Abstract

Background

Early assessment and management of patients with sepsis can significantly reduce its high mortality rates and improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

Objectives

The purposes of this review are to: (1) explore nurses’ knowledge, attitude, practice, and perceived barriers and facilitators related to early recognition and management of sepsis, (2) explore different interventions directed at nurses to improve sepsis management.

Methods

A systematic review method according to the PRISMA guidelines was used. An electronic search was conducted in March 2021 on several databases using combinations of keywords. Two researchers independently selected and screened the articles according to the eligibility criteria.

Results

Nurses reported an adequate of knowledge in certain areas of sepsis assessment and management in critically ill adult patients. Also, nurses’ attitudes toward sepsis assessment and management were positive in general, but they reported some misconceptions regarding antibiotic use for patients with sepsis, and that sepsis was inevitable for critically ill adult patients. Furthermore, nurses reported they either were not well-prepared or confident enough to effectively recognize and promptly manage sepsis. Also, there are different kinds of nurses’ perceived barriers and facilitators related to sepsis assessment and management: nurse, patient, physician, and system-related. There are different interventions directed at nurses to help in improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of sepsis assessment and management. These interventions include education sessions, simulation, decision support or screening tools for sepsis, and evidence-based treatment protocols/guidelines.

Discussion

Our findings could help hospital managers in developing continuous education and staff development training programs on assessing and managing sepsis in critical care patients.

Conclusion

Nurses have poor to good knowledge, practices, and attitudes toward sepsis as well as report many barriers related to sepsis management in adult critically ill patients. Despite all education interventions, no study has collectively targeted critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of sepsis management.

Introduction

Sepsis is a global health problem that increases morbidity and mortality rates worldwide and which is one of the most common complications documented in intensive care units (ICUs) [1]. About 48.9 million cases of sepsis and 11 million sepsis-related deaths were documented in 2017 worldwide [2]. Sepsis is an emergency condition leading to several life-threatening complications, such as septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction and failure [3]. Sepsis has negative physiological, psychological, and economic consequences. Untreated sepsis can lead to septic shock; multiple organ failure, such as acute renal failure [4]; respiratory distress syndrome [5]; cardiac arrhythmia (e.g. Atrial Fibrillation) [6]; and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [7]. Also, sepsis is associated with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [8]. As for the financial burden of sepsis on the healthcare system, the cost of healthcare services and supplies for ICU critical care patients with sepsis is high [1]. In 2017, the estimated annual cost of sepsis in the United States (US) was over $24 billion [2].

Previous studies have shown that among nurses, misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the early clinical manifestations of sepsis, poor knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis, and inadequate training might lead to delayed assessment and management of sepsis [9–11]. Moreover, the limited numbers of specific and sensitive assessment tools and standard protocols for the early identification and assessment of sepsis in critical care patients leads to delayed management, therefore increasing sepsis-related mortality rates [10].

Critical care nurses, as frontline providers of patient care, play a vital role in the decision-making process for the early identification and prompt management of sepsis [11]. Therefore, improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis is associated with improved patient outcomes [12, 13]. To date, there remains a wide gap between the findings of previous research and sepsis-related clinical practice in critical care units (CCUs). Furthermore, there is no evidence in the nursing literature regarding nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis in adult critical care patients and the association of these factors with patient health outcomes. Therefore, summarizing and synthesizing the existing research on sepsis assessment and management among adult critical care patients is needed to guide future directions of sepsis-related clinical practice and research. Accordingly, this review aims to identify nurses’ knowledge, and attitudes, practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis in adult critical care patients.

Materials and methods

The present review used a systematic review design guided by structured questions constructed after reviewing the nursing literature relevant to sepsis assessment and management in adult critical care patients. The authors (MR, DB, AH) carefully reviewed and evaluated the selected articles and synthesized and analyzed their findings to reach a consensus. This review was guided by the following questions: (a) what are nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management in adult critical care patients?, (b) what are the perceived facilitators of and barriers to the early identification and effective management of sepsis in adult critical care units?, and (c) what are the interventions directed at improving nurses’ sepsis assessment and management?

Eligibility criteria

The review questions were developed according to the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcome, and Study Design) framework, as displayed in Table 1.

Table 1. The construction of review questions according to PICOS framework.

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | patients aged 19 years and older who were admitted to critical care settings with sepsis, septic shock, or septicemia |

| Intervention | Training/educational interventions (e.g., regular lectures, simulations, algorithms, decision support tools, and sepsis protocol) |

| Comparison | No restriction was applied on the number or type of comparison group as the impact of the intervention could be determined. Comparison groups could include no intervention, standard protocol, and other types of intervention which was educational |

| Outcome | The primary outcomes of interest in this review were the effective assessment and prompt management of sepsis and nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, practice, perceived barriers, and enablers related to sepsis assessment and management. sepsis assessment and management could be assessed using either patient or nurse objective measures. Sepsis assessment and management were quantified as mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation, sepsis protocol adherence, and decline in mortality rate in-hospital sepsis-related complications. nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice related to sepsis could be assessed using either nurse-reported tools or performance-based tests, while nurses’ perceived barriers and enablers could be assessed using nurse-reported tools. |

| Study Design | Experimental, quasi-experimental, description. Cross-sectional, observational, prospective, qualitative, and mixed methods |

Inclusion criteria

The articles were retrieved and assessed independently by two researchers (MR, DB) according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) being written in English, (2) having an abstract and reference list, (3) having been published during the past 10 years, (4) focusing on critical care nurses as a target population, (5) examining knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the assessment and management of sepsis, and (6) having been conducted in adult critical care units.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they were (1) written in languages other than English, and (2) conducted in pediatric critical care units or non-ICU. Dissertations, reports, reviews, editorials, and brief communications were also excluded.

