Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is characterized by its highly reactive inflammatory desmoplastic stroma with evidence of an extensive tumor stromal interaction largely mediated by inflammatory factors. KRAS mutation and inflammatory signaling promote pro-tumorigenic events including metabolic reprogramming with several inter-regulatory crosstalk to fulfill the high demand of energy and regulate oxidative stress for tumor growth and progression. Notably, the more aggressive molecular subtype of PDAC enhances influx of glycolytic intermediates. This review focuses on the interactive role of inflammatory signaling and metabolic reprogramming with emerging evidence of crosstalk, which supports the development, progression, and therapeutic resistance of PDAC. Understanding the emerging crosstalk between inflammation and metabolic adaptations may identify potential targets and develop novel therapeutic approaches for PDAC.

Keywords: Inflammatory mediators, metabolic reprogramming, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), autophagy, molecular subtype

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal malignancies with a median patient survival of ~6 months. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the major form and comprises over 95% of all malignancies in pancreas [1].

Inflammation and metabolic adaptations are described as hallmarks of cancer and are implicated in tumor development and malignant progression [2]. In pancreatic cancer, chronic inflammation and inflammatory mediators (see Glossary) play key roles in different stages of tumorigenesis [3, 4]. Chronic and hereditary pancreatitis, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and diet are some of the risk factors associated with PDAC [5] (Figure 1). A sustained generation of inflammatory mediators can accelerate mutagenesis and the accumulation of mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [4], and chronic pancreatitis is a critical event for the development of PDAC in genetically engineered mouse models [6]. Consistently, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling plays a significant role in inflammation and the progression of PDAC [4]. Moreover, pancreatic inflammation primes acinar cells for KRAS mediated transformation by inducing an extended tissue damage protective response through activation of MAPK pathway [7], which further reveals the mechanistic and functional role of inflammation in PDAC.

Figure 1. Inflammatory mediators and PDAC carcinogenesis.

Risk factors for PDAC include chronic pancreatitis, obesity, diabetes, diet, alcohol, smoking, and genetics. These risk factors can accelerate inflammation and mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Inflammatory mediators directly or indirectly induce oncogenic signaling pathways, which alters cellular growth, metabolism and differentiation resulting in growth and progression of pancreatic cancer.

Tumorigenesis reprograms numerous critical pathways necessary to acquire nutrients and synthesize metabolites to meet the high demands of tumor cells [2, 8, 9]. Like inflammation, metabolic reprogramming is reported as one of the hallmarks of cancer [2, 8, 9]. Several studies have described metabolic rewiring in PDAC as one of the key events in growth and progression of pancreatic cancer [6, 9]. However, recent studies are revealing the interactive roles between inflammation and metabolism in the development and progression of PDAC [3, 9]. Although, these two hallmarks of cancer are strongly implicated in the development of PDAC, their interaction is not well described and deserve further investigation. This review focuses on the interactions of inflammatory signaling and metabolic reprogramming in PDAC. Understanding the interactive roles of these two key biological events can help develop novel approaches for the management of PDAC.

Tumor microenvironment and genetic alterations as regulators of metabolic reprogramming

Metabolic reprogramming is induced by intrinsic drivers such as genetic alterations and by extrinsic drivers such as the tumor microenvironment (TME). Cancer cells are characterized by sustained proliferation as they enhance glycolysis, lipid and amino acid synthesis, and macromolecule biosynthesis by the induction of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [2, 8]. Due to an increased demand of energy, cancer cells shift metabolism from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to anaerobic glycolysis [2, 8]. This shift can decrease mitochondrial metabolism accompanied by reduced ROS accumulation, which enhances metastasis [10]. Genetic alterations including oncogenic KRAS mutation, which is a dominant genetic alteration in PDAC and a key driver of glycolysis, and loss/gain of oncogenic functions of tumor suppressor genes induces metabolic adaptations through multiple intracellular signaling pathways [8, 11–13], such as phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)-AKT, AMPK, MYC, and HIF-1 pathways. Furthermore, HIF-1 induces several glycolytic genes, including GLUT1/SLC2A1, hexokinase-2 (HK2), lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), and 6-phoshofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3 (PFKFB3), which enhances glycolysis and facilitates the flux of glycolytic intermediates into biosynthetic pathways [11, 12].

The TME is composed of various cells or components (e.g., pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, smooth muscle cells, neurons) [2, 8, 9]. PDAC is characterized by a highly reactive desmoplastic stroma with aberrant microenvironmental conditions (e.g., high lactate, low nutrients/pH, hypoxia, depletion of extracellular amino acids, inflammation) that contribute to the metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells [8, 9, 12, 14]. As such, in PDAC, poor vascularization and hypoxia under massive desmoplasia create a strenuous and harsh environment for cells to survive. Hypoxia and low pH force cancer cells to rewire their metabolism to maintain survival [8, 12, 23]. In this context, NHE7, a family of sodium-hydrogen exchangers, is shown to maintain pH homeostasis through Golgi acidification in PDAC [24].

Inflammatory mediators play a central role in PDAC progression by modulating the TME and contributing to PDAC desmoplastic stroma [3]. Additionally, through secretion of inflammatory mediators, growth factors, and enzymes, CAFs contribute to desmoplastic stroma, recruitment of inflammatory and immune cells into TME, and metabolic alterations [3, 15–19]. Furthermore, adipocytes, muscle cells, and hepatocytes interact with PDAC cells through IL-6 signaling [20, 21] and neurons support PDAC under serine-deprived conditions [22]. Furthermore, several immune cells (e.g., macrophages, T cells, NK cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)) undergo metabolic reprogramming and may impact on tumor progression [25]. Increased metabolisms in cancer cells, CAFs, and macrophages result in the accumulation of metabolic wastes (e.g., lactate, kynurenine, lipid, adenosine) in the TME, inducing immune cell evasion [25]. A recent study showed that macrophage-released deoxycytidine attenuated the effect of gemcitabine in PDAC cells [26].

