Abstract

The Src tyrosine kinase is a strong tumor promotor. Over a century of research has elucidated fundamental mechanisms that drive its oncogenic potential. Src phosphorylates effector proteins to promote hallmarks of tumor progression. For example, Src associates with the Cas focal adhesion adaptor protein to promote anchorage independent cell growth. In addition, Src phosphorylates Cas to induce Pdpn expression in order to promote cell migration. Pdpn is a transmembrane receptor that can independently increase cell migration in the absence of oncogenic Src kinase activity. However, to our knowledge, effects of Src kinase activity on anchorage independent cell growth and migration have not been examined in the absence of Pdpn expression. Here, we analyzed the effects of an inducible Src kinase construct in knockout cells with and without exogenous Pdpn expression on cell morphology migration and anchorage independent growth. We report that Src promoted anchorage independent cell growth in the absence of Pdpn expression. In contrast, Src was not able to promote cell migration in the absence of Pdpn expression. In addition, continued Src kinase activity was required for cells to assume a transformed morphology since cells reverted to a nontransformed morphology upon cessation of Src kinase activity. We also used phosphoproteomic analysis to identify 28 proteins that are phosphorylated in Src transformed cells in a Pdpn dependent manner. Taken together, these data indicate that Src utilizes Pdpn to promote transformed cell growth and motility in complementary, but parallel, as opposed to serial, pathways.

Introduction

The Src tyrosine kinase has been implicated in the establishment and progression of many types of cancer 1–3. On a cellular level, Src phosphorylates tyrosines on effector proteins to promote tumor progression. This process relies on downstream signaling events including gene transcriptional activation. The podoplanin (Pdpn) receptor plays an important role in this oncogenic pathway 4–7. Indeed, along with Src, Pdpn has been identified as a powerful tumor promoter and functionally relevant chemotherapeutic target 8–10.

Src utilizes adaptor proteins including p130Cas/BCAR1 to increase anchorage independent cell growth, motility, and tumor progression 11. However, Src does not need to phosphorylate p130Cas/BCAR1 on its substrate domain to increase nonanchored cell growth. In contrast, Src phosphorylates this adaptor protein on specific tyrosines to induce Pdpn mRNA and protein expression in order to increase tumor cell motility 5,12. In fact, Pdpn expression can account for all of the increased motility conferred by Src transformation 4,5,13.

Model cell systems have been developed to investigate the effects of Src and Pdpn on anchorage independent cell growth and motility. Results from experiments performed on nontransformed homozygous Pdpn knockout cells transfected with control vectors or expression constructs to drive exogenous Pdpn expression indicate that Pdpn expression effectively promotes cell motility but not anchorage independent grow in the absence of oncogenic Src kinase activity. In addition, results from experiments with nontransformed and Src transformed wild type cells indicate that oncogenic Src kinase activity can increase anchorage dependent independent growth and motility in the presence of endogenous Pdpn expression 4,14,15. However, the effects of oncogenic Src kinase activity on cells that do not express Pdpn have not been clearly evaluated. Here, we utilized a temperature sensitive Src kinase construct to evaluate the effects of Src on Pdpn knockout cells transfected with control or Pdpn expression constructs. Results from these experiments indicate that Src requires Pdpn to promote cell motility, but not anchorage independent growth. In addition, phosphopeptide analysis of protein from these cells indicates that Pdpn modulates Src mediated phosphorylation events on Src and other proteins. Moreover, data from this study indicates that consistent Src activity is required to maintain transformed morphology, which can be normalized after Src kinase activity is inhibited.

Methods

Cell transfection and culture

Homozygous null Pdpn knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts transfected with expression vectors to drive constitutive exogenous expression of Pdpn (PdpnWT), Pdpn and vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc), or empty parental pEF4Zeo and pBabePuro vectors (PdpnKO) were used as described 14,15. The coding sequence for temperature sensitive vSrc kinase (tsSrc) 16 was synthesized with flanking EcoR1 and Sal1 restriction enzyme sites (Genscript), inserted into the complimentary sites of pBabeHygro, and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) into PdpnKO or PdpnWT cells to produce cells that express tsSrc with Pdpn (PdpnWTtsSrc) or without Pdpn (PdpnKOtsSrc cells), respectively. This tsSrc construct is active at 34°C (permissive temperature) and inactive at 39°C (nonpermissive temperature) 16. Transfectants were selected with appropriate antibiotic including zeocin (Invivogen, ant-zn-5p), puromycin (Calbiochem, 540411), and/or hygromycin (Invivogen, ant-hg-5) and cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 100% humidity in DMEM (Corning, 10–014-CV) supplemented with 10% FBS (Seradigm, 89510–186) and 25 mM HEPES (VWR, J848–500ML). Media was supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Corning, 30–002-CI) and 1% amphotericin B (Corning, 30–003-CF) for maintenance. Cells were cultured at 34°C or 39°C to analyze effects of active or inactive Src kinase, respectively.

Cell morphology, growth, and motility assays

Cell growth was analyzed as previously described 4,14,15. Cells (20,000/well) were plated in standard 12 well (Corning, 353046) or 24 well low attachment cluster plates (Corning, 3473) and cultured for 20 hours at the nonpermissive temperature (39°C). Cells on standard dishes were then dissociated with 0.25% trypsin (Corning, 25–050-Cl) and counted with a Coulter counter to verify equal plating and viability. Cells on low attachment dishes were then incubated at the nonpermissive (39°C) or permissive (34°C) temperature for an additional 7 days, collected by centrifugation, trypsinized, and counted with a Coulter counter.

Wound healing cell migration assays were performed as described 4,14,15. Briefly, confluent monolayers grown at the nonpermissive temperature (39°C) were scratched, washed with PBS (Cytvia, SH30028.02), and incubated for 18 hours at the permissive (34°C) or nonpermissive (39°C) temperature. The number of cells that migrated into a 200 × 200 µM area at the center of the wound was counted. Cells were visualized with an Echo Revolve brightfield microscope equipped with 10x and 20x objectives and Echo Pro imaging software (version 3.2.0, Discover Echo, Inc. San Diego, California).

Transwell migration assays were performed as described 15. Briefly, cells were plated to achieve 80% confluency (about 800,000 cells/membrane) on 6-well Transwell membrane inserts with 8 μM pores (Corning, 3422) at the permissive temperature (34°C) for 24 hours. Cells on the top and bottom of the membrane were trypsinized separately and counted using a Coulter Counter.

To examine actin fiber morphology, cells were cultured on 35 mm poly-D-lysine glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corp, P35GC-1.5–14-C) at the nonpermissive (39°C) or permissive (34°C) temperature for 72 hours, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100, and then stained with phalloidin-Texas Red (Invitrogen, T7471) and Hoechst (Molecular Probes, 33342) according to manufacturer recommendations. Cells were visualized on a Carl Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63X objective, apotome 2, filter sets to detect RFP (excitation 560±40, emission 630±75) and Hoechst (excitation 390±22, emission 460±50) with a Zeiss AxioCam Mrc camera Rev3 equipped with Zen Pro 2.3 software as previously described 15,17,18.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described 4,14,15. Cells were grown at the nonpermissive temperature (39°C) for 48 hours before cells pellets were collected at indicated timepoints and temperatures. Protein was extracted with lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris HCl, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM PMSF), resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE (20 µg/lane), transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (MilliporeSigma, IPVH00010), and detected by antibodies specific for Pdpn (8.1.1, University of Iowa Developmental Hybridoma Bank), active Src (Cell Signaling, 6494), vSrc (MilliporeSigma, 05–185), HSP90 (Proteintech, 60318–1-Ig), or β-actin (MilliporeSigma, A1978). Primary antibodies were detected by HRP conjugated secondary anti-Syrian hamster (Jackson, 107–035-142), anti-rabbit (Jackson, 711–035-152), or anti-mouse (Jackson, 115–035-003) antibodies, respectively, by chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific, 32106). Equal loading and transfer were confirmed by staining gels with Coomassie blue and membranes with India ink.