Search strategy

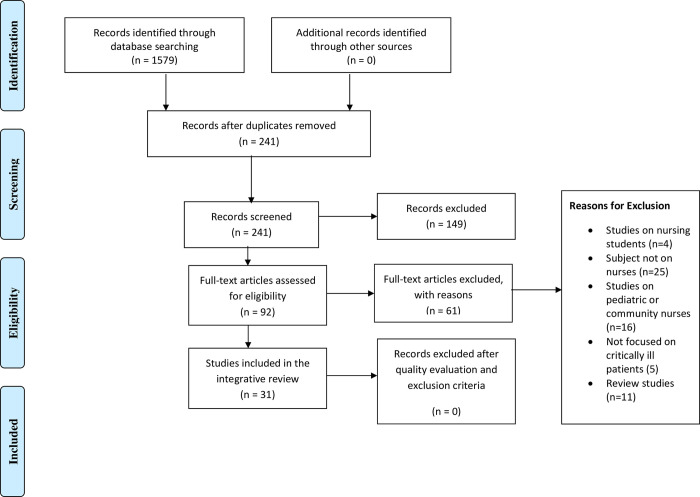

An electronic search of the databases CINAHL, MEDLINE/PubMed, EBSCO, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar was conducted using combinations of the following keywords: critical care, intensive care, critically ill, critical illness, knowledge, awareness, perception, understanding, attitudes, opinion, beliefs, thoughts, views, practice, skills, strategies, approaches, barriers, obstacles, challenges, difficulties, issues, problems, limitations, facilitators, motivators, enablers, sepsis, septic, septic shock, and septicemia. The search terms used in this review were described in S1 File. The search was initially conducted in March 2021, and a search re-run was conducted in April 2022. The search was conducted in the selected databases from inception to 4/2022. The initial search, using the keywords independently, resulted in 1579 articles, and after using the keyword combinations, this number was reduced to 241 articles. Then, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the number of articles was reduced to 92. A manual search of the reference lists of the 92 articles was carried out to identify any relevant publications not identified through the search. The researcher (MR) used the function “cited by” on Google Scholar to explore these publications in more depth. The researchers (MR, DB) then screened the identified citations of these publications, applying the eligibility criteria. In case of discrepancies, the researchers (MR, DB) discussed their conflicting points of view until a consensus was reached. Then, after careful reading of the article abstracts, 61 irrelevant articles were excluded, and a total of 31 articles were included in this review. Fig 1 below shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist and flow chart used as a method of screening and selecting the eligible studies.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each of the selected studies: (1) the general features of the article, including the authors and publication year; (2) the characteristics of the study setting (e.g., single vs. multisite); (3) the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the target population, including mean age, and medical diagnosis (e.g., sepsis, septic shock, and SIRS); (4) the name of the sepsis protocol used, if any; (5) the characteristics of the study methodology (e.g., sample size and measurements); (7) the main significant findings of the study; and (8) the study strengths and limitations. All extracted data were summarized in an evidence-based table (Table 2). Data extraction was performed by two researchers (MR, DB). An expert third researcher (AH) was consulted to reach a consensus between the two researchers throughout the process of data extraction.

Table 2. Summary of the reviewed studies.

| Study | Aim of the study | Design | LOE | Setting/Sample | Main findings | Strengths/Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delaney et al. (2015) | To determine the impact of an educational program on nurses’ assessment & management of sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 82 ER nurses/ USA | There was a significant improvement in nurses’ knowledge & competency related to the early recognition & management of sepsis after the educational program. |

weakness: use of self-report tools, purposive sample, homogeneity of sample. Strength: use of reliable and valid tool |

| Breen and Rees (2018) | To identify the barriers to the implementation of sepsis protocols | Cross-sectional | VI | 108 nurses in ACS/UK | Nurses’ poor knowledge & poor ability to recognize sepsis during observation round were the main barriers to prompt sepsis management |

Weakness: low response rate, heterogeneity of sample Strength: several geographical areas |

| Roney et al. (2020) | To evaluate the implementation of MEW-S in ACS | Quasi-experimental | III | 139 nurses in ACS/ USA | Implementation of MEW-S led to a significant improvement in sepsis assessment & management, thus decreasing mortality rate by 24% |

Weakness: one geographical site Strength: use reliable & valid tools |

| N. Roberts et al.(2017) | To identify the barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of the Sepsis Six at a case study hospital | Mixed method | VI | 13 ER nurses /USA | The main barriers were insufficient audit & feedback, poor teamwork & communication, & insufficient training & resources. Main facilitators were good confidence in knowledge & skills & positive beliefs towards sepsis bundles |

Weakness: one geographical site Strength: used mix methods design |

| van den Hengel et al. (2016) | To examine the factors influencing the knowledge & recognition of SIRS criteria & sepsis by ER nurses | Prospective -observational | IV | 216 ER nurses from 11 hospitals/ Netherlands | ER nurses aged over 50 had significantly lower scores in knowledge related to sepsis criteria than did younger nurses. Nurses working in hospitals with 3 level ICUs had more knowledge than did nurses working in hospitals with levels 1&2 ICUs. The educational program improved nurses’ knowledge of sepsis. |

Weakness: potential bias because multiple visits were made Strength: conducted in multi- center sites |

| Long et al. (2018) | To gain insight into clinical decision support systems-based alert and nurses’ perceptions | Cross-sectional | VI | 43 ER nurses/USA | Using clinical decision support systems-based alert improved nurses’ decision-making related to sepsis, thus leading to better outcomes | Weakness: not validated questionnaire, conducted in single center Strength: used interactive survey to collect data |

| Jacobs (2020) | To determine if implementing the NDS protocol reduces ACT readmission among patients with sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 238 patients with sepsis/ USA | Readmission rate among patients assessed & treated by NDS & who received early-goal directed therapy was reduced from 36.28% to 25% after 8 weeks. Nurses’ compliance with the intervention protocol was improved. | Weakness: the protocol used was not universally applied Strength: novelty of the study and use of protocol based on the golden criteria of the SSC |

| Amland et al. (2015) | To examine the diagnostic accuracy of two-stage clinical decision support systems for the early recognition & management of sepsis | Observational cohort study | IV | 417 patients with sepsis/ USA | Nurses completed 75% of assessment and screening within one hour of notification. The decision support system led to the early identification and timely, quality, and safe sepsis care |

Weakness: single center Strength: used sepsis alert with high positive predictive values |

| Delawder and Hulton (2020) | To test the effectiveness of sepsis bundle guidelines in the early assessment & treatment of sepsis. | Quasi-experimental | III | 214 ER patients /USA | There was an improvement in the time to implement sepsis guidelines, except for antibiotic administration & blood culture collection. Mortality rate decreased from 12.45% to 4.55% but no differences in mortality rate based on age or gender |

Weakness: single center Strength: used an interdisciplinary trained team & standard guidelines for sepsis |

| Manaktala & Claypool (2017) | To evaluate the impact of a computerized surveillance algorithm & decision support system on sepsis mortality rates | Quasi-experimental | III | 58 patients in Huntsville hospital (tertiary care teaching hospital/ USA) | The system was sensitive & specific for sepsis identification & management & improved decision-making related to sepsis management. Mortality rate was reduced by 53% & readmission rate was reduced, with no effect on patient length of stay |

Weakness: Small sample size Strength: used different methods to detect mortality rate related to sepsis |

| Harley et al. (2019) | To explore and understand ER nurses’ knowledge of sepsis & identify gaps in clinical practice related to sepsis management. | Qualitative | VI | 14 ER nurses/ Australia | Nurses had poor knowledge, attitudes, & practices related to sepsis assessment & management. Barriers to sepsis management included high number & severity of sepsis conditions, nurses’ poor knowledge of sepsis, heavy workloads, & inexperienced ER doctors |

Weakness: fatigue was a threat to internal validity, single center, & use of self-report tools Strength: used detailed face to face interviews |

| Yousefi et al. (2012) | To review the effect of an educational program on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, & practices related to the identification & management of sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 64 ICU nurses/ Iran | Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, & practices were improved after the intervention |

Weakness: Differences in ICU facilities and equipment made it difficult to generalize the findings Strength: used of valid & reliable tool |

| Nucera et al. (2018) | To assess knowledge and attitudes related to sepsis among ICU and non-ICU nurses and physicians | Quasi- experimental | III | 11 different wards (ICU and non-ICU) in Italy | Nurses’ attitudes towards blood culture technique were poor & their knowledge of blood culture procedures & sepsis risks was good (>75%). Nurses had poor knowledge (<50%) of methods for the early identification, diagnosis, & management of sepsis. Their knowledge of sepsis improved after the intervention educational program |

Weakness: Heterogeneity of the sample Strength: High response rate and zero attrition rate |

| Rahman et al. (2019) | To explore nurses’ knowledge & attitudes related to the early identification & management of sepsis | Cross-sectional | VI | 120 ER in Malaysia | Nurses had poor knowledge of & neutral attitudes towards sepsis. |

