Abstract

The development of supramolecular hosts with effective host–guest properties is crucial for their applications. Herein, we report the preparation of a porphyrin-based metallacage, which serves as a host for a series of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The association constant between the metallacage and coronene reaches 2.37 × 107 M–1 in acetonitrile/chloroform (ν/ν = 9/1), which is among the highest values in metallacage-based host–guest complexes. Moreover, the metallacage exhibits good singlet oxygen generation capacity, which can be further used to oxidize encapsulated anthracene derivatives into anthracene endoperoxides, leading to the release of guests. By employing 10-phenyl-9-(2-phenylethynyl)anthracene whose endoperoxide can be converted back by heating as the guest, a reversible controlled release system is constructed. This study not only gives a type of porphyrin-based metallacage that shows desired host–guest interactions with PAHs but also offers a photooxidation-responsive host–guest recognition motif, which will guide future design and applications of metallacages for stimuli-responsive materials.

Keywords: multicomponent metallacages, porphyrin, host−guest complexation, photooxidation, reversible encapsulation and release

Introduction

The design and preparation of supramolecular hosts, which can effectively encapsulate guest molecules remain a central theme of supramolecular chemistry.1,2 Such host–guest systems possess good selectivity, high efficiency, and stimuli responsiveness, enabling their wide applications in the construction of advanced supramolecular materials.3,4 So far, numerous host systems have been developed including, but not limited to, crown ethers,5−7 cyclodextrins,8,9 calixarenes,10,11 cucurbiturils,12,13 cyclophanes,14,15 and pillararenes16,17 for a wide array of applications in sensing,18,19 separation and purification,20,21 transportation,22,23 drug delivery and release,24,25 etc. These covalent hosts possess enhanced stabilities, which enable them to be ideal building blocks for the preparation of robust materials. Their functionalization, however, is generally tedious and time-consuming and sometimes quite challenging, especially for water-soluble hosts such as cucurbiturils.26,27 Directional self-assembly is emerging as an alternative approach for providing noncovalently linked supramolecular hosts with tunable and adjustable cavities.28,29 Moreover, further functionalities can be readily introduced into the noncovalent hosts via the selection and modification of building blocks toward advanced applications.30,31

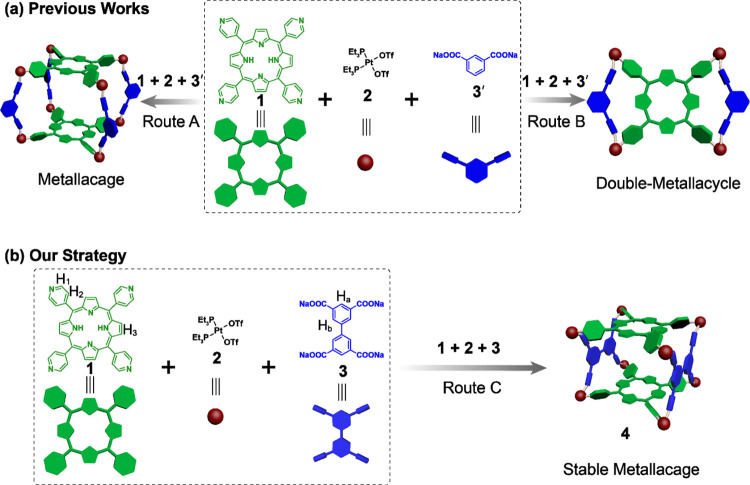

Owing to their moderate bond strength and well-defined directionality, metal-coordination interactions have proved to be ideal noncovalent interactions for assembling metallacycles32−36 and metallacages,37−44 which are further employed as supramolecular hosts with predictable shapes and sizes. Compared with two-dimensional metallacycles, metallacages possess three-dimensional structures and cavities, making them encapsulate guest molecules from multiple directions and thus offering host–guest complexes with high binding affinities.45,46 Therefore, during the past three decades, various metallacages have been extensively investigated and applied for guest encapsulation,47−49 catalysis,50−53 stabilizing reactive intermediates,54,55 etc. Among them, porphyrin-based metallacages56,57 have received much attention because they integrate the interesting optical and redox abilities of porphyrins and the host–guest properties of metallacages, offering extra functionalization such as light-harvesting and biological catalysis.58−62 As an important branch of porphyrin-based metallacages, multicomponents have also been widely explored.63−65 However, although these papers proposed that they had the metallacages, no crystal structures were provided. In a very recent study,66 different from previously reported three-dimensional (3D) prisms (Figure 1, route A), the self-assembly from tetrapyridyl porphyrin (1), Pt(PEt3)2(OTf)2 (2), and dicarboxylate ligands (3′) was found to afford two-dimensional (2D) Bow Ties (Figure 1, route B) instead of 3D prisms, based on the X-ray crystal structures and detailed nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis. This finding casted a shadow on the future study of porphyrin-based multicomponent metallacages. Therefore, the exploration of multicomponent self-assembly to generate metallacages rather than metallacycles is urgently needed.

Figure 1.

Different strategies for the self-assembly from tetrapyridyl porphyrin 1, cis-Pt(PEt3)2(OTf)22, and multicarboxylate ligands 3 or 3′.