Crosstalk between Inflammation and metabolic pathways

Oncogenic KRAS and metabolic reprogramming in PDAC

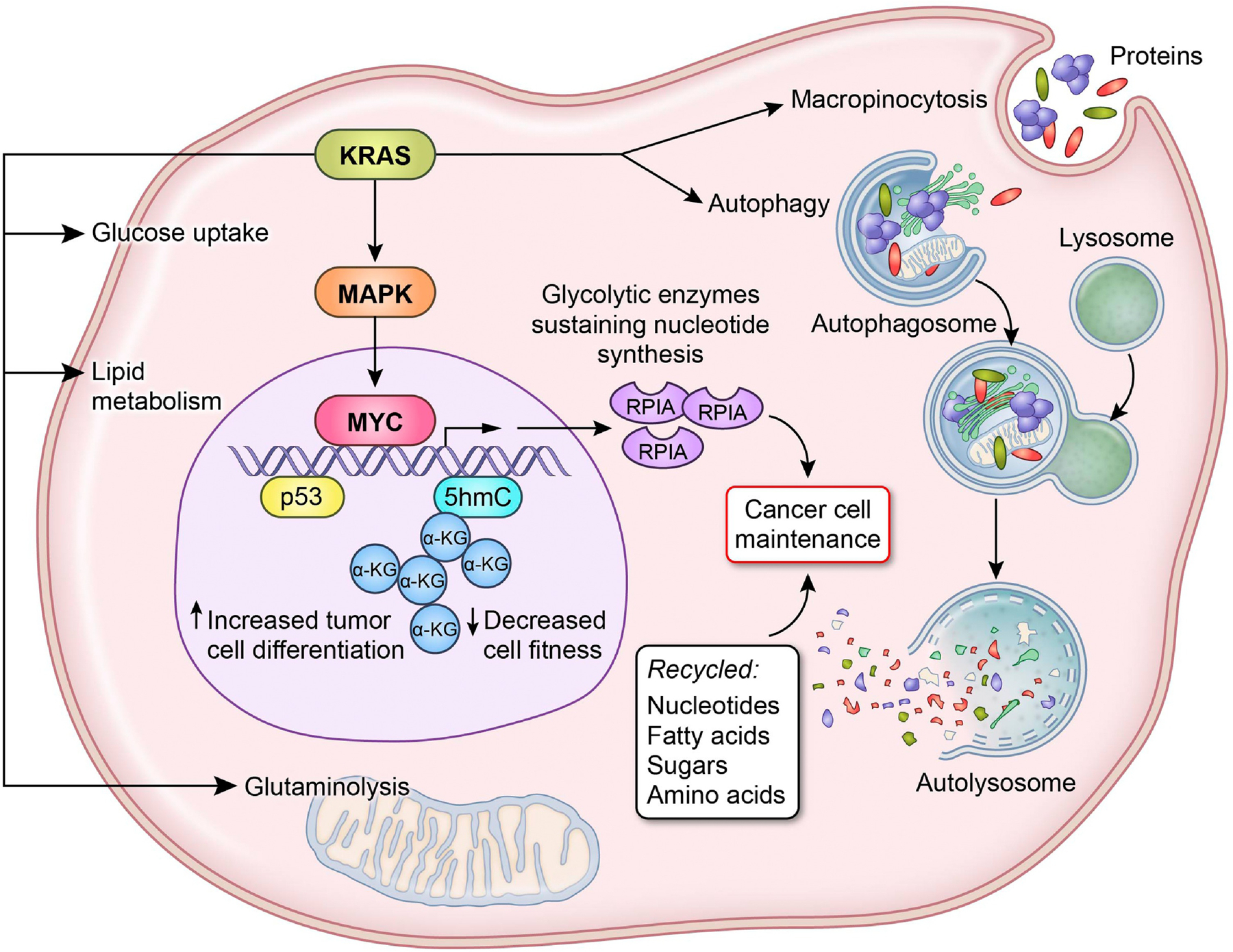

Oncogenic KRAS mutations are found in about 95% of all PDAC tumors and is required for the development of PDAC [6, 27]. KRAS mutations provide optimal conditions for cancer cells to thrive by elevating the levels of glucose and glycolytic intermediates, cellular redox potential, as well as fatty acids and glutamine uptake [6, 14, 27, 28]. Furthermore, mutant KRAS enhances macropinocytosis and amino acid turnover [6, 14, 27, 28]. PDAC cells with mutant KRAS rely on autophagy to facilitate tumor growth and survival during starvation [6, 14, 28]. Mutant KRAS is also known to reprogram the TME through the expression of HK1/2, phosphofructokinase 1, and LDHA, which are rate-limiting enzymes in glucose metabolism [14, 28–30]. Furthermore, KRAS/MAPK signaling upregulates MYC, resulting in increased expression of non-oxidative PPP gene, RPIA, which sustains elevated nucleotide biosynthesis [31]. Consistently, the lack of mutant KRAS expression results in a decrease in rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes levels and significant tumor regression [31]. Moreover, mutant KRAS mediates the reprogramming of non-canonical glutamine metabolism, which results in a cellular redox state that favors tumor growth [23]. Taken together, these studies support a key role for mutant KRAS in maintaining pancreatic tumor growth through the selective activation and adaptation of biosynthetic metabolic pathways (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Genetic alterations induce metabolic reprogramming in PDAC.

Mutant KRAS induces the transcription of Myc via the MAPK pathway increasing rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes, such as RPIA known to sustain nucleotide synthesis. In KRAS mutant tumors, p53 triggers the accumulation of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) and acts as a substrate for 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), which leads to chromatin modification resulting in increased cell differentiation and a decrease in cell fitness. Mutant KRAS can stimulate macropinocytosis and autophagy to recycle the necessary nucleotides, fatty acids, sugar, and amino acids required for cell turn over. KRAS mutations also provide near perfect conditions for cancer cells to thrive by elevating the levels of glucose and glycolytic intermediates, cellular redox potential, as well as fatty acids and glutamine uptake.

Cytokines-autophagy-metabolic reprogramming

Cytokines, chemokines, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are among the major inflammatory mediators. Cytokines are involved in numerous biological processes such as cellular metabolism, cell growth, and immune response and, depending on the cellular context, may have pro- or anti-inflammatory functions [3, 32]. An increased level of cytokines is reported in PDAC [3, 33, 34]. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL- 6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are classified as pro-inflammatory cytokines. IL-6-STAT3 signaling pathway plays a key role in promoting pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs) into PDAC and enhancing tumor cellular invasion [35, 36]. In addition, IL-1 promotes the development and progression of PDAC through activating oncogenic signaling pathways [37, 38]. Mutant KRAS and MYC inhibits the expression of type I interferon, which leads to the evasion of NK cells in PDAC [29]. Many of these cytokines are described as potential prognostic biomarkers showing an association with PDAC patient survival [3, 33, 34, 39].

The proinflammatory cytokine, Macrophage migration-inhibitory factor (MIF) [40] is highly expressed in PDAC. Patients with increased MIF levels in PDAC tumors have worse survival compared to patients with lower MIF expression. A novel MIF signaling pathway, involving MIF-miR-301b-NR3C2 axis, drives malignant disease progression in PDAC patients [41]. In line with the function of MIF in enhancing PDAC progression, exosomal MIF enhanced liver metastasis by forming a pre-metastatic niche in the liver through secretion of TGF-b and enhancing fibronectin production by hepatic stellate cells, resulting in a fibrotic microenvironment, which enhances recruitment of bone marrow-derived macrophages [42]. Taken together, these findings reveal an important role for cytokines in the growth and progression of PDAC.