Weakness: single center & low validity Strength: detailed description of instruments |

| Storozuk et al., (2019) | To assess ER nurses’ knowledge of sepsis & their perspectives towards caring for patients with sepsis | Cross-sectional | VI | 758 ER nurses/ Canada | Most nurses had poor knowledge of sepsis & SIRS definition, general knowledge, & treatment. Nurses were aware of the need to update their knowledge related to the early identification & timely management of sepsis to reduce complications |

Weakness: single site Strength: the questionnaire used was based on the standard guidelines of the SSC |

| Gyang et al. (2015) | To evaluate the use of NDS for early sepsis identification | Observational pilot | IV | 245 patients with sepsis in intermediate care settings/ USA | The NDS had 95% sensitivity and 92% specificity. | Strength: used a highly sensitive screening tool Weakness: one geographical site |

| El Khuri et al. (2019) | To assess the effect of EGDT in the ER on mortality rates related to sepsis and septic shock | Retrospective cohort | IV | 290 patients with sepsis from one large tertiary hospital in Lebanon | There were no differences between the two groups in time & duration of vasopressor, antibiotics, and length of stay. The implementation of EGDT in the ER decreased the mortality rate from 47.6% to 31.7%. The most common cause of infection leading to sepsis was LRTI. |

Strength: first study conducted in Lebanon Weakness: conducted in one site |

| Vanderzwan et al. (2020) | To apply a multimodel nursing pedagogy with medium fidelity simulation senarios for the early identification & management of sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | All critical care nurses in an academic medical center/ USA | Nurses’ knowledge & competency related to the early identification & management of sepsis improved after simulation |

Weakness: Only face validity was used to validate the questionnaire Strength: used multimodal in intervention |

| R. J. Roberts et al. (2017) | To evaluate nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, & perceptions related to antibiotic innitiation for patients with sepsis | Cross-sectional | VI | 122 critical care nurses/ USA | Nurses had good knowledge related to defining septic shock & were aware of Aware of when to administer antibiotics. Lack of awareness of the importance of antibiotics initiation, lack of IV access, & the need for multiple medications rather than antibiotics were major barriers to sepsis management |

Weakness: Self-selection and single center Strength: valid tools |

| McKinley et al. (2011) | To compare between paper protocols & computerized protocols for standarizing sepsis decision-making | Quasi- experimental | III | 948 ICU nurses in an academic tertiery hospital in the USA | The computerized protocol led to quicker antibiotic administration, blood culture collection, and lactate level checking as compared to the paper-based protocol. The computerize protocol had 97% sensitivity & 97% specificity to the standardized & rapid implementation of evidence-based treatment guidelines of sepsis |

Weakness: Technical issues in implementing the protocol Strength: the intervention was applied over a long period of time |

| Drahnak et al. (2016) | To assess the impact of an educational program on nurses’ knowledge, perceptions, & attitudes related to sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 680 ICU & ER nurses/ Pennsylvania, USA | Knowledge of sepsis was improved after the educational program. There was significant improvement in nurses’ ability to identify patients with sepsis |

Weakness: high attrition rates Strength: used standard guidelines for sepsis assessment |

| Proffitt and Hooper (2020) | To assess nurses’ perceptions towards the implementation of the 106 q-sofa assessment tool for sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 14 ER nurses/ USA | The use of this tool led nurses to become more autonomous in making decisions related to sepsis, thus leading to prompt management of sepsis. Nurses perceived the lack of time to be a barrier to the implementation of the evidence-based treatment guidelines |

Weakness: small sample size, single center Strength: employing a new sepsis screening tool |

| Rajan and Rodzevik (2021) | To explore the differences between ER nurses receiving an educational program on the early identification & management of sepsis & nurses not receiving the program | Quasi- experimental | III | 22 ER nurses/ USA | Using sepsis standing orders combined with the educational program contributed to the early identification of sepsis and better quality of care provided. |

Weakness: Small sample size & single center Strength: |

| Oliver (2018) | To assess the impact of EGDT on the early detection of sepsis in an ED | Quasi-experimental | III | 63 patients with sepsis /USA | Revealed no significant differences in lactate measurement and blood culture collection but a decrease in time until antibiotic administration |

Weakness: Single center, screening tool implemented over a short time period Strength: used valid and reliable tools |

| Burney et al. (2012) | To identify the barriers related to sepsis treatment | Descriptive-cross sectional | VI | 101 ER nurses/ USA | Shortage of nurses, unavailability of ICU beds and limited physical space in were the most reported barriers to sepsis treatment |

Weakness: single center and used self-report questionnaire Strength: provide detailed explanation about the barriers |

| Edwards & Jones (2021) | To examine nurses’ levels of knowledge, attitude, and skills related to sepsis management | Descriptive-cross sectional | VI | 98 acute medical-surgical nurses/ UK | Nurses incorrectly answered the questions related to knowledge of sepsis and demonstrated positive attitudes. |

Weakness: used self-report questionnaire Strength: used multi-settings |

| Steinmo el al. (2015) | To explore the effect of using behavioral science tools to modify the existing quality improvement guidelines for “Sepsis Six” implementation | Qualitative | VI | 19 ER nurses, 12 ER doctors, 2 midwives and 1 healthcare assistant/ UK | Using behavioral science tools was feasible to modify the existing quality improvement guidelines for “Sepsis Six” implementation. The tools are compatible with the currently used pragmatic approach. |

Weakness: fatigue was a threat to internal validity. Strength: used multi-settings and detailed face to face interviews |

| Giuliano et al. (2005) | to examine nurses’ understanding of clinical practice related to assessment of sepsis as well as their knowledge of diagnostic criteria for sepsis | Descriptive-cross sectional | VI | 517 nurses& 100 physicians/ USA | The majority of participants routinely use the findings of PAP, Bp, O2 Sat, and ECG to assess and manage sepsis |

Weakness: used self-report questionnaire Strength: large sample |

| Ferguson et al. (2019) | To assess the effectiveness of QI initiative in improving the early assessment and management of sepsis | Retrospective cohort | IV | 106,220 patients with sepsis from a medical center in Seatle/USA | The implementation of QI improved ER sepsis bundle adherence by 33.2%, decreased sepsis-related RRT calls by 1.35% & in-hospital sepsis-related mortality rate by 4.1% (p<0.001) |

Weakness: conducted in one site Strength: very large sample size |

| Giuliano et al. (2010) | To examine the difference in mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation between nurses exposed to 2 different monitor displays in response to simulated case scenarios of sepsis | Quasi-experimental | III | 75 critical care nurses/ USA | mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation were shorter nurses exposed to EBM. |

Weakness: screening tool implemented over a short time period & pilot study. Strength: used control group and random assignment |

| Kabil et al. (2021) | To explore ER nurses’ experiences of initiating early goal-directed fluid resuscitation in patients with sepsis | Qualitative | VI | 10 ER nurses/ Australia | participating nurses identified different factors limiting the prompt initiation of early goal-directed fluid resuscitation, some challenges to the clinical practice of sepsis, and solutions to these challenges. Most nurses suggested incorporating nurse-initiated early goal-directed fluid resuscitation for patients with sepsis. |

Weakness: limited generalizability of findings & interpretation bias Strength: used detailed face to face interviews |

USA: United States of America; UK; United Kingdom; ACS: acute care settings; ER: emergency room; ICU: intensive care units; SIRS: Systematic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; KAP: knowledge, attitudes, and practice; qSOFA: Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; EGDT; Early Goal-Directed Therapy; NDS: Nurse Driven Sepsis Screening tool; SIRS: Sepsis Inflammatory Response; MEW-S: Modified Early Warning Score; LRTI: Lower respiratory tract infection; IQ: Quality Improvement; EBM: Enhanced Bedside Monitor; RRT: rapid response team.