Herein, we use tetracarboxylate ligands (3) instead of dicarboxylate ligands (3′) as the carboxylic building blocks and prepare a porphyrin-based metallacage (4) via multicomponent self-assembly (Figure 1, route C). This strategy excludes the formation of 2D metallacycle structures and offers improved stability for the metallacage via multiple cooperative N–Pt–O coordination bonds. Moreover, the metallacage possesses a box-shaped structure with openings at both ends, which can allow easy access for planar organic molecules. The two π-conjugated, electron-rich porphyrin faces are aligned parallel to encapsulate planar molecules through π–π stacking. Therefore, the host–guest chemistry of the porphyrin-based metallacage was further systematically studied using polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as the guests.67−71 It is worth mentioning that the crystal structures of all of the host–guest complexes are well resolved. More interestingly, the metallacage can generate singlet oxygen (1O2) effectively upon photoirradiation, which will weaken the host–guest interactions and trigger the release of anthracene-derived guests via photooxidation. By further heating the system, the released endoperoxide guest, viz., 10-phenyl-9-(2-phenylethynyl)anthracene, can be converted back and reencapsulated. Such a host–guest system with photoresponsive encapsulation and release capability is constructed and may find further applications as stimuli-responsive materials.

Results and Discussion

Preparation and Characterization Studies of Metallacages

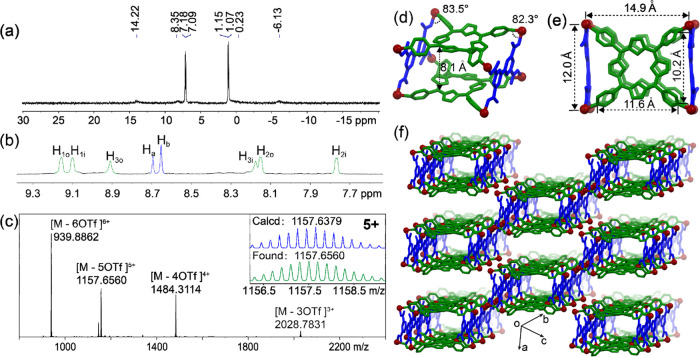

Based on the self-assembly of tetrapyridyl porphyrin (1), tetracarboxylic ligand (2), and cis-Pt(PEt3)2(OTf)2 (3), metallacage 4 was successfully prepared. The structure of the metallacage was fully characterized by multinuclear NMR (31P{1H} and 1H), electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS), and X-ray diffraction analysis. The 31P{1H} NMR spectra of 4 split into two doublet peaks at 7.14 and 1.11 ppm (Figure 2a), which hold equal intensities with concomitant 195Pt satellites due to different phosphorus environments after the coordination of platinum atoms with pyridyl and carboxylic groups. In the 1H NMR spectra (Figure 2b), diagnostic chemical shift changes were observed for the porphyrinic protons H1, H2, and H3 and all of them split into two sets of signals after coordination, corresponding to the protons inside and outside of the metallacage. ESI-TOF-MS provided further evidence of the formation of the metallacage (Figure 2c). Peaks at m/z 939.8862, 1157.6560, 1484.3114, and 2028.7831 were found with isotopically well-resolved patterns, corresponding to [4 – 6OTf]6+, [4 – 5OTf]5+, [4 – 4OTf]4+, and [4 – 3OTf]3+.

Figure 2.

(a) Cartoon representations of metallacage 4 by multicomponent self-assembly; partial (b) 31P {1H} and (c) 1H NMR spectra (243 or 600 MHz, CD3CN, 295 K) of metallacage 4; (d) ESI-TOF-MS spectra of metallacage 4. (d–f) Crystal structure of metallacage 4. Hydrogen atoms, triethylphosphine units, counterions, and solvent molecules were omitted for clarity.72

Single crystals of 4 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained by vapor diffusion of i-propyl ether into acetonitrile for 3 weeks. The crystal structure (Figures 2d–f, S5, and S6) provides direct evidence for the formation of the metallacage. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the crystal structure of porphyrin-based multicomponent Pt(II)-metallacage is resolved.63−65 The two porphyrinic and biphenyl units are connected by eight Pt atoms and the angles of N–Pt–O are 82.3–83.5°, forming a box-like metallacage with a dimension of 14.9 × 12.0 × 8.3 Å3, based on the distance between the Pt atoms. The two porphyrin panels in the metallacage are parallel with each other and the distance between the two panels is 8.1 Å, which is an ideal distance to enable π–π stacking interactions with encapsulated aromatic guests. Moreover, this type of connection offers two large windows, which assist the guest molecules to enter into the cavity to form stable host–guest complexes. The metallacages are aligned along with the windows to form nanochannels (Figure 2f), which may facilitate host–guest complexation in the solid state.

UV/vis and fluorescence spectra (Figure S7) of ligand 1 and metallacage 4 were further collected to study their photophysical properties. Ligand 1 and metallacage 4 showed a strong Soret peak centered at ca. 417 nm and four Q bands centered at ca. 650, 590, 550, and 515 nm, respectively, which are the typical absorption of porphyrin derivatives.73 Two emission peaks at 655 and 717 nm were observed for 1 and 4. Since porphyrin derivatives can generate singlet oxygen effectively upon photoirradiation,74 the 1O2 generation capabilities of 1 and 4 were studied by collecting the phosphorescence emission spectra of 1O2. An intense peak at 1270 nm (Figure S8) was observed for both 1 and 4 upon irradiation (λex = 405 nm), consisting of the photodegradation of 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran using two photosensitizers (Figures S9 and S10), suggesting the strong 1O2 generation ability of both the ligand and the metallacage.