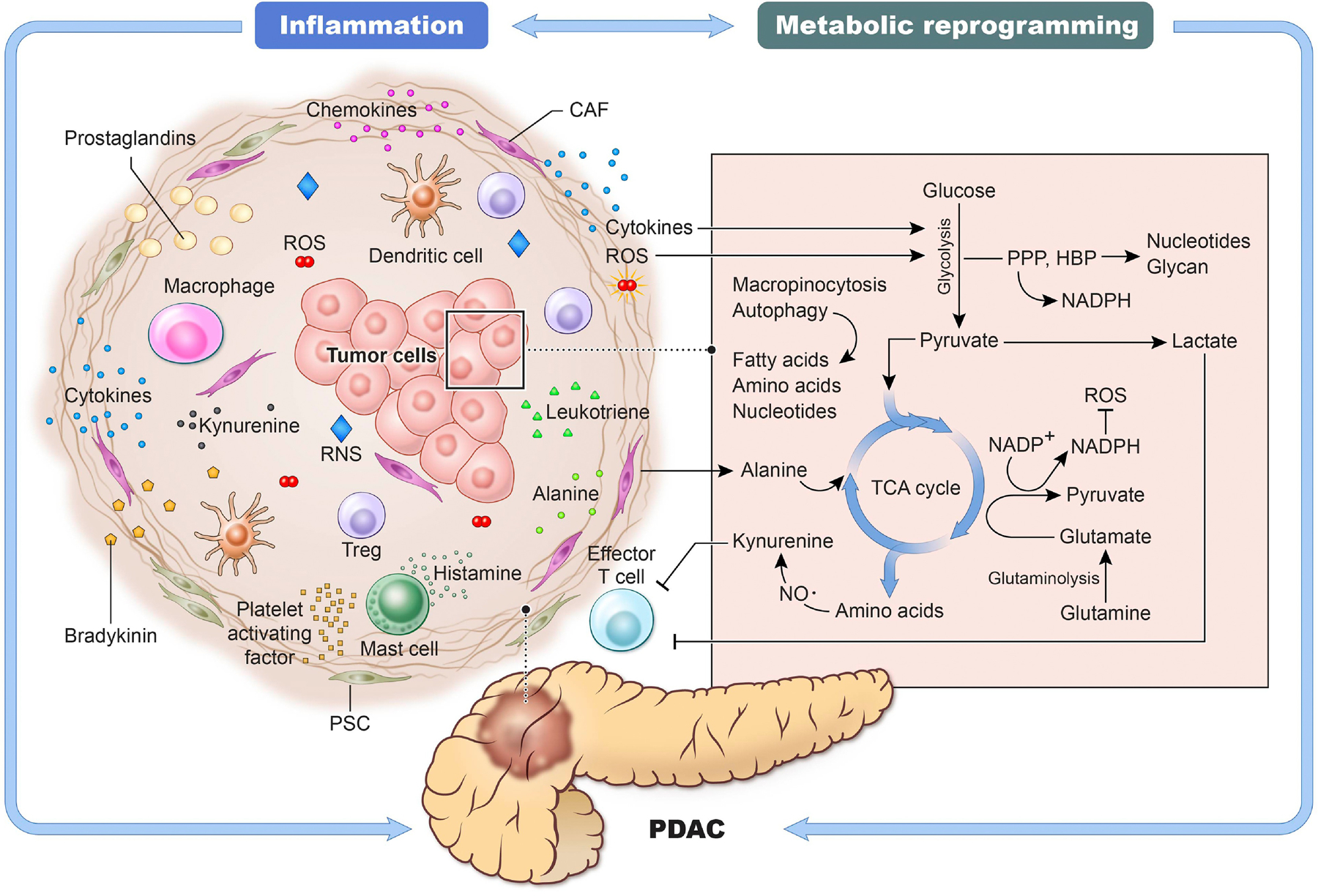

Autophagy is one of the major mechanisms for catabolizing intracellular biological molecules to support cellular homeostasis under stress. Autophagy is described as an important metabolic adaptation in PDAC for the survival and growth of tumor cells under a harsh, nutrient-scarce microenvironment [9, 43]. An interactive feedback mechanism has been described between inflammation and autophagy (Figure 3) [44–46]. Inflammatory mediators, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-6, TGF-β, and ROS, induce autophagy. In contrast, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-10 negatively regulate autophagy. Interestingly, autophagy inhibits cytokine production, including IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-18, and facilitates the production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and CXCL2. Previous studies have demonstrated an association between inflammatory mediators and autophagy in cancer. IL-6/STAT3-induced autophagy is required for the development and progression of PDAC [47]. Autophagy inhibition combined with MEK inhibition activates the STING/type I interferon pathway in PDAC cells, resulting in an enhanced antitumor immunity through activation of cytotoxic T cells in a mouse model [48]. Autophagy also promotes MHC-I degradation in PDAC leading to immune evasion, and inhibition of autophagy results in an enhanced anti-tumor immunity [49]. ROS have also been shown to augment autophagy. Human cancer cells bearing KRAS mutation show an increase in basal autophagy, which is required for preventing the accumulation of ROS, response to the increased metabolic and energy demand, and prevention of DNA damage [9, 14, 27, 28]. The inhibition of autophagy leads to increased ROS production, decreased mitochondrial OXPHOS, reduced glycolysis, and energy depletion, resulting in the suppression of PDAC growth [9, 14, 27, 28]. Inhibition of autophagy decreases PDAC growth in an autochthonous mouse model [50]. Moreover, IL-6 produced by PSCs induces autophagy in PDAC [51]. In addition, autophagy in stromal cells is critical for the metabolic crosstalk that fuels PDAC cells [50, 52]. Inflammatory mediators-autophagy-metabolic axis is an important signaling pathway, which contributes to the growth and progression of PDAC and may provide potentially useful targets and novel approaches to improve disease outcome.

Figure 3. Link between inflammatory mediators, autophagy, and metabolic reprogramming.

Cytokines work as either an inducer or an inhibitor of autophagy. Conversely, autophagy inhibits production of cytokines including IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-18 and also facilitates the production of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and CXCL2. Cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α and TGF-β, increase glucose uptake, glycolysis, and ROS scavenging pathway. Due to an increased demand of energy, cancer cells shift metabolism from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to anaerobic glycolysis. This shift can decrease mitochondrial metabolism accompanied by reduced ROS accumulation. ROS as an inflammatory mediator also regulates metabolism in cancer. ROS can induce glycolysis through stabilization of HIF-1α. Glycolysis, PPP, glutaminolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and one-carbon metabolism act as redox pathway to regulate ROS levels. PPP plays an important role in promoting cancer cell proliferation by increasing reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to scavenge ROS. NADPH is also generated through the non-canonical malate-aspartate shuttle to maintain redox balance in PDAC. The expression of aspartate transaminase (GOT1), which convers aspartate and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) into oxaloacetate (OAA) and glutamate, regulates this pathway. Elevated autophagy level in PDAC cells is required for protecting cells from ROS, responding to increased metabolic and energy demand, and preventing DNA damage, resulting in cancer cell survival.

Reactive oxygen species and metabolic reprogramming

ROS play important roles in cellular signaling. Elevated ROS production can cause cellular proliferation, increased metabolic activity, and DNA-damage that may promote mutagenesis [53]. In cancer cells, ROS levels are generally elevated and redox signaling pathways are activated. A higher level of ROS can be generated through various biological processes, including mitochondrial dysfunction and increased metabolic activity. The increased levels of ROS lead to PDAC progression [53]. In contrast, maintaining a proper level of intracellular ROS is important for cellular survival. One strategy that cancer cells utilize to overcome ROS toxicity and promote cellular growth is by reprogramming cellular metabolism [54]. In particular, glycolysis, PPP, glutaminolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and one-carbon metabolism act as redox pathways to regulate ROS levels [54] (Figure 3). PPP plays an important role in promoting cancer cell proliferation by increasing reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) to scavenge ROS as well as by supplying ribose-5-phosphate [54, 55]. TIGAR protein, which possesses antioxidant function, also regulates ROS and supports PanIN initiation while inhibiting metastasis in PDAC [56]. In addition, ROS induce HIF-1α, which can result in the induction of glycolysis [8] as HIF-1α regulates several genes involved in glucose metabolism. NADPH is also generated through the non-canonical malate-aspartate shuttle to maintain redox balance in PDAC [23, 57]. The expression of aspartate transaminase (GOT1), which converts aspartate and α-ketoglutarate into oxaloacetate and glutamate, regulates this pathway, and GOT1 is essential for PDAC growth.

Ferroptosis is a form of iron-dependent programmed cell death and is characterized by the accumulation of lipid ROS [58]. Cystine is imported into cytosol through a cysteine transporter, SLC7A11/xCT, to produce reduced glutathione (GSH) and this pathway is involved in ferroptosis. Recent studies showed that induction of ferroptosis in PDAC cells successfully suppressed PDAC growth [57, 59, 60]. CAFs in PDAC are highly dependent on SLC7A11 and the ablation of SLC7A11 increased ferroptosis in CAFs [61]. Although ROS promote tumorigenesis, a higher level of ROS may be toxic and inhibit tumor growth. Thus, both ROS production and redox signaling mechanism are well coordinated in cancer including PDAC to shift the balance of ROS towards tumorigenesis.

