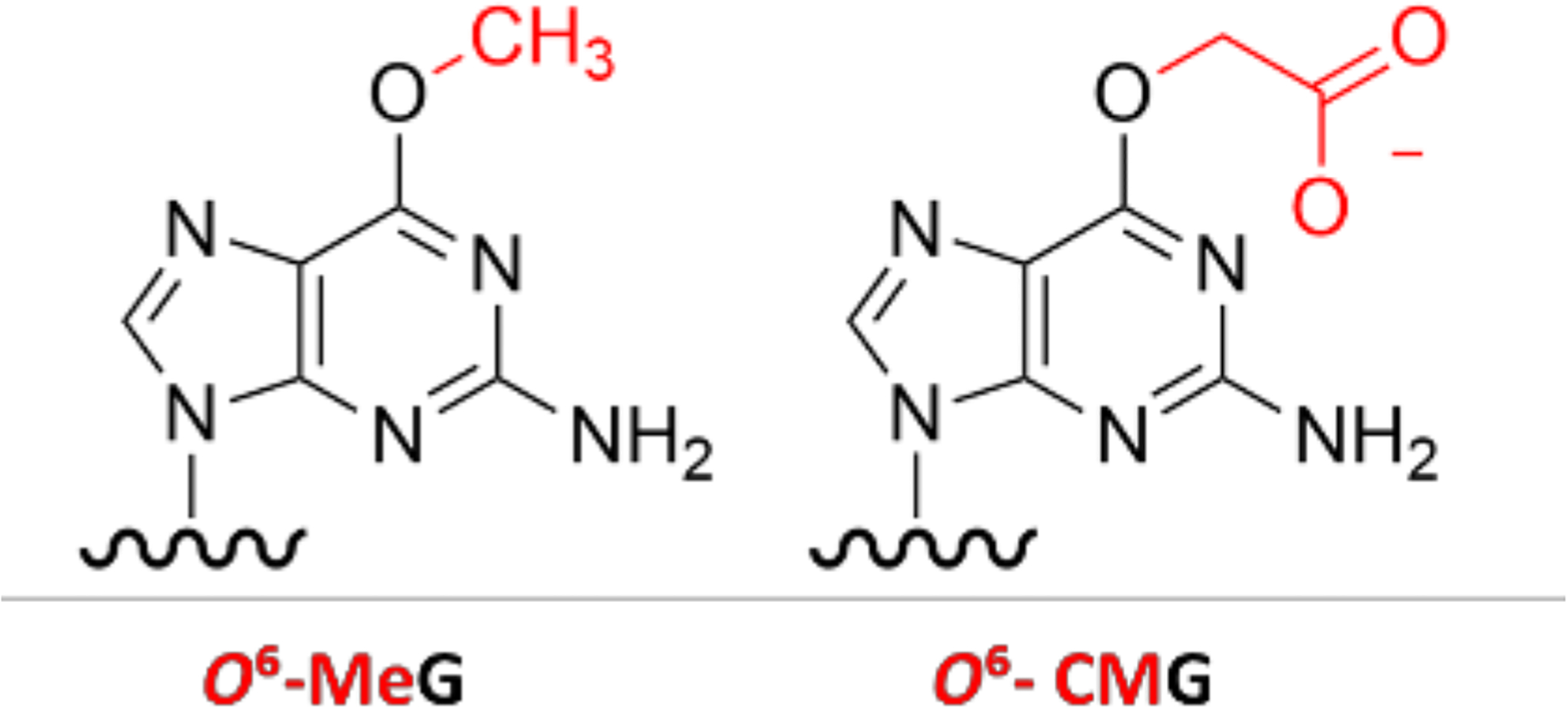

Genomic DNA is continuously damaged during endogenous cellular processes and from exposure to exogenous chemicals. A complex network of proteins has evolved to sense and repair the damage.[1, 2] O6-alkyl-guanine DNA adducts (O6-alkylG) arise from various endogenous and exogenous alkylating agents, and can give rise to mutations that can initiate carcinogenesis.[3–7] For example, O6-methyl-guanine (O6-MeG, Fig. 1) is formed at levels as high as ca. 3,000 adducts per cell per day and causes G to A mutations,[8, 9] and S-Adenosylmethionine has been hypothesized to be an endogenous source of DNA methylation.[10–12] The highly conserved direct reversion repair enzyme MGMT (alkyl guanine transferase, AGT) efficiently removes the methyl group from O6-MeG in DNA by transferring it to a cysteine residue in the protein releasing the original DNA base.[13, 14] Mice deficient in MGMT are hypersensitive to methylating agents and show increased tumorigenesis.[15–18] While MGMT probably evolved to counter O6-MeG adducts, modern changes in exposures related to the environment, diet and medicines, has resulted in the occurrence of additional O6-alkylguanine adducts with more complex structures.[19–22] The involvement of direct reversion in resolving such modifications can have a profound influence on mutation frequency[23, 24] or give rise to drug resistance.[25–27]

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of O6-MeG and O6-CMG adducts

O6-carboxymethylguanine (O6-CMG, Fig. 1) is present at elevated levels in human colon cells in association with high meat consumption. Consequently, it has been hypothesized to contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis associated with a high meat diet.[19, 28, 29] In a first study addressing the role of MGMT in the repair of O6-CMG, the bacterial homolog of MGMT did not remove a radioactively labelled carboxymethyl group from O6-CMG-containing oligonucleotides.[30] By contrast, in a study using purified human proteins, MGMT readily repaired O6-CMG, albeit with lower efficiency than O6-MeG.[31] Other data suggested that structural deviations from O6-MeG:C may reduce substrate binding and repair by alkyltransferase.[14, 32] Finally, recent data from a study in human colon epithelial cells showed that MGMT can remove O6-CMG but with lower efficiency than O6-MeG.[33] In this work, O6-CMG accumulation was dependent on MGMT proficiency, but not cell viability or DNA strand break formation, suggesting that MGMT has a role in the repair of O6-CMG, but the induced cellular phenotypes remain uncharacterized.