Host–Guest Properties of Metallacage 4

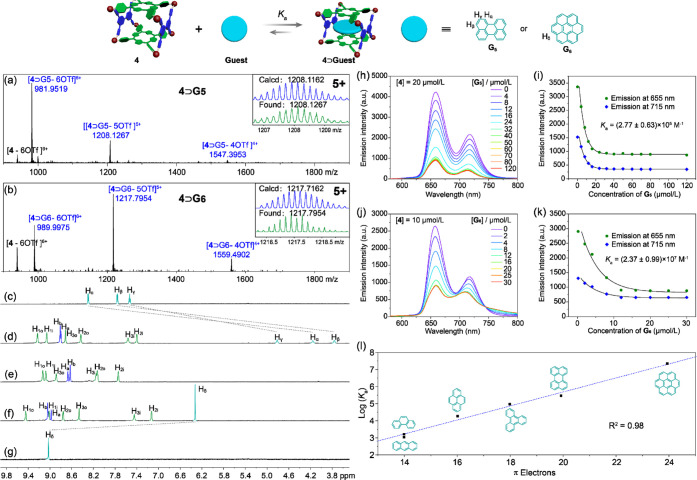

Considering that metallacage 4 possesses a box-shaped cavity and two electron-rich porphyrin faces, its complexation with PAHs including anthracene (G1), phenanthrene (G2), pyrene (G3), triphenylene (G4), perylene (G5), and coronene (G6) was further studied. Taking coronene as an example, when it was added to the acetonitrile solution of 4, a color change from claret-red to brown was observed, suggesting the charge-transfer interactions between 4 and G6. Job’s plots based on UV/vis spectroscopic absorbance data (λ = 417 nm) were carried out, indicating that the complexes of 4 with PAHs in acetonitrile were all of 1:1 stoichiometries (Figures S11–S16). This was also confirmed by ESI-TOF-MS (Figures 3a,b and S17). For example, peaks were observed at m/z 989.9975, 1217.7954, and 1559.4902 (Figure 3b), corresponding to [4⊃G6 – 6OTf]6+, [4⊃G6 – 5OTf]5+, and [4⊃G6 – 4OTf]4+. The complexation between metallacage 4 and PAHs was further studied by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figures 3c–g and S18–S23). All complexation systems exhibit fast exchange on the proton NMR timescale because the large windows of the metallacage make it easy for the guests to get in and out. Significant upfield shifts were observed for all of the resonances of the bound guests, indicating good host–guest interactions. For example, protons Hα, Hβ, and Hγ of G5 and proton Hδ of G6 shifted from 8.30, 7.76, 7.53, and 9.03 ppm to 4.16, 3.76, 4.81, and 6.32 ppm, respectively. Correspondingly, all of the resonances of metallacage 4 undergo significant changes with downfield or upfield shifts. These results indicated that the cavity of 4 provided a shielded magnetic environment for the guests.

Figure 3.

ESI-TOF-MS spectra of (a) 4⊃G5 and (b) 4⊃G6; partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, CD3CN, 298 K) of (c) G5, (d) 4⊃G5, (e) 4, (f) 4⊃G6, and (g) G6. [Host] = [Guest] = 1.00 mM. Fluorescence spectra of metallacage 4 at a fixed concentration upon the addition of (h) G5 and (j) G6 in CH3CN/CHCl3 (ν/ν = 9/1); nonlinear fitting curves of the emission intensity at 655 and 715 nm of metallacage 4 versus the concentrations of (i) G5 and (k) G6; and (l) plots of the logarithms of the association constants versus the number of π electrons on PAHs in CH3CN/CHCl3 (ν/ν = 9/1).

Concentration-dependent fluorescence titration experiments were carried out to measure the association constants (Ka) between metallacage 4 and PAHs in solution. For a better comparison, CH3CN/CHCl3 (ν/ν = 9/1) was used as the solvent owing to the poor solubility of large PAHs such as perylene and coronene in acetonitrile. The fluorescence intensity of metallacage 4 decreased gradually upon the addition of the guests. The Ka of 4⊃G1, 4⊃G2, 4⊃G3, 4⊃G4, 4⊃G5, and 4⊃G6 were determined as (1.19 ± 0.06) × 103, (1.55 ± 0.04) × 103, (1.94 ± 0.09) × 104, (9.33 ± 0.74) × 104, (2.77 ± 0.63) × 105, and (2.37 ± 0.99) × 107 M–1, respectively (Figures 3h–l and S28–S33). It is worth noting that these values are among the highest binding constants for metallacage-based host–guest complexes.46,75 This is because the two porphyrin faces in the metallacage are well organized in an ideal distance to promote the π–π stacking interactions with encapsulated PAHs. Interestingly, the values of log Ka are linearly proportional to the number of π-electrons on PAHs (Figure 3l and Table 1) with a correlation coefficient of 0.98. This could be used to predict the association constants between metallacage and PAHs.

Table 1. Association Constants between Metallacage 4 and Different PAHs.

| association

constant (Ka, M–1) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| guest molecules | number of π electrons | CH3CN | CH3CN/CHCl3 (ν/ν = 9/1) |

