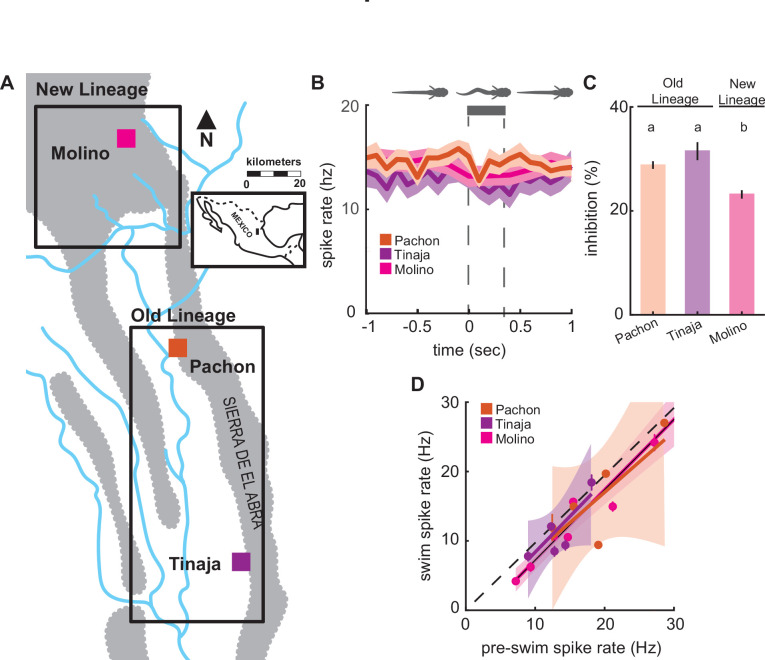

Figure 5. Enhanced lateral line sensitivity during swimming convergently evolved across three blind populations.

(A) Molino cave populations (pink; New Lineage) have evolved more recently relative to Pachón (red) and Tinaja (purple; Old Lineage) cave populations. Lineage delineations inferred from phylogenetic data (Herman et al., 2018). (B) Mean spontaneous afferent spike rate remains constant at the onset of fictive swimming (time = 0) in Pachón (n = 5), Molino (n = 8), and Tinaja (n = 5) populations (N-way ANOVA: p = 0.52).Bar represents average swim duration for Pachón (0.27 s, n = 2429 swim bouts), Molino (0.42 s, n = 1,474 swim bouts), and Tinaja (0.35 s, n = 464). (C) Percent change in spike rate from pre-swim to swim intervals (i.e., inhibition) was small, but significantly different between blind cave populations. Post hoc Tukey test revealed that Molino cavefish experienced significantly less reduction in spike rate when compared to Pachón and Tinaja populations (p < 0.01). Statistically similar groups are indicated by ‘a’ and ‘b’. (D) The line of best fit of pre-swim and swim spike rates does not significantly exclude unity in any of the blind cavefish populations implying there is no detectable inhibitory effect (Pachón: CI = -0.5 to 2.2, Tinaja: CI = -0.2 to 2.2, Molino: CI = 0.8 to 1.2). Dashed line indicates the line of unity, corresponding to no average difference of spike rate during swimming. All values represent mean ± standard error (SE).