Cytokines and metabolic reprogramming

In addition to the metabolic reprogramming through autophagy, inflammatory mediators also contribute directly to cellular metabolic reprogramming [14, 62] (Figure 3). TNF-α and IL-17 cooperatively stimulate glycolysis through induction of the glucose transporter SLC2A1 and HK2 as well as the glycolysis regulators HIF-1α and MYC in colorectal cancers [14]. IL-6 upregulates the expression of glycolytic enzymes through activation of STAT3/c-myc signaling pathway in colorectal cancer [63]. Likewise, IL-22 secreted by CAFs activates PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway and regulates metabolic genes in non-small cell lung cancer [64]. In PDAC cells, KRAS-induced type I cytokine receptor complexes (IL2rγ-IL4rα and IL2rγ-IL13rα1) accelerate glycolysis through Jak1-Stat6-MYC pathway [30]. IL-6 and stromal-derived factor-1α secreted from CAFs induces purine nucleotide synthesis and ROS scavenging through Nrf2 signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer [65]. Additionally, TNF-α and TGF-β increase glucose uptake and lactate secretion in cancer, including PDAC [62, 66]. Furthermore, TGF-β stimulates PFKFB3 in glycolysis [67]. In this context, SARS-CoV-2-induced cytokines may affect tumorigenesis and metabolic reprogramming, including glycolysis and kynurenine signaling pathway, which is mediated by the SARS-Cov-2 induced cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-1, as reported in COVID-19 patients and mouse models [68–71]. Furthermore, nitric oxide-induced kynurenine signaling enhances disease aggressiveness in PDAC [72]. These pathways may offer potential targets with therapeutic significance.

Metabolic reprogramming in immune cells

The regulation of metabolic reprogramming in immune cells by inflammatory mediators and metabolites has been extensively studied and reported to induce immune suppression [25, 73]. T cells are key players in the host immune response to cancer. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are less dependent on glycolysis (and more OXPHOS dependent) and are also resistant to the specific TME (e.g., high lactate, low glucose, hypoxia, kynurenine, depletion of extracellular amino acids), while effector T cells and NK cells are dependent on glycolysis and are impaired by such microenvironment, resulting in immunosuppression [25, 73, 74]. Monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) are expressed in both stromal and cancer cells in various types of cancers [75]. MCTs are involved in metabolic signaling and metabolite exchange. Glycolytic cancer cells secrete lactate through MCT4/SLC16A3 into stroma. Tregs and CAFs enhance uptake and metabolism of lactate through upregulation of MCT1/SLC16A1 and LDH [76–78]. Effector T cells export lactate through MCT1. However, MCT1 activity is blocked by high lactate concentration in the TME, thereby preventing the discharge of lactate and disturbing cytotoxic T cell function [75]. Endothelial cells use MCT1 to import lactate released from tumor cells through MCT4, resulting in the activation of pro-angiogenic factors [75, 79]. Additionally, antitumor macrophages are dependent on glycolysis, whereas immunosuppressive macrophages are more dependent on OXPHOS [14, 25]. In addition, MDSCs and protumor macrophages enhance arginine metabolism. Increased glycolysis is also observed in B cells and dendritic cells. Furthermore, kynurenine level is enhanced in PDAC [72] and can suppress cytotoxicity of T cells [80]. The metabolic reprogramming induced by inflammatory mediators in cancer cells has not been adequately studied as compared to that in immune cells and, therefore, needs further investigation. Examining the effect of metabolites produced by tumor cells on stromal components would further elucidate the tumor stromal interaction and their role in pancreatic cancer progression.

Cancer Associated Fibroblasts and metabolic reprogramming

Collagen deposits in extracellular matrix are dense and rich in amino acids, such as proline and alanine, which contribute to the biomass demand of PDAC cells, thereby enabling tumor growth [81, 82]. Lipidome remodeling in CAFs [83] increases secretion of lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) by CAFs, which is hydrolyzed by autotaxin and supplies the necessary lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) for membrane synthesis in PDAC cells. Therefore, the LPC-autotaxin-LPA axis promotes PDAC progression. CAFs have been shown to aid in the enhanced metabolic need for tumor growth by providing alanine [52]. CAF-derived alanine is taken up by cancer cells and metabolized into pyruvate through transamination, which fuels the TCA cycle, supports lipids biosynthesis, and diverts glucose to produce serine and glycine. Cancer cells also induced autophagy in CAFs, resulting in alanine secretion by CAFs.

Several subtypes of CAFs have been described, such as inflammatory (iCAFs), myofibroblastic (myCAFs) and antigen-presenting (apCAFs) [15, 16, 84]. myCAFs express a lower level of IL-6. In contrast, iCAFs express a higher level of IL-6 [16]. Distinct from these two subtypes, apCAFs express MHC class II and CD74, but lack the costimulatory molecules required for T cell proliferation and is suggested to reduce anti-tumor immunity [15]. CAFs can also secrete cytokines and chemokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and leukemia inhibitory factor that supports PDAC tumorigenesis [17, 85]. Taken together, the role of CAFs in PDAC makes them an attractive target for developing novel therapeutic intervention strategies.

Inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming as target for intervention in PDAC

KRAS inhibitors have not been successful in the treatment of PDAC and other cancer types with mutant KRAS. To overcome this hurdle, the focus has shifted to downstream targets such as RAF, MEK, and ERK, but even targeting these pathways have not produced a significant response. Thus, studying the interactive roles of inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming may help identify novel molecular targets for PDAC patients with high prevalence of KRAS mutation (Figure 4). The inhibition of KRAS and its downstream target ERK/MAPK enhanced autophagy flux with attenuation of other KRAS- or ERK-mediated metabolic events, indicating an enhanced dependency of PDAC on autophagy [94]. Thus, autophagy can be one of the targets in a combinatorial therapeutic strategy. In this study, autophagy inhibition enhanced the antitumor activity of ERK inhibitors in KRAS-driven PDAC. Furthermore, the combined inhibition of autophagy and MEK1/2 synergistically inhibited PDAC. Consistently, the combined inhibition of autophagy and MEK1/2, attenuated the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells and growth of patient-derived PDAC tumor xenografts [95]. These findings indicate that inhibition of specific metabolic adaptation in combination with the targeting of KRAS downstream effectors may be a potentially useful strategy for clinical intervention.

Figure 4. Inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming as a target of PDAC.

Understanding the link between inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming may help design new and unique strategies to treat PDAC. Antibodies targeting the inflammatory mediators and inhibitors for cellular receptors can affect not only cancer cells but also the tumor microenvironment. Immune checkpoint receptors and inhibitors are also important in this context. Disconnecting PDAC cells and various cells in stroma by inhibitors of inflammatory mediators may help enhance chemotherapy/Immune checkpoint inhibitors. Although the levels of ROS may provide both pro-carcinogenic and anti-carcinogenic effects, achieving adequate ROS levels in cancer cells may be an interesting approach. Antioxidants can reduce the ROS-induced DNA damage, including gene mutations, while pro-oxidants may result in cancer cell death through inhibiting redox signaling. Various metabolic inhibitors are in ongoing clinical trials in a variety of cancers. Autophagy can be one of the targets because of its strong correlation with metabolic pathways, which are required for cell survival.

Preclinical studies have provided evidence for potential therapeutic significance of targeting inflammatory mediators and their receptors [20, 21, 36, 38, 65, 96]. Antibodies and pharmacological inhibitors against these targets can affect both PDAC tumor cells and TME. Immune checkpoint receptors and the immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are important in this context [96–99]. The effects of ICIs are limited due to a low tumor mutational burden and immunosuppressive TME in PDAC. Thus, disrupting PDAC tumor-stromal interactions by specific inhibitors of inflammatory mediators may help enhance the effect of chemotherapy/ICI [96, 97]. Clinical trials targeting inflammatory mediators have been designed [100]. COMBAT, a phase IIa clinical trial, was completed using the combination of the CXCR4 antagonist with pembrolizumab and chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic PDAC [101]. The survival was quite impressive for the patients that received the combination drugs. This synergistic effect was achieved by increased CD8+ effector T cell infiltration and decreased Tregs and MDSCs.

