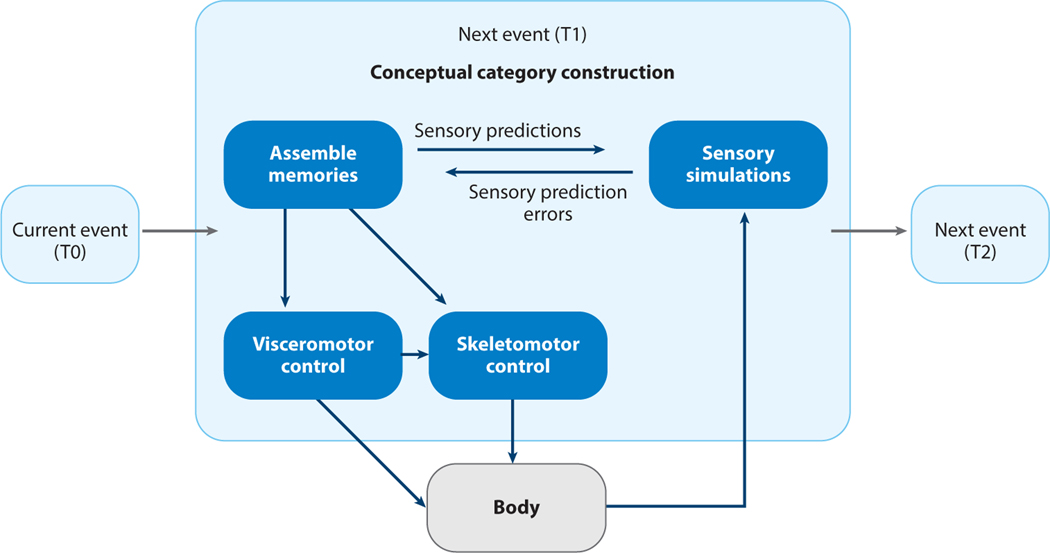

Figure 2.

Toy example of predictive processing within the cerebral cortex. In this example, the present moment is time zero (T0). At T0, a brain’s internal model is representing its confirmed beliefs about the current sensory conditions of the body and the world as it generatively constructs a population of prediction signals by using past experiences of temporal dependencies, based on similarities (or features of equivalence). Figuratively speaking, the brain is asking itself, “In similar past events, what actions did I make next?” Neurons whose cell bodies reside in the deep layers of the cerebral cortex send motor prediction signals (as preparations for both visceromotor and skeletomotor actions) that cascade to subcortical regions and the spinal cord via neurons as they become more detailed and particularized. These neurons in the deep layers of the cerebral cortex have collateral axons that send the same information, called efferent copies of the motor prediction signals, to more granular parts of the cerebral cortex, becoming more detailed and particularized, until they reach primary sensory regions (Barbas 2015) (see Figure 3). These efferent copies can be understood as sensory prediction signals that infer the sensory consequences of the motor predictions (i.e., what a brain expects to see, hear, feel, and so forth if these motor actions are enacted, estimated from the statistical regularities in past experiences). These efferent copies are also called simulations or perceptual inferences because this signal changes the firing of sensory neurons in advance of sense data that will arrive momentarily from the body’s sensory surfaces. Figure adapted with permission from Hutchinson & Barrett (2019).