Phosphopeptide analysis

Protein from cells incubated for 24 hours at nonpermissive (39°C) or permissive (34°C) temperature was extracted with lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris HCl, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 mM PMSF). For sample preparation, 0.3 mg of protein from each sample was reduced with 20 mM DTT and incubated at 60°C for 30 minutes. After cooling to room temperature, 40 mM iodoacetamide was added and the samples were kept in the dark for 1 hour to block free cysteine. The samples were dialyzed against 50 mM TEAB for 6 hours and digested with Trypsin at 1:50 (w:w, trypsin:sample) for 37°C overnight. The digested peptides were further filtered with Amicon ultra centrifugal filters (10kD MWKO, Merck Millipore, MA), and dried under vacuum. The digested peptides were labeled with Thermo TMTpro (Lot #: WC320807) by manufacture’s protocol, pooled at a 1:1 ratio and fractionated by fractionated by high-pH RPLC chromatography using Agilent 1100 series. The sample was solubilized in 250 µl of 20 mM ammonium (pH10), and separated on an Xbridge column (Waters, C18 3.5 µm 2.1X150 mm) using a linear gradient of 1%B/min from 2–45% of B (buffer A: 20 mM ammonium, pH 10, B: 20 mM ammonium in 90% acetonitrile, pH10), monitored by UV at 214 nm, and collected in 1 minute fractions. A small portion of selected fractions was used for proteome analysis and the rest of all fractions were combined into 6 fractions as described 19 for phosphor-peptide enrichment using a IMAC method adapted from Mertins et al 20.

LC-MSMS was performed using a Dionex rapid-separation liquid chromatography system interfaced with an Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sample was loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap 100 trap column (75 µm x 2 cm, ThermoFisher) and washed with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid for 5 min with a flow rate of 5 µl/min. The trap was brought in-line with the nano analytical column (nanoEase, MZ peptide BEH C18, 130A, 1.7um, 75umx20cm, Waters) with flow rate of 300 nL/min with a multistep gradient (4% to 15% buffer (Buffer A: 0.2% formic acid in water, Buffer B: 0.16% formic acid and 80% acetonitrile] in 20 min, then 15%–25% B in 40 min, followed by 25%–50% B for 30 min). The DDA method was used for analysis of phosphor peptides. The scan sequence began with an MS1 spectrum (Orbitrap analysis, resolution 120,000, scan range from 350–1600 Th). Parent masses were isolated in the quadrupole and fragmented with higher-energy collisional dissociation with a normalized collision energy of 33%. The fragments were scanned in Orbitrap with resolution of 30,000 with scan lower limit set at 110 amu. The top S (3 sec) duty cycle scheme was used for determining numbers of MSMS performed for each cycle. A synchronous precursor selection (SPS) method was used for proteomic samples. After MS1 spectrum was acquired as described above, peptide ions were collected for MSMS by collision-induced dissociation (CID) with collision energy 35 and scanned in the ion trap. Following acquisition of each MS2 spectrum, 10 MS2 fragment ions were captured as MS3 precursors using isolation waveforms with multiple frequency notches in HCD cell and fragmented with higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) with a normalized collision energy set at 55% and scanned in the Orbitrap with scan range 100–500 with resolution of 50,000. Differentially phosphorylated peptides were filtered for values at the permissive temperature being at least 50% higher than the nonpermissive temperature for each cell line with p<0.05 by t-test (n=2). Pdpn dependent events were identified by induction at permissive temperature in PdpnWTtsSrc cells being at least 50% higher than induction is PdpnKOtsSrc cells. Data can be accessed as MassIVE dataset number MSV000088244 at http://massive.ucsd.edu.

Results

Generation of cells with temperature sensitive Src (tsSrc) kinase activity in the presence or absence of Pdpn expression

Pdpn has been identified as a functionally relevant biomarker and potential chemotherapeutic target for a variety of cancers. The Src tyrosine kinase induces Pdpn expression in order to promote tumor cell invasion and metastasis 8–10,21. Indeed, Pdpn signaling can account for the increase in motility resulting from oncogenic Src transformation 4. We developed a panel of cells to evaluate the effects of Pdpn on cell growth and invasion. We utilized homozygous null Pdpn knockout (PdpnKo) cells to serve as a clear background on which to examine the effects of Pdpn on transfectants derived from a common parental cell line. Studies with this system, which include homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with parental vectors (PdpnKO cells) or constructs to restore Pdpn expression (PdpnWT cells), indicate that Pdpn signaling can increase cell motility but not anchorage independent growth of nontransformed cells 14,15. However, the effects of Src kinase activity on anchorage independent growth and motility in the absence of Pdpn expression have not been evaluated. Here we utilized cells with and without Pdpn expression to answer this question. We transfected these cells with a temperature sensitive Src kinase to evaluation its effects on the same cells, thus minimizing the effects of clonal variation in this study.