CXCR2 is another significant inflammatory pathway that is known to advance PDAC because of its ability to mobilize neutrophils out of the bone marrow and to the site of inflammation. Inhibition of CXCR2 signaling inhibited metastasis and improved T cell entry into the tumor in a KPC mouse model [102]. The combined inhibition of CXCR2 and PD-1 significantly prolonged survival in mice. Neutrophils and MDSCs play a key role in CXCR2-mediated establishment of the metastatic niche. Consistently, dual targeting of CXCR2+ neutrophils and CCR2+ macrophages improved antitumor immunity and chemotherapeutic response in PDAC [103].

ROS modulators (pro-oxidants and antioxidants) may potentially block tumor progression. However, the levels of ROS may have both pro-carcinogenic and anti-carcinogenic effects. Therefore, achieving optimal ROS levels in cancer cells may be an interesting and challenging strategy [56]. Various drugs known to interact with cellular metabolism can be used for cancer treatments and are undergoing clinical trials in a variety of cancers [104]. For PDAC, currently ascorbate is in clinical trial [105, 106]. Ascorbate depletes NAD+ and ATP through inducing ROS, which results in cell death. Metabolic inhibitors may also reduce therapeutic resistance by modulating the metabolism responsible for an anticancer-drug resistance phenotype [107]. The therapeutic effects of kynurenine-degrading enzymes have been shown in several cancer cell lines as a single agent or in combination with ICIs [108, 109]. Such agents may be applied to PDAC patients with high levels of kynurenine. Fatty acid synthase (FASN) is an enzyme responsible for FA synthesis and has currently been the choice of multiple ongoing clinical trials. It is important to note that an ongoing phase II clinical trial for a FASN inhibitor (TVB-2640) is currently active for use in metastatic or advanced KRAS mutant non-small cell lung cancers [110]. This could be an interesting additional combination for current PDAC therapies since KRAS mutations are found in over 95% of these tumors. Further molecular insights into the interactive roles of inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming may be helpful in the development of novel targets and drug repositioning in this field.

Concluding Remarks

The link between inflammatory mediators, autophagy, molecular subtype (Box 1), and metabolic reprogramming is highly complex (Figure 5, Key Figure) but critically important and, therefore, needs extensive elucidation. The interactive and coordinated feedback loops regulating the two cancer hallmarks, inflammation and metabolic reprogramming, in pancreatic cancer offer opportunities to understand the underlying mechanisms of disease progression and therapeutic resistance, which may be exploited for developing novel therapeutic strategies (See Outstanding questions).

Box 1. Molecular subtype and metabolic reprogramming.

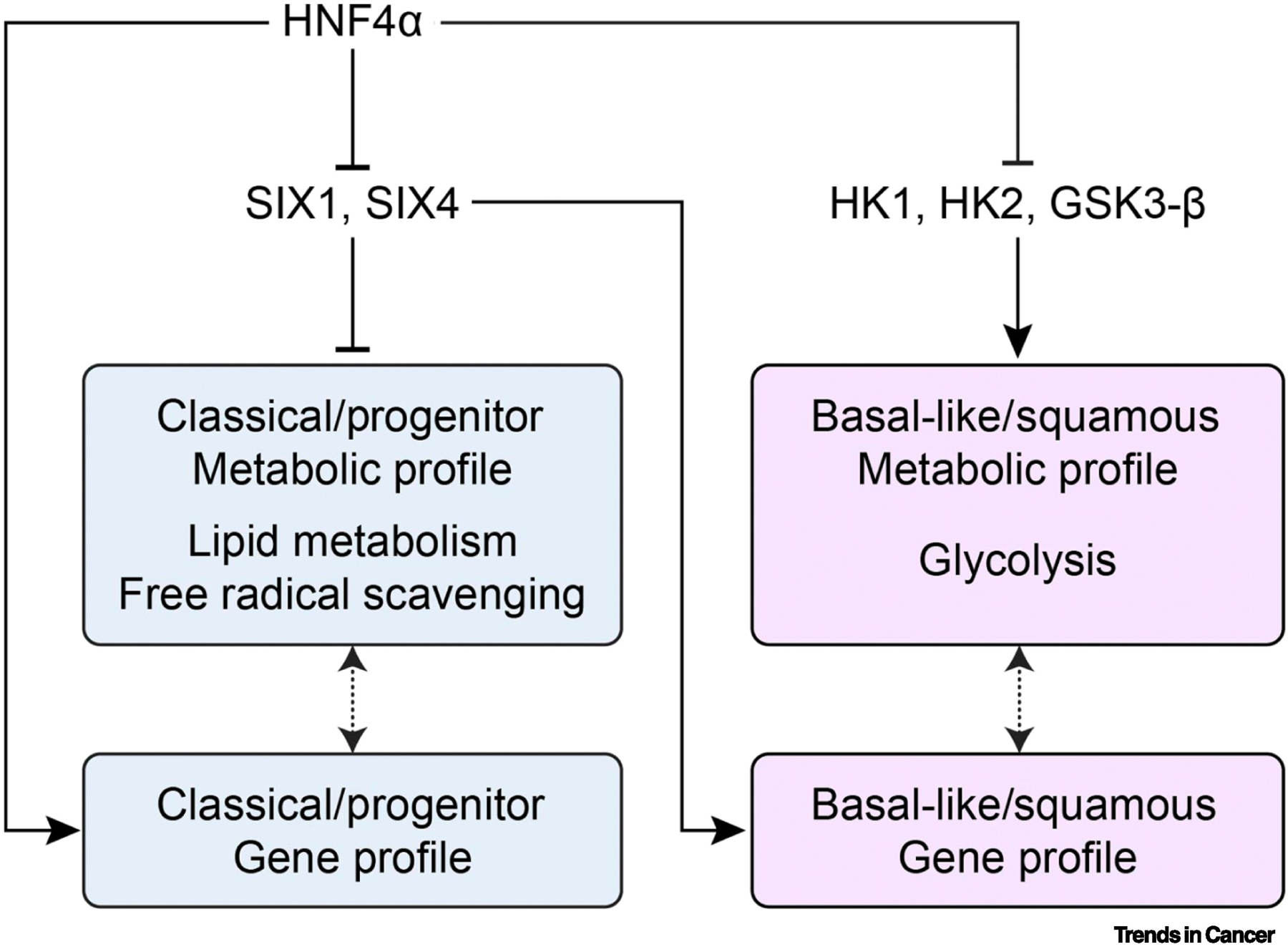

Several molecular subtypes of PDAC with distinct prognosis have been described [86, 87]. PDAC can be classified into four subtypes: squamous, pancreatic progenitor, immunogenic, and aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine [86]. Patients with the squamous subtype have the worst prognosis and this subtype reveals distinct features related to inflammation, metabolic reprogramming, autophagy, hypoxia, TGF-β signaling, and activated MYC pathways. Conversely, the immunogenic subtype shows enrichment in the expression of genes associated with different immune cell types. Recently, it has been proposed that PDAC be broadly classified into two subtypes; basal-like/squamous and classical/progenitor [88].