Ethical considerations

There was no need to obtain ethical approval to conduct this systematic review since no human subjects were involved.

Quality assessment and data synthesis

A quality assessment of the selected studies was performed independently by two researchers based on the guidelines of Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt [14]. Disagreements between the two researchers (MR, DB) were identified and resolved through a detailed discussion held during a face-to-face meeting. For complicated cases, the researchers (MR, DB) requested a second opinion from a third researcher (AH). According to the guidelines of Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt [14], twelve of the studies were at level 3 in terms of quality, four studies at level 5, and nine studies at level 6.

A qualitative synthesis was performed to synthesize the findings of the reviewed studies. The following steps were applied throughout the process of data synthesis:

The data in the selected studies were assessed, evaluated, contrasted, compared, and summarized in a table (Table 2). This data included the design, purpose, sample, main findings, strengths/limitations, and level of evidence for each of the studies.

The similarities and differences between the main findings of the selected studies were highlighted.

The strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies were discussed.

Results

Description of the selected studies

Most of the reviewed studies were conducted in Western countries [9, 11, 12], with only one study conducted in Eastern countries [1], and two in Middle-Eastern countries [15, 16]. The detailed geographical distribution of the studies and other characteristics are described in Table 2.

Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices

Nine of the selected studies assessed nurses’ knowledge and attitudes related to sepsis assessment and management in critically ill adult patients [1, 9, 12, 15, 17–21] (Table 3). Nucera et al. [18] found that ICU nurses had poor attitudes towards blood culture collection techniques and timing and poor levels of knowledge related to the early identification, diagnosis, and management of sepsis. For example, the majority of nurses reported that there is no need to sterilize the tops of culture bottles, and there is no specific time for specimen collection [18]. However, the participating nurses reported good levels of knowledge related to blood culture procedures and the risk factors for sepsis. Similarly, R. J. Roberts et al. [19] found the participating nurses to have good knowledge of septic shock and good attitudes toward the initiation of antibiotics for critically ill adult patients with sepsis. Only two studies assessed nurses’ practices related to sepsis assessment and management [15, 19]. For example, in the study of R. J. Roberts et al. [19], 40% of the nurse participants reported that they were aware of the importance of initiating antibiotics and IV fluid within one hour of septic shock recognition [20]. Also, Yousefi et al. [15] found the participating nurses to have good practices related to sepsis assessment and management.

Table 3. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management.

| Study | Knowledge (Mean Score, interpretation) | Attitudes (Mean Score, interpretation) | Practices (Mean Score, interpretation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van den Hengel et al. (2016) | 15.9±3.21, above average | N/A | N/A |

| Rahman et al. (2018) | MNR, Moderate | *21–27, neutral | N/A |

| Storozuk et al. (2019) | ¥51.8%, Poor | N/A | N/A |

| Harley et al. (2019) | MNR, Poor | N/A | N/A |

| Nucera et al. (2018) | MNR, Good | *51–75, poor | N/A |

| R.J. Roberts et al. (2017) | MNR, Good | N/A, positive | MNR, good |

| Yousefi et al. (2012) | 64.5±5.21, MNR | 73±4.51, MNR | 81±4.31, MNR |

| Edwards & Jones (2021) | 40.8%, Poor | 25±2.97, positive | N/A |

| Giuliano et al. (2005) | MNR | N/A | N/A |

*A range of the score reported

¥ a percentage of correct answers reported; MNR: Measured but not reported; N/A: Not Applicable

Barriers to and facilitators of sepsis assessment and management

The reviewed studies identified three types of barriers to the early identification and management of sepsis, namely patient-, nurse-, and system-related barriers (Table 4). Meanwhile, only nurse- and system-related facilitators were reported in the reviewed studies. The most-reported barriers and facilitators were system-related. The reported barriers included (a) the lack of written sepsis treatment protocols or guidelines adopted as hospital policy [22, 23]; (b) the complexity and atypical presentation of the early symptoms of sepsis [19]; (c) nurses’ poor level of education and clinical experience [1, 12]; (d) the lack of sepsis educational programs or training workshops for nurses [22, 23]; (e) the high comorbid burden among patients with sepsis, which complicates the critical thinking process of sepsis management [19]; (f) nurses’ deficits in knowledge related to sepsis treatment protocols and guidelines [22–24]; (g) the lack of mentorship programs in which junior nurses’ actions/activities are strictly supervised by experienced nurses [17, 23]; (h) heavy workloads or high patient-nurse ratios [22]; (i) the shortage of well-trained and experienced physicians, particularly in EDs [19, 22, 23]; (j) the lack of awareness related to antibiotic use for patients with sepsis [19, 22]; (k) the lack of IV access and unavailability of ICU beds [25]; (l) the non-use of drug combinations for the treatment of sepsis [22, 26, 27], and (m) poor teamwork and communication skills among healthcare professionals [22, 26]. Only three facilitators of sepsis assessment and management were identified in the reviewed studies. These facilitators were (1) nurses’ improved confidence in caring for patients with sepsis, (2) increased consistency in sepsis treatment, and (3) positive enforcement of successful stories of sepsis management [22, 27].

Table 4. The barriers to and facilitators of sepsis assessment and management.

| Barriers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Patient-related barriers | Nurse-related barriers | System-related barriers |

| • Complexity and atypical presentation of the early symptoms of sepsis • High comorbid burden among patients with sepsis, which complicates the critical thinking of sepsis management |

• Nurses’ poor level of education and clinical experience • Nurses’ knowledge deficits regarding the protocols and guidelines for the treatment of sepsis • Lack of awareness related to antibiotic use for patients with sepsis • Poor teamwork and communication skills among healthcare professionals |

• Lack of written sepsis treatment protocols or guidelines adopted as hospital policies • Lack of sepsis educational programs or training workshops for nurses • Lack of mentorship programs in which junior nurses’ actions/activities are strictly supervised by experienced nurses • Heavy workloads or high patient-nurse ratios • Shortage of well-trained and experienced physicians, particularly in EDs • Lack of IV access and unavailability of ICU beds • Non-use of drug combinations for sepsis treatment |

| Facilitators | ||

| Nurse-related | System-related | |

| • Nurses’ improved confidence in caring for patients with sepsis | • Enhanced consistency in sepsis treatment • Positive enforcement of successful stories of sepsis management |

|

Measurement tools of sepsis-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices

One of the reviewed studies used a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice (KAP) questionnaire developed according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines [15] to measure nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management. Meanwhile, eight studies [1, 9, 12, 17–21] used self-developed questionnaires based on the literature and SSC guidelines and validated by expert panels. Details of these measurement tools and their psychometric properties are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5. A summary of the measurement tools and their psychometric properties.