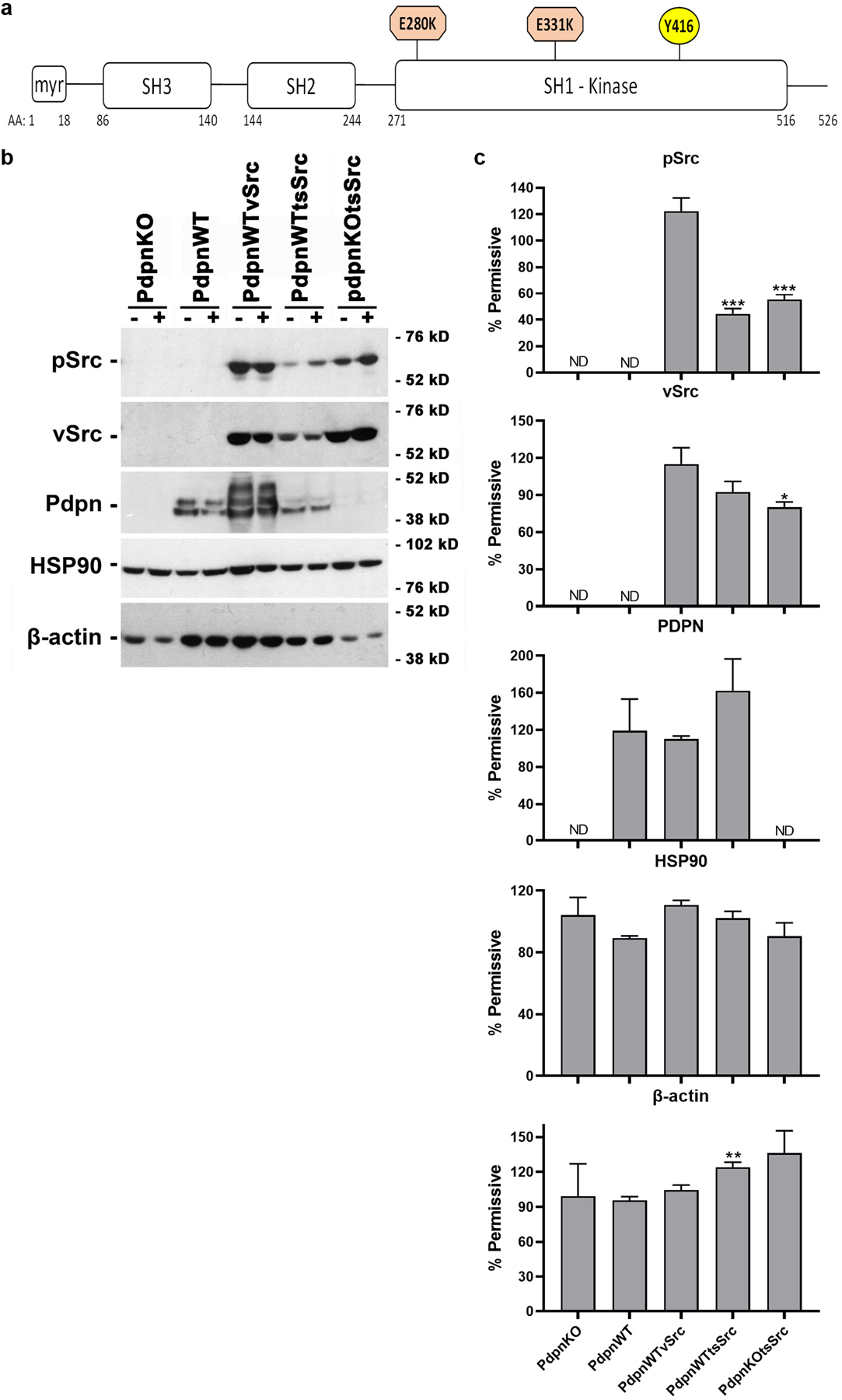

We constructed a Src kinase expression vector with glutamine to lysine mutations at amino acids 280 and 331. These substitutions generated a temperature sensitivity Src (tsSrc) kinase as shown in Figure 1a 16. We transfected this tsSrc construct into cells with (PdpnWT) or without (PdpnKO) Pdpn expression to create PdpnWTtsSrc and PdpnKOtsSrc, respectively. These cells were also transfected with empty parental vector, and PdpnWT cells were transfected with vSrc to create PdpnWTvSrc cells as controls. Western blot analysis was used to confirm Pdpn expression in the appropriate cells as shown in Figure 1b.

Figure 1: Temperature sensitive Src (tsSrc) kinase activity at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures.

(a) A temperature sensitive Src (tsSrc) construct containing Glu to Lys substitutions at aa 280 and 331 in the vSrc kinase domain was generated and analyzed by phosphorylation at Tyr416. (b) Homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with expression constructs encoding Pdpn (PdpnWT), Pdpn and vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc), tsSrc and Pdpn (PdpnWTtsSrc), tsSrc (PdpnKOtsSrc), or empty parental vectors (PdpnKO) were incubated at the 39°C nonpermissive (−) or 34°C permissive (+) temperature for 24 hours and analyzed by western blotting to detect pSrc (active Src phosphorylated at Tyr416), vSrc, Pdpn, HSP90, and β-actin with migration of molecular weight markers as indicated. (c) Protein was quantitated by image densitometry and shown as the percent of signal at the permissive temperature with single, double, and triple asterisks indicating p<0.05, p<0.01, and p<0.001 by t-test, and ND indicating not detected, respectively (mean+SEM, n=3).

Western blot analysis was used to evaluate total vSrc expression and Src kinase activity by phosphorylation at Tyr416 as previously described and indicated in Figure 1a 4,14,15. These data indicate that while total vSrc expression levels were not significantly affected by temperature shift, Src kinase activity was approximately 2 fold higher in cells expressing tsSrc grown for 24 hours at the permissive (34°C) temperature than nonpermissive (39°C) temperature. This effect was seen in tsSrc transformed cells that expressed (PdpnWTtsSrc) or did not express (PdpnKOtsSrc) Pdpn as shown in Figure 1b and 1c. In contrast, Src activity in cells transformed with constitutively active vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc) was not affected by this temperature shift. Moreover, Pdpn expression was comparable between cells grown at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. HSP90 expression levels were also not significantly affected by this temperature shift indicating that growth the nonpermissive temperature did not trigger a significant heat shock response in these cells as shown in Figure 1b and 1c 22. Taken together, these data indicate that tsSrc kinase activity was effectively controlled by temperature shift in these cells without affecting Pdpn or HSP90 expression.

Src does not require Pdpn to alter cell morphology and promote anchorage independent growth

Phase contrast microscopy was used to evaluate the effects of Src kinase activity on cell morphology. Nontransformed cells with (PdpnWT) or without (PdpnKO) Pdpn expression displayed a flattened morphology typical of a contact inhibited monolayer at both permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. In contrast, vSrc transformed PdpnWTvSrc cells displayed a disorganized refractive morphology with areas of multilayered growth at both temperatures. Cells with (PdpnWTtsSrc) or without (PdpnKOtsSrc) Pdpn expression transfected with tsSrc displayed this transformed morphology at the permissive but not non permissive temperatures as shown in Figure 2a. Results from fluorescent imaging indicate that these Src induced morphological changes correlated with disruption of cytoskeletal actin fiber organization as shown in Figure 2b. These data indicate that Src did not require Pdpn to alter the morphology of these cells.

Figure 2: Morphology of Src transformed cells with and without Pdpn expression.

Confluent monolayers of homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with expression constructs encoding Pdpn (PdpnWT), Pdpn and vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc), Pdpn and tsSrc (PdpnWTtsSrc), tsSrc (PdpnKOtsSrc), or empty parental vectors (PdpnKO) were incubated at nonpermissive (39°C) and permissive (34°C) temperatures for 72 hours. (a) Live cells were visualized by phase contrast microscopy (bar=50 microns). (b) Cells were fixed and stained with phalloidin-Texas Red and Hoechst to visualize actin and nuclei as indicated. Arrows indicate examples of organized cytoskeletal actin fibers in nontransformed cells and tsSrc transformed cells at the nonpermissive temperature (bar=50 microns).