Molecular subtypes of PDAC have distinct metabolic profiles [89–91]. Basal-like/squamous subtype shows an increase in glycolysis, while classical/progenitor subtype has enhanced lipogenic pathways. Employing subtype specific gene signature [87], HNF4α was observed to induce the classical subtype and enrichment of lipid metabolism and free radical scavenging through attenuation of SIX4 and SIX1, which favors basal-like subtype in PDAC cells [92]. In contrast, another study revealed that loss of HNF4α accelerated a squamous-like metabolic profile (glycolysis) through upregulating HK1 and HK2, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β) [93]. (Figure I). Therefore, it is conceivable that specific metabolic inhibitors for each tumor subtype may help in guiding precision medicine strategies.

Figure I. Box 1. Molecular subtypes and metabolic reprogramming in PDAC.

Classical/progenitor subtype enhances lipogenic and redox pathway, while basal-like/squamous subtype shows enhanced glycolysis. HNF4α induces the classical/progenitor subtype through inhibiting SIX1, SIX4, and glycolytic enzymes. Loss of HNF4α accelerates a squamous-like metabolic profile (glycolysis) through upregulating HK1 and HK2, and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK-3β).

Figure 5, Key Figure. Link between inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming in PDAC.

Chronic inflammation is an important event in PDAC. The tumor microenvironment is remodeled by several inflammatory mediators secreted by immune cells as well as cancer cells creating favorable conditions for tumor cells to thrive. Cytokines and ROS may support cell growth through glycolysis and autophagy. Lactate produced by glycolysis inhibits anti-cancer immunity. At the same time, cancer cells can produce kynurenine, which reduces the functional ability of cytotoxic T cells. The synthesis and turnover of cellular components such as amino acids, nucleotides, and fatty acids are supported by several pathways, including TCA cycle, macropinocytosis, and autophagy. CAFs are responsible for the production of amino acid-rich collagen containing alanine and proline, meeting the demands for cancer cell biomass. NADPH produced by glycolytic intermediates and TCA cycle plays an antioxidant role by reducing ROS. These inter-regulatory signaling between inflammation and metabolic reprogramming play critical roles in the growth and progression of pancreatic cancer.

Outstanding Questions Box 1.

The link between inflammatory mediators and metabolic reprogramming and their interactions in tumor cells are not adequately studied. How do inflammatory mediators regulate metabolism in PDAC tumors?

Link between inflammatory mediators and autophagy is described in cancer, however, a comprehensive elucidation is lacking in PDAC. How does inflammatory signaling regulate autophagy in PDAC? and what are the molecular mechanisms which regulate the dual role of autophagy in the progression of PDAC?

How do PDAC tumor cells-derived metabolites contribute to tumor-stromal interactions?

Although previous studies have shown that basal-like/squamous and classical/progenitor subtype associated with glycolytic intermediates/amino acid synthesis and lipogenesis, respectively, what are the mechanistic and functional roles of gene-signatures, associated with these subtypes, in regulating metabolic profiles (Figure 4, dotted arrows)?

KRAS is an attractive therapeutic target but, so far, with no promising outcome. What are the key potential targets linking inflammation and metabolic reprogramming which could be pursued in PDAC?

Which metabolic dependency is the key driver in PDAC?

Can we effectively target inflammatory mediators in combination with immunotherapy to inhibit PDAC progression? Can multiple targets of inflammation and metabolic pathways be combined to obtain a more effective response?

How does chemotherapy/immune checkpoint inhibitors affect metabolic reprogramming in PDAC?

Highlights.

Inflammation and metabolic reprogramming play critical roles in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer by inducing and/or regulating key tumorigenic events.

KRAS mutation, inflammatory mediators, and autophagy induce metabolic reprogramming such as rewiring of glycolytic pathways, salvaging nutrients, and regulation of redox status for survival and growth of malignant cells under harsh tumor microenvironment.

Aggressive basal-like/squamous molecular subtype of pancreatic cancer utilizes glycolytic intermediates and amino acids effectively, whereas classical/progenitor subtype accelerates lipogenic pathways.

Understanding the circuitry of inter-regulatory role of inflammatory pathways and metabolic reprogramming in pancreatic cancer potentially provides opportunities to improve the effectiveness of existing treatment regimens as well as identify novel targets in designing potentially effective strategies for clinical intervention.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the intramural research program of Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, NIH. Authors would like to thank Helen Cawley for critical reading of the manuscript and providing the editorial assistance.

Abbreviations:

- αSMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- FASN

Fatty acid synthase

- GEMM

Genetically engineered mouse model

- IL

Interleukin

- MDSCs

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MIF

Migration-inhibitory factor

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NADPH

Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PanINs

Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias

- PSCs

Pancreatic stellate cells

- PPP

Pentose phosphate pathway

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Tregs

Regulatory T cells

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- TGF-β

Tumor growth factor-β

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor α

Glossary

- Autophagy

Cell degradation process necessary for cellular turnover. Removes and replaces damaged cellular components, which is then utilized to prevent accumulation of abnormal protein or to recycle protein in nutrient starved conditions for preserving cell homeostasis.

- Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

originating from pancreatic stellate cells, CAFs are responsible for collagen deposits in desmoplasia, recruitment of inflammatory/immune cells into tumor microenvironment, and plays multiple roles in tumor microenvironment supporting tumor growth and progression. CAFs possess unique characteristics as compared with normal fibroblasts but maintain a myofibroblastic phenotype such as the expression of α-smooth muscle actin, which plays a role in permanent tissue contraction.

- Desmoplasia

A highly reactive massive stroma, which is a well-established characteristic of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. It is made up of collagens, fibronectin, fibroblasts and is maintained by pancreatic stellate cells. Desmoplastic stroma may act as a barrier for chemotherapeutics and encourage tumor cell growth. However, it may also restrain tumor cells and inhibit migration to distant organs.

- Ferroptosis

a form of programmed cell death dependent on iron and characterized by the accumulation of lipid ROS, which is caused by the imbalance between the levels of oxidative damages and glutathione-dependent antioxidant defenses

- Glycolysis

metabolic pathway that breaks down glucose into pyruvate under aerobic conditions and lactate in anaerobic conditions.

- Hypoxia

Oxygen-deprived tumor microenvironment.

- Inflammatory mediators

signaling molecules released by cells of the immune system that contribute to inflammation. Some examples include cytokines, chemokines, complements, histamine, bradykinin, serotonin, prostaglandin, leukotriene, platelet-activating factor, and reactive oxygen species.

- Macrophage migration-inhibitory factor (MIF)

a pro-inflammatory cytokine that regulates immunity and inflammation. MIF is secreted by several cell types, including immune cells, cancer cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. MIF induces the expression of cytokines such as interleukin-1 and interleukin-6.

- Metabolic reprogramming

considered one of the hallmarks of cancer, this process consists of key metabolic adaptations supporting tumor growth and progression.

- Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

Heterogeneous group of immune cells that are derived from myeloid lineage and plays a role in inhibiting anti-tumor immunity.

- Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS)

Metabolic pathway for ATP synthesis which occurs in the inner mitochondrial membrane and requires oxygen.

- Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs)

Activated myofibroblasts that secrete and synthesize extracellular matrix components consisting of more than half of the tumor stroma. They can differentiate into different CAF populations and contribute to the aggressive nature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

- Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanINs)

pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia is a non-invasive precursor lesion that may develop into pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

- Pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)

a pathway that metabolizes glucose-6-phosphate into glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, which provides biomolecules including deoxyribose, ribose, and pentose. PPP may involve oxidative and/or nonoxidative pathways.

- Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Highly reactive molecules/irons/radicals derived from oxygen and are products of oxygen metabolism. Depending on the levels and cellular context, they may have either pro- or anti-tumorigenic functions.