| G1 | 14 | (4.72 ± 0.11) × 103 | (1.19 ± 0.6) × 103 |

| G2 | 14 | (9.05 ± 0.27) × 103 | (1.55 ± 0.04) × 103 |

| G3 | 16 | (9.37 ± 1.67) × 104 | (1.94 ± 0.09) × 104 |

| G4 | 18 | (6.66 ± 3.53) × 105 | (9.33 ± 0.74) × 104 |

| G5 | 20 | (2.77 ± 0.63) × 105 | |

| G6 | 24 | (2.37 ± 0.99) × 107 | |

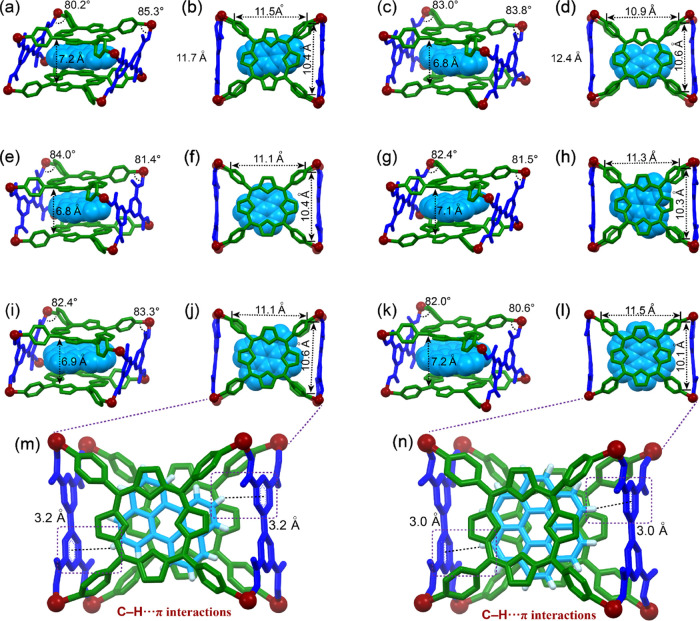

The single crystals of metallacage 4 with a series of PAHs suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were also obtained by vapor diffusion of i-propyl ether into acetonitrile for 3 weeks and provided unambiguous evidence for the formation of inclusion complexes. Ranging from three to seven fused benzenoid rings, the crystalline complexes (Figure 4) formed between metallacage 4 and various PAHs with a 1:1 stoichiometry were isolated. It is worth mentioning that the distance between the two porphyrin faces decreased from ca. 8.1 to 7.0 Å after complexation. Correspondingly, the distances between the PAHs and porphyrin faces are 3.4–3.6 Å, which meets the requirements for π–π stacking interactions. It can be seen from the top views of crystal structures (Figure 4) that the PAHs align themselves in register with the maximum number of binding sites in metallacage 4 by translational positioning or rotational location. In the crystal structures, anthracene, phenanthrene, pyrene, and triphenylene are disordered, leading to the broad signals of the protons on these guests in the 1H NMR spectra (Figures S18–S21) after complexation. However, for perylene and coronene, extra [C–H···π] interactions were also found between their peripheral protons and the phenyl rings of the carboxylic ligands to stabilize the whole complexes in addition to the π–π stacking interactions (Figure 4m,n). Therefore, the movements of perylene or coronene inside the cavity are restricted, giving sharp signals of the guests in the 1H NMR spectra (Figures 3c–g, S22, and S23).

Figure 4.

Crystal structures of (a, b) 4⊃G1, (c, d) 4⊃G2, (e, f) 4⊃G3, (g, h) 4⊃G4, (i, j, m) 4⊃G5, and (k, l, n) 4⊃G6. Hydrogen atoms, triethylphosphine units, counterions, and solvent molecules were omitted for clarity.72

Photooxidation-Triggered Encapsulation and Release

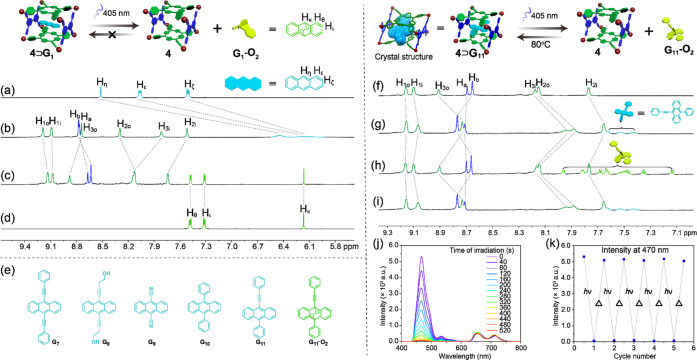

The stimuli responsiveness of such host–guest complexation was further explored. As the metallacage can generate 1O2 effectively, the oxidation of anthracene inside the metallacage was conducted (Figure 5a–d). The encapsulated anthracene fully converted into epidioxyanthracene upon photoirradiation (λex = 405 nm) for 10 min, as revealed from the fact that all of the peaks of the protons for anthracene disappeared and the peaks of the protons for epidioxyanthracene emerged (Figure 5b,c). It is worth mentioning that the chemical shifts of the epidioxyanthracene protons located at the same position with free epidioxyanthracene (Figure 5c,d), suggesting that epidioxyanthracene was released from the cavity of the metallacage after oxidation. This was also evidenced by the DOSY experiments (Figures S34 and S35) that epidioxyanthracene showed a different diffusion coefficient (D = 2.31 × 10–9 m2 s–1) from that of metallacage 4 (D = 6.21 × 10–10 m2 s–1), while the complex 4⊃anthracene only exhibits one single diffusion coefficient (D = 6.55 × 10–10 m2 s–1). However, epidioxyanthracene would decompose upon heating,76 so the reencapsulation process cannot take place using anthracene as the guest.

Figure 5.

Partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, CD3CN, 295 K) of (a) G1, (b) 4⊃G1, and (c) 4⊃G1 upon photoirradiation for 10 min and (d) epidioxyanthracene G1–O2. (e) Chemical structures of anthracene derivatives tested in the reversible controlled release study. Partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, CD3CN, 295 K) of (f) 4, (g) 4⊃G11, and (h) 4⊃G11 upon photoirradiation for 20 min, (i) and heating at 80°C for 30 min. (j, k) Fatigue cycles for the reversible host–guest system characterized by fluorescence spectroscopy. [Host] = [Guest] = 10.00 M, λex = 405 nm.