| Study | Name of the tool | Measured variable(s) | Description of the tool | # of items | Total score | Validity | Reliability* | Piloted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van den Hengel et al. (2016) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge of sepsis and SIRS criteria | General information about sepsis, SIRS, protocol, treatments, & case studies | 35 | 29 | Validated by expert panel | 0.53 | No |

| Oliver (2018) | Self-developed questionnaire | knowledge & practices related to antibiotic administration for sepsis | Information about sepsis management protocol & barriers to rapid antibiotic administration | NR | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Rahman et al. (2019) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge & attitudes towards sepsis | Questions on the indicators of SIRS, sepsis criteria, case scenarios, and attitudes towards the early identification and management of sepsis | 39 | 39 | Face & content validity were assessed | 0.86 | Yes |

| Storozuk et al. (2019) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge of sepsis | Questions about the signs & symptoms of sepsis, sepsis criteria, definition of sepsis, at- risk patients, & treatment | 225 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Harley et al. (2019) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge of sepsis | Questions on sepsis, sepsis criteria, SIRS, q SOFA, nursing role, & barriers to the early identification of sepsis | 22 | NR | Qualitative content analysis | N/A | No |

| Nucera et al. (2018) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge & attitudes towards sepsis | Questions on the riskiest sepsis procedures, knowledge about the early identification of sepsis, & attitudes towards blood culture collection techniques | 26 | NR | NR | 0.88 | Yes |

| Edwards & Jones (2021) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge, skills & attitudes towards sepsis | Closed & open-ended questions on nurses’ opinions and experiences regarding sepsis | 24 | NR | NR | NR | Yes |

| Yousefi et al. (2012) | KAP | Knowledge, attitudes, & practices related to sepsis | Questions about knowledge, attitudes, & practices related to sepsis | 46 | NR | Content validity was assessed | 77–90.7 | No |

| Giuliano et al. (2005) | Self-developed questionnaire | Knowledge of diagnostics criteria for sepsis | Questions about the physiologic parameters routinely used to assess for sepsis | 20 | NR | NR | Not measured | No |

SIRS: Systematic Inflammatory Response Syndrome; KAP: knowledge, attitudes, and practice; NR: not reported; qSOFA: Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

* Cronbach’s Alpha

Interventions directed at improving nurses’ sepsis assessment and management

Educational programs

Only four of the selected studies examined the impact of educational programs on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis management and found significant improvements in nurses’ posttest scores (Table 6) [11, 15, 28, 29]. For example, Drahnak’s study [28] implemented an educational program developed by the authors and integrated with patients’ health electronic records (HER) and found significant improvements in nurses’ post-test nursing knowledge scores. Another educational program developed by the authors was implemented to improve ICU nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis and found a significant improvement in posttest scores among the intervention group [15]. Another study was designed to examine the effectiveness of the Taming Sepsis Educational Program® (TSEP™) in improving nurses’ knowledge of sepsis [11]. A 15-minute structured educational session was developed to decrease the mean time needed to order a sepsis order set for critically ill patients through improving ER nurses’ knowledge about SSC guidelines and found that the mean time was reduced by 33 minutes among the intervention group [29].

Table 6. Sepsis education programs and simulations.

| Study | Intervention/Control | Assessment Times | Measured Variable(s) | Differences in Posttest Scores Between Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delaney et al. (2015) | *I: received 2 educational sessions. The first session consisted of 4 hours of online learning. The second session consisted of active participation in videotapes, high fidelity simulation, case scenarios, and debriefing sessions focusing on early sepsis assessment, care of septic patients, IHI bundles stages of sepsis, case studies, HLCC, & bundles of sepsis. | Post intervention |

Nurses’ knowledge on: IHI bundles, SST, STEPS communication, & HLCC Nurses’ competency: Sepsis assessment Sepsis management EGDT initiation |

+0.22 +0.32 +0.16 +0.02 +21.45 +24.16 +19.25 |

| Yousefi et al. (2012) | I: received one PPT session (8 hour) about sepsis care, treatment, prevention, principles, nosocomial infections, and guidelines integrated with pamphlets. Assessed nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices three times (pre-intervention, immediately post intervention, and three weeks post intervention). C: did not receive an educational program |

Pre-intervention, immediately post intervention, & three weeks post intervention. |

Immediately Posttest Knowledge: Attitudes: Practices: 3 weeks post intervention: Knowledge Attitudes Practices |

+21.0 +6.4 +7.6 +21.7 +10.1 +8.6 |

| Drahnak (2016) | *I: received one session (30 minutes) with a voice-over slide presentation & role-play case study focusing on the pathophysiology of sepsis, risk factors for sepsis, SSC guidelines, case studies, and assessment of sepsis, integrated with HER | Before the educational program 1 month post intervention |

Knowledge Attitudes Screening adherence: *Non-adherence *Partial adherence *Adherence |

+56.22 -18.25 -31.74 +28.5 +3.4 |

| Rajan et al. (2021) | I: received a structured educational session (15 minutes) focused on SIRS criteria, sepsis criteria, policy, sepsis screening tools, and sepsis standing order. C: did not receive an educational session |

Post intervention | Time for sepsis identification | -33 minutes |

| Vanderzwan et al. (2020) | *I: received medium fidility simulation for 15 minutes. Nurses also received educational session about CLMS. | LMS & one week post simulation | Knowledge retention & competency related to the early identification & management of sepsis |

outcomes improved after simulation |

| Giuliano et al. (2010) | I: exposed to EBM display which is a continuous visual display of combinations of recent data trends & parameters to promote early recognition of sepsis in response to a computer-simulated scenarioC: exposed to SBM display of 5 parameters including BP, ECG, PAP, CO, and O2 Sat which need to be intereprted by clinicans to meaningful data in response to a computer-simulated scenario • All partciapnts received educational program on sepsis assessment and management based on SSC guidelines | Immediately Pre-intervention & post intervention | Response time to the different monitor displays Time for sepsis recognition Times for SSC-recommended interventions initiation |

Similar responses -1.32 minutes -1.33 minutes |

*one group only; MNR: Measured but not reported, IHI bundles: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; HLCC; Health literacy and culture competency; EGDT; Early Goal Directed Therapy; SST: Staging sepsis Team; CLM: computerized Learning Management Systems; HER: Electronic Health Record; I: Intervention; C: Control; EBM: Enhanced Bedside Monitor; SBM: Standard Bedside Monitor; CDSS: Clinical Decision Support System

Simulation

Only two studies examined the effect of using simulation in improving the early recognition and prompt treatment of sepsis by critical care nurses (Table 6) [30, 31]. Vanderzwan et al. [30] assessed the effect of a medium-fidelity simulation incorporated into a multimodel nursing pedagogy on nurses’ knowledge of sepsis and showed significant improvements in six of the nine questionnaire items. While Giuliano et al. examined the difference in mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation between nurses exposed to two different monitor displays in response to simulated case scenarios of sepsis and showed a significant reduction in the mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation by those nurses who were exposed to enhanced bedside monitor (EBM) display [31].

Decision support tools

Four of the selected studies examined the effectiveness of decision support tools, adapted based on the SSC guidelines and the “sepsis alert protocol”, on the early identification and management of sepsis and confirmed the effectiveness of these tools (Table 7) [32–35]. The decision support tools used in three of the studies guided the nurses throughout their decision-making processes to reach effective assessment, high quality and timely management of sepsis, and, in turn, optimal patient outcomes [32, 33, 35]. However, no significant differences in the time of blood culture collection and antibiotic administration were reported between the intervention and control groups in the study of Delawder et al. [34].