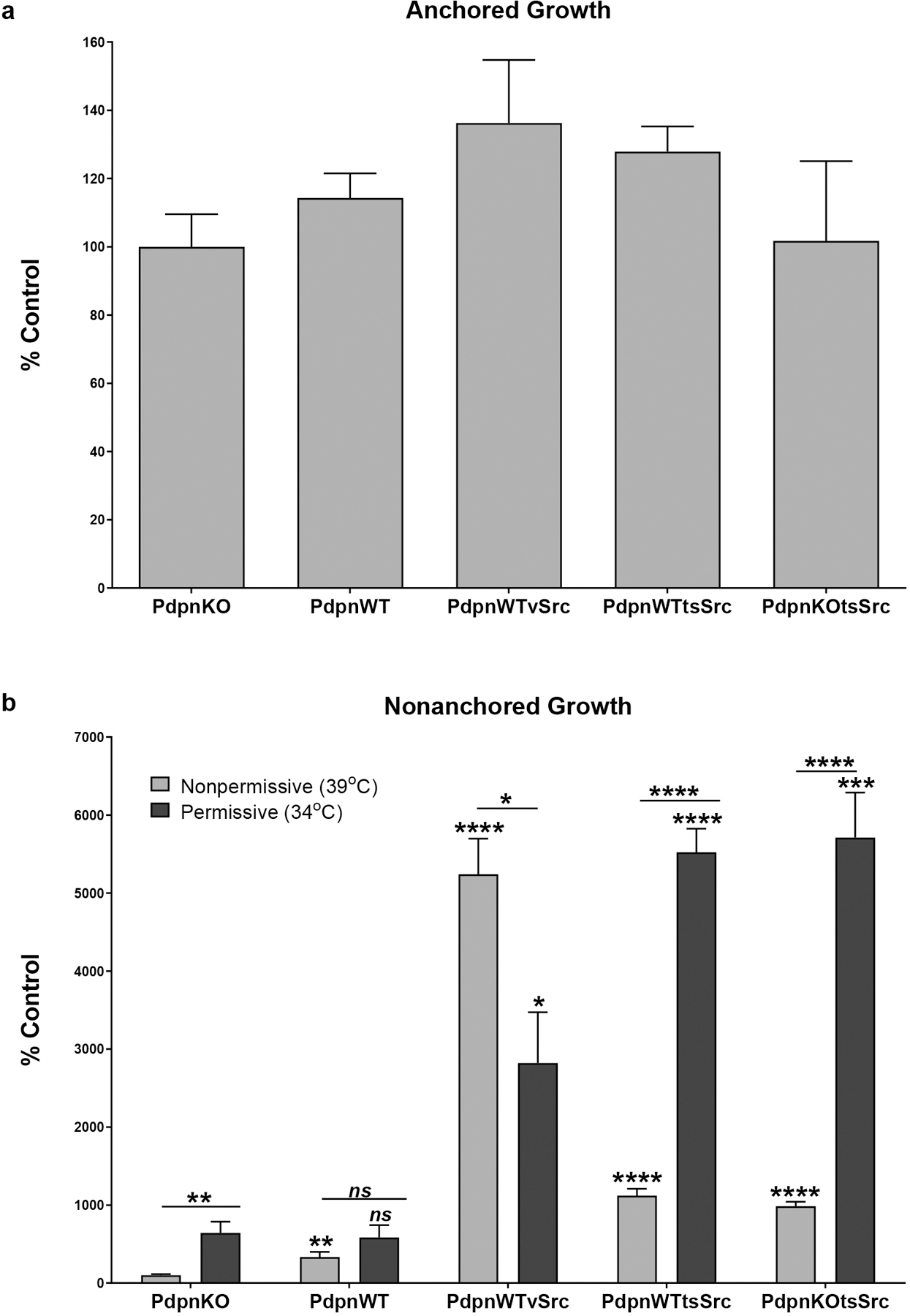

Having found that Src can transformed cell morphology independent of Pdpn expression, we sought to evaluate the effects of Pdpn on anchorage independent cell growth. Cells were plated at the nonpermissive temperature on standard culture dishes to control for plating efficiency as shown in Figure 3a, and then grown at the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures for 7 days. As expected, nontransformed PdpnKO and PdpnWT cells exhibited only minimal levels of anchorage dependent cell growth. While there was a general tendency for Pdpn to enhance nonanchored growth of these cells, this was limited to an increase of less than 4 fold as shown in Figure 3b. In contrast to these nontransformed cells, nonanchored vSrc transformed PdpnWTvSrc cells grew over 25 fold and 50 fold better than nontransformed control cells at the permissive (34°C) and nonpermissive (39°C) temperatures, respectively. These data indicate that nonanchored vSrc transformed cells were anchorage independent and grew better at 39°C than 34°C. Nonanchored tsSrc transformed cells grew as well at 34°C as vSrc transformed cells grew at 39°C. However, in contrast to vSrc transformed cells which grew about 2 fold better at 39°C than 34°C, nonanchored tsSrc transformed with (PdpnWTtsSrc) and without (PdpnKOtsSrc) Pdpn grew over 5 times more at the 34°C permissive temperature than at the 39°C nonpermissive temperature. This is consistent with the tsSrc kinase being more active at the permissive temperature as shown in Figure 1. Most importantly these cells grew at similar levels indicating that Pdpn did not affect Src directed nonanchored growth. These data indicate that Src did not require Pdpn to promote anchorage independent growth of transformed cells.

Figure 3: Src does not require Pdpn to promote anchorage independent cell growth.

Twenty thousand homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with expression constructs encoding Pdpn (PdpnWT), Pdpn and vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc), Pdpn and tsSrc (PdpnWTtsSrc), tsSrc (PdpnKOtsSrc), or empty parental vectors (PdpnKO) were grown as anchored or suspension cultures for 20 hours at the nonpermissive temperature (39°C) as indicated. (a) Anchored cells were then counted to verify plating efficiency and cell viability. (b) Suspended cells were subsequently incubated at the nonpermissive (39°C) or permissive temperature (34°C) for an additional 7 days and counted. Data are shown as percent of nontransformed PdpnKO control cells at the nonpermissive temperature with single, double, triple, and quadruple asterisks indicating p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.001, and p<0.0001 by t-test, respectively (mean+SEM, n=6).

Src requires Pdpn to promote transformed cell motility

Having found that Src did not require Pdpn to increase nonanchored cell growth, we utilized wound healing migration assays to determine if Src requires Pdpn to increase transformed cell motility. Pdpn increased nontransformed cell migration in the absence of oncogenic Src activity, which is consistent with previous reports 4,14,15. Nontransformed PdpnWT cell which express Pdpn migrated at least 2 fold more than Pdpn deficient PdpnKO cells at both the permissive and nonpermissive temperatures as shown in Figure 4a and 4b. PdpnWTvSrc cells, which constitutively express both Pdpn and vSrc kinase, also migrated at least 3 fold more than nontransformed controls at both temperatures. Interestingly, PdpnWTtsSrc cells, which express tsSrc and Pdpn, migrated just as well as vSrc transformed cells regardless of temperature. Although there was some tendency for these cells to migrate more at the 34°C permissive temperature then the 39°C nonpermissive temperature, this difference was not significant. These data indicate that Src activity did not contribute to the motility of these cells, which was driven by constitutive Pdpn expression. Moreover, migration of Src transformed PdpnKOtsSrc cells, which express tsSrc but not Pdpn, was equivalent to nontransformed Pdpn deficient control cells at both permissive and nonpermissive temperatures as shown in Figure 4a and 4b. Therefore, while Pdpn did not require Src kinase activity to increase cell migration, Src did require Pdpn to enhance cell migration. Results from Transwell invasion assays confirm these wound healing migration results. Nontransformed (PdpnWT) and tsSrc transformed (PdpnWTtsSrc) cells that express PDPN moved through membranes with 8 micron pores at least 2 times more than PDPN deficient nontransformed (PdpnKO) or tsSrc transformed (PdpnKOtsSrc) cells at the permissive (34°C) temperature as shown in Figure 4c. Taken together with growth assays, these data indicate that Src requires Pdpn as an effector to promote to cell motility, but can utilize other effectors to alter cell morphology and increase anchorage independent growth.

Figure 4: Src requires Pdpn to increase cell migration.

(a) Cell migration was assessed by wound healing assays on confluent monolayers of homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with expression constructs encoding Pdpn (PdpnWT), Pdpn and vSrc (PdpnWTvSrc), Pdpn and tsSrc (PdpnWTtsSrc), tsSrc (PdpnKOtsSrc), or empty parental vectors (PdpnKO) incubated at nonpermissive (39°C) and permissive (34°C) temperatures. Images were taken at 0 hours and 18 hours after wounding as indicated (bar=220 microns). (b) The number of cells that migrated into the wound center were quantitated as the percent of nontransformed PdpnKO cells at the nonpermissive temperature with single, double, and triple asterisks indicating p<0.05, p<0.01, and p<0.001 by t-test, respectively (mean+SEM, n=6). (c) Cell invasion was assessed by Transwell invasion assays at the permissive temperature. The percent of cells that migrated from the top to the bottom of the membrane in 24 hours were normalized to the percent of nontransformed PdpnKO cells with ns, single, and double asterisks indicating p>0.05, p<0.05, and 0.01 by t-test, respectively (mean+SEM, n=3).