- Tumor microenvironment (TME)

Immediate surrounding of tumor tissue in which tumor cells are embedded. It consists of a variety of cells including immune and inflammatory cells, inflammatory mediators, extracellular matrix, blood vessels, which may have multiple effects on tumor progression.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

None

References

- 1.Sung H et al. (2021) Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71 (3), 209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D and Weinberg Robert A. (2011) Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 144 (5), 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padoan A et al. (2019) Inflammation and Pancreatic Cancer: Focus on Metabolism, Cytokines, and Immunity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gukovsky I et al. (2013) Inflammation, Autophagy, and Obesity: Common Features in the Pathogenesis of Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 144 (6), 1199–1209.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rawla P et al. (2019) Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors. World journal of oncology 10 (1), 10–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buscail L et al. (2020) Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 17 (3), 153–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Poggetto E et al. (2021) Epithelial memory of inflammation limits tissue damage while promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis. Science 373 (6561), eabj0486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cairns RA et al. (2011) Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer 11 (2), 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Encarnación-Rosado J and Kimmelman AC (2021) Harnessing metabolic dependencies in pancreatic cancers. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 18 (7), 482–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu J et al. (2015) The Warburg effect in tumor progression: Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism. Cancer Letters 356 (2, Part A), 156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward Patrick S. and Thompson Craig B. (2012) Metabolic Reprogramming: A Cancer Hallmark Even Warburg Did Not Anticipate. Cancer Cell 21 (3), 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroemer G and Pouyssegur J (2008) Tumor Cell Metabolism: Cancer’s Achilles’ Heel. Cancer Cell 13 (6), 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao W et al. (2020) Recent insights into the biology of pancreatic cancer. EBioMedicine 53, 102655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dey P et al. (2021) Metabolic Codependencies in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discovery 11 (5), 1067–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biffi G et al. (2019) IL1-Induced JAK/STAT Signaling Is Antagonized by TGFbeta to Shape CAF Heterogeneity in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov 9 (2), 282–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Öhlund D et al. (2017) Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 214 (3), 579–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao W et al. (2018) Galectin-3 Mediates Tumor Cell–Stroma Interactions by Activating Pancreatic Stellate Cells to Produce Cytokines via Integrin Signaling. Gastroenterology 154 (5), 1524–1537.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizutani Y et al. (2019) Meflin-Positive Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Inhibit Pancreatic Carcinogenesis. Cancer Research 79 (20), 5367–5381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piersma B et al. (2020) Fibrosis and cancer: A strained relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1873 (2), 188356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rupert JE et al. (2021) Tumor-derived IL-6 and trans-signaling among tumor, fat, and muscle mediate pancreatic cancer cachexia. Journal of Experimental Medicine 218 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JW et al. (2019) Hepatocytes direct the formation of a pro-metastatic niche in the liver. Nature 567 (7747), 249–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banh RS et al. (2020) Neurons Release Serine to Support mRNA Translation in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell 183 (5), 1202–1218.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son J et al. (2013) Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS-regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 496 (7443), 101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galenkamp KMO et al. (2020) Golgi Acidification by NHE7 Regulates Cytosolic pH Homeostasis in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer discovery 10 (6), 822–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biswas Subhra K. (2015) Metabolic Reprogramming of Immune Cells in Cancer Progression. Immunity 43 (3), 435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halbrook CJ et al. (2019) Macrophage-Released Pyrimidines Inhibit Gemcitabine Therapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Metab 29 (6), 1390–1399.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerk SA et al. (2021) Metabolic networks in mutant KRAS-driven tumours: tissue specificities and the microenvironment. Nature Reviews Cancer 21 (8), 510–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant KL et al. (2014) KRAS: feeding pancreatic cancer proliferation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences 39 (2), 91–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthalagu N et al. (2020) Repression of the Type I Interferon Pathway Underlies MYC- and KRAS-Dependent Evasion of NK and B Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discovery 10 (6), 872–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dey P et al. (2020) Oncogenic KRAS-Driven Metabolic Reprogramming in Pancreatic Cancer Cells Utilizes Cytokines from the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discovery 10 (4), 608–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santana-Codina N et al. (2018) Oncogenic KRAS supports pancreatic cancer through regulation of nucleotide synthesis. Nat Commun 9 (1), 4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coussens LM and Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420 (6917), 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babic A et al. (2018) Plasma inflammatory cytokines and survival of pancreatic cancer patients. Clinical and translational gastroenterology 9 (4), 145–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dima SO et al. (2012) An exploratory study of inflammatory cytokines as prognostic biomarkers in patients with ductal pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 41 (7), 1001–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Ismaeel Q et al. (2019) ZEB1 and IL-6/11-STAT3 signalling cooperate to define invasive potential of pancreatic cancer cells via differential regulation of the expression of S100 proteins. British Journal of Cancer 121 (1), 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nagathihalli NS et al. (2016) Pancreatic stellate cell secreted IL-6 stimulates STAT3 dependent invasiveness of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer cells. Oncotarget 7 (40), 65982–65992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mantovani A et al. (2019) Interleukin-1 and Related Cytokines in the Regulation of Inflammation and Immunity. Immunity 50 (4), 778–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhuang Z et al. (2016) IL1 Receptor Antagonist Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer Growth by Abrogating NF-κB Activation. Clinical Cancer Research 22 (6), 1432–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lesina M et al. (2011) Stat3/Socs3 Activation by IL-6 Transsignaling Promotes Progression of Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Development of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 19 (4), 456–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lippitz BE (2013) Cytokine patterns in patients with cancer: a systematic review. The Lancet Oncology 14 (6), e218–e228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang S et al. (2016) A Novel MIF Signaling Pathway Drives the Malignant Character of Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting NR3C2. Cancer Research 76 (13), 3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa-Silva B et al. (2015) Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nature Cell Biology 17 (6), 816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kimmelman AC and White E (2017) Autophagy and Tumor Metabolism. Cell Metabolism 25 (5), 1037–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harris J (2011) Autophagy and cytokines. Cytokine 56 (2), 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ge Y et al. (2018) Autophagy and proinflammatory cytokines: Interactions and clinical implications. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 43, 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian M et al. (2017) Autophagy and inflammation. Clinical and Translational Medicine 6 (1), 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang R et al. (2012) The expression of the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) is permissive for early pancreatic neoplasia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (18), 7031–7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang H et al. (2022) Activating Immune Recognition in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma via Autophagy Inhibition, MEK Blockade, and CD40 Agonism. Gastroenterology 162 (2), 590–603.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamamoto K et al. (2020) Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I. Nature 581 (7806), 100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang A et al. (2018) Autophagy Sustains Pancreatic Cancer Growth through Both Cell-Autonomous and Nonautonomous Mechanisms. Cancer Discov 8 (3), 276–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Endo S et al. (2017) Autophagy Is Required for Activation of Pancreatic Stellate Cells, Associated With Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Promotes Growth of Pancreatic Tumors in Mice. Gastroenterology 152 (6), 1492–1506.e24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sousa CM et al. (2016) Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 536 (7617), 479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liou G-Y and Storz P (2010) Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free radical research 44 (5), 479–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Panieri E and Santoro MM (2016) ROS homeostasis and metabolism: a dangerous liason in cancer cells. Cell Death & Disease 7 (6), e2253–e2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sousa CM and Kimmelman AC (2014) The complex landscape of pancreatic cancer metabolism. Carcinogenesis 35 (7), 1441–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheung EC et al. (2020) Dynamic ROS Control by TIGAR Regulates the Initiation and Progression of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 37 (2), 168–182.