In earlier work, MGMT deficiency in lymphoma cells did not influence cell survival upon exposure to the carboxymethylating agent azaserine, but cells deficient in NER were hypersensitive to its toxic effects.[34] While MGMT mediates direct adduct reversion by a single protein, NER involves the concerted action of a minimum of six protein factors (XPC-RAD23B, TFIIH, XPA, RPA and the two endonucleases ERCC1-XPF and XPG), which recognize the lesion and excise it as part of an oligonucleotide.[2] Cells deficient in the XPC, XPA or the TFIIH subunit XPD were particularly sensitive to azaserine-induced cytotoxicity, suggesting NER may target azaserine-induced damage.[34] Furthermore, repair studies in bacteria and yeast suggested that bulky O6-alkylG adducts, including O6-CMG, are repaired by NER. Moreover, these organisms have additional alkyltransferase-like proteins (ATL) that lack the active site cysteine found in MGMT and bind bulkier O6-alkylG adducts and y, by mechanisms not well understood, facilitate repair by NER.[35–39] Since no ATL homologs have been identified in mammals to date, it is unclear whether a similar pathway exists in higher eukaryotes.

To address the individual and combined roles of MGMT and NER in counteracting the mutagenic and cytotoxic effects of O6-CMG, we characterized azaserine cytotoxicity and mutagenicity in repair-deficient cells and quantified corresponding levels of O6-CMG. Our studies show that both direct repair and NER counteract the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of O6-CMG.

2. Results

2.1. Inhibition of human MGMT enhances azaserine mutagenicity and O6-CMG levels in cells.

To clarify the functional relevance of MGMT in repairing carboxymethylated DNA in cells, we tested the role of MGMT in counteracting O6-CMG accumulation and cellular phenotypes induced by exposure to the carboxymethylating agent azaserine. To characterize DNA mutations induced by azaserine, we measured mutagenicity in V79-4 hamster cells using standardhypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT)f assays.[40–43] MGMT was chemically depleted from the V79-4 cells by preconditioning with O6-benzyguanine (O6-BnG), a well-established MGMT suicide inhibitor. The O6-BnG concentration used for the experiment (60 μM) was confirmed to be low enough to avoid any impact on cell viability (Fig. S1)[44, 45] while depleting the cells of active MGMT (Fig. S2). This treatment significantly increased the levels of O6-MeG following exposure to the methylating agent MNNG (Fig. S3).[46] Thus, after treatment with O6-BnG, cells were exposed to azaserine for 24 h and then allowed to grow for one week in drug-free media. To select mutants and allow the growth of mutant colonies only, cells were grown for one additional week in media containing 6-thioguanine to select for cells with mutations in the HPRT gene. Surviving colonies of cells were counted to compare mutagenicity resulting from the treatments.

Azaserine was mutagenic in V79-4 cells and the number of mutant colonies increased with increasing concentrations of azaserine (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, MGMT depletion led to an increase in azaserine-induced mutations (Fig. 2A; dark and light grey vs. black bars). Finally, as negative control, we confirmed that O6-BnG alone was not mutagenic at the concentrations tested (Fig. 2A). The mutagen ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS) was used as a positive control for the mutagenicity assay. Additionally, exposure to increasing levels of azaserine (5 μM) resulted in an increased reduction in cell viability in the presence of O6-BnG (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that lack of MGMT leads to a persistence of DNA adduct mutagenicity and cytotoxicity of azaserine.

Figure 2. Influence of MGMT function on cellular responses to azaserine.

(A) Mutagenicity in V79-4 cells exposed to azaserine as a function of MGMT activity. Mutant colonies were counted manually after two weeks. (B) Level of O6-CMdG after MGMT inhibition and exposure to azaserine. Experiments were performed three times and mean values are represented, with error bars indicating SEM. (C) Viability of V79-4 cells pre-conditioned for 2 h with O6-BnG and exposed to azaserine for 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicates, each with three technical replicates and error bars indicate standard deviation. (A-C) All data were represented using GraphPad Prism 9 (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001). Cell viability data were fit in a nonlinear regression curve, using a dose-response function. Two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test was performed to estimate statistical significance of adducts and mutations. Significance is relative to unexposed control for each set of data.

On the basis of the profile of DNA adducts induced by azaserine,[47] we hypothesized that the influence of MGMT on mutagenicity resulted from increased levels of O6-CMG adducts. Thus, we measured O6-CMG adduct levels in cells exposed to azaserine with or without O6-BnG preconditioning using mass spectrometry. MGMT-proficient cells (Fig. 2B black bars) exposed to azaserine (2 μM) had about 2 O6-CMdG adducts per 107 nucleotides, whereas treatment with O6-BnG resulted in a 23-fold increase of O6-CMdG adducts. Although azaserine can induce both O6-MeG and O6-CMG, it was previously reported that O6-MeG is formed at 10- or 20-fold lower levels than O6-CMG.[33, 47] Nevertheless, we also confirmed that O6-MeG was formed at a much lower level, below the level of quantification (LOQ) for our method, suggesting that the observed mutagenicity is mostly a result of O6-CMG. These data are consistent with O6-CMG adduct accumulation, and a diminished influence of MGMT, contributing to azaserine-induced mutagenicity.