Persistent Src kinase activity is required to maintain transformed cell morphology

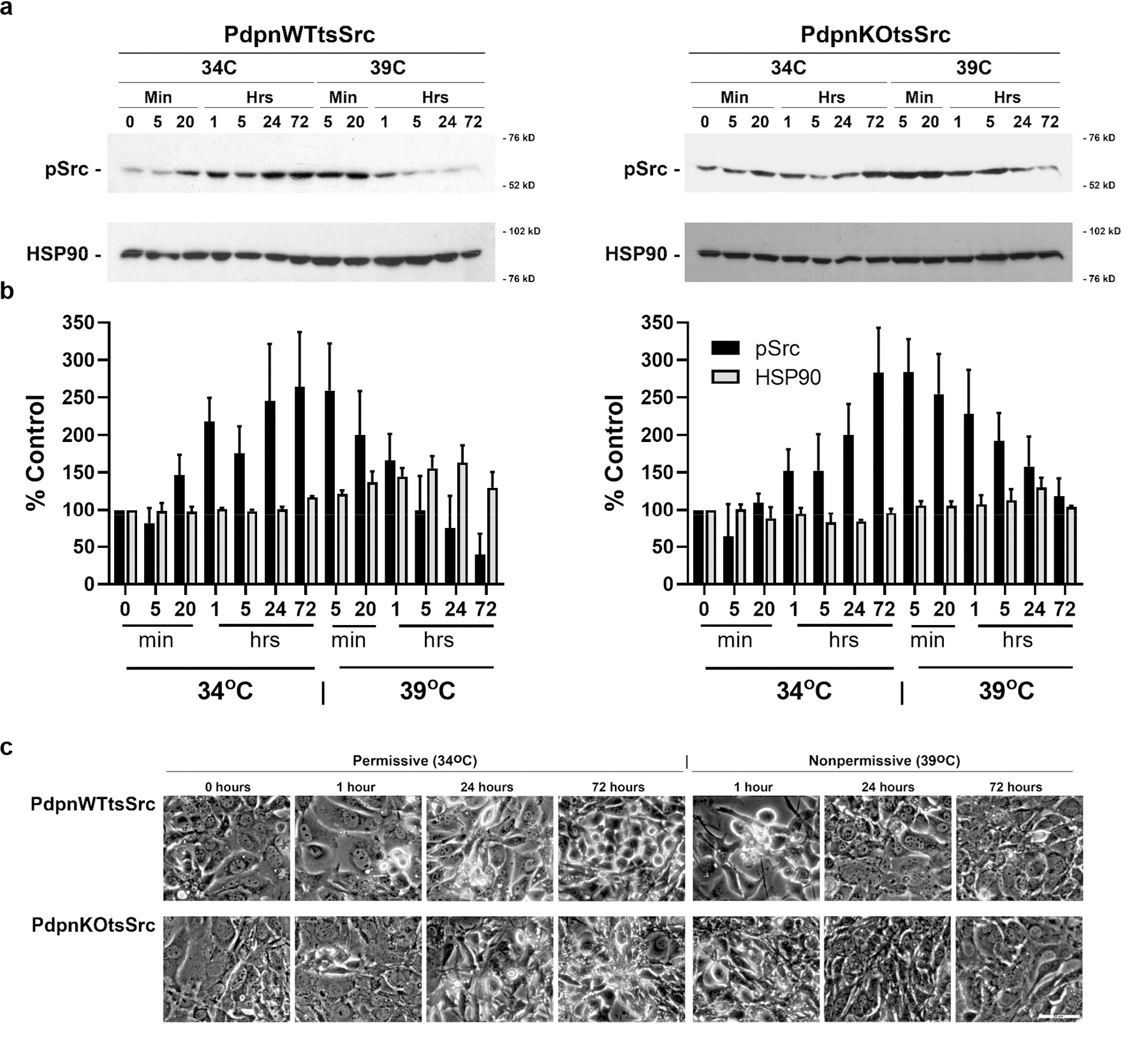

Src transformation is a dynamic process. For example, effects of Src on cell morphology and phenotype can be reversed by contact normalization mediated by contact with neighboring nontransformed cells, and inhibition of Pdpn expression has been identified as a key event in this process 4,8. We, therefore, sought to evaluate the utility of our tsSrc transformed cells to investigate temporal events leading to Src transformation and its reversal by temperature shift in cells with and without Pdpn expression. Results from Western blot analysis indicate that tsSrc activity increased greater than 50% compared to controls within 20 minutes of shift from the 39°C nonpermissive temperature to the 34°C permissive temperature, and reached peak levels exceeding 250% of controls by 72 hours after this temperature shift. This increased Src kinase activity was reversed to about 150% of control levels within 1 hour, and completely reversed to control levels within 24 hours after return to the 39°C nonpermissive temperature as shown in Figure 5a and 5b. This temperature shift did not affect HSP90 expression, which was used as a loading control and heat shock indicator for these assays. Modulation of Src kinase activity was accompanied by transformation of cell morphology to a refractive phenotype within 24 hours of Src activation at 34°C permissive temperature, and reversed to a flattened morphology typical of a contact inhibited monolayer within 24 hours after return to the 39°C nonpermissive temperature as shown in Figure 5c. Similar results were seen in both PdpnKOtsSrc and PdpnWTtsSrc cells, indicating that Src activity is required to maintain transformed cell morphology independent of Pdpn expression.

Figure 5: Src activity is required for cells to maintain transformed morphology independent of Pdpn expression.

Confluent monolayers of homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with tsSrc and Pdpn (PdpnWTtsSrc) or empty vector (PdpnKOtsSrc) were incubated at the nonpermissive temperature (39°C) for 48 hours, followed by growth at the permissive temperature (34°C) for 72 hours, and then shifted back to the nonpermissive temperature for an additional 72 hours. (a) Total protein was obtained from cells and analyzed for active tsSrc (phosphorylated at Tyr416) and HSP90 expression by western blotting. Migration of molecular weight markers is indicated in kD. (b) Protein was quantitated by image densitometry and presented as percent of initial signal at 48 hours growth at the permissive temperature (zero-minute timepoint) for each protein (mean+SEM, n=3). (c) Phase contrast images at indicated timepoints and temperatures (bar= 50 microns).