Table 7. Sepsis decision-making support and screening tools and treatment protocols.

| Study | Decision tool/sepsis protocol or tool | Description of the tool or protocol | Main effects on patient outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manaktala et al. (2017) | Sepsis Survilence Algorithim | The screening tool assesses sepsis clinical parameters (physical exam & lab test) & sends alam signals to nurses about positive findings. | Sepsis mortality rate was reduced by 53% & 30 day readmission was reduced from 19.08% to 13.21%. The tool sensitivity & specificity were 95% and 82%, respectively. |

| Amland et al. (2015) | Sepsis alert (Binary alarm system) | The tool consists of two steps. The first step is the detection of actual or potential sepsis, and the second is screening & stratification conducted within 15 minutes | 89% of septic patients were detected by the alert system, & screening and stratification was completed for 75% of the cases within an hour from notification. The tool sensitivity was 94%. |

| Long et al. (2018) | User interface alert | User interface alert was designed for medical systems to a provide computer support system for decision-making related to sepsis | The tool enhanced reliability & specificty of patient data for detecting sepsis & provided an effective clinical decision support system for nurses to innititate sepsis assessment & management |

| Delawder et al. (2019) | Sepsis alert algorithim | Sepsis alert algorithim was designed to initiate full screening of sepsis when the nurse receives an electronic notification. This alert depends on the SIRS criteria & SSC guidelines | The alert algorithm can improve the time taken to implement sepsis guidelines except for antibiotics administration & blood culture collection. Mortality rate was decreased from 12.45% to 4.55%. |

| Proffitt et al. (2020) | qSOFA | It includes 2 parts, the first part being the assessment of potential infection & the second part being the assessment of Q-SOFA score, which is calculated based on GCS, systolic BP & RR. | The use of qSOFA led nurses to become more autonomous in making decisions related to sepsis management. The median time from ER admission to triage evaluation was reduced by 9 minutes. |

| McKinley et al. (2011) | TMH | If the patient had MAP<65 mmHg, LL >4 mmol/L, or U.O <0.5 mg/kg/hr, diagnostic tests, broad spectrum antibiotics, & fluid were initiated, and the lactate test was repeated after 4 hours. If the patient met two or more of the previous criteria, central venous line application would be added to the management plan | Time taken to initiate antibiotic administration, blood culture collection, & lactate level assessment & nurses’ compliance to sepsis treatment guidelines were improved, and the mortality rate declined with the use of TMH. The sensitivity & specificity of the TMH were 97%. |

| Oliver et al. (2018) | EGDT & NDS | The protocols are based on the SSC guidelines, and focus on blood culture, lactate measurement, and antibiotic administration | No significant differences in lactate measurement & blood culture collection were identified, but the time taken for antibiotic administration was improved. |

| Roney et al. (2020) | MEW-S | This tool was used for the early identification of at-risk patients based on the early signs of status deterioration according to body temperature, BP, RR, LOC, WBC, U.O & L.L. | MEW-S facilitated the early identification of sepsis & provision of timely management. The mortality rate declined by 24%. |

| Jacobs et al. (2020) | NDS | This tool was developed based on the SSC guidelines & had 4 steps: (1) measure lactate level, (2) take blood culture, (3) provide broad spectrum antibiotics, (4) administer 30 ml/kg crystalloid fluid if hypotensive & LL > 4 mmol/L, & (5) measure bilirubin, creatinine, GCS, MAP, RR, PT, PTT & platelets account. | The readmission rate was reduced from 36.28% to 25% 8 weeks after the NDS protocol, and compliance to the sepsis intervention protocol improved but with no effect on mortality rate. |

| Gyang et al. (2015) | NDS | Developed based on the SSC guidelines: (1) if the patient met >2 of the SIRS criteria>>> suspected sepsis; (2) if the patient screened >2 SIRS criteria >>> confirmed sepsis and presence of infection; (3) document findings in EHR & call physician | The tool sensitivity and specificity were 95.5% and 91.9%, respectively. |

| El-khuri et al. (2019) | EGDT | Developed based on the SSC guidelines depending on the following measurements: SIRS criteria, vital signs, U.O, O2 level, cardiac index, & continuous monitoring | There were no differences between the two groups in time and duration of vasopressor, antibiotic administration, or length of stay. However, the mortality rate was decreased from 47.6% to 31.7% with the implementation of EGDT. |

| Ferguson et al. (2019) | QI | Developed based on the SSC guidelines with few modifications: (1) administer 2 L of fluid instead of 30 ml/kg (2) apply it on patients with suspected infection, and (3) with 2 or more SIRS criteria | ER sepsis bundle adherence was improved by 33.2%, sepsis-related RRT calls was decreased by 1.35% & in-hospital sepsis-related mortality rate by was decreased 4.1% (p<0.001) |

qSOFA: Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; TMH: The Methodist Hospital; NDS: Nurse Driven Sepsis Screening tool; EGDT: Early Goal-Directed Therapy; SSC: Surviving Sepsis Campaign; SIRS: Sepsis Inflammatory Response; HER: Electronic Health Records; UO: Urine Output; O2: oxygen; Map: Mean Arterial Pressure; GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; RR: Respiratory Rate; PT: Prothrombin Time; PTT: Partial Thromboplastin Time; LL: Lactate level; QI: Quality Improvement; RRT: rapid response team.

Sepsis protocols

Eight of the selected studies examined the effectiveness of sepsis protocols [24, 36–38] and sepsis screening tools [16, 39–41] for the early assessment and management of sepsis (Table 7). All of these articles revealed that the implementation of sepsis screening tools or protocols based on the SSC guidelines leads to the early identification and timely management of sepsis, as well as the improvement in nurses’ compliance to the SSC guidelines for the detection and management of sepsis. For example, in one study, patients who received Early Goal-Directed Therapy (EGDT) had a lower mortality rate as compared to patients who received usual care [16]. The sepsis screening tools and guidelines were also tested to examine their impact on some patient outcomes, and variabilities were identified. For example, the use of the Modified Early Warning Score (MEW-S) tool revealed no significant improvement in patient mortality rate [41]. In contrast, mortality rates were decreased by using the Nurse Driven Sepsis Protocol (NDS) [40], Quality Improvement (QI) initiative [38], and a computerized protocol [37]. In addition, nurses in the computerized protocol group had better compliance with the SSC guidelines than did nurses in the paper-based group [37]. One of the selected studies compared between a paper-based sepsis protocol and a computer-based protocol and found that antibiotic administration, blood cultures, and lactate level checks were conducted more often and sooner by nurses in the computerized protocol group [37]. Two of the selected studies used the EGDT as a screening tool for sepsis and found no significant differences in times of diagnosis, blood culture collection, or lactate measurements between the control and intervention groups [16, 24]. However, significant differences were found in the time of antibiotic administration in the study of Oliver et al. [24]. Although El-khuri et al. [16] revealed no significant differences in the time of antibiotic administration, the mortality rate among patients in the intervention group declined significantly.