2.2. NER-deficiency enhances mutagenicity and toxicity of azaserine.

To understand the potential relative contributions of NER and MGMT to O6-CMG removal, we characterized the impact of NER factors on azaserine-induced mutagenicity, O6-CMG adduct levels and cytotoxicity. To test the capacity of NER factors to alleviate azaserine-induced mutagenicity, HPRT assays were performed in CHO UV20 cells mutant in ERCC1, a component of the ERCC1-XPF endonuclease. Azaserine was mutagenic at concentrations of 2 μM, the highest dose tested that did not affect cell viability (Fig. 3A dark grey bar). This same dose was not mutagenic in CHO UV20 cells expressing wild type human ERCC1 (Fig. 3A, black bar vs. dark grey bar). Measurements of O6-CMG adduct levels suggested a trend to higher adduct levels in NER-deficient cells compared to complemented cells. However, a high background and signal variability precluded a quantitative determination of the adduct levels in NER proficient and deficient cells. Overall, the data suggest that the NER pathway offers cells protection from the mutagenic effects of azaserine, and that this influence may be due to removal of O6-CMG.

Figure 3. Cellular response to azaserine as a function of NER deficiency, and of NER deficiency in combination with MGMT inhibition.

(A) Mutagenicity in CHO cells cells pre-conditioned with O6-BnG (MGMT −) or not (MGMT +) and exposed to azaserine for 24 h. (B) Cell viability of CHO UV20 + ERCC1 WT and CHO UV20 cells, (C-D) pre-conditioned O6-BnG and treated for 24 h with azaserine. Cell viability data were fit in a nonlinear regression curve, using a dose-response function. Experiments were performed in triplicates, each with three technical replicates and error bars indicate standard deviation. (A-D) All data were represented using GraphPad Prism 9. Statistical significance was calculated by performing two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001).

To test how the repair of O6-CMG by NER impacts cellular sensitivity to azaserine, we exposed the ERCC1-mutant or complemented CHO cells to azaserine (0–10 μM) for 24 h. Cell viability was measured after 2 days of incubation in drug-free media using CellTiter-Glo assays. EC50 values for azaserine toxicity were determined to be 1.7 μM vs 5.7 μM in NER-deficient vs. proficient cells, respectively, corresponding to a 3.5-fold increase in drug resistance conferred by NER (Fig. 3B). These results show that NER-deficient cells were more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of azaserine.

2.3. Combined NER deficiency and MGMT inhibition enhances azaserine-induced mutations.

Considering our finding that both MGMT and NER mitigate azaserine-induced effects, we were interested in understanding the impact of combined NER deficiency and MGMT inhibition. To assess the combined impact on mutagenicity, we pre-conditioned NER-proficient or deficient CHO cells with O6-BnG (20 μM) to deplete MGMT before exposing them to azaserine (0, 0.75, 2 μM) for 24 h. The increase in mutations by MGMT inhibition was significantly higher in NER-deficient vs. proficient cells (Fig. 3A). In the absence of O6-BnG, the mutation rate in NER-deficient cells was 3-fold higher than in NER-proficient cells (Fig. 3A, 2 μM azaserine, black vs. dark grey bars), with O6-BnG, mutant colonies increased by almost 10-fold (Fig. 3A, light grey vs. white bars). We performed studies to determine O6-CMdG adduct levels in this system by the same approach established with the V79 cells, however, exposing CHO cells to 0.75 or 2 μM azaserine led to adduct levels with a high variance in values, with some below quantification limits, so no statistically meaningful comparisons could be made. Nonetheless, the mutagenicity data suggest a potential synergy in the protective roles of MGMT and NER.

To test whether the combined activities of NER and MGMT have a protective effect on azaserine cytotoxicty, we measured cell viability in NER-proficient and deficient CHO cells exposed to azaserine in the presence or absence of O6-BnG. Analogous to the observations in the mutagenicity assays, NER-proficient cells were more sensitive to azaserine when MGMT was inhibited (Fig. 3C). These results were similar to what was observed for V79-4 (Fig. 2C) as well as human colon epithelial cells (Fig. S1). However, the viability of NER-deficient cells was not further reduced by MGMT depletion (Fig. 3D), suggesting that in contrast to adduct levels and mutagenicity, cell death induced by azaserine was not enhanced by co-depletion of NER and direct repair.

2.4. O6-CMG DNA adducts are bound by XPC-RAD23B, but not excised by NER in vitro

We then directly tested the ability of the NER machinery to recognize and excise O6-CMG. The XPC-RAD23B protein is the damage recognition factor in global genome NER. We tested the binding of XPC-RAD23B binds to O6-CMG DNA using EMSA experiments with a synthetic 24mer oligonucleotide with a centrally located O6-CMG adduct.[48] The oligonucleotide was annealed to a fluorescently labelled complementary strand, and the complex was combined with XPC-RAD23B at increasing concentrations. The binding efficiency was assessed by resolving the complexes on a native polyacrylamide gel and visualising free and the slower-migrating XPC-RAD23B-bound DNA band by fluorescence imaging (Fig. 4A). As controls for specific and non-specific binding, we used undamaged (G) and dG-acetylaminofluorene (AAF) containing DNA, respectively. AAF is a well-characterized NER substrate that activates NER by strong XPC-RAD23B binding.[48, 49] By quantifying the ratio of the bands corresponding to free vs. bound duplexes, we found that the O6-CMG-containing duplex bound to XPC-RAD23B with intermediate binding affinity (Kd = 46nM) relative to undamaged (Kd = 81nM) and dG-AAF containing duplex (Kd = 33 nM) (Fig. 4B). Consistent with earlier findings,[48] the difference in specific vs. non-specific binding by XPC-RAD23B is minor (2–3 fold) under these conditions.