Pdpn modulates Src mediated protein phosphorylation events

We performed phosphopeptide analysis to investigate the effects of Pdpn on Src mediated phosphorylation events. This analysis detected a total of 13629 phosphopeptides in tsSrc transformed cells. Of these, phosphorylation of 782 peptides was at least 50% higher in both PdpnKOtsSrc and PdpnWTtsSrc cells cultured at the permissive than nonpermissive temperature. These phosphopeptides include several sites on the Src protein itself. Consistent with data from Western blotting with phosphospecific antibodies shown in Figure 1, Tyr416 phosphorylation in both PdpnKOtsSrc and PdpnWTtsSrc cells was approximately 2 fold higher at the permissive than nonpermissive temperature as shown in Figure 6a. These data also found more phosphorylation of the Src kinase substrate Cx43 gap junction protein 23,24 at Tyr137 and Tyr247 at the permissive than nonpermissive temperature in both PdpnKOtsSrc and PdpnWTtsSrc cells as shown in Figure 6b. However, in contrast to Src autophosphorylation and Cx43 phosphorylation, Src activation caused more phosphorylation in Pdpn deficient PdpnKOtsSrc cells than in PdpnWTtsSrc cells at Tyr184 and Ser209 in the SH2 domain, and Tyr382 and Tyr436 in the kinase domain as shown in Figure 6. These data indicate that Pdpn might act to suppress Src driven phosphorylation events, including those mediated by downstream serine kinases. Moreover, in addition to the 782 phosphopeptides increased by Src activation in both PdpnKOtsSrc and PdpnWTtsSrc cells, an additional 838 peptides were phosphorylated at least 50% more in Pdpn deficient PdpnKOtsSrc cells at the permissive than nonpermissive temperature. In contrast, only 81 peptides were phosphorylated at least 50% more in PdpnWTtsSrc cells at permissive than nonpermissive temperature. Of these 81 peptides, 27 proteins were phosphorylated at least 50% more in PdpnWTtsSrc cells than PdpnKOtsSrc cells at the permissive compared to nonpermissive temperature. These proteins include potential tumor promotors and tumor suppressors as shown in Table 1.

Figure 6: Pdpn modulates phosphorylation events on Src.

Protein from confluent monolayers of homozygous null Pdpn knockout cells transfected with tsSrc and Pdpn (PdpnWTtsSrc) or empty vector (PdpnKOtsSrc) were incubated at nonpermissive (39°C) or permissive (34°C) temperatures for 24 hours was analyzed by phosphopeptide mass spectroscopy. (a) Phosphorylation sites on tsSrc with schematic showing glutamate to lysine mutations along with myristoylation, SH1 (kinase), SH2, and SH3 domains. Phosphorylation at Y416 might also be detected by similar peptides from Yes and Fyn kinase. (b) Phosphorylation sites on Cx43 with schematic showing intracellular (IC), extracellular (EC), and transmembrane domains. Data are shown as the percent phosphorylation of the corresponding cell line at the nonpermissive temperature as indicated (mean+SEM, n=2). Values from PdpnWTtsSrc and PdpnKOtsSrc cells at the permissive temperature were compared to each other with ns, single, double, triple, and quadruple asterisks indicating p>0.05, p<0.05, p<0.01, p<0.001, and p<0.0001 by t-test, respectively.

Table 1: Pdpn modulates Src kinase mediated phosphorylation events.

Protein symbol, name, and phosphorylation sites are shown along with difference of induction (Δ Induction) shown as a ratio of phosphorylation events in PdpnWTstSrc cells at permissive (34°C)/nonpermissive (39°C) temperatures over phosphorylation events seen in PdpnKOtsSrc cells at permissive (34°C)/nonpermissive (39°C) temperatures (mean, n=2). Some phosphorylation events can be attributed to more than one protein as indicated.

| Symbol | Name | Annotated Sequence | Δ Induction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rbl2 | RB transcriptional corepressor like 2 | 624-YSS*PTVSTTR-633 | 2.2 |

| Parp12 | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family member 12 | 457-NLVYGT*IR-464 | 2.1 |

| Rftn1 | Raftlin | 481-QGS*AAVQNGPAGHNR-495 | 2.1 |

| Rab11fip3 | RAB11 family interacting protein 3 | 937-SSS*LGLQEYNSR-948 | 1.9 |

| Chaf1a | chromatin assembly factor 1 subunit A | 290-GGRSSPST*PACR-301 | 1.8 |

| Cirbp | cold inducible RNA binding protein | 146-SQGGS*YGYR-154 | 1.8 |

| Nelfa | negative elongation factor complex member A | 225-SPTTPSVFS*PSGNR-238 | 1.7 |

| Rbm3 | RNA binding motif protein 3 | 115-YDS*RPGGYGYGYGR-128 | 1.7 |

| Pcnt | Pericentrin | 2680-QDGTDLQSS*LR-2690 | 1.6 |

| Gas2l1 | growth arrest-specific 2 like 1 | 371-SDDSATGS*RR-380 | 1.6 |

| Micall2 | MICAL-like 2 | 638-S*PSIS*PR-644 | 1.6 |

| Matr3 | matrin 3 | 252-FDSEY*ER-258 | 1.6 |

| Myh11 Myh9 Myh14 |

myosin heavy polypeptide 11 myosin heavy polypeptide 9 myosin heavy polypeptide 14 |

556-ATDKS*FVEK-564 537-ATDKS*FVEK-545 567-ATDKS*FVEK-575 |

1.6 |

| Hectd1 | HECT domain E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 | 1563-TNATNNMNLS*R-1573 | 1.6 |

| Champ1 | chromosome alignment maintaining phosphoprotein 1 | 582-CDSLAQEGLLAT*PK-595 | 1.6 |

| Cd44 | CD44 antigen | 304-KLVINGGNGT*VEDR-317 | 1.6 |

| Lin54 | lin-54 DREAM MuvB core complex component | 307-IAIS*PLKS*PNK-317 | 1.6 |

| Epb41 | erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 | 712-RLS*THS*PFR-720 | 1.6 |

| Kdm3b | KDM3B lysine (K)-specific demethylase 3B | 308-GEVDSNGS*DGGEASR-322 | 1.6 |

| Flrt3 | fibronectin leucine rich transmembrane protein 3 | 582-KDNS*ILEIR-590 | 1.6 |

| Scarf2 | scavenger receptor class F member 2 | 467-RELT*LGR-473 | 1.6 |

| Ogdh Ogdhl |

oxoglutarate dehydrogenase oxoglutarate dehydrogenase-like |

457-SS*PYPTDVAR-466 444-SS*PYPTDVAR-453 |

1.6 |

| E2f8 | E2F transcription factor 8 | 142-AESSQNS*PPVPNK-154 | 1.5 |

| Adnp | activity-dependent neuroprotective protein | 95-NVHS*EDFENR-104 | 1.5 |

| Fads2 | fatty acid desaturase 2 | 4-GGNQGEGS*TER-14 | 1.5 |

| Mybbp1a | MYB binding protein 1a | 1215-DQPPS*T*GKK-1223 | 1.5 |

| Dtl | denticleless E3 ubiquitin protein ligase | 671-AENSSPRS*PSSQTPSSR-687 | 1.5 |

Discussion

The Src kinase phosphorylates adapter proteins, namely p130Cas/BCAR1, in order to increase Pdpn expression, cell motility, and anchorage independent growth 6,8,25. Results from studies with nontransformed cells indicate that Pdpn can increase cell mobility, but not anchorage independent growth, in the absence of oncogenic Src kinase activity 4,10,14,15. However, the effects of Src on motility and nonanchored cell growth in the absence of Pdpn expression have not yet been reported. This study utilized a temperature sensitive Src kinase (tsSrc) in cells with and without Pdpn expression to address this question. Results from Western blot and phosphoproteomic analysis indicate that tsSrc activity was equivalent to constitutively active vSrc at the permissive (34°C) temperature, and reduced to about half of this level at the nonpermissive (39°C) temperature. This change in activity was reversible and occurred within 1 hour, with maximal effect seen up to 72 hours, after temperature shift. These data are consistent with previous studies that employed temperature sensitive Src constructs to investigate the effects of oncogenic kinase signaling that can be turned on and off in the same cells 26–28.