To construct a reversible photooxidation-triggered host–guest complexation, we screened several anthracene derivatives (Figure 5e) to find a suitable guest for the metallacage. Compounds G7, G8, and G9 showed good host–guest interactions with metallacage 4 (Figures S41–S44). Compounds G7 and G8 could be converted into their epidioxyanthracene analogues upon irradiation at 405 nm. However, their endoperoxides would undergo fast deoxidation to their original structures at room temperature. The encapsulated G9 failed to be converted into its endoperoxide upon irradiation, owing to its high stability. Due to steric hindrance of the benzene rings on both sides, G10 showed a poor host–guest interaction with metallacage 4 (Figure S45). Therefore, 10-phenyl-9-(2-phenylethynyl)anthracene (G11) was chosen as the guest for the construction of this reversible host–guest complex because its endoperoxide G11–O2 showed moderate stability at room temperature and could be converted back to G11 upon heating quickly (Figures S46 and S51).77

Compound G11 also formed stable 1:1 host–guest complexes (Figure S46) with metallacage 4. This was confirmed by ESI-TOF-MS as well (Figure S46c). Peaks were observed at m/z 998.3403, 1227.8087, 1572.0200, and 2145.6626, corresponding to [4⊃G11 – 6OTf]6+, [4⊃G11 – 5OTf]5+, [4⊃G11 – 4OTf]4+, and [4⊃G11 – 3OTf]3+. Single crystals of metallacage 4 with G11 suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were also obtained and provided unambiguous evidence for the formation of inclusion complex 4⊃G11 with a 1:1 stoichiometry (Figure S46d,e). The Ka of 4⊃G11 was determined to be (5.48 ± 0.31) × 103 M–1 (Figures S49 and S50), which was similar to that of 4⊃G1 in acetonitrile. When complex 4⊃G11 was irradiated for 20 min (λex = 405 nm, Figure 5f–i) in air at atmospheric pressure, 1O2 generated by the metallacage converted G11 into G11–O2 completely, leading to the release of the guest from its cavity. Upon heating at 80 °C for 30 min, G11–O2 was transferred back into G11 and the host–guest complex 4⊃G11 formed again (Figure 5h,i). These processes were also confirmed by the fluorescence experiments. The emission intensity at 470 nm derived from compound G11 decreased gradually upon photoirradiation, while the emission band at 660 nm ascribed to metallacage 4 was almost constant, suggesting the transformation of G11 into its endoperoxide (Figure 5j). After heating, the emission of the solution was restored to its initial value (Figure S51). This process is fully reversible and could be repeated at least five times with a good fatigue resistance (Figure 5k). Therefore, photooxidation-triggered reversible host–guest complexation was successfully prepared, which holds great potential for the construction of photoresponsive smart materials.

Conclusions

In summary, a box-shaped porphyrin-based metallacage was prepared by a multicomponent coordination-driven self-assembly. Owing to its electron-rich planar porphyrin face and suitable cavity size, the metallacage showed enhanced host–guest interactions with a series of PAHs. It was further employed to construct a reversible photoresponsive host–guest complexation system based on the photooxidation-triggered release of anthracene derivatives and the reencapsulation of guests upon heating. Our ongoing study reveals that different metalloporphyrins can also be introduced for the construction of such metallacages, suggesting the versatility of the multicomponent strategy in the construction of barrel-shaped metallacages. We believe that our current study offers a photoresponsive host–guest system, which is driven by the structural changes of guest molecules via photooxidation, which will guide the future design and applications of metallacages for stimuli-responsive materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Gang Chang and Yu Wang at the Instrument Analysis Center and Dr. Aqun Zheng and Junjie Zhang at the Experimental Chemistry Center of Xi’an Jiaotong University for NMR and fluorescence measurements. The authors also acknowledge the mass spectrometry characterization by the Molecular Scale Laboratory.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacsau.2c00245.

Experimental details and characterization, spectra (1H NMR, 13C NMR, ESI-MS spectra, UV–vis absorption, and fluorescence spectra) (PDF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G1 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G2 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G3 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G4 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G5 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G6 (CIF)

Crystal diffraction data for 4⊃G11 (CIF)