Figure 4. O6-CMG binds specifically to XPC-RAD23B but is not excised by NER in vitro.

(A) EMSA of XPC-RAD23B bound to O6-CMG-containing DNA: XPC-RAD23B (0–120 nM) was incubated with Cy-5-labeled duplex DNA containing a central G, O6-CMG or G-AAF residue. Reactions were analyzed by native PAGE and imaged using a Phosphorimager. (B) Quantification of EMSA: binding curve derived from the data in (A). Dissociation constraints (Kd) were calculated from a non-linear fit using the Hill slode on GraphPad Prism 9 (C) In vitro NER assay: G-AAF- (lanes 1–2) and O6-CMG- (lanes 3–4) containing plasmids were incubated with HeLa extract and excision products were detected by annealing to a complementary oligonucleotide with a 5′-4G overhang, which served as a template for end-labelling with [α-32P]-dCTP. The reaction products were resolved on a 14% polyacrylamide gel and imaged using a Phosphorimager.

Having established that XPC-RAD23B specifically binds to O6-CMG, we tested the efficiency of the NER excision reaction on an O6-CMG-containing substrate. We incorporated O6-CMG site-specifically into a plasmid in the same sequence context as used for the XPC-RAD23B binding studies and incubated it with an NER-competent HeLa cell extracts. Dual incision activity was assessed by detecting the NER excision product after annealing to a complementary oligonucleotide and end-labelling with [α-32P]-dATP.[48, 49] A plasmid containing dG-AAF was used as the positive control substrate.[48] Incubation of plasmids with HeLa cell-free extract yielded the expected robust signal for the dG-AAF substrate (Fig 4C, lanes 1,2). Unexpectedly considering the specific binding to XPC-RAD23B, we were unable to detect any excision of O6-CMG-containing DNA (Fig. 4C, lanes 3–4). Thus, while XPC-RAD23B was able to specifically recognize O6-CMG, we were unable to detect NER incision activity, at least under the conditions tested in our experiments.

3. Discussion and Conclusions

Understanding the relationship of disease risk with chemical exposure to genotoxins critically depends on accounting for how cells mitigate adverse effects of DNA damage. Here, we investigated the individual and combined roles of MGMT and NER to clear cellular genomes of O6-CMG. The carboxymethylating agent azaserine was more toxic and mutagenic in cells depleted of MGMT activity or deficient in NER proteins. Additionally, exposure to azaserine in repair-defective cells resulted in a higher number of O6-CMG adducts, consistent with a model that accumulation of DNA adducts causes genomic DNA mutations.

We found that cells deficient in MGMT or NER were hypersensitive to azaserine and accumulated O6-CMG, implying that both MGMT and NER counteract mutagenic effects in cells. These observations are consistent with the general assertion that NER and MGMT cooperate in the repair of other O6-alkylG DNA adducts in human cells.[50, 51] MGMT and NER were suggested to be both involved in the repair of other O6-alkylG adducts, with MGMT being more proficient at transferring small alkyl groups (methyl, ethyl), and NER proteins targeting bulkier O6-alkyG adducts (n-propanol, n-butanol). While MGMT and NER activity seemed specialized and complementary with regards to the adduct structure, both pathways were active to some extent in the repair of all tested adducts; in particular, their activity was similar for adducts of intermediate size (i-propanol, i-butanol). [50] Indeed, various adducts have been shown to be repaired by a combination of repair pathways.[52–55] This observation and the findings of the present work suggest that while repair pathways specialized over evolution to target several types of DNA damage, adducts with complex chemical structures can activate multiple networks of factors and are better handled by a combination or cooperation of repair machineries.

We found that the NER damage sensor protein XPC-RAD23B bound O6-CMG with a specificity typical of a lesion that is repaired with intermediate efficiency,[48] but we did not observe the excision of an O6-CMG-containing oligonucleotide. This result was unexpected considering the clear effect of NER on O6-CMG adduct levels and mutagenesis. The lack of repair may be explained by a discrepancy of conditions for in vitro and cellular assays, although for most substrates there seems to be a good correlation between repair efficiency in the two systems. Following damage recognition by the XPC-RAD23B protein, which is selective for the thermodynamic destabilization of a DNA duplex, the XPD helicase is thought to verify the presence of a chemical alteration in DNA.[56] It is conceivable that O6-CMG does not fulfil structural requirements for verification by XPD, based on its size or conformation, at least under our conditions.

Another possible explanation is that NER-triggering adducts larger than O6-CMG may be formed by azaserine in cells and are missing in our biochemical experiments. For example, it has been recently suggested an azaserine-G DNA adduct maybe formed initially that yields O6-CMG by hydrolysis of the serine moiety on DNA rather than prior to reaction with DNA.[57] If this larger adduct, which was so far only characterized from a chemical reaction, but not in cells, is relevant to O6-CMG formation in cells, it may then be a key to triggering NER. Higher O6-CMG levels in the absence of NER may therefore be explained by a failure to repair azaserine-G as an intermediate in O6-CMG formation.