Src kinase activity causes a pronounced effect on cell morphology 4,13,18,29,30. Cells expressing tsSrc assumed a disorganized and refractive morphology typical of transformed cells at the permissive temperature, while they assumed a flattened morphology in contact inhibited monolayers typical of nontransformed cells at the nonpermissive temperature. These changes occurred regardless of PDPN expression, indicating that Src does not require PDPN to disrupt cell shape. This effect could be reversed since tsSrc transformed cells assumed a nontransformed morphology after temperature shift to the nonpermissive temperature. However, it is not clear if this change in cell morphology occurs within the lifetime of a cell, or if division is required for the cell to assume a normal or transformed shape as a result of Src kinase activity. Video microscopy could be employed in future experiments to elucidate the dynamic effects of Src kinase on cell morphology in this system.

In addition to cell morphology, results from this study indicate that Src did not require PDPN to increase nonanchored cell growth. Previous reports indicate that Pdpn expression does not increase anchorage independent cell growth in the absence of oncogenic Src kinase activity 4. However, it was not clear if Src can promote anchorage independent growth in the absence of Pdpn expression. In this study, cells expressing tsSrc with or without Pdpn expression displayed a 5 fold increase in anchorage independent growth at the permissive temperature compared to the nonpermissive temperature. These data indicate that Src can promote nonanchored cell growth independent of Pdpn expression.

In contrast to cell morphology and nonanchored growth, results from this study indicate that Src does require Pdpn to increase cell migration. Results from previous studies indicate that Src induces Pdpn expression in order to promote cell migration 4,6. Moreover, Pdpn can increase nontransformed cell migration in the absence of oncogenic Src kinase activity 4,6,14,15. However, effects of Src on cell motility in the absence of Pdpn expression are not described in these previous reports. As expected, Pdpn expression increased cell motility in this study. Exogenous Pdpn expression increased nontransformed and tsSrc transformed cell migration by over 2 fold and 3 fold compared to Pdpn deficient knockout cells, respectively. However, Src kinase activity did not affect migration of these cells. Src activation did not cause a significant difference in the motility of tsSrc transformed cells at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures regardless of Pdpn an expression. More importantly, Src activation did not affect the motility of Pdpn deficient cells. tsSrc transformed Pdpn deficient knockout (PdpnKOtsSrc) cells migrated equivalent to nontransformed PdpnKo cells, and at least 3 fold lower than transformed or nontransformed cells expressing Pdpn at permissive and nonpermissive temperatures. These results indicate that, while Pdpn does not require Src kinase activity to increase cell migration, Src does require Pdpn to increase cell migration. Indeed, total and active Src levels were at least as high in PdpnKOtsSrc cells compared to PdpnWTtsSrc cells (see Figure 1) indicating that effects seen on cell growth and morphology were mediated downstream of Src activity.

Ultimately, Src phosphorylates effectors to modulate motility and anchorage independent cell growth. We utilized phosphoproteomics to investigate the effect of Pdpn on these phosphorylation events. We focused on Src induced phosphorylation events in this study. Hypophosphorylation motifs are not described here, but can be accessed at MassIVE MSV000088244. Src activity increased phosphorylation of about 12% (1620) of the nearly 14 thousand phosphopeptides identified in this study by at least 1.5 fold. Of these, only 81 peptides were phosphorylated more in tsSrc transformed cells expressing Pdpn (PdpnWTtsSrc cells) at the permissive temperature than nonpermissive temperature, and only 27 proteins were phosphorylated at least 1.5 fold more in PdpnWTtsSrc cells than PdpnKOtsSrc cells at the permissive compared to nonpermissive temperature. Therefore, about 0.2% (28) of the protein phosphorylation events mediated by Src appear to rely on Pdpn signaling. These proteins include retinoblastoma-like protein 2 (RBL2) tumor suppressor, CD44 cell surface protein, and matrin 3 (Matr3) nuclear protein.

Pdpn increased RBL2 phosphorylation at S626 in this study (see Table 1). RBL2 phosphorylation by cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs), glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GS3K), and AKT/PKB has been found to inhibit RBL2 activity and promote promotes cell cycle progression 31,32. For example, CDK4/6 can phosphorylate human RBL2 on S672, which is cognate to mouse S626 we found in this study, to promote osteosarcoma cell proliferation 33,34. These data suggest that Pdpn might work with Src to increase RBL2 phosphorylation by CDK in order to promote cell cycle progression.

The CD44 receptor interacts with Pdpn and Src to promote cell motility 10,35. We found that Src and Pdpn cooperate to enhance CD44 phosphorylation at T313 (see Table 1). Increased phosphorylation of this site can be induced by IL33 signaling in macrophages 36. Cytoplasmic CD44 serine and threonine phosphorylation has also be reported to promote mammary carcinoma cell migration in response to hyaluronic acid and TGFβ signaling 37.

Matr3 was the only protein found to be phosphorylated on tyrosine in response to Src in a Pdpn dependent manner. We found only Y256 to be phosphorylated in this study (see Table 1). Phosphorylation of his site has been reported in response to Src and IL33 signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts and macrophages, respectively. This phosphorylation site lies in a P85_SH2 consensus site targeted by phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 (PIK3R1) mediated kinase phosphorylation 36,38. PIK3R1 is an 85 kD regulatory subunit of PI3K that mediates peptide phosphorylation by receptor tyrosine kinases including FGFR, KIT, PDGFR, and Ret to promote cell survival and proliferation 39–41. Accordingly, Matr3 has been found to increase survival and growth of melanoma and oral squamous cell carcinoma cells 42,43. Matr3 phosphorylation at a predicted tyrosine kinase consensus site at Y214 was not detected in our analysis, possibly due to its peptide fragment properties resulting from trypsin digestion.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the effects of oncogenic Src kinase activity on cell motility and anchorage independent growth in Pdpn knockout cells. Results from this study clearly indicate that Src promotes anchorage independent growth independent of Pdpn, and that Pdpn promotes cell migration independent of oncogenic Src kinase activity. Therefore, although Src induces Pdpn expression to promote cell motility in a serial manner, Src and Pdpn act in parallel to promote cancer progression. Src increases nonanchored growth while Pdpn drives tumor cell motility. However, results from our phosphoproteomic studies also indicate that Pdpn augments Src mediated phosphorylation events consistent with pleiotropic effects on a variety of effectors to promote cancer progression. Indeed, Src protein interactions and potential scaffolding functions should be considered in addition to its kinase activity with respect to these signaling paradigms 1. Overall, these results clarify fundamental roles for Src and Pdpn as tumor promoters, and support efforts that utilize Pdpn as a functionally relevant biomarker and chemotherapeutic target to detect and treat cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by funding from an NIH shared instrumentation grant S10OD025140 to Peter Lobel (Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), and the Osteopathic Heritage Foundation, Camden Health Research Initiative, New Jersey Health Foundation grant PC11-21CV, and NIH grant CA235347 to GSG.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

GSG has intellectual property and ownership in Sentrimed, Inc. which is developing agents that target PDPN to treat diseases including cancer and arthritis. Other authors have no conflicts to declare.

