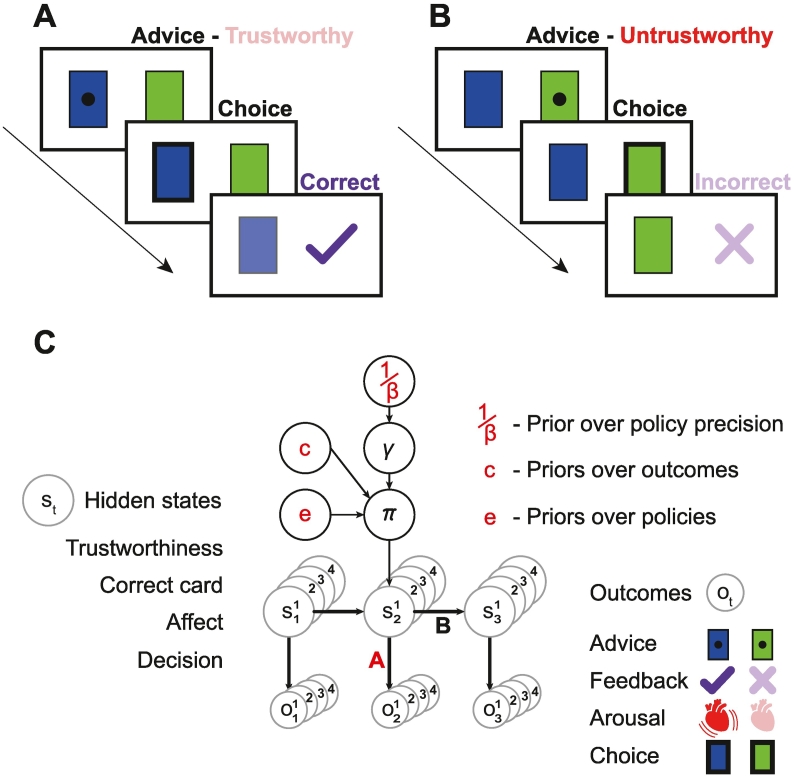

Fig. 1.

Task and model structure.

A – The sequence of events within one trial, consisting of three timesteps. First, the agent receive advice to choose the blue card. Unbeknownst to the agent, the advisor is ‘trustworthy’. Next, the agent chooses the blue card, and then gets ‘correct’ feedback.

B – The sequence of events with an ‘untrustworthy’ advisor. The agent follows the advice and gets ‘incorrect’ feedback.

C – A schematic of the Markov decision process active inference model, during one trial (see the text and Supplement for a full description). Each trial consists of three timesteps. The exteroceptive and interoceptive outcomes o that the agent observes in each trial are shown at the bottom and listed on the right: they comprise the advice received, the feedback received, the arousal state (high or low), and the choice the agent makes. The agent must infer the hidden states s generating these outcomes: these states include the advisor's trustworthiness, the correct card, the agent's own affective state, and the agent's decision of which card to choose. The probabilistic (or deterministic) mappings from states to outcomes is given by the likelihood matrices in A. The transitions in hidden states across timesteps are given by the transition matrices in B. Some of these transitions depend on the agent's policy π, which is a sequence of control states u (e.g., ‘trust the advisor, choose blue’) across the three timesteps. The agent's choice of policy depends on its inferences about states s but also its priors over policies (or habits) Dir(e), its priors over outcomes (or preferences) c, and precision of (i.e., confidence in) its policies γ, which is heavily influenced by the prior over this precision, 1/β. For example, if an agent has trusted the advisor and/or chosen blue many times more than the other choices, its prior over these choices will be strengthened by the accumulation of counts in Dir(e). The agent is also strongly influenced by its priors over outcomes c, in which it expects to receive ‘correct’ feedback rather ‘incorrect’ feedback by a factor of exp(6). The agents with a negative ‘mood’ also predict ‘high’ arousal states to be more likely than ‘low’ (or vice versa, for positive mood). The precision over policies γ is continually updated, and denotes the agent's confidence that its policy will fulfil its priors over outcomes: a higher γ means it will choose its favoured policy more deterministically. The parameters coloured in red are later shown to contribute to false inferences: i.e., weaker likelihood (a) in A, and stronger influences of priors Dir(e), mood (c) in c and 1/β. Choice precision α is not shown. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)