Discussion

Most of the reviewed studies focused on assessing critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management, revealing poor levels of knowledge, moderate attitude levels, and good practices. Also, this review revealed that the three most common barriers to effective sepsis assessment and management were nursing staff shortages, delayed initiation of antibiotics, and poor teamwork skills. Meanwhile, the three most common facilitators of sepsis assessment and management were the presence of standard sepsis management protocols, professional training and staff development, and positive enforcement of successful stories of sepsis treatment. Moreover, this review reported on a wide variety of interventions directed at improving sepsis management among nurses, including educational sessions, simulations, screening or decision support tools, and intervention protocols. The impacts of these interventions on patient outcomes were also explored.

The findings of our review are consistent with the findings of previous studies which have explored critical care nurses’ knowledge related to sepsis assessment and management [42]. Also, recent studies conducted in different clinical settings support the findings of our review regarding nurses’ knowledge of sepsis. For example, a recent study conducted in a medical-surgical unit revealed that nurses had good knowledge of early sepsis identification in non-ICU adult patients [43]. The variations in nurses’ levels of knowledge related to sepsis assessment were attributed to variations in educational level and work environment (i.e., ICU vs. non-ICU).

The evidence indicates that the successful treatment of critically ill patients with suspected or actual sepsis requires early identification or assessment [44, 45]. Early assessment is a critical step for the initiation of antibiotics for patients with sepsis, leading to improved patient outcomes and a decline in mortality rates [44]. The current review also revealed the significant role of educational programs in improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early recognition and management of sepsis. These findings are in line with the findings of another study, which tested the impact of e-learning educational modules on pediatric nurses’ retention of knowledge about sepsis [45]. The study revealed that the educational modules improved the nurses’ knowledge acquisition and retention and clinical performance related to sepsis management [45]. The findings of our review related to sepsis screening and decision support tools are in congruence with the findings of a previous clinical trial which assessed the impact of a prompt telephone call from a microbiologist upon a positive blood culture test on sepsis management [46]. The study revealed that this screening tool contributed to the prompt diagnosis of sepsis and antibiotic administration, improved patient outcomes, and reduced healthcare costs [46]. The findings of our review related to the effectiveness of educational programs in improving the assessment and management of sepsis were consistent with the findings of a recent quasi-experimental study. The study found that incorporating sepsis-related case scenarios in ongoing educational and professional training programs improved nurses’ self-efficacy and led to a prompt and accurate assessment of sepsis [47]. One of the interventions explored in this review was a simulation that facilitated decision-making related to sepsis management. The simulation was found to be effective in mimicking the real stories of patients with sepsis and proved to be a safe learning environment for inexperienced nurses before encountering real patients, increasing nurses’ competency, self-confidence, and critical thinking skills [48]. Also, a recent study showed that the combination of different interventions aimed at targeting sepsis assessment and management, including educational programs and simulation, may lead to optimal nurse and patient outcomes [49].

Limitations

The present review has several limitations. There is limited variability in the findings of the reviewed studies in terms of the main variable, sepsis. Moreover, the review excluded studies written in languages other than English and conducted among populations other than critical care nurses. However, there may be studies written in other languages which may have significant findings not considered in this review. Further, only eight databases were used to search for articles related to the topic of interest, which may have limited the number of retrieved studies. Finally, due to the heterogeneity between the selected studies, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Relevance to clinical practice

Our findings could help hospital managers in developing continuous education and staff development training programs on assessing and managing sepsis for critical care patients. Establishing continuous education, workshops, professional developmental lectures focusing on sepsis assessment and management for critical care nurses, as well as training courses on how to use evidence-based sepsis protocol and decision support and screening tools for sepsis, especially for critical care patients are highly recommended. Also, our findings could be used to development of an evidence-based standard sepsis management protocol tailored to the unmet healthcare need of patients with sepsis.

Conclusion

To date, nurses remain to have poor to good knowledge of and attitudes towards sepsis and report many barriers related to the early recognition and management of sepsis in adult critically ill patients. The most-reported barriers were system-related, pertaining to the implementation of evidence-based sepsis treatment protocols or guidelines. Our review indicated that despite all educational interventions, no study has collectively targeted nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the assessment and treatment of sepsis using a multicomponent interactive teaching method. Such a method would aim to guide nurses’ decision-making and critical thinking step by step until a prompt and effective treatment of sepsis is delivered. Also, despite all available protocols and guidelines, no study has used a multicomponent intervention to improve health outcomes in adult critically ill patients. Future research should focus on sepsis-related nurse and patient outcomes using a multilevel approach, which may include the provision of ongoing education and professional training for nurses and the implementation of a multidisciplinary sepsis treatment protocol.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Liberian of Jordan University of Science and Technology for his help in conducting this review.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the article and its files.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by The deanship of research at Jordan University of Science and Technology (grant number 20200668).