References

- 1.Ortiz MA, Mikhailova T, Li X, Porter BA, Bah A, Kotula L. Src family kinases, adaptor proteins and the actin cytoskeleton in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Commun Signal 2021;19(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martellucci S, Clementi L, Sabetta S, Mattei V, Botta L, Angelucci A. Src Family Kinases as Therapeutic Targets in Advanced Solid Tumors: What We Have Learned so Far. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belli S, Esposito D, Servetto A, Pesapane A, Formisano L, Bianco R. c-Src and EGFR Inhibition in Molecular Cancer Therapy: What Else Can We Improve? Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen Y, Chen CS, Ichikawa H, Goldberg GS. SRC induces podoplanin expression to promote cell migration. JBiolChem 2010;285(13):9649–9656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg GS, Alexander DB, Pellicena P, Zhang ZY, Tsuda H, Miller WT. Src phosphorylates Cas on tyrosine 253 to promote migration of transformed cells. JBiolChem 2003;278:46533–46540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue H, Miyazaki Y, Kikuchi K, et al. Podoplanin promotes cell migration via the EGF-Src-Cas pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. JOral Sci 2012;54(3):241–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii M, Honma M, Takahashi H, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Intercellular contact augments epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-activation which increases podoplanin-expression in order to promote squamous cell carcinoma motility. Cellular signalling 2013;25(4):760–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krishnan H, Miller WT, Blanco FJ, Goldberg GS. Src and podoplanin forge a path to destruction. Drug Discov Today 2019;24(1):241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan H, Rayes J, Miyashita T, et al. Podoplanin: An emerging cancer biomarker and therapeutic target. Cancer science 2018;109(5):1292–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quintanilla M, Montero-Montero L, Renart J, Martin-Villar E. Podoplanin in Inflammation and Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda H, Oda H, Nakamoto T, et al. Cardiovascular anomaly, impaired actin bundling and resistance to Src-induced transformation in mice lacking p130Cas. NatGenet 1998;19(4):361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patwardhan P, Shen Y, Goldberg GS, Miller WT. Individual Cas phosphorylation sites are dispensable for processive phosphorylation by Src and cellular transformation. JBiolChem 2006;281:20689–20697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen Y, Jia Z, Nagele RG, Ichikawa H, Goldberg GS. SRC uses Cas to suppress Fhl1 in order to promote nonanchored growth and migration of tumor cells. Cancer Research 2006;66(3):1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan H, Retzbach EP, Ramirez MI, et al. PKA and CDK5 can phosphorylate specific serines on the intracellular domain of podoplanin (PDPN) to inhibit cell motility. Exp Cell Res 2015;335(1):115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krishnan H, Ochoa-Alvarez JA, Shen Y, et al. Serines in the intracellular tail of podoplanin (PDPN) regulate cell motility. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013;288(17):12215–12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maroney AC, Qureshi SA, Foster DA, Brugge JS. Cloning and characterization of a thermolabile v-src gene for use in reversible transformation of mammalian cells. Oncogene 1992;7(6):1207–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa-Alvarez JA, Krishnan H, Pastorino JG, et al. Antibody and lectin target podoplanin to inhibit oral squamous carcinoma cell migration and viability by distinct mechanisms. Oncotarget 2015;6(11):9045–9060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheehan SA, Retzbach EP, Shen Y, Krishnan H, Goldberg GS. Heterocellular N-cadherin junctions enable nontransformed cells to inhibit the growth of adjacent transformed cells. Cell Commun Signal in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batth TS, Francavilla C, Olsen JV. Off-line high-pH reversed-phase fractionation for in-depth phosphoproteomics. Journal of proteome research 2014;13(12):6176–6186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mertins P, Qiao JW, Patel J, et al. Integrated proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications by serial enrichment. Nat Methods 2013;10(7):634–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Retzbach EP, Sheehan SA, Nevel EM, et al. Podoplanin emerges as a functionally relevant oral cancer biomarker and therapeutic target. Oral oncology 2018;78:126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagaraj NS, Singh OV, Merchant NB. Proteomics: a strategy to understand the novel targets in protein misfolding and cancer therapy. Expert Rev Proteomics 2010;7(4):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding VM, Boersema PJ, Foong LY, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation profiling in FGF-2 stimulated human embryonic stem cells. PloS one 2011;6(3):e17538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pahujaa M, Anikin M, Goldberg GS. Phosphorylation of connexin43 induced by Src: Regulation of gap junctional communication between transformed cells. Experimental Cell Research 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan H, Goldberg GS. Contact normalization or escape from the matrix. In: Kandous M, ed. Intercellular communication and cancer Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2015:297–342. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochoa-Alvarez JA, Krishnan H, Shen Y, et al. Plant lectin can target receptors containing sialic Acid, exemplified by podoplanin, to inhibit transformed cell growth and migration. PLoSONE 2012;7(7):e41845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Y, Khusial PR, Li X, Ichikawa H, Moreno AP, Goldberg GS. Src utilizes Cas to block gap junctional communication mediated by connexin43. JBiolChem 2007;282:18914–18921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crow DS, Kurata WE, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 in cells containing mutant src oncogenes. Oncogene 1992;7(5):999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Shen Y, Ichikawa H, Antes T, Goldberg GS. Regulation of miRNA expression by Src and contact normalization: effects on nonanchored cell growth and migration. Oncogene 2009;28:4272–4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexander DB, Ichikawa H, Bechberger JF, et al. Normal cells control the growth of neighboring transformed cells independent of gap junctional communication and SRC activity. Cancer Research 2004;64(4):1347–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Litovchick L, Chestukhin A, DeCaprio JA. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates RBL2/p130 during quiescence. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24(20):8970–8980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pentimalli F, Forte IM, Esposito L, et al. RBL2/p130 is a direct AKT target and is required to induce apoptosis upon AKT inhibition in lung cancer and mesothelioma cell lines. Oncogene 2018;37(27):3657–3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villen J, Beausoleil SA, Gerber SA, Gygi SP. Large-scale phosphorylation analysis of mouse liver. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007;104(5):1488–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen K, Farkas T, Lukas J, Holm K, Ronnstrand L, Bartek J. Phosphorylation-dependent and -independent functions of p130 cooperate to evoke a sustained G1 block. EMBO J 2001;20(3):422–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin-Villar E, Fernandez-Munoz B, Parsons M, et al. Podoplanin Associates with CD44 to Promote Directional Cell Migration. MolBiolCell 2010;21:4387–4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto SM, Nirujogi RS, Rojas PL, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of IL-33-mediated signaling. Proteomics 2015;15(2–3):532–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bourguignon LY, Singleton PA, Zhu H, Zhou B. Hyaluronan promotes signaling interaction between CD44 and the transforming growth factor beta receptor I in metastatic breast tumor cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 2002;277(42):39703–39712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrando IM, Chaerkady R, Zhong J, et al. Identification of targets of c-Src tyrosine kinase by chemical complementation and phosphoproteomics. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2012;11(8):355–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandelker D, Gabelli SB, Schmidt-Kittler O, et al. A frequent kinase domain mutation that changes the interaction between PI3Kalpha and the membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2009;106(40):16996–17001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miled N, Yan Y, Hon WC, et al. Mechanism of two classes of cancer mutations in the phosphoinositide 3-kinase catalytic subunit. Science 2007;317(5835):239–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vainikka S, Joukov V, Wennstrom S, Bergman M, Pelicci PG, Alitalo K. Signal transduction by fibroblast growth factor receptor-4 (FGFR-4). Comparison with FGFR-1. The Journal of biological chemistry 1994;269(28):18320–18326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuriyama H, Fukushima S, Kimura T, et al. Matrin-3 plays an important role in cell cycle and apoptosis for survival in malignant melanoma. Journal of dermatological science 2020;100(2):110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nho SH, Yoon G, Seo JH, et al. Licochalcone H induces the apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via regulation of matrin 3. Oncology reports 2019;41(1):333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]