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kremer DM et al. (2021) GOT1 inhibition promotes pancreatic cancer cell death by ferroptosis. Nature Communications 12 (1), 4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stockwell BR et al. (2017) Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 171 (2), 273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Badgley MA et al. (2020) Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice. Science (New York, N.Y.) 368 (6486), 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li C et al. (2021) Mitochondrial DNA stress triggers autophagy-dependent ferroptotic death. Autophagy 17 (4), 948–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharbeen G et al. (2021) Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Determine Response to SLC7A11 Inhibition. Cancer Research 81 (13), 3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hua W et al. (2020) TGFβ-induced metabolic reprogramming during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 77 (11), 2103–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Qu D et al. (2017) Chronic inflammation confers to the metabolic reprogramming associated with tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Biology & Therapy 18 (4), 237–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H et al. (2019) Interleukin-22 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts regulates the proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer cells via the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway. American journal of translational research 11 (7), 4077–4088. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu YS et al. (2016) Soluble factors from stellate cells induce pancreatic cancer cell proliferation via Nrf2-activated metabolic reprogramming and ROS detoxification. Oncotarget 7 (24), 36719–36732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu M et al. (2016) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induction is associated with augmented glucose uptake and lactate production in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer & Metabolism 4 (1), 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yalcin A et al. (2017) 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose 2,6-bisphosphatase-3 is required for transforming growth factor β1-enhanced invasion of Panc1 cells in vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 484 (3), 687–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thomas T et al. (2020) COVID-19 infection alters kynurenine and fatty acid metabolism, correlating with IL-6 levels and renal status. JCI insight 5 (14), e140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li S et al. (2021) Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic changes of vital organs in SARS-CoV-2-induced systemic toxicity. JCI insight 6 (2), e145027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Codo AC et al. (2020) Elevated Glucose Levels Favor SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Monocyte Response through a HIF-1α/Glycolysis-Dependent Axis. Cell Metabolism 32 (3), 437–446.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiao N et al. (2021) Integrated cytokine and metabolite analysis reveals immunometabolic reprogramming in COVID-19 patients with therapeutic implications. Nature Communications 12 (1), 1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L et al. (2020) NO•/RUNX3/kynurenine metabolic signaling enhances disease aggressiveness in pancreatic cancer. International Journal of Cancer 146 (11), 3160–3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pearce Erika L. and Pearce Edward J. (2013) Metabolic Pathways in Immune Cell Activation and Quiescence. Immunity 38 (4), 633–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brand A et al. (2016) LDHA-Associated Lactic Acid Production Blunts Tumor Immunosurveillance by T and NK Cells. Cell Metabolism 24 (5), 657–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Payen VL et al. (2020) Monocarboxylate transporters in cancer. Molecular Metabolism 33, 48–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watson MJ et al. (2021) Metabolic support of tumour-infiltrating regulatory T cells by lactic acid. Nature 591 (7851), 645–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mishra D and Banerjee D (2019) Lactate Dehydrogenases as Metabolic Links between Tumor and Stroma in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 11 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kumagai S et al. (2022) Lactic acid promotes PD-1 expression in regulatory T cells in highly glycolytic tumor microenvironments. Cancer Cell [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Végran F et al. (2011) Lactate Influx through the Endothelial Cell Monocarboxylate Transporter MCT1 Supports an NF-κB/IL-8 Pathway that Drives Tumor Angiogenesis. Cancer Research 71 (7), 2550–2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jonescheit H et al. (2020) Influence of Indoleamine-2,3-Dioxygenase and Its Metabolite Kynurenine on γδ T Cell Cytotoxicity against Ductal Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Cells. Cells 9 (5), 1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Helms E et al. (2020) Fibroblast Heterogeneity in the Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Discov 10 (5), 648–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Olivares O et al. (2017) Collagen-derived proline promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell survival under nutrient limited conditions. Nature Communications 8 (1), 16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Auciello FR et al. (2019) A Stromal Lysolipid–Autotaxin Signaling Axis Promotes Pancreatic Tumor Progression. Cancer Discovery 9 (5), 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elyada E et al. (2019) Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Antigen-Presenting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discov 9 (8), 1102–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shi Y et al. (2019) Targeting LIF-mediated paracrine interaction for pancreatic cancer therapy and monitoring. Nature 569 (7754), 131–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bailey P et al. (2016) Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature 531 (7592), 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moffitt RA et al. (2015) Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma- specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nature Genetics 47 (10), 1168–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.(2017) Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 32 (2), 185–203.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Espiau-Romera P et al. (2020) Molecular and Metabolic Subtypes Correspondence for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Classification. J Clin Med 9 (12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mehla K and Singh PK (2020) Metabolic Subtyping for Novel Personalized Therapies Against Pancreatic Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 26 (1), 6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Daemen A et al. (2015) Metabolite profiling stratifies pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas into subtypes with distinct sensitivities to metabolic inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112 (32), E4410–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Camolotto SA et al. (2021) Reciprocal regulation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma growth and molecular subtype by HNF4α and SIX1/4. Gut 70 (5), 900–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brunton H et al. (2020) HNF4A and GATA6 Loss Reveals Therapeutically Actionable Subtypes in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Reports 31 (6), 107625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bryant KL et al. (2019) Combination of ERK and autophagy inhibition as a treatment approach for pancreatic cancer. Nature Medicine 25 (4), 628–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kinsey CG et al. (2019) Protective autophagy elicited by RAF→MEK→ERK inhibition suggests a treatment strategy for RAS-driven cancers. Nature Medicine 25 (4), 620–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mace TA et al. (2018) IL-6 and PD-L1 antibody blockade combination therapy reduces tumour progression in murine models of pancreatic cancer. Gut 67 (2), 320–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lu S-W et al. (2020) IL-20 antagonist suppresses PD-L1 expression and prolongs survival in pancreatic cancer models. Nature Communications 11 (1), 4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bian J and Almhanna K (2021) Pancreatic cancer and immune checkpoint inhibitors-still a long way to go. Translational gastroenterology and hepatology 6, 6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Henriksen A et al. (2019) Checkpoint inhibitors in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 78, 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Berraondo P et al. (2019) Cytokines in clinical cancer immunotherapy. British Journal of Cancer 120 (1), 6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bockorny B et al. (2020) BL-8040, a CXCR4 antagonist, in combination with pembrolizumab and chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer: the COMBAT trial. Nat Med 26 (6), 878–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Steele CW et al. (2016) CXCR2 Inhibition Profoundly Suppresses Metastases and Augments Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 29 (6), 832–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nywening TM et al. (2018) Targeting both tumour-associated CXCR2(+) neutrophils and CCR2(+) macrophages disrupts myeloid recruitment and improves chemotherapeutic responses in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gut 67 (6), 1112–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Luengo A et al. (2017) Targeting Metabolism for Cancer Therapy. Cell chemical biology 24 (9), 1161–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Polireddy K et al. (2017) High Dose Parenteral Ascorbate Inhibited Pancreatic Cancer Growth and Metastasis: Mechanisms and a Phase I/IIa study. Scientific Reports 7 (1), 17188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Alexander MS et al. (2018) Pharmacologic Ascorbate Reduces Radiation-Induced Normal Tissue Toxicity and Enhances Tumor Radiosensitization in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Research 78 (24), 6838–6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pranzini E et al. (2021) Metabolic Reprogramming in Anticancer Drug Resistance: A Focus on Amino Acids. Trends in Cancer [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Labadie BW et al. (2019) Reimagining IDO Pathway Inhibition in Cancer Immunotherapy via Downstream Focus on the Tryptophan–Kynurenine–Aryl Hydrocarbon Axis. Clinical Cancer Research 25 (5), 1462–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Triplett TA et al. (2018) Reversal of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase–mediated cancer immune suppression by systemic kynurenine depletion with a therapeutic enzyme. Nature Biotechnology 36 (8), 758–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Falchook G et al. (2021) First-in-human study of the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of first-in-class fatty acid synthase inhibitor TVB-2640 alone and with a taxane in advanced tumors. EClinicalMedicine 34, 100797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]