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22171219 to M.Z.), the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Supramolecular Structure and Materials (sklssm2021033), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Huang F.; Anslyn E. V. Introduction: Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6999–7000. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.; Nalluri S. K. M.; Stoddart J. F. Surveying Macrocyclic Chemistry: From Flexible Crown Ethers to Rigid Cyclophanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2459–2478. 10.1039/C7CS00185A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia D.; Wang P.; Ji X.; Khashab N. M.; Sessler J. L.; Huang F. Functional Supramolecular Polymeric Networks: The Marriage of Covalent Polymers and Macrocycle-Based Host-Guest Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6070–6123. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty M. A.; Hof F. Host–Guest Binding in Water, Salty Water, and Biofluids: General Lessons for Synthetic, Bio-targeted Molecular Recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4812–4832. 10.1039/D0CS00495B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen C. J. Cyclic Polyethers and Their Complexes with Metal Salts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 7017–7036. 10.1021/ja01002a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lehn J. M. Cryptates: The Chemistry of Macropolycyclic Inclusion Complexes. Acc. Chem. Res. 1978, 11, 49–57. 10.1021/ar50122a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He Q.; Vargas-Zúñiga G. I.; Kim S. H.; Kim S. K.; Sessler J. L. Macrocycles as Ion Pair Receptors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9753–9835. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochowicz D.; Kornowicz A.; Lewiński J. Interactions of Native Cyclodextrins with Metal Ions and Inorganic Nanoparticles: Fertile Landscape for Chemistry and Materials Science. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13461–13501. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy I.; Stoddart J. F. Cyclodextrin Metal–Organic Frameworks and Their Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1440–1453. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D.-S.; Liu Y. Supramolecular Chemistry of p-Sulfonatocalix[n]arenes and Its Biological Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1925–1934. 10.1021/ar500009g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R.; Sharma A.; Singh H.; Suating P.; Kim H. S.; Sunwoo K.; Shim I.; Gibb B. C.; Kim J. S. Revisiting Fluorescent Calixarenes: from Molecular Sensors to Smart Materials. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 9657–9721. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrow S. J.; Kasera S.; Rowland M. J.; Del Barrio J.; Scherman O. A. Cucurbituril-Based Molecular Recognition. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12320–12406. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J.; Kim K.; Ogoshi T.; Yao W.; Gibb B. C. The Aqueous Supramolecular Chemistry of Cucurbit[n]urils, Pillar[n]arenes and Deep-Cavity Cavitands. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2479–2496. 10.1039/C7CS00095B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale E. J.; Vermeulen N. A.; Juricek M.; Barnes J. C.; Young R. M.; Wasielewski M. R.; Stoddart J. F. Supramolecular Explorations: Exhibiting the Extent of Extended Cationic Cyclophanes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 262–273. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai K.; Zhang L.; Astumian R. D.; Stoddart J. F. Radical-Pairing-Induced Molecular Assembly and Motion. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 447–465. 10.1038/s41570-021-00283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoshi T.; Yamagishi T.; Nakamoto Y. Pillar-Shaped Macrocyclic Hosts Pillar[n]arenes: New Key Players for Supramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 7937–8002. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fa S.; Kakuta T.; Yamagishi T.-a.; Ogoshi T. One-, Two-, and Three-Dimensional Supramolecular Assemblies Based on Tubular and Regular Polygonal Structures of Pillar[n]arenes. CCS Chem. 2019, 1, 50–63. 10.31635/ccschem.019.20180014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You L.; Zha D.; Anslyn E. V. Recent Advances in Supramolecular Analytical Chemistry Using Optical Sensing. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7840–7892. 10.1021/cr5005524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mako T. L.; Racicot J. M.; Levine M. Supramolecular Luminescent Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 322–477. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. R.; Yang Y. W. Synthetic Macrocycle-Based Nonporous Adaptive Crystals for Molecular Separation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1690–1701. 10.1002/anie.202006999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer C. C.; Smith B. D. Macrocyclic and Acyclic Supramolecular Elements for Co-precipitation of Square-Planar Gold(iii) Tetrahalide Complexes. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1294–1301. 10.1039/D0QO01562H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Si W.; Xin P.; Li Z.-T.; Hou J.-L. Tubular Unimolecular Transmembrane Channels: Construction Strategy and Transport Activities. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1612–1619. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barboiu M. Encapsulation versus Self-Aggregation toward Highly Selective Artificial K+ Channels. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2711–2718. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber M. J.; Langer R. Drug Delivery by Supramolecular Design. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6600–6620. 10.1039/C7CS00391A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omoto K.; Tashiro S.; Shionoya M. Phase-Dependent Reactivity and Host-Guest Behaviors of a Metallo-Macrocycle in Liquid and Solid-State Photosensitized Oxygenation Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5406–5412. 10.1021/jacs.0c13338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra B.; Cao L.; Cannon J. R.; Zavalij P. Y.; Fenselau C.; Isaacs L. Synthesis and Self-Assembly Processes of Monofunctionalized Cucurbit[7]uril. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13133–13140. 10.1021/ja3058502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L.; Hettiarachchi G.; Briken V.; Isaacs L. Cucurbit[7]uril Containers for Targeted Delivery of Oxaliplatin to Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12033–12037. 10.1002/anie.201305061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook T. R.; Stang P. J. Recent Developments in the Preparation and Chemistry of Metallacycles and Metallacages via Coordination. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 7001–7045. 