A third and most intriguing possibility is that NER of O6-CMG needs an additional component that is not present in our cell extract. Previous work in yeast and bacteria has revealed the existence of alkyltransferase-like (ATL) proteins, homologs of MGMT but lack of transferase activity due to a mutation in the active site cysteine residue.[36, 37, 58, 59] It has been shown how that ATL proteins serve as recognition and accessory factors for bulky O6-alkylG in the NER pathway. ATLs bind to O6-alkylGs and can channel them into being repaired by NER. Although ATL homologs have not been yet identified in higher eukaryotes, it is conceivable that either hitherto unknown ATL proteins or perhaps even MGMT itself might have a similar role of crosstalk between repair pathways for O6-CMG in higher organisms. The presence of an ATL protein could explain the collaboration between direct repair and NER we observe in cells, even if we do not detect NER activity in vitro.

The results of this study indicate that two DNA repair pathways, NER and MGMT, cooperate to remove O6-CMG adducts in mammalian cells, alleviating mutagenic and cytotoxic consequences. This finding is highly relevant for understanding colon carcinogenesis as it suggests how both MGMT and NER have a protective role towards the toxicity and mutagenicity of O6-CMG, and how their deficiency might increase the risk of mutations and cancer development. Finally, these results suggest a potential cooperation between MGMT and NER in removing O6-CMG, making the identification of gene deficiencies even more compelling to predict cancer susceptibilities. A major open question concerns the mechanism of how NER and MGMT target O6-CMG in a potentially concerted manner and whether other as of yet unidentified factors are involved in the repair of these adducts.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Cell strains and culture conditions

V79-4 ATCC® CCL-93™ cells were purchased from ATCC (Virginia, USA), Lot number 59313378. CHO UV20 (ERCC1-deficient) and CHO UV20 transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing wild-type hERCC1 were generated as described previously.[60] All cells were maintained as monolayers in 10-cm dishes in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C and regularly tested for mycoplasma. Culture media for CHO and V79 cells was DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Culture media for HCEC cells was 80% DMEM and 20% M199 Earle, supplemented with 2% of Hyclone serum, 25 ng/L epidermal growth factor, 1 μg/L hydrocortisone, 10 μg/L insulin, 2 μg/L transferrin, 50μg/L gentamycin, 0.9 ng/L sodium selenite.

4.2. Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (2 × 103 per well for V79-4 cells, 3 × 103 per well for CHO cells, 4 × 103 per well for HCEC cells, 10 × 103 per well for HAP1 cells) and exposed to solutions of test compounds as aqueous solutions with a final concentration of 0.1% of DMSO. Cells were exposed to TritonX (Sigma) as a positive control for inducing cell death, and with 0.1% DMSO as negative control. After 24 h azaserine exposure, cells were washed, and drug-free medium was added. Cell survival was measured 2 or 3 days later on the basis of ATP quantitation with the CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega; Wisconsin, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.[61] Three technical replicates of three biological replicates were performed. Luminescence values obtained for analysis of ATP in drug-treated cells were normalized to those of DMSO-treated cells (assigned to 100% viability). Data were analysed and plotted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.; California, USA).

4.3. Mutagenicity assay

The hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) assay for mutagenicity was performed on V79-4 and CHO cells by an established protocol.[62] Cells were seeded in 30-cm dishes (5 × 105 cells per dish). Pre-existing hprt− mutants were cleansed by incubating cells in medium supplemented with hypoxanthine, aminopterin and thymidine (HAT). After three days, HAT medium was removed and replaced by normal DMEM medium and left for 24h. Cells were reseeded in 10-cm dishes (105 cells per dish) and one 10-cm dish was prepared for each condition to test. Cells were allowed to attach overnight. Cells were pre-conditioned for 2 h with O6-BnG (0 – 60 μM for V79-4, 0 – 20 μM for CHO) followed by exposure to azaserine (0 – 2 μM for V79-4, 0 – 1.25 μM for CHO) for 24 h. DMSO final concentration was 0.06%. Cells for positive control were exposed to 1.7 mM or 3.5 mM ethyl methane sulfonate (EMS). After time of exposure, culture medium was changed with fresh drug-free DMEM medium. Cells were let grow for 7 days, and medium was changed every three days. Per each condition, cells were reseeded in four 10-cm dishes (2 × 105 cells per dish) in selection medium containing 10 μg/ml of 6-thioguanine, and in two 6-cm dishes (300 cells per dish) in normal DMEM medium for plating efficiency (PE) calculations. All cells were incubated for 14 days, and medium was changed every 4 days (for the four selection dishes, fresh medium contained always 6-TG). After 14-days of hprt− mutant selection, cells were stained with 50 % Giemsa staining solution (v/v) in methanol. Clones were counted manually and normalized to the PE in the case of CHO UV20 + ERCC1 WT and KO, for which PE was the most different. Data were analyzed and plotted on GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc.; California, USA). Statistical significances of differences relative to control were calculated using two-way ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001).