References

- 1.Rahman NI, Chan CM, Zakaria MI, Jaafar MJ. Knowledge and attitude towards identification of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and sepsis among emergency personnel in tertiary teaching hospital. Australasian emergency care. 2019. Mar 1;22(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Mellhammar L, Rose N, Cassini A, Rudd KE, Schlattmann P, et al. Incidence and mortality of hospital-and ICU-treated sepsis: results from an updated and expanded systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive care medicine. 2020. Aug;46(8):1552–62. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06151-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama. 2016. Feb 23;315(8):801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skube SJ, Katz SA, Chipman JG, Tignanelli CJ. Acute kidney injury and sepsis. Surgical infections. 2018;19(2):216–24. doi: 10.1089/sur.2017.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillen-Guio B, Lorenzo-Salazar JM, Ma SF, Hou PC, Hernandez-Beeftink T, Corrales A, et al. Sepsis-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome in individuals of European ancestry: a genome-wide association study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2020. Mar 1;8(3):258–66. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30368-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiaschi-Taesch NM, Kleinberger JW, Salim FG, Troxell R, Wills R, Tanwir M, et al. Human pancreatic β-cell G1/S molecule cell cycle atlas. Diabetes. 2013. Jul 1;62(7):2450–9. doi: 10.2337/db12-0777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iba T, Umemura Y, Watanabe E, Wada T, Hayashida K, Kushimoto S, et al. Diagnosis of sepsis‐induced disseminated intravascular coagulation and coagulopathy. Acute Medicine & Surgery. 2019. Jul;6(3):223–32. doi: 10.1002/ams2.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leviner S. Post–Sepsis Syndrome. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2021. Apr 1;44(2):182–6. doi: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van den Hengel LC, Visseren T, Meima-Cramer PE, Rood PP, Schuit SC. Knowledge about systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis: a survey among Dutch emergency department nurses. International journal of emergency medicine. 2016. Dec;9(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowan S, Holland J, Kane A, Frost I. What are the barriers to improving care for patients with sepsis?. Clinical Medicine. 2015. Jun 1;15(Suppl 3):s24–s24. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-3-s24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delaney MM, Friedman MI, Dolansky MA, Fitzpatrick JJ. Impact of a sepsis educational program on nurse competence. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. 2015. Apr 1;46(4):179–86. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20150320-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storozuk SA, MacLeod ML, Freeman S, Banner D. A survey of sepsis knowledge among Canadian emergency department registered nurses. Australasian emergency care. 2019. Jun 1;22(2):119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2019.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meade C. Intensive Care Unit Nurse Education to Reduce Sepsis Mortality Rates. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, editors. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yousefi H, Nahidian M, Sabouhi F. Reviewing the effects of an educational program about sepsis care on knowledge, attitude, and practice of nurses in intensive care units. Iranian journal of nursing and midwifery research. 2012. Feb;17(2 Suppl1):S91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Khuri C, Abou Dagher G, Chami A, Bou Chebl R, Amoun T, Bachir R, et al. The impact of EGDT on sepsis mortality in a single tertiary care center in Lebanon. Emergency medicine international. 2019. Jan 15;2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harley A, Johnston AN, Denny KJ, Keijzers G, Crilly J, Massey D. Emergency nurses’ knowledge and understanding of their role in recognising and responding to patients with sepsis: A qualitative study. International emergency nursing. 2019. Mar 1;43:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2019.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nucera G, Esposito A, Tagliani N, Baticos CJ, Marino P. Physicians’ and nurses’ knowledge and attitudes in management of sepsis: An Italian study. J Health Soc Sci. 2018;3(1):13–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts RJ, Alhammad AM, Crossley L, Anketell E, Wood L, Schumaker G, et al. A survey of critical care nurses’ practices and perceptions surrounding early intravenous antibiotic initiation during septic shock. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2017. Aug 1;41:90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards E, Jones L. Sepsis knowledge, skills and attitudes among ward-based nurses. British Journal of Nursing. 2021. Aug 12;30(15):920–7. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.15.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giuliano KK, Kleinpell R. The use of common continuous monitoring parameters: a quality indicator for critically ill patients with sepsis. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2005. Apr;16(2):140–8. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200504000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts N, Hooper G, Lorencatto F, Storr W, Spivey M. Barriers and facilitators towards implementing the Sepsis Six care bundle (BLISS-1): a mixed methods investigation using the theoretical domains framework. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2017. Dec;25(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breen SJ, Rees S. Barriers to implementing the Sepsis Six guidelines in an acute hospital setting. British Journal of Nursing. 2018. May 10;27(9):473–8. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2018.27.9.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver ND. Early Recognition of Sepsis in the Emergency Department. ARC Journal of Nursing and Healthcare. 2018;4(1):3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burney M, Underwood J, McEvoy S, Nelson G, Dzierba A, Kauari V, et al. Early detection and treatment of severe sepsis in the emergency department: identifying barriers to implementation of a protocol-based approach. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2012. Nov 1;38(6):512–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2011.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabil G, Hatcher D, Alexandrou E, McNally S. Emergency nurses’ experiences of the implementation of early goal directed fluid resuscitation therapy in the management of sepsis: a qualitative study. Australasian Emergency Care. 2021. Mar 1;24(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2020.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinmo SH, Michie S, Fuller C, Stanley S, Stapleton C, Stone SP. Bridging the gap between pragmatic intervention design and theory: using behavioural science tools to modify an existing quality improvement programme to implement “Sepsis Six”. Implementation science. 2015. Dec;11(1):1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drahnak DM, Hravnak M, Ren D, Haines AJ, Tuite P. Scripting nurse communication to improve sepsis care. MedSurg Nursing. 2016. Jul 1;25(4):233. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajan JJ, Rodzevik T. Sepsis Awareness to Enhance Early Identification of Sepsis in Emergency Departments. The journal of continuing education in nursing. 2021. Jan 1;52(1):39–42. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20201215-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vanderzwan KJ, Schwind J, Obrecht J, O’Rourke J, Johnson AH. Using simulation to evaluate nurse competencies. Journal for Nurses in Professional Development. 2020. May 1;36(3):163–6. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuliano KK, Johannessen A, Hernandez C. Simulation evaluation of an enhanced bedside monitor display for patients with sepsis. AACN Advanced Critical Care. 2010. Jan;21(1):24–33. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181bc8683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amland RC, Lyons JJ, Greene TL, Haley JM. A two-stage clinical decision support system for early recognition and stratification of patients with sepsis: an observational cohort study. JRSM open. 2015. Sep 24;6(10):2054270415609004. doi: 10.1177/2054270415609004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long D, Capan M, Mascioli S, Weldon D, Arnold R, Miller K. Evaluation of user-interface alert displays for clinical decision support systems for sepsis. Critical care nurse. 2018. Aug;38(4):46–54. doi: 10.4037/ccn2018352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delawder JM, Hulton L. An interdisciplinary code sepsis team to improve sepsis-bundle compliance: a quality improvement project. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2020. Jan 1;46(1):91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2019.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manaktala S, Claypool SR. Evaluating the impact of a computerized surveillance algorithm and decision support system on sepsis mortality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2017. Jan 1;24(1):88–95. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs JL. Implementation of an evidence-based, nurse-driven sepsis protocol to reduce acute care transfer readmissions in the inpatient rehabilitation facility setting. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal. 2020. Mar 1;45(2):57–70. doi: 10.1097/rnj.0000000000000205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKinley BA, Moore LJ, Sucher JF, Todd SR, Turner KL, Valdivia A, et al. Computer protocol facilitates evidence-based care of sepsis in the surgical intensive care unit. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2011. May 1;70(5):1153–67. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31821598e9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson A, Coates DE, Osborn S, Blackmore CC, Williams B. Early, nurse-directed sepsis care. AJN The American Journal of Nursing. 2019. Jan 1;119(1):52–8. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000552614.89028.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proffitt RD, Hooper G. Evaluation of the (qSOFA) tool in the emergency department setting: nurse perception and the impact on patient care. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 2020. Jan 1;42(1):54–62. doi: 10.1097/TME.0000000000000281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gyang E, Shieh L, Forsey L, Maggio P. A nurse‐driven screening tool for the early identification of sepsis in an intermediate care unit setting. Journal of hospital medicine. 2015. Feb;10(2):97–103. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roney JK, Whitley BE, Long JD. Implementation of a MEWS‐Sepsis screening tool: Transformational outcomes of a nurse‐led evidence‐based practice project. InNursing forum 2020. Apr (Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 144–148). doi: 10.1111/nuf.12408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boettiger M, Tyer-Viola L, Hagan J. Nurses’ early recognition of neonatal sepsis. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2017. Nov 1;46(6):834–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raines K, Berrios RA, Guttendorf J. Sepsis education initiative targeting qSOFA screening for non-ICU patients to improve sepsis recognition and time to treatment. Journal of nursing care quality. 2019. Oct 1;34(4):318–24. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Funk D, Sebat F, Kumar A. A systems approach to the early recognition and rapid administration of best practice therapy in sepsis and septic shock. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2009. Aug 1;15(4):301–7. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32832e3825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woods JM, Scott HF, Mullan PC, Badolato G, Sestokas J, Sarnacki R, et al. Using an elearning module to facilitate sepsis knowledge acquisition across multiple institutions and learner disciplines. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2021. Dec 1;37(12):e1070–4. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bunsow E, González-Del Vecchio M, Sanchez C, Muñoz P, Burillo A, Bouza E. Improved sepsis alert with a telephone call from the clinical microbiology laboratory: a clinical trial. Medicine. 2015. Sep;94(39). doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim B, Jeong Y. Effects of a case-based sepsis education program for general ward nurses on knowledge, accuracy of sepsis assessment, and self-efficacy. Journal of Korean Biological Nursing Science. 2020;22(4):260–70. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis AH, Hayes SP. Simulation to manage the septic patient in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Nursing Clinics. 2018. Sep 1;30(3):363–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herron JB, Harbit A, Dunbar JA. Subduing the killer-sepsis; through simulation. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine. 2018. Jul 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the article and its files.