10.1021/cr5005666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. A.; Pilgrim B. S.; Nitschke J. R. Covalent Post-Assembly Modification in Metallosupramolecular Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 626–644. 10.1039/C6CS00907G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. J.; Yang H. B. Construction of Stimuli-Responsive Functional Materials via Hierarchical Self-Assembly Involving Coordination Interactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2699–2710. 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Chen C.; Liu J.; Stang P. J. Recent Developments in the Construction and Applications of Platinum-Based Metallacycles and Metallacages via Coordination. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 3889–3919. 10.1039/D0CS00038H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. J.; Chen S.; Qin Y.; Xu L.; Yin G. Q.; Zhu J. L.; Zhu F. F.; Zheng W.; Li X.; Yang H. B. Construction of Porphyrin-Containing Metallacycle with Improved Stability and Activity within Mesoporous Carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5049–5052. 10.1021/jacs.8b02386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Chen C.; Sun Y.; Lu S.; Huo H.; Tan T.; Li A.; Li X.; Ungar G.; Liu F.; Zhang M. Luminescent Metallacycle-Cored Liquid Crystals Induced by Metal Coordination. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10143–10150. 10.1002/anie.201915055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyakkumar P.; Liang Y.; Guo M.; Lu S.; Xu D.; Li X.; Guo B.; He G.; Chu D.; Zhang M. Emissive Metallacycle-Crosslinked Supramolecular Networks with Tunable Crosslinking Densities for Bacterial Imaging and Killing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15199–15203. 10.1002/anie.202005950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B.; Liu X.; Yang G.; Tian J.; Liu Z.; Zhu Y.; Li X.; Yin G.; Zheng W.; Xu L.; Zhang W. A Near-Infrared Organoplatinum(II) Metallacycle Conjugated with Heptamethine Cyanine for Trimodal Cancer Therapy. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 2055–2066. 10.31635/ccschem.021.202100950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Tuo W.; Stang P. J. Metal-Organic Cycle-Based Multistage Assemblies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2122398119 10.1073/pnas.2122398119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuma Y.; Kawano M.; Fujita M. Crystalline Molecular Flasks. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 349–358. 10.1038/nchem.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. J.; Toste F. D.; Bergman R. G.; Raymond K. N. Supramolecular Catalysis in Metal-Ligand cluster Hosts. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3012–3035. 10.1021/cr4001226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.; Jiang S.; Zhang Z.; Hao X.-Q.; Jiang X.; Yu H.; Wang P.; Xu B.; Wang M.; Tian W. Tetraphenylethylene-Based Emissive Supramolecular Metallacages Assembled by Terpyridine Ligands. CCS Chem. 2020, 2, 337–348. 10.31635/ccschem.020.201900109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Zhao Z.; Hou Y.; Wang H.; Li X.; He G.; Zhang M. Aqueous Platinum(II)-Cage-Based Light-Harvesting System for Photocatalytic Cross-Coupling Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 8862–8866. 10.1002/anie.201904407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y.; Zhang Z.; Lu S.; Yuan J.; Zhu Q.; Chen W.-P.; Ling S.; Li X.; Zheng Y.-Z.; Zhu K.; Zhang M. Highly Emissive Perylene Diimide-Based Metallacages and Their Host-Guest Chemistry for Information Encryption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 18763–18768. 10.1021/jacs.0c09904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Zhao Z.; Wu L.; Lu S.; Ling S.; Li G.; Xu L.; Ma L.; Hou Y.; Wang X.; Li X.; He G.; Wang K.; Zou B.; Zhang M. Emissive Platinum(II) Cages with Reverse Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer for Multiple Sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2592–2600. 10.1021/jacs.9b12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y.; Zhang Z.; Ma L.; Shi R.; Ling S.; Li X.; He G.; Zhang M. Perylene Diimide-Based Multicomponent Metallacages as Photosensitizers for Visible Light-Driven Photocatalytic Oxidation Reaction. CCS Chem. 2021, 3153–3160. 10.31635/ccschem.021.202101382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mu C.; Zhang Z.; Hou Y.; Liu H.; Ma L.; Li X.; Ling S.; He G.; Zhang M. Tetraphenylethylene-Based Multicomponent Emissive Metallacages as Solid-State Fluorescent Materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 12293–12297. 10.1002/anie.202100463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T.; Ube H.; Shionoya M. Silver-Mediated Formation of a Cofacial Porphyrin Dimer with the Ability to Intercalate Aromatic Molecules. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12096–12100. 10.1002/anie.201306510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- August D. P.; Nichol G. S.; Lusby P. J. Maximizing Coordination Capsule-Guest Polar Interactions in Apolar Solvents Reveals Significant Binding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15022–15026. 10.1002/anie.201608229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez S.; Peris E. A Rigid Trigonal-Prismatic Hexagold Metallocage That Behaves as a Coronene Trap. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6693–6697. 10.1002/anie.201902568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L. X.; Yan D. N.; Cheng P. M.; Xuan J. J.; Li S. C.; Zhou L. P.; Tian C. B.; Sun Q. F. Controlled Self-Assembly and Multistimuli-Responsive Interconversions of Three Conjoined Twin-Cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 2016–2024. 10.1021/jacs.0c12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purba P. C.; Maity M.; Bhattacharyya S.; Mukherjee P. S. A Self-Assembled Palladium(II) Barrel for Binding of Fullerenes and Photosensitization Ability of the Fullerene-Encapsulated Barrel. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 14109–14116. 10.1002/anie.202103822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldacre A. N.; Friedman A. E.; Cook T. R. A Self-Assembled Cofacial Cobalt Porphyrin Prism for Oxygen Reduction Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1424–1427. 10.1021/jacs.6b12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L. X.; Li S. C.; Yan D. N.; Zhou L. P.; Guo F.; Sun Q. F. A Water-Soluble Redox-Active Cage Hosting Polyoxometalates for Selective Desulfurization Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4869–4876. 10.1021/jacs.8b00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.; Fan Y. Z.; Lu Y. L.; Zheng S. P.; Su C. Y. Visible-Light Photocatalysis of Asymmetric [2+2] Cycloaddition in Cage-Confined Nanospace Merging Chirality with Triplet-State Photosensitization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8661–8669. 10.1002/anie.201916722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu D.; Gong W.; Jiang H.; Tang X.; Cui Y.; Liu Y. Boosting Enantioselectivity of Chiral Molecular Catalysts with Supramolecular Metal–Organic Cages. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 1692–1700. 10.31635/ccschem.021.202100847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howlader P.; Mondal B.; Purba P. C.; Zangrando E.; Mukherjee P. S. Self-Assembled Pd(II) Barrels as Containers for Transient Merocyanine form and Reverse Thermochromism of Spiropyran. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 7952–7960. 10.1021/jacs.8b03946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S.; Meichsner S. L.; Holstein J. J.; Baksi A.; Kasanmascheff M.; Clever G. H. Long-Lived C60 Radical Anion Stabilized Inside an Electron-Deficient Coordination Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9718–9723. 10.1021/jacs.1c02860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durot S.; Taesch J.; Heitz V. Multiporphyrinic Cages: Architectures and Functions. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 8542–8578. 10.1021/cr400673y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percástegui E. G.; Jancik V. Coordination-Driven Assemblies Based on Meso-Substituted Porphyrins: Metal-Organic Cages and a New Type of Meso-Metallaporphyrin Macrocycles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 407, 213165 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.213165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. J.; Hupp J. T. Porphyrin-Containing Molecular Squares: Design and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 1710–1723. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bar A. K.; Chakrabarty R.; Mostafa G.; Mukherjee P. S. Self-Assembly of a Nanoscopic Pt12Fe12 Heterometallic Open Molecular Box Containing Six Porphyrin Walls. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8455–8459. 10.1002/anie.200803543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.; Hong K. I.; Jang W. D. Design and Applications of Molecular Probes Containing Porphyrin Derivatives. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 354, 46–73. 10.1016/j.ccr.2017.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes-Espinosa C.; Garcia-Simon C.; Pujals M.; Garcia-Borras M.; Gomez L.; Parella T.; Juanhuix J.; Imaz I.; Maspoch D.; Costas M.; Ribas X. Supramolecular Fullerene Sponges as Catalytic Masks for Regioselective Functionalization of C60. Chem 2020, 6, 169–186. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ubasart E.; Borodin O.; Fuertes-Espinosa C.; Xu Y.; Garcia-Simon C.; Gomez L.; Juanhuix J.; Gandara F.; Imaz I.; Maspoch D.; von Delius M.; Ribas X. A Three-Shell Supramolecular Complex Enables the Symmetry-Mismatched Chemo- and Regioselective Bis-Functionalization of C60. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 420–427. 10.1038/s41557-021-00658-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Sanchez-Molina I.; Cao C.; Cook T. R.; Stang P. J. Synthesis and Photophysical Studies of Self-Assembled Multicomponent Supramolecular Coordination Prisms Bearing Porphyrin Faces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 9390–9395. 10.1073/pnas.1408905111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G.; Yu S.; Saha M. L.; Zhou J.; Cook T. R.; Yung B. C.; Chen J.; Mao Z.; Zhang F.; Zhou Z.; Liu Y.; Shao L.; Wang S.; Gao C.; Huang F.; Stang P. J.; Chen X. A Discrete Organoplatinum(II) Metallacage as a Multimodality Theranostic Platform for Cancer Photochemotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4335 10.1038/s41467-018-06574-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Chen C.; Liu J.; Liu L.; Tuo W.; Zhu H.; Lu S.; Li X.; Stang P. J. Self-Assembly of Porphyrin-Based Metallacages into Octahedra. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17903–17907. 10.1021/jacs.0c08058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides P. A.; Gordillo M. A.; Yadav A.; Joaqui-Joaqui M. A.; Saha S. Pt(ii)-Coordinated Tricomponent Self-Assemblies of Tetrapyridyl Porphyrin and Dicarboxylate Ligands: are They 3D Prisms or 2D Bow-ties?. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 4070–4081. 10.1039/D1SC06533E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S.; Tada T.; Komoto Y.; Osuga T.; Murase T.; Fujita M.; Kiguchi M. Rectifying Electron-Transport Properties through Stacks of Aromatic Molecules Inserted into a Self-Assembled Cage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5939–5947. 10.1021/jacs.5b00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spenst P.; Würthner F. A Perylene Bisimide Cyclophane as a “Turn-On” and “Turn-Off” Fluorescence Probe. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10165–10168. 10.1002/anie.201503542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.; Ronson T. K.; Lavendomme R.; Nitschke J. R. Selective Separation of Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons by Phase Transfer of Coordination Cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18949–18953. 10.1021/jacs.9b10741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Wang H.; Zhong J.; Lei Y.; Du R.; Zhang Y.; Shen L.; Jiao T.; Zhu Y.; Zhu H.; Li H.; Li H. A Mutually Stabilized Host-Guest Pair. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax6707 10.1126/sciadv.aax6707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Bobbala S.; Stern C. L.; Hornick J. E.; Liu Y.; Enciso A. E.; Scott E. A.; Stoddart J. F. XCage: A Tricyclic Octacationic Receptor for Perylene Diimide with Picomolar Affinity in Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3165–3173. 10.1021/jacs.9b12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deposition Numbers 2102359 (for 4), 2102363 (for 4⊃G1), 2109173 (for 4⊃G2), 2109174 (for 4⊃G3), 2109177 (for 4⊃G4), 2109175 (for 4⊃G5), 2109178 (for 4⊃G6), and 2161223 (for 4⊃G11) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures Service. www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/.

- Hiroto S.; Miyake Y.; Shinokubo H. Synthesis and Functionalization of Porphyrins through Organometallic Methodologies. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2910–3043. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghogare A. A.; Greer A. Using Singlet Oxygen to Synthesize Natural Products and Drugs. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 9994–10034. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen W.; Turega S.; Hunter C. A.; Ward M. D. Virtual Screening for High Affinity Guests for Synthetic Supramolecular Receptors. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 2790–2794. 10.1039/C5SC00534E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudickar W.; Linker T. Why Triple Bonds Protect Acenes from Oxidation and Decomposition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 15071–15082. 10.1021/ja306056x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaper M.; Linker T. Intramolecular Transfer of Singlet Oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13744–13747. 10.1021/jacs.5b07848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.