4.4. Mass Spectrometric quantitation of O6-MedG and O6-CMdG

O6-MedG and O6-CMdG adduct levels were measured in DNA from cells pre-conditioned with O6-BnG (0 or 60 μM for V79-4; 0 or 20 μM for CHO) for 2 h, followed by a 24 h-exposure with azaserine (0 or 2 μM for both V79-4 and CHO cells). To confirm MGMT-inhibition, O6-MedG adduct levels were measured in cells exposed to MNNG (30 μM for V79-4 and CHO; 10 μM for HCEC) +/− O6-BnG. DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen; Germany) following manufacturer’s instructions[63] and enzymatically hydrolyzed in the presence of isotopically labelled internal standards, D3-O6-MedG and 15N5-O6-CMdG (100 fmol and 200 fmol respectively) as previously reported.[57] Following further sample clean-up by solid phase extraction, samples were analyzed by nanoLC-ESI-hrMS2) following a reported method.[33, 57] PRM scanning in positive ionization mode was performed based on the following transitions for O6-MedG, D3-O6-MedG, O6-CMdG, and 15N5-O6-CMdG: m/z 282.1195 > 166.0722, m/z 285.1384 > 169.0911 and m/z 326.1096 > 210.0622, m/z 331.0946 > 215.0472. MS instrument control and data acquisition were performed with Xcalibur (version 4.0, ThermoFisher Scientific).

4.5. Oligonucleotides

Unmodified oligos (5′-CTATTACCGGCGCCACATGTCAGC-3′ and its sequence-complement 5′-GCTGACATGTGGCGCCGGTAATAG-3′) were purchased from IDT (Iowa, USA). For EMSA assays, the complementary oligonucleotides were labeled with Cy5. O6-CMG 24mer oligonucleotide sequences were 5′-CTATTACCGXCGCCACATGTCAGC-3′, where X = O6-CMG. O6-CMG-modified oligo and AAF-modified (5′-CTATTACCGXCGCCACATGTCAGC-3′, X = AAF) oligo were synthesized by solid-phase DNA synthesis on a Mermade 4 DNA synthesizer (Bioautomation Corporation; Texas, USA) in trityl-on mode on a 1-μmol scale, purified and characterized as previously reported.[49, 64] O6-CMG phosphorimidite was obtained as previously reported.[65] The ssDNA concentration was determined by monitoring UV absorption at 260 nm on a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermofisher; Massachusetts, USA).

4.6. Protein expression and purification

XPC-RAD23 was purified as described previously.[66]

4.7. Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA assay was performed on O6-CMG-modified oligo annealed with Cy5-labeled complementary strands (10 nM) and allowed to react with XPC-RAD23B (0 – 120 nM) in the presence of non-modified 24mer duplex of the same sequence (30 nM), using our previously described conditions.[48] Unmodified DNA was used as a negative control and AAF-modified oligo was used as a positive control. The reaction mixtures (200 fmol oligo) were loaded onto a native 5% polyacrylamide gel pre-equilibrated with 0.5× TBE buffer and run at 4 °C for 1 h at 20 mA. Gels were imaged using a PhosphorImager (Typhoon RGB, GE Healthcare). Band intensities were quantified with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad; California, USA). Dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated with GraphPad Prism 9 using a nonlinear fit and the Hill slope method.

4.8. O6-CMG-single stranded circular DNA production and NER assay

Single stranded circular DNA was generated from p98 (with a NarI site engineered into pBlusscript II SK+) as previously described.[49] The oligonucleotides oligo-O6-CMG-10 and oligo-O6-CMG-12 (100 pmol) were 5’-phosphorylated by incubation with 20 units of T4 PNK and 2 mM ATP at 37 °C for 2 h. After annealing with 30 pmol of single-stranded p98, the mixture was incubated with dNTPs (800 μM), T4 DNA polymerase (90 units), and T4 DNA ligase (200 units) to generate the covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA containing a single O6-CMG adduct. The cccDNA was purified by caesium chloride/ethidium bromide density gradient centrifugation, followed by consecutive butanol extractions to remove the ethidium bromide, and finally concentrated on a Centricon YM-30 (Millipore, Massachusetts, USA). The collected cccDNA was further purified by sucrose gradient centrifugation to remove traces of ethidium bromide and nicked DNA. The in vitro NER assay was performed using HeLa cell extract (2 μL of 21 mg/mL) as previously described. [48, 49] The reaction products were visualized using a PhosphorImager (Typhoon RGB, GE Healthcare).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank Xuan Li (ETH Zurich) for preliminary testing of HPRT assay, and Jiyoung Park (IBS Korea) for support with cell culture. We thank Miaw-Sheue Tsai, Aye Chin Twin and Judy Lin (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) for help with XPC-RAD23B expression and Nathalie Ziegler (ETH Zurich) for her valuable insights on mass spectrometry data. Work in the ODS laboratory was supported by the Korean Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R022-A1) and the National Cancer Institute (P01-CA092584). Work in the SJS laboratory was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (156280) and the European Research Council (260341). CMNA acknowledges support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (201902).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Giglia-Mari G, Zotter A, and Vermeulen W, DNA damage response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2011. 3(1): p. a000745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clauson C, Schärer OD, and Niedernhofer L, Advances in Understanding the Complex Mechanisms of DNA Interstrand Cross-Link Repair. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 2013. 5(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tubbs A and Nussenzweig A, Endogenous DNA Damage as a Source of Genomic Instability in Cancer. Cell, 2017. 168(4): p. 644–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montesano R, Alkylation of DNA and tissue specificity in nitrosamine carcinogenesis. J Supramol Struct Cell Biochem, 1981. 17(3): p. 259–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hemeryck LY, et al. , In vitro DNA adduct profiling to mechanistically link red meat consumption to colon cancer promotion. Toxicol Res (Camb), 2016. 5(5): p. 1346–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemeryck LY, et al. , DNA adduct profiling of in vitro colonic meat digests to map red vs. white meat genotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol, 2018. 115: p. 73–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsao N, Schärer OD, and Mosammaparast N, The complexity and regulation of repair of alkylation damage to nucleic acids. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2021. 56(2): p. 125–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tice RRS, R.B., DNA repair and replication in aging organisms and cells. Handbook of the Biology of Aging., 1985: p. 173–224. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu D, Calvo JA, and Samson LD, Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat Rev Cancer, 2012. 12(2): p. 104–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margison GP, et al. , Variability and regulation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Carcinogenesis, 2003. 24(4): p. 625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrows LR and Magee PN, Nonenzymatic methylation of DNA by S-adenosylmethionine in vitro. Carcinogenesis, 1982. 3(3): p. 349–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rydberg B and Lindahl T, Nonenzymatic methylation of DNA by the intracellular methyl group donor S-adenosyl-L-methionine is a potentially mutagenic reaction. Embo j, 1982. 1(2): p. 211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pegg AE, Dolan ME, and Moschel RC, Structure, Function, and Inhibition of O6-Alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase, in Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology, Cohn WE and Moldave K, Editors. 1995, Academic Press. p. 167–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKeague M, et al. , The Base Pairing Partner Modulates Alkylguanine Alkyltransferase. ACS Chemical Biology, 2018. 13(9): p. 2534–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuzuki T, et al. , Targeted disruption of the DNA repair methyltransferase gene renders mice hypersensitive to alkylating agent. Carcinogenesis, 1996. 17(6): p. 1215–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwakuma T, et al. , High incidence of nitrosamine-induced tumorigenesis in mice lacking DNA repair methyltransferase. Carcinogenesis, 1997. 18(8): p. 1631–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakumi K, et al. , Methylnitrosourea-induced tumorigenesis in MGMT gene knockout mice. Cancer Res, 1997. 57(12): p. 2415–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shiraishi A, Sakumi K, and Sekiguchi M, Increased susceptibility to chemotherapeutic alkylating agents of mice deficient in DNA repair methyltransferase. Carcinogenesis, 2000. 21(10): p. 1879–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aloisi CMN, Sandell ES, and Sturla SJ, A Chemical Link between Meat Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Development? Chem Res Toxicol, 2021. 34(1): p. 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu J, Christison T, and Rohrer J, Determination of dimethylamine and nitrite in pharmaceuticals by ion chromatography to assess the likelihood of nitrosamine formation. Heliyon, 2021. 7(2): p. e06179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erskine D and Wood D, What is the significance of nitrosamine contamination in medicines? Drug Ther Bull, 2021. 59(3): p. 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spratt TE and Campbell CR, Synthesis of oligodeoxynucleotides containing analogs of O6-methylguanine and reaction with O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Biochemistry, 1994. 33(37): p. 11364–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerson SL, MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nature Reviews Cancer, 2004. 4(4): p. 296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabharwal A and Middleton MR, Exploiting the role of O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyltransferase (MGMT) in cancer therapy. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2006. 6(4): p. 355–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Nifterik KA, et al. , Absence of the MGMT protein as well as methylation of the MGMT promoter predict the sensitivity for temozolomide. Br J Cancer, 2010. 103(1): p. 29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bobola MS, et al. , O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity is associated with response to alkylating agent therapy and with MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma and anaplastic glioma. BBA Clin, 2015. 3: p. 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitange GJ, et al. , Induction of MGMT expression is associated with temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma xenografts. Neuro Oncol, 2009. 11(3): p. 281–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin MH, et al. , Red meat enhances the colonic formation of the DNA adduct O6-carboxymethyl guanine: implications for colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Res, 2006. 66(3): p. 1859–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanden Bussche J, et al. , O6-carboxymethylguanine DNA adduct formation and lipid peroxidation upon in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of haem-rich meat. Mol Nutr Food Res, 2014. 58(9): p. 1883–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shuker DE and Margison GP, Nitrosated glycine derivatives as a potential source of O6-methylguanine in DNA. Cancer Res, 1997. 57(3): p. 366–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senthong P, et al. , The nitrosated bile acid DNA lesion O6-carboxymethylguanine is a substrate for the human DNA repair protein O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013. 41(5): p. 3047–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zang H, et al. , Kinetic analysis of steps in the repair of damaged DNA by human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(35): p. 30873–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kostka T, et al. , Repair of O6-carboxymethylguanine adducts by O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in human colon epithelial cells. Carcinogenesis, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Driscoll M, et al. , The cytotoxicity of DNA carboxymethylation and methylation by the model carboxymethylating agent azaserine in human cells. Carcinogenesis, 1999. 20(9): p. 1855–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazon G, et al. , The alkyltransferase-like ybaZ gene product enhances nucleotide excision repair of O(6)-alkylguanine adducts in E. coli. DNA Repair (Amst), 2009. 8(6): p. 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson OJ, et al. , Alkyltransferase-like protein (Atl1) distinguishes alkylated guanines for DNA repair using cation-pi interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(46): p. 18755–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latypov VF, et al. , Atl1 regulates choice between global genome and transcription-coupled repair of O6-alkylguanines. Mol Cell, 2012. 47(1): p. 50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aramini JM, et al. , Structural basis of O6-alkylguanine recognition by a bacterial alkyltransferase-like DNA repair protein. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(18): p. 13736–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubitschek HE and Sepanski RJ, Azaserine: survival and mutation in Escherichia coli. Mutat Res, 1982. 94(1): p. 31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nestmann ER, et al. , Recommended protocols based on a survey of current practice in genotoxicity testing laboratories: II. Mutation in Chinese hamster ovary, V79 Chinese hamster lung and L5178Y mouse lymphoma cells. Mutat Res, 1991. 246(2): p. 255–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schweikl H and Schmalz G, Glutaraldehyde-containing dentin bonding agents are mutagens in mammalian cells in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res, 1997. 36(3): p. 284–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schweikl H, Schmalz G, and Rackebrandt K, The mutagenic activity of unpolymerized resin monomers in Salmonella typhimurium and V79 cells. Mutat Res, 1998. 415(1–2): p. 119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Follmann W and Lucas S, Effects of the mycotoxin ochratoxin A in a bacterial and a mammalian in vitro mutagenicity test system. Arch Toxicol, 2003. 77(5): p. 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dolan ME and Pegg AE, O6-benzylguanine and its role in chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res, 1997. 3(6): p. 837–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Konduri SD, et al. , Blockade of MGMT expression by O6 benzyl guanine leads to inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth and induction of apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res, 2009. 15(19): p. 6087–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdel-Fattah R, et al. , Methylation of the O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase promoter suppresses expression in mouse skin tumors and varies with the tumor induction protocol. Int J Cancer, 2006. 118(3): p. 527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu Y, et al. , Quantification of Azaserine-Induced Carboxymethylated and Methylated DNA Lesions in Cells by Nanoflow Liquid Chromatography-Nanoelectrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry Coupled with the Stable Isotope-Dilution Method. Anal Chem, 2016. 88(16): p. 8036–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yeo JE, et al. , The efficiencies of damage recognition and excision correlate with duplex destabilization induced by acetylaminofluorene adducts in human nucleotide excision repair. Chem Res Toxicol, 2012. 25(11): p. 2462–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gillet LC, Alzeer J, and Scharer OD, Site-specific incorporation of N-(deoxyguanosin-8-yl)-2-acetylaminofluorene (dG-AAF) into oligonucleotides using modified ‘ultra-mild’ DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res, 2005. 33(6): p. 1961–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du H, et al. , Repair and translesion synthesis of O (6)-alkylguanine DNA lesions in human cells. J Biol Chem, 2019. 294(29): p. 11144–11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bronstein SM, Skopek TR, and Swenberg JA, Efficient repair of O6-ethylguanine, but not O4-ethylthymine or O2-ethylthymine, is dependent upon O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and nucleotide excision repair activities in human cells. Cancer Res, 1992. 52(7): p. 2008–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaim IA, et al. , A novel role for transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair for the in vivo repair of 3,N4-ethenocytosine. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(6): p. 3242–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu D and Samson LD, Direct repair of 3,N(4)-ethenocytosine by the human ALKBH2 dioxygenase is blocked by the AAG/MPG glycosylase. DNA Repair (Amst), 2012. 11(1): p. 46–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jurado J, et al. , Role of mismatch-specific uracil-DNA glycosylase in repair of 3,N4-ethenocytosine in vivo. DNA Repair (Amst), 2004. 3(12): p. 1579–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartwig A, The role of DNA repair in benzene-induced carcinogenesis. Chem Biol Interact, 2010. 184(1–2): p. 269–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsutakawa SE, et al. , Envisioning how the prototypic molecular machine TFIIH functions in transcription initiation and DNA repair. DNA Repair, 2020. 96: p. 102972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geisen SM, et al. , Direct Alkylation of Deoxyguanosine by Azaserine Leads to O(6)-Carboxymethyldeoxyguanosine. Chem Res Toxicol, 2021. 34(6): p. 1518–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tubbs JL, et al. , Flipping of alkylated DNA damage bridges base and nucleotide excision repair. Nature, 2009. 459(7248): p. 808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomaszowski KH, et al. , The bacterial alkyltransferase-like (eATL) protein protects mammalian cells against methylating agent-induced toxicity. DNA Repair (Amst), 2015. 28: p. 14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Orelli B, et al. , The XPA-binding domain of ERCC1 is required for nucleotide excision repair but not other DNA repair pathways. J. Biol. Chem, 2010. 285(6): p. 3705–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orelli B, et al. , The XPA-binding domain of ERCC1 is required for nucleotide excision repair but not other DNA repair pathways. J Biol Chem, 2010. 285(6): p. 3705–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein CB, Broday L, and Costa M, Mutagenesis assays in mammalian cells. Curr Protoc Toxicol, 2001. Chapter 3: p. Unit3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gong J and Sturla SJ, A synthetic nucleoside probe that discerns a DNA adduct from unmodified DNA. J Am Chem Soc, 2007. 129(16): p. 4882–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aloisi CMN, et al. , Sequence-Specific Quantitation of Mutagenic DNA Damage via Polymerase Amplification with an Artificial Nucleotide. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2020. 142(15): p. 6962–6969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raz MH, et al. , High Sensitivity of Human Translesion DNA Synthesis Polymerase kappa to Variation in O(6)-Carboxymethylguanine Structures. ACS Chem Biol, 2019. 14(2): p. 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheon NY, et al. , Single-molecule visualization reveals the damage search mechanism for the human NER protein XPC-RAD23B. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019. 47(16): p